Government having determined to make an

attempt to drive the French out of Egypt, despatched orders to the commander-in-chief to

proceed to Malta, where, on their arrival, the troops were informed of their destination.

Tired of confinement on board the transports, they were all greatly elevated on receiving

this intelligence, and looked forward to a contest on the plains of Egypt with the

hitherto victorious legions of France, with the feelings of men anxious to support the

honour of their country. The whole of the British land forces amounted to 13,234 men and

630 artillery, but the efficient force was only 12,334. The French force amounted to

32,000 men, besides several thousand native auxiliaries.

The fleet sailed in two divisions for

Marmorice, a bay on the coast of Greece, on the 20th and 21st of December, in the year

1800, The Turks were to have a reinforcement of men and horses at that place. The first

division arrived on the 28th of December, and the second on the 1st of January following.

Having received the Turkish supplies, which were in every respect deficient, the fleet

again got under weigh on the 23d of February, and on the morning of Sunday the 1st of

March the low and sandy coast of Egypt was descried. The fleet came to anchor in the

evening of 1st March 1801 in Aboukir bay, on the spot where the battle of the Nile had

been fought nearly three years before. After the fleet had anchored, a violent gale sprung

up, which continued without intermission till the evening of the 7th, when it moderated.

As a disembarkation could not be attempted

during the continuance of the gale, the French had ample time to prepare themselves, and

to throw every obstacle which they could devise in the way of a landing. No situation

could be more embarrassing than that of Sir Ralph Abercromby on the present occasion; but

his strength of mind carried him through every difficulty. He had to force a landing in an

unknown country, in the face of an enemy more than double his numbers, and nearly three

times as numerous as they were previously believed to be—an enemy, moreover, in full

possession of the country, occupying all its fortified positions, having a numerous and

well-appointed cavalry, inured to the climate, and a powerful artillery,—an enemy who

knew every point where a landing could, with any prospect of success, be attempted, and

who had taken advantage of the unavoidable delay, already mentioned, to erect batteries

and bring guns and ammunition to the point where they expected the attempt would be made.

In short, the general had to encounter embarrassments and bear up under difficulties which

would have paralysed the mind of a man less firm and less confident of the devotion and

bravery of his troops. These disadvantages, however, served only to strengthen his

resolution. He knew that his army was determined to conquer, or to perish with him; and,

aware of the high hopes which the country had placed in both, he resolved to proceed in

the face of obstacles which some would have deemed insurmountable.

The first division destined to effect a

landing consisted of the flank companies of the 40th, and Welsh Fusileers on the right,

the 28th, 42d, and 58th, in the centre, the brigade of Guards, Corsican Rangers, and a

part of the 1st brigade, consisting of the Royals and 54th, on the left,—amounting

altogether to 5230 men. As there was not a sufficiency of boats, all this force did not

land at once; and one company of Highlanders, and detachments of other regiments, did not

get on shore till the return of the boats. The troops fixed upon to lead the way got into

the boats at two o’clock on the morning of the 8th of March, and formed in the rear

of the Mondovi, Captain John Stewart, which was anchored out of reach of shot from the

shore. By an admirable arrangement, each boat was placed in such a manner, that, when the

landing was effected, every brigade, every regiment, and even every company, found itself

in the proper station assigned to it. As such an arrangement required time to complete it,

it was eight o’clock before the boats were ready to move forward. Expectation was

wound up to the highest pitch, when, at nine o’clock, a signal was given, and all the

boats, with a simultaneous movement, sprung forward, under the command of the Hon. Captain

Alexander Cochrane. Although the rowers strained every nerve, such was the regularity of

their pace, that no boat got ahead of the rest.

At first the enemy did not believe that the

British would attempt a landing in the face of their lines and defences; but when the

boats had come within range of their batteries, they began to perceive their mistake, and

then opened a heavy fire from their batteries in front, and from the castle of Aboukir in

flank. To the showers of grape and shells, the enemy added a fire of musketry from 2500

men, on the near approach of the boats to the shore. In a short time the boats on the

right, containing the 23d, 28th, 42d, and 58th regiments, with the flank companies of the

40th, got under the elevated position of the enemy’s batteries, so as to be sheltered

from their fire, and meeting with no opposition from the enemy, who did not descend to the

beach, these troops disembarked and formed in line on the sea shore. Lest an irregular

fire might have created confusion in the ranks, no orders were given to load, but the men

were directed to rush up the face of the hill and charge the enemy.

When the word was given to advance, the

soldiers sprung up the ascent, but their progress was retarded by the loose dry sand which

so deeply covered the ascent, that the soldiers fell back half a pace every step they

advanced. When about half way to the summit, they came in sight of the enemy, who poured

down upon them a destructive volley of musketry. Redoubling their exertions, they gained

the height before the enemy could reload their pieces; and, though exhausted with fatigue,

and almost breathless, they drove the enemy from their position at the point of the

bayonet. A squadron of cavalry then advanced and attacked the Highlanders, but they were

instantly repulsed, with the loss of their cornmander. A scattered fire was kept up for

some time by a party of the enemy from behind a second line of small sand-hills, but they

fled in confusion on the advance of the troops. The Guards and first brigade having landed

on ground nearly on a level with the water, were immediately attacked,—the first by

cavalry, and the 54th by a body of infantry, who advanced with fixed bayonets. The

assailants were repulsed.

In this brilliant affair the British had 4

officers, 4 sergeants, and 94 rank and file killed, among whom were 31 Highlanders; 26

officers, 34 sergeants, 5 drummers, and 450 rank and file wounded; among whom were, of the

Highlanders, Lieutenant-Colonel James Stewart, Captain Charles Macquarrie, Lieutenants

Alexander Campbell, John Dick, Frederick Campbell, Stewart Campbell, Charles Campbell,

Ensign Wilson, 7 sergeants, 4 drummers, and 140 rank and file.’

The venerable commander-in-chief; anxious to

be at the head of his troops, immediately left the admiral’s ship, and on reaching

the shore, leaped from the boat with the vigour of youth. Taking his station on a little

sand-hill, he received the congratulations of the officers by whom he was surrounded, on

the ability and firmness with which he had conducted the enterprise. The general, on his

part, expressed his gratitude to them for "an intrepidity scarcely to be

paralleled," and which had enabled them to overcome every difficulty.

[When the boats were about to start, two

young French field officers, who were prisoners on board the Minotaur, Captain Louis, went

up to the rigging "to witness, as they said, the last sight of their English friends.

But when they saw the troops land, ascend the hill, and force the defenders at the top to

fly, the love of their country and the honour of their arms overcame their new friendship:

they burst into tears, and with a passionate exclamation of grief and surprise ran down

below, and did not again appear on deck during the day. "—Stewart’s

Sketches].

["The great waste of ammunition," says General

Stewart, "and the comparatively little execution of musketry, unless directed by a

steady hand, was exemplified on this occasion. Although the sea was as smooth as glass,

with nothing to interrupt the aim of those who fired,—although the line of musketry

was so numerous, that the soldiers compared the fall of the bullets on the water to boys

throwing handfuls of pebbles into a mill-pond,—and although the spray raised by the

cannon-shot and shells, when they struck the water, wet the soldiers in the

boats,—yet, of the whole landing force, very few were hurt and of the 42d one man

only was killed, and Colonel James Stewart and a few soldiers wounded. The noise and foam

raised by the shells and large and small shot, compared with the little effect thereby

produced, afford evidence of the saving of lives by the invention of gunpowder; while the

fire, noise, and force, with which the bullets flew, gave a greater sense of danger than

in reality had any existence. That eight hundred and fifty men (one company of the

Highlanders did not land in the first boats) should force a passage through such a shower

of balls and bomb-shells, and only one man killed and five wounded, is certainly a

striking fact." Four-fifths of the loss of the Highlanders was sustained before they

reached the top of the hill. General Stewart, who then commanded a company in the 42d,

says that eleven of his men fell by the volley they received when mounting the ascent].

The remainder of the army landed in the

course of the evening, but three days elapsed before the provisions and stores were

disembarked. Menou, the French commander, availed himself of this interval to collect more

troops and strengthen his position; so that on moving forward on the evening of the 12th,

the British found him strongly posted among sand-hills, and palm and date trees, about

three miles east of Alexandria, with a force of upwards of 5000 infantry, 600 cavalry, and

30 pieces of artillery.

Early on the morning of the 13th, the troops

moved forward to the attack in three columns of regiments. At the head of the first column

was the 90th or Perthshire regiment; the 92d or Gordon Highlanders formed the advance of

the second; and the reserve marching in column covered the movements of the first line, to

which it ran parallel. When the army had cleared the date trees, the enemy, leaving the

heights, moved down with great boldness on the 92d, which had just formed in line. They

opened a heavy fire of cannon and musketry, which the 92d quickly returned; and although

repeatedly attacked by the French line, supported by a powerful artillery, they maintained

their ground singly till the whole line came up. Whilst the 92d was sustaining these

attacks from the infantry, the French cavalry attempted to charge the 90th regiment down a

declivity with great impetuosity. The regiment stood waiting their approach with cool

intrepidity, and after allowing the cavalry to come within fifty yards of them, they

poured in upon them a well-directed volley, which so completely broke the charge that only

a few of the cavalry reached the regiment, and the greater part of these were instantly

bayoneted; the rest fled to their left, and retreated in confusion. Sir Ralph Abercromby,

who was always in front, had his horse shot under him, and was rescued by the 90th

regiment when nearly surrounded by the enemy’s cavalry.

After forming in line, the two divisions

moved forward — the reserve remaining in column to cover the right flank. The enemy

retreated to their lines in front of Alexandria, followed by the British army. After

reconnoitring their works, the British commander, conceiving the difficulties of an attack

insuperable, retired, and took up a position about a league from Alexandria. The British

suffered severely on this occasion. The Royal Highlanders, who were only exposed to

distant shot, had only 3 rank and file killed, and Lieutenant-Colonel Dickson, Captain

Archibald Argyll Campbell, Lieutenant Simon Fraser, 3 sergeants, 1 drummer, and 23 rank

and file wounded.

In the position now occupied by the British

general, he had the sea on his right flank, and the Lake Maadie on his left. On the right

the reserve was placed as an advanced post; the 58th possessed an extensive ruin, supposed

to have been the palace of the Ptolemies. On the outside of the ruin, a few paces onward

and close on the left, was a redoubt, occupied by the 28th regiment. The 23d, the flank

companies of the 40th, the 42d, and the Corsican Rangers, were posted 500 yards towards

the rear, ready to support the two corps in front. To the left of this redoubt a sandy

plain extended about 300 yards, and then sloped into a valley. Here, a little retired

towards tho rear, stood the cavalry of the reserve; and still farther to the left, on a

rising ground beyond the valley, the Guards were posted, with a redoubt thrown up on their

right, a battery on their left, and a small ditch or enbankment in front, which connected

both. To the left of the Guards, in echelon, were posted the Royals, 54th (two

battalions), and the 92d; then the 8th or Kings, 18th or Royal Irish, 90th, and 13th. To

the left of the line, and facing the lake at right angles, were drawn up the 27th or

Enniskillen, 79th or Cameron Highlanders and 50th regiment. On the left of the second line

were posted the 30th, 89th, 44th, Dillon’s, De Roll’s, and Stuart’s

regiments; the dismounted cavalry of the 12th and 26th dragoons completed the second line

to the right. The whole was flanked on the right by four cutters, stationed close to the

shore. Sutch was the disposition of the army from the 14th till the evening of the 20th,

during which time the whole was kept in constant employment, either in performing military

duties, strengthening the position—which had few natural advantages—by the

erection of batteries, or in bringing forward cannon, stores, and provisions. Along the

whole extent of the line were arranged two 24 pounders, thirty-two field-pieces, and one

24 pounder in the redoubt occupied by the 28th.

The enemy occupied a parallel position on a

ridge of hills extending from the sea beyond the left of the British line, having the town

of Alexandria, Fort Caffarell, and Pharos, in the rear. General Lanusse was on the left of

Menou’s army with four demi-brigades of infantry, and a considerable body of cavalry

commanded by General Roise. General Regnier was on the right with two demi-brigades and

two regiments of cavalry, and the centre was occupied by five demi-brigades. The advanced

guard, which consisted of one demibrigade, some light troops, and a detachment of cavalry,

was commanded by General D’Estain.

Meanwhile, the fort of Aboukir was blockaded

by the Queen's regiment, and, after a slight resistance, surrendered to Lord Dalhousie on

the 18th. To replace the Gordon Highlanders, who had been much reduced by previous

sickness, and by the action of the 13th, the Queen’s regiment was ordered up on the

evening of the 20th. The same evening the British general received accounts that General

Menou had arrived at Alexandria with a large reinforcement from Cairo, and was preparing

to attack him.

Anticipating this attack, the British army

was under arms at an early hour in the morning of the 21st of March, and at three

o’clock every man was at his post. For half an hour no movement took place on either

side, till the report of a musket, followed by that of some cannon, was heard on the left

of the line. Upon this signal the enemy immediately advanced, and took possession of a

small picquet, occupied by part of Stuart’s regiments but they were instantly driven

back. For a time silence again prevailed, but it was a stillness which portended a deadly

struggle. As soon as he heard the firing, General Moore, who happened to be the general

officer on duty during the night, had galloped off to the left; but an idea having struck

him as he proceeded, that this was a false attack, he turned back and had hardly returned

to his brigade when a loud huzza, succeeded by a roar of musketry, showed that he was not

mistaken. The morning was unusually dark, cloudy, and close. The enemy advanced in silence

until they approached the picquets, when they gave a shout and pushed forward. At this

moment Major Sinclair, as directed by Major-General Oakes, advanced with the left wing of

the 42d, and took post on the open ground lately occupied by the 28th regiment, which was

now ordered within the redoubt. Whilst the left wing of the Highlanders was thus drawn up,

with its right supported by the redoubt Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander Stewart was directed

to remain with the right wing 200 yards in the rear, but exactly parallel to the left

wing. The Welsh Fusileers and the flank companies of the 40th moved forward, at the same

time, to support the 58th, stationed in the ruin. This regiment had drawn up in the chasms

of the ruined walls, which were in some parts from ten to twenty feet high, under cover of

some loose stones which the soldiers had raised for their defence, and which, though

sufficiently open for the fire of musketry, formed a perfect protection against the

entrance of cavalry or infantry. The attack on the ruin, the redoubt, and the left wing of

the Highlanders, was made at the same moment, and with the greatest impetuosity; but the

fire of the regiments stationed there, and of the left wing of the 42d, under Major

Stirling, quickly checked the ardour of the enemy. Lieutenant-Colonels Paget of the 28th,

and Houston of the 58th, after allowing the enemy to come quite close, directed their

regiments to open a fire, which was so well-directed and effective, that the enemy were

obliged to retire precipitately to a hollow in their rear.

During this contest in front, a column of the enemy, which

bore the name of the "Invincibles," preceded by a six-poundei, came silently

along the hollow interval from which the cavalry picquet had retired, and passed between

the left of the 42d and the right of the Guards. Though it was still so dark that an

object could not be properly distinguished at the distance of two yards, yet, with such

precision did this column calculate its distance and line of march, that on coming in line

with the left wing of the Highlanders, it wheeled to its left, and marched in between the

right and left wings of the regiment, which were drawn up in parallel lines. As soon as

the enemy were discovered passing between the two lines, Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander

Stewart instantly charged them with the right wing to his proper front, whilst the

rear-rank of Major Stirling’s force, facing to the right about, charged to the rear.

Being thus placed between two fires, the enemy rushed forward with an intention of

entering the ruin, which they supposed was unoccupied. As they passed the rear of the

redoubt the 28th faced about and fired upon them. Continuing their course, they reached

the ruin, through the openings of which they rushed, followed by the Highlanders, when the

58th and 48th, facing about as the 28th had done, also fired upon them. The survivors

(about 200), unable to withstand this combined attack, threw down their arms and

surrendered. Generals Moore and Oakes were both wounded in the ruin, but were still able

to continue in the exercise of their duty. The former, on the surrender of the "

Invincibles," left the ruin, and hurried to the left of the redoubt, where part of

the left wing of the 42d was busily engaged with the enemy after the rear rank had

followed the latter into the ruins. At this time the enemy were seen advancing in great

force on the left of the redoubt, apparently with an intention of making another attempt

to turn it. On perceiving their approach, General Moore immediately ordered the

Highlanders out of the ruins, and directed them to form line in battalion on the flat on

which Major Stirling had originally formed, with their right supported by the redoubt. By

thus extending their line they were enabled to present a greater front to the enemy; but,

in consequence of the rapid advance of the latter, it was found necessary to check their

progress even before the battalion had completely formed in line. Orders were therefore

given to drive the enemy back, which were instantly performed with complete success.

Encouraged by the commander-in-chief, who

called out from his station, "My brave highlanders, remember your country, remember

your forefathers!" they pursued the enemy along the plain; but they had not proceeded

far, when General Moore, whose eye was keen, perceived through the increasing clearness of

the atmosphere, fresh columns of the enemy drawn up on the plain beyond with three

squadrons of cavalry, as if ready to charge through the intervals of their retreating

infantry. As no time was to be lost, the general ordered the regiment to retire from their

advanced position, and re-form on the left of the redoubt. This order, although repeated

by Colonel Stewart, was only partially heard in consequence of the noise of the firing;

and the result was, that whilst the companies who heard it retired on the redoubt, the

rest hesitated to follow. The enemy observing the intervals between these companies,

resolved to avail themselves of the circumstance, and advanced in great force. Broken as

the line was by the separation of the companies, it seemed almost impossible to resist

with effect an impetuous charge of cavalry; yet every man stood firm. Many of the enemy

were killed in the advance. The companies, who stood in compact bodies, drove back all who

charged them, with great loss. Part of the cavalry passed through the intervals, and

wheeling to their left, as the " Invincibles" had done early in the morning,

were received by the 28th, who, facing to their rear, poured on them a destructive fire,

which killed many of them. It is extraordinary that in this onset only 13 Highlanders were

wounded by the sabre,—a circumstance to be ascribed to the firmness with which they

stood, first endeavouring to bring down the horse, before the rider came within

sword-length, and then despatching him with the bayonet, before he had time to recover his

legs from the fall of the horse.

[Concerning this episode in the fight, and the capture of the

standard of the "Invincibles" by one of the 42d, we shall here give the

substance of the narrative of Andrew Dowie, one of the regiment who was prresent and saw

the whole affair. We take it from Lieutenant-Colonel Wheatley’s Memoranda, and we

think our readers may rely upon it as being a fair statement of the circumstances. It was

written in 1845, in letter to Sergeant-Major Drysdale of the 42d, who went through the

whole of the Crimean and Indian Mutiny campaigns without being one day absent, and who

died at Uphall, near Edinburgh. Major and Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel in the regiment

—on the 4th July 1865 —While Dowie was inside of the ruin above mentioned, he

observed an officer with a stand of colours, surrounded by a group of some 30 men. He ran

and told Major Stirling of this, who advanced towards the French officer, grasped this

colours, carried them off, and handed them to Sergeant Sinclair of the 42d Grenadiers,

telling him to take them to the rear of the left wing, and display them. The major then

ordered all out of the fort to support the left wing, which was closely engaged. Meantime,

some of the enemy seeing Sinclair with the colours, made after and attacked him. He

defended himself to the utmost till he got a sabre-cut on the back of the neck, when he

fell with the colours among the killed and wounded. Shortly afterwards the German

regiment, commanded by Sir John Stewart, came from the rear line to the support of the

42d, and in passing through the killed and, wounded, one Anthony Lutz picked up the

colours, stripped them off the staff, wound them round his body, and in the afternoon took

them to Sir Ralph’s son, and it was reported received some money for them. In 1802

this German regiment (97th or Queen’s Own arrived at Winchester, where this Anthony

Lutz, in a quarrel with one of his comrades, stabbed him with a knife, was tried by civil

law, and sentence of death passed upon him. His officers, to save his life, petitioned the

proper authorities, stating that it was he who took the ‘ Invincible Colours."

Generals Moore and Oakes (who had commanded the brigade containing the 42d), then in

London, wrote to Lieut. -Col. Dickson, who was with the regiment in Edinburgh Castle, and

a court of inquiry was held on the matter, the result of the examination being in

substance what I has just been narrated. Sergeant Sinclair was promoted to ensign in 1803;

was captain in the 81st from 1813 to 1816, when he retired on half pay, and died in 1831].

Enraged at

the disaster which had befallen the elite of his cavalry, General Menou ordered forward a

column of infantry, supported by cavalry, to make a second attempt on the position; but

this body was repulsed at all points by the Highlanders. Another body of cavalry now

dashed forward as the former had done, and met with a similar reception, numbers falling,

and others passing through to the rear, where they were again overpowered by the 28th. It

was impossible for the Highlanders to withstand much longer such repeated attacks,

particularly as they were reduced to the necessity of fighting every man on his own

ground, and unless supported they must soon have been destroyed. The fortunate arrival of

the brigade of Brigadier-General Stuart, which advanced from the second line, and formed

on the left of the Highlanders, probably saved them from destruction. At this time the

enemy were advancing in great force, both in cavalry and infantry, apparently determined

to overwhelm the handful of men who had hitherto baffled all their efforts. Though

surprised to find a fresh and more numerous body of troops opposed to them, they

nevertheless ventured to charge, but were again driven back with great precipitation.

It was now eight o’clock in the morning;

but nothing decisive had been effected on either side. About this time the British had

spent the whole of their ammunition; and not being able to procure an immediate supply,

owing to the distance of the ordnance-stores, their fire ceased,—a circumstance which

surprised the enemy, who, ignorant of the cause, ascribed the cessation to design.

Meanwhile, the French kept up a heavy and constant cannonade from their great guns, and a

straggling fire from their sharp-shooters in the hollows, and behind some sand-hills in

front of the redoubt and ruins. The army suffered greatly from the fire of the enemy,

particularly the Highlanders, and the right of General Stuart’s brigade, who were

exposed to its full effect, being posted on a level piece of ground over which the

cannon-shot rolled after striking the ground, and carried off a file of men at every

successive rebound. Yet not withstanding this havoc no man moved from his position except

to close up the gap made by the shot, when his right or left hand man was struck down.

At this stage of the battle the proceeedings

of the centre may be shortly detailed. The enemy pushed forward a heavy column of

infantry, before the dawn of day, towards the position occupied by the Guards. After

allowing them to approach very close to his front, General Ludlow ordered his fire to be

opened, and his orders were executed with such effect, that the enemy retired with

precipitation. Foiled in this attempt, they next endeavoured to turn the left of the

position; but they were received and driven back with such spirit by the Royals and the

right wing of the 54th, that they desisted from all further attempts to carry it. They,

however, kept up an irregular fire from their cannon and sharp-shooters, which did some

execution. As General Regnier, who commanded the right of the French line, did not

advance, the left of the British was never engaged. He made up for this forbearance by

keeping up a heavy cannonade, which did considerable injury.

Emboldened

by the temporary cessation of the British fire on the right, the French sharpshooters came

close to the redoubt; but they were thwarted in their designs by the opportune arrival of

ammunition. A fire was immediately opened from the redoubt, which made them retreat with

expedition. The whole line followed, and by ten o’clock the enemy had resumed their

original position in front of Alexandria. After this, the enemy despairing of success,

gave up all idea of renewing the attack, and the loss of the commander-In-chief, among

other considerations, made the British desist from any attempt to force the enemy to

engage again.

Sir Ralph Abercomby, who had taken his

station in front early in the day between the right of the Highlanders and the left of the

redoubt, having detached the whole of his staff, was left alone. In this situation two of

the enemy’s dragoons dashed forward, and drawing up on each side, attempted to lead

him away prisoner. In a struggle which ensued he received a blow on the breast; but with

the vigour and strength of arm for which he was distinguished, he seized the sabre of one

of his assailants, and forced it out of his hard. A corporal (Barker) of the 42d coming up

to his support at this instant, for lack of other ammunition, charged his piece with

powder and his ramrod, shot one of the dragoons, and the other retired.

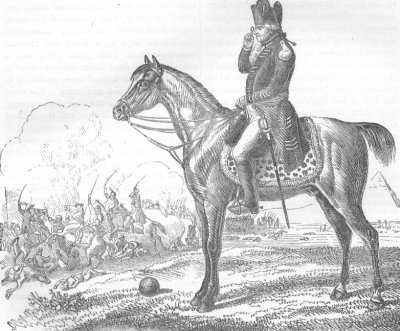

Sir Ralph Abercromby in Egypt. From Kay's Edinburgh Portraits.

The general afterwards dismounted from his

horse though with difficulty; but no person knew that he was wounded, till some of the

staff who joined him observed the blood trickling down his thigh. A musket-bail had

entered his groin, and lodged deep in the hip-joint. Notwithstanding the acute pain which

a wound in such a place must have occasioned, he had, during the interval between the time

he had been wounded and the last charge of cavalry, walked with a firm and steady step

along the one of the Highlanders and General Stuart’s brigade, to the position of the

Guards in the centre of the line, where, from its elevated position, he had a full view of

the whole field of battle, and from which place be gave his orders as if nothing had

happened to him. In his anxiety about the result of the battle, seemed to forget that he

had been hurt; but after victory had declared in favour of the British army, he became

alive to the danger of his situation, and in a state of exhaustion, lay down on a little

sand-hill near the battery.

In this situation he was surrounded by the

generals and a number of officers. The soldiers were to be seen crowding round this

melancholy group at a respectful distance, pouring out blessings on his head, and prayers

for his recovery. His wound was now examined, and a large incision was made to extract the

ball but it could not be found. After this operation he was put upon a litter, and carried

onboard the Foudroyant, Lord Keith’s ship, where he died on the morning of the 28th

of March. "As his life was honourable, so his death was glorious. His memory will be

recorded in the annals of his country, will be sacred to every British soldier, and

embalmed in the memory of a grateful posterity."

The loss of the British, of whom scarcely

6000 were actually engaged, was not so great as might have been expected. Besides the

commander-in-chief, there were, killed 10 officers, 9 sergeants, and 224 rank and file;

and 60 officers, 48 sergeants, 3 drummers, and 1082 rank and file, were wounded. Of the

Royal Highlanders, Brevet-Major Robert Bisset, Leutenants Colin Campbell, Robert Anderson,

Alexander Stewert, Alexander Donaldson, and Archibald M’Nicol, and 48 rank and file,

were killed; and Major James Stirling, Captain David Stewart, Leutenant Hamilton Rose, J.

Millford Sutherland, A.M Cuningham, Frederick Campbell, Maxwell Grant, Ensign William

Mackenzie, 6 sergeants, and 247 rank and file wounded. As the 42d was more exposed than

any of the other regiments engaged, and sustained the brunt of the battle, their loss was

nearly three times the aggregate amount of the loss of all the other regiments of the

reserve. The total loss of the French was about 4000 men.

General Hutchinson, on whom the command of

the British army now devolved, remained in the position before Alexandria for some time,

during which a detachment under Colonel Spencer took possession of Rosetta. Having

strengthened his position between Alexandria and Aboukir, General Hutchinson transferred

his headquarters to Rosetta, with a view to proceed against Rhamanieh, an important post,

commanding the passage of the Nile, and preserving the communication between Alexandria

and Cairo. The general left his camp on the 5th of May to attack Rhamanieh; but although

defended by 4000 infantry, 800 cavalry, and 32 pieces of cannon, the place was evacuated

by the enemy on his approach.

The commander-in-chief proceeded to Cairo,

and took up a position four miles from that city on the 16th of June. Belliard, the French

general, had made up his mind to capitulate whenever he could do so with honour; and

accordingly, on the 22d of June, when the British had nearly completed their approaches,

he offered to surrender, on condition of his army being sent to France with their arms,

luggage, and effects.

Nothing now remained to render the conquest

of Egypt complete but the reduction of Alexandria. Returning from Cairo, General

Hutchinson proceeded to invest that city. Whilst General Coote, with nearly half the army,

approached to the westward of the town, the general himself advanced from the eastward.

General Menou, anxious for the honour of the French arms, at first disputed the advances

made towards his lines; but finding himself surrounded on two sides by an army of 14,500

men, by the sea on the north, and cut off from the country on the south by a lake which

had been formed by breaking down the dike between the Nile and Alexandria, he applied for,

and obtained, on the evening of the 26th of August, an armistice of three days. On the 2d

of September the capitulation was signed, the terms agreed upon being much the same with

those granted to General Beliard.

After the French were embarked, immediate arrangements were

made for settling in quarters the troops that were to remain in the country, and to embark

those destined for other stations. Among these last were the three Highland regiments. The

42d landed at Southhampton, and marched to Winchester. With the exception of those who

were affected with ophthalmia, all the men were healthy. At Winchester, however, the men

caught a contagious fever, of which Captain Lamont and several privates died.

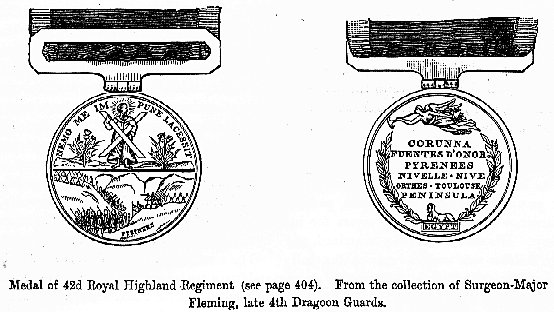

Medal to the Officers of the 42d Royal

Highlanders for services in Egypt

"At this period,"

says General Stewart, "a circumstance occurred which caused come

conversation on the French standard taken at Alexandria. The Highland Society

of London, much gratified with the accounts given of the conduct of their

countrymen in Egypt, resolved to bestow on them some mark of their esteem and

approbation. The Society being composed of men of the first rank and character

in Scotland, and including several of the royal family as members, it was

considered that such an act would be honourable to the corps and agreeable to

all. It was proposed to commence with the 42d as the oldest of the Highland

regiments, and with the others in succession, as their service offered an

opportunity of distinguishing themselves. Fifteen hundred pounds were

immediately subscribed for this purpose. Medals were struck with a head of Sir

Ralph Abercromby, and some emblematical figure’s on the obverse.. A superb

piece of plate was likewise ordered. While these were in preparation, the

Society held a meeting, when Sir John Sinclair, with the warmth of a clansman,

mentioned his namesake, Sergeant Sinclair, as having taken or having got

possession of the French standard, which had been brought home. Sir John being

at that time ignorant of the circumstances, made no mention of the loss of the

ensign which the sergeant had gotten in charge. This called forth the claim of

Lutz, already referred to, accompanied with some strong remarks by Cobbett,

the editor of the work in which the claim appeared. The Society then asked an

explanation from the officers of the 42d. To this very proper request a reply

was given by the officers who were then present with the regiment. The

majority of these happened to be young men, who expressed, in warm terms,

their surprise that the Society should imagine them capable of countenancing

any statement implying that they had laid claim to a trophy to which they had

no right. This misapprehension of the Society’s meaning brought on a

correspondence, which ended in an interruption of farther communication for

many years.

|