|

The

author attributes the claimed migrations of the Irish into Argyll to

a set of elite origin myths finding no support in archaeological

evidence. He goes on to ask how the Iron Age populations of Argyll

established and changed their personal and group identity.

Traditional historical accounts of the origin of the Scotttish

kingdom states that the Scots founded the early kingdom of Dal

Riata in western Scotland having migrated there form north

eastern Antrim, Ireland. In the process they displaced a native

Pictish or British people from an area roughly equivalent to modern

Argyll. Later, in the mid 9th century, these Scots of Dal Riata

took over the Pictish kingdom of eastern Scotland to form the

united kingdom of Alba, later to become known as Scotland. To

the classical authors of late antiquity, the peoples of Ireland were

Scotti, probably a derogatory term meaning something like

'pirates'. The name was used by early medieval writers in Latin for

all speakers of Gaelic, whether in Ireland or Scotland. Much later

the usage became associated exclusively with the peoples of

Scotland, whether speakers of Gaelic or not. In this paper I will

use the term Goidelic for the Irish/Scottish Gaelic, branch of

Celtic (Q-Celtic), and Brittonic for the British group including

Welsh, Pictish and Cumbric (P-Celtic).

After a

period of virulent sectarian debate on the origins of the Scots in

the 18th and 19th centuries (Ferguson 1998), the idea of a

migration of the Scots to Argyll has become fixed as a fact in both

the popular and academic mind for at least a century. Present-day

archaeological textbooks show a wave of invasive black arrows

attacking the west coast of Britain from Ireland in the late 4th/5th

centuries (e.g. Laing 1975: figure 1). Even the tide of

anti-migrationism as explanation for culture change which swept

through British prehistory in the 1970s and washed into Anglo-Saxon

studies in the 1980s left this concept remarkably intact. Irish

historians still regularly speak of the 'Irish colonies in Britain'

(Ò

Cr òinin

1995: 18; Byrne 1973: 9), and British anti-invasionist prehistorians

seem happy to accept the concept (e.g. Cunliffe 1979:163. figure).

The insistence on an explicitly colonialist terminology is somewhat

ironic given the past reaction of many Irish archaeologists to what

they perceived as intellectual crypto-colonialism of British

archaeologists and art historians over the origin of the Insular Art

illustrated manuscripts and items such as hanging bowls. Exactly

why colonialist explanations should have survived in the 'Celtic

West' while being hotly debated in eastern Britain is of

considerable interest, but not the purpose of this paper, which is

to provide a critical examination of the archaeological, historical

and linguistic evidence for a Scottic migration, and provide a new

explanation for the origins of Dal Riata.

There had

never been any serious archaeological justification for the

supposed Scottic invasion. Leslie Alcock is one of the few to

have looked at the archaeological evident detail, coming to the

conclusion that 'The settlements show very little sign of the

transportation of material culture to Dalriadic Scotland or to

Dyfed' (Alcock 1970: 65). This lack of archaeological evidence has

led some younger archaeologists to adopt a more cautious approach,

suggesting that perhaps there was an elite takeover of the local

ruling dynasty, rather than a mass migration of peoples, and that

contact may have taken place over a longer time-scale than

the conventional view (Foster 1995 13-14). The paradigm of Irish

migration remains strong however, bolstered by the evidence from

other areas of western Britain. During the expansion of interest in

'Dark Age Britain', scholars familiar with the historical and

genealogical accounts of Irish origins of some western kingdoms.

explicitly searched for, and believed they had found, archaeological

evidence for these migrations. Examples can be quoted for ogham

stones in Dyfed. Brecon, Gwynedd and Dumnonia (Macalister 1949);

placenames in Dyfed (Richards 1960). Galloway (Nicolaisen 1976) and

Cornwall (Thomas 1973); settlement forms in Somerset (Rahtz 1976);

and pottery in Cornwall (Thomas 1968). This illustrates that there

was a climate amongst scholars working in this area who saw cultural

explanations terms of an historical/linguistic paradigm which they

applied to all areas of western Britain.

Archaeological evidence

If there

had been any substantial movement of people into Argyll, there

should be some sign of this in the archaeological record, even

though few would now accept a simplistic equation of material

culture and population groups. One reason why no evidence has been

brought forward in the past is the relative lack of archaeological

investigation in Argyll, and also in Antrim. However, since Alcock

produced his 1970 paper there has been substantial progress in

understanding early medieval Argyll, giving us the opportunity to

re-examine the archaeological evidence. The areas of material

culture where we might expect to see signs of incomers from a

different cultural group are in personal jewellery such as brooches

and pins and settlement forms. Both areas were aceramic. at this

period.

The

characteristic settlement forms in Ireland are circular enclosures

with earthen banks (raths) or stone walls (cashels), and artificial

island dwellings (crannogs). Crannogs are found in Argyll, but

unfortunately for proponents of an Irish origin for crannogs,

dendrochronological dating has shown that

Scottish crannogs have been constructed since the early Iron Age

(Barber & Crone 1993), while Irish ones almost all date from

after.AD 600 (Baillie 1985; Lynn 1983), suggesting if anything an

influence from Scotland to Ireland. Although recent work has

sugested some Irish crannogs may be earlier than t5hjs and that some

Scottish crannogs may share constructional features with Irish ones

(Crone 2000), this does no more than suggest a shared cultural

milieu which may have lasted over a very long period and covered

most of Scotland and Ireland.

The raths

and cashels of Ireland are the characteristic early medieval

settlement form, with over 30.000 recorded (Stout 1997). None,

however, are known from Argyll. The characteristic settlement form

in Argyll is the hilltop dun, a sub-circular stone walled roofed

enclosure with features such as internal wall-stairs and intra-mural

chambers (RCAHMS 1988: 31). Radiocarbon dates show that these have

been built since the early iron age through to the late lst

millennium AD, and form a coherent area of distinctive settlement

type in Argyll in contrast to the brochs, enclosures and forts of

other areas of Scotland (Henderson 2000: figure 1). There is

therefore no evidence of a change in the normal settlement type at

any point in the 1st millennium AD and no basis for suggesting any

significant population movement between Antrim and Argyll in the 1st

millennium AD. At best, the evidence shows a shared cultural region

from the Iron Age, with some subsequent divergence in the later 1st

millennium ad. Any

cultural influences could be argued as likely to have been going

from Scotland to Ireland rather than vice versa.

If there was no major

movement of people, perhaps there was an elite takeover, similar to

the Norman invasion of England. The lack of change in domestic

equipment and settlement form could then be explained by the

adoption of local cultural traditions. One might expect, however,

that such an elite would differentiate themselves in some way in

terms of their group identity. At this period there is good evidence

that one way in which this was done was through the use of

distinctive personal jewellery, particularly brooches (Nieke 1993),

and most royal sites of the period have produced evidence of

manufacture of silver and gold brooches (Campbell 1990). The

distributions of different forms of early medieval brooches and pins

show strong regional patterns, and though these may not coincide

with political or ethnic boundaries, they do suggest a relationship

with some form of group identity. Rather strangely, these

distributions do not appear to have been studied in relation to the

migration theory.

The main

form of brooch in 4th-6th century Ireland is the

zoomorphic penannular brooch (Kilbride-Jones 1980). The typological

development and dating of these brooches has been controversial,

but has been recently elucidated by Raghnal

Ó

Floinn (forthcoming). The form developed in the late 4th century in

western Britain in the Severn Valley, but quickly spread to eastern

Ireland where new forms were developed. These brooches are widely

distributed in Ireland, but not one has been found in Argyll. The

situation is similar with dress-pins, as one of the commonest types

with over 40 examples in Ireland, the spiral-ringed ring-headed pin,

was particularly common in the north (Campbell 1999:14. figure), but

only one is known in Argyll. Conversely, the commonest type of

brooch in western British areas was the Type G penannular. Again the

typology and chronology has been much debated, but a general

development from a sub-Roman form (G 1) in

southwest Britain was followed by later types (G2 and G3) in

northwestern areas, A workshop for Type G3 was found at Dunadd in

Dal Riata (Lane & Campbell 2000) and other Type G3

production sites have boon found in Ireland, at Dooey. Donegal and

Movnagh Lough, Meath. Are we here at last seeing evidence of a

distinctive cultural feature moving from Ireland to Argyll?

Unfortunately not. as the Scottish examples date to the early and

mid 7th century, while the Movnagh Lough metalworking phase is

dated by dendrochronology to the early 8th century (Bradley 1993).

Again, any cultural influence would appear to be in the opposite

direction.

Thus

there is no evidence in the archaeological record for any

population movement from Ireland to Scotland, other than travel by

occasional individuals. In Anglo-Saxon England we have an

archaeologically invisible native British population, and debate

centres on the extent to which, they adopted the cultural package

of Anglo-Saxons. In Argyll in contrast, .it is the Goidelic invaders

who are archaeologically invisible.

Historical evidence

The

documentary sources for the migration of the Scotti are of

varying date and validity but, as with the archaeological evidence,

have not received full critical assessment by historians. The

clearest expression is in the Irish chronicles, a source which has

the best potential for containing contemporary records of early

medieval events. In the Annals of Tighernach, an entry for around

AD 500 reads, 'Feargus mor mac earca cum gente dalriada partem

britania tenuit et ibi mortus est' — 'Fergus Mor mac Erc, with

the nation of Dal Riada, took (or held) part of Britain, and died

there'. This clear statement of invasion and colonization is,

however, not a contemporary record, as is shown by the form of the

Irish words. Dalriada, Feargus and Earca are Middle

Irish forms where one would expect the Old Irish Dalriata, Fergus

and Erca. These spellings show that the entry could not

have been written before the 10th century. It has been strongly

argued that this entry, which is the earliest independent record of

Fergus, is one of a series of insertions in the Annals derived from

a 10th-century 'Chronicle of Clonmacnoise' (Dumville 1993:187:

Grabowski & Dumville 1984) and cannot be taken as independent

evidence of colonization.

The other

main source is the Senchus Fer nAlban (History of the Men of

Scotland). This very important document is a social survey and

genealogy of the kings of Dal Riata. believed to have been

originally written in the later 7th century and modified in the 10th

century (Bannerman 1974). Even accepting the supposedly

10th-century version of the text uncritically, it does not refer to

settlement but is a genealogical statement of the origins of the

Scottish kings: 'Erc, moreover had twelve sons .i. six of them

took possession of Alba.' (Bannerman 1974: 47 ), and there

follows a genealogy of the Dalriadan kings from Fergus Mor to the

mid 7th century. It is important to note that nowhere is a mass

movement of peoples mentioned, it is purely an aristocratic, and

specifically royal, takeover of Scotland. However, this account also

cannot be a contemporary record, and can be

shown to be part of the 10th century or later rewriting of the

original text (Bannerman 1974 130-32), as Alba was not used

as a term for Scotland before the 10th century.

The other

early source relating to the origins of Dal Riata is found in

Bede's history of the English church, written in the early 8th

century. Bede's account differs from that of the Senchus. After

describing the wanderings of the Britons and Picts, he says that

Britain received a third tribe,... namely the Irish. They came from

Ireland under their leader Reudai and won lands from the Picts...

they are still called Dalreudini after this leader' (Colgrave’s

Mynors 1969: 18-19). To summarize historical sources, it appears

that there are two conflicting accounts of the Irish origins of

Scottish Dalriada. The first, exemplified by the Senchus and the

Annals of Tigernach entry, belongs to no dates back to at least the

8th century. Bannerman has highlighted the difference between the

traditions, and suggests that an older tradition reported by Bede,

was supplanted in the 10th century by the Fergus Mor story for

political purposes of the time (Bannerman 1974:132)

These

sources, and some other later. material, are clearly origin legends

of a type common to most peoples of the period, constructed to show

the descent of a ruling dynasty from a powerful, mythical or

religious figure. Such genealogies, could be, and often were,

manipulated to suit the political climate of the time as shown by

the replacement of Carpre Riata by Fergus Mor. The genealogies

cannot be taken as indications of past population movement or even

kinship ties. Recent research has lighted how Middle Irish

historians were promulgating a view of Irish kingship which had a

considerable effect on Scottish politics from 10th to the 13th

centuries. Herbert (2000) has shown how the Irish view of kingship,

and political marriages, were influencing Scottish kings in the 10th

centurv towards the concept of kingship of a land (Alba) rather than

a people (the Dal Riata}, and Duffy (2000) has demonstrated

that there was Irish support for one line of rival claimants to the

Scottish throne in the 11th century. This influence continued in the

12th-13th centuries (Broun 1999). It is probable that in this

climate that the manipulation of the genealogies took place, with

each lineage trying to outdo the other

in

stressing their

antiquitv

and Irish origins, The earlier version

of

the legend was possibly constructed to bolster Dal Riata

claims to territory in Antrim.

The critique

of the sources presented above

particularlyis not particularly new — each of the elements

has been noted in the past, if not discussed indetail,

but this has not led historians to question the invasion hypothesis.

For example, in a recent paper David Dumville, an eminent

historian

and himself a noted deconstructer of

early medieval myths, dismisses both the Fergus

and

Bede's account, while in the same

paragraph

accepting the migration of settlers

(Dumville;

1993: 187). The absence of a critical appraisal of the migration

story may be due to

an easy

acceptance by historians of the invasion

paradigm. History has been largely unaffected by the anti-migration

backlash which

affected archaeology, not least because medieval

historians work in a period when there

are many indisputable invasions, although also

due to

a rejection of post-modernist approaches

(e.g.

Evans

1999). As far as Argyll is concerned.

although few historians would now take the

Fergus

Mor story at face value, the linguistic

evidence

seems so clear that there is readiness

to

accept the concept of an Irish invasion or

takeover,

even if the actual details are uncertainand unsupported by the

evidence.

Linguistic evidence

Linguistic

evidence thus seems to provide the securest evidence for invasion by

Gaels, and as we have seen, seems to have influenced historians and

archaeologists to accept the theory even though they themselves have

little evidence to support it. The presence of Gaelic speakers in

early medieval Argyll is undoubted. Adomnan writing in Argyll in the

late 7th century inhabits an entirely Gaelic world: all the

placenames and personal names referred to in Argyll are Gaelic: the

people of Argyll are 'the Scotti in Britain', and he comments that

Columba needed translators when he travelled to Pictish areas

(Sharpe 1995: 32). In addition, the modern placenames of Argyll are

all of Goidelic origin, in contrast to eastern Scotland where

there is a substantial Brittonic substratum, even if many were

adopted by later Gaelic speakers (Nicolaisen 1976; Taylor 1994). Yet

Pictish was replaced by Gaelic as the language of eastern Scotland

only a few hundred years after

Adomnan,

so we would expect to see some Brittonic substratum in the

placenames of Argyll. The traditional explanation is that original

Brittonic speakers were totally displaced by Gaelic speaking

settlers, removing all evidence of Brittonic, settlement and

landscape names. Such a complete obliteration without substantial

population movement, which, as we have seen, is archaeologically

invisible, would be almost unparalleled in onomastic history.

What is

the evidence for this, other than the historical accounts of an

invasion from Ireland? The only evidence for the language spoken in

Argyll before the early medieval period is Ptolemy's Geographv

written in the early 2nd century. This locates the tribe of the

Epidii. and a peninsula called Epidion Akron, on the

west coast of Scotland, in an area generally equated with Kintyre (Rivel

& Smith 1979: 360-fil). Epidii is P-Celtic, and therefore by

implication this area was inhabited by Brittonic speakers. Apart

from the dangers of relying on a single word to support a hypothesis

of an entire language, there are good reasons for questioning this

evidence. Ptolemy's source for his Scottish names was probably from

the Scottish Central Lowlands, and may have transmitted the

Brittonic form of a Goidelic tribal name, or even the external name

given to the tribe by Brittonic speakers. Before the rapid

divergence of Goidelic and Brittonic in the centuries around the

collapse of the Roman Empire there may have been a much less

homogenous pattern of language than we assume for the later periods.

In support of this it is interesting that the P-Celtic tribal name

Menapii appears in Ptolemy's list of tribes in Ireland

itself, and that several peoples of northern Ireland were known as

Cruithi, Goidelic for 'British', but these peoples are

accepted as being Goidelic speakers, and no 'British invasion' of

Ireland is now postulated on the basis of this evidence (Toner

2000: 73). The only reason the name Epidii is used as

evidence for invasion is that it appeared to support the historical

evidence, which we have seen is unreliable. The traditional view

seems inherently unlikely, based as it is on the evidence of a

single word, and a simpler model is proposed below.

While

no-one disputes that a divergence between Goidelic and Brittonic

took place, and that Goidelic retains the most archaic features

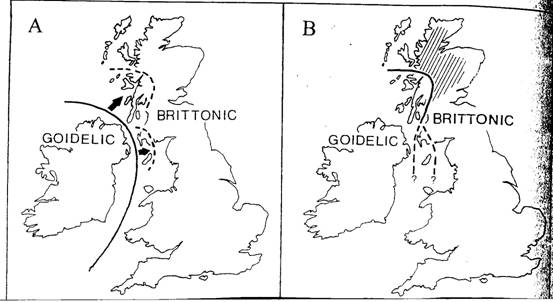

FIGURE 1. Two

differing views of the fault-line between Goidelic and Brittonic. A

Traditional view of the sea as the initial dividing mechanism, with

subsequent spread of Goidelic eastwards. B Alternative with the

Scottish Highlands as the original dividing line between the

languages.

of the Celtic language

group, the question is where the original 'fault-line' between the

two is to be placed. In their interpretation, linguists have tended

to be guided by the historical paradigm in their explanations of

language change in western Britain (FIGURE 1A). More subtly. I

believe they have been affected by a geographical viewpoint which is

based on a modern perception of communications and polities which

sees 'Scotland' and 'Ireland' as independent geographical units.

Thus, the Irish Sea and North Channel have come to be seen as the

dividing line between Gael and Briton, only to be crossed by

invasion. This view was not shared by early medieval commentators,

who saw the dividing line as Druim Albin. the 'Spine of

Britain' (the Grampian Highlands) being the linguistic barrier. It

should not surprise us that the Highlands were a communications

barrier. There are only two or three narrow routeways through the

Highland massif, each involving several days travel on foot. It is

easy to see how linguistic differentiation could take place when the

peoples on either side of this barrier were only in sporadic

communication. On the west coast however, most of Argyll is no more

than a day's sail from Ireland, and at closest the distance between

Argyll and Ireland is only 20 kilometres. There is abundant evidence

to show that early medieval Argyll was a sea-based society

(Bannerman 1974; Campbell 1999). In this context the North Channel

can be seen as a linking mechanism rather than thee dividing one

envisaged in the concept of the 'sea-divided Gael' (O'Rahilly 1932:

123). The islands of Rathlin and Tiree are respectively 20 km and

100 km from mainland Argyll, though Rathlin is today officially in

Ireland. and Tiree in Scotland. Both are clearly part of one

archipelago where good sea communications would enable the same

language to continue to be spoken and develop in tandem. Further

south, the much wider Irish Sea would have made daily communication

more difficult, and the 'fault ine” could have lain between Ireland

and mainland England and Wales (FIGURE IB).

An alternative view

.

To

summarize, if there was a mass migration from Ireland to Scotland,

there should be some sign of this in the archaeological record, but

there is none. If there was only an elite takeover by a warband, who

must have adopted local material culture and settlement forms, there

should

be signs of the language of the native majority in the placenames,

but again there is none. A purely dynastic takeover would not have

led to language change on the scale seen, no clear historical

backing. My reading of the archaeological, historical and linguistic

evidence is radically different from the traditional account, but

much simpler.

I suggest

that the people inhabiting Argyll maintained a regional identity

from at least the Iron Age through to the medieval period and that

throughout this period they were Gaelic speakers. In this maritime

province, sea communications dominated, and allowed a shared archaic

language to be maintained, isolated from linguistic developments

which were taking place in the areas of Britain to the east of the

Highland massif in the Late Roman period,. Occasional developments

in material culture settlement types could pass from one area of the

west to another, and of course individuals moved between the areas,

but this was not on a sufficient scale to produce an homogenous

cultural province. By the early medieval period, the emphasis on

marine transport in Argyll allowed the development of a formidable

navy, capable of maintaining a strong political identity within

Argyll, and allowing Dal Riata to.become an expansionist

force in the area attacking as far away as Orkney, the Isle of Man

and the west coast of Ireland (Campbell 1999: 53; figure). For a

time during this early period. Dal Riata extended its

control to the area of Antrim closest to Argyll, much as the Lords

of jthe Isles were to do in the later medieval period, and thnis

area also became known as Dal Riata. During the Middle Irish

period, when claims of the Irish ancestry of Scottish royalty were

being elaborated, a process of 'reverse engineering' was used by

Irish writers to explain the existence of an Irish Dal Riata

as the progenitor of Scottish Dal Riata rather than vice

In

conclusion, the Irish migration hypothesis seems to be a classic

case of long-held historical beliefs influencing not only the

interpretation of documentary sources themselves, but the

subsequent invasion paradigm being accepted uncritically in the

related disciplines of archaeology and linguistics. The paradigm has

been supported by a series of mutually sustaining positions where

archaeologists have looked to the historical/linguistic model,

historians have been supported bv linguists, and the linguists by

the historians. There are clear parallels here to the situation

recently reviewed by Patrick Sims-Williams (1998) exploring the

relationship of paradigm acceptance between geneticists, linguists

and historians, and Forsyth (1997) in her demonstration of how

linguists were driven by outmoded archaeological thought, in the

question of the origins of the Pictish language. I believe that none

of the evidence is capable of supporting the traditional

explanations, and that closer dialogue between historians, linguists

and archaeologists can lead to a better understanding of the

construction of identity and processes of social change in the early

medieval period. The work of Forsyth (1997) and Taylor (1994) on

Finland, and Smith (forthcoming) on Brittany are signs that this is

already happening. Surelv the question that is of interest here is

not 'where did people come from?', but 'how did people establish and

change their personal and group identity by manipulating oral,

literary and material culture?'. Indeed, merely by re-labelling the

supposed 'Irish settlers' as 'Gaelic speakers', following the

practice of contemporary writers such as Adomnan. the whole issue

can be studied in an atmosphere free from the colonialist

implications which have distorted the study of early medieval

western Britain.

Acknowledgements

The ideas

in this paper have been presented in various seminars over the last

few years and I would like to thank Dauvit Broun,Thomas Clancy,

Steve Driscoll, Katherine Forsyth, Sian Jones, Robert O Maodolach,

Simon Taylor and Alex Woolf for stimulative and helpful discussion,

without implicating them n the ideas put forward here.

References

ALCOCK.

L. 1970. Was there an Irish-Sea Culture-Province in The Dark Ages?,

in D. Moore (ed.), The Irish Sea Prvoince in archaeology and

history: 55-65. Cardiff: Cambrian Archaeological Association.

BAILLIE,M..G.I.. 1985. Irish dendrochronology and radiocarbon

dating. Ulster Journal of Archaeology 4S: 11-23.

BANNERMAN,J. 1974 Studies in the history of Dalriada.

Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press.

BARBER

J.W. &

B.A. crone. Crannogs;

a diminishing resource? A survey of the crannogs of southwest

Scotland and excavations at Buiston Crannog Antiquitv 67:

520-33.

BRADLEY,/. 1993. Moynagh Lough an in Insular workshop of the Second

Qiarter of the 8th century. in Spearmnan & Higgit

(ed.): 74-81.

BROUN, D.

1999. The Irish Identity of the kingdom of the Scots.

Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

BYRNE,!F.J. 1973. Irish Kings and High-kings. London:

Batsford.

CAMPBELL,

E. 1996. Trade in the Dark Age West: a peripheral activity?, in B.

Crawford (ed.), Scotland in Dark Age Britain: 79-91.

Aberdeen: Scottish Cultural Press.

1999.

Saints and Sea-kings: the jfirst kingdom of the Scots Edinburgh:

Cannongate/Historic Scotland.

COLGRAVE,B..

& R.A.B. mynors (ed).

1969. Bede's Ecclesiastical history of the English People.

Oxford: Clarendon Press.

crone,

A.

2000. The history of a Scottish Lowland crannog: Excavations at

Buiston, Ayrshire. 1989—90. Edinburgh: STAR.

CUNLlFFE.

B. 1979. The Celtic World. New York (NY): McGraw Hill.

DlUFFY.,S. 2000. Ireland and Scotland, 1014-1169: contacts and

caveats, in A. Smyth (ed.) Seanchas: Studies in early medieval

Irish archaeology, history and literature in honour ot Francis J.

Byrne,. 348—56. Dublin: Four Courts Press.

DUMVILLE,

D. 1993. Saint Patrick and the Christianisation of Dal Riata.

in D. Dumville (ed.). Saint Patrick.

ad 495-1993: 183-9.

Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

EVANS,

K.J. 1999. In defence of history. London: Granta.

FERGUSON,

W. 1998. The identity of the Scottish nation: an historic quest.

Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

FORSYTH,

K. 1997. Language in Pictland: the case against non-Indo-European

Pictish. Utrecht: die Keltische Drank.' Miinster: Nodus

Publikationen.

FOSTER.

S. 1995. Picts. Gaels and Scots. Edinburgh: Historic

Scotland.

GRABOWSKI. K. & D. DUMVlLLE. 1984. Annals of medieval Ireland

and Wales: The Clonmacnoise-group texts:. Woodbridge: Boydell

Press.

HENDERSON,

I. 2000.

Shared traditions? The drystone settlement records of Atlantic

Scotland and Ireland 700 BC— AD 200. in IJ. Henderson (ed.). The

prehistory and early history of Atlantic Europe: 117-54. Oxford:

British Archaeological Reports. International series 861.

HERBERT.

M. 2000. Ri Eirenn, Hi Alban: kingship and identity in the

ninth and tenth centuries, in S. Taylor (ed.). Kings, clerics and

chronicles in Scotland 500-1297: 62-72. Dublin: Four Courts.

KILBRIDE-JONE.S. H.E. 1980. Zoomorphic pennanular brooches.

London: Thames & Hudson.

LAING.

L. 197S.

The archaeology of late Celtic Britain and Ireland 400-1200 AD.

London: Methuen.

LANE,

. A. & E. CAMPBELL.

2000. Excavations at Dunadd: an early Dalriadic capital.

Oxford: Oxbow.

LYNN, C

1983 Some early ring-forts and crannogs. Journal Irish Archaeology

1: 47—62

NICOLAISEN

W.F.H.

1976. Scottish place-names. London Batsford.

NIEKE, M.

1993. Pennanular and related brooches : secular

nament or symbol in action?, in Spearman & Higgit135-42.

O’

CROlNIN, D. 1995, Early medieval Ireland 400-1200

London:

Longmans.

O’

FLOINN. R. Forthcoming. Artefacts in context: personal nament in

early medieval Britain and Ireland,

Proceedings

of the Fourth International. Conference on Insular Art.

Cardiff.

O'

RAHILLY, T.F. 1932. Irish dialects past and present with chapters

on Scottish and Manx. Dublin: Brown & Nolan

RAHTZ,

P.A.

1976. Irish settlements in Somerset, Proceedings of the Royal

Irish Academy 76C: 223-30.

RCAHMS.

1988. Argvll: an inventory of the ancient

6:

Mid-Argyll. Edinburgh: HMSO.

RICHARDS.

M. I960. Irish Settlement? in southwest Wales; a topographical

approach, Journl: ot the Roval Society of

Antiquaries

of The place-names of Roman Britain.

London:

Batsford.

SHARPE,

R. (ed. & trans.). 1995. Adomnan of lona. Life of Columba

London:

Penguin.

SIMS-WILLIAMS. P. 199B. Genetics, linguistics, and prehistory;

thinking big and thinking straight:. Antiquitv72 505-27

SMITH,J..

Forthcoming. Confronting identities: the rhetorical reality of a

Carolingian frontier, in W. Pohld & M. Diesenberger (eds).

Integration und Herrschaft. Ethnische Identitaten und kulturelle

Muster im fruhen Mittelalter Vienna.

SPEARMAN.

R.M. & J.

HlGGlTT( ed.). 1993. The age of Migrating ideas. Earlv Medieval

art in Northern Britain and Ireland

Edinburgh: National Museums of Scotland/Stroud Alan Sutton.

STOUT,

M. 1997.

The Irish ring-fort. Dublin: Four Courts Press

TAYLOR,

S. 1994. Some early Scottish place-names and Queen Margaret.

Scottish Language 13: 1—17

(Ed.).

2000. Kings, clerics and chronicles in Scotland 505-1297.

Dublin: Four Courts Press.

THOMAS

C. 1968.

Grass-marked pottery in Cornwall in ? Coles & D.D.A. Simpson (ed.).

Studies in Ancient Europe311—32. Leicester: Leicester

University Press.

1973.

Irish colonists in South West Britain, World Archaeologv 5:

5—13. TONER. G. 2000.

identifying Ptolemv ‘s Irish places and tribes in D.N. Parsons & P.

Sims-Williams (ed.), Ptolemy; towards

a linguistic atlas of the earliest Celtic place-names of Europe:

73-82.

Aberstwvth Centre for Medieval Celtic Studies.

A critical

analysis of Dr Ewan Campbell's paper "Were the Scots Irish?"

By Bridget Brennan (pdf) |