|

By Robert Hutchison of Carlowrie.

[Premium—Five Sovereigns.]

Whatever difference of opinion may exist in the minds

of arboriculturists as to the indigenous nature of some other species of

hard-wooded trees to Scotland, or even to Britain, there can be no doubt

regarding the walnut having been an importation and a foreign

acquisition to our Sylva. Old and large examples at the present day are

few in number, and, like the Spanish chestnuts,—with which in point of

introduction the walnut seems to be coeval,—are generally found around

ruined monastic buildings and foundations, or adjoining the castellated

remains of the strongholds of feudal barons of the Middle Ages, in sites

which appear to have been carefully selected, with due regard to

prominence and yet shelter, where the cherished nut tended with care,

and probably the memento of some distant pilgrimage, might remind the

old monk of some foreign shrine, or recall to the memory of the gallant

knight-errant in after years in his native land, the grateful shade and

refreshing fruit of its parent tree, under whose umbrageous branches he

had rested after the toils of the battle-field. Some authorities ascribe

the introduction of the walnut to the Romans during their occupation of

Britain, but however this theory may hold good as regards the southern

parts of England, it cannot be supported by either fact or inference, if

we take the oldest survivors in Scotland as living witnesses, or notice

the total absence of all traces of any remains, or even of later

specimens existing at or near to any Roman station in Scotland.

Few, if any, walnuts appear to have existed in this

country, north of the Tweed, earlier than about the year 1600. It is a

curious fact, that Dr Walker, who wrote his Catalogue after about forty

years of patient compilation, mentions only four " remarkable "

walnut trees in Scotland, and Sir Thomas Dick Lauder in 1826 adds none

to the list which the old Professor had collected. The cause of this

scarcity of good examples existing in Scotland about the beginning of

the century will be afterwards referred to, and probable reasons

assigned for it, but meantime, we may glance at these old walnuts

noticed and recorded by Walker, and endeavour to identify any of them at

the present day, and notice their growths and condition. It should be

observed also, that the otherwise very fastidious arborist and collector

Dr Walker condescends to notice in his scanty list, three trees of no

notable size whatever, thus showing that very few trees of dimensions

worth recording were known to him from 1760 to 1790 ; and so minute and

exacting an inquirer into all nature's secrets was Dr Walker, that if

many fine trees of the walnut species had then existed in this country,

even at wide and distant points, his industrious and intelligent

investigations would have led him to them, and he would have certainly

discovered and recorded them. Walker's first mentioned walnut is one

growing in the garden at Lochnell in Argyleshire, which, in July 1771,

girthed 3 feet 3 inches at 4 feet from the ground, and was 25 feet in

height, and was then known to be exactly thirty-six years old. It is to

be regretted that repeated inquiries made as to the existence and

condition and size of this tree at the present day, for the purpose of

this paper, have been met with no response regarding it.

Walker's second walnut grew at Alva, Stirlingshire.

It was planted in the garden by Sir John Erskine anno 1715, in presence

of his brother the Lord Justice Clerk Tinwald, afterwards proprietor of

the estate. In October 1760, at 2 feet from the ground, it girthed 5

feet 4 inches. This tree we find, after careful inquiry, is departed,

but neither date nor manner of its decease has been preserved or

recorded. Walker next refers to "a number of walnut trees at Cames" (Kaimes),

isle of Bute, "vigorous and well grown," which in September 1771 were

about seventy years old. "They were then," he remarks, "between 50 and

60 feet high, and the largest of them girthed at 4 feet from the ground,

6 feet 1 inch." On inquiry and careful investigation by Mr Kay, the able

and intelligent wood manager on the Kaimes estate, we have ascertained

that none of these trees now exist. When they were felled, or how they

disappeared, not even the oldest inhabitant can tell, so much had they

probably been regarded as merely ordinary hard-wooded trees at the time

of their disposal. It is, however, somewhat remarkable than in the

island of Bate, a district isolated, and replete with many very

remarkably large and notable trees of almost every variety, no instance

of a walnut of anything like timber size has been obtained. Thus it is

that frequently in the most likely localities, as regards soil, climate,

and other circumstances, the enthusiastic explorer is disappointed,

while in the most unexpected quarters, often rare and remarkable

specimens of different descriptions of trees are found. And as a further

instance of this, we need only notice Walker's fourth, and indeed only

large walnut, — which "grows," says he, "before

the front of Kinross House, in Kinross-shire, and

in "September 1796, measured at 4 feet from the ground 9 feet 6 inches

in circumference." He further adds—"The

house of Kinross was finished by Sir William Bruce in 1684, and the

tree appears to be coeval with the house. It is probably

the oldest and largest walnut tree in Scotland, and is evidently on the

decay, but whether this proceeds from accident or from age it is

uncertain." Gilpin, in 1791, in noticing this tree (but without

reference to its girth at that date), says, "there are many walnut trees

of a size, equal if not superior to that of this tree.È From recent

inquiries made for the purposes of this paper,—and seeing it is not

mentioned in the Highland Society's Catalogue of Old and Eemarkable

Trees, collected in 1863,—we find, and are glad to state that the old

veteran is still alive, and in considerable vigour. It now measures at 4

feet from the ground 23 feet in circumference. It is unfortunately shorn

of much of its grandeur, from having lost some of its largest limbs, but

still evinces considerable vitality.

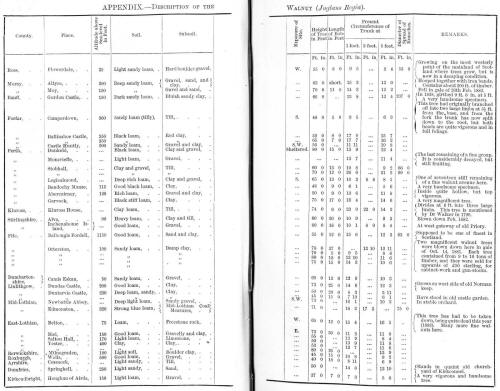

Of the more recently collected statistics of the

walnut in Scotland, we may recapitulate those of the Highland Society's

list, which we have been able to trace, before proceeding to consider

and describe existing notable specimens at the present day, given in the

appendix to this paper, and not hitherto recorded. The number we have

been able to tabulate of trees in Scotland at the present day in the

appendix is 39,—while those given, and many of them of smaller

dimensions, in the returns collected in 1863, number only 13. The

venerable tree which is recorded as growing at Eccles, Dumfriesshire,

and which in 1863 girthed 22 feet at the base and 13 feet at 12 feet

from the ground, is now no more, having been blown down in a gale a few

years ago. The old walnut recorded in 1863, "in a vigorous condition,"

growing near the mansion house of Belton, and then 65 feet high, and

girthing at 5 feet from the ground 15 feet 4 inches and at 7 feet 16

feet 8 inches, was measured in 1880, and found to be at 5 feet from the

ground 16 feet 1 inch, and although the foliage was healthy, the tree

had evidently ceased to grow, many branches giving symptoms of decay.

The severe winter of 1880-81 proved too much for this hoary veteran, and

he died its victim, and was taken down last year. It has not been found

possible to identify precisely any of the other specimens given in the

catalogue of: 1863, or of those in Loudon's scanty list made up in 1834,

Coming now to the descriptions of the old walnuts tabulated in the

appendix to this report, we notice first, the old tree still growing,

but in a very decaying condition, at Flowerdale, Ross-shire. It still

exhibits the remains of a fine tree for that latitude, and considering

the situation it occupies. It girths 9 feet 5 inches at 1 foot from the

ground, and 8 feet 4 inches at 5 feet, and is now 55 feet in height. It

stands in front of the house of Flowerdale, in a sheltered glen only

about a quarter of a mile from the sea. and about from 30 to 40

feet above its level. The site is the most westerly

point on the mainland of Scotland where trees grow. Nothing is certainly

known of its age, but from circumstances connected with the history of

the Mackenzie family, it was in all probability planted between 1755 and

1760. Another fine old walnut in the north of Scotland is at Altyre

(Morayshire). Viewed in 1881, this venerable patriarch, which stands

close to the mansion house, has evidently seen its brightest and best

days; but hooped as it is with strong iron clasps, it may stand the

blasts of many a winter yet. It is quite hollow, has three large limbs

still remaining, a fourth having been removed as it threatened an

outhouse of the mansion, and is now, though crowned with a leafy head,

evidently "living on its bark." It girthed 15 feet 2 inches at 1 foot

and 13 feet at 4 feet from the ground. The soil is a deep sandy loam,

recumbent on gravel. It yields large crops of fruit, which ripen almost

ever year. There are other trees in Morayshire of nearly similar

dimensions, but on account of the soil and situation which they occupy,

being somewhat later, it is only in very favourable seasons that their

fruit becomes fit for dessert. Since the notes for this paper were

prepared, it is unfortunate to have to record regarding this interesting

old walnut, and also regarding the one at Moy (Morayshire), also

mentioned in the appended list of old trees, that both veterans

succumbed to the wrestling hurricane of 26th February 1882. The largest

walnuts, and probably with few exceptions the finest trees as specimens

found in Scotland, are in Perthshire. Referring to those noticed in the

appended list, specially may be noted the fine example growing at

Moncrieffe, in a light loam soil, upon a gravel subsoil. This tree,

which is extremely picturesque, is the last survivor of a fine group

which occupied a space of ground, supposed to have been adjoining the

original garden. The largest erect tree of the group measured in 1880,

13 feet 7 inches at 1 foot from the base, and 10 feet 9 inches at

5 feet from the ground. The trees composing this group had to be taken

down in April 1881, for the extension of an avenue, and the only

survivor left, and already referred to, is now, at 5 feet from the

ground, 11 feet 4 inches in circumference. It

is, however, considerably decayed and lying in a procumbent position on

the ground, but it is still evincing its vitality by a good crop

of walnuts this season, well filled, and quite fit for table use.

The system of planting walnut trees in groups does

not appear to have been so common in Scotland during last century as in

England. It appears rather to have been the practice to plant in lines

or in straight rows at considerable distances apart, and this plan was

probably adopted from a belief that the heavy foliage and dense shadows

cast was inimical to the crops underneath and around, and an idea also

prevailed that the bitter juices contained in the falling leaves in

autumn were injurious to the soil. Traces, however, do exist where the

walnut has been planted to form avenues to old buildings. One of the

finest of these is still to be seen at Logiealmond, within two hundred

yards of the old mansion house. Many of the trees once forming this fine

and imposing old avenue were blown down during the great gale in

December 29, 1879, when the Tay Bridge disaster occurred; and one or two

also succumbed to the storms of last spring (January and February 1882).

There are, however, still seventeen trees standing, and at present four

of the last blown ones are lying on the ground as they fell. The trees,

reckoning from the concentric circles, are about 110 years of age ; the

largest still surviving measures, at 1 foot above the surface 10 feet 3

inches, at 3 feet it is 8 feet 8 inches; and at 5 feet, 8 feet 1 inch in

circumference. The seventeen trees will average from 6 to 10 feet in

circumference at 1 foot from the ground. The Kinross House walnut has

long been considered to be the largest tree of its species in Scotland;

but this is not so, for reference to the appended list will show that at

least one tree is larger. This premier walnut exists at Stobhall,

Perthshire. It is no less than 26 feet in girth at 1 foot and 21 feet 2

inches at 5 feet from the ground, with a massive bole 12 feet in length,

and a total height of 70 feet, and the diameter of its spread of

branches is 99 feet. It is in a vigorous condition. Another picturesque

old Perthshire walnut is to be seen at Abercairney near Crieff, It

stands near the site of the old mansion house. The inside of the trunk

and heavy limbs are very much decayed and quite hollow, so that a

full-grown man can stand inside the trunk, while the holes in the giant

limbs are the haunts of many species of the feathered tribe. The top of

the tree appears quite vigorous, and when in foliage looks perfectly

healthy. It grows in a good loamy soil, upon clay and gravel subsoil, at

an altitude of about 120 feet above sea-level.

Growing on the lonely island of Inchmahome, in the

lake of Menteith, are some interesting and picturesque old trees. They

are chiefly Spanish chestnuts, but amongst these are several walnuts

around the old garden of the priory. One fine specimen given in the

appendix, stands sentinel-like and confronting a large Spanish chestnut

at the western gateway of the priory. These two trees, as well as others

of the same species, have evidently been selected to fill special points

in what has in the Middle Ages been a well-laid out and artistically

arranged pleasure ground. The Spanish chestnuts on the island have been

already described in the chapter on that species, and need not now be

referred to. Mary, Queen of Scots, when a child, is said to have resided

for a time on this island; and part of the old garden, the quaint walks

of which are still traceable, with their boxwood edgings now grown into

trees 20 feet high, and fully 3 feet in girth, still bears the name of

"Queen Mary's bower," and "Queen Mary's garden." The walnut tree

referred to in this site is still sound to all appearance, and its

foliage looks quite healthy, while it fruits quite freely every year;

but from a crevice near the root on the east side, it is "oozing"

slightly, as old walnuts frequently do, indicating incipient internal

decay.

The finest walnuts in Fife are to be found at

Otterstone, near Aberdour; and at Balbougie, on the Fordell estate, near

Inverkeithing, there is a very handsome specimen. It is commonly

reported to be "the finest walnut tree in Scotland;" but however highly

it may rank in point of symmetry and general contour, its dimensions and

bulk of timber are eclipsed by several trees in other localities, and by

some of those to which reference has been made. It is, doubtless, a very

fine tree, and is 55 feet in height, with a bole of 12 feet, girthing 13

feet 6 inches at 1 foot and 12 feet 3 inches at 5 feet from the ground,

and the diameter of its spread of branches is 63 feet. The Otterstone

trees are more majestic, but unfortunately two of the finest of this

group fell in the awful gale of 14th October 1881. The largest of these

girthed no less than 16 feet at 12 feet from the ground, and one limb

alone was 13 feet 6 inches in girth, above the 12 feet measurement of

the bole. Each tree contained from 9 to 10 tons of beautifully sound and

valuable timber, great difficulty being experienced in transporting the

trunks to the railway, for, owing to their immense bulk, no janker in

the neighbourhood was either large or powerful enough to take in either

tree. The other tree, it may be stated, was 18 feet in girth at 20 feet

from the ground. The two trees were sold for a little over £50 for

cabinet work, and the roots were sold separately for gun-stocks, and

were most beautifully striated with richly coloured markings. The date

over the old doorway of the oldest portion of Otterstone mansion house

is 1589, and the walnuts, Spanish chestnuts, beeches, and other

magnificent timber trees adjoining the garden and house appear to be

coeval with this portion of the building,

We need only notice cursorily the walnuts of notable

appearance and dimensions to be found south of the Forth, as for

instance at Dundas Castle (Linlithgowshire), Duntarvie Castle (Linlithgowshire),

Newbattle Abbey and Edmonstone (Mid-Lothian), where the largest specimen

south of the Forth which we have been able to find still exist. It is

now 18 feet 2 inches at 1 foot and 17 feet 3 inches at 3 feet from the

ground. The soil is a strong blue loam, overlying the Mid-Lothian Coal

Measures, and the altitude of the site is 320 feet The tree is quite

vigorous. Fine examples are also recorded in the appendix at Belton,

Salton Hall, and Yester (East Lothian), and Milnegraden (Berwickshire).

At Wells (Roxburghshire), at an altitude of 500 feet, we find a very

fine tree with a beautiful bole of 15 feet, and girthing 10 feet 8

inches and 9 feet 2 inches at 1 and 5 feet respectively, showing the

suitability of the walnut to such an altitude. In the south-west

division of Scotland, fine trees are found at Cessnock Castle

(Ayrshire); and in the quaint old churchyard of Kirkconnel (Dumfries), a

picturesque old example still exists. It is 50 feet in height and girths

14 feet at 1 foot and 13 feet 10 inches at 5 feet above the ground. This

fine old tree is very much swayed to one side, from the soil and subsoil

both being sandy, and its three massive heavy limbs, which spring quite

horizontally from the trunk in one direction, with their additional

weight of foilage, being a severe strain upon the roots. It presents a

very weird appearance, and is an appropriate and suitable feature in the

foreground of the quaint old parish churchyard and its surroundings.

Having thus discussed the statistical features of the

principal trees in Scotland which we have been able to discover, we may

now proceed to notice the general characteristics of the walnut, and its

capabilities and value as a timber tree in Scotland.

The scarcity of old and remarkable walnuts in

Scotland, both at the present day and when the older authorities, such

as Evelyn, Walker, Selby, and Loudon collected statistics, has been

already referred to, and we may now, perhaps, consider if it is not

possible to discover the reason why a tree so valuable, alike for its

fruit and for the high price which its timber fetches when of large

size, is not found so extensively distributed over Scotland as one might

expect it to be, considering these special qualities, and its

suitability of habit and hardihood to our climate. That is it quite

hardy in Scotland there can be no doubt, for we find it even in the

northern counties of Scotland of large size, highly ornamental and

regularly fruiting, and in favourable autumns ripening its fruit

sufficiently for use as dessert. Nor is the soil unsuitable, for it will

thrive in almost any soil not water-logged, though it prefers, like the

oak, a strong adhesive loam, if the subsoil be well drained or free from

constant damp. Nor does altitude of site much affect it in this country,

for we find it of large size and quite hardy, flourishing at altitudes

of 500 feet and upwards in Scotland, as, for example, at Wells (Roxburgh

shire), where it is 10 feet at 1 foot and 9 feet 2 inches in

circumference at 5 feet from the ground (vide appendix); while at

Hawkstone Park, in Shropshire, at 1000 feet above sea-level, there is a

fine specimen 99 feet in height, and 22 feet in girth at 1 foot and 16

feet 6 inches at 5 feet from the ground, with a circumference of

branches embracing 279 feet, The causes of the scarcity of fine trees in

this country must, therefore, be looked for to other than climatic

reasons, and it may probably be accounted for on the following grounds.

The walnut in Britain never has been, at any period since its

introduction, propagated either as a timber or as a fruit tree to

anything like the same extent as it has been in France and other

continental countries, where from an early date every possible

encouragement has been given to its increase and cultivation. In this

country it has been more planted as an ornamental or park tree, its

chief use when cut down being for the manufacture of gun or musket

stocks, for which it was formerly in great demand, and for the supply of

which large quantities of walnut timber were imported from the

Continent. During the Peninsular wars, when many of the chief

continental ports and markets were closed against us, walnut timber in

Britain rose to an enormous price, as we may judge from the fact of a

single tree having been sold for £600 ; and as such prices offered

temptations which few proprietors were able to resist, a great number of

the finest walnut trees growing in this country were sacrificed about

that period to supply this trade. The deficiency and scarcity thus

created, as well as the high price, led to the introduction of the

American walnut timber, as well as of large supplies from the coasts of

the Black Sea, from whence any quantity can always be obtained, and at

prices lower than the timber can be grown for in Britain. Hence this

facility of procuring unlimited supplies from abroad has also done away

with the inducement to plant walnut trees in this country, where it is a

slow-growing and long-lived tree before reaching maturity as a timber

crop, and its cultivation as such may be said to be at an end in Great

Britain, and especially so in Scotland. The few specimens left to us of

any magnitude show well as trees of position, and for effect, in the

landscape, as well as for variety of foliage in mixed plantations, but

only as such will the walnut take its place among the forest trees of

Scotland in the future. Indeed, it is probably best adapted for planting

now as a park tree, or in hedge rows; for, in mixed plantations', its

enormous and deep-penetrating roots,—indicating great power and

resistance to the elements,—and its impatience of interference, evince

its unsocial habits, and mark it out as better fitted for an open or

exposed site ; and the only objection that can be stated to its

extensive introduction as an ornamental tree of first importance, is its

late period of coming into foliage in spring, and the early shedding of

its graceful light green pinnate leaves, which fall at the earliest

approach of the first autumnal frosts in our latitude. It does not admit

of being pruned at all when of any size; this operation, if necessary,

should only be done when the tree is quite young, and never close to the

main stem. Such treatment would be most injurious to the tree, and its

pernicious effects are observable in old trees which have come under our

notice in Scotland,—such a process of close-pruning having invariably

produced decay more or less at the lower edge of the wound, caused

doubtless by the wood being naturally capable only of slow

cicatrisation, and also from the soft loose texture of the young wood of

a tree which otherwise, when allowed to mature and ripen, produces a

timber of close-grained quality, of beautifully coloured and veined

appearance, and of the very finest quality for all artistic and

ornamental constructive purposes or for internal decoration and

furniture.

Evelyn states that it had been observed by a friend

of his that the "sap of the walnut tree rises and descends with the

sun's diurnal course (while it visibly slackens in the night), and more

plentifully at the root on the south side, though those roots cut on the

north side were larger and less distant from the trunk of the tree, and

that they not only distilled from the ends which were next the stem, but

from those that were cut off and separated," and which, he observes,

"does not happen in birch, or any other sap-yielding tree." (Evelyn's

Sylva (Hunter), vol. i. book i. p. 171.) It is a pity the

worthy and observant arborist does not tell us more of the details of

the experiments and observations by which he arrived at this conclusion

regarding this relation between the sun's diurnal course and the flow of

sap in the walnut tree, which he seems to point to as unique. May it not

have rather been, or be perhaps, due to lunar influence, if such a

phenomenon, as he alleges, exists at all, and afford inquiry, or fair

field for investigation into a matter of the most profound interest in

the economy of the vegetable kingdom and arboricultural world, viz., the

periodicity of the rise and fall of sap in trees throughout the

various periods of the moon's growth and decline in all months of

the year,—a function probably which, if better understood and

investigated, may be found to correspond to a similar law in the animal

kingdom for keeping alive and periodically revivifying and quickening

the latent forces of nature.

Many curious old and superstitious practices and

ideas prevailed in the last century regarding the walnut tree. These

were particularly common in Germany and in other countries of the

continent of Europe. In Frankfort and Hanau in Germany, until a very

recent time, no young farmer was permitted to marry till he had given

proof that he had himself planted, and was "the father" of a stated

number of walnut trees —a law which was most religiously enforced down

to very recent times, so great was the advantage supposed to be to the

inhabitants, and to the country generally, from the abundant presence of

the walnut tree. In olden times, again, the fruit of the walnut was wont

to be strewed by the bridegroom at a wedding,—to indicate that he had,

on entering his new phase of life, cast aside his boyish amusements and

games, or perhaps more likely to signify that his bride had desisted

from being any longer a votary of Diana, to whom the walnut tree was

sacred. From a very early date, the individual properties of the walnut,

in many parts of the Continent, were held in great veneration and

repute. It is almost ludicrous to recount some of its fancied curative

properties and the superstitious practices prevalent regarding these ;

and with respect to the various parts of the tree,—fruit, foliage, oil,

and bark. Thus,—a bitter decoction of the leaves and husks of the fruit

macerated in hot water, and spread upon lawns or garden walks, would

destroy worms and slugs without injuring the greensward. The water of

the husks was believed to be an unfailing antidote against all

pestilential infections, and that of the leaves to heal inveterate

ulcers. The green husks of the fruit boiled used to make a good dye, of

a deep yellow colour without any mixture. A distillation of walnut

leaves with honey and urine would make hair to grow upon bald heads. The

kernel masticated, if applied to the bite of a suspected mad dog, and

after it has lain for three hours, if cast to poultry, they will die if

they eat it, should the dog have been mad. In Italy, at the present day,

the country people drink a pint of fresh walnut oil to cure any pain in

the side or liver, and are said to receive immediate relief; but "more

famous," says Evelyn, "is the wonderful cure which the fungous substance

separating the lobes of the kernel, pulverised and drank in wine in a

moderate quantity, did perform upon the English army in Ireland,

afflicted with a dysentery, when no other remedy could prevail." The

juice of the rind was also used as an effectual gargle for sore throats.

With such a list of healing virtues, real or

supposed, no wonder that the walnut tree has been so extensively

propagated in continental countries; and probably, owing to a belief to

some extent in these reputed qualities, it was first introduced into

this country by the early monks from the continent of Europe; and hence

the earliest specimens now extant are, as we have shown, chiefly to be

found flourishing beside the mouldering ruins of the old ecclesiastical

foundations of their departed hierarchy.

|