|

Edited by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Greater Atlanta, GA, USA

Email: jurascot@earthlink.net

Professor Patrick Scott retired a few years

back from the University of South Carolina but if you know Patrick, you

know he has not retired! He works tirelessly as editor of Studies in

Scottish Literature and as a frequent contributor to various Scottish

journals, publications and newsletters like this one. Patrick also

enjoys being grandfather to his three lovely little ones, Virginia,

Scottie and Hadley. He is one of my favorite people and has helped me so

much over the years in building my Burns book collection, among which is

a beautiful and coveted first edition of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish

Dialect. Patrick has supported this site with many articles,

conversations, phone calls and suggestions. Yes, you might say he has

been an inspiration to me and his many words of encouragement throughout

our friendship have kept me above water many times! As Professor Gerard

Carruthers from the University of Glasgow likes to say from time to

time, “He is one of the good people!” Patrick, like Gerry, is one of

only two honorary members of the Burns Club of Atlanta, and it is a

privilege to welcome him back to the pages of Robert Burns Lives!. (FRS:

10.5.2016)

“Not in Egerer"? Roberts Burns in some Early

Anthologies

By Patrick Scott

It continues to surprise me that there is more to

find out about Burns. About a month ago, I was browsing the library catalogue

for early Burns items, and an item came up that I couldn’t remember seeing

before. I checked with Craig Lamont, who confirmed it wasn’t in his draft list

of pre-1802 Burns editions. It wasn’t in Egerer’s long-standard bibliography

either. Burns collectors get a special rush if they discover, or think they’ve

discovered, a Burns item, of any period, that is “Not in Egerer.”

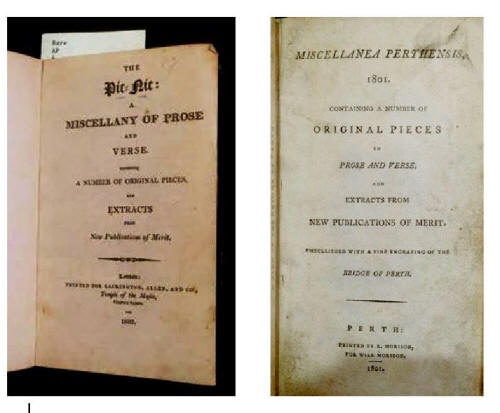

Figs. 1 and 2: Title-pages from The Pic-Nic (London, 1801) and Miscellanea Perthensis

(Perth, 1802) Courtesy of Irvin Department, University of South Carolina

Libraries

The item I’d hit on by accident was an anthology

called The Pic-Nic, published in London in 1802. Pages 86-101 reprinted Burns’s

“The Jolly Beggars” and several other selections from Thomas Stewart’s

recently-published Poems Ascribed to Robert Burns, the Ayrshire Bard (Glasgow,

1801: Egerer 57), together with poems by Edward Rushton and John Skinner.

Several things about it seemed odd. There was no preface, no contents page, and

no mention of the title The Pic-Nic in the page-headers or running titles inside

the book. Then I spotted an imprint on the very last page (p. 218): PERTH /

MORRISON, PRINTER. This led me in turn to R.H. Carnie’s bibliography of Morison

publications, and so on to another item in the Roy Collection (also “Not in

Egerer”), the Miscellanea Perthensis, published in parts but dated on its

title-page “1801.” The two items were identical, except for the first two pages;

as bibliographers say, The Pic-Nic was a variant or remainder second issue of

the Miscellanea, retitled for the London book market. But, despite not being in

Egerer, neither collection was really new to Burnsians. They were listed, and

their connection noted, by Gibson in the 1880s, in the Memorial Catalogue and by

Craibe Angus in the 1890s, and by successive catalogues to the Mitchell Library

collection. Why were they “Not in Egerer”?

Ross Roy used to warn me that Egerer never promised to cover everything. To know

what to expect you have to read the fine print in his preface. Egerer focused on

books, not selections, and his appendix on periodical printings is limited to

the first published appearance of a poem. Anthologies were one of the things he

specifically excluded:

I have tried to include all

the appearances of Burns’s poetical and prose works in all media, except

anthologies and reprints of poems and prose works in periodicals, between

1786 and 1802 (Egerer, p. vii; my italics).

Printing in the 1780s and 1790s was almost as

piratical and entrepreneurial as web-publication is now. Publishers and

newspaper editors had no inhibitions about reprinting whole poems, or even

groups of poems, by so popular a writer, and from the start Burns was fair game

to anthologists. If we want to explore how Burns’s contemporaries first

encountered his poetry, it is worth looking at these unauthorized reprintings as

well as at the authorized or first appearances of Burns’s work.

In principle, anthologies should be easier to trace than chapbooks or

newspapers, because they are books, and so should show up in library catalogues.

But most library cataloguing gives you the title-page information about a book,

and the number of pages, but not much about the contents or even which authors

have been included. In an essay published in 1949, fifteen years before his

bibliography, Egerer himself commented about anthologies that:

it is difficult to know how

often Burns’s poems were printed in these publications, but beginning with

The English Parnassus (London, 1789), and running through to Roach’s

Beauties of the Poets (London, 1795), I have seen some five anthologies with

his productions in them. There are probably more (Egerer, 1949, p. 278).

Unfortunately, Egerer only mentions two anthology

titles out of five, and he doesn’t say what the other three anthologies were. A

further complication is that the second example he chose was a series rather

than a single volume, showing the difficulty of defining what exactly should

count as an anthology. One source that does include anthologies is the Mitchell

Catalogue, though because the relevant section covers all historical periods, it

takes effort to pick out the relatively small number of anthologies published in

the 18th century (Fisher, pp. 86-91). But the Mitchell Catalogue doesn’t include

the first item mentioned in Egerer’s essay, only the second. Several of the

items discussed below are also in Elizabeth Sudduth’s Roy Collection catalogue,

though not in a special section. Further research is worth the effort, because

what the early anthologists chose to print tells you which Burns poems they

thought would resonate with readers.

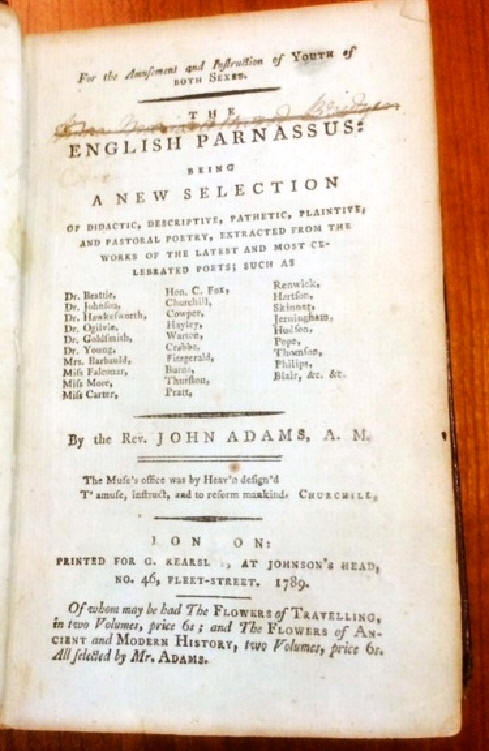

The earliest anthology mentioned in Egerer’s brief comment, which is not listed

by the Mitchell, is The English Parnassus (1789). The copy illustrated here, one

of the most recent acquisitions in the Roy Collection, arrived just last week:

Fig. 3: A recent acquisition: John Adams, ed., The English Parnassus (1789)

Image courtesy of the G. Ross Roy Collection, University of South Carolina

Libraries

It was edited by a clergyman, the Rev. John Adams,

M.A., the schoolmaster of an “academy” in Putney, London. Adams edited several

other similar anthologies, The Flowers of Modern Travels (1788; 3rd edition,

1792), The Flowers of Modern History (1788; 1790; 1796, etc.), and The Flowers

of Ancient History, (1789; 2nd ed., 1790), priced at six shillings a volume,

each twice the price of the Kilmarnock edition.

The English Parnassus provides its readers with a rather grim picture of Burns,

melancholy and religiose, the heir to Robert Blair and the “graveyard School.”

The full title begins For the Amusement and Instruction of Youth of Both

Sexes..., and the title-page carries a quotation from Charles Churchill:

The Muse's office was by

Heav'n design'd

T' amuse, instruct, and to reform mankind.

Burns is among the many poets named on the

title-page, but what follows is perhaps more instruction than amusement. The

Burns poems or extracts (all retitled) are "On the Happiness of an Active Life"

(p. 236; from "Despondency, an Ode," Kinsley I: 232), "Address to the Deity, in

the View [i.e. Prospect] of Dissolution" (p. 237: that is, "A Prayer in Prospect

of Death," Kinsley I: 20), and "On the Influence of Gloomy Weather and Stormy

Weather" (p. 238: from "Winter, A Dirge," Kinsley I: 16). Although all three

items were first published in the Kilmarnock edition in 1786, they would also

have been available to the anthologist in one of the 1787 editions. No one would

claim Adams had selected a good representation of Burns’s work.

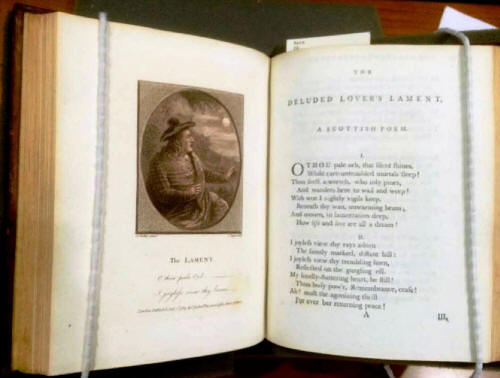

The second example, listed in the Mitchell but not mentioned in Egerer’s essay,

choses a rather different Burns, Burns as formal, rather artificial, 18th

century love poet. This is The Cabinet of Genius, dated on its title-page 1787,

but issued in parts over a period of several years. Burns appeared (with other

poets) in part 34 of the series, and the accompanying engraving carries the date

July 1, 1789. The Cabinet of Genius made a feature of including engravings and

portraits, as well as full-length poems: in fact its selling point was the

illustrations. Each part, bound in blue printed wrappers, cost a shilling, so a

complete set of forty parts, and two supplements, was expensive. The publisher

was the engraver Charles Taylor, but the motivating force was the artist Samuel

Shelley (1756-1808). From Burns, Shelley selected for illustration just one

poem, “The Lament,” again originally published in the Kilmarnock edition. Burns

critics tend perhaps to be over-polite about the poem, because of its

biographical significance for Burns’s relationship with Jean Armour, but however

deep-felt its sentiments, its language is stilted and derivative:

O thou pale Orb, that silent

shines

While care-untroubled mortals sleep!

Thou seest a wretch who inly pines

And wanders here to wait and weep!

.............................................

My fondly-fluttering heart, be still!

Thou busy pow’r, Remembrance, cease!

Ah! Must the agonizing thrill

For ever bar returning Peace?

Although the engraving carries Burns’s own title,

“The Lament,” the poem is retitled in the accompanying printed pages as “The

Deluded Lover’s Lament. A Scottish Poem,” and Shelley’s illustration takes up

the new subtitle by showing a bonneted and plaid-wrapped countryman who somehow

seems too down-to-earth for the poem that he purports to illustrate.

Fig. 4: “The Deluded Lover’s Lament,” from The Cabinet of Genius (1789).

Image courtesy of the G. Ross Roy Collection, University of South Carolina

Libraries

Burns’s name is nowhere to be seen in the number

itself, though he is named plainly enough in the later separate list of contents

for the volume. I don’t know if Ross Roy had never looked for a copy of this

publication for his collection, but he didn’t have one. Fortunately the

publishers rated John Milton as a genius, alongside Burns, so the University of

South Carolina has a nice set in the Robert L. Wickenheiser Collection of John

Milton, and fortunately that copy includes the Burns pages. Within each number,

the poems were separately paginated, to make a mix-and-match series: the preface

to the first volume says that “Gentlemen may bind any numbers together to make a

volume, and in any order they please.” Consequently, there is no guarantee that

a collector who buys a bound set will actually get the Burns item.

With the third anthology, again listed in the Mitchell but not mentioned in

Egerer’s essay, the choice of poems moves closer to what later generations might

think mainstream Burns. Not coincidentally, it is the least pretentious

publication of the three, and was published, if not in Scotland, much nearer to

Scotland than London. Titled A Select Collection of Poems from admired authors,

the anthology was produced by W. Kelley, a local printer in North Shields, on

Tyneside, and its title-page motto is less grimly instructional than Adams’s:

Whate’er the theme, thro’

ev’ry age and clime

Congenial passions meet the according rhyme.

Kelley’s volume includes three Burns poems: “The

Cottar’s Saturday Night” (pp. 139-146); “To a Mouse on turning up her Nest” (pp.

146-148), and “To a Mountain Daisy” (pp. 148-150). Again, all three items go

back to the Kilmarnock volume, but they were all among the poems of Burns that

were immediately popular with reviewers and newspaper editors. Kelley’s was the

first anthology to risk including a poem in Scots, rather than formal Augustan

English. It would seem only justice if his anthology had been the only one of

the first three to reach a second edition. Library cataloguing would suggest so,

for it reappeared in 1801, also as from North Shields, but with a different

printer’s name, T. Appleby. Kelley published only ten titles in North Shields,

all between 1789-1797, so Appleby may have taken over his printing shop. Without

examination, however, it is difficult to tell if this is a genuine new edition

(page-for-page resetting), and so a sign of success, or simply a reissue (a new

title-page on unsold sheets from 1790), in which case it would be a sign that

sales had fallen short of Kelley’s original hopes.

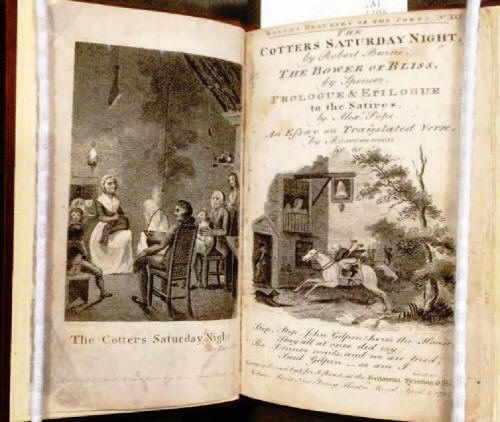

The fourth item, chronologically, would seem to be the second “anthology”

mentioned in Egerer’s essay. Like The Cabinet of Genius, Roach’s Beauties of the

Poets of Great Britain was an illustrated series issued in parts, rather than a

standalone volume. It began publication in 1792. Burns is represented in number

21 (part of volume 6, 1795, in the collected series). Each number had sixty-four

pages, with an engraved title-page and one full-page engraving. The Burns poem

selected for reprinting is again “The Cotter’s Saturday Night” (pp. 53-60). Even

though the other poets featured in the same number included Spenser and Pope,

Burns’s poem heads the list on the part-issue title-page. His poem also provided

the subject for the number’s full page illustration, dated 1795, which depicts

the cotter’s family gathered around a cooking pot hung over a blazing open fire.

Fig. 5: “The Cotter’s Saturday Night,” from Roach’s

Beauties of the Poets, part 21 (1795). Image courtesy of the G. Ross Roy

Collection, University of South Carolina

The discussion for far has looked at just four

examples published in Burns’s life-time, and even those four rest on a fairly

flexible definition of anthology. Egerer’s 1949 essay stated that he had seen

“some five anthologies with [Burns’s] productions in them,” published between

1789 and 1795, that is in Burns’s life-time. What was the fifth? How did he come

up with five? I briefly considered whether he might have been thinking of

William Wilson’s Twelve Original Scotch Songs (1792), which includes Wilson’s

setting of part of Burns’s poem “Hallowe’en,” but if you include one song

collection, you’d have to count others that include Burns text. Johnson started

publication in May 1787, and Thomson in 1793, so that you’d immediately have

more than five.

One solution, I think, may be that in his 1949 essay Egerer was counting as an

anthology another, better-known multi-part publication, Brash and Reid’s Poetry,

Original and Collected. The series is now overwhelmingly associated with Burns

himself, and the engraved title-page to volume 1, printed when the first volume

was completed, is focused on a bust of Burns. Egerer gives the series the full

treatment as a primary Burns publication in his later bibliography (Egerer item

32, pp. 52-55), but it began as a general collection, not simply as poems by

Burns. As Egerer himself points out, only four of the first twenty-four Brash

and Reid numbers included Burns poems. Sandro Jung has recently pointed out that

even the engraved title-page with the bust also makes space for the names of

other Scottish poets (Jung, pp. 137ff.). The motto on the printed title-pages

that follow the engraving varies from volume to volume, but the motto on the

first volume, from Burns’s friend Dr. Blacklock, places the series squarely in

the anthology tradition:

The Muse, by fate’s eternal

plan, design’d

To light, exalt, and harmonize the mind;

To bid kind pity melt, just anger glow,

To kindle joy, or prompt the sighs of wo;

To shake with horror, rack with tender smart,

And touch the finest strings that rend the heart.

Figs. 6 and 7: The two title-pages for Poetry, Original and Selected [vol. 1]

(Glasgow, 1795). Images courtesy of the G. Ross Roy Collection, University of

South Carolina Libraries.

Interestingly, though, the Burns poems that Brash

and Reid chose to include in their first volume are quite different from those

in the four anthologies previously discussed. They start out ambitiously with

“Aloway Kirk” (“Tam o’ Shanter”), in the third number, followed by “The

Soldier’s Return” (no. 4), “John Anderson, my jo” (no. 13), and two items “Here

awa’, there awa’, wandering Willie” and “Behind yon hills where Lugar flows”

(both in no. 23). While the other anthologists had selected items first

published in the Kilmarnock edition, what Brash and Reid reprinted was more

recent Burns material, from more eclectic sources. “Tam o’ Shanter” had been

published first in Francis Grose’s Antiquities of Scotland (1791) and then in

Burns’s Poems in Two Volumes (1793); “The Soldier’s Return” in the first volume

of Thomson’s Select Collection (1793); “John Anderson, my jo” in the third

volume of Johnson’s Scots Musical Museum (1790); “Here awa’, there awa’” again

from Thomson (1793); and “Behind yon hills” in the Edinburgh edition (1787).

But there were in fact Burns poems during his lifetime in other miscellaneous

collections. As R.H. Carnie pointed out, Morison of Perth published regular

“volumes of extracts from contemporary publications ... in a steady steam from

1794 onwards,” later “lumped together under the same of The General Magazine.

There are nineteen volumes in all” (Carnie, pp. 18-19). Each volume cost 2

shillings. In 1795, one of these collections, The Pocket Repository of

Instruction and Entertainment, printed in Perth but also sold in London by

Vernor and Hood, included “A Poem from Grose’s Antiquities,” which was of course

Burns’s “Tam o’ Shanter” (Pocket Repository, pp. 39-45). Burns is not named on

the poem itself, nor in the volume’s contents list, but he is mentioned in the

one-paragraph headnote (p. 38), also taken from Grose. So far, I have not found

any Burns poems in other Morison collections, except those in the Miscellanea

(1801).

In 1949, Egerer was commenting only on anthologies published in Burns’s

lifetime. The same question about the definition of “anthology” continues into

the remaining years for which Egerer otherwise provides full coverage, that is

up to 1802. One further publication series that included a few Burns poems gets

a proper entry in his main bibliography, just like the Brash and Reid

collection. This is The Polyhymnia: being a Collection of Poetry, Original and

Selected, by a Society of Gentlemen (1798-99: Egerer 38), which included in its

eighteenth number what was possibly the first publication of Burns’s “The Bonny

Lass of Ballochmyle” (cf. Kinsley I: 223, under the title “Song. For Miss W.A.”).

The same song was included, the same year, along with Alexander Thomson’s

Sonnets from the Robbers, and Burn’s “Scots wha hae,” in the second of the Gray

Tracts (Edinburgh, 1799: Egerer 37, footnote 7), Because we don’t have an exact

publication date for either Polyhymnia, no. 18, or the Gray Tracts, it is

difficult to determine which came first, but both of them are earlier than the

song’s publication in James Currie’s Burns edition (1800) and in Thomson’s

Select Collection (1801). Paradoxically, though the Polyhymnia might be regarded

as an anthology, another very similar publication cannot. Like Poetry, Original

and Selected, and Polyhymnia, Thomas Stewart’s The Poetical Miscellany (Glasgow

1800; Egerer 49) first appeared as a series of separate pamphlets or chapbooks,

and then as a volume, but despite its title, echoing any number of previous

similarly-titled volumes, it surely fails a basic test for an anthology (of

collecting items from a variety of authors), by making a single author (Burns)

its central justification for publication.

A much less disputable example of an anthology from these later years is another

publication from the north of England, Flowers of Poesy, consisting of Elegies,

Songs, Sonnets, &c. (Carlisle: J. Mitchell, 1798). In addition to the Carlisle

printer, the title-page lists T. N. Longman as selling the book in London; in

this same year, 1798, Longman took over for London distribution another

provincial publication, later to be famous, Wordsworth and Coleridge’s Lyrical

Ballads (Bristol, 1798). Flowers of Poesy included just three items by Burns:

his “Lament for James, Earl of Glencairn” (pp. 12-14); “Man was made to mourn”

(pp. 35-39); and, later in the volume, the song “The Banks of Ayr” (pp. 65-66).

In addition, the editor included “Stanzas to the Memory of Robert Burns, by Mr

Roscoe” (pp. 39-45). In the 1800 edition, Currie included an elegy on Burns by

his Liverpool friend William Roscoe, first published in the Morning Chronicle

that same year, which begins “Rear high, thy bleak majestic hills,” and which

Ross Roy once called “the most frequently-published poem about Burns” (Roy,

“Mair they talk,” p. 54). This second earlier Roscoe elegy, published in 1797

in the Scots Magazine, Edinburgh Magazine, the Monthly Review, and elsewhere,

begins differently, with the first line ”Portentous sigh’d the hollow blast.”

(On Roscoe’s two elegies, see Andrews, pp. 201-205).

Fig. 8: Flowers of Poesy (Carlisle, 1798).

Image courtesy of the G. Ross Roy Collection, University of South Carolina

Libraries.

By 1800 Burns was a standard author, and there must

have been other anthologists who included his work. But the problem of

definition, and so of Egerer’s exclusions, remains. The issues can perhaps be

clarified by returning to the two related volumes, “Not in Egerer,” that started

this exploration: Miscellanea Perthensis (1801) and The Pic-Nic (1802). While

the contents of the two volumes are identical, the Miscellanea Perthensis 1801,

subtitled as containing a number of original pieces in prose and verse, and

extracts from new publications of merit, and with a date in its title, was being

marketed as part of a new series of annuals, perhaps gathering materially

already issued serially. Deciding that Thomas Stewart’s recent Poems ascribed to

Robert Burns, the Ayrshire Bard, not contained in any Edition of his Works,

hitherto published was a “new publication of merit,” Morison reprinted the major

new Burns work, “The Jolly Beggars,” in its entirety, along with eleven other

Burns items, most notably his “Letter to John Goudie,” “Elegy on the Year 1788,”

and “Epitaph on Holy Willie.” Supporting Burns’s own poems were Edward Rushton’s

“Stanzas to the memory of Robert Burns” (discussed in Andrews, pp. 200-201) and

John Skinner’s “Poetical Epistle to Burns.” The Miscellanea was probably issued

serially, because elsewhere in the volume there are letters “To the editor of

the Miscellanea Perthensis,” with dates between March and July 1801. It seems

like yet another of Morison’s repeated unsuccessful attempts to start a

Perth-based literary periodical, to rival those published in Edinburgh (cf.

Carnie, pp. 19-20). Indeed, originally the first page of text was a letter

addressed “To the Editor of the General Magazine,” dated December 6, 1800 (for

which a different item was substituted when the prelims were reprinted). The

Miscellanea was certainly not a conventional anthology, but part of an ongoing

series focused on the opportunistic reuse of attractive, readily-available

material.

The volume’s repackaging for the London market as The Pic-Nic, subtitled A

Miscellany of Prose and Verse, followed by the Miscellanea’s subtitle also, may

be a sign that the periodical originally planned had failed to find subscribers.

It was now being marketed as a stand-alone volume, complete in itself, not as

part of an on-going series. This also was marketing on the cutting edge, for the

new title represented a brand new application of the word pic-nic. It is a full

year later, in 1803, before the Oxford English Dictionary records any example of

“pic-nic” being used in the sense of “something that has multiple contributors

or sources: a miscellany, collection or anthology.” But it’s difficult to

categorize The Pic-Nic, in terms of its new title-page, as anything other than

an anthology.

Egerer’s decision to exclude anthologies from his bibliography, even from the

early years for which he otherwise offered saturation coverage, leaves a fuzzier

border than one might have expected between anthologies and the other formats in

which Burns could be piratically reprinted and successfully marketed. Like

Egerer in his 1949 essay, I am sure that there are more anthologies out there

that I have missed in the discussion above. Similar problems of coverage and

exclusion (and definition) arise with Egerer’s treatment of chapbooks and

newspaper printings, other than first appearances. As Ross Roy warned, the

phrase “Not in Egerer” cannot fairly be applied to kinds of publication he never

promised to cover anyway, but the exclusions still diminish the picture his

bibliography can provide. The big need for the future is to get more

comprehensive listings of all the formats and instances in which Burns was

available to contemporary readers.

References

Adams, the Rev. John, A.M., For the Amusement and Instruction of Youth of Both

Sexes. The English Parnassus: Being a New Selection of Didactic, Descriptive,

Pathetic, Plaintive, and Pastoral Poetry, Extracted from the Works of the Latest

and Most Celebrated Poets (London: Printed for G. Kearsley, No. 46,

Fleet-Street, 1789).

Andrews, Corey E., The Genius of Scotland: the Cultural Production of Robert

Burns, 1785-1834 [SCROLL vol. 24] (Leiden: Brill Rodopi, 2015).

Angus, W. Craibe, The Printed Works of Robert Burns, A Bibliography in Outline

([Glasgow]: privately printed, 1899

The Cabinet of Genius: containing frontispieces and characters adapted to the

most popular poems, &c. with the poems &c. at large, 2 vols. (London: Printed

for C. Taylor, 1787 [-1790]).

Carnie, Robert Hay, Publishing in Perth before 1807 (Dundee: Abertay Historical

Society, 1960).

Egerer, J. W., “Burns and ‘Guid Black Prent’,” in F. W. Hilles, ed., The Age of

Johnson: Essays Presented to Chauncey Brewster Tinker (New Haven: Yale

University Press, 1949), 269-279.

____________, A Bibliography of Robert Burns (Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1964:

Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1965).

Ewing, J. C., Bibliography of Robert Burns, 1759-1796 (Edinburgh: privately

printed, 1909).

__________, Brash and Reid: Booksellers in Glasgow, and their collection of

Poetry, Original and Selected (Glasgow: Robert Maclehose, 1934).

[Fisher, Joe, et al.], Catalogue of the Robert Burns Collection The Mitchell

Library Glasgow (Glasgow: City Libraries and Archives, 1996), esp. pp. 86-91.

Flowers of Poesy, consisting of Elegies, Songs, Sonnets, &c. (Carlisle: Printed

by and for J. Mitchell; and sold by T. N. Longman, Paternoster Row, London,

1798).

[Gibson, James], Bibliography of Robert Burns (Kilmarnock: James M’Kie, 1881).

Jung, Sandro, “Illustrated Glasgow Editions of Robert Burns’s Poems, 1800-1802,”

Scottish Literary Review, 7:1 (Spring/Summer 2015): 133-144.

Memorial Catalogue of the Burns Exhibition held in the Galleries of the Royal

Glasgow Institute of the Fine Arts ... from 15th July till 31st October, 1896

(Glasgow: William Hodge; T. & R. Annan and Sons, 1898)

Miscellanea Perthensis, 1801: containing a number of original pieces in prose

and verse, and extracts from new publications of merit / embellished with a fine

engraving of the Bridge of Perth (Perth: Printed by R. Morison, for Will

Morison, 1801).

The Pic-Nic: A Miscellany of Prose and Verse. Containing a number of original

pieces and extracts from new publications of merit (London: Printed for

Lackington, Allen, and Co., Temple of the Muses, Finsbury Square, 1802).

The Pocket Repository of Instruction and Entertainment. Selected from New

Publications (Perth: Morison; London: sold by Vernor and Hood, 1795).

The Poetical Miscellany; containing posthumous poems, songs, epitaphs and

epigrams (Glasgow: Stewart and Meikle, 1800).

Poetry, Original and Selected (Glasgow: Printed and sold by Brash and Reid

[1795-1798?]).

The Polyhymnia: being a Collection of Poetry, Original and Selected, by a

Society of Gentlemen (Glasgow: J. Murdoch, [1799]).

Roach’s Beauties of the Poets of Great Britain, Carefully Selected and Arranged

from the Works of the Most Admired Authors, 6 vols. (London: Printed by and for

J. Roach, 1793-1795).

Roscoe, William, “Stanzas in Memory of Robert Burns,” Edinburgh Magazine or

Literary Miscellany, new series, 9 (February, 1797), 141-142.

Roy, G. Ross, “Robert Burns and the Brash and Reid Chapbooks of Glasgow,”

Scottish Studies, ed. Joachim Schwend, Susanne Hagemann & Hermann Volkel, 14

(1992), 53-69.

___________, “‘The mair they talk, I’m kend the better’: Poems about Robert

Burns to 1859,” in Kenneth Simpson, ed., Love and Liberty: Robert Burns, A

Bicentenary Celebration (East Linton: Tuckwell, 1997), 53-68.

A Select Collection of Poems from Admired Authors and Scarce Miscellanies. With

many Pieces never before Published (North-Shields: Printed by W. Kelley,

Bookseller; Sold by J. Bew, Paternoster Row, London, 1790).

____________________ (North Shields: T. Appleby, 1801).

Sudduth, Elizabeth, The G. Ross Roy Collection of Robert Burns, An Illustrated

Catalogue (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2009).

Wilson, William, Twelve Original Scotch Songs for the Voice and Harpsichord with

an Accompaniment for the Violin or Flute, Op. Iii (London: Longman and Broderip,

for the Author [1792]).

|