|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

It is always good to

hear from Patrick Scott, longtime supporter and contributor to the pages of

RBL!. Patrick is Editor, Studies in Scottish Literature and

Distinguished Professor of English, Emeritus, at the University of South

Carolina Libraries. He has been a loyal friend of Robert Burns Lives!

for many years, and it is always a joy to have him contribute to our web

site. You will find the following article on the relationship between poet

Marion Bernstein and Robert Burns to be like other articles submitted by

Patrick - interesting, fascinating, and with something new to consider.

Welcome back home, Patrick! (FRS: 8.8.13)

A Victorian Admirer

Writes Back:

Marion Bernstein and Robert Burns

By

Patrick Scott

Till twenty years ago,

almost no one had heard of the Glaswegian feminist poet Marion Bernstein

(1846-1906). Like most other late Victorian Scottish writers, Bernstein was

not exempt from the idealization of Robert Burns that characterized the

period, but she also had a distinctive, feisty independence in some of what

she wrote about his work. A recently-published book, the first collected

edition of Bernstein’s poetry, makes it possible for the first time to

examine the full range of her responses to Burns.

Marion Bernstein was

born in London, the second child of a German immigrant father and a

well-brought-up English mother. Following an unnamed childhood illness, she

wrote, “I grew up to womanhood feeble and lame,” doomed to spend “years on

my couch.” Her father’s business failure, growing debt, and mental breakdown

led to his death in 1861, leaving the mother and family to scrape together a

living running a lodging house, and eventually moving to Glasgow in 1874,

where the invalid Marion taught music and began publishing poetry. Over the

next thirty years, she published nearly 200 poems, and one of her poems was

included in D.H. Edwards’s multivolume anthology Modern Scottish Poets,

vol. 1 (1880). Over time, however, Bernstein’s poetry, locally published in

ephemeral format, became more or less invisible.

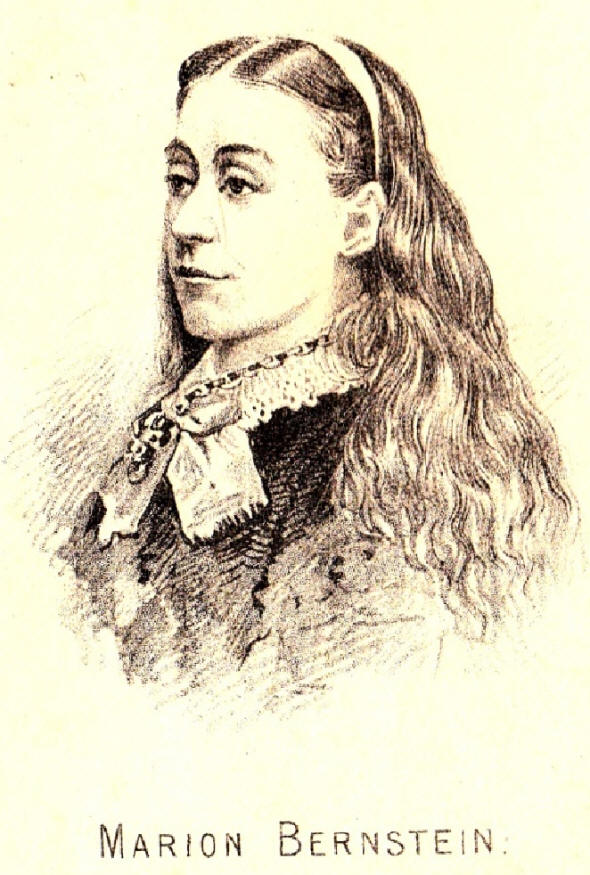

Frontispiece portrait

of Marion Bernstein

From

Mirren’s Musings (Glasgow,1876)

G. Ross Roy Collection, University of South Carolina Libraries

Current awareness of

Bernstein’s writings began when Tom Leonard included a few of her poems in

his anthology Radical Renfrew (1990), and since then interest has

grown steadily. Other Scottish anthologists have followed Leonard’s lead;

significant articles about or including Bernstein have been published by

Edward H. Cohen and Linda Fleming, Florence Boos, Valentina Bold, and

others; and she has been at least mentioned in several recent Scottish

literary histories. Her scathing reaction to domestic violence, male

complacency, and economic exploitation both in Glasgow and during the

Clearances has rightly attracted critical attention. Often her poems seem

almost impromptu responses to something in the newspaper, as with her

“Wanted A Husband,” a satirical rewrite on the conventional idealized

Victorian wife:

Wanted a

husband who doesn't suppose,

That all

earthly employments one feminine knows-

That she'll scrub, do the cleaning, and cooking, and baking,

And plain

needlework, hats and caps, and dressmaking.

Do the family washing, yet always look neat,

Mind the

bairns, with a temper unchangeably sweet,...

Men expecting as much, one may easily see,

But they're

not what is wanted, at least not by me.

(Song

of Glasgow Town, p. 28)

In 1875, long before the

Suffragette Movement, Bernstein offered a vision of a woman-dominated, and

much improved, political future:

I dreamt that the

nineteenth century

Had entirely passed

away,

And had given place to a

more advanced

And very much

brighter day. ...

There were female chiefs

in the cabinet,

(Much better than

males I’m sure)

And the Commons were

three-parts feminine,

While the Lords

were seen no more.

(Song of Glasgow Town,

p. 53; and cf. p. 76).

However, despite the

increased interest in Bernstein, it has remained very difficult to get hold

of her poetry. Most of it was originally published in Scottish newspapers,

chiefly during the 1870s in the Glasgow Weekly Herald and Glasgow

Weekly Mail, and almost half the newspaper poems have never been

reprinted. Bernstein collected many of her earlier poems in her only book,

Mirren’s Musings (1876), but copies are exceedingly rare. The

international bibliographical database WorldCat lists copies of the book

only in the British Library and the National Library of Scotland, so that

Ross Roy was overjoyed when a couple of years ago Ken Simpson found him one

that he could add to the Roy Collection.

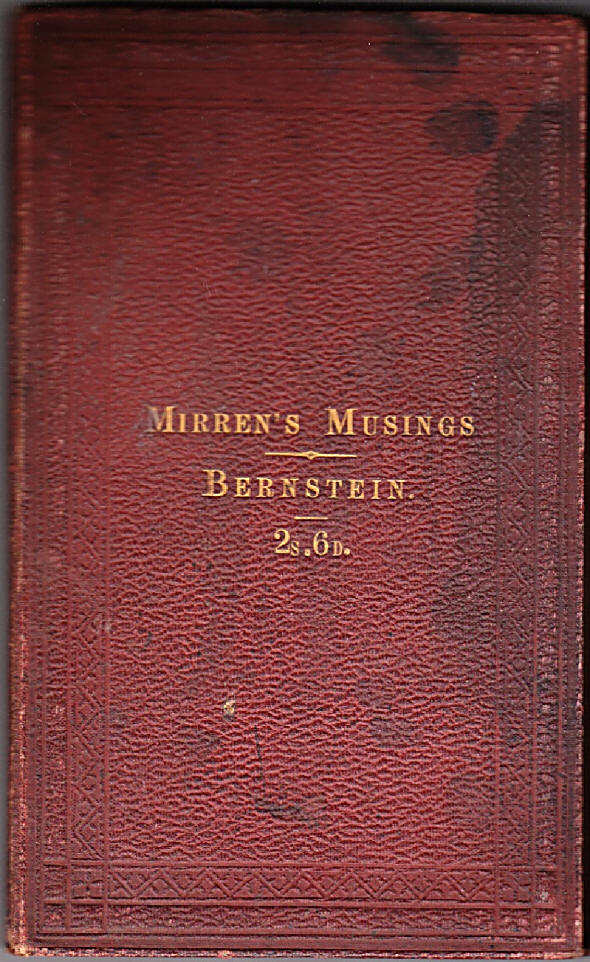

Marion Bernstein’s

only book (Glasgow, 1876)

From the G.

Ross Roy Collection

That there was still

much more of Bernstein’s writing to be discovered was made clear in 2009

when an article by Prof. Cohen and Dr. Fleming reprinted twelve poems that

Bernstein had not included in her book, and Cohen and Fleming followed up in

2010 with the first full account of Bernstein’s life. Now the same

scholars, with Ann Fertig, have edited the very first collected edition of

Bernstein’s poems, under the title A Song of Glasgow Town (Glasgow:

Association for Scottish Literary Studies, 2013). With over three hundred

pages, nearly 200 poems, a thirty-page introduction, and bibliographical

information, it allows examination for the first time of the full range of

Bernstein’s work.

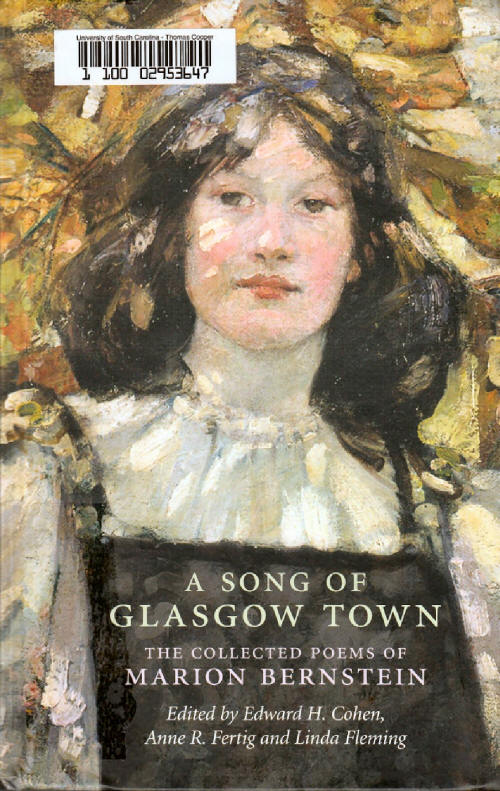

A Song of Glasgow

Town: The Collected Poems of Marion Bernstein

edited by

Edward H. Cohen, Anne R. Fertig, and Linda Fleming

Glasgow:

Association for Scottish Literary Studies, 2013.

ISBN 978-1-906841-13-1

One aspect of

Bernstein’s work that the new collection makes much more visible is her

continuing interest in Robert Burns and his poetry. The poems Bernstein

wrote directly about Burns are perhaps less original than those in which she

engaged with what he was saying, and wrote back in answer to him, just as

she had written verses in answer to her contemporaries. None of them are

well known to Burnsians, and it seems worth examining them one by one.

Bernstein’s two poems

directly about Burns himself were both written too late for inclusion in

Mirren’s Musings. Both are interesting as spirited defenses of Burns

against Victorian adulation and detraction, but neither shows her at her

poetic best: I have been ruthless in excerpting them here. The first,

published in the People’s Journal (February 3, 1883), contrasts the

financial struggles of Burns in his lifetime with the amount that her

Victorian contemporaries spent on commemorating him. The ASLS editors

comment acutely that she is writing as much about her own sense of being

neglected as about Burns:

While others will tell

of thy triumphs,

Thy genius, and thy

fame,

I can only think of thy

sorrows

Whene'er I hear thy

name.

I think of the heart of

a poet

Always unfit to bear

Sad poverty's heavy

burden

Of sordid, ceaseless

care.

Poor Burns! how thy

sensitive nature

Fretted beneath the

strain

Of want and debt and

dependence,

A threefold, galling

chain. …

Ah! the price of thy

meanest statue

Might then have changed

thy fate;

Dost thou see the wealth that is lavished

Over thy grave, too

late?

Dost thou witness how

oft the poet

Is deemed of little

worth

Till the voice of the

minstrel is silent,

And the spirit passed

from earth? …

(Song of Glasgow Town,

p. 158)

Bernstein’s second poem

about Burns, published in the Glasgow Weekly Herald (January 29,

1887), confronts Victorian criticism of Burns’s sexual behavior, charitably

arguing that Burns repented of his sins (by marrying Jean), and that his

critics should accept his sincerity:

Oft it moves my

indignation

That the envious eye

discerns

Nought of holy

exaltation

In the life of Robert

Burns.

On his faults will many

dwell,

His repentance few will

tell. …

Those who love the

Psalms of David

Should not sneer at

Robert Burns;

Each has sinned, and

each is savéd,

Each to God repentant

turns;

And God never hides His

face

From a soul that seeks

His grace. …

Thus hath Scotland's

sweetest poet

Been defamed and

slandered long;

Those who love him best

should show it

Nor permit this cruel

wrong.

Suffer not reproach to

rest

On the mem'ry of our

best.

Now let Scotland's

justice waken

For the Bard whose songs

she sings;

Let detraction's dust be

shaken

Off, as from an angel's

wings.

Even God would ne'er

rebuke

Any sins his saints

forsook. …

(Song of Glasgow

Town, pp. 183-185)

Burns’s poems were among

the touchstones that Bernstein used when the poetry editor of the Weekly

Mail decided to exclude “amatory verses.” She wrote no less than three

poetic attacks on this policy, one on the grounds that it would have

excluded too many poems that everyone admires, including, of course, poems

by Robert Burns:

For the Editor thinks love alarming,

And for lovers professes disdain;

He'd deny that there's anything charming

In 'Sweet Jessie, the Flower o’ Dunblane.'

He would sternly refuse 'Annie Laurie,'

Drive the bold 'Duncan Gray' to despair,

And quite scornfully scoff at the lassie

Who is pining for 'Robin Adair.'

I don't even believe 'Highland Mary'

His frigidity ever could move;

He has shown himself wond'rously wary

In avoiding 'The Power of Love'!

(Song of Glasgow

Town, p. 32)

Much more distinctive,

however, and more characteristic of Bernstein’s general poetic voice, are

two poems that she wrote, not about Burns, but in reaction against two of

his best-known poems. Burns’s poems have always provoked dialogue from

other poets or versifiers. In his own time, his “Address to the De’il” was

soon met with Ebenezer Picken’s “The De’el’s Answer to his Verra Worthy

Friend R. Burns,” and indeed several other similar attempts. More recently,

there have been replies to Burns’s “Tam o’ Shanter” from the viewpoint of

Tam’s longsuffering wife Kate, by the Canadian mathematician Colin Blyth,

and to Burns’s “To a Mouse” from the mouse’s viewpoint, by the Scottish poet

Liz Lochhead.

The very first of

Bernstein’s published poems had been a riposte to Burns. Her poem “On

hearing ‘Auld Lang Syne’” was first published in the Glasgow Weekly Mail

(February 28, 1874), and then included in her book Mirren’s Musings.

Bernstein, severely handicapped from childhood, losing her father to

insanity as a teenager, and struggling throughout her life against illhealth

to make a living as a music teacher, finds that Burns’s appeal to boyhood

happiness and adult friendship simply doesn’t match her own experience:

Oh! tell me not of auld lang syne,

For I would fain forget

Those bygone days, whose

memory

Brings nothing but

regret.

For I have far outlived

the time

When thoughts of days

gone by

Could call the smile upon my lip,

The light into mine eye

.

Ah! now ’tis not with

smiles, but tears,

That I can call to mind

The vanished joys of

bygone years,

The years of auld lang

syne.

The joys of auld lang

syne are fled.

My early hopes have

flown,

The friends who have not

changed are dead,

And I am left alone.

(Song of Glasgow

Town, p. 3)

Towards the end of her

life, Bernstein took on another of Burns’s songs, this time in protest

against the destructive effects of alcoholism in the Glasgow and Scotland of

her time. This was a rewriting of Burns’s “Willie brew’d a peck o’ maut,”

from the Scots Musical Museum (Kinsley I:476-477). Bernstein’s

version appeared in the Glasgow Weekly Herald (February 8, 1902),

changing the reiterated protest of Burns’s drinkers, “We are na’ fou’” into

the abstainers’ refrain “We are na fools”:

Willie brewed a peck o’ maut,

An' ca'd the neebors ben tae pree,

Noo, Willie wisna' worth his saut,

He lo'ed o'er weel the barley bree.

As canny Jock met Donald Clyde,

'Are ye gaun ben tae Will's?' said he.

Said Donald, 'Na, we'd better bide

Awa' frae ony drucken spree.

We are na fools, we're no sic fools

As waste guid siller on the spree;

Let folly think there's joy in drink,

But I'll no taste the barley bree.

Will winna work, an' canna play,

A drucken ne'er-dae-weel is he.

His wife gangs oot tae work a' day,

While Willie tastes the barley bree.

He has the makin's o’ a man,

But ne'er made up, it seems tae me.

An ass is wiser, if he can

Hae sense tae leave the barley bree.

We are na fools, we're no sic fools

As waste guid siller on the spree;

Let folly think there's joy in drink,

But I'll no taste the barley bree.

Willie spent fu' half the nicht

Drink, drinkin' wi' the folk aroun',

An' at the blink o’ mornin' licht

He lay in sleep sae still an' soun',

He'll wake nae mair till Judgment Day,

An’ O, what will the wakin' be?

Wae's me, tae live sae far astray,

An' sic a waefu' death tae dee!

We are na fools, we're no sic fools

As waste guid siller on the spree;

Let folly think there's joy in drink,

But I'll no taste the barley bree.'

(Song of Glasgow Town,

p. 214)

While the idea of a

temperance rewriting of Burns sounds a sure loser, it takes both knowledge

of the original song and an acute ear for Burns’s language and rhythms to

carry the idea off, as Bernstein does, with such verve and aplomb. To my

mind, improbably, this last example is the best, because the most Burnsian,

of Bernstein’s Burns poems.

Bernstein’s writing

about Robert Burns is certainly not what has led to the modern revival of

interest in her writing. That rests on her scathing social observation of

late Victorian Scotland urban life, her proto-feminist vision, and her

strong moral commitment to fairness and equality. But Bernstein’s writing

about Burns gives an interesting and individual insight into the way Burns

was perceived, idealized and often distorted, in the period when his

achievements were most widely recognized.

References:

Bernstein, Marion,

Mirren’s Musings, A Collection of Songs and Poems (Glasgow: McGeachy,

Bernstein, 1876).

_________, A Song of

Glasgow Town: the Collected Poems of Marion Bernstein, ed. Edward H.

Cohen, Anne R. Fertig, and Linda Fleming (Glasgow: Association for Scottish

Literature Studies [vol. 42], 2013).

Bold, Valentina, in A

History of Scottish Women’s Writing, ed. Douglas Gifford and Dorothy

McMillan (Edinburgh: Edinburgh Univ. Press, 1997): 246-261.

Cohen, Edward H., and

Linda Fleming, eds, “A Scottish Dozen: Uncollected Poems by Marion

Bernstein,” Victorians Institute Journal 37 (2009): 93-119.

_______________________________, “Mirren’s Autobiography: the Life and Art

of Marion Bernstein (1846-1906),” Scottish Literary Review 2:1

(2010): 59-76.

Leonard, Tom, ed.,

Radical Renfrew (Edinburgh: Polygon, 1990). |