|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

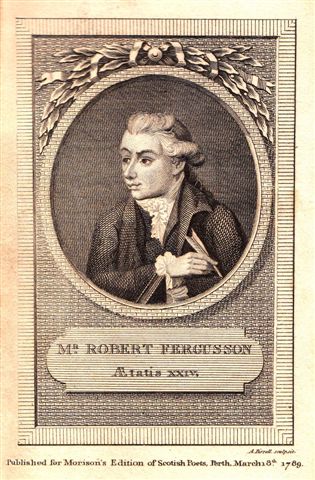

Engraving of Fergusson, from the Perth edition,

1789.

Courtesy of the G. Ross Roy Collection, University of South Carolina

Libraries

It

is an honor to welcome Dr. Rhona Brown for the third time to the pages of

Robert Burns Lives!. Only a handful of writers have contributed two or

more times, and I find it encouraging that scholars like Dr. Brown are

willing to share with our readers their works on Burns or, in this case,

Robert Fergusson who is known by many as “Robert Burns’s favourite Scottish

poet”.

Below you will find an impressive list of some of Dr. Brown’s academic

credits. Word on the street is that she has a new book on Fergusson

scheduled for publication next year entitled Robert Fergusson and the

Scottish Periodical Press. Rhona also has written an essay

for another new book on Burns (Robert Burns in Transatlantic Culture

co-edited by Sharon Alker, Leith Davis, and Holly Faith Nelson) that will be

in print next year. The essay is “Guid black prent: Robert Burns and the

Contemporary Scottish and American Periodical Press.” Both books, which I am

looking forward to reviewing in these pages on Robert Burns, will be

published by Ashgate Press.

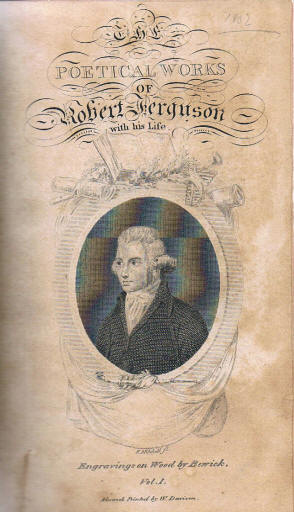

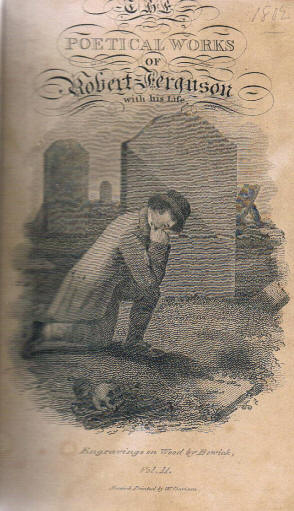

Poetical Works of

Robert Fergusson

[Electric

Scotland Note: We have a pdf file of his works

on the site.]

Rhona Brown is a particular favorite of mine. When Glasgow University

awarded our dear friend Dr. G. Ross Roy an honorary degree, I contacted her

and asked if she would be willing to cover the presentation for the pages of

Robert Burns Lives! and she readily agreed. Later, when the first G.

Ross Roy Medal for Excellence in Post Graduate Study in Scottish Literature

was presented to Dr. Ainsley McIntosh of the University of Aberdeen, I asked

Rhona to again help me out by writing an article about the ceremony. She

came through again for our readers and wrote another impressive article

about Professor Roy, the renowned Burns scholar who has left a trail for all

of us to follow. I will always be indebted to Rhona and her contributions

which we have enjoyed, and I hope you will take time to read them on

http://www.electricscotland.com/familytree/frank/burns.htm,

Chapters 61 and 98.)

Today’s essay, “The Biographical Construction of Robert Fergusson, 1774 –

1900” first appeared in the 2009/10 Winter issue of THE DROUTH. This

unique journal is not just content to have two great co-editors, Mitchell

Miller and Johnny Rodger, but they also invite someone to be guest editor

and Rhona Brown was chosen for this issue. She is indeed a multi-talented

young lady!

Since its inception Robert Burns Lives! has published many wonderful

articles by some very recognizable Burns scholars, but I have never seen an

article such as this one on Robert Fergusson to compliment the Burns

articles. I have always wanted a great piece on Robert Fergusson to grace

our pages and folks, here it is! Please enjoy it as much as I do.

I’m grateful for the editors of THE DROUTH allowing me to come back for the

second week to use another of their articles. I also contacted the talented

Scottish artist Ian McCulloch to ask a very unusual question requesting his

permission to use the journal’s cover for the second week in a row since

Rhona served as Guest Editor. He readily agreed when I explained the

situation to him.

%2070x50cms%20acrylic%20on%20paper.jpg)

"Brothers" by Ian McCulloch on the cover on

THE DROUTH Winter 2009/10

But in fairness to our readers, I asked him for more details on the painting

so as not to include the same information twice on our website. Here is what

Ian shared with me regarding his painting “Brothers”.

“The image is situated in the oriel window space of a small flat I have at

the south end of the island of Bute in the Firth of Clyde. It looks out over

the sea which at night can have a phosphorescent glow. The composition is

largely symmetrical to give a stillness and monumentality to the

composition. The perspective of the table with the trumpet in the foreground

has been altered to lead the eye into the picture.”

More of Ian’s work can be found on the Society of Scottish Artists’ website,

www.s-s-a.org

(click on “Artists”, then “Ian McCulloch” followed by “See Portfolio” and

that will take you to his paintings).

Years ago while wondering around various bookstores in Edinburgh, I visited

with Elizabeth Strong, proprietor of McNaughtan’s Bookshop on Haddington

Place at Leith Walk just down the street from Giulianos, our favourite

Italian restaurant in that city where a delicious bowl of mussels can be

found until the wee hours of the morning. McNaughtan’s became another

favorite place to visit on our trips to Edinburgh and as we explored this

beautiful old shop that day, there sitting on the shelf awaiting our arrival

was The Poetical Works of Robert Fergusson with his Life bound

in beautiful brown leather. Someone had written 1802 on the content pages of

both books. More power to them and how they derived at that date, I’m not

sure but it sounds good to me! I was so happy to find these two volumes that

I hand carried them back to Atlanta, not trusting it to be shipped with

dozens of other books purchased during the visit. Much later, Robert

Crawford’s critical study Heaven-Taught Fergusson, along with Sydney

Goodsir Smith’s Robert Fergusson, 1750-74 helped me to

appreciate these two volumes even more.

Pictures courtesy of the DROUTH

The statue of Fergusson is outside the Canongate

Kirk

Join me now as we read about Robert Fergusson, the man Robert Burns admired.

Burns paid for a tombstone to be placed on Fergusson’s grave and later wrote

these words of tribute to Fergusson:

O

thou, my elder brother in Misfortune

By far my elder Brother in the muse!

(FRS: 12-1-10)

The Biographical Construction of Robert Fergusson, 1774-1900

By Rhona Brown

University of Glasgow

Robert Fergusson died in 1774, in Edinburgh’s ‘Bedlam’

Asylum, aged twenty-four. His life was brief, tragic and easily mythologised.

Biographical interest in the poet Robert Louis Stevenson characterised as

‘the poor, white-faced, drunken, vicious boy, who raved himself to death in

the Edinburgh madhouse’i

has been such that he has become an archetype of tormented literary genius.

Having said this, the first biography of the poet which exceeds a few

paragraphs is David Irving’s ‘Life of Robert Fergusson’ in his Lives of

the Scottish Poets, published in 1799, a full twenty-five years after

Fergusson’s death. This quarter-century delay is relatively unusual; Byron

died in 1824 and by 1830, Thomas Moore had published Letters and Journals

of Lord Byron, with Notices of his Life. Similarly, Robert Burns died in

1796, with James Currie’s first edition of the poet’s life and works

appearing four years later in 1800. In Fergusson’s case, the delay is not

simply due to his relegation to the status of ‘minor’ Scottish poet. While

Robert Crawford rightly bemoans Fergusson’s traditional treatment as

‘Burns’s John the Baptist’,ii

Burns was also responsible for a reawakening of interest in the Edinburgh

poet. After his first visit to the Scottish capital, Burns embarked on a

costly and lengthy enterprise to erect ‘a stone over [Fergusson’s] revered

ashes’ in the Canongate Kirkyard.iii

The indebtedness of Scotland’s national poet to his precursor naturally

reinvigorated Fergusson’s literary reputation.

Although short accounts of Fergusson’s life had

been published before 1799, the influence of the ‘foundational’ biography is

crucial. Arthur Bradley, discussing accounts of Byron’s and Shelley’s lives,

argues that:

Biography is, after all, a serious

business: it is about locating the logic that underpins the minutiae of

life, constructing grand narratives from fragments of evidence, and

re-discovering the meaning of past, random or even meaningless events. The

obvious danger with this approach is that it leads biographers to omit or

neutralise the pieces of evidence they cannot find or that do not fit into

their logical dialectical jigsaws.iv

Fergusson is a particular victim of these ‘dangers’. In his

case, ‘fragments’ of historical evidence and scant ‘fact’ are the

biographer’s materials. Few of the traditional biographical tools are

available for the study and construction of the poet’s life: all original

correspondence has been lost; no poem can be found in manuscript form, save

his drinking songs for Edinburgh’s Cape Club; his name appears infrequently

in historical records, notwithstanding records of his birth and death, a

mention in the matriculation roll of St. Andrews University, the Cape Club’s

Sederunt Book and membership lists, and an appearance in the ‘List of

Persons who took the usual Oaths to Government’ in the years 1751-88,

appearing as, in his role as a legal clerk, a ‘notary publick’. Indeed, in

his 1799 Life of Fergusson, Irving asserts that ‘the collecting of

manuscripts for the following sketch, has been attended with some

difficulty’,v

while William Roughead, writing in 1919, demonstrates the complications

inherent in the study of the poet’s life in his ‘Note on Robert Fergusson’:

The foul fate which attended Fergusson in

life has since inveterately pursued his memory, and few men have been less

fortunate in their biographers.vi

The earliest biographical note on Fergusson is by his friend

and patron, Thomas Ruddiman, in the Weekly Magazine’s obituary of 20

October 1774. Here, Ruddiman emphasises Fergusson’s convivial and poetic

talents, describing him as ‘a genius so lively’, whose ‘talent for

versification in the Scots dialect, has been exceeded by none, – equalled by

few.’vii

This piece, written before the arrival of Burns, remembers Fergusson as a

pivotal figure in the Scots vernacular tradition. Following

Ruddiman’s obituary, and contemporaneous to the publication of Burns’s

Kilmarnock edition, is John Pinkerton’s entry in his Ancient Scottish

Poems (1786). Pinkerton’s first paragraph sets the biographical model:

This young man, tho much inferior to the

next poet, had talents for Scottish poetry far above those of Allan Ramsay;

yet, unhappily, he was not learned in it, for Ramsay’s Evergreen seems to

have been the utmost bound of his study.viii

Because of the verve of Fergusson’s Scots, critics have

traditionally focused on his Scots vernacular work at the expense of his

English language poetry, which is, in turn, often dismissed as artificial

imitation. As Pinkerton asserts, ‘His Scottish poems are spirited; but

sometimes sink into the low humour of Ramsay. His English poems deserve no

praise’ (Pinkerton, cxli). This linguistic bias led to a critical

construction of Fergusson as exclusively capable in the Scots language.

George Douglas, writing in 1919, describes Fergusson’s English work as

‘undistinguished’ and presenting him at his ‘worst’.ix

Sydney Goodsir Smith writes in 1952 that, ‘as in the case of Burns, we can

neglect his English works’,x

while Allan MacLaine describes Fergusson’s English pieces as ‘imitative,

trite, and worthless as literature’.xi

However, Susan Manning, writing in the most recent collection of essays on

the poet’s work, makes the assertion that the traditional critical

insistence on an absolute separation of ‘sterile competence in English and

the ‘discovery’ of a ‘natural’ Scots medium […] is a creation of the

cultural politics of sentiment which has had the […] effect of diminishing

the ambitiousness of the oeuvre’,xii

while F.W. Freeman presents Fergusson’s work in the context of ‘vernacular

classicism’ and ‘classical cultural ideas and values.’xiii

These critical developments allow for an appreciation of Fergusson as a

Scottish poet operating in British and European literary traditions.

Following Pinkerton’s account is Alexander Campbell’s entry

on the poet in his Introduction to the History of Poetry of Scotland,

published in 1798. In his concern with Fergusson’s apparent depravity,

Campbell states that, ‘The delicate frame of our youthful bard, was but ill

calculated for the orgies of the midnight revel, or the joys of the

overflowing bowl.’xiv

Fergusson is portrayed as a childlike, frail victim, unequipped for the

anarchic social life of eighteenth-century Edinburgh. For the first time,

however subtly, he becomes a tragic poetic hero. Recent criticism has railed

against this simplified depiction of the poet. As Manning argues, the tragic

projection of Fergusson’s life is bolstered by the Romantic movement, down

to the period’s portraiture:

Visual representations have had an eerie

tendency to suggest that Fergusson somehow became increasingly like Keats

after his death, with exaggeratedly intense and soulful features

capitalising on the premonition of premature extinction. (Manning, 90)

According to Campbell’s – and Pinkerton’s – portrayals, the poet’s tragic

flaw is his temptation for the ‘midnight revel’; his talent as a ‘humorous

companion’. This convivial hubris leads to his nemesis: his guilt-inspired

religious mania and eventual dreadful demise. These early biographical notes

are primarily concerned with the moral consequences of Fergusson’s life;

their emphasis is on ‘dissipation’. Accordingly, they lay foundations for

controversy and condemnation in subsequent memoirs.

David Irving’s Life of Robert Fergusson, published in 1799, is the

first biography of length and investigation. However, despite its depth, it

has been dismissed by succeeding biographers as overly moralistic on the

poet’s convivial habits. Irving’s piece is, undoubtedly, austere in its

sermon, but, at the same time, it is the first memoir to expose nuances of

Fergusson’s life and work. Irving’s statements on Fergusson’s English

productions cannot be termed sympathetic, but he is careful to note the

‘multifarious’ (Irving, 419) nature of the poet’s corpus:

His works […] are of very unequal merit; some of

them excellent, some even below mediocrity. It is in the composition of his

Scottish poems that we must expect to find his efforts most successful. To

such of his pieces as are written in English very little praise is due –

they occasionally discover marks of genius, but the greater part appear

deficient in every quality which tends to interest and captivate the mind.

(Irving, 430-1)

As

is common, Irving is biased in favour of the poet’s first-rate Scots

vernacular work. Having said this, the biographer acknowledges – albeit

grudgingly – Fergusson’s literary range.

In

the infamous portion of the Life concerned with Fergusson’s

debauchery, Irving intensifies his censorious tone. His description of

Fergusson’s dissoluteness is the basis for irate retorts from later

biographers:

His latter years were wasted in perpetual

dissipation. The condition to which he had reduced himself, prepared him for

grasping at every object which promised a temporary alleviation of his

cares; and as his funds were often in an exhausted state, he at length had

recourse to mean expedients. […] When he contemplated the high hopes from

which he had fallen, his mind was visited by bitter remorse. But the

resolutions of amendment which he formed were always of short duration. He

was soon resubdued by the allurements of vice. (Irving, 432-3)

These statements provide the basis for the dismissal of

Irving’s biographical contribution by subsequent commentators. However,

despite his sermonising, Irving makes illuminating asides which represent

psychological sensitivity to Fergusson’s state of mind shortly before his

death. Irving recognises that the poet’s indulgence may have been the result

of a subconscious need to escape from mental torment; ‘a temporary

alleviation of his cares’. Such psychological acumen barely features in

later biographies except in sentimental guise. Although he criticises

Fergusson’s hedonism, he also recognises that the poet never let his

profession slide: ‘Notwithstanding the miserable state of dissipation into

which he plunged himself, his poetical studies were never truly neglected’

(Irving, 432). John A. Fairley, in his ‘Bibliography of Robert Fergusson’

(1914), still the standard list of early editions and memoirs, accords with

this view, asserting that the poet was equally conscientious in his work as

a copyist: ‘Mr. Ralph Richardson, the present Commissary Clerk, in a note to

the writer says: “Fergusson appears to have entered the Commissary office in

Edinburgh in 1769 and to have left it in the beginning of 1774, a few months

before his death.”’xv

Ensuing biographers discredited Irving’s commentary. However, despite

successors’ fixation with Irving’s charge of profligacy against the poet,

his biography portrays Fergusson as a complex human being of considerable

poetic range: Irving’s poet is, at least, no simplified stereotype capable

only in his own rustic language.

The initial rejoinder to Irving’s memoir is written by the

poet’s nephew, James Inverarity, in his ‘Strictures on Irving’s Life of

Fergusson’, published in The Scots Magazine in 1801. While he applies

‘strictures’ on Irving’s biographical credibility, Inverarity echoes his

predecessor’s terms, reiterating Irving’s concern with the supremacy of

reason over instinct, and complementing his moral stance. Inverarity recalls

Irving’s notion that Fergusson’s foundation should have been

reflective ratiocination, but that it ‘was unfortunately too weak to check

the impulse of the passions’. In his explanation of the poet’s succumbing to

temptation, he reasserts an Irving-like moral authority, stating that his

uncle should have been able to ‘resist’ distracting friendship, or

‘evade’ beguiling ‘pleasure’, had his mind been in its reasonable state.xvi

Inverarity, far from providing ‘strictures’ on Irving’s piece, bolsters his

predecessor’s authority, finding moral strength from cerebral logic and the

rejection of instinct.

Replying directly to Inverarity’s appeal for personal knowledge, Thomas

Sommers, in his Life of Robert Fergusson, Scottish Poet (1803), makes

much of his friendship with the poet. Opening his biography, Sommers

supplies his own opinion of Irving’s memoir:

I agree however with that writer, in many

of his observations, and that it is proper, nay highly commendable, to hold

up to public view, the vices and follies of mankind, in order

to prevent some, and check others, from following a similar

course.xvii

Far from distancing himself from moral significance, Sommers actively

affirms Irving’s didacticism. Sommers is, however, also concerned with

adjusting previous accounts of the poet’s life. Although his statements on

Fergusson’s drinking habits are a direct confutation of Irving’s

censoriousness, his account appears to benefit from personal acquaintance:

I passed many happy hours with him, not in

dissipation and folly, but in useful conversation, and in

listening to the more inviting and rational displays of his wit,

sentiment, and song; in the exercise of which, he never failed to

please, instruct and charm. (Sommers, 46)

In

contrast to Irving’s portrayal of ‘perpetual dissipation’, Sommers provides

a sympathetic portrait of Fergusson’s conviviality, intended to protect his

friend’s memory from charges of ‘folly’. However, Sommers admits that he

finds ‘rational displays’ more ‘inviting’ than those fuelled by alcohol.

Echoing Irving’s theme, Sommers presents Fergusson’s life as a moral lesson,

one which will discourage others from ‘following a similar course’. As a

result, his cheerful but unconvincing description of Fergusson’s

conversation reads like a description of his poetry: the poet, like his

work, never fails to teach and delight.

Simultaneously, Sommers’s account exemplifies emerging literary Romanticism,

a concern particularly visible when he describes Fergusson trying his poetic

talents as a student at St. Andrews University:

About this time his poetical talents were

beginning to appear, and by yielding to their natural impulse, he became

negligent of his academical studies. Every day produced something new, the

offspring of his fertile pen. (Sommers, 11)

Fergusson here becomes a model Romantic poet, his work

characterised by innate urge: unable to control his ‘fertile pen’, his

creative frenzy leads to ‘negligence’ of his university work. In his final

estimation of his friend’s poetic worth, Sommers states that, ‘The

versification is so easy and natural, that it seems to flow spontaneously,

without any kind of effort on the part of the poet’ (Sommers, 41). Both

descriptions of Fergusson’s poetic status demonstrate the influence of the

developing Romantic movement: Sommers’s remarks appear to have been lifted

with embellishment from William Wordsworth’s Preface to the Lyrical

Ballads. Sommers’s description of Fergusson’s muse as a ‘natural

impulse’, as ‘easy and natural’ and ‘flowing spontaneously’ is strongly

reminiscent of the Preface’s statement that ‘all good poetry is the

spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings’.xviii

Simultaneously, Romanticism’s tenets of rusticity, freedom from convention,

spontaneity and use of ‘the real language of men’ (Wordsworth, 595) fit a

simplified estimation of Fergusson’s contribution: he died too young, like

Keats and Byron; he writes in ‘the real language of men’, the Scots

vernacular; he writes instinctively and without revision; he baulks at

convention; he provides a rustic ideal. Accordingly, Manning asserts that,

‘well before Wordsworth’s Preface’ this poetic brand was created, and,

consequently:

We have inherited a Burnsian (and subsequently

Wordsworthian) model of the Romantic poet – in each case a self-construction

designed to obscure the poet’s extensive neoclassical reading and rhetorical

training. (Manning, 92)

While Sommers attempts to liberate Fergusson’s memory from Irving’s stern

moral lesson, his biography is the first to read the poet’s life through a

Romantic lens. As precursor to Burns and Wordsworth, Fergusson’s life is

presented in an alien, but paradoxically all too native, context. For

Sommers, Fergusson’s is a ‘natural impulse’; his writing is instinctive; not

cerebral. His portrayal, however attractive it may be, ‘obscures’

Fergusson’s scholarly erudition.

Adding his portrayal is Hugh Miller who, in his Tales and Sketches

(1869), provides an imaginary account of his protagonist’s friendship with

‘Fergusson’ which draws on previous biographies and his own literary

invention. In his first conversation with Miller’s fictional protagonist,

Mr. Lindsay, ‘Fergusson’ announces his poetic method:

There is poetry in the remote: the bleak

hill seems a darker firmament, and the chill wreath of vapour a river of

fire. […] I seek for poetry among the fields and cottages of my own land.xix

Fergusson, often called the city laureate of Auld Reikie, becomes, for

Miller, the poet of the ‘remote’, while his account of ‘the bleak hill’ and

its poetic inspiration is more reminiscent of Wordsworth than Fergusson.

Miller’s Fergusson is portrayed as a rustic, Romantic bard, finding

inspiration in the sublime aspects of nature. Here too, he becomes a

prototype for Burns, seeking for the poetry of ‘fields and cottages’. As

Wordsworth states in his Preface to the Lyrical Ballads:

Low and rustic life was generally chosen,

because in that condition, the essential passions of the heart find a better

soil in which they can attain their maturity, are less under restraint, and

speak a plainer and more emphatic language; because in that condition of

life our elementary feelings co-exist in a state of greater simplicity, and,

consequently, may be more accurately contemplated, and more forcibly

communicated; […] because in that condition the passions of men are

incorporated with the beautiful and permanent forms of nature. (Wordsworth,

597)

Miller has evidently absorbed his Lyrical Ballads, and as a result,

Fergusson becomes a model Wordsworthian poet, finding inspiration in the

‘beautiful and permanent forms of nature’ exemplified by the ‘bleak hill’.

Moreover, Miller obscures Fergusson’s education by describing it as

‘twofold’; ‘he studied in the schools and among the people, but it was in

the latter tract alone that he required the materials for all his better

poetry’ (Miller, 14). This description reveals a concern with the doctrines

of Romanticism and Scottish myth. Just as Wordsworth recommends that poetry

be rooted in the natural landscape and the ‘real language of men’, so too

does Scottish myth insist on egalitarianism; the belief in Scotland as a

meritocracy was one in which writers of the kailyard school placed pride.

Carl MacDougall encapsulates this myth:

The canonisation of Burns, Wallace, David

Livingstone and others into the broader lad o’ pairts mythology underlined a

wider myth, ‘that Scottish society was inherently democratic and

meritocratic’.xx

In

Miller’s ‘tale’, Fergusson is portrayed as a ‘lad o’ pairts’; a poet ‘of the

[Scottish] people’, thus setting the standard that ‘English’ neoclassicism

is cerebral, artificial and dispensable, while the Scots vernacular is

natural, instinctive and essential.

Alexander Balloch Grosart’s Robert Fergusson (1898) is

a natural successor to Miller’s account. Although Grosart appears to provide

research lacking in previous pieces, critics have expressed distrust of his

study. Alexander Law, in an essay on the Lives of Fergusson, points out that

‘the manuscripts that Grosart consulted have apparently disappeared and we

cannot now check the accuracy of his quotations’, while he wishes for

‘confirmation’ of the whereabouts of a collection of manuscripts which

provide the basis of Grosart’s study.xxi

Furthermore, Stefan Collini offers a worldly explanation for Grosart’s

literary acquisitions when he discusses the Dictionary of National

Biography’s founder, Leslie Stephen’s, tribulations with contributors:

One enemy [Stephen] certainly made was

Alexander Balloch Grosart DD […]. As early as October 1883, Stephen was

complaining that he had ‘had my usual letter of abuse from that old fool

Grosart’, but things took an altogether more serious turn when it was

discovered, very late in the day, that Grosart had not only reproduced,

without acknowledgement, entries he had already published in the

Encyclopaedia Britannica, but had resorted to inventing some of his

sources as well.xxii

It

is with caution, therefore, that one should approach Grosart’s biography. In

addition to his frequent excursions into ‘invention’, Roughead describes

Grosart’s writing style as highly-wrought and opaque: while his piece is a

‘labour of love’, its style is, according to Roughead, ‘irritating’, and its

material ‘mishandled’ (Roughead, 510).

Grosart begins by describing ‘our task of

love, the re-writing of his pathetic story’.xxiii

Emotion is to the fore, as is an appreciation of – and at times a revelling

in – the pathos of Fergusson’s life. Grosart describes Fergusson’s family

situation thus:

Though William and Elizabeth Fergusson’s

children were thus of the Poor, the ‘tenty’ reader […] will have taken note

of an especially Scottish, and especially creditable Scottish,

characteristic, viz. that their parents, out of their little income,

contrived to provide for the early and thorough education of their children,

girls as well as boys. (Grosart, 31)

Fergusson’s parents are applauded for their emphasis on

education for each of their children. However, Grosart simultaneously

constructs Fergusson as the archetypal Scottish ‘lad o’ pairts’: the poet

comes from a poor family to a university education, going on to national

recognition. In fact, the ‘lad o’ pairts’ myth seems to have been a

particular fascination for Grosart. In his Preface to The Works of

Michael Bruce, another ‘delicate’ Scottish poet who died at an early

age, he describes the myth’s importance: ‘A godly parentage weighs down mere

outward splendour […]. The men of Scotland who have made their deepest mark

on their generation, have worked their way upward from just such levels.’xxiv

His description of Fergusson’s education

climaxes in a general truth regarding Scotland’s apparently meritocratic

character:

It has ever been the glory of Scotland that her

humblest peasantry and ‘common people’ – name of honour – equally with the

higher, have valued the John Knox-established Parish schools and ‘ettled’

at something beyond them for their children. (Grosart, 31)

Fergusson is demoted to the level of the ‘humblest peasantry’

and made to fit the Burnsian template of the Presbyterian cotter. Grosart’s

association of ‘Parish Schools’ with Fergusson is misleading: he states that

Fergusson was taught in a ‘private or adventure school’ (Grosart, 38) in

1756, before moving to ‘the royal High School of his native city’ (Grosart,

39) in 1758. The poet then progresses, by aid of a bursary, to the Grammar

School of Dundee around 1762 (Grosart, 44). Fergusson’s education is

consequently dissimilar to Burns’s, which took place in ‘a small school at

Alloway Miln, about a mile from the house in which he was born’, where he

made ‘rapid progress in reading, spelling and writing; they committed psalms

and hymns to memory with extraordinary ease’.xxv

The biographer’s depiction of Fergusson’s early education is evidence of his

compulsion to ‘endorse’ Fergusson’s experience by allusion to that of

‘larger’ figures in Scottish literature and myth.

With appropriate rhetoric, Fergusson’s history

fits the stereotype of the ‘lad o’ pairts’. As Grosart states, through

uncommon abilities, Fergusson is taken from his poverty-stricken home to the

University of St. Andrews with the support of a scholarship for boys by the

surname of Fergusson, going on to make his name as a poet who revitalises

the Scottish vernacular tradition. Grosart’s account creates an approving

account of Fergusson’s life, while constructing a notion of Scotland as

inherently meritocratic. To this end, Grosart begins his biography by

setting Fergusson beside such figures as Wordsworth, Burns, Carlyle and

Stevenson. As Angus Calder asserts:

The strong practical emphasis on […] great

figures […] has been linked with the relatively democratic character of

education in Scotland. The touching notion that the country’s universities

were crammed with the sons of ploughmen and stonemasons, ‘lads o’ pairts’,

released into light and fame by devoted dominies in village schools, does

not bear sceptical examination. But it retains imaginative force, if only

because a ploughman, Robert Burns, showed what intellectual stuff the

Scottish rural proletariat was made of.xxvi

While undoubtedly extolling Fergusson’s achievements, Grosart’s account,

which is part of a series entitled ‘Famous Scots’, justifies the poet’s

‘fame’ by conflating his experience with that of Scotland’s national poet.

Grosart’s account of Fergusson’s life is also

touched by his fascination with the Scottish mother figure, providing

numerous miniature portraits of Fergusson’s mother, Elizabeth:

Fergusson’s mother was so out-and-out a

sagacious woman, as well as devout – as was Agnes Brown, mother of the

greater Robert – that we may assume that her ebullient and impulsive

‘laddie’ received many a grave counsel and heard many a fervent prayer in

his behalf. After the Scottish reticent manner, the whole family would be

quietly proud of their Robert’s going to Colledge. (Grosart, 49-50)

Fergusson’s mother becomes a stereotypical Kailyard

matriarch, poor but devout, worrying but righteous, and reserved but proud;

she is, for Grosart, a prototype of Agnes Broun, ‘mother of the greater

Robert’. This interest is an enduring feature of Grosart’s biographical

endeavour. Not only is Elizabeth Fergusson compared to Agnes Broun, but also

to ‘Robert Nicoll’s brave-hearted mother’; ‘she was of a ‘proud spirit’ in a

good sense, and struggled on without complaining or fretting’ (Grosart, 66):

Fergusson’s mother is a patriotic ideal; she is the suffering but staunch

Caledonia. This fixation appears throughout Grosart’s corpus, most notably

in his account of Michael Bruce’s mother in his Preface to Bruce’s Works.

Anne Bruce is, like Fergusson’s, Burns’s and Nicoll’s mothers, a genuine

‘“mother in Israel”, vigilant, loving, frugal, “eident”; […] she

mellowed beautifully as she wore her crown of silver hairs, and exemplified

the “hoary head found in the way of righteousness”’.xxvii

When describing Fergusson’s years at St. Andrews University, Grosart

directly refutes Irving’s censoriousness:

Once more, how wooden, how utterly without least

sense or understanding of humour, your ‘moralisers’ who magnify this

ebullience of waggery into ‘a grave moral offence’! Fiddlesticks, ‘most

reverend doctors!’ (Grosart, 58)

Irving’s moralising is dismissed with an extravagant flourish of sympathy.

Grosart’s emotional approach is further illustrated in his depiction of an

incident in which Fergusson’s uncle, John Forbes, dismissed the poet from

his house and deprived him of work. A minor aspect of the accounts of Irving

and Sommers, the incident becomes, in Grosart’s piece, a pivotal event:

This visit, I reiterate, I regard as the

most fundamental factor in Robert Fergusson’s career. […] As we shall learn

sorrowfully, even when tragedy fell, the poor mother was so abjectly poor

that she had no choice but to allow her ‘child of genius’ to be removed to

the pauper-Bedlam! It thus lies on the surface that John Forbes continued to

the bitter end unbrotherly, penurious, and callous; and that his sister was

of the true old-fashioned Scottish independent spirit and disdained to make

further appeal. (Grosart, 69-70)

Grosart’s stout sense of Christian decency and Victorian charity are

contradicted by the character of Forbes, and this biographical anecdote

becomes, in Grosart’s depiction, a struggle between the respectable

innocence of Fergusson and his mother, and the capitalist-tainted evil of

the poet’s uncle. In his study of the biographies of Byron and Shelley,

Bradley uncovers a similar simplification of opposing forces in the poets’

lives. According to Bradley, Byron and Shelley are depicted in biographies

as polar opposites for various reasons:

The apparently biographical decision to

depict the two poets as contradictory is […] based on more or less

philosophical assumptions. This leaves many biographical studies in the

perilous position of depending on imported philosophical accounts of

difference like Hegelian dialectic which have nothing to do with biography

and operate quite irrespectively of the lives and works of their subjects.

(Bradley, 157)

In

Grosart’s portrayal, the poet’s expulsion from his uncle’s house becomes ‘the

most fundamental factor in Robert Fergusson’s career’ while each of the

myths lauded by Grosart are offended by Forbes and his uncharitable

behaviour. Whereas Fergusson and his family represent the suffering but

honest poor of Scotland; the egalitarian, ‘lad o’ pairts’ ideal, Forbes is

stained by money because he is a farming factor – indeed, Grosart describes

him as a land agent in the mould of Caesar’s master in Burns’s ‘The Twa

Dogs. A Tale’. Through this Hegelian dialectic, the characters in Grosart’s

biography are, arguably, archetypal figures who appeal to a charitable

Victorian mindset with its belief in social progress.

Even at the height of his fame, Grosart’s Fergusson remains the modest ‘lad

o’ pairts’, aware of his humble roots and suspicious of commendations:

Throughout Robert Fergusson kept his head. To

this end, as in the beginning, he remained self-respecting, but modest and

shy to awkwardness when praised. […] He was always uneasy and restless when

his own productions were being praised, but would listen and join the

praises of others cordially. […] ‘Mr. Robert’ (it was always Mr. Robert)

‘was a dear, gentle, modest creature; his cheeks, naturally pale, would

flush with girlish pink at a compliment.’ Surely all this is very fine? (Grosart,

99-100)

Remaining wary of praise, he is ‘self-respecting’. Just as this depiction of

Fergusson successfully presents the poet as a Scottish myth made flesh,

Grosart, the practising Church of Scotland minister, is also immersed in

theology. As Iain Finlayson considers, concepts of Scottish ‘reticence’ are

based on the teachings of Presbyterianism. Just as Fergusson is given

saintly elevation in Grosart’s biography, so is he given bolstered chances

in the afterlife as reward for his ‘tholing’ of his worldly circumstances:

Many a man might make a fortune, but to do

so might imperil his eternal soul: heaven was the final reckoning in which,

if the Magnificat were to be believed, the mighty would be humbled and the

deserving poor elevated to their proper rank which the base world had

unaccountably failed to recognise. Poverty, well-manneredly and stoically

endured, was a passport to good standing in eternity.xxviii

In

his careful depiction of Fergusson as a ‘stoic’, ‘well-mannered’ member of

the ‘deserving poor’, Grosart arguably endeavours to ensure the poet’s ‘good

standing in eternity’. After Irving’s unflinching portrait of Fergusson’s

debauchery, Grosart perhaps attempts to save the poet’s soul from damnation.

Finlayson’s logic further clarifies Grosart’s wrath towards Forbes: just as

Grosart is sure of Fergusson’s ‘elevation’, his faith allows him to attack

Forbes’s ‘callousness’; Forbes, as one of the uncharitable ‘mighty’ is sure

to be ‘humbled’ in the Presbyterian afterlife. Through a consistent

portrayal of Fergusson and his family as blessed, honest but poor

stereotypes, Grosart saves the poet from the eternal punishment that

Irving’s accusations of immorality would ensure.

Fergusson has been put to numerous biographical

uses since his death in 1774. Before the advent of Burns, Ruddiman portrayed

Fergusson as the saviour of a dying Scots vernacular tradition. After the

publication of Burns’s Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect in

1786, Fergusson’s contribution was celebrated and compromised; Burns’s

genuine tributes to his predecessor allowed re-examination, but cemented his

place as literary precursor. Biographies of Fergusson in the late eighteenth

and early nineteenth illuminate the priorities of their particular contexts,

while providing valuable insight into the ways in which Fergusson’s literary

contribution has been understood and valued in divergent periods. What each

biography shares, however, is an appreciation of Fergusson as a literary

artist. Ruddiman’s obituary describes him as a poetic ‘genius’, while

Grosart encapsulates his contribution thus:

He is to be gratefully remembered for what his

vernacular poems did for Robert Burns; for what he did in the nick of time

in asserting the worth and dignity and potentiality of his and our

mother-tongue; for his naturalness, directness, veracity, simplicity,

raciness, humour, sweetness, melody; for his felicitous packing into lines

and couplets sound common sense; for his penetrative perception that man and

not ‘braid claith’ or wealth is ‘the man for a’ that’; for his patriotic

love of country and civil and religious freedom; and for the perfectness –

with only superficial scratches rather than material flaws – of at least

thirteen of his vernacular poems, and for sustaining the proud tradition and

continuity of Scottish song. (Grosart, 159)

While compromised by censoriousness and scarce documentary

evidence, the biographies of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

nevertheless laid the foundation for twentieth- and twenty-first-century

criticism of Fergusson’s work, allowing Matthew P. McDiarmid to publish an

authoritative edition of his life and works in 1954-56, and F.W. Freeman to

describe Fergusson as ‘a highly literate, educated and urbane young

Edinburgh poet’ in 1984.xxix

Only one biography of Fergusson was produced in the twentieth century; W.E.

Gillis’s Auld Reikie’s Laureate: Robert Fergusson, a Critical Biography

sadly remains unpublished.xxx

The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are a golden age of Fergusson

biography. In their engagement with Fergusson’s flaws, triumphs and

circumstances, these memoirs facilitate a nuanced understanding of ‘Robert

Fergusson’ over the last 235 years, but, by extension, a valuable insight

into the creation of a Scottish literary canon.

i

Robert Louis Stevenson, quoted in Alexander Balloch Grosart, Robert

Fergusson (Edinburgh, 1898), 15.

ii

Robert Crawford, ‘Introduction’ to ‘Heaven-Taught Fergusson’: Robert

Burns’s Favourite Scottish Poet (East Linton, 2003), 2.

iii

Robert Burns, Letter to the Honourable Bailies of the Canongate,

Edinburgh, 6 February 1787, in J. De Lancey Ferguson and G. Ross Roy

(eds.), The Letters of Robert Burns (Oxford, 1985), Vol. I., 90.

iv

Arthur Bradley, ‘‘Winging itself with laughter’: Byron and Shelley after

Deconstruction’ in Arthur Bradley and Alan Rawes (eds.), Romantic

Biography (Aldershot, 2003), 152.

v

David Irving, Lives of the Scottish Poets (Glasgow, 1799), 6.

vi

William Roughead, The Riddle of the Ruthvens and Other Studies

(Edinburgh, 1919), 488.

vii

See The Weekly Magazine or Edinburgh Amusement, 20 October 1774,

Vol. XXVI, 128 and Robert Fergusson, Poems on Various Subjects

(Edinburgh, 1799).

viii

John Pinkerton, Pinkerton’s Ancient Scottish Poems (Edinburgh,

1786), cxl-cxli.

ix

George Douglas, Scottish Poetry (Glasgow, 1911), 160.

x

Sydney Goodsir Smith, Robert Fergusson (Edinburgh, 1952), 13.

xi

Allan MacLaine, Robert Fergusson (New York, 1965), 22.

xii

Susan Manning, ‘Robert Fergusson and Eighteenth-Century Poetry’ in

Robert Crawford (ed.), ‘Heaven-Taught Fergusson’: Robert Burns’s

Favourite Scottish Poet (East Linton, 2002), 88.

xiii F.W. Freeman, ‘Robert Fergusson: Pastoral and Politics at Mid

Century’ in Andrew Hook (ed.), The History of Scottish Literature,

Vol. II (Aberdeen, 1987), 141.

xiv

Alexander Campbell, An Introduction to the History of Poetry in

Scotland (Edinburgh, 1798), 292.

xv

John A. Fairley, ‘A Bibliography of Robert Fergusson’ in Records of

the Glasgow Bibliographic Society, Vol. III, Session 1913-15

(Glasgow, 1915), 116. Fairley’s piece is still the standard bibliography

of Fergusson’s work.

xvi

James Inverarity, ‘Strictures on Irving’s Life of Fergusson’ in The

Scots Magazine, Vol. 63, October 1801, 763.

xvii Thomas Sommers, The Life of Robert Fergusson, Scottish Poet

(Edinburgh, 1803), 3.

xviii William Wordsworth, ‘Preface to the Lyrical Ballads’ in

Stephen Gill (ed.), The Oxford Authors William Wordsworth

(Oxford, 1984), 598.

xix

Hugh Miller, ‘Recollections of Ferguson’ in Tales and Sketches

(Edinburgh, 1869), 6-7.

xx

Carl MacDougall, Painting the Forth Bridge: A Search for Scottish

Identity (London, 2001), 8-9.

xxi

Alexander Law, ‘The Bibliography of Robert Fergusson’ in Sydney Goodsir

Smith (ed.), Robert Fergusson, 168-69.

xxii Stefan Collini, ‘Our Island Story’ in London Review of Books,

2005, 3.

xxiii Alexander B. Grosart, Robert Fergusson (Edinburgh,

1898), 8.

xxiv Alexander B. Grosart (ed.), The Works of Michael Bruce

(Edinburgh, 1865), 6-7.

xxv

J.G. Lockhart, The Life of Robert Burns (1828; rpt. London,

1947), 4-5.

xxvi Angus Calder, Revolving Culture: Notes from the Scottish

Republic (London, 1994), 24.

xxvii Grosart, The Works of Michael Bruce, 6.

xxviii Iain Finlayson, The Scots (London, 1987), 71.

xxix F.W. Freeman, Robert Fergusson and the Scots Humanist

Compromise (Edinburgh, 1984), vii.

xxx

W.E. Gillis, Auld Reikie’s Laureate: Robert Fergusson, a Critical

Biography (Edinburgh University PhD thesis, 1955).

UNIVERSITY of GLASGOW

Rhona Brown BA, PhD

Lecturer

-

Eighteenth-century Scottish literature

-

Seventeenth-century Scottish literature

-

Medieval Scottish literature

-

Robert Fergusson

-

Robert Burns

-

Robert Henryson and William Dunbar

-

Traditions of Scottish literature

-

The Scottish Periodical Press

-

Scottish Literature Level 2 Convener

-

Undergraduate Adviser of Studies

-

Scottish Literature Honours progress committee member

-

Departmental Library Representative

-

Departmental Web Co-ordinator

-

Member of SESLL ROC-IT committee

-

Member of SESLL TLQAC committee

Room 405, 7 University

Gardens

Telephone: 0141 330 8529

E-mail:

R.Brown@scotlit.arts.gla.ac.uk

Biography

Rhona Brown graduated from

Strathclyde University in 2000 with a Bachelor of Arts in English,

winning the department’s Meston Prize. In the same year, she began her

PhD in the department of Scottish Literature at the University of

Glasgow, which was entitled, “ For what use

was I made, I wonder?”: The Construction and Revision of Robert

Fergusson in his Cultural Context. During

her doctoral studies, she co-organised two conferences: the University

of Glasgow Graduate School Conference in 2003, entitled ‘Trailblazing’,

and the inaugural Department of Scottish Literature Postgraduate

Conference, ‘Whaur Extremes Meet’, in 2003-04. In 2004, Rhona provided

biographies and commentaries on the work of Robert Henryson, William

Dunbar, Allan Ramsay, Robert Fergusson and Robert Burns for the BBC

website accompanying Carl MacDougall’s BBC2 series,

Writing Scotland (http://www.bbc.co.uk/writingscotland).

After graduating with her

doctorate in 2004, Rhona worked as a teaching assistant in the

departments of Scottish Literature and English Language in the

University of Glasgow, as well as in the department of English

Literature at the University of Edinburgh. She also worked as Production

Editor for Rodopi’s SCROLL (Scottish Cultural Review of Literature and

Language) series, and completed a British Academy-funded research

project on the unpublished correspondence of Robert Burns’s first

biographer, James Currie, which is published online at

http://www.gla.ac.uk/departments/scottishliterature/research/researchprojects/curriedatabase/.

In 2005, she was invited to speak on her research on Currie’s letters at

the International Burns Conference at the Mitchell Library. In 2005, she

presented a paper on Robert Fergusson and the Romantic myth at the

British Association for Romantic Studies’ conference in

Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and in 2006 she spoke on the reception of Robert

Burns in the Scottish and American periodical press at the ‘Scottish

Romanticism and World Literatures’ conference which was held in

Berkeley, California. In 2007, she presented papers on the abolitionist

poetry of James Currie and William Roscoe at the B.A.R.S. conference at

Bristol University and at the ‘Liverpool: A Sense of Time and Place’

conference, held in celebration of the city’s 800th anniversary. Rhona

was a member of the organising committee for the ‘Robert Burns 1759 to

2009’ conference, a major symposium run by the newly inaugurated Centre

for Robert Burns Studies to mark the 250th anniversary of the poet’s

birth. In 2009, she was invited to speak at the ‘Robert Burns in

European Culture’ conference in Prague, the 'Transatlantic Burns'

conference at Vancouver, and at the ‘Robert Burns and the Poets’

conference, held at Oxford University.

Rhona joined the department

as lecturer in 2006. In 2007, she was made a General Editor on Rodopi’s

SCROLL series, and in 2008 became Reviews Editor for

Scottish Literary Review.

She is currently preparing a monograph on the eighteenth-century

Edinburgh poet, Robert Fergusson, and has published articles on James

Currie, John Mitchell, James Hogg, Robert Hogg, Thomas Chatterton,

Laurence Sterne, James Tytler and Robert Burns. Rhona’s current

research interests include the eighteenth-century newspapers, the

Edinburgh periodical press and Robert Burns.

7 University Gardens,

University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, Scotland, UK

tel: +44 (0)141 330 5093

fax: +44 (0)141 330 2431

email:

enquiries@scotlit.arts.gla.ac.uk

|