|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

The following article by

Professor Christopher Whatley appeared in the January 2011 issue of the

BBC History Magazine.

Professor Whatley is

Professor of Scottish History, a distinguished and active historian who has

risen through the ranks since joining the University of Dundee in 1979 as

lecturer. His most recent book, The Scots and the Union (Edinburgh

2006), a seminal study launched to coincide with the 300th

anniversary of the Union of the Parliaments, met with critical acclaim and

was described as essential reading for anyone who wants to understand the

making of modern Scotland.

Under his headship History

(5 rated) at the University rose to be recognized as among the best in the

country.

A graduate of the University

of Strathclyde, where he also took his PhD, Professor Whatley has published

considerably, including authorship of six substantial books, editorship of

nine books and approximately 60 other works. He has been an external

examiner for programs in Scotland and the European Union and is a member of

Peer Review College of the Arts & Humanities Research Council and the Royal

Society of Edinburgh of which he is also a member of the Council. He is in

frequent demand by TV, radio and print media as consultant, presenter and

contributor. He is also a founder director and chair of the editorial board

of Dundee University Press.

Thanks to Professor Whatley

for his courtesies in sharing this article with our readers. We also

appreciate the support of Aileen Ross for her added assistance.

(FRS: 5-9-2012)

Robert Burns

Patrician Protégé, People’s Poet

Professor Christopher

Whatley

On a grey, sleet-spattered

Thursday in 1877, a vast crowd comprising an estimated 100,000 people

crushed into Glasgow’s George Square. Others watched from windows and even

rooftops, while in the surrounding streets thousands more strained to catch

at least part of the proceedings. The occasion, which had been preceded by a

colorful procession of the city’s trades, accompanied by the cacophonous

sounds of 30 or so bands struggling to play the same tune at the same time,

was the unveiling of a statue of Robert Burns, Scotland’s national poet. The

day chosen was 25 January, the date of Burns’s birthday, in 1759.

The scale and extent of

public participation surrounding the Glasgow unveiling ceremony were neither

unusual nor unprecedented. Much earlier, in 1796, Burns’s death had induced

the kind of emotional reaction we associate nowadays with the deaths of

celebrities – President JF Kennedy, Princess Diana or most recently Michael

Jackson. ”Great was the grief of the people for their poet’s death,” wrote

one of Burns’s contemporaries. “They felt they had lost their greatest man.”

Dumfries, where Burns spent

the last years of his life as an excise officer, and where he died, was

“besieged” for his funeral. It was again for the funeral of his wife, Jean

Armour, almost 40 years later. Collections of Burns’s works poured from the

presses. There was a deepening hunger for biographical details of his life.

Apparent too was a morbid but intense and widespread interest in Burns’s

mortal but now immortalized remains, including from phrenologists who

examined his skull.

Pilgrims flocked to places

associated with Burns and his poems and songs. Relic hunters stripped bare

the timbers of the ruins of Alloway Kirk, scene of one of Burns’s best-known

poems, Tam O’ Shanter. Dumfries, where Burns’s mausoleum in St

Michael’s churchyard was located, became Scotland’s Jerusalem. Over time

entire industries emerged to satisfy the demands of Burns-lovers for busts,

statuettes, engravings, snuffboxes and a multitude of other Burns ephemera.

Memorials and statues abounded, principally in Scotland, but several were

erected in Canada and the United States, Australia and New Zealand.

Just how massive the Burns

phenomenon was became clear in August 1844 at the first ever Burns Festival

– held in Ayr, within sight of his birthplace. Estimates of the numbers

present ranged from 50,000 to 80,000. The unprecedented level of

participation attracted nationwide interest, not least on the part of London

journalists and others who sought to understand why a Scottish poet should

have aroused such fervour on the part of those present.

Behind the festival, as with

the memorials that had been built in Burns’s memory prior to 1844, were

representatives of Scotland’s older ruling class. Along with the arch-Tory

academic, Edinburgh University’s Professor John Wilson, Scotland’s emergent

commercial and manufacturing elite also played a leading role, including Sir

Archibald Alison, Glasgow’s sheriff and scourge of working-class radicalism.

The motives that lay behind such patrician promotion of Burns were mixed.

Guilt was one; they had allowed the poet to die in poverty. As important

however was Scottish patriotism. The festival organizers recognized that

Burns, much of whose work was written in Scots, had been instrumental in

preserving the Scottish language and dialect.

This they saw as the essence

of Scottish identity – under threat in the united British kingdom. In this

respect Burns appealed across party lines as well as class boundaries, and

he united lowland Scotland – even if there were clergymen who deplored the

elevation to secular sainthood of a poet who had celebrated drink – fuelled

excess and mocked the Kirk.

Central to the Ayr festival

project however was the presentation of Burns as the epitome of

pre-industrialised Scottish society in which pious peasants knew their place

and stoically accepted their lot. The festival’s organizers employed as

their manifesto for this ideal world Burns’s poem, The Cotter’s Saturday

Night, which could be read as a recipe for personal, familial and social

contentment. Scottish conservatives were anxious not only to preserve such

characteristics, but also to promote them as a bastion against the forces of

industrialisation, urbanisation and revolution.

Yet what was also apparent

to observers in 1844 was that the ordinary people present – tradesmen,

ploughmen and shepherds predominated – had their own views about Burns. What

inspired them were lyrics like “A man’s a man”, the tune to which they had

chosen to march in the procession that preceded the festival. That Burns was

more popular than Sir Walter Scott among Scottish artisans, concluded one

group of interested spectators, was due to the fact that Burns had been a

sinner but also that he was a democrat, something that the organizers were

at pains to ignore or even deny.

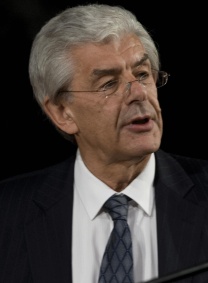

Professor Christopher

Whatley in July 2008

Ironically, even within

The Cotter’s Saturday Night were lines and potentially corrosive

sentiments they were unable to censure, including the following:

Princes and lords are but

the breath of kings,

‘An honest man’s the noble work of GOD:’

And certes, in fair Virtue’s heavenly road,

The Cottage leaves the Palace far behind:

What is a lordling’s pomp? A cumbrous load,

Disguising oft the wretch of human kind,

Studied in the arts of Hell,’ in wickedness refin’d!

Radical attacks on the

festival began almost as soon as it was over. Do not feast upon your poet’s

grave, “Having first starved him into it”, thundered Feargus O’Connor in the

Chartist Northern Star. The charge echoed the comments of a Chartist

lecturer who had visited the Burns monument in Alloway the previous year. He

acknowledged that it was a fine structure, a fitting “shrine to genius”. Yet

it did not reflect well on the class that had erected it: whoever recalls

Burns’s death-bed appeal for five pounds, he wrote, will regard “this cold

stone pile as a monument to the meanness as well as pride, of the Scottish

aristocracy.

Burns’s appeal to the

respectable working classes in Scotland was multifaceted. His poetry

captured what for many was a familiar if rapidly disappearing rural way of

life; he ignited the smoldering embers of Scottish national consciousness.

As someone who had self-consciously portrayed himself as a “heaven taught”

ploughman, Burns offered hope for ordinary people that they could rise above

the circumstances of their birth.

Indeed Burns inspired a

small army of British worker-bards. Resonating even more strongly was his

egalitarianism. Many thousands of working people contributed their single

shilling to the Glasgow Burns statue fund. In Dundee too, workers subscribed

to the cost of the Burns statue unveiled in October 1880.

Resounding cheers from what

had been the largest crowd in this jute manufacturing town’s history were

heard when the main speaker on the occasion, Frank Henderson MP, pronounced

that by showing “the nobility of the soul was confined to no rank”, and that

the “honest man was the noblest work of God”, Burns had transformed the

lives of Scottish workers. But Burns’s capacity to inspire was not confined

to Scotland. His influence was felt among weaver communities in Ulster from

the 1790s, and Burns was adopted as the poet of the early American republic.

Indeed, Abraham Lincoln was among his most ardent readers and admirers,

frequently quoting lines from his poetry.

Burns suppers, the first of

which was held in 1801, are now ubiquitous, with perhaps nine million

attending them worldwide as recently as January 2009. The Burns being

celebrated will differ widely from place to place. What will unite those

present will be the consumption of “mountains of haggis”, (too) much whisky,

and spirited renditions of his poems and songs – ending with Auld Lang

Syne.

The best of them will

acknowledge Robert Burns’s importance in promoting – in simple but

unforgettable language – ideas and aspirations that lifted the spirits of

countless thousands of ordinary people in the long march towards democracy. |