|

CUSHION PLANTS

In Scotland we have four plants which belong to this

interesting group. Two of them, the Moss Campion (Silene acaulis)

and the Mossy Cherleria (Alsine sedoides), will be described now.

The other two plants are Saxifrages and will be described in the following

chapter.

Moss Campion

(Silene acaulis) Moss Campion

(Silene acaulis)

One can find the starry tufts of this plant at 4,000 feet on the wild

Cairngorm plateaux, surrounded by deep snow fields, their bright green

leaves and pink, star-like flowers brightening the black rocks and

contrasting strangely with the glistening expanse around them. Its range

in the Highlands is that of the highest mountains and it is widely spread

throughout the whole area. One must ascend to more than 2,500 feet to

find it, but above that height one can almost be sure of doing so.

The Moss Campion is a typical cushion plant and a

detailed study of it is a grand insight into the architecture of alpine

plants.

It has a very short, woody, perennial stock buried as

far as possible in the poor soil in which it grows. Below ground is a

root system which is of huge size in proportion to the cushion above

ground. These roots bore down where the fierce frosts of winter cannot

reach and where they can always find moisture, even in the worst of summer

droughts.

Throughout the short summer, the woody rhizome stores

up food and energy, so that, after the long winter sleep, the plant can

commence the life cycle as quickly as possible. The whole process, from

the bursting leaf buds to the dispersal of the seeds, must take place

before the snow and cold return in the early autumn. This, in a region

where the entire season may be four months or less, is of vital importance

to success in the life struggle.

Above ground the stock forms many branches which again

branch to form a close, compact, hemispherical cushion. The branches are

clothed below with the brown, dead leaves of other years, but above they

are closely covered with bright green leaves. These are very small and

more like the leaves of a moss than of a plant of a higher order.

Owing to the closeness of the branches and the dense

covering of leaves, the cushions have a very compact appearance and are

well able to bear the weight of snow without being crushed or broken.

Also the fierce winds which sweep their exposed habitat are unable to

uproot the plant or break its branches.

The leaves, themselves, are very small in comparison

with the size of the plant. They are packed very closely together and

this arrangement helps to cut down undue transpiration, a very important

consideration in their often desert-like surroundings. They also point

more or less upwards and so expose a very small surface to the fierce sun

which beats down upon them in the summer.

From the axils of these leaves arise slender pedicels

which are surmounted by a single large rose-purple flower. The number of

flowers on a single cushion is enormous, and no one who has not seen this

beautiful flower in its natural surroundings, can ever imagine how

beautiful these starry cushions really are.

The large size of the flowers and their crowding

together helps to make them very conspicuous to the small butterflies

which chiefly pollinate them. For this reason they are of a reddish

hue--red being the favourite colour of butterflies.

Each flower has a bell-shaped, smooth calyx from which

spring the five reddish-purple petals. These petals have a very narrow

claw which is protected by the clayx, and a broad heart-shaped limb which

is placed at right-angles to the calyx tube. The flower itself thus

appears as a flat disc; this makes an ideal landing ground for winged

visitors.

At the base of each limb is a tiny fringed scale which

prevents crawling insects gaining access to the corolla tube and the

nectarines at its base. Thus only long-tongued insects, such as

butterflies, can reach the nectar. Thus this exquisite flower guards

against pilferers and when the butterflies arrive they know that they will

find an unspoiled store of nectar waiting for them.

The arrangement of the flowers in this species, as in

many of the Pink Family, is rather peculiar. All the flowers on any

particular cushion are of the same sex, but there are three different

types of clumps. There are those in which the flowers have both stamens

and pistils; these clumps are rare. Others have male flowers only and

others only female flowers. The first of these groups have flowers with

ten stamens and a pistil with three curved styles. The stamens mature

before the pistil which remains with its three styles pressed together.

On the afternoon that the flower first expands, five stamens lengthen and

stand erect. By the following morning the have shed their pollen and the

anthers have withered. That afternoon the next five stamens follow the

same process, so that by the following day all the pollen has been shed.

That afternoon the styles lengthen, open out and curve backwards. They

remain receptive for another day.

>From this arrangement it will be seen that it is

nearly impossible for a flower to be self-fertilized. A butterfly must

arrive with pollen from a newly-opened flower to pollinate older flowers

with receptive stigmas.

If no insects visit the flower, it is possible for the

stigmas to recurve so far that they may be pollinated by pollen deposited

on the petals by their own stamens. In the other two types of cushions,

of course, self-fertilization is absolutely impossible. So imperative is

the plantís desire to escape from self-fertilization that it has gone to

the length of forming plants which can never seed in order that the

seed-bearing flowers may produce the greatest quantity and the best

quality of seed. In the event of a very bad summer, insect visitors may

be so rare that hardly any seed is set by the dioeciously plants which are

absolutely dependent of their winged messengers. Here, however, the fact

remains that the rarer flowers containing both male and female flowers

will always set some seed, even if not visited by insects, so that the

continuation of the species seed, even if not visited by insects, so that

the continuation of the species will always be ensured.

After fertilization, the flowers wither and a brown

capsule is left, which contains many very small light sees. When the

capsules are ripe, valves open at the top and the strong wind jerk out the

seeds, which being very light may travel a considerable distance. Many

probably fall on bare rocks and, of course, die; but a few fall on

favorable soil where in due course, they will also form the same beautiful

cushions.

It will thus be seen how amazingly this plant has

modeled itself to the environment. It has set out to live under

conditions which most plants could not have tolerated and it has made an

amazing success of it. So much so, that it is to be found in abundance in

every flora of the northern hemisphere and also in the arctic regions.

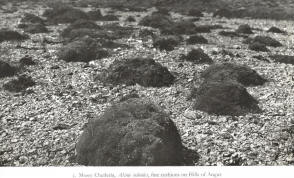

Mossy Cherleria

(Alsine sedoides) Mossy Cherleria

(Alsine sedoides)

Another good example of a cushion plant is the Mossy Cherleria, which also

belongs to the Pink Family. It is fairly common upon the highest mountain

tops and is to be found on rocky ridges, scree slopes and among grass.

It forms large compact, hemispherical, bright green

cushions which may be as much as one foot across. The plant produces an

enormous number of small branches which are clothed with many, small awl

shaped leaves in opposite pairs. They have short hairs along the margin

and veins.

The large cushions are perfectly constructed to support

the weight of winter snow and to resist the fierce attacks of the wind.

Massed together as they are in a close cushion, the transpiration rate of

the leave is much reduced. The plant is securely anchored in the rocky

soil by tough, thick taproot, which acts as a storage organ during winter.

In striking contrast to the Moss Campion, the flowers

are quite inconspicuous. Each flower is produced on a slender stalk from

the summit of a tuft of leaves. The flowers usually possess no petals,

the conspicuous portion being five green sepals with membranous margins.

Each flower possesses ten stamens and three stigmas produced on shortish

styles. The flowers also possess five glands between the stamens and these

produce nectar.

The flowers are visited by small flies, but they are

usually self-fertilized as the stamens and stigmas are at the same level.

This plant is not dependent on insect for the continuation of species and,

in spite of continued self-fertilization, is an abundant and thriving

species. I shall have some more to say with regard to the advantages of

cross- and self- fertilization in a later chapter.

The seeds are small and light and contained in a tiny

capsule opening at the summit by three valves. The wind causes the seeds

to be thrown out of the capsules and they may, then, be carried a

considerable distance.

We shall meet with two more fine examples of cushion

plants in the next chapter. Suffice it to say that this plant

architecture is a very common among the high alpine plants to be found on

the Swiss Alps. |