|

the case of the purloined pigs

By

Diane Rapaport

Anyone familiar with Lexington, Massachusetts, has seen the

name Munroe—on the Munroe Tavern, the Munroe Center for the Arts, and

Munroe Road, to cite a few examples. The first Lexington Munroe, then

spelled Munro or Munrow or sometimes just Row, was a Scotsman named

William, who arrived at Boston Harbor with a shipload of other Scottish

war prisoners in 1652. He worked as an indentured servant in Menotomy

(today’s Arlington), earned his freedom, and settled in Cambridge Farms,

as Lexington then was known.

Most of what we know about William Munro—where he bought

land and whom he married and when his children were born—tell us little

about the kind of man he was. But underused old court records still

preserve stories from the lives of people like Munro, often in their own

words. One such file from the Massachusetts Archives, Row v. Bacon,

tells of Munro’s stubborn quest for justice against an arrogant foe. I

call this lawsuit “The Case of the Purloined Pigs.”

The problems started on a Monday in late November 1671,

after a heavy snowfall in a remote corner of Cambridge Farms, near today’s

intersection of Lowell and Woburn Streets. Here, at the house where Munro

lived with his wife Martha and three small children, a neighbor arrived

looking for his hogs.

Michael Bacon (his real name!) had a reputation for letting

his hogs run wild, and this time they had wandered all the way from

Bacon’s house (in present-day Bedford) to enjoy the companionship of

Munro’s own pigs. Munro and his wife, wanting only to be rid of the

uninvited swine guests depleting their meager forage, helped Bacon to

separate his hogs from their own. Bacon then headed off through the woods

with his swine, and the Munros returned to their daily chores.

But Bacon’s hogs apparently did not want to leave their

friends, and they soon came back. This time, when Bacon returned to

retrieve them, he did not bother to sort them out; he just drove off the

whole lot. Seeing most of the family’s worldly wealth hoofing away, Martha

shouted at Bacon to stop, but he ignored her. William, who was occupied

feeding the oxen or fetching firewood, had to drop everything, strap on

snowshoes and take off in pursuit.

Munro was not a man to be trifled with. He had endured many

hardships—on the battlefield, in a prison camp, during the long Atlantic

crossing, and as an indentured servant. Now he was free to farm his own

little piece of land, and those pigs were crucial to his family’s

survival. Hogs meant meat on the table and income to buy other necessities

of life, and Munro could not afford to lose a single animal.

He also knew that Michael Bacon could not be trusted. If

the old court records are any indication, Bacon was known throughout the

county for making trouble. His hogs had damaged crops for miles around,

but he always denied responsibility, blaming others for failing to keep

their fences in repair or claiming that the hogs belonged to someone else.

Bacon’s name appears repeatedly in land disputes, cases of wandering

horses and cattle, slander and forgery accusations, breach of contract,

even a paternity case. Thus, when Munro set off in the snow after Bacon

and his pigs, he had good reason to expect problems.

Munro trudged north through three miles of drifted snow,

following hog tracks until he finally overtook Bacon and found most of his

livestock. One pregnant sow was "so tired and spent that shee could not

come back," and he had to leave her with Bacon. Another sow, also "big

with pig," was missing. Munro was angry, but nothing more could be done

before nightfall. He drove the rest of his hogs back home.

The next day, Munro sought out constable’s deputy John

Gleison and his brother William. He showed them the hoof‑trodden farmyard

and the path through the woods, and together they trekked back to Bacon’s

house to retrieve the last two swine. Bacon’s response was predictable.

First he pretended the incident never happened. Then, when the Gleisons

clearly were not accepting that story, he “confessed that William Rows

swine was with him in the drift the day before, but...he did them no

wrong,” and he had none of them “in his hands” now. “If Row lost them, he

must go look for them.” Bacon, of course, did not offer to help.

On Wednesday, the weary Munro turned to his neighbors John

and Benjamin Russell, and together they scoured the woods for the missing

hogs. They found one, stuck in a drift, amazingly still alive, and with

"much difficulty" they brought her home.

One sow was still missing, and Munro’s patience was running

out. He took the law‑abiding next step, which required yet another long

journey on foot through the snow. He walked to Cambridge, to magistrate

Thomas Danforth’s house overlooking Harvard College, where he filed a

claim against Bacon. The amount in controversy was small enough that the

magistrate could resolve the dispute without resort to the courts.

Danforth took up quill pen to issue a warrant, ordering Michael Bacon "to

appeare before me at my house, the last day of the weeke at 12. of the

clock to answear the complaint of William Row, for violence done him in

taking away his swine out of his yard, & driving them away...."

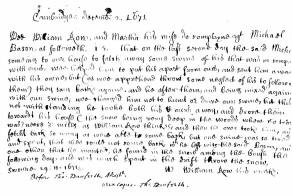

Complaint

of "William Row and Martha his wife" against Michael Bacon, December 2,

1671,

as recorded by Cambridge magistrate Thomas Danforth. Courtesy of Supreme

Judicial Court of Massachusetts, Division of Archives and Records

Preservation."

At the appointed time, six people—William and Martha Munro,

the Russells, and the Gleison brothers—crowded into the magistrate’s study

to testify. Danforth recorded the evidence with careful penmanship, and

the witnesses all signed with their marks. Michael Bacon was not there and

he lost the case. The constable’s deputy set out to seize a "branded

steere" from Bacon to ensure payment of Munro’s damages.

Shortly thereafter, before Munro could collect a single

shilling, his missing sow reappeared at his door. She was “lamed and went

but upon three legs,” delivered by a man who claimed that he "found" her

and was asked by Bacon to bring her home.

Bacon probably hoped that returning the sow would get him

off the hook for damages, but Munro stood firm. In late December, Bacon

asked for a rehearing, which Danforth granted on January 29. The result

was the same, only now Bacon owed more, reflecting the added costs for

witness time and constable’s fees.

Still Bacon refused to pay, and he mounted a vigorous

appeal, seeking a jury trial in the Middlesex County Court. He hired

Concord lawyer John Hoare to draft a tedious petition with a long series

of technical arguments, from improper service of the attachment on his

steer to misfeasance by the well‑respected Danforth. The trial took place

in Cambridge on April 2, 1672, probably at the local Blue Anchor Tavern

(as was customary in those days, since only Boston had courtroom

facilities). Someone apparently represented Munro at the trial (although

his identity is not known), for an elegantly‑written legal argument

appeared in the court records on Munro’s behalf.

The final result, after more than four months of legal

wrangling, was judgment again in favor of Munro: “One Pound sixteen

shillings & foure pence,” plus court costs, a goodly sum, but probably

less a financial boost than a moral victory for the dogged Scotsman.

Presumably Bacon paid up, for here the paper trail of Row v. Bacon

ends. Munro returned to a quiet farming life, but Bacon continued to keep

the courts busy in disputes with other neighbors. Anyone who thinks that

the “litigation explosion” is a modern phenomenon should read the

seventeenth-century court records!

Diane

Rapaport is a former trial lawyer who has made a new career as a writer,

historian and genealogist. One of her special interests is the

little-known story of Scottish war prisoners exiled to the American

colonies in the mid 1600s. She has spent years tracing the fate of these

Scotsmen, and her articles have appeared in

New England Ancestors,

The Highlander,

History Scotland

and other publications. Her e-mail

address is

rapaports@aol.com. Diane

Rapaport is a former trial lawyer who has made a new career as a writer,

historian and genealogist. One of her special interests is the

little-known story of Scottish war prisoners exiled to the American

colonies in the mid 1600s. She has spent years tracing the fate of these

Scotsmen, and her articles have appeared in

New England Ancestors,

The Highlander,

History Scotland

and other publications. Her e-mail

address is

rapaports@aol.com.

© 2002 Diane Rapaport -

all rights reserved

Note:

This article appeared in the Winter 2004 issue of

New England Ancestors

magazine and is reprinted by permission of the New England Historic

Genealogical Society. (See Diane Rapaport, New England

Ancestors 5 (Winter 2004): 54-55.) For more information about New

England Ancestors and the New England Historic Genealogical Society,

please visit

www.NewEnglandAncestors.org. |