PREFACE

When the late Dr

Taylor conceived the idea of preparing a volume on Craigcrook,

his chief object was to secure the reminiscences of Lord

Moncreiff, whose knowledge of Jeffrey and his cotemporaries

rendered him peculiarly fitted to reproduce the genius of the

place as well as of its most famous occupant. No other living

writer could possibly have given to the public such store of

pleasant memories as is contained in the chapter which forms the

main portion of this book. The great critic lives again in these

pages; and though we are often carried away from the "tea roses”

and “grey towers” to mingle with the men of note and power who

were his friends, Jeffrey is always the centre, and Craigcrook

the happy “muster ground ” of them all.

Apart from this

special association, which is the dominant note of the book, the

story of Craigcrook is well worthy of permanent record. It takes

us back almost to the days of Robert the Bruce. A portion of the

present building probably dates from before the battle of

Pinkie. It was fortified by the “King’s party” in the troublous

times of Queen Mary. Passing through several hands, it was

finally bequeathed in 1719, and the whole property is now

administered by trustees for charitable purposes.

During this

century the Castle has had a variety of tenants, but the glamour

of the place has never failed to exercise its power over them.

Brightness and

hospitality are now, as ever, identified with Craigcrook. Nature

has invested it with the charm of quiet beauty, which seems to

grow with the passing years. The changes which have been

gradually made in the building are in perfect harmony with the

original, and also with its surroundings. These have so far been

carefully detailed by Mr Ross in his valuable note. It remains

only to be said that the present occupant, Mr Robert Croall,

with warm appreciation of the beauty and traditions of

Craigcrook, has recently (1891) enlarged the building in a

manner which enhances its dignity, without in the least degree

detracting from its sweetness and grace. This extension, as

shown at pages 12 and 18, was carried out with characteristic

skill by Mr Thomas Leadbetter. The delay in issuing this volume

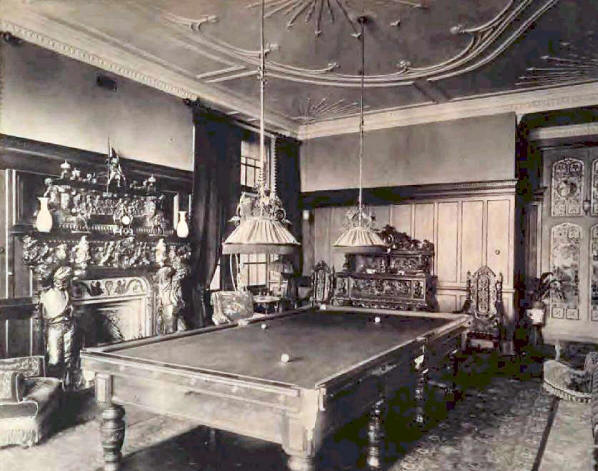

is the less to be regretted, as otherwise the photographs by

Messrs Bedford, Lemere & Co., of London, which add so greatly to

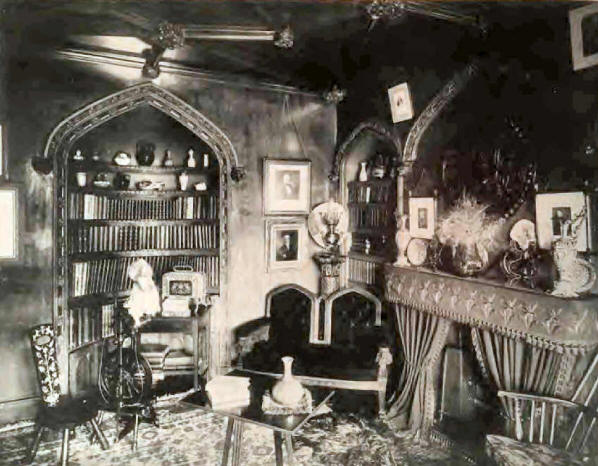

its value, would have been incomplete. Of special interest is

the view at page 42, showing the interior of Jeffrey’s study,

and a glimpse of the chair on which the “thunderer” was wont to

sit.

A pathetic

interest is added to the book by the fact that the learned

Editor has not been spared to see the publication of what was to

him a labour of love. With the author of “The Great Historic

Families of Scotland ” there has gone from us a rich treasure of

byegone lore. His love for the past was a passion, and bore many

valuable fruits. Not the least interesting of these is the

present sketch of an ancient Castle, whose history and

associations had always for him a special charm.

A. WALLACE

WILLIAMSON

Edinburgh, May 1892.

CRAIGCROOK,

HE lands of

Craigcrook belonged in the fourteenth century, and probably at a

much earlier period, to the famous family of Graham, ancestors

of the ducal house of Montrose, who early in the preceding

century held extensive possessions in the adjoining district of

Midlothian. It is mentioned in Wood’s History of Cramond,

published in 1794, that in Father Hay’s Collection of Charters

there is preserved a copy of a Resignation made by Patrick de

Graham, Lord of Kinpunt, and David de Graham, Lord of Dundaff,

of all right or claim they could have to the lands of Craigcrook,

in favour of John de Allyncrum, burgess of Edinburgh, bearing

date 9th April 1362. That worthy citizen in turn settled them on

a chaplain officiating at “Our Lady’s altar in the church of St.

Giles, and his successors, for ever, to be nominated by the

magistrates of Edinburgh.” The pious donor sets forth that this

foundation was to be for the salvation of the souls of the

illustrious Robert Bruce, late King of Scotland, of his wife

Queen Elizabeth, and for the safety and prosperity of their son,

the present King David; of William Earl of Douglas, his wife

lady Margaret, and of Archibald Douglas, during their lifetime,

and for the salvation of their souls after death, and of the

souls of the burgesses and commonalty of the city of Edinburgh,

and of their ancestors and successors; for the souls of his own

father and mother, brothers, sisters, and friends, then of

himself and of his spouse, Joanne, and finally of all faithful

souls deceased.

In 1376 the lands

of Craigcrook were let in feu-farm to Patrick and John Leper, on

condition of their paying an annual rent of £6, 6s. 8d. Scots,

for the support of the altar of the Virgin Mary, and of the

chaplain officiating there. In November 1428 John Leper resigned

these lands to John de Hill and his successors, chaplains at

that altar. Sir Simon Pivston of Graigmillar, Provost of

Edinburgh, made them over in 1540 to Sir Edward Marjoribanks,

Prebend of Craigcrook, and he in the following year let the

lands to George Kirkaldy, brother of Sir James Kirkaldy of

Grange, Lord High Treasurer of Scotland, on payment of £27, 6s.

8d. Scots. But in 1542 he restored Craigcrook to Sir Edward, and

the lands were assigned by him, with the consent of the Provost

and Chapter of the Collegiate Church of St. Giles, in perpetual

feu-farm, to William Adamson, burgess of Edinburgh—an example of

the manner in which, on the approaching downfall of the Romish

Church, ecclesiastical property was alienated to secular

purposes. It is probable that the new proprietor of Craigcrook

was the son of a William Adamson, who was one of the magistrates

of Edinburgh, and one of the guardians of the city after the

battle of Flodden. It appears that the second William Adamson,

who was killed at the battle of Pinkie in 1547, had inherited or

acquired considerable property, including Clenniston, Craigleith,

and part of Cramond, in the vicinity of Craigecrook, and it is

probable that the present castle was erected by him. or by his

grandson, who was his immediate successor. The only mention of

Craigcrook in connection with public events was during the

minority of James VI., and his mother Queen Mary’s imprisonment

in England, while the Castle of Edinburgh was held in her

interest by Kirkaldy of Grange. The King’s party, in order to

prevent the “inbringing of victuals” to the garrison, fortified

Merchiston, Gray-cruik (as the fortalice is termed by Keith and

Spottiswood), Lauriston, and “other places of strength about the

town of Edinburgh and “all inhabitainis within two myles to

Edinburgh wer constraint to leave thair houssis and landis to

that effect Edinburgh sould have na furneissing.” Craigcrook

remained for several generations in the possession of the

Adamsons, until in 1659 Robert Adamson disposed of his extensive

estates in the parish of Cramond, and sold Craigcrook to John

Mein, merchant in Edinburgh. Ten years later it was purchased

from Mein’s son by John Hall, one of the bailies, and afterwards

Lord Provost of Edinburgh, created a Baronet in 1687, and the

founder of the family of the Halls of Dunglass.. On his

acquisition of the Dunglaas estate—an old possession of the

great family of Home—he sold Craigcrook to Walter Pringle,

Advocate, from whose son it was purchased by John Strachan,

Clerk to the Signet.

At his death in

1719 Strachan bequeathed the whole of his property, real and

personal—including the estates of Craigcrook, North Clermiston,

and Boddams (with the exception of some small sums to his

brother and two nieces)—“mortified for charitable and pious

uses.” Mr. Strachan’s trustees, consisting of two Advocates, two

Writers to the Signet, and the Presbytery of Edinburgh, resolved

that the benefits of the Craigcrook Mortification should be

conferred on “poor old men, women, and orphans.” They also

determined that no old person should be admitted as a pensioner

under the age of sixty-four, nor any orphan above the age of

twelve. Fifty merks Scots were allotted to the poor of the

Advocates, one hundred merks to those of the Writers to the

Signet. Twenty pounds annually are granted for a Bible to one of

the members of the Presbytery, beginning with the Moderator, and

going through the others in rotation.

About the

beginning of the present century Craigcrook was the residence

for several years of Mr. Archibald Constable, the distinguished

publisher. “It welcomed many a guest distinguished in the

literature of this country,” says Mr. Thomas Constable, “and

there were few eminent foreign visitors to Edinburgh who did not

bring an introduction to its most successful publisher.”

In the spring of

1815 Francis Jeffrey, who had for some years spent his summer

and autumn at Hatton, “transferred his rural deities,” says his

biographer, to Craigcrook. When he first became the tenant the

house was only an old keep, respectable for age, but

inconvenient for a family; and the ground was merely a bad

kitchen garden of about an acre; all in paltry disorder. He

immediately set about reforming. Some ill-placed walls were

removed; while others, left for shelter, were in due time loaded

with gorgeous ivy, and both protected and adorned the garden. A

useful, though humble, addition was made to the house. And by

the help of neatness, sense, evergreens, and flowers, it was

soon converted into a sweet and comfortable retreat. The house

received a more important addition many years afterwards; but it

was sufficient without this for all that his family and his

hospitalities at first required. But by degrees that earth

hunger, which Scotsmen ascribe to the possession of any portion

of the soil, came upon him, and he enlarged and improved all his

appurtenances. Two sides of the mansion were flanked by handsome

bits of evergreened lawn. Two or three western fields had their

stone fences removed, and were thrown into one, which sloped

upwards from the house to the hill, and was crowned by a

beautiful bank of wood; and the whole place, which now extended

to thirty or forty acres, was always in excellent keeping. Its

two defects were—that it had no stream, and that the hill robbed

the house of much of the sunset. Notwithstanding this, it was a

most delightful spot—the best for his purposes that he could

have found. The low ground, consisting of the house and its

precincts, contained all that could be desired for secluded

quiet, and for reasonable luxury. The hill commanded magnificent

and beautiful views, embracing some of the distant mountains in

the shires of Perth and Stirling, the near inland sea of the

Firth of Forth, Edinburgh and its associated heights, and the

green and peaceful nest of Craigcrook itself. Lockhart says:

“The windows open upon the side of a charming hill, which in all

its extent, as far as the eye can reach, is wooded most

luxuriously to the very summit. There cannot be,” he adds, “a

more delicious rest for the eyes than such an Arcadian height in

this bright and budding time of the year.” And Carlyle in his

Reminiscences says: “I remember pleasant strolls out to

Craigcrook (one of the prettiest places in the world), where, on

a Sunday especially, I might hope, what was itself a rarity with

me, to find a really companionable human acquaintance, not to

say one of such quality as this. He (Jeffrey) would wander about

the woods with me, looking on the Forth and Fife hills, on the

Pentlands, and Edinburgh Castle and city: nowhere was there such

a view.”

In a letter to

Mr. Charles Wilkes, his father-in-law, of date 7th May 1815,

Jeffrey gives the most complete description we have met with of

the state of Craigcrook when he took up his residence there. He

says:—

“We are trying to

live at this place for a few days, just to find out what scenes

are pleasant, and what holes the wind blows through. I must go

back to town in two or three days for two months, but in July we

hope to return, and finish our observations in the course of the

autumn. It will be all scramble and experiment this season, for

my new buildings will not be habitable till next year, and the

rubbish which they occasion will be increased by endless pulling

down of walls, levelling and planting of shrubs, etc. Charley

wishes me to send you a description of the place, but it will be

much shorter and more satisfactory to send you a drawing of it,

which I shall get some of my artist friends to make out. In the

meantime, try to conceive an old narrow high house, eighteen

feet wide and fifty long, with irregular projections of all

sorts; three little staircases, turrets, and a large round tower

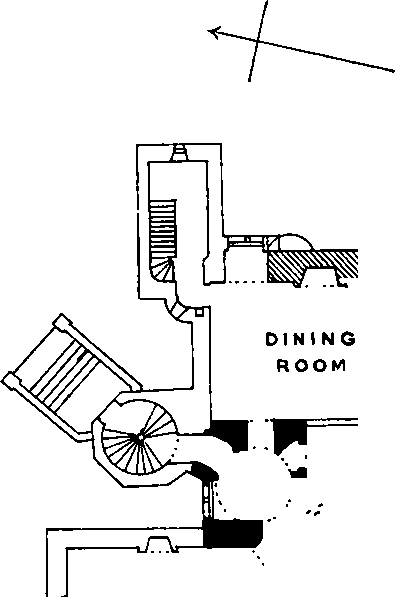

at one end; On the whole, exhibiting a ground plan like this—

with multitudes

of windows of all shapes and sizes, placed at the bottom of a

green slop, ending in a steep woody hill which rises to the

height of 300 or 400 feet on the west, and shaded with some

respectable trees near the door,—with an old garden, or rather

two, one within the other, stuck close on one side of the house,

and surrounded with massive and aged stone walls fifteen feet

high. The inner garden I mean to lay down chiefly in smooth

grass, with clustered shrubs and ornamental trees. beyond. to

mask the wall, and I am busy in widening the approaches, and

sunk fences for the high stone walls on the lawn. My chief

operation, consists in an additional building, which I have

marked but with double walls in the egant plan above, in which I

shall have one excellent and very large: room of more than

twenty-eight feet in length by eighteen in breadth, and

storeroom below, and two pretty bedchambers above. The windows

are the only ones in the whole house which will look to offer a

sequestered and solemn view, which is the chief charm of the

room.

OLD GATEWAY

DATE, A.D. 1626

It was the

favourite resort of his friends, who knew no such enjoyment as

at that place. And with the exception of Abbotsford, there were

more interesting strangers there than in any house in Scotland.

Saturday, during the summer session of the Courts, was always a

day of festivity; chiefly, but by no means exclusively, for his

friends at the Bar, many of whom were under general invitations.

Unlike some barbarous tribunals which feel no difference between

the last and any other day of the week, but more“ on with the

same stupidity through them all, and would include Sunday if

they could, our legal practitioners, like most of the other sons

of bondage in Scotland, are liberated earlier on Saturday; and

the Craigcrook party began to assemble about three, each taking

to his own enjoyment. The bowling-green was sure to have its

matches, in which the host joined with skill and keenness; the

garden had its loiterers; the flowers, not forgetting the wall

of glorious yellow roses, their worshippers; the hill its

prospect seekers. The banquet that followed was generous, the

wines never spared, but rather too various; mirth unrestrained,

except by propriety; the talk always good, but never ambitious;

and mere listeners in no disrepute. What can efface these days,

or indeed any Craigcrook day, from the recollection of those who

had the happiness of enjoying them!”

In another letter

to Mr. Wilkes, dated 9th May 1818, Jeffrey writes:—

“I have been

enlarging my domain a little, chiefly by getting in a good slice

of the wood on the hill which was formerly my boundary; my field

went square up to it before in this way. Now I have thrown my

fence back 100 yards into the wood so as to hide it entirely and

to bring the wood down into the field; and to do this

gracefully, I am cutting deep scoops and bays into it with the

fence buried in the wood. It is a great mass of wood, you will

remember, clothing all the upper part of a hill more than a mile

long, and 300 feet high; not very old nor fine wood—about forty

years old, but well mixed, of all kinds, and quite thick and

spiry.”

In the same

letter he says:—

“There is

something delicious to me in the sound even of a biting east

wind among my woods; and the sight of a clear spring bubbling

from a rock, and the smell of the budding pines and the common

field daisies, and the cawing of my rooks, and the cooing of my

cushats, are almost enough for me,—so, at least, I think to-day,

which is a kind of parting day for them, and endears them all

more than ever. Do not imagine, however, that we have nothing

better, for we have now hyacinths, auriculas, and anemones, in

great glory, besides sweetbriar, and wallflowers in abundance,

and blue gentians and violets, and plenty of rose leaves, though

no flowers yet, and apple-blossoms and sloes all around.”

“10th May.—The

larches are lovely, and the sycamores in full flush of rich,

fresh foliage; the air as soft as new milk, and the sky so

flecked with little pearly clouds full of larks, that it is

quite a misery to be obliged to wrangle in courts and sit up

half the night over dull papers. We shall come out here,

however, every Saturday.”

This appears to

be the first reference to the Saturday gatherings for the

Sessional Saturnalia, as he termed them, for which Craigcrook

was for more than thirty years so famous.

Whether alone or

with his choicest friends around him, his enjoyment of

Craigcrook and its garden and grounds was intense. Writing to

Mr. Wilkes in 1830, he says—

“The grass is so

green and the pale blue sky so resonant with larks in the

morning, and the loud strong bridal chuckle of blackbirds and

thrushes at sunset, and the air so lovesick with sweetbriar, and

the garden so bright with hepaticas, and primroses, and violets,

and my transplanted trees dancing out so gracefully from my

broken clumps, and my leisurely evenings wearing away so

tranquilly, that they have passed in a sort of enchantment, to

which I scarcely remember anything exactly parallel since I

first left college in the same sweet season, to meditate on my

first love in my first ramble in the Highlands.”

When sweltering

under the heat of July in London in 1833, he writes to Cockburn—

“I wish I were

lolling on one of my high shady seats at Craigcrook, listening

to the soothing wind among the branches.”

And a week later,

writing from Watford, though he had been all day wandering among

the ancient Druidical oaks and gigantic limes of Moor Park, his

heart was still in his Scottish home. “It is sweet weather,” he

says, “and I pine hourly for shades, and leisure, and the Doric

sounds of my mother tongue.”

On his return

from the sunny south, he writes to Empson—

“I am agreeably

disappointed in this here Craigcrook. It is much less rough and

rugged and nettley and thistley, than I expected, and really has

an air that I should not be ashamed to expose to the gentler

part of polished friends from the south. It has rained a little

every day, but nothing to-signify, and there is a crystal

clearness on the steep shores of the Forth, and a blue

skyisliness on the distant mountains of the west, that at most

makes amends for your emerald lawns, and glorious woods of

Richmond and Roehampton.”

In the cold and

wet April of 1837 he describes himself to Rutherford as

“exercising a frugal and temperate hospitality at Craigcrook,

reading idle books, and blaspheming the weather and on 11th

November of that year he writes to Empson—

“Postremum hunc

Arcthusa—We go to Edinburgh to-morrow, and I shall indite no

more to you this year from rustic towers and coloured woods.

They have been very lovely and tranquil all day, and with no

more sadness than becomes parting lovers; and now there is a

glorious full moon looking from the brightest pale sea-green sky

you ever saw in your life.”

In 1835 he

completed the beauty and comfort of Craigcrook by making his

last and greatest addition to the house. “I am going to make an

addition to Craigcrook,” he wrote to Mrs. Colden, 29th April,

“and am pulling down so much of the house that I fear we shall

not be able to inhabit there this year.” On September 30th he

wrote to Dr. Macleod, “My Craigcrook buildings have been roofed

in for some time, and everything finished but the plastering.”

The enlargement

of Craigcrook enabled Lord Jeffrey to extend his hospitality,

and his letters show that he received frequent and often

lengthened visits not only from old friends like John

Richardson, but also from numerous individuals who had attained

high eminence in literature and science, in artistic, and even

military pursuits. Lord Cockbum mentions that on the 21st of

October 1837 he dined at Craigcrook with the veteran soldier

Lord Lynedoch, one of the finest specimens of an old gentleman;

his head finer than Jupiter’s; his mind and body, at the age of

eighty-eight, both perfectly entire; with a memory full of the

most interesting scenes, and people of the last seventy years.

It is pleasant to think of the eminent critic and judge

dispensing generous hospitality to such veterans as Lord Chief

Commissioner Adam and Lord Lynedoch, and to Macaulay, Talfourd,

and Dickens, along with his own personal friends Cockbum,

Moncreiff, Mackenzie, Fullarton, and Rutherford, and enlivening

the conversation with a play of fancy, wit, humour, shrewd and

sound sense rarely equalled.

Not less

interesting, though in a different way, is the picture of the

venerable judge sauntering in his garden or in his grounds,

hand-in-hand with his precocious little grandchild, explaining

to her the materials of her clothes, and the difference between

plants and animals; pointing out the goodness of God in making

flowers so beautiful; expounding the mysteries of numeration,

and the benefits to be derived from attendance at church. To

him, in these circumstances, we may apply with additional

interest the description which Burns gives of Sir Thomas Miller

of Glenlee, President of the Court of Session, at his beautiful

seat of Barskimming:—

“Through many a

wild romantic grove,

Near many a hermit-fancied cove,

(Fit haunts for friendship or for love),

In musing mood,

An aged judge, I saw him rove Dispensing good.”

In 1844 we find

him writing to Mrs. Empson describing his enjoyment in the

company of his eldest grandchild Charlotte, who was at that time

little more than four years old :—

“One other

Scottish Sunday blessing on you before we cross the Border; and

a sweet, soothing, Sabbath-quiet day it is, with little sun and

some bright showers, but a silver sky, and a heavenly listening

calm in the air, and a milky temperature of 67; with low-flying

swallows, and loud-bleating lambs, and sleepy murmuring of bees

round the heavy-headed flowers, and freshness and fragrance all

about. Granny [Mrs. Jeffrey] went to the Free Church at

Muttonhole, and Tarley and I had our wonted walk of speculation,

I showing her over again how the silk, and the muslin and the

flannel of her raiment were prepared; with how much trouble and

ingenuity; and then to the building of houses in all their

details; and to the exchange of commodities from one country to

another—woollen cloth for sugar, and knives and forks for wine,

etc.; all of which she followed and listened to with the most

intelligent eagerness. She then had six gooseberries of my

selection in the garden, and then she went up to Ali [a nursery

maid], I went to meet Granny on her way from the Free, whom I

found just issuing from it with the ancient pastor’s wife—the

worthy Doctor himself having prayed and preached, with great

animation, for better than two hours, in the eighty-second year

of his age. Soon after we came home Rutherfurd came up from

Lauriston, and we strolled about for a good while, when

Charlotte and I conducted him on his way back, and are just come

in at five o’clock. An innocent day it has been at any rate, I

think. ... It would do any heart good to see the health and

happiness of these children! The smiling, all-endearing, good

humour of little Nancy, and the bounding spirits, quick

sensibility, and redundant vitality of Tarley. ... I wish you

could see our roses, and my glorious white lilies, which I kiss

every morning with a saint’s devotion. We have been cutting out

evergreens, and extending our turf, on the approach; and it

looks a great deal more airy and extensive!*

Again, he wrote

to Mrs. Empson describing a walk which he and his granddaughter

had “all over the fields,” gathering a basket of mushrooms :—

“Our talk

to-day,” he said, “was of the difference between plants and

animals, and of the half-life and volition that were indicated

by the former; and of the goodness of God in making flowers so

beautiful to the eye, and us capable of receiving pleasure from

their beauty, which the other animals are not; and then a

picture by me of the first trial, flight, and adventures of a

brood of young birds, when first encouraged by their mother to

trust themselves to the air—which excited great interest,

especially the dialogue parts between the mother and the young.

She has got a tame jackdaw, whose voracity in gobbling slips of

raw meat, cut into the semblance of worms, she very much

admires, as well as his pale blue eyes. She was pleased to tell

me yesterday, with furious bursts of laughter, that I was an old

man, very old and was with difficulty persuaded to admit that

Flush (the true original old man) was a good deal older.”

In this dignified

and happy position, in the full enjoyment

“Of that which

should accompany old age,

Honour, love, obedience, troops of friends."

Lord Jeffrey

passed the closing years of his life. On the 9th of November

1849 he left Craigcrook for the last time. On that day he wrote

to Empson:—

“Novissimu hoc in

agro conscribenda! I have made a last lustration of all my walks

and haunts, and taken a long farewell of garden, and terrace,

and flowers, seas and shores, spiry towers, and autumnal fields.

I always bethink me that I may never see them again, and one day

that thought will be a fact; and every year the odds runs up

terribly for such a consummation. But it will not be the sooner

for being anticipated, and the anticipation brings no real

sorrow with it.’’

North Side

The consummation

was nearer than he anticipated. On the 22nd of January he was in

Court for the last time. He was then under no apparent illness;

insomuch that before going home he walked round the Castle Hill,

with his usual quickness of step and alertness of gait. But he

was taken ill that night of bronchitis and feverish cold, though

seemingly not worse than he had often been. On the evening of

the 25th he dictated the last letter he ever wrote to the

Empsons. He died on the evening of the next day, the 26th of

January 1850, in his seventy-seventh year.

“This event,”

says Lord Cockburn, “struck the community with peculiar sadness.

On the occasion of no death of any illustrious Edinburgh man in

our day was the public sorrow deeper or more general.”

“15 Great Stuart

Street, “Edinburgh, 27th November 1886.

“Dear Dr.

Taylor,—You have been good enough to ask me to furnish for your

intended book about Craigcrook my personal recollections of the

place, and of its celebrated occupant, Jeffrey.

“It is not always

easy to break down into intelligible or readable fragments a

general remembrance extending, as in this case, over the greater

part of a long lifetime. Neither is it easy to express in words

the emotions and associations which the theme you propose to me

calls up. I do not remember a time when it was not identified

with visions, growing more defined as age advanced, of interest,

brilliancy, and pleasure. Old Craigcrook, with its gray towers,

tea-roses, and its overhanging woods, is indelibly associated in

my memory not only with sunshine and flowers, but with the

sowing of the seeds in literature and politics, which produced

so plentiful a harvest. Time moderates many enthusiasms, and

reduces boyish idols to smaller proportions; but I have not

found it so in the present instance. In the course of my life I

have come in contact with many distinguished standards by which

my early admiration might be tested; and looking back through

more than sixty years, I still bow before the images I first

worshipped.

“But while the

vivid impression remains, single details become dim. I knew

Craigcrook as a child, as a schoolboy, and as a college lad. But

the men were, of course, my father’s friends, and not my own. It

was only after those periods had passed that I could pretend to

have observed cotemporary events on any footing of intimacy. In

token of our long friendship, and memory of past kindness, I

very gladly comply with your request, but I think I can only

discharge the task I have undertaken by simply putting down,

almost at random, some thoughts and recollections which your

request awakens. They will insensibly take the form more of

reflection and dissertation than of reminiscence, and I shall

confine them entirely to Jeffrey and his cotemporaries.—Believe

me, yours very sincerely, Moncreiff.”

Posterity is

generally just in its awards, but they constitute only average

justice, and not unfrequently individual injustice. I doubt if

the popular estimate is as high as it ought to be of what we owe

to the circle of vigorous and accomplished men, of which Jeffrey

was throughout the centre, and Craigcrook for long the

muster-ground. Men who have given a great impulse to human

thought, and have left indelible marks on intellectual progress,

are apt to be judged, especially in the next generation, more by

the standards they have themselves created than by those which

they abolished. The true measure of the claims of such men to

grateful remembrance can only be attained by comparing the

condition in which they found the current of national thought

with that in which they left it—by estimating the obstacles

which they encountered and surmounted, the dead weight which

their leverage removed, and the thick mists of ignorance and

apathy which in the end their exertions dissipated and

dispersed.

The Edinburgh

circle, of whom I now speak, have been described by Henry

Cockburn, one of the most distinguished of their number, in the

vivid and graphic style of which he was so great a master. They

were for some years a circle apart in the northern metropolis,

herding with each other, and visiting, dining, and taking their

recreation together. Politics ran very high in the beginning of

this century; and as these men were of the unfashionable school

of Fox, there was little social intercourse between the rival

armies. When I first began, with schoolboy eyes, to look out on

the world of Edinburgh, twenty years afterwards, the party

organisation was as stringent as ever; and although the ramparts

were gradually broken down, it required ten years more, and the

first Reform Bill, to complete the change. The rising

generation, however, happier than their predecessors,

disregarded in social life the old lines of separation, and many

of them found, as I did, some of their fastest and truest

friends in the opposite camp.

The original

fraternity was composed of a knot of college lads— they were

hardly more—who came together in Edinburgh in days when the

French Revolution had stimulated thought all over Europe, and

when the avidity for the acquisition of knowledge was intense.

They had for the most part been associated within the walls of

the Speculative Society of Edinburgh, a Debating Club of some

fame which has a certain University sanction. At the beginning

of this century many of them had been drafted off into various

lines of life. Most of them went to the Scottish Bar; some of

them, more ambitious, tried their fortune at that of England;

some joined the ranks of Science; but all in the end made their

mark, and not a few with distinguished success. The names of the

most eminent were Francis Jeffrey, Henry Brougham, George

Cranstoun, James Moncreiff, Francis Horner, and his brother

Leonard, John Playfair, Henry Cockburn, Thomas Thomson, John

Allan, John Fullerton, John Archibald Murray, and a young

English clergyman of the now famous name of Sydney Smith. To

these I should add the names of George Joseph Bell, John

Playfair, John Leslie, Dugald Stewart, Thomas Brown, and John

Richardson. They were all friends of my father’s; and my

grandfather, old Sir Harry Moncreiff, was never better pleased

than when any of this young and vigorous band came, as they

often did, to join his supper-party.

Of the men whose

names are included in this list, the after career was

remarkable. When the Edinburgh Review started in 1802, Sydney

Smith was the eldest of the band, being in his thirty-first

year. Jeffrey was thirty, and Brougham and Cockbum, I take it,

were the youngest, being twenty-four. In the end not one of

those I have named failed to rise to honour. Brougham became

Lord Chancellor, and for a time the arbiter of the political

world. Homer, dying at forty-one, was the subject of a

resolution in the House of Commons, moved by Canning, expressive

of the regret felt at his decease. Sydney Smith, although he

never attained the more glittering prizes of the Church,

acquired fame enough to have satisfied the most ambitious. Of

the Edinburgh section, although they belonged for many years to

the proscribed side of politics, Cranstoun, Fullerton, Moncreiff,

Jeffrey, Cockbum, and Murray rose to the Scottish Bench, after

having for many years absorbed a large proportion of the leading

practice, and after occupying a prominent position in politics.

Jeffrey and Murray both held the position of Lord Advocate, and

Cockbum was Solicitor-General for some years. Of those in other

intellectual pursuits, the names of Dugald Stewart, Thomas

Brown, John Playfair, and John Leslie stood, and still stand, as

high as Science or Philosophy can raise their votaries.

Such was the

Brotherhood. They were not all contributors to the Review.

Cranstoun and Moncreiff devoted themselves to legal practice, to

the high rank in which they both soon attained. I find from a

letter of Jeffrey’s in 1804 that he had endeavoured to enlist

Cranstoun for the Review, but had failed to induce him to join.

He seems to have had a high estimate, and rightly, of

Cranstoun’s general accomplishments, but his vows had been paid

to his profession, and he was averse to divert his

South Side

attention from

it. He was a year or two older than the others, was of good

family, and had at one time thought of entering the army. I had

the good fortune to visit him on two occasions at his seat at

Cora House, on the Clyde, a most beautiful and remarkable spot,

and not more distinguished than its proprietor. He was a

courtly, somewhat reserved, formal and fastidious man, but when

he unbent was full of resources, varied knowledge, learning, and

familiarity with the world.

Of my father I

need not speak here. The quiet and unassuming force of his

character was known throughout all Scotland. His powerful grasp

of legal reasoning made him the most distinguished pleader of

his time at the Scottish Bar, and his recorded judgments on the

Bench are an imperishable monument to his judicial ability. Lord

Cockbum says of him that his name among the Brotherhood was,

“The Whole Duty of Man.” I think it was well bestowed: he was

the best man I ever knew. It was the fashion among them to say

that he was devoted to his profession, which in truth he was,

knowing that to be the only talisman to ensure success, and

having genuine pleasure in the dialectic exercise. In the end he

reached a mastery in the Art which few ever attained. He had,

besides, an intensity of energy which never flagged, and which

served him in great things as well as in small. But he had other

tastes—not suspected of any but his intimates. He was

exceedingly fond of music, and no mean judge of it. It was a

taste which, I think, few of the others shared with him. He was

an ardent politician, apart altogether from all notions of

personal interest; and although as far removed from the Radical

ranks as a follower of Fox could be, I believe he thought the

early numbers of the Review not true blue enough for his

standard. Latterly, I think, a seat in the House of Commons was

the real object of his quiet and unexpressed ambition. He felt

that he had so full a knowledge of the commercial and

agricultural interests of Scotland, and was so conversant with

its affairs, that he might be of some practical utility in that

position. But those were only castles in the air. He had been

raised to the head of the Scottish Bar by his election as Dean

of the Faculty of Advocates in 1826. In 1829 he accepted a seat

on the Bench, which he had been offered and declined two years

before. Had he foreseen that the political sun was about to

shine on the Whig side so soon, it is not improbable that he

would have continued longer at the Bar. A third characteristic

was a love of athletics and field sports. Grouse-shooting,

dog-breaking, feats of walking and running, were common topics

in his after-dinner talk with us, and in his later years he was

often seen as a spectator on the cricket-ground. General

Hutchinson, in his Book on Dog-Breaking, mentions a dog-story

told him by my father at his own table, where the General was a

welcome guest. In his youth (in his Oxford days) Lord Moncreiff

was a renowned pedestrian. He and Sir John Stoddart, who was

afterwards his brother-in-law, once walked from Edinburgh to

London for amusement. I think they were twelve or fourteen days

on the way, exclusive of two days spent with Wordsworth at the

Lakes. Stoddart was a German scholar, which Moncreiff was not,

and he found, I think, the two days of Goethe and Schiller the

most fatiguing of the fortnight.

He was always a

great favourite with the circle, and with Brougham, Jeffrey, and

Cockbum in particular; and they looked upon each other with the

eyes of affectionate schoolboys. His simplicity, want of

self-assertion, and manly truth and straightforwardness,

attracted them; and they respected although they did not always

sympathise with the earnestness which was his characteristic. It

might have been well, perhaps, if some of it had been

transferred. With Brougham his friendship and correspondence

continued unbroken to the end. In 1834 he spent a fortnight at

Brougham's house in London while the latter was Chancellor. I

accompanied him to London, and during that period I met Jeffrey

and Brougham at dinner at the house of Dr. Maton, who was then

the Court Physician. The party, as far as I recollect, consisted

of Brougham, Jeffrey, Sir Benjamin Brodie, Lord Moncreiff, and

myself. It was an interesting dinner-party. The talk was very

good, Brougham was rather voluble, and Jeffrey not as much so as

I have known him; but it was an evening to remember.

On Henry Cockbum,

better known now as Lord Cockbum, I shall not enlarge. I did

once attempt to estimate his character and services as a

testimony not more of gratitude than of admiration. What I owed

personally to his constant and persistent friendship I cannot

express, and I only pass his name now that I may not be diverted

from my present theme. His ability was equal to that of any of

the circle, and he had in addition the rare gifts of originality

and genius.

None of the

others, as far as I know, excepting Cockbum, took any interest

in field sports or athletics, or open-air pursuits of any kind.

A quiet game at bowls was the utmost exertion which served for

amusement. Cockbum had one accomplishment certainly which argued

athletic training and power: he skated beautifully. To witness

the Judge’s graceful figure, with the sweep of his measured

dignified outside edge, looking like the monarch of the ice, was

a sight worth remembering. One bright frosty Saturday I remember

well, when Lochend was frozen to its core with a thick

transparent cover, showing the weeds bending below. I was

pleading a case before Patrick Robertson (Lord Robertson), when

Lord Cockbum appeared at the back of the bench, and this

dialogue ensued:—

Cockburn : You

must let Moncreiff off for to-day. He and I have a meeting of

trustees to attend.

Peter : Who are the trustees?

Cockburn : Loch’s trustees.

Peter : Where do they meet?

Cockburn : At Lochend.

Peter: Oh!

We attended the

meeting, and years afterwards I was shown a letter from Cockbum

to a correspondent which he had written on the following day, in

which he described our skating, and said, “We careered like

angels upon an inverted sky,” an association of which I was

proud but unworthy.

Of all the

circle, Cockbum had the most influence with Jeffrey, and was

nearest his everyday life, although from obvious causes this

does not come out in Jeffrey’s correspondence. For the most

part, Cockbum was at hand. In his editorial work he was not the

man to bring his name into prominence; but in the Craigcrook

festivities, the Saturday’s Saturnalia, as they were called, few

were organised without Cockbum’s aid. He arranged the bowling

parties, and very often chose the guests. Thus we find Jeffrey

writing in 1827 to Cockburn : “Pray dine here on Thursday,. . .

and ask Thomas (Thomson) and the Rutherfurds, and any others you

think worthy.” And in 1828 be laments Cockbum’s absence. He

says, “Cockburn has deserted us more than usual; first, for his

English friends, and then for those in the North, having been a

week or more with the Lauder Dicks, and passing twice by

Rothiemurchus.”

My old

grandfather, Sir Harry Moncreiff, was a powerful and

characteristic man, and much appreciated by those younger

lights. He had been a man of mark almost before most of them

were born. A man of strong, self-reliant capacity, of large

views and sympathies, and known to high and low from one end of

Scotland to the other. His encouragement to the rising Whigs of

the younger generation did not a little to promote the

confederacy which afterwards became so powerful. I knew him very

well, as far as a lad of fourteen could know a man of

seventy-six; for during the two last years of his life, when his

footsteps had grown feeble, he used me as a walking-stick, and I

had the advantage, which I have ever since valued, of his

interesting and powerful conversation. He was a kind of landmark

for the Whig party in the North.

Cockburn has

sketched him very faithfully, and in Jeffrey’s letters we find

him referred to once and again in terms which indicate both

respect and intimacy. Thus, in 1811, during the Grey and

Granville negotiation, we find Jeffrey rejoicing over the party

prospects. He says: “Our Whigs here are in great exultation, and

had a fourth more at Fox’s dinner yesterday than ever attended

before. There was Sir H. Moncreiff sitting between two

Papists!—and Catholic emancipation drank with great applause—and

the lamb lying down with the wolf—and all millennial.”— 25th

June 1811. Sixteen years afterwards, in August 1827, we find him

again mentioned: “Alas! for poor Sir Henry and ancient Hermand

[they died on the 9th August 1827]. It is sad to have no more

talk of times older than our own, and to be ourselves the

vouchers for all traditional antiquity. I fear, too, that we

shall be less characteristic of a past age than those worthies

who lived before manners had become artificial and uniforms and

opinion guarded and systematic.” He says further on: “I wish I

could summon up energy enough to write a panegyric on old Sir

Henry; and if I were at home, I think I should. But I can do

nothing anywhere else.” But what Jeffrey meditated, Brougham

did; and devoted a paper in the Edinburgh Review in January 1828

to this tribute of kindly remembrance.

Some, or rather

most of the others, I knew familiarly in after life, but they

had scattered before I took part in the world’s affairs. I never

saw Horner. He and Brougham went to London about 1805 or 1806.

Playfair died in 1815, and Homer in 1817. From Brougham I had

much kindness in after years, and his close friendship with my

father never abated. Leonard Homer migrated later. He and his

family are among my earliest and brightest recollections, and

his house in Lauriston Lane in Edinburgh was the scene of the

gayest and noisiest of children’s parties, which still retain

the glorified remembrance of childish or boyish years.

Jeffrey, writing

from London in 1823, says, “I was surprised this morning to run

against my old friend Tommy Moore, who looks younger, I think,

than when we met at Chalk Farm some sixteen years ago.” And-in a

subsequent letter in May of the same year, he says, “I also saw

a good deal of Miss Edgeworth and Tommy Moore,” and goes on to

say that “Moore is even more delightful in society than he is in

his writings.” I refer to these things, because they recall some

of the phantoms of my youth. Moore was in Edinburgh either in

that year or the next. I never saw him, but I well recollect my

father and mother going in 1824 to dine with Sir Harry on an

occasion to which they seemed to attach unusual interest. It was

to meet two rather incongruous guests—Tom Moore and Dr. Andrew

Thomson, then the most popular Evangelical preacher in

Edinburgh. I recollect that they returned delighted. Tom Moore

and Thomson fraternised at once. The bond of union was their

passion for music. Moore had sung several of the Melodies; and

Andrew Thomson, who had a fine voice, and was an accomplished

musician, had finished the evening by singing Moore’s song of

the “Meeting of the Waters.” The party embraced, I am told,

Chalmers, Jeffrey, and old Henry Mackenzie.

Miss Edgeworth,

too, is one of these shadowy apparitions. I was once told off

about the same year—1823 or 1824—to escort her to the Went

Church in Edinburgh to hear Sir Harry preach, and I well

remember the kindly charm of her manner. About the same time and

in the same place I encountered Sir James Mackintosh. As I was

much impressed with the dignity of my position on these

occasions, being greatly overawed by the celebrity of my

companions, I fear that as I sat opposite to them in the square

pew in the West Church, I never took my eyes off them; not much

to the credit of my good manners, but I learned the features of

these famous ones by heart. I never saw either again.

Drawing Room

One of the

original Brotherhood, and one of the first to yield to the

attraction of London, was John Richardson, a man whose mind was

cast in a gentle and poetic mould, but who was for many long

years the Crown Solicitor in Scottish affairs in London, and a

most able and efficient administrator. It was after most of

those whose names I have recounted had departed that I became

intimate with him, and a more charming companion, or a

pleasanter circle than that which he collected round him in

London, I never knew. He had an attractive vein of the poetic

running through the whole strain of his genial conversation; and

in the quiet evenings I have spent with him I learned more of

the early ways and characteristics of the “Order” than from any

other source. He was a great friend of Campbell the poet, and I

find in Jeffrey’s correspondence a letter which Jeffrey wrote to

Campbell with reference to Richardson’s leaving Edinburgh (p.

52, 17th March 1801). Among many other notable incidents at his

house in London, I have a vivid recollection of one occasion on

which Carlyle and Lord Chancellor Campbell were of the party,

and engaged in an interesting and well-sustained, though

courteous, single combat on the merits of the Lives of the

Chancellors. Sir David Dundas was also present, and from time to

time slyly fomented the conflagration. We thought that the

Chancellor, on the whole, had the best of the encounter.

But, like others,

Richardson had other tastes nearer his heart than business, or

poetry, or London. A trouting-rod by the banks of the Teviot or

the Ale was what he yearned for and enjoyed, and at his

beautiful property of Kirklands, in Roxburghshire, he had what

he prized more than all the projects of ambition.

These were the

men, some of them known to the larger world, and some less so,

but they were all in the front rank in the North. Scotland at

that time may have been regarded as provincial by those other

side the Tweed; may have been thought so then, and some

benighted Southrons may think so still. But at that day it was

in some respects less provincial than at present, and in some

respects more cosmopolitan than England. There may be some in

the present day who prate of nationalities, but they are few and

underbred. There is no doubt, however, that nothing contributed

so much to enhance the respect paid to Scotland among English

politicians and scholars as the success of the Edinburgh Review.

The circle which

I have described was for the most part forensic, but yet the

band ranged over the whole field of human knowledge in all its

branches. They had extensive reading, fair scholarship, some of

them were profoundly versed in the ancients, and Playfair,

Leslie, and Brougham were great and formidable representatives

of physical science, as Dugald Stewart and Thomas Brown were of

mental philosophy. I doubt if in the circuit of the British

Isles at that day there could have been found fifteen personal

intimates who presented such a combination of knowledge and

intellectual power.

Some critics, who

constantly assure the world that they are the true aesthetes,

while often they have not a ray of the diviner flame, have a

fashion of sneering at the magnates of the Edinburgh Review, as

if they had done nothing. I only know that in their society

these cavillers could not have held their place for a moment.

Their farthing candles would at once have been extinguished, for

those men were not dreamers over fanciful emotions, but were

stored with the results of hard and varied study. Those were

days in which conversation was an art, and I do not believe it

was ever more successfully cultivated than in that remarkable

circle. Of course, it was long after the date of which I write

that I can speak from personal experience; but I do remember one

bright summer evening, at a date when those feelings of

political separation had long since disappeared, when at the

hospitable board of Lord Mackenzie, the son of The Man of

Feeling, and a man of remarkable cultivation, we sat till the

shadows lengthened, while our host and Jeffrey discussed, with

amazing vivacity, wit, and eloquence, the dramatists of the

Elizabethan era. Whether in the present day it would have been

accounted slow, I cannot say; but we, a party of eight or ten,

were all sorry when it ended; and a greater wealth of

illustration, fancy, and acute appreciation than the dialogue

displayed, I have never found elsewhere. They did not harangue

or “orate,” as our American friends have it, or strive for the

lead, or seem to request any one to listen, but played into each

other’s hands, as if the exercise had been a delight to them.

Mackenzie, for the most part, started each view and topic,

Jeffrey caught it up and covered it with flowers. Indeed,

versatile as Jeffrey was in all departments of intellectual

exercise, his special attributes were best displayed in his

conversation. Instinct with a vivid fancy rather than with

imagination, and a rapid incisive wit rather than humour, his

talk was such that one could not listen to him and mark the

fertile suggestions of his mobile brain without admiration. One

of the last occasions on which I was in his company was in a

walk with him alone from Craigcrook to Edinburgh, a distance

under three miles, through the grounds of the old residence of

Ravelston. It was a few months before his death. What he talked

of, I cannot recollect; I only know his discourse was wonderful,

and full of melody, instruction, and wisdom.

When I came to be

intimate in his later years with this truculent Minos, he was

the gentlest, kindest, and most considerate of men. Years of

success and fame may have tempered the outspoken vivacity of his

manners, and smoothed over the rough edges of his speech or

thoughts, but as I knew him, and as many others had the best

reason to know— though some did not always remember—he was full

of warmth, of feeling, and of generosity. He had no jealousies

and no antipathies, and neither open spite nor covert detraction

could find endurance at his hands, whoever the author and

whoever the object of them.

In the light of

retrospect no one can fail to see that the commencement of the

Edinburgh Review marks an epoch in periodical literature as

clearly as did The Toiler and The Spectator in their day.

Periodical journalism, devoted in the main to criticism, is

necessarily ephemeral in its nature. It is meant for the present

reformation of literary taste; and when it has done its work,

and literary taste has been so completely reformed that the old

corruptions are forgotten, no wonder that the critic appears at

the distance of three-quarters of a century to be a trifle

commonplace and a mere beating of the air. The real question is,

Did it do its work? And that it did in this instance is

unquestionable, or that journal would never have acquired the

astonishing celebrity which it at once commanded.

It is thus merely

idle for feeble minds to decry Jeffrey’s literary judgments as

being erroneous. They were addressed to the public of 1803, and

the public of 1803 were perfectly able to judge of them,

probably much better than some of the public of 1886. They did

substantially approve them, to the extent of buying the Review.

Some of our modem scribes are never tired of cavilling at

Jeffrey’s strictures on Wordsworth, Coleridge, and what were

called the Lake school. I do not say that Jeffrey fully

appreciated the merits of those men, or may not have been too

severe on their unquestionable faults. They had the genius, as

all the world now allows. Poetry of the emotions, poetry of

feeling, not of action, poetical analysis of the inner

consciousness, was of a style to a certain degree not familiar

in those days to our countrymen, and I think not congenial to

Jeffrey’s cast of thought. The school had a German mystical

dreamy element which the great critic too much resented, and the

want of masculine vigour which seemed to characterise it threw

into the shade with him the real depth, pathos, and truth of its

delineations. Addison and Steele and Swift and Johnson were as

often wrong as right in their estimate either of literature or

of manners, but no one on that account denies them their places

as pioneers in the literary progress of the nation. Jeffrey was,

of course, not infallible, but he stirred the public mind to

solve great problems in literature and politics, and few men

have done as much, and still fewer have done or can do more.

Nor am I by any

means prepared to concede that Jeffrey’s criticisms on the Lake

school, although imperfect and to some extent misleading, were

entirely erroneous. I do not think that they were so in

themselves, or as regarded the effect of these writers on the

national literature. That the poets had genius, and rare genius,

is certain, but their real fault was affectation—affectation of

simplicity, and affectation of mysticism. I know this will be

considered heresy. But what has been the result of the reaction

which they led?—that poetry has in great measure ceased to be

written, and that what has been written has to a large extent

ceased to be read. Readers have grown tired of groping about to

find an unexpressed meaning in unmeaning words, and decline to

accept spasmodic and ambiguous utterances as indicating any

inspiration. I except the Laureate, who may have his own sins to

answer for, but he has the true inspiration, and can be manly

when he chooses.

I was in my

younger days a diligent student of the earlier numbers of the

Edinburgh Review. I found them a repertory of vivacity, of

vigour, and of intelligence. I learned from them many lessons,

which I have found of service in my subsequent life. I am glad

to find that the appreciation which I then had is confirmed by a

great name, which even the most critical can hardly disparage.

Macaulay says in a private letter, just before the collected

reviews of Jeffrey were published: “Jeffrey is at work on his

Collection. It will be delightful, no doubt, but to me it will

not have the charm of novelty, for I have read and re-read his

old articles until I know them by heart.” And he says in a

subsequent letter: “What do you think of Jeffrey’s book? The

variety and fertility of Jeffrey’s mind seem to me more

extraordinary than ever. I think there are few things in the

four volumes which one or two other men could not have done as

well. But I do not think that any one man except Jeffrey—nay,

that any three men—could have produced such diversified

excellence. When I compare him with Sydney and myself, I feel

with humility perfectly sincere that his range is immeasurably

wider than ours; and this is only as a writer. But he is not

only a writer, for he has been a great advocate, and he is a

great judge. Taking him for all in all, I think him more nearly

a universal genius than any man of our time.”

With the view of

renewing my Craigcrook associations, and recalling some minor

traits which my memory had let slip, I have re-read the whole of

Jeffrey’s letters, at least those published by Cockburn, which

must be but a minute fraction of those he wrote. I found it a

very interesting and very instructive occupation. His letters

tell the story of his life in very clear outline. They bring out

the rapid brilliancy of his thoughts very perfectly, as well as

the kindly courage and sweetness of his temper. One element is

disclosed which in my knowledge of the man I had not detected or

expected. There was a tinge of melancholy running through the

golden thread of his genius, arguing a depressed and nervous

temperament, even when fame and fortune favoured him most.

Prosperity did not mark him for her own for some tedious years

after he joined the Bar, and the death of his first wife left an

element of sadness which not unfrequently recurs. His earlier

life at the Bar was not at once successful or cheerful; at

least, as often happens, the consciousness of unappreciated

power seemed, if he may be judged by his correspondence, to

produce a chronic depression, deepening as the years went on.

But this is a phase from which few successful lawyers have been

free. We find him, after two or three years had passed,

beginning to wonder if he had mistaken the bent of his

intellect, and full of schemes, some of them wild enough, for

making a new start.

Dining Room

Thus in 1796 he

says: “I wish I had learned some mechanical trade, and would

apply to it yet, were it not for a silly apprehension of silly

observation. At present I am absolutely unfit for anything, and

with middling capacities, and an inclination to be industrious,

have as reasonable a prospect of starving as most people I

know.”

Again, on 6th

March 1799 he says: “As to the goods of fortune, I can say but

little for myself. I have got no legacies and discovered no

treasures since you went away, and for the law and its honours

and emoluments, I do not seem to be any nearer than I was the

first year that I called myself practitioner.” On the 3rd

January 1801, he writes to his brother: “I make but little

progress, I believe I may say none at all, at the Bar; but my

reputation, I think, is increasing, and may produce something in

time.” And again, on the 1st of August 1801: “I do not make a

hundred a year, as I have told you, by my profession.”

But with the

assured success of the Review these apprehensions as to his

worldly prosperity vanished, and as his literary fame grew, so

did his professional success. In 1807 he writes: “I write at the

Review still, and might make it a source of considerable

emolument, if I set any value on money. But I am as rich as I

want to be, and should be distressed with more, at least if I

were to work more for it.”

The tale of the

Edinburgh Review, its inception, its instantaneous success, the

struggles to maintain a reputation so rapidly gained, and the

strong broad flood which in the end swept so steadily on, may be

discerned in these letters, which formed but a fragment of his

current thoughts after all. The original projectors were

certainly Brougham. Jeffrey, and Sydney Smith, and the last

claims, I have no doubt justly, the credit of the original

proposition. Sydney himself tells the secret without disguise,

and the motto which he proposed for the work, which is too well

known to be quoted, affords real evidence of the truth of his

claim. I think I have heard my father say that Brougham did not

contribute to the two first numbers, although he was

unquestionably one of the original projectors. Sydney Smith

edited the first number, and then he left for London, and

Jeffrey ascended the throne which he held for so many years. It

was not a bed of roses, for one by one his comrades left

Edinburgh. In a charming commination which he directs against

Homer in 1805, and against all evil-doers of the same class, we

have, under his own hand, a list of the faithless ones. He says,

“If you will not write reviews, I cannot write anything else.

This number is out, thank Heaven! without any assistance from

Homer, Brougham, Sydney Smith, Thomas Brown, Allen, Thomson, or

any others of those gallant supporters, who voted their blood

and treasure for its assistance.” But although absent from the

headquarters of the Review, Brougham, Homer, and Sydney Smith

continued to be frequent contributors to the end of their lives.

Reading over the

memoirs of those remarkable men, one cannot help being struck by

the tone of affection, and often tenderness, which prevailed

among them. Jeffrey wails over the impending dissolution of

their circle in 1802, and will not be comforted. Sydney Smith’s

newborn babe was purloined by him from the nurse, in order to

show it to Jeffrey and the Edinburgh Reviewers. Smith often

recurs to the old faces and supper parties of his Edinburgh

companions, and actually goes so far as to wish that he had been

born a Scotsman, “to have people care so much about him,” as he

says.

On the other

hand, Jeffrey’s affection for him was maintained to the last. He

says of him, writing in 1827 to his sister in New York: “He is

the gayest man and the greatest wit in England; and yet, to

those who know him, this is his least recommendation. His kind

heart, sound sense, and universal indulgence, making him loved

and esteemed by many to whom his wit was unintelligible.”

There can be no

doubt it was the accident of Smith’s visit to Edinburgh in 1798

which led to the suggestion of the Review. In May 1802 Jeffrey

writes: “Our Review has been postponed until September.” And

then he adds: “Few things have given me more vexation of late

than the prospect of the dissolution of that very pleasant and

animated society in which I have spent so much of my time for

these last four years. And I am really inclined to be very sad

when I look forward to the time when I shall be deserted by all

the friends and companions who possessed much of my confidence

and esteem.” But the colour of his thoughts changed rapidly

after the first number of the Review was published at the end of

1802. Such was its instantaneous success that he could write to

Homer in May 1803, speaking of Longman’s terms, “The terms are,

as Mr. Longman says, ‘without precedent;’ but the success of the

work is not less so.” From this time the triumphant march is

unbroken. Much discord, no doubt, the pungent pages made

throughout their literary victims, and many and murderous were

the threats launched against the aggressors, although “Little’s

leadless pistol” was the nearest approach to bloodshed, and the

not too deadly English Bards and Scotch Reviewers the most

effective retaliation. It is singular, and concludes the romance

fitly, that in both instances the incensed combatants ultimately

vowed eternal friendship, Moore finding in Jeffrey his bosom

companion, and poor Byron at the other end of Europe wishing he

were drinking his claret with Jeffrey at Craigcrook.

For such was the

bright and sunny goal to which all these events had tended. It

was in 1815 that Jeffrey first set up his household gods at

Craigcrook. At that date he had defied and conquered fortune—not

indeed without a struggle or without wounds. His practice

advanced steadily until the introduction of trial by jury in

civil causes in Scotland. Under that system he from the first

assumed and held a commanding position. His brilliant rhetoric

found in that branch of practice an outlet not afforded by

procedure in ordinary legal questions. He says himself in a

letter written, I think, in 1815: “We are getting jury trial in

certain civil causes too, and that will give me more work. You

must know I am a great juryman in the few cases that are now

tried in that way, and got a man off last week for murdering his

wife, to the great indignation of the Court and discontent of

all good people.” But in the ordinary work of the Courts his

fame as a pleader stood in the first rank.

One reflection as

I went over this correstimepondence struck me forcibly, that as

the greater extent of reading has been the destruction of the

art of conversation, so the penny postage and the telegraph have

terminated the art of letter-writing. There was much virtue in

the time, which was the price at which the glory of a London

letter was to be had among us in former days, and the writer

always tried to give value for the money in painful crossings

and re-crossings. Jeffrey’s correspondents had a still greater

trial in his handwriting, of which he used to say that he had

three kinds—one which his friends and the printer could read,

one which the printer could read but his friends could not, and

the third class completely illegible to both. In May 1822

Jeffrey was desirous of a visit from Sydney Smith, and wrote to

him to invite him to come. Sydney’s reply was, “We are much

obliged by your letter, and should have been still more so had

it been legible. I have tried to read it from left to right, and

Mrs. Sydney from right to left, but neither of us can decipher a

single word of it.” Nevertheless, the task of deciphering

Jeffrey’s letters was generally amply repaid by the contents. We

shall never see such letters again—lively, affectionate, full of

strong feeling, lighted up with gleams of fancy and merriment,

and a crisp, concise succession of sentences. They have all the

qualities which letters ought to have, and which in the old days

they sometimes had.

It is interesting

to trace through the correspondence the transition of this man

of rather depressed temperament from disappointment to

success—from a failure to a hero. It is rather like Carlyle’s

description of Cromwell mournfully meditating on the banks of

the Ouse, not dreaming how great a man he was to be. The

widespread reputation of the Edinburgh Review spread also that

of its editor; and accordingly we find him, in the first glimpse

we have of him in London in 1811, free of the best and most

exclusive circles in the metropolis, and alongside of the most

renowned men of the day. He writes on the 12th May 1811: “Came

home rather late for dinner, and went to Nugents (a great

traveller), a brother of Lord N-, where we had an assemblage of

wits and fine gentlemen—our old friends Ward and Smith, and

Brougham and Mills, who threatened to be Chancellor of the

Exchequer last year, and Brummell, the most complete fine

gentleman in all London, and Luttrell, and one or two more.”

He goes on to

describe how he spent the evening at Holland House, and the

magnates he met there, including the old Duke of Norfolk. We

find him again in London in 1817, when he writes: ‘ I saw a good

deal of Frere, and a little of Canning; neither of whom appeared

to me very agreeable, though certainly witty and well bred.

There is a little pedantry, and something of the conceited

manner of a first form boy, about both.” He says he met Burdett

once or twice, but was not impressed by him; and he adds:

“Tierney is now the most weighty speaker in the House of

Commons, and speaks admirably for that House; Brougham is the

most powerful, active, and formidable; Canning is thought to be

falling off, and certainly has the worst of it in all their

encounters.” This letter was written a few weeks after the death

of Homer at Pisa, and of him Jeffrey says: “It is really

impossible to estimate the loss which the cause of liberal and

practical opinions has sustained by this death. I, for my part,

have lost the kindest friend, and most exalted model, that ever

any one had the happiness of possessing. This blow has quite

saddened all the little circle in which he was head, and of

which he has ever been the pride and the ornament.”

I set down these

few words of Jeffrey, because they could not have been used by

him of any man not acknowledged to be in the front rank in the

intellectual and political world. That Francis Homer was

eminently so, every one knew, but there has been an unworthy

tendency among the ignorant of his countrymen to undervalue his

services. I am very much tempted to prolong this analysis of

Jeffrey’s London life, in which he met many of the most

distinguished men of the day, and met them on a footing of

perfect and complete equality. There is scarcely a man of

eminence whose name does not occur in these letters. But I shall

content myself with only two further extracts. The first is a

very vivid account of a man of great celebrity, of whom perhaps

less has been said than he deserved,—I mean Lord Althorpe,

afterwards Lord Spencer, who led the House of Commons during the

days of the first Reform Bill. On 12th February 1832, Jeffrey,

writing to Lord Cockbum, says: “I dined yesterday at Lord

Carlisle’s, and to-day at Lord Althorpe’s. . . . Althorpe, with

his usual frankness, gave us a pretended confession of faith,

and a sort of creed of his political morality, and avowed that

though it was a very shocking doctrine to promulgate, he must

say that he had never sacrificed his own inclinations to a sense

of duty without repenting it, and always found himself more

substantially unhappy for having exerted himself for the public

good! We all combated this atrocious heresy the best way we

could; but he maintained it with an air of sincerity, and a

half-earnest, half-humorous face, and a dexterity of statement

that was quite striking. I wish you could have seen his beaming

eye and benevolent lips kindling as he answered us, and dealt

out his natural familiar repartees with the fearlessness as if

of perfect sincerity, and the artlessness of one who sought no

applause, and despised all risk of misconstruction; and the

thought that this was the leader of the English House of

Commons—no speculator, or discourser, or adventurer—but a man of

sense and business, and of the highest rank, and the largest

experience both of affairs and society. We had also a great deal

of talk about Nelson and Collingwood, and other great

Commanders, whom he knew in his youth, and during his father’s

connection with the navy; and all of whom he characterised with

a force and simplicity which was quite original and striking. I

would have given a great deal to have had a Boswell to take a

note of the table talk; but it is gone already.”

Morning Room

I conclude this

part of my reflections by an extract from a letter written after

he had gone on the Bench. There is a tone of repose and

satisfaction in the account he gives of his London life. He

says: “Our old friends have been very kind to us, and I go away

confirmed in my purpose of spending a little time there (London)

every spring. Being there for the first time without any serious

task or occupation, I entered more largely into society than it

was easy for me to do before; and, at all events, crowded into

these five weeks the sociality of a whole long session of

Parliament. I had the good luck, too, to come at a very stirring

time, and to witness the restoration to power of a party to

which I was attached so long as it was lawful for me to belong

to a party. From the height of my judicial serenity I now affect

to look down on those factious doings, but cannot, I fear, get

rid of old predilections. At any rate, I am permitted to

maintain old friendships, and to speak with the openness of