|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

Back in 1954 I found myself

living with my sister Peggy in what was then known as Charleston Heights, a

vast suburb just north of Charleston, SC. To “go downtown” meant going to

King Street. My high school buddies sometimes called our charming town the

“City by the Bay”, long before Tony Bennett “left his heart in San

Francisco”. Charleston prided itself on being “America’s Most Historic City”

and, as you came down the second span at the foot of that mighty Cooper

River Bridge, a huge sign said so. After all, what was printed in The

News and Courier or what the city fathers erected on signs was

the law, if not the truth, at least for anyone from Charleston. The city is

flanked on one side by the Cooper River and on the other by the Ashley

River, and the Atlantic Ocean was formed when these two rivers merged. We

had highbrows in the city and they were known, then and now, as SOBs because

they lived South of Broad.

When a hurricane dared come

close to the city, school would be dismissed and some of us would make our

way to The Battery to see the waves splashing as high as thirty feet. You

didn’t hang around there long, but you could brag when school reopened that

you had been there for the great water show. I played (very little)

football, basketball, and baseball at North Charleston High School, famous

for the words written over the entryway, “EDUCATION IS A POSSESSION OF WHICH

MAN CANNOT BE ROBBED”. Mostly, however, I pumped gas at Mr. Hull’s Esso

service station for a dollar an hour after school and on weekends. Back

then a dollar would buy you 3.3 gallons of gas! I learned my first business

lessons from that fine old man and still use most of them today.

I write this to let you know

what a special place Charleston is for me. I was thrilled to learn from this

week’s article by Patrick Scott that Gavin Turnbull, one of Robert Burns’

friends, had emigrated from Scotland to Charleston. Many historians and

Burns scholars had missed this fact for years. I have walked various streets

that Burns walked in Scotland but never thought too much about his friend

Turnbull who ventured away from the auld country to my neck of the woods.

This is new material, as fresh as any you will find. Patrick’s article is a

fun and exciting one and well worth reading. This is the latest ground to be

broken on a Burns contemporary in, of all places, Charleston, South

Carolina. I tip my hat to Patrick Scott! (FRS: 11.28.12)

Whatever Happened to Gavin

Turnbull?

Hunting Down a Friend of Burns in South Carolina

by Patrick

Scott

It sometimes seems as if

there is nothing new to be discovered about Robert Burns or his

contemporaries. The sheer bulk of over two hundred years of Burnsian

scholarship, the long shelves of the Burns Chronicle, the thousands

of volumes in the Roy Collection and the Mitchell Library and elsewhere—all

warn us that there is much more material already in print than any of us can

really get a grip on. Surely, one feels, everything worth knowing has

already been found by someone, if only we knew where it was published.

But over the past few weeks,

I’ve come on “new” information about one of Burns’s Ayrshire friends and

near-contemporaries, Gavin Turnbull—new facts about his subsequent life as

an actor and new poems included in neither of his published collections. It

wasn’t initially my discovery. The crucial link was made several years ago

by David Radcliffe of Virginia Tech, who first identified where Turnbull

went after he left Scotland. However almost none of the information on

Turnbull’s later life summarized below seems to be known in the mainstream

Burns resources. I haven’t finished the research, but I want to share some

of what I have found, and tell where the hunt has taken me so far.

Turnbull and his earlier

life are of course mentioned in many of the sources on Burns’s Ayrshire.

Paterson’s The Contemporaries of Burns (1840) paints a sympathetic

portrait of Turnbull’s impoverished youth working for a Kilmarnock

carpet-manufacturer and of his commitment to poetry:

“He resided alone in a small

garret,” says our informant, “in which there was no furniture. The bed on

which he lay was entirely composed of straw, ... with the exception of an

old patched covering which he threw over himself at night. He had no chair

to sit upon. A cold stone placed by the fire; and the sole of a small window

at one end of the room was all he had for a table, from which to take his

food, or on which to write his verses” (Paterson, p. 93).

Despite these handicaps,

Turnbull published a quite substantial first volume, Poetical Essays

(Glasgow, 1788), followed by a slimmer and even rarer second volume Poems

(Dumfries, 1794). As Professor Carruthers has recently commented, much of

his poetry is high-flown and rather derivative, but not all, and it deserves

fuller consideration. Here’s the impoverished Turnbull in mock-supplication

to a local tailor, whom he wants to make him a new suit in exchange for the

remnants of the cloth;

A poet, tatter’d and

forlorn,

Whase coat and breeks are sadly torn,

Wha lately sue’d for aid divine,

Now, Taylor, maun apply for thine; ...

A ragged Bard, however gabby,

Will ay be counted dull and shabby; ...

And here’s Turnbull writing

to Burns’s friend David Sillar, describing his poverty and loneliness (“I

sit beside the chimla lug,/ And spin awa my rhyme”), complaining that “Noble

Patrons” favour dullards whilst neglecting “chiels of maist ingine and

skill,” but then going on to relish life anyway:

Then heed na, Davie,

tho’ we be

A race expos’d to misery,

A’ mankind hae their skair;

Yet, wi’ the few whase hearts are fir’d

Wi’ love o’ sang, by Him inspir’d,

What mortals can compare.

Burns mentions Turnbull in

three letters, two trying to send Turnbull money for six copies of the 1788

edition that Burns had been selling on Turnbull’s behalf (Letters I:

399, 413-414), and one from Dumfries in 1793 trying to interest George

Thomson in three of Turnbull’s songs for his Select Collection (Letters

II: 256-258).

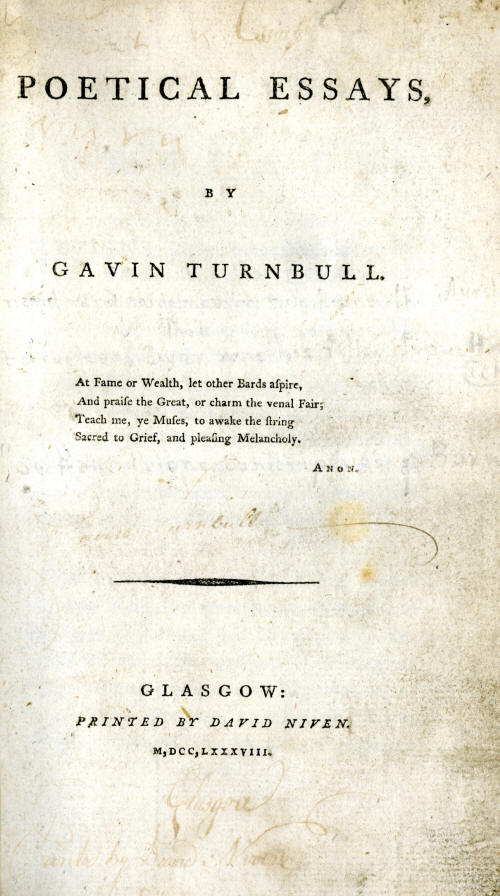

Title-page from Gavin

Turnbull’s first book

(G. Ross

Roy Collection)

But despite his compelling

story, the Burnsian sources on Turnbull offer little clue about his

subsequent career. He had moved to Dumfries to work in the new theatre, and

married an actress there, but the earliest source, Alexander Campbell’s

Introduction to the History of Poetry in Scotland (1798), gives no

information even about Turnbull’s life in Dumfries. Thomas Crichton, in the

Weaver’s Magazine (Paisley, 1819), says simply “I have been informed

that like his friend [Alexander] Wilson, he afterwards went to America”

(Paterson, Appendix, p. 24). Paterson himself admits that “Of the subsequent

history of Turnbull we are almost entirely ignorant” (p. 110), concluding

“It is said he afterwards emigrated to America; and there is every

probability that he died there” (p. 112). Maurice Lindsay similarly throws

up his hands: “Turnbull married an actress, and with her emigrated to

America, where all trace of them has been lost” (p. 364). None of the

Burnsian sources risks supplying dates for Turnbull’s birth or death.

What got me past this logjam

was Professor Radcliffe’s research into Turnbull’s usually-neglected

non-Scots poems, which show the influence of the English Renaissance poet

Edmund Spenser. Turnbull wasn’t the only Scottish poet to be so

influenced—others include James Thomson in his Castle of Indolence

(1748) and James Beattie in The Minstrel (1771-1774). Radcliffe’s

remarkable web-site, Spenser and the Tradition: English Poetry 1579-1830,

reproduces several of Turnbull’s Spenserian poems, and notes that they were

reprinted in various American newspapers, including ones published in

Charleston, South Carolina. In annotating the poems, and in his entry about

Turnbull for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (as updated

on the web, though available there only by subscription), Prof. Radcliffe

provides, I think for the first time, such basic information as Turnbull’s

dates (ca. 1765-1816), based on an obituary referenced to a Massachusetts

newspaper. Turnbull emigrated to the States, he notes, “certainly before

1798,” and “by 1799 he had settled in Charleston” (ODNB).

I started by looking out the

books on Charleston theatre history, which confirmed Turnbull’s acting

career there, and then went across campus to the South Caroliniana Library,

where Frtiz Hamer, head of published materials, put me on to an index of

immigrants who took U.S. citizenship (Hemperley, p. 225). The original

federal documentation was destroyed many years ago, but at the South

Carolina Department of Archives and History, out on I-77, with the help of

one of the archivists Steven Tuttle and an old friend Dr. Charles Lesser, I

was able to get fuller information from a nineteenth-century summary on

microfilm (cf. also Holcomb, p. 34). Gavin Turnbull was admitted to

citizenship in Charleston, SC, on October 23, 1813. His age is given as 48,

making his birth date 1765, and so confirming the birthdate given by Prof

Radcliffe, but his place of birth is given as “Berwickshire, NB” (i.e. North

Britain), not as previously suggested in Hawick (which is in Roxburghshire).

At that time, in 1813, he was resident in Charleston, and listed his

occupation as “teacher.”

Back at the South

Caroliniana library, Mr. Hamer put me on to the early Charleston street

directories, which located Turnbull as living in 1806 and 1809 at 21 Mazyck

Street and in 1813 at 96 Tradd Street (though since the early

nineteenth-century house numbering on Charleston streets has often

changed). The following week, I was driving down to Charleston on other

business and was able to go by the City Archives in the new Charleston

County Public Library. There, the city archivist Dr. Nicholas Butler and his

colleagues steered me through further sources on the Charleston theatre,

including the information on theatre buildings in Dr. Butler’s book about

Charleston music, Votaries of Apollo (2007). I looked at some of the

Charleston newspapers there, and then at more when I got back to Columbia,

following up with further books on American theatre history, and the bits of

the jigsaw began to fall into place. Far from Turnbull being lost without

trace, we can often trace what he was doing, and where, night by night,

because he was an actor and newspaper advertisements tell us what role he

was playing in each performance.

Turnbull and his wife seem

to have arrived in Charleston in November 1795. They became part of John J.L.

Sollee’s repertory company at the City or Church-Street Theatre, opened in

1792 as a rival to the Charleston Theatre on Broad Street. Sollee, a French

immigrant, brought the core of his company down from Boston, arriving on

November 6; a list of the actors in the City Gazette that day

includes “Mr. and Mrs. Turnbull, just arrived from England” (Willis 292).

The Turnbulls worked through a grueling season with seventy-nine

performances running from November 1795 through to early May 1796, with two

plays and often extra musical interludes on each program. Along with many

now-forgotten plays, Turnbull appeared in The School for Scandal,

The Beaux Stratagem, She Stoops to Conquer, Catherine and

Petruchio (Taming of the Shrew), Hamlet, Romeo and

Juliet, Richard III, and Macbeth (Willis 312-316). In

addition to Scottish character parts in the farces that concluded each

evening’s performance, he also appeared as Fingal in Oscar and Malvina,

a loose adaptation from James Macpherson’s Ossian; as Glenalvon in Home’s

Douglas; and as Bauldy in the first production on the Charleston stage

of Allan Ramsay’s The Gentle Shepherd. Moreover, for the first of

his two benefit nights, he staged and took the lead role in the first

American performance of his own short play, The Recruit: A Musical

Interlude, written and performed for the Dumfries Theatre in January

1794 and printed that year in his Poems.

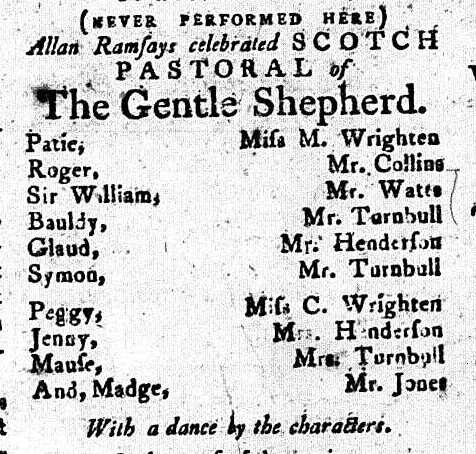

Advertisement for the first

Charleston production of Allan Ramsay’s The Gentle Shepherd

(Charleston Herald, April 29, 1796)

But there had been

contractual disputes in the Sollee company, and by mid-May, as soon as

Sollee’s season ended, Turnbull began appearing at the other Charleston

theatre, on Broad Street, headed by the English actor-manager Thomas West.

Turnbull’s move may have had political overtones, because the City Theatre

was initially associated with Republicans, while West and the Charleston

Theatre had Federalist connections (Rogers 110-112); in later years, when

Charleston had only one theatre company, the political distinction

disappeared. In the fall of 1796, when West went north to Virginia, he took

the Turnbulls with him. They probably began in Norfolk in mid-October, had

at least one performance in Petersburg on October 25, and opened in Richmond

on November 24 (Shockley 119-134; p. 122). The Turnbulls reprised many of

their roles from Charleston, three nights a week. Turnbull again starred as

Fingal. After Richmond, it was back to Petersburg, from mid-January to early

March, 1797 (Wyatt, “Three Petersburg theatres,” 90-91).

Meanwhile the rival company,

which alternated between Boston and Charleston, had been recruiting other

British theatrical star-couples, notably Mr. and Mrs. Williamson (nee

Fontenelle) for 1797-98. The Turnbulls had known both Williamsons in

Dumfries in 1792-1795, where Mrs. Williamson as Louisa Fontenelle had

performed to the plaudits of Burns himself. It seems to have escaped

comment in recent Burnsian scholarship that Gavin Turnbull had been among

the actors arrested with Williamson in Kendal that last winter, hauled

before the Earl of Lonsdale on charges of vagrancy, and sent to the house of

correction in Penrith (Henley-Henderson II: 354: more about this below). At

Mrs. Williamson’s benefit night in Charleston on March 6 1798, she proudly

delivered the prologue “written at her particular request, by the late Mr.

Robert Burns of Scotland, the Ayrshire Bard, from his manuscript and not

yet printed in his works” (Willis 395; cf. Poems, ed. Kinsley, II:

721-722).

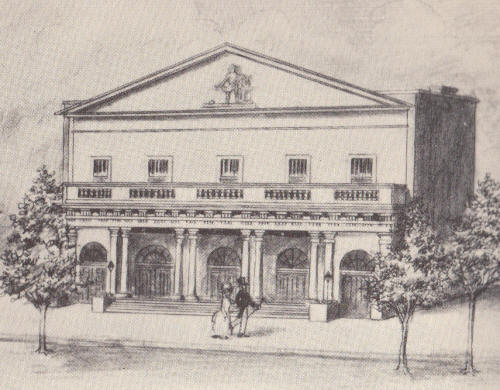

The Charleston Theatre,

Broad Street, 1793

In 1798, control of Sollee’s

company passed to a partnership involving the Williamsons and the French

acrobat Alexander Placide. Louisa Fontenelle Williamson died in 1799, and

Williamson himself in 1802. It may be significant that the Turnbulls

rejoined the company only after Louisa’s death, but while her husband was

still living. Both Turnbulls are listed as acting with the Williamson-Placide

company in Charleston continuously from the 1799-1800 season through to the

1806-1807 season (Hoole, pp. 65 ff.; cf. detailed cast-lists in Sodders). In

addition, in 1800-1806, the Turnbulls went with the same company for shorter

seasons in Savannah, Georgia, then a city half Charleston’s size (Patrick

esp. pp. 41-47). They were useful repertory actors, but hardly stars. By

1807, in Hamlet, instead of playing Hamlet’s friend Horatio, Turnbull

had the less demanding role of the Player King. By then he was forty-two,

and ready to retire from the theatre. On May 30, 1807, presumably for his

final benefit before retiring, he reprised the lead in his old play The

Recruit (Hoole p. 73). Mrs. Turnbull is listed in the company without

her husband in 1807-1808 and again in 1809-1810. Gavin Turnbull returned

without his wife to a much-scaled-back company for one last season in

1812-1813, after Alexander Placide’s death (Hoole, p. 79). There was no

theatre company in Charleston in 1813-1815, because of the war with Britain,

and Turnbull died early in 1816.

What had Turnbull been doing

since the summer of 1807? The occupation of “teacher” in the 1813

naturalization record is confirmed by the city directories, which listed him

in 1807 as “comedian,” but as school master in 1809 and 1813. In 1808 and

1809, as Professor Radcliffe notes, he also published poems in the

prestigious Philadelphia magazine The Port Folio, “Ode to Suspicion”

in 1807, and ‘”Elegy on my Auld Fiddle” in 1808, as well as in Virginia and

New York newspapers. Naturalization required that Turnbull have been

resident in Charleston for the three years before 1813, so even if he

traveled elsewhere, Charleston remained his home base.

In adopting a theatrical

career, Turnbull had certainly not abandoned his ambitions as a poet. During

his first spring in Charleston, poems by “Mr. G. Turnbull, of the

Church-Street Theatre,” appeared regularly in two local newspapers, the

City Gazette and the Columbian Herald. Professor Radcliffe

mounted some Turnbull poems on his Spenser website, noting that the

newspaper appearances were often reprints from Turnbull’s 1788 book or his

briefer 1794 pamphlet. So far, I’ve found over fifty separate poems with

Turnbull’s name or initials in the Charleston papers from 1796 alone, most

but not all of them reprints, and the same papers have a few unsigned or

pseudonymous pieces that it is tempting to think might also be Turnbull’s.

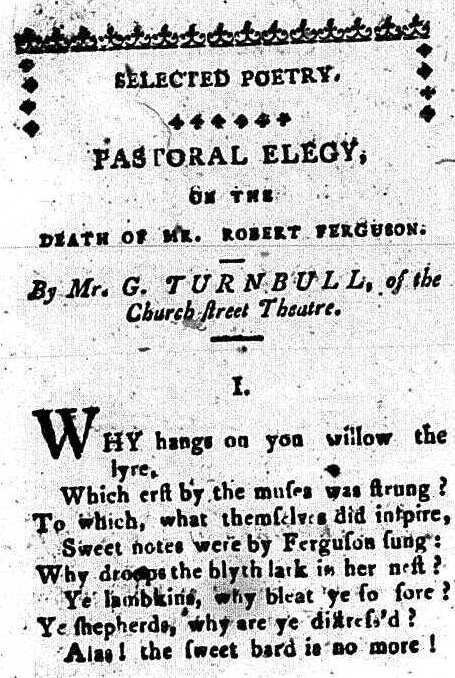

Gavin Turnbull’s elegy on

Robert Fergusson

(Charleston Herald, March 21, 1796)

Prominent among Turnbull’s

newspaper contributions were poems on Scottish topics, though I haven’t yet

come on any American reprinting of his poem dedicated to Burns. His moving

tribute to Robert Fergusson (Columbian Herald, March 21, 1796) is

formal and neoclassical, but his more playful tribute to Allan Ramsay, a

prologue to Ramsay’s Gentle Shepherd (Columbian Herald, March

11, 1796), has Ramsay speaking in his own voice, as his departed spirit

describes taking his place among the Immortals:

When Death, that camsheugh

carl, had fell’d me,

And first Elysian souls

beheld me,

My auld blue bonnet on my

head,

And hamely Caledonian weed,

They cry’d, “preserve’s!

what’s yon droll body,

That gangs just like a niddy

noddy?

‘Tis but some poor auld

Scottish herd”.

“Na fash!” quo’ Hermes,

“he’s a Bard,

Sic as the deel a’ mae ye’ll

find,

And ane of the Dramatic

kind” ...

And a’ that had a spunk o’

grace

Gied me kind welcome to the

place.

Both those poems were

reprints, and the Ramsay monologue had been written first for the Dumfries

theatre. Turnbull seems to have functioned as the in-house theatre poet both

there and in Charleston. One piece not apparently previously in print was

his orotund “Prologue ... to The Heroine, A Comedy by William Reid

Blacksmith” (Columbian Herald, March 26, 1796) which is headed

“Written and spoken by Mr. Turnbull, at the Theatre, Dumfries.” I can’t

find anything else about Reid, or his play, but one might conjecture some

link to Turnbull’s earlier and quite different “Epistle to a Blacksmith” in

colloquial Scots (Poetical Essays, 188-190), which I had previously

thought might refer to the blacksmith-poet John Gerrond. In addition to

reprinting the five songs from his own play The Recruit (Columbian

Herald, February 19, 1796), he published a “Monody: Malvina to Oscar” (Columbia

Herald, March 22, 1796), clearly relating to the music-drama in which he

had appeared both in Dumfries and Charleston. Among new work for the stage,

Turnbull now published a group of seven songs he had written for the

nautical drama Just in Time (Columbian Herald, April 20,

1796). Also new was his “Epilogue” (Columbian Herald, April 20,

1796), beginning “All the world’s a stage,” written as the finale for his

benefit performance (March 12, 1796). Perhaps most revealing among his new

writing for the stage at this time was his “Ode to Columbus” (City

Gazette, supplement, March 5, 1796), probably a new prologue for the

patriotic theatrical extravaganza repeated year after year by the Charleston

theatre companies:

... Freedom, guardian of the

land,

In her right hand the hero

brings

By heaven appointed to

command

And curb the insolence of

kings.

Reinforcing his chosen role

as Charleston’s local bard was his 59-line poem “On the Late Fire” (Columbian

Herald, May 18), published a mere two days after a fire swept through

part of the city, and possibly intended for declamation at the theatrical

benefit soon staged for the disaster relief fund.

Some of Turnbull’s poems

show the characteristic nostalgia of the emigrant for his homeland. He

reprinted, for example, both his neoclassical “Ode to the Tweed” (Columbian

Herald, April 19, 1796), and his depiction of Ayrshire farm life “The

Cottage” (Columbian Herald, March 18, 1796), rather in the tradition

of Fergusson’s “The Farmer’s Ingle” or Burns’s “The Cotter’s Saturday

Night.” However, as Radcliffe notes, between its first printing in 1788 and

the Dumfries reprint of 1794, Turnbull had added to “The Cottage” a fifth

stanza, retained for Charleston publication, drawing a political message

from the picture of rural contentment in the original four stanzas, and

advising the spendthrift rich:

But cou’d your haughty minds

once condescend

To leave a while the

formulas of state,

Ye’d see sweet peace and

happiness attend

The humble cot, and at an

easy rate,

More real joy and bliss ...

One of his new poems in

Scots, “A Legacy” (Columbian Herald, March 24, 1796), the deathbed

monologue of a Scots schoolmaster with very little to bequeath, reinforces

the theme that happiness does not depend on wealth:

Now, Jook, if I should

chance to die,

And leave my hale estate to

thee,

‘Tis fit that ye should hae

a guess

Of what ye shortly may

possess;

Lest some ane sue ye fur a

share,

You, I appoint the lawfu’

heir

Of a’ my siller, goods, and

gear ...

.. what will much delight a

scholar

Ye’ll get an inkcase and a

roller,

A pencase of a spleuchan

made,

A broken knife that wants

the blade,

A pair of specks that want

the een,

Yet better specks were never

seen ...

A psalm book and a bagpipe’s

drone,

A mouse trap and a

lexicon....

Another new poem, published

that first summer in Charleston, counsels a recent immigrant friend to be

realistic in his expectations. Entitled “Ode to a Friend Dissatisfied with

his Situation” (Columbian Herald, May 23, 1796), the poem describes

the vanity of always expecting to find happiness elsewhere:

In vain from place to place

we roam,

In vain we quit our native

home,

In vain explore tempestuous

seas,

To purchase happiness and

ease.

And hope to find serener

skies

Where, undisturbed,

contentment lies.

......

Bright reason wisely

whispers “Care,

Weak man, will haunt thee

ev’rywhere:”

Content alone can boast the

charm

That can the busy fiend

disarm,

And care will ever fly the

cell

Where innocence and Virtue

dwell.

Perhaps surprisingly,

Turnbull never (as far as we know) managed to publish a new collection of

his poetry in America. He certainly made several efforts to do so. The

first was when he was in Virginia, in Petersburg, early in 1797. The

proposal in the Virginia Gazette on January 31 invited subscriptions

at one dollar for Poems, Pastoral, Descriptive, and Elegiac; with Seven

Poems in the Scottish Dialect, which sounds very like a straight reprint

of his 1788 collection, and follow-up announcements on March 10 and June 5

promised the book was ready to go to press (Wyatt, in Preliminary

Checklist, p. 16). Radcliffe notes a second subscription announcement

in 1800, in the South Carolina State-Gazette, published in

Charleston. Then, after Turnbull’s death in 1816, a third proposal was made

in Charleston, to publish a collected edition of his poems, “with an

additional Canto to his Bard, and other original Poems, not hitherto

published; also his Lectures, Moral, Classical, and Satirical,” both as “a

just tribute to departed genius,” and “to add to the comfort of an aged

Widow” (Charleston Courier, June 3, 1816). This was to be

substantial book of 300 pages, costing two dollars, but like the two

previous editions proposed in America, there is no record of it ever

reaching publication. Turnbull’s last years as a schoolmaster had not

brought success or security, for the 1816 advertisement urges potential

subscribers to consider “the melancholy fate of genius crushed by indigence”

and the “sad condition that attends the widowed partner of his hapless

destiny.”

Despite the abundant

information on Turnbull’s life in Charleston, there are still some blank

spaces. Like Burns, he had had masonic connections in Ayrshire, and

Charleston, a longtime centre of American freemasonry, was the birthplace in

1801 of the Scottish Rite (33rd Degree), yet I have not found

Turnbull in the published sources on Charleston masonry. Neither does

Turnbull feature in the histories of the St. Andrew’s Society of Charleston,

founded in 1729, not even as a deserving candidate when they wanted a

schoolmaster in 1809, nor to declaim Scottish poems on the opening of their

hall in 1815, an honour that went to another recent Scottish immigrant, the

elocutionist James Ogilvie. And despite stray references in the later

poetry, Turnbull’s political views in the mid-1790s remain unclear, though

they surely played some role in his decision to emigrate, just as the

hostile political environment had done in his friend and fellow-poet

Alexander Wilson’s decision to go to Pennsylvania. Robert Crawford depicts

Turnbull’s politics as relatively conformist in contrast to Burns’s

(Crawford, p. 376, 385) pointing particularly to his satirical poem “The

Clubs,” first published in Dumfries and reprinted in Charleston (Columbia

Herald, March 15), which includes a specific disavowal of seditious

groups. However, the extra stanza Turnbull added to “The Cottage” for 1794,

his arrest in Cumberland before he emigrated, the political connections of

the City Theatre in Charleston, some of the unsigned poems on British

politics in the Columbian Herald in 1795-1796, and his continuing

links with Alexander Wilson, all suggest there is more to find out.

There is, however, one

tantalizing hint in Turnbull’s story that may lead back more directly to

Dumfries and Burns—the incident just mentioned, in 1795, when the Dumfries

actors, Turnbull among them, were arrested by the Earl of Lonsdale. One

result was the poetic account “Fragment—Epistle from Esopus to Maria,”

usually attributed to Burns (Kinsley II: 769-771). It is variously titled in

different editions, and in one transcript by John Syme is headed

“Fragment—Part Description of a Correction House.”

From these drear solitudes

and frowzy cells,

Where Infamy with sad

repentance dwells;

Where Turnkeys make the

jealous portal fast,

Then deal from iron hands

the spare repast; (lines 1-4)

Written in the voice of J.

B. Williamson (“Esopus”), it includes references to several plays that would

later feature in the repertoire in Charleston, including Oscar and

Malvina. The poem has special interest because it includes a

third-person description of Burns himself during the Dumfries years,

portraying him as a marginalized radical, at risk of arrest for sedition,

confinement in the hulks (prison ships) in London, and then transportation

to Australia like the Scottish radical Thomas Muir of Huntershill:

The shrinking bard adown an

alley sculks,

And dreads a meeting worse

than Woolwich hulks—

Tho’ there his heresies in

Church and state

Might well award him Muir

and Palmer’s fate (lines 39-42).

While the majority of

scholars accept Burns’s authorship, the evidence for it is all late or

inferential. There is no manuscript in Burns’s hand, and the poem was first

published by Allan Cunningham in 1834; Cunningham’s transcript is in the

British Library, and Syme’s transcript was first published by J. C. Ewing in

1935. The attribution itself comes from the transcripts, not from letters

or other contemporary reference. A detailed case against Burns’s authorship

was mounted in 1930 by J. DeLancey Ferguson, but Kinsley in 1968 retained

the poem as authentic, rejecting Ferguson’s argument in part because

“evidence is wanting that there was anyone other than Burns in Dumfries

society who was capable of writing” the better passages in the poem (Kinsley

III: 1471). Turnbull’s poetry varied greatly in quality, and at its best

never rivals Burns at his best, but Turnbull was documentably

present, as Burns was not, at the events that the first part of the poem

commemorates. Much about the poem remains problematical, not least the

bitterness with which Burns himself is depicted in lines 49-56, and I intend

to explore the issues more fully in future, but for those who already doubt

Burns’s authorship, Turnbull is perhaps an alternative worth

consideration.

This is necessarily an

interim report. Each day, I have been coming on further references that

need following up. Everything isn’t available on Google, and not everything

can be borrowed through Inter-Library Loan (though my colleagues give it

their best effort). What we can be sure of is that, though he left Scotland

in 1795, and in due course took American citizenship, Turnbull never gave up

either his cultural identity as a Scot or his ambition as a poet.

Acknowledgements

Several of the people who helped me in this research are

acknowledged in the text above. In addition, I want to thank Kenneth

Simpson, Gerald Carruthers, Corey Andrews, and Frank Shaw for their interest

and feedback on the project, and David Radcliffe for his generous

encouragement when I first emailed him that I was following up his earlier

Turnbull discoveries.

References

Butler,

Nicholas, Votaries of Apollo: the St. Cecilia Society and the Patronage

of Concert Music in Charleston, South Carolina, 1766-1820 (Columbia, SC:

University of South Carolina Press, 2007).

Carruthers, Gerard, “Robert Burns’s Scots Poetry Contemporaries,” in

Burns and Other Poets, ed. David Sergeant and Fiona Stafford (Edinburgh:

Edinburgh University Press, 2012): 38-52.

Crawford, Robert, The Bard: Robert Burns, A Biography ((Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press, 2009).

[Crichton, Thomas], in his “Biographical Sketches of Alexander Wilson,” in

The Weaver [Paisley], 2 (1819); extract reprinted in Paterson,

Appendix, pp. 23-24.

Ewing,

J. C., “Burns’s ‘Esopus to Maria’,” Burns Chronicle, 2nd.

Series, 10 (1935): 32-38.

Ferguson, J. DeLancey, “Robert Burns and Maria Riddell,” Modern Philology,

28:2 (1930): 169-184.

Hagy,

James W., City Directories for Charleston, South Carolina for the Years

1803, 1806, 1807, 1809, and 1813 (Baltimore; Clearful Company, 1995).

Hemperley, Marion R., “Federal Naturalization Oaths, Charleston, South

Carolina, 1790-1860, part 3” South Carolina Historical Magazine, 66

(1965), 219-228 (p. 225).

Holcomb, Brent H., South Carolina Naturalizations 1783-1850

(Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing, 1985).

Hoole,

W. Stanley, The Ante-Bellum Charleston Theatre (Tuscaloosa:

University of Alabama Press, 1946).

Kinsley, James, ed., The Poems and Songs of Robert Burns, 3 vols.

(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968).

Lindsay, Maurice, The Burns Encyclopedia, 3rd ed. (London:

Robert Hale, 1980).

Paterson, James, The Contemporaries of Burns, and the More Recent Poets

of Ayrshire (Edinburgh: Hugh Paton, etc., 1840).

Patrick, J. Max, Savannah’s Pioneer Theatre from its Origins to 1810

(Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1953).

Radcliffe, David Hill, “Gavin Turnbull, 1770 ca.-1816,” in Spenser and

the Tradition; English Poetry 1579-1830, at

http://spenserians.cath.vt.edu/AuthorRecord.php?&action=GET&recordid=33336&page=AuthorRecord

_________________, ‘Turnbull, Gavin (c. 1765-1816),” Oxford Dictionary of

National Biography, ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison (Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2004), 55: 587; updated version on the web by

subscription at:

http://www.oxforddnb.com.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/view/article/64791?docPos=7

Rogers,

George C., Jr., Charleston in the Age of the Pinckneys (Norman, OK:

University of Oklahoma Press, 1969; repr. Columbia, SC: University of South

Carolina Press, 1980)

Roy, G.

Ross, ed., Letters of Robert Burns, 2nd ed., 2 vols

(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985).

Seilhamer, George O., History of the American Theatre: New Foundations,

1792-1797 (Philadelphia: Globe Printing House, 1891).

Shockley, Martin, The Richmond Stage, 1754-1812 (Charlottesville:

University Press of Virginia, 1977).

Sodders,

Richard P., The Theatre Management of Alexandre Placide in Charleston,

1794-1812, 2 vols., unpub. Ph.D. diss. (Louisiana State University,

1983).

Turnbull, Gavin, Poetical Essays (Glasgow: David Niven, 1788; repr.

ECCO Print Editions, n.d. [2012]).

_____________, Poems (Dumfries: for the Author, 1794; repr. ECCO

Print Editions, n.d. [2012]).

Willis,

Eola, The Charleston Stage in the XVIII Century with Social Settings of

the Time (Columbia, SC: the State Company, 1924; repr. New York: Blum,

1968).

Wyatt,

Edward A., IV, “Three Petersburg Theatres,” William & Mary Quarterly,

2nd series, 21:2 (April 1941): 83-110.

_________________, ed., Preliminary Checklist for Petersburg, 1786-1876:

Virginia Imprint Series, no. 9, series eds. John Cook Wyllie and

Randolph W. Church (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1949). |