|

When God first made the world, He looked at the bare and barren

hillsides and thought how nice it would be to cover them with some kind of beautiful tree or flower. So he turned to the

Giant Oak, the biggest and strongest of all of the trees he had made, and asked

him if he would be willing to go up to the bare hills to help make them look more

attractive. But the oak explained that he needed a good depth of soil in order

to grow and that the hillsides would be far too rocky for him to take root.

So God left the oak tree and turned to the

honeysuckle with its lovely yellow flower and beautiful sweet

fragrance. He asked the honeysuckle if she would care to grow on the hillsides and spread her beauty and fragrance

amongst the barren slopes. But the honeysuckle explained that

she needed a wall or a fence or even another plant to grow

against, and for that reason, it would be quite impossible for

her to grow in the hills.

So God then turned to one of the sweetest and most

beautiful of all the flowers - the rose. God asked the rose if she would care to

grace the rugged highlands with her splendour. But the rose explained that the wind and

the rain and the cold on the hills would destroy her, and so she would

not be able to grow on the hills.

Disappointed with the oak, the honeysuckle and the rose,

God turned away. At length, he came across a small, low lying,

green shrub with a flower of tiny petals -some

purple and some white. It was a heather.

God asked the heather the same question that he’d asked the

others. "Will you go and grow upon the hillsides to make

them more beautiful?"

The heather thought about the poor soil, the wind and the

rain - and

wasn’t very sure that she could do a good job. But turning to God she replied that if he wanted her to

do it, she would certainly give it a try.

God was very pleased.

He was so pleased in fact that he decided to give the heather some

gifts as a reward for her willingness to do as he had asked.

Firstly he gave her the strength of the oak tree

- the bark of the heather is the strongest of any

tree or shrub in the whole world.

Next he gave her the fragrance of the honeysuckle

- a fragrance which is frequently used to gently

perfume soaps and potpouris.

Finally he gave her the sweetness of the rose

- so much so that heather is one of the bees

favourite flowers. And to this day, heather is renowned especially for

these three God given gifts.

Introduction

Heather,

the name most commonly used for this plant, is of Scottish origin,

presumably derived from the Scots word HAEDDRE. Haeddre has been

recorded as far back as the fourteenth century, and it is this word

which seems always to have been associated with ericaceous plants. Heather,

the name most commonly used for this plant, is of Scottish origin,

presumably derived from the Scots word HAEDDRE. Haeddre has been

recorded as far back as the fourteenth century, and it is this word

which seems always to have been associated with ericaceous plants.

The origination however is obscure, and

the variations are many. Hader is found in Old Scottish from 1399,

heddir from 1410, hathar from 1597 (although this form of the word may

also be seen in place names dating back to 1094) and finally heather

from 1584.

The botanical name for the Heath family

is Ericaceae, which is derived from the Greek 'Ereike’, meaning

heather or heath. The name is generally, and more properly reserved for

the most widespread of the Heath family Calluna vulgaris, (Calluna from

the Greek ‘Kallune’ - to clean or

brush as the twigs were used for making brooms and vulgaris from Latin,

meaning common.)

However the plant is sometimes also

referred to as Ling - derived either from the old Norse ‘Lyng’ or

from the Anglo Saxon ‘Lig’ meaning fire and referring to use as a

fuel.

Whatever the exact origin, one thing is

certain. Heather moors cover a vast amount of Scottish countryside. With

approximately 2 to 3 million acres of Heather Moors in the East and only

slightly fewer in the South and West, Heather is without doubt one of

Scotland’s most prolific and abundant plants.

A Plant in Abundance

There are a number of reasons why

heathers are so abundant with such a wide distribution. Firstly, the

plant’s reproductive capacity is high with seeds produced in very

large numbers.

Each tiny heather flower has 30 seeds, so

it is quite possible for one large plant to produce up to 150,000 seeds

per season. Small and light, the seeds are readily dispersed by wind and

insects, with the germination period lasting up to six months. This long

period is advantageous to the heather as it means there will be reserve

seedlings to take over if the first seedlings should fail.

Soils

Most heather seeds are normally shed

during November and December, with germination proving most successful

on soils with a pH of between 4.5 and 7.5 (although it is better on

soils tending to the lower end of this scale). But Heather is a very

versatile plant. It readily adapts and thrives in soils which are not

only acid, but also those which are poorly supplied with the mineral

elements normally essential to plant growth. Heather can survive in many

soil types, from those which are peaty with a high water content to

those which are free draining and relatively dry.

Grazing

Despite repeated grazing, heather is

relatively resistant to feeding cattle and sheep. With reserve buds

readily replacing those which have been cut back by the animals, this

hardy plant is really only damaged and destroyed when grazing becomes

excessive.

The hardiness of heather is demonstrated

by its ability to flourish despite recorded temperature extremes. At

ground level, temperatures have been recorded in Strathspey as low as

-32°C (-18°F) in winter and as high as 38°C (100°F) in summer.

Life expectancy of heather is approx.

40-50 years.

Heather Burning & Regeneration

One of the most common and effective ways

of managing heather clad land is the age old method of burning. Heather

burning or ‘Muirburn’, as it is called in Scotland, was, and indeed

still is, necessary for a variety of different reasons.

Originally the process was used not only

to prevent tall shrubs and trees taking over the moor - limiting the

number of older Heather plants which were tall and woody with few young

shoots. But it was also used to create open spaces of land which made it

difficult for preying wolves and foxes to approach domestic herds

unseen.

Now however, heather burning is primarily

used to create the conditions necessary for uniform regeneration of

young heather plants - encouraging high reproductivity of edible new

shoots which are essential to animals and birds dependant upon heather

for survival. Grouse shooting employs many people and brings in valuable

revenue in sparsely populated areas of Scotland.

Burning, as you might expect, is

restricted by law.

In order to cause as little disruption

and damage as possible to both nests and wildlife, the period for

burning in Scotland currently begins in October and lasts until 15th

April. Traditionally however most burning is carried out in Spring,

although some estates maintain that regeneration is better after burning

in the autumn. A saying from North Uist, which has been passed down

through generations, refers to the heather burning which had to be done

in a bad season;

‘Is fearr deathach a’ fhraoich, na

gaoth a reodhaidh’

(Better is the smoke of the heather

than the wind of the frost.)

After burning almost all of the above

ground parts are destroyed. But reserve buds at the base of the stems,

which have been shielded by earth and moss, are protected from the heat

and give rise to new growth the following season. This is known as

vegetative regeneration, with the new growth, referred to in Gaelic as

Mionaa (Meanbh) Fhraoch.

However, this is not the only

regenerative process. Another, although somewhat slower way, is by seed.

Germination of heather seed occurs in the gaps between the burnt plants

- usually where there is a moist seed bed and fluctuating temperatures.

Heather in the Food Chain

Domestic and Wild Animals.

Although few

animals rely on just one food source, many depend

significantly on heather for survival. - Red Deer, Rabbits and Hares, to

name but a few. And it is the heather’s young shoots with which most

of these animals supplement their diet.

One look at a typical example of a food

chain shows just how important heather is in the cycle of moorland life.

Heather shoots.. eaten by caterpillars..

in turn eaten by Meadow Pipit.. preyed upon by Hen Harrier.

At their best, the shoots provide

important minerals such as calcium, phosphorus, nitrogen, magnesium and

potassium, with their nutritional quality determined by the particular

soil quality in that area.

The shoots may be grazed throughout the

year. In winter, the green shoots are eaten followed by the new green

shoots in May. In summer the flowers are eaten, in bud and bloom, along

with the seed heads. And in autumn, even the seed capsules help to

sustain wildlife on the moor.

The Red Deer browse heavily on the

heather, particularly in the winter months when other food is hard to

find. The Roe Deer also graze on the plant, preferring to stay in the

longer heather. Even the Reindeer which were introduced into the

Cairngorm area in the 1950’s, have also come to rely on this popular

food source. Other ‘nibblers’ include Mountain and Brown Hares who

require the young heather for browsing, and rank heather for cover.

Rabbits living on moorland also enjoy young shoots.

According to the Scots National

Dictionary the Wild Cat was also referred to as the Heather Cat.

Of course domestic animals too, such as

cattle and sheep, also benefit from grazing on heather - in areas which

have been specially designated and managed solely for this purpose.

Cattle use the heather to supplement

their winter diet of hay, turnips and manufactured foods. ‘Teck' is

the name used in Shetland to describe the long heather which was used as

fodder. However it is perhaps, the hardiest of domestic breeds which is

the main beneficiary - the Blackface sheep. For many years to the

present day, sheep farmers have taken their sheep to the heather to give

the resultant lamb ‘that special flavour’. Indeed the Blackface

Sheep Breeders Association is pushing hard to have the pure-bred ‘Blackface

Lamb from the Heather', officially recognised as one of Scotland’s

gourmet tastes, comparable with grouse, venison, whisky and salmon.

There are, however, drawbacks as the

following extracts from "The Scots National Dictionary"

outline: Heather Blindness — a disease of sheep.

Contagious opthalmia is a specific

disease of sheep that is common to most sheep-raising countries,

including Scotland, where it is often referred to as "heather

blindness".

Heather Cling - a disease

prevalent among sheep that have been grazing too long on heather.

Heather Claw - A dog’s dew claw,

which is apt to catch in heather with resulting pain, and is therefore

often cut off.

Heather Clout - Also in reduced

form Clu.

The fettock, joint or ankle, the external

and posterior part of which is protected by two horny substances, which

we call heather-clouts.

A Natural Habitat for Birds

The bird most associated with heather is

the Red Grouse, sometimes referred to as ‘The Heather Bird’. The

Gaelic term for the male bird is Coilech-Fraoch, the Heather Cock, with

the female equivalent being Cearc-Fraoch, Heather Hen.

Apart from nesting time when the bird

feeds primarily on insects and grubs, the Grouse will feed on young

heather shoots. Using grit to grind up the hard fibrous heather in it’s

gizzards, the bird is able to turn much of the lignin and cellulose,

(the woody part of the plant), into usable energy. So even in heavy

snows when the heather can still be seen sticking up through the icy

cover, there will be no lack of energy to maintain life. Indeed, this is

why grouse are seldom found starving during deep snows.

Breeding tends to be more successful on

more nutritious heather.

Of course, Heather is more than just a

food source. Heather is also a natural habitat for the hundreds of

different insects, animals and birds all of whom are inter-dependent on

one another.

Providing nesting sites, shelter and

protective cover from predators there are many different types of bird

to be found thriving on the moor.

Red Grouse: Relies on heather not just

for food but also as a protective cover from predators such as the

Golden Eagle and Peregrine Falcon. In Caithness, it is common to see

bunches of heather tied to the top of deer fences which warn these and

other low-flying birds, to take evasive action!

Black Grouse: The best stocks of this

bird are to be found on a moor with a mixture of scrub, tall heather,

bogs, shorter vegetation and farmland. The hen chooses thick heather for

her nest and then moves her chicks to damp ground with rushes, tall

heather, bog myrtle and scrub. Known as the Heather Cock, this bird

consumes the Heather Beetle in great quantity.

Ptarmigan: This bird is normally found on

higher slopes, but in severe winters it will come downhill in search of

the young shoots.

Capercaillie: The Turkey Sized

Capercaillie uses pieces of heather or pine needles to cover its eggs

until its clutch is complete.

Golden Plover: This bird with its

beautiful, plaintive cry nests in the short heather.

Dotterel: Like the Golden Plover and a

member of the Plover family, this bird makes its nest on a carpet of

prostrate heather, high in the Cairngorms.

Lapwing: Sometimes referred to as Peewit

or Green Plover, this bird can be found in short heather close to the

grassland of nearby crofts and farms.

Curlew: For me, Spring has arrived when

the beautiful bubbling calls of this bird can be heard as it glides back

from wintering at the coast to its nesting site in the long heather.

The Common Snipe: Sometimes referred to

as the Heather Bleat(er), gets its name from the sound made by the male

with its tail feathers in flight - mainly during courtship.

Ring Ouzel: Known as the ‘Heather

Blackie’, this bird is very much the ‘Mountain Blackbird’ and

makes its nest from coarse grasses, heather and mud.

The Meadow Pipit: Also known as the

Heather-Cheeper.

The Heather Lintie: Also referred to as

the Twite or Mountain Linnet breeds on the moors and open ground.

The Heather Peeper: Another name for the

Common Sandpiper.

The Heather-Cun-Dunk: A sea bird, either

the Goosander or the Northern Diver.

Golden Eagle: this magnificent bird

constructs its nest, or eyrie, from twigs of heather and preys on

moorland creatures such as Red Grouse and Mountain Hares.

Other birds of prey which are associated

with the heath include the Buzzard, Peregrine Falcon, the Merlin, Hen

Harrier and Short Eared Owl.

Insects

Heathers are affected relatively little

by pests. However there are certain types of insects which can be found

living on the plant. These include the Heather Gall Midge (Wachtiella

ericina) and the Heather Beetle (Lochmaea suturalis).

Other types of insect to live on the

heather are the Sap Suckers. One such example is the Froghopper,

sometimes referred to as the Spittlebug, because of the froth of bubbles

with which it surrounds itself. These bubbles are created from the sap

of the heather plant and are a familiar sight to many people.

The Emperor Moth is a caterpillar which

feeds on the young shoots. It is camouflaged magnificently with its

green body taking on the exact colour of the heather, whilst the pimples

on its body resemble the colour of the heather flower.

The adult moth has tremendous ‘eyes’

which help to ward off prey as it flies over the heather throughout

April and May. After mating the female flies by night to lay olive-brown

eggs on the heather.

The Northern Eggar Moth is another

caterpillar which is also common on heather moors. feeding, once again,

on the young shoots.

In Banffshire, the Dragon-Fly is better

known as the Heather Bill.

Reptiles

There are a few reptiles to be found

living amongst the heather It is not unusual to see Adders basking in

the sun on hummocks before slithering off to hunt for toads and frogs in

nearby pools. In Caithness, frog tadpoles are called Heather-fish.

Associated Plants

On well drained areas Calluna is

generally accompanied by Erica cinerea (Bell Heather), Tormentil and

Common Milkwort. While on wetter soils, Bell Heather is replaced by

Erica tetralix (Cross-leaved Heath) accompanied by other plants such as

Bog Asphodel and Sundew.

In open pine woods, where the ground

vegetation is heathy in nature with plants such as bilberry, cowberry

and crowberry, and grasses like wavy haired grass and soft grass,

heather is once again a prominent member of the plant community. Even in

the Birch woods where the canopy is light, this versatile plant is not

hindered in its growth and is surrounded with bracken and bilberry.

Carline Heather: The bell heather of

Erica tetralix and Erica cinerea. Used also to describe French Heather,

Fraoch Frangach, by old Perthshire hill-folk.

Cat Heather: This is a name used to

describe various types of heather including Erica cinerea, Erica

tetralix, or Calluna vulgaris.

Dog Heather: This is the Aberdeenshire

name given to the ling heather.

Heather in the Construction of and

Thatching of the Dwelling Place

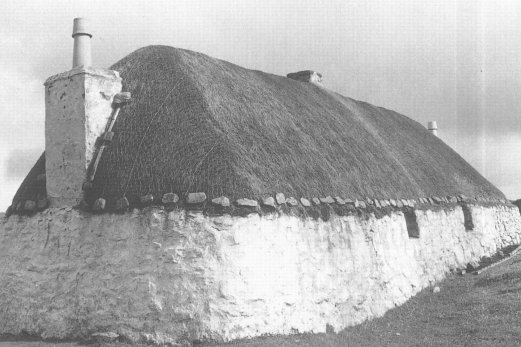

Heather thatch on house in Sidinish, North

Uist.

As one

of the most common and readily available resources in the countryside,

Heather has always played an important role in the traditional

construction of buildings, particularly in areas such as the Hebridean

Islands where construction was strictly determined by the availability

of natural materials and their proximity to the proposed site. As a

result, heather was used to build many dwelling houses, churches and

farmhouses. From walls and thatching to the ropes and pegs which

actually held the building together, Heather proves its versatility once

again.

Thatching with Heather was carried out in

areas as far apart as Shetland in the North and the Island of Arran in

the South West. Buildings which were Heather Theekit - (thatched with

Heather), were generally a better class than those which were thatched

with straw. The old Blackhouses of Lewis for instance which were

thatched with straw and constructed without a chimney or smoke hole, so

as to impregnate the straw with soot for future use as a fertilizer in

the fields were, despite being the possible forerunners of our present

day recycling philosophy, unpopular as they had to be replaced annually.

A Heather roof however, according to J.

Smith in the ‘General View of Agriculture of Argyll (1798), will last

100 years. He tells us that, "Heather roofs are more suited to

Farmhouses, as they, along with our ordinary timber, can be had for a

trifle, last almost as long as slates and give less trouble in

repairs.... It is astonishing that, in a country in which Heather

abounds, these roofs are not more common. They are indeed heavier than

straw roofs; but by making them a little steeper, and placing the

couples a little nearer than ordinary roofs, most of the weight will be

thrown on the walls, which, if made as they ought to be, of stone and

lime, will not feel the burden. It makes a neat warm and durable

roof."

The thatching of these roofs was done by

a ‘heatherer’ and various methods of construction have been

recorded. One method however, which was perhaps in most common use was

to make a covering of divots (thin sods pared off by a spade made

specifically for that purpose) above the wooden framework. Over that was

then spread a thin coat of thatch which was then fastened down by straw

or heather ropes, crossed through each other in a net-like fashion, and

with stones suspended.

Heather divots would frequently be used

to cover the crofters byre and stable roofs and quite often the

crofter's own cottages too. But most often, they were used for covering

potato and turnip pits in winter. The divots were clean and warm, and at

the same time, provided better ventilation than grass sods. Using the

heather divots in this way, laid on like slates, heather side down,

there was no danger of the crops sweating and rotting.

The heather-thatched shielings of Glen

Lyon between 1837 and 1841, were described by Duncan Campbell in his

book, ‘Reminices of an Octogenarian Highlander', as not much to look

at on the outside, but rather substantial and roomy on the inside. Built

of stone, thatched with heather and well constructed for dairy purposes,

recesses, or rather cupboards, were built into the thick walls with

flags for shelves on which milk vessels were placed. Planks were placed

at intervals across the building from one top of the side wall to the

other. And it was here that the cheeses, partly taken out of their

presses, were placed to harden and become partially smoked with the reek

of the peats and the remains of the heather stalks which had been burnt

to the ground the year before.

In ancient times, Churches too were

generally thatched with heather.

The roots of heather served as effective

nails and pegs - used especially for hanging slates. But it was the

small twigs of heather, trimmed and shaped with a knife which were used

to peg down the heather divots in the thatch. Once pegged down, a thick

fringe of heather was arranged to project under the lowest layer of

divots in order to carry rainwater drips away from the roof, clear of

the walls. If however the house did let in water, fesgar, a facing of

straw or heather, would be fastened with boards around the outside of

the house. (Fesgar is also referred to as a strengthening rim for straw

or heather baskets.)

Walls were constructed of Heather-An-Dub

(Heather and daub, sometimes spelt dab) which was a combination of

heather with mud or clay. Built with an inner and outer skin of stone,

the walls had a central core of heather divots. There were many types of

resulting buildings. Basket Houses for instance on the island of Mull

were constructed by wattling together heather and branches of wood. And

in Strathspey, it has been recorded that heather brushwood was used (in

conjunction with wild juniper) in cavity walls of houses to act as

insulation and soundproofing. And talking of insulation, it has also

been used by hill people as insulation against the cold by packing it

down trousers and inside jumpers!!!

ROPES AND LADDER: The Skara Brae

excavation in Orkney revealed a prehistoric village dating back to

around 2000BC. Amongst primitive tools and animal bones they discovered

Seomain fraoich - Heather rope.

Seomain fraoich was made from long stems

of the Heather plant, pulled and woven by hand, and used for a variety

of purposes - from holding down thatch to securing fishing boats. It was

even used in Harris to gather in the seaweed for the production of kelp

which, in turn, yielded iodine essential to the manufacture of glass.

In the Helmsdale area ladders made from

heather ropes, bound together and swung over the cliffs, were used to

give direct access to the shore.

Inside The Home

Even to the present day, crofters and

farmers rely upon heather as an abundant and efficient fuel for their

fires - with the part which is most generally burnt coming from the top

layer of the peat bog. Once cut, stacked and dried it was used for

heating the dwelling place, cooking, drying (especially for drying corn

before it went to the mill), brewing and baking. The small heather stems

were also used as they were found to make excellent ‘kindlers’ for

starting the fire. The crofters even found a use for ‘Heather Birns’

burnt heather - using the short, charred stalks of the plant as writing

instruments!

The Skara Brae excavation in Orkney

revealed evidence of beds in the form of stone boxes, lined with either

heather or straw and dating as far back as 2000 BC. The original heather

beds!

Obviously these beds were developed over

the years with crofters gradually perfecting their construction

techniques using only the longest, straightest and finest stalks of the

young heath. These stalks would be pulled at their highest in bloom and

fragrance, with as little root as possible. Once they had been left to

dry for a few hours to evaporate any dew or accidental moisture, they

would be placed together as thickly and closely as possible, with their

tops arranged uppermost. Inclining a little towards the head of the bed

- which was generally against a wall, the stalks would be held together

at the sides and foot of the bed by logs of wood which had been cut to

appropriate lengths.

Even an outdoor heather bed has its

merits!

And just in case you were wondering about

the support afforded by a heather bed, you might be interested to note

that, according to Mr R. Oldale, Kilchrenan, Argyll, the anvils below

the huge drop hammers in the Sheffield Steel forges were sited on beds

of heather. These heather beds were apparently sufficiently well

cushioned so as to absorb the tremendous impact delivered by the hammers

and thus prevented the anvils from fracturing!

Inside the croft, heather had many

practical uses - from baskets and brushes to pot scrubbers and doormats.

Thanks to Bob at Brooms; Brushes and

Sundries at www.besombinder.com

for the above old picture of a Scotsman selling Heather Brooms.

Heather brooms were made from the long

heather stems which were gathered in spring when they were at their most

pliable. These would then be bunched together and guilloteened to form a

trim broom.

Many types of besoms and brooms were made

in this way, and the art of brush making became a small, rural craft

industry. Types of brushes and besoms varied, depending on locality, and

were sold roundabouts by Heather Jennys and Heather Jocks (the nicknames

for the men and women who sold heather goods). Indeed a great trade was

long practised in the making of heather goods as, until around 1860,

there were few modern brushes to be found on an ordinary farm.

A Curing Heather Cow was the term used to

descibe a broom made of heather twigs whilst a Heather Range(r)/ Reenge

- sometimes referred to in Orkney as a Heather Scratter -was the name

given to a bunch of straight heather stems cut to equal lengths and

bound firmly together for use as a pot scrubber or for brushing the flue

of a chimney. In-fact, to this day, Chimney Cleaners in Lewis still use

bunches of heather tied to to the end of ropes as they insist that it is

the only way to get the job done properly.

Heather doormats were also common in the

croft. Mats would be specially made for the kitchen using long, thin

heather stems. They would be woven in many different patterns with the

bottom side rough where the clipped ends were concealed and the upper

side smooth. In Islay, these mats which were woven from young heather

were known as ‘peallagan’.

Baskets were made all over the highlands

and had many uses round the croft. Using long heather stems, they were

made either to be carried on the human back or as pack saddles which

were carried by horses. They were also hung on walls for storage. The

Saalt (Salt) cuddle from Shetland, is just one example of such a basket

which was hung beside the fire and used to keep salt dry.

Of course there were many other different

types of basket each with a specific role. The Mudag (Wool Basket) for

instance, was specially made to hold wool before carding, and the Maisie

- a large meshed panier of bent rope or heather, was used for carrying

sheaves and peats.

In Orkney, one particular form of basket

was called a ‘Heather Cubby'. These baskets were made in various forms

but the most common one was woven from long, fine, straight heather

stalks, not rough or crinkly, and was used for carrying turnips from the

shed to the byre for the cattle. Carried on the back, they were also

used to bring peats inside from the stack. Another type of basket was

the ‘Sea Cubby’ - so called because it was specially used to carry

home fish. Other baskets including the Heather Caissie (from Orkney) and

the Heather Wuddie/Widdie were made to hold fish, fishing line and bait.

Even the lobsters of the Hebrides which were sent to London where they

were in great demand, travelled packed in heather.

Examples of these and other utensils can

all be seen at the Highland Folk Museum at Kingussie.

Uses of Heather Outdoors

Abundant and readily available, heather,

with its twiggy nature and durable characteristics - even in bog

conditions, was often used in the making of roads, tracks and footpaths.

It was mainly laid as an intermediate layer between a base of brushwood

and a surface of gravel. And it was this method, which was reportedly

used, in laying tracks across Rannoch moor.

In Mediaeval times, the otherwise useless

parts of a sheep’s fleece, known as ‘daggings’, were laid and

mixed with heather to form footpaths across the heath. This ancient

practice is currently experiencing a revival, with daggings by the

hundred-weight being airlifted by the RAF to reinforce foundations along

the popular walkways of the Cairngorms.

Depending on the drainage, lighter soils

can be prone to ‘silt up’. To avoid this happening, the tops of old

heather would be placed in the bottom of a trench to act as a field

drain. Another way in which heather was useful as a ‘conservation

method’ was in the production of stabilising banks. These banks, in

conjunction with planting marram grass, would be made from long heather

twigs and used to stabilise dunes - a method employed, particularly in Holland. Used for protecting sheep

and other animals in the winter months, sectioning them off into

particular areas, fences would be made from the longest, most supple

stems of rank heather, intertwined between stakes and posts.

Heather branches were very often used to make walking sticks,

particularly in Colonsay where the rich peaty soil on the east of the

island made ideal growing conditions. Two such specimens were sent to

Edinburgh University. One branch was measured at 6ft. whilst the other

was a mere 4ft. in height!

Salmon Fishing

Heather was often burned as a fuel for cooking and heating. But it

was also used for lighting - Salmon

Lighting that is. The following extract from ‘Days and Nights of

Salmon Fishing in the Tweed’ by William Scrope, descibes how heather

was used in an age old technique for catching salmon.

"We went to the barn and tied up twae heather lights frae a

bunch or twae which I had gead the miller lad to dry in the kiln ten

days before. They may talk o’ ruffles and birk bark baith, but gie me

a good heather light, weel dried on the kiln for a throat o’ the Queed."

Bunches of heather which had been thoroughly dried were placed inside

a special basket-like carrying device. Once set

alight, this ‘heather torch’ would be held at the water’s edge

where the flickering flames and lights would attract the fish from the

low water, (known as ‘burning the water’). The salmon would approach

the lights, whereupon they would be speared by a five barbed, long

handled fork, called a "leister". This method of fishing was

legal at the time.

Raising the Sails

A story, taken from a book by John Mowat,

tells of another rather ingenious way in which heather was used by James

Bremmner - a famous ship builder and harbour engineer who was born in

the Parish of Wick in 1784.

"The brig Isabella of Sunderland was

driven on the sands of Dunnet in a storm, and was held fast in the quick

sand. Trenches were dug with a view to floating her, but every becoming

tide refilled them. Mr Bremmner was a little puzzled and, turning to his

foreman said, "John have ye no plan?"

On receiving an answer to the negative,

he sharply replied, "Then awa to the hill and poo heather!"

Not knowing to what purpose this was meant, the man quietly submitted

and was soon reinforced by a number of women and children from the

neighbourhood, organised for the same purpose. On the tide receding, he

built up the sides of the trenches with the heather, a plan which

effectually prevented them from filling in again. Anchors were put out

astern and as the tide flowed, he summoned the whole neighbourhood to

pull the vessel off with tackles. The Isabella soon slipped into the

water"

From Floor Tiles to Jewellery

Shortly after the second World War, a

restriction on the use of wood was initiated. Ground level houses were

unable to have the normal timber floor boards and were mainly

constructed of concrete or stone. But these floors were hard and cold

underfoot, and they had no ‘give’. So, in answer to this problem, a

small factory employing three to four people, was set up at the side of

Loch Lomond, in Dumbartonshire. The factory then set about the

production of floor tiles made from the woody heather stem. The

resultant tiles were extremely hard wearing and lasted a good length of

time.

The tiles were made by compressing the

heather stems together into blocks using a special bonding agent. Then

they were cut transversely, producing the resultant floor tile.

When eventually restrictions on the use

of timber were relaxed, and normal building techniques resumed,

production of the heather floor began to dwindle as it proved too

expensive to produce.

However the basic technique which had

been developed by this small factory of compressing the heather stems

was essentially a good one, and was put to a more cost effective use by

the jewellery industry.

Initially small blocks were recessed into

wood and staghorn to form brooches and pendants. Then a method of dying

the stems was developed which resulted in more colourful and interesting

jewellery. In time, the small craft workshop became more and more

sophisticated in techniques, design, production and marketing.

Paint Colourings and Dyes

Born in 1772, Dugald Carmichael, a

little-known botanist returned to his native Scotland after a lifetime

of exploring the world in search of new plants. Dugald’s other great

love, besides botany, was painting. But he had great difficulty finding

the exact colours he required, so he started to use the natural pigments from plants to

colour his paints. And it was to the tops of the heath that he turned to

for the colour yellow.

Of course the art of using natural pigments for colouring has been

around for centuries with crofters relying on the heather to dye their

wool and cloth.

A Traditional Recipe for the Dying

of Wool

Gather the tops of the (Barr An Fhraoich) Heather. Gather when they

are young and green, and growing in a shady place. Place a layer of wool

and heather alternately on the bottom of the pot until the pot is

filled. Then add as much water as the pot will hold. Put on the fire to

boil, but do not allow to boil dry. The wool will dye a lovely yellow

colour which is a good basis for green when indigo is added. If a moss

green is require, add gall apples and iron mordant towards the end of

dying. Purple and brown tints can be obtained by using old heather tops.

If wanted for winter use, the tips of the heather plant should be

picked just before they come into flower. If it is to be used fresh, it

can be gathered as long as the flower is in bloom.

The resultant dye is a mordant dye which means the fibre requires

special preparation before it can absorb the colour. The treatment is 4oz alum and 2oz

cream of tartar to every 1 lb of wool.

A Taste of Heather

HEATHER ALE - A Galloway Legend

From the bonny bells of heather,

They brewed a drink Lang Syne

Was sweeter far than honey

Was stronger far than wine.

R.L. Stevenson

Heather has been used over the years to flavour many different foods

and drinks. Little is actually known about the early beverages of

Scotland. However, many tales are told of brewing ales and wines from

heather flowers. One such brew was known as Heather Crap Ale.

TRADITIONAL RECIPE FOR HEATHER ALE

Ingredients: Heather, hops, barm,

syrup, ginger and water. ‘Crop the heather when it is in full bloom,

enough to fill a large pot. Cover the croppings with water and set to

boil for one hour Then strain into a clean tub. Measure the liquid and

for every dozen bottles add one ounce of ground ginger, half an ounce of

hops and one pound of golden syrup. Bring to the boil again and simmer

for 20 minutes. Strain into a clean cask. Let it stand until milk-warm

and then add a teacupful of good barm. Cover with a coarse cloth and let it stand till next day Skim carefully and pour the liquid

gently into a clean tub so that the barm is left at the bottom of the

cask. Bottle and cork tightly The ale will be ready for use in 2 or 3

days and makes a very refreshing and wholesome drink as there is a good

deal of spirit in heather’

As recently as 1993, an AlIoa brewery went into production of Heather

Ale using an ancient recipe.

TRADITIONAL RECIPE FOR HEATHER WINE.

1 ½Ibs. Heather Tips (in full bloom)

1 Gallon water

3-4 lbs. Sugar (according to sweetness desired)

2 Lemons

2 Oranges

1 teasp. dried yeast

1 teasp. yeast nutrient.

Cover heather with the water and boil for one hour. Strain off liquid and measure. Restore

to one gallon, and add sugar. Stir until completely dissolved. When the

temperature drops to 70F, add yeast and nutrient. Leave for 14 days.

Then strain into fermentation jar, and when fermentation ceases, strain

and bottle. Keep for at least six months!

HEATHER TEA

Gather the flowering heather and after breaking off the hard woody

pieces, spread it in a cool open space and leave for approximately 12 -

16 hours. This should, in theory, allow a slight wither to take place -

but with heather having a hard leaf, this is not too noticeable.

Put the heather into a liquidiser and

bruise and break-up the heather as much as possible. After this spread

thinly in a cool place and leave for a minimum of 3 hours to allow a

ferment to take place. This should be apparent from a darkening of the

mash. After this, put into an oven, temperature 200-250F until the

heather is dry and crisp. The tea retains its misty mauve colour and

looks attractive. Used on its own, the product gives a thin liquor.

Mixed in equal parts with ordinary tea however, it gives a much stronger

flavoursome brew. This is a proper tea - not herbs masquerading as tea.

Tinkers Tea

Trout fishermen having a day on the loch

use the following method to make tea - they fill the kettle with loch

water and take it to the shore, a sprig of heather and tea is then

deposited in the kettle. Next, set old dry heather under and make a

mountain of heather over the kettle and ignite. By the time it has burnt

out the tea is ready and has a heathery flavour. This method was

described to me by Mr George Sproat, 4 Rockfleld Road, Tobermory, Isle

of Mull.

On the Isle of Skye they had a very

simple remedy for tea which had been ruined by smoke from the fire. The

solution - a sprig of heather simply placed in the cup!

Heather Whisky

It is said that some of the finest brands

of whisky derive some of their most delicate flavours from the heather.

At the Highland Park Distillery, in

Kirkwall, Orkney, there was a peculiarly shaped timber building,

referred to as the ‘Heather House’. This was where heather, which

had been gathered in the month of July when the plant was in full bloom,

was stored. Carefully cut off near the root, and tied into small faggots

of about a dozen branches each, the heather was used on the peat fire to

help dry the malt and impart a delicate flavour which, was claimed, to

give Highland Park Distillery its unique taste.

It is interesting to note that in former

times the wooden containers for fermentation, known in whisky

distilleries as ‘washbacks’, would be cleaned using heather besoms.

And when new stills were installed, bundles of heather would be placed

in the water and boiled in order to sweeten the still before the first

distillation took place.

In the nineteenth century and possibly

even earlier, illicit stills were used to make whisky - in broad

daylight. The crofters were able to do this because, by gathering up and

using old stumps of burnt heather, they could make a fire without smoke,

and so not raise suspicion!

Heather Honey

There is no other honey quite like

heather honey.

Quite different even physically from all

other honeys, pure heather honey is sought after by the epicure and

commands a high price. Bright golden brown with a pronounced and

characteristic flavour, the harvest of heather honey is the premier

honey crop in this country.

In some respects, gathering the honey

from heather is easier than gathering honey from any other flower

source. There is little likelihood of bees swarming when taken to the

heather, routine inspection of the hives can be dispensed with and the

expectation of a good harvest is reasonably certain - dependent on good

weather and no early frosts.

Transportation of the hives to the

heather moors is generally undertaken between the end of July and the

12th of August, although this can vary according to the season. However

it is advisable to try to catch the best of the Bell Heather and Cross

Leaved Heath Crops when they are in the first flush of bloom.

Transportation of the bees is best carried out either in the cool of the

evening or the early hours of morning. This reduces losses by

suffocation.

Due to the flowering structure of the

heather plants, where there are numerous flowers on spikes, close to one

another in vast expanses of bloom, a considerable amount of honey can be

collected in a comparatively short time. Being bell-shaped, the flower

is easily entered with the nectar readily available to the visiting bee.

The corolla tubes of these small flowers are approximately 2-3mm long

with the nectar being concealed at the flowers base. This is easily

sought out and collected by the honey bee’s spoon-tipped tongue which

is approximately 6mm long. The nectar is converted to honey by the bees

themselves.

Bell Heather honey is a thinner honey

with a port wine colour and a strong characteristic flavour, whilst

Cross Leaved Heath Honey is much thinner and lighter in colour.

Weather Predictions

Even predictions in the weather have been

associated with heather. It is said, in Scotland, that an extremely rich

blossom on the heather during August and September, is followed by

severe weather in winter. Whilst another widely held belief,

particularly throughout the south of the country and the Cheviot range,

is that the buming of the heather ‘doth draw doon the rain’!

Plant Badges of the Clans

As already mentioned, Heather can be

used, in conjunction with deerhorn, silver and pewter, to make colourful

and effective jewellery. But another important decorative use for

heather was as a plant badge of the clans. This was used long before the

tradition of heraldic badges with the appropriate chiefs crest, straps,

buckles and mottos.

Referred to as ‘Heather Taps’, these

natural plant badges were worn by the Highlanders in the seventeenth

century, if not before, and were placed behind the crest in the bonnet.

Heather (Fraoch) was the emblem of the clans MacAlister, MacDonell,

Shaw, Farquharson, Maclntyre and Mac Donald, with white heather (Fraoch

GeaI) pertaining to MacPherson.

It is said that the chiefs of the clan

Donald carried into battle, as an emblem of their race, a bunch of wild

heather hung from the point of a quivering spear.

Another way in which heather was used

decoratively was in the form of dirk handles. Made from the stems and

roots of the plant and carved deeply in Celtic designs these were worn

on kilts around the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The Healing Properties of Heather

The healing properties of heather have

been recorded as far back as the middle ages, with books on other herbs

and their uses dating even further back to the seventh century. The healing properties of heather have

been recorded as far back as the middle ages, with books on other herbs

and their uses dating even further back to the seventh century.

A German book, written in 1565, describes

the famous doctor Paulus Aegineta as using the flowers, leaves and stems

to heal all types of sores incuding ulcers - both internally and

externally.

Fuchs wrote in 1543 that the healing

effect of the plant could ease insect bites. Whilst Matthioulos, who

lived round about the same time, used the plant in drug form to heal

snake bites, eye infections, infections of the spleen and in preventing

the formation of stones in internal organs.

Nicolas Alexandre, a Benedictine monk,

wrote that boiling heather stems and drinking the liquid for thirty

consecutive days, morning and evening, was sufficient to dissolve kidney

stones. He added, that the patient should also bathe in the Heather

water.

Heather has even been found to help

nursing mothers produce more milk. Schelenz wrote in 1914 that Heather

was a household remedy for all sorts of illnesses and complaints.

However by the turn of the century, heather, in medical terms was

generally associated with the prevention and treatment of stones in the

bladder and kidney area.

Since 1930, Heather, referred to by the

medical profession as Herba Callunae, has been acknowledged by many

doctors and chemists as effective against arthritis, spleen complaints,

formation of stones, stomach and back ache, even paralysis and

tuberculosis. This remarkable plant, which is quite safe for use by

diabetics, is also known to be good for sore throats, gout, catarrh and

coughs. Some say it even cleanses the blood getting rid of exzema and

fevers.

Medical herbalists, to this day, use

Calluna vulgaris in the treatment of certain disorders. Containing

tannin and several other components, it is used particularly in the

treatment of cystitis (bladder infection), as its action is diuretic and

antimicrobial.

In the mountain regions of Europe the

plant is still used to make a linement for arthritis and rheumatism by

softening the herb in alcohol.

Honey for Hay Fever

Pure Heather Honey is recommended for hay

fever sufferers.

Heather was not only associated with

curing illnesses - it was, according to the Scots National Dictionary,

also used figuratively, to describe ailments and other peculiarities

common to country folk. HEATHER ILL This was the description used

to describe constipation of the bowels. HEATHER LAMP A springy

step common among people accustomed to walking over heathery ground. The

term ‘heather lamping’, refers to lifting feet high when walking -

sometimes called a ‘heather step’. Walking with a step high and wide

was described as walking with ‘heather legs’. HEATHER HEADED Sometimes

referred to as ‘heather heidit’, this is the description given to

someone with a rather dishevelled head of hair - and indicates a rustic

or country background. HEATHER GOOSE This was the term used to descibe a

dolt or ninny. HEATHER PIKER This

term was a contemptuous epithet for a person living in a poverty

stricken or miserly way. HEATHER WIGHT The

name given to a Highlander. HEATHER LOWPER A hill dweller,

countryman — known as a Heather-Stopper in Perth. HETHER MAN, HATHER

A heather seller. Also found purporting to be a term in free

masonry.

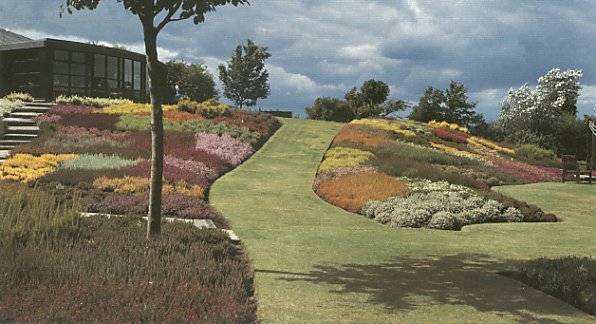

A Heather Garden

As a plant with so many advantages for

the present day gardener, it will come as no surprise to find that

Heathers are more popular than ever! Providing colour all year round

with foliage and flower, heathers are evergreen and will thrive for many

years. Inexpensive to purchase and relatively easy to grow, heathers,

once established, will provide a weed free garden which requires the

minimum of maintenance.

Easy to propagate, heathers are also

relatively free from diseases and pests. Small wonder then, that

landscape projects large and small, from industrial sites and motorways

to housing developments and car parks, make great use of this plant.

Until recently little scientific work has

actually been carried out on the hybridisation of heathers, but yet,

hundreds of different cultivars are now available from specialist

nurseries. Many of these cultivars have been found in the wild as ‘chance’

seedlings, perpetuated by vegetative propagation. Other cultivars arrive

as ‘chance’ seedlings in nurseries - as sports or mutations in

gardens. Each with their own distinctive qualities.

For instance, plants brought back from

the remote island group of St. Kilda, (approximately 50 miles west of

the Outer Hebrides and 100 miles from the mainland), are extremely dwarf

and spreading. They remain so even in cultivation, their characteristics

having been developed to cope with the extreme exposure experienced on

the islands.

Cultivars discovered quite by chance

include one which was found growing as a sprig on Calluna ‘County

Wicklow’. ‘County Wicklow’ has double pink flowers, but this

cultivar had double white flowers. The sprig, found in a garden in

Argyll, has since been propagated successfully and is now catalogued

under the name Kinlochruel. (A selection of cultivars are listed towards

the end of this section.)

The heather gardener has many cultivars

to choose from and one glance at the photographs in this page should

help to convince even the most reluctant gardener that, together with a

few conifers and shrubs, an attractive and easily maintained garden can

be easily achieved.

The Heather Society

Founded in 1963, to assist in the

advancement of horticulture, and in particular, the improvement of, and

research into the growing of heaths, heathers and associated plants.

It publishes a Year Book and three

Bulletins annually to keep members up to date. It maintains a slide

library, provides free technical advice and arranges local and an annual

national conference.

For details of membership contact: Mrs

A. Small, Administrator, Denbeigh,

All Saints Road, Creeting St. Mary,

IPSWICH, SUFFOLK 1P6 8PJ.

Affiliated Societies

North American Heather Society.

Secretary: Walter H. Wornick, Highland

View, P0. Box 101, Aistead, New

Hampshire 03602, U.S.A.

Nederlandse Heldevereniging ‘Erlcultura’.

Secretary: Mr. J. Dahm, Esdoornstraat

54, 6681 ZM Bemmel, Netherlands.

Gesellschatt der Heldefreunde.

Chairman: Fritz Kircher, Tangstedter Landstrasse 276, 2000 Hamburg 62,

Germany.

SPEYSIDE HEATHER CENTRE

Was

originated in 1972 - by David and Betty Lambie with the intention of

being Scotland’s Heather Specialists. Located appropriately in the

heart of Speyside in the central Highlands of Scotland amidst glorious

scenery the award winning centre now attracts aprox 85,000 visitors

annually.

Any enquiries the reader may have should

be addressed to:

Speyside

Heather Garden & Visitor Centre

Skye of Curr

Dulnain Bridge

Inverness-shire,

Scotland PH26 3PA.

Tel: 01479 851359

International: +44 1479 851359

Fax: 01479 851396

Email: enquiries@heathercentre.com

The Lambies

Our thanks to the author of this

book, David Lambie, for letting us take part of his book to publish

here. The whole book is available for purchase at their web site and

includes details of the many heathers available and how to grow them as

well as suggested heather garden layouts. When you visit their centre

make sure to visit their Clootie Dumpling restaurant!

Speyside

Heather Garden & Visitor Centre

The Heather in Lore, Lyric and Lay

By Alexander Wallace (1903)

RUSKIN, in one of his friendly lecture-talks on art, with the

sympathetic spiritual perception and originality of thought

which characterize his unique genius, says: "Now, what we

especially need for educational purposes, is to know, not the

anatomy of plants, but their biography—how and where they live

and die, their tempers, benevolences. distresses and virtues."

The quaint sentiment voiced by the great philosopher many years

ago is somewhat significantly in harmony with this dawning time

of a simpler and brighter understanding of humanity and of

nature. And could we find for such a flower biography a subject

more entrancing, so seductive, almost eerie, so plaintively

sturdy, so instilled with romance, with patriotism and with

pathos—as the Highland Heather?

There dwells, perhaps, no

solitary plant or flower in the sheltered garden or in the

lonely wild, whose family ties show no modest record hidden

somewhere in the stately annals of history; but the crude fact

of history, like a tale that is listlessly told, has little

power to charm where lack the flash and glow of emotional ardor;

and so I have invoked to my humble biographical narrative of

this bonnie floral hermit on our bleak majestic Highlands, that

ancient patron Muse of Scotia's departed minstrels—the Spirit of

Caledonia. We learn from the histories of the vegetable

kingdom that Calitma vulgaris—the generally accepted botanical

term for Heather—has a wide distribution throughout European

countries, and in other parts of the world. But so closely has

the word Heather become associated with Scotland, that whenever

we hear it spoken, or see it written, the fancy instinctively

roams to the "land of brown heath and shaggy wood," the beauty

of whose stem mountains, softened with their autumnal vesture of

purple and brown blending in every-varying and never exhausted

tints, has baffled the painter's genius, enchanted the poets

vision, and inspired monarch and peasant alike to sing its

praises. The Heather enters into the literature, the poetry,

the lyrics, and into the home life of the Scottish people, to a

degree unsurpassed by any other plant in the history of nations

and the wonder is that its own interesting story has not before

been told in some complete form. Scotland and the heather are

inseparable; the flower derives its inheritance of unique

renown, and somewhat, too, of rugged temperament, from the

Caledonian mountain wild which has become so characteristically

its home; thus it is in its identity with the land of Bums that

I wish principally to consider it.

For the purpose of a

clearer elucidation of the history and utility of the plant

itself, however, it has been thought necessary to go beyond

Scotland's borders; still it is believed that this further subject

matter presented will be welcomed with interest in localities

wherever Scotsmen gather—and by those for whom all things

Scottish have a fascination.

A more opportune time, perhaps,

could not have been chosen in which to tell the absorbing

nature-story of the Heather than this year, the centenary of the

council at which Science, in its discernment, removed from the

plant its ancient and ill-deserved appellation of Erica, and

clothed it with its present designation of Calluna, so much more

truly expressive of its unique beauty and charm.

"Co attempt

has been made to enter fully into the botanical or cultural

details connected with the plant. These have been treated only

in a casual manner: still, it is hoped sufficient information

has been given to prove serviceable. The effort has been rather

to cull from the multitude of references to the Heather

abounding in Scottish and other literature, and to weave the

sprays thus gathered into a literary garland the beauty and

attractiveness of which shall lie in the depth of the sentiment

pervading it, and in the aroma of patriotic love that it

exhales. Defects in the treatment of the subject may assert

themselves to the critical reader. No one will be more conscious

of these imperfections than is the author; but, in the language

of an old writer, for faults of omission and commission, "I

referre me wholy to the learned correction of the wise; for t'el

I wote, that no treatise can alwayes be so workmanly handled but

that somewhat sometyntes may fall out amisse. contrarie to the

mmdc of the vryter, and comrade to

the expectation of the reader; wherefore my petition to thee,

Gentle Reader, is to accept those my travyles wyth that mimic I

doe offer them to thee, and to take gently that I give gladly;

in so doing I shall thinice my paynes well bestowed, and shall

bee encouraged hereafter to trust more unto thy courtesie."

To the friends who have so willingly and

generously assisted me in the collection of the information

submitted, I tender my sincere thanks. Particularly, in this

respect, am I under obligation to Mr. Robert Cameron, Curator of

the Botanic Gardens, Harvard University: Mr. Jackson Dawson, of

the Arnold Arboretum; Mr. William Falconer, Superintendent of

Allegheny (FL) Cemetery; Mr. George W. Oliver, of the Bureau of

Plant Industry, Department of Agriculture, Washington, D. C; and

Mr. Joseph Meehan, of Germantown, Pa.

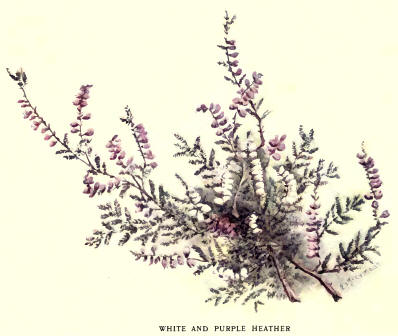

Especially am I indebted to Miss Elizabeth

I. Bierstadt, daughter of Mr. Edward Bierstadt, of New York

City, and niece of the celebrated American landscape painter of

that name, for the charming life-like painting of the sprays of

Heather, reproduced from flowers received from Scotland, which

form the frontis. piece to this work.

I also tender my acknowledgments to Mr. H.

C. Dugan, of Aberdeen, Scotland, for photographs of Scottish

mountain scenery.

I send forth

this little volume, the result of some years of painstaking

research during the spare moments snatched from a rather busy

life, as the tribute Of an expatriated Scotsman to the mountain

flower of his home land, hoping that a perusal of its pages may

but deepen the ardor of Scotland's sans and daughters everywhere

to continue to sing, with the best heart and voice at their

command, the praises of their native Heather.

ALEXAND€R WALLACE

New York, December, 12.

Contents

Etymology

Botanical History

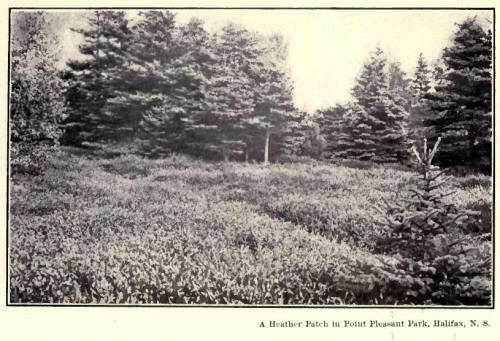

Distribution of the Heather

The

Heather Abroad

In America

Cultivation in America

In the British Colonies

In

Australia

In New Zealand

In South Africa

In India

Varieties of the Heather

Symbiosis of the Heather

Economics of the Heather

Heather Thatch

Heather Beds

Besoms and Scrubbing Brushes

Uses in Dyeing

Medicinal Virtue

As a Forage

Plant

Bees and Heather

Miscellaneous Use

Peat Making

Heather Ale

Heather Burning

Heather Bells

in Scottish Scenery

The Magic of the Heather

Heather, the

Martyr's Friend

The Heather as a Clan Badge

Heather Lore

White Heather

Shadow Folk of Heather Haunts

Heather Jock

The Comrade of the Heather

Grouse: The Heather Bird

Chimings of the Heather Bells

Love Among the Heather

At Rest, where Heather Blooms

Heather Lays

A Bit of

Heather

The Bed of Heath

Heather Ale, a

Galloway Legend

Heather Burning

Moorburn

The Wee Sprig o' Heather

Heather Musings

Scotch Heather

My Wee Bit Heather

On a Spray

of Heather

Heather Jock

The Rose Among the

Heather

A Sprig of Heather

The Flowers of

Scotland

A Sprig of White Heather

The

Heather

The Faded Heather

Heath

The Heather at My Door

To a Wild Heath Flower

Scotch Heather

The Heather

Clover and

Heather

The Heather

Songs of the Heather

Among the Heather

The Plaid Among the Heather

The Heather Belt

The Hills of the Heather

The Hielan' Heather

The Hieland Heather

My

Heather Hills

The Land of the Bright Blooming Heather

Sweet Heather Bell

O'er the Muir Amang the Heather

Amang the Braes o' Blooming Heather

When the Heather

Scents the Air

My Heather Land

Poetry and Songs

Quoted from:

Bonnie Auld Scotland

Our Ain

Land

The Land o' Cakes

The Freedom of the

Hills

Know'st Thou the Land?

Hurrah for the

Highlands

The Covenanter's Tomb

Cailleach

Bein-y-Vreich

The Cameron Men

Is Your

War-pipe Asleep?..

The Yellow Locks o' Charlie

Wha'll be King but Charlie?

When Charlie to the

Highlands Came

Shagram's Farewell to Shetland

The Scotsman's Farewell

Farewell to the Land

I'll Loe Thee, Annie

The. Hills of the Highlands

The Chieftain to His Bride

Ca' the Yowes

O'er the Mountain

The Crook and the Plaid

I'll Twine a Wreath

The Heathy Hills

Lass of

Logie

My Highland Cot

Scotland Dear

Scotland's Hills

The Hills O' Gallowa'

Hame

Flowers of the Moorland

On the Hills

Solitude

Send a bit

of heather o'er the sea

To Scotia's sons, where'er they be;

Its bloom will bring to mind

Scenes and faces left

behind,

And anew each heart will bind

To the old countrie.

Send a bit of heather o'er the sea;

Transported back each

heart will be

To fair Scotland's wooded hills,

Hear the

music of her rills,

And the mavis as it trills

In the old

countrie.

Send a bit of heather o'er the sea;

Simple offering though it be,

Prized 'twill be where

fairest flowers

Blossom in their tropic bowers,

Or where

iceberg frowning towers

O'er the sea.

Send

a bit of heather o'er the sea;

A dear remembrance may it be

To the ones now vigil keeping

O'er our soldiers quietly

sleeping;

Send the heather—Scotland's greeting—

O'er the

sea.

—M. CARTER, in Scottish American

|