|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

Here is an interesting

connection, slight as it may be, between Robert Burns and John Galt,

“the other great Ayrshire writer.” Were they the best of friends? No and

neither did they frequent the pubs together, but they had one thing in

common – they were distant kin being, I believe, second cousins. There

was twenty years separating them with Galt being the youngest. Because

of this age difference, there is little between the two except their

bloodline and their desire to write. One wrote books, the other a book.

One dealt in prose and the other primarily in poetry and songs. Yes, one

went to debtor’s prison while the other thought he was going there too

as he lay on his death bed. One was the son of a sea captain who told

stories around the fireplace that caused his son to go see the world for

himself as a traveler to Canada and Europe. As Chris Rollie points out

in his fine book Robert Burns in England, Burns went to England but

ventured into the country for only a few miles. One founded cities and

made good money while the other could only dream of such money -- and

none of us will ever forget him on his death bed begging for a few

pounds. One is enshrined in the hearts of men and women all over the

world and the other, by contrast, is hardly known by our world’s

population. I could go on with other comparisons, but John McGee’s

wonderful article on John Galt awaits. Enjoy.

Our writer, Ian McGhee,

or John if you prefer, was born and brought up in Ayrshire, Scotland and

has recently returned there to live. After a successful career in the

public service dealing mainly with business and industry, he enrolled at

Glasgow University to study Scottish Literature and was awarded a first

class Honours degree in 2013. He is currently completing a Masters in

John Galt's North American corpus.

I’m grateful for John’s

assistance with this article and for the several pictures he has shared,

and I also appreciate Gerry Carruthers putting the two of us together

for this piece. A new John Galt Society was just formed in Glasgow this

month with dues of only £10 annually. I jumped at the chance to join as

a means of learning more about John Galt from these scholarly Scottish

men, and I hope you will join me in membership. There is so much more to

Scotland than just Robert Burns. So please contact me and I will put you

in touch with the person in charge. (FRS: 12.18.14)

John Galt:

The Other Great Ayrshire Writer

by Ian McGee

Ian McGhee

John Galt

Robert Burns was not the

only great literary figure to emerge from Ayrshire. John Galt was only

twenty years younger than Burns but can fairly be said to have been as

innovative in prose as his more famous countryman was in poetry. Galt

anatomised the small communities of the West of Scotland at a time of

unprecedented social, religious and economic change, pioneered the

political novel, took the concept of first person narration to new

heights of irony and leavened it all with a richly comic yeast. And all

the while he considered that his writing was a poor second to his

pursuit of fame and wealth through business.

Of course it may not just

be the Ayrshire air which produces writers. The genes may have a

greater influence. David Knight, in Guelph Ontario, the city founded by

Galt, published a new edition of Galt’s story The Omen in 2014 and in

his foreword says that Galt’s father John was a first cousin to Burns

and also a first cousin to John Allan, the foster father of Edgar Allan

Poe. There is evidence, too, that Galt was a founder member of Greenock

Burns Club, the oldest in the world.

John Galt was born in

Irvine in 1779. His family moved to Greenock in 1789 and it was there

that he completed his education and first started work. In 1804 he went

to London to seek his fortune, a prize which hovered tantalisingly out

of reach for all his life. Bankrolled by his father he bought into a

partnership which went bankrupt in 1809. Discharged by his creditors he

went travelling for more than 2 years around the Mediterranean, where he

fell in with Lord Byron, and through Europe.

On his return to London

he tried his hand at a number of ventures, the most successful of which

was as a Parliamentary Agent; what we would now call a lobbyist. He was

responsible in 1819 for the successful passage of the necessary

legislation to allow completion of the Union Canal linking Edinburgh and

Glasgow and this brought him to the attention of some Canadian gentlemen

who were seeking compensation from the British Government for losses

they had suffered defending Canada from the US invasion during the war

of 1812 – 14. Galt undertook to represent them on a no-win, no-fee

basis.

He gradually discovered

that while the Government was ready to offer the Canadians lots of

sympathy it would not hand over any cash. In his researches on the

matter he did, however discover that the Government held vast amounts of

land in Upper Canada (present day Ontario) and that it was not being

usefully or profitably developed. He therefore conceived the idea of

forming a company which would buy the land wholesale, put in some basic

infrastructure, divide it into manageable lots and sell it retail to

emigrants and settlers.

Galt’s ideas on land and

community development had been refined when he made a reconnaissance

trip to Canada in 1825 and reached there via the Genessee country of New

York State where he had made a detailed study of the operations of the

Holland Land Company and the similar firm of Goran & Phelps, both of

whom impressed him greatly.

The Canada Company was

duly formed, obtained its charter from the Government and purchased over

2 million acres in Upper Canada. Galt was appointed as its first

commissioner and arrived in York (present day Toronto) in December

1826. Until he returned to London in April 1829 Galt worked tirelessly,

founding the cities of Guelph and Goderich, receiving and providing for

settlers, and selling land, sometimes accepting labour in exchange and

sometimes payment in instalments. The methods he pioneered were adopted

by the Company after he left and kept it in profitable business until it

was wound up in 1954.

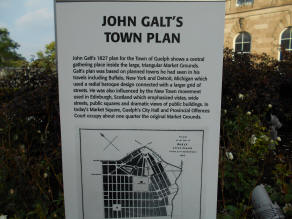

John Galt's Town Plan of Guelph

The Canadian sojourn had

a much less happy outcome for Galt personally. He had made three

serious errors. The first was that he failed to ensure that the

Directors of the Company accepted that they needed a medium term

strategy. They had invested in the expectation of short term profits

while Galt always knew that it would take time for profits to be

realised. Unfortunately, he tended to believe that if something was

obvious to him it would be equally obvious to every other intelligent

person. The Directors, however, became very nervous when they saw the

amounts of cash flowing out at a much greater rate than the money coming

in.

The second error was to

make an enemy of the Provincial Government in Upper Canada, headed at

that time by General Sir Peregrine Maitland, a man ‘crammed with the pet

prejudices of religion, flag and caste’ according to the Canadian

historian Arthur Lower. As a staunch Anglican Maitland viewed the

Presbyterian Galt with suspicion and, wrongly, suspected him of

harbouring radical and democratic tendencies. His despatches to the

London Government therefore presented Galt’s activities in an

unflattering light and added to the uneasiness which the Directors were

feeling. Galt was not entirely blameless since his relations with

Maitland were characterised at best as lacking tact and at worst as

being downright arrogant.

The third mistake, and

the straw which broke the camel’s back, was that Galt was a poor

bookkeeper. The Company’s accounts in Canada were a mess as the Company

discovered when they sent a representative to Canada to inspect them.

There was no question of malfeasance or embezzlement: Galt did not

divert any funds to his own pocket. In fact, shortly after his return

to London he was imprisoned for debt. He could, and did, argue with

considerable justification that his workload was too great for him to

keep on top of all the details. Nevertheless it was sufficient excuse

for the Company to recall him to London in April 1829 and to dismiss

him.

Galt’s business career

was now effectively over and within the next three years he suffered a

series of strokes. They caused him to retire to Greenock where he lived

quietly until his death in 1839. Throughout his life, no matter what

else he was doing, Galt wrote. There was no literary genre to which he

did not turn his pen. Journalism on politics, economics and society,

histories, biographies, travel books, short stories, novels, children’s

text books, poems and plays were all published under a variety of

pseudonyms and with varying degrees of success. Inevitably, with such a

prodigious output the quality is variable but at his best he has few

equals for illustrating universal truths through the examination of

village and small town societies.

His first great literary

success came with the publication in monthly parts from March 1820 in

Blackwood’s Magazine of The Ayrshire Legatees, an epistolary novel

concerning the Pringle family’s time in London in pursuit of a legacy

and the reactions to their letters back in the home village just outside

Irvine. It was quickly published in book form in 1821 and in the same

year was followed by The Annals of the Parish, the purportedly

autobiographical account of the sixty years ministry (from 1760 to 1820)

of the Reverend Micah Balwhidder in the parish of Dalmailing (modelled

on the village of Dreghorn, again close to Irvine). In rapid succession

there came Sir Andrew Wylie of that Ilk (1822), The Provost (1822) and

The Entail (1822). The Provost is set in the Royal Burgh of Irvine and

covers the same period as The Annals. It is another of Galt’s

faux-autobiographies and is a wickedly funny and masterly study of

small-town politics through the medium of ironic self-revelation. What

it tells us about the political animal is as true today as it was then.

Pencil drawing of John Galt

All of these novels,

which Galt preferred to call ‘theoretical histories’, provide valuable

information for social historians about the effects of economic,

religious and social change in rural and small town Scotland at the

beginning of the nineteenth century. Professor Christopher Whatley has

said that it is only now that historians are catching up with Galt and

uncovering incontrovertible evidence that what he was saying about

social and economic conditions and the reactions of people to them is

undoubtedly true and not invented for literary or dramatic purposes.

Galt then published a

series of historical novels of which Ringhan Gilhaize (1823) is the most

noteworthy. It may be considered as a defence of the Covenanters, or

rigid Presbyterians, whom Galt felt had been afforded too little respect

by Sir Walter Scott in Old Mortality. He returned to change in the

social order, and comedy, with The Last of the Lairds (1826) which,

because he was preparing to go to Canada, he allowed to be published in

a heavily bowdlerised form. It was not until 1976 that Ian Gordon

produced an edition of that novel which contained what Galt actually

wrote rather than the genteel ending which Blackwood forced on it.

After Canada Galt needed

to write since it was his only source of income. Among other things he

published Lawrie Todd (1830), based on his experiences in New York State

but drawing on, for the early part, the real autobiography of Grant

Thorburn, a Scotsman who had emigrated to New York City and to whom Galt

says he paid ‘an author’s, not a publisher’s price’ for the manuscript.

This was followed by Bogle Corbet (1831) which ranges from Glasgow to

London to the West Indies and, for the final third of the book,

Ontario. Both of these novels have their longeurs for they were padded

out to meet the publisher’s demand for a full three volumes but they

contain fascinating accounts of Galt’s views on emigration and community

building.

The best of his later

novels is The Member (1832), another faux-autobiography concerning

Parliamentary politics before the Great Reform Act of that year widened

the franchise. It is a pioneering novel of politics, written from

Galt’s extensive experience of how Parliament actually worked as opposed

to how it presented itself, and foreshadowed what Trollope did in the

Palliser novels in the second half of the nineteenth century.

A man who was such a

master of irony in his novels was the victim of it in his life. He

said that ‘I have ever held literature to be a secondary pursuit’ and

that ‘I have sometimes felt a little shame-faced in thinking myself so

much an author…A mere literary man – an author by profession – stands

but low in my opinion’. He had failed as a businessman and was

unappreciated at the time as a community builder but as a writer of

social realism, psychological insight and high (and low) comedy he has

few equals.

END

See also our page for him

at

http://www.electricscotland.com/history/other/johngalt.htm

|