|

With the Road-engineer -

Anne Grant of Laggan - The Man at the Churchyard Gate - I Visit the

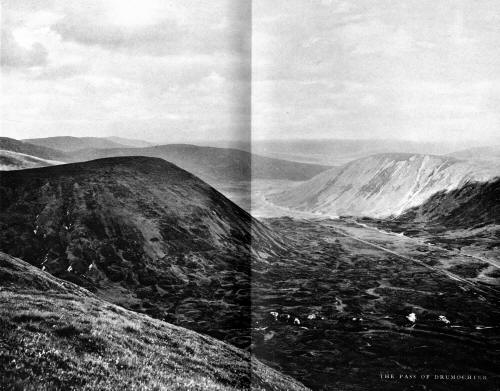

Minister and Leave for Dalwhinnie - The Pass of Drumochter - The Solitary

Woman - On to Blair Atholl.

WHY an engineer should have

been more good-natured about his personal belongings than, say, an

architect or a chartered accountant, I did not understand, but I took the

word of my hostess for it. To my satisfaction, I found that the spare

shirt and flannel trousers in my pack were dry; and stripping off my wet

clothes, which were to hang for the night before the kitchen fire, I

shuffled downstairs to the sitting-room in the engineer's dressing-gown

and slippers.

He was a young man with a

lean pleasant face, and he was filling a huge briar pipe from a tin of

"Country Life " tobacco. When I began to thank him for the use of his

things, and to apologise for thus breaking in upon his privacy, he laughed

and pushed an armchair towards the fire for me. "So you've been over the

Corrieyairack?" he said.

Presently, I learned that

my companion was a road-engineer, and his name was Melville.

"You were on Wade's road

all the way," he explained, "except that new bit from the Catholic chapel

at the Dun. I'm on a rather interesting job here, - for I'm re-making

Wade's roads, and some of them haven't been touched-except for the

potholes-since the old boy made them two hundred years ago . . . Are you

interested in General Wade?"

If the gods had been unkind

to me during the day, they could not have made more generous reparation in

the evening. I had been led, as it were, blindfold to a man who knew every

contour of that countryside -and who was eager to talk about General Wade!

There was no place in all Badenoch where I would rather have spent the

night.

"Wade knew his job," said

Melville, lighting his big pipe. "Whenever he could, he laid his roads so

that an army couldn't be ambushed on them. He would often build a road a

little way up the hillside when it would have been easier to put it right

down in the valley. A shrewd old chap. When he came to a marsh he didn't

try to dig foundations-that would have been a hopeless job-he floated his

road on hundreds of bundles of wood-faggots. Come to think of it,"

Melville continued, "that's just about what we're doing to-day. We float

the roads over marshy ground on rafts of concrete. History repeating

itself! I don't say Wade was as great an engineer as Thomas Telford - the

Caledonian Canal man. Telford knew a lot more about bridges than Wade, but

he was a great old fellow all the same." And then he laughed. "Queer to

think that General Wade built these roads so that the Government could

keep a closer eye on the clans - and it was these very roads that helped

Prince Charlie to get to Edinburgh before Johnnie Cope !"

Melville was interested to

know that I was walking in the footsteps of the Prince, and was determined

to cover all the country through which he passed both in Scotland and

England and as a fugitive in the Isles. My present destination was

Edinburgh, I told him, and later I would go to Derby, then turn and walk

north to Culloden, and finally follow his tracks through the heather.

The idea fired Melville to

sudden enthusiasm. "You know the song called 'The Road to the Isles'?" he

said, and began to hum it: "` By Tummel and by Rannoch and Lochaber I will

go, by heather tracks I'll foot it in the wild . . .' Well, last year I

did that walk to the Isles-but it's the Prince Charlie road for me next

time! I dare say the Corrieyairack's the worst bit . . ."

We were interrupted by

supper, and afterwards we talked until the hour of one chimed on the

mantelpiece clock-a clock which, an inscription told me, had been a prize

at a sheepdog trial - and I went upstairs to my bedroom, where huge

sheep-skin rugs lay upon' the floor ; and I fell at once into a sound

sleep.

I was awakened next morning

by the sun glittering on the window at my bedside. Whether the rain had

gone for good, I could not tell, and after breakfast both Melville and the

farmer thought there was more of it yet to come. I was tempted to stop in

Laggan for a day or two, but a full week had passed since I had left

Moidart, and I had still more than a hundred and fifty miles to cover

before I reached Edinburgh, so I decided to push on that morning. Melville

said he was going to Laggan Bridge, three quarters of a mile away, and he

offered me a lift on the back of his motor-cycle, which I accepted ; and

while I straddled his pillion seat, like a witch on a broomstick, he took

me at a terrific pace across that wide green hollow among the mountains

that has given the place its name. Clumps of trees were on the hillsides

around us, and to the west I could see the conical hill called the Dun,

clothed to the summit with firs and pines. A few cottages were scattered

about, but there were more ruins than habitations, and it was a little

saddening to think that a hundred years ago the population of this parish

was over twelve hundred. Leaning his motor-cycle against a dyke, Melville

went to attend to some business in a cottage where he had a temporary

office, and I strolled into the kirkyard.

This church was a more

recent building than the one which the Rev. James Grant built towards the

end of the eighteenth century, and to-day the Rev. James is remembered

only as the husband of the famous Anne Grant of Laggan. On the previous

forenoon, as I had climbed up the north slope of the Corrieyairack, I had

looked into the green glen where their courtship had taken place. What an

extraordinary life that woman had. She had been brought up beside the

lonely Hudson River in America, where her father settled before returning

to Scotland broken in health to become Barrack-master at Fort Augustus. In

New England she had learned to speak Dutch, and in Laggan she acquired

Gaelic so that she could talk to her husband's parishioners. The manse was

a place of hospitality, the stipend was small, and when her husband died

she found herself without a penny and eight children to look after. She

took a farm, but this failed, and soon she was worse off than before. In

1803 she published her first literary work, a volume of poems, which

provided food and shelter for a time, and in 1806 her friends persuaded

her to publish three volumes of the letters she had written from the

Laggan manse. These Letters from the Mountains brought her both money and

fame, and can be read with even greater interest to-day than at the time

when they were written. One of the wisest of the many wise remarks you may

read in these delightful pages is that the Highlanders resemble the French

in being poor with a better grace than other people.

Later, she published a

volume of essays on the superstitions of the Highlands, and there she told

a grim story of a Laggan glen that was haunted. A chieftain discovered

that his daughter was in love with one of the cottagers, and in his wrath

he seized the man and bound him naked on an ant's nest. The lover died in

agony and the girl went mad. She roamed up and down the glen until her

death, and her phantom remained to haunt the place. The Laggan people, in

terror of the Red Woman, refused to go near the sinister glen until Mrs.

Grant's husband laid the ghost by holding a religious service at the place

where it had been so often seen.

Towards the end of Mrs.

Grant's life, Sir Walter Scott had to soothe her feelings, which were hurt

by the smallness of the civil pension allowed her by George IV. In his

Journal, Scott calls her "proud as a Highland woman, vain as a poetess,

and absurd as a bluestocking." But he added: "Catching a pension in these

times is like hunting a pig with a soaped tail. Monstrous apt to slip

through your fingers." Much sorrow came to her; all her children died

except her youngest son; an accident crippled her, so that $he was

confined to the house for the last twenty years of her life. But she had

many friends; her talk was brilliant; and in the end, several legacies

dropped into her lap, making her a comparatively wealthy woman. To-day she

would be called a reactionary and a romantic, and she even hated the idea

of roads being built through the Highlands. These roads, she said, would

afford access to strangers who despise the Highlander ; and luxuries would

be brought into the glens that the people could not afford to pay for, and

would be happier without. She knew how little her Red Indian friends by

the Hudson River in America had gained by being civilised; and she had the

same fears for the Highlander. She foresaw that the ancient culture of the

Gael would be destroyed instead of being allowed to grow and sweeten under

the influence of an appropriate education; and the many Scottish

institutions that are to-day trying to pick up the lost threads, and

reanimate the old culture, show how wise were the words of Anne Grant.

There is little of the fine

old tradition in Laggan to-day. At least, so I gathered from a stranger

with whom I fell into talk at the kirkyard gate. He lived at Kingussie or

Newtonmore - I forget which-and he seemed to know the district well.

"There's still a lot of bitter Calvinism in the Highlands," he said, when

our talk turned to the old and better days. "When the Gael becomes `unco

guid,' he isn't a very pleasant specimen. You see, he's instinctively an

artist, he lives emotionally, the old songs and stories are in his blood.

But repress him, deprive him of his emotional life, and he's a dry stick,

suspicious and self-righteous. I'm not a Catholic myself," he went on,

"but Calvinism in the Highlands did a lot of harm to the spirit of the

Highlander."

I wondered who the stranger

was. His voice suggested that he was a Gaelic speaker; he talked with a

quiet intensity; and I liked his thoughtful eyes. "If you're interested in

the Highlands," he said presently, "there's a man living up there who can

tell you more about them than anybody I know. He's one of the finest men

in Scotland-the minister of Laggan." And he mentioned a name that is known

and reverenced in every corner of the country. " I'm going up to the

minister now," added the stranger. "Come and meet him."

I gladly accepted, and

leaving my pack in Melville's little office, with word that I would be

back in about twenty minutes, I went up the drive with the stranger to the

manse of Laggan.

The minister greeted us at

the front door. He was an unforgettable figure of a man, with a lock of

iron-grey hair across his forehead, the deep eyes of a poet, and a

resonant musical voice. He took us in to a pleasant sitting-room, where a

bagpipe with a Ross tartan lay on the piano. He smiled when my eye kept

straying to it, and we began to talk about bagpipe music. I remarked upon

how vile it used to sound in the officers' mess on guest nights, and the

minister nodded.

"Of course it would," he

agreed. "It's an openair instrument. The Clarsach - the harp-and the

fiddle can be played in the house, but the bagpipe needs God's out of

doors. At least it does for the Caol Mor - that's the Pibroch, the

classical music of the bagpipe. It's being revived, I'm thankful to say,

the Caol Mor. Music and song and the love of all beauty-this is the

heritage of the Gael. But many insidious forces have helped to cut us off

from that heritage. For example, the Disarming Act after the 'Forty-five;

it was a wonder that the classical music of the bagpipe survived, but it

did."

I spoke about the age of

the bagpipe, how Dr. MacBain the Celtic scholar declared that it appeared

first in the Lowlands of Scotland, and was not introduced to the Highlands

until the sixteenth century.

"I know," nodded the

minister, "MacBain believed that the bagpipe wasn't of Gaelic origin at

all, and he's a difficult man to contradict. But this much is certain. It

was the Scottish Highlanders, and particularly the Macrimmons of Skye, who

made the bagpipe what it is to-day. Possibly the big drone was added in

their time. But, ah, so much of the lovely Macrimmon music has been

forgotten. They were the masters of the Pibroch."

I begged him to dispel a

little of my ignorance about the Pibroch, and I learned that there are

four kinds, the Lament, the Salute, the Battle-piece, and the Pastoral

Meditation. "The Pibroch had been perfected centuries before it had ever

been written down on paper," said the minister. "The master taught his

pupil

orally. There was a special notation, a sequence of letters that formed

words, and by learning these words the pupil got the actual form of each

Pibroch into his head. That was the method of the Macrimmons."

The minister went on to

tell me about this great family. "Seven hundred years ago they owned land

in the island of Harris. They were conquered by Paul Balkison, and he is

said to have bequeathed his territory to the ancestor of the MacLeods, so

the MacLeods became the overlords of the Macrimmons. It was the eighth

MacLeod chief, Alasdair Crotach, who endowed the college of pipe music at

Boreraig, a few miles from the castle of Dunvegan. That was four hundred

and fifty years ago, and the college continued until after the

'Forty-five. No music except Caol Mor was allowed to be played at the

college of the Macrimmons; they prohibited small music like marches,

strathspeys, reels, and the melodies of songs.

"When a piper was composing

a Pibroch," went on the minister, "he fasted for two days beforehand, and

would neither eat nor sleep until the tune was completed. This custom

probably dates back to the time of the Druids. You'll find the Pibroch

only in the West. I know of but one Pibroch that belongs to the eastern

Highlands . . . Of course there were other schools of pipers, such as that

of the Mackays, the MacArthurs, and the Rankines, but they were only

offshoots from the Macrimmon college. You know the old story of Patrick

Mor Macrimmon and Charles II -how a group of pipers were brought into the

presence of His Majesty, and the king asked why one of them had not

uncovered his head. A courtier replied that this was Macrimmon, the king

of pipers. 'Bring forward the king of pipers,' said Charles, with a laugh,

extending his hand to be kissed, and in honour of the great occasion

Patrick composed that loud bombastic piece, ` I have Kissed the King's

Hand.' But it shows that the Macrimmons did regard themselves as

extraordinary men, which of course they were ...

"I've often told the story

of the blind piper Ian Dall Mackay," the minister continued. "He was a

pupil of the Macrimmons, and had heard how other musicians had interpreted

in their music the beauty of the sunset. Well, the greatest ambition of

Ian's life was to compose a Pibroch describing the colours of the rainbow.

One fine summer evening he was told there was a rainbow in the sky, and he

raised his face in reverence to the beauty his blind eyes could not see.

When a lark started singing he cried in sudden exaltation, `That's the

tune of the rainbow !' The same evening he composed his Pibroch . . . It's

obvious that in many of their battle-pieces the Macrimmons went to nature

for their themes-you can hear the voice of thunder in their music, and the

sound of a mountain torrent, the cry of an eagle, and sometimes the roar

of the Atlantic breakers on the rocks at Skye . . ."

Of the four kinds of

Pibroch which the minister had described, I wondered which could be

regarded as the finest.

"The Lament," he said

quietly. "In the Lament, the spirit of the Gael touches the highest point

of beauty. It springs from the deep sadness in his heart. As a Pibroch,

'The Lament for the Children' stands alone . . . No, I would rather not

play it now-look at the sunshine out of doors. It needs the hour of

twilight and the appropriate mood for that great sad music."

It was nearly eleven

o'clock before I left Laggan Bridge, and I hoped to reach Blair Atholl by

nightfall. This was optimistic I knew; but since I was now heading for the

south on the main road down through the Central Highlands, I had little

fear of being stranded for the night. There was bound to be traffic on

that road, I concluded, and at the worst I would probably be able to beg a

lift for the last few miles into Blair Atholl.

On the back of his motor-cycle, my civil engineer swept me up over the

hill by Catlodge (which used to be called Cattleack), and past the little

lonely grey schoolhouse near the summit. On the fence at the roadside I

saw that bunches of heather had been tied to prevent grouse from killing

themselves against the wire in flight, and we came down to a few scattered

cottages in the middle of a flat plain. I watched Melville on his machine

until he was out of sight, and then turned my face to the south country.

I knew nothing about the

land that was now before me; and the road that joins Perth with the North

had all the freshness of a new countryside. But the very fact that I was

on a main road depressed me; I was illogical enough to resent the

thousands of other eyes that had stared at those hillsides since the month

of June; and as I strode forward, I thought of the fairy-haunted land of

the West I had left behind me a week before.

But a surprise awaited me.

Far from finding myself in a countryside littered with ugly little

teashops, I found myself tramping into the mouth of a strath as desolate

as that great hollow glen between Glenfinnan and Loch Eil. At Dalwhinnie,

which lies in a saucer among the hills, the Prince halted for the night on

Thursday 29th August 1745. Tradition has it that he slept beside his men

in the heather, although near at hand there was the inn that Sir John Cope

had occupied three nights before. Why did he not sleep at the inn ? No

doubt he preferred the heather to a bed that Cope had occupied. This inn

had been built by General Wade, and- the old building now forms part of

the present hotel near the road. But before the Prince reached Dalwhinnie

that Thursday night, a prisoner was brought to him, a man of importance in

the Highlands, and his name was Evan Macpherson of Cluny.

He held a Captain's

commission in Lord Loudoun's regiment, which was part of Cope's army. His

wife, a daughter of Lord Lovat, was at heart a Jacobite, but she did all

she could to prevent Cluny from joining the Prince. She said that his oath

to King George could not be broken without dishonour, and Cluny had

reported himself to Sir John Cope at Dalwhinnie on the Monday night, when

he had received a surly order to gather his clan and be ready to march on

the following day, but Cluny had done nothing except nurse his resentment

at being treated like a junior subaltern. His home was only a few miles

away ; and when Cope's army marched past Cluny Castle in the morning the

Chief had been ordered to follow, but Cope had gone on to Inverness

without him.

The Prince got an inkling

of what had happened, sent off a hundred Camerons from Garvamore to take

Cluny prisoner. One is tempted to conjecture that there was a twinkle in

Cluny's eye that evening. Writing about him afterwards to the Secretary of

State, Duncan Forbes of Culloden said: "He was seiz'd by the Rebels that

Night in his house, whether with or without his consent did not then

appear, nor does it now." But the fact remains that, after having been

kept a prisoner for about a week, Cluny returned' to Badenoch and raised

three hundred of his clan for the Prince, and there was no more loyal

officer in the Highland army-and for his loyalty few men paid more dearly.

At noon the next day, when

the Prince was about to continue his march to the South, a company of

Camerons arrived with long faces. On the day before, they had left the

main body to capture the Ruthven Redoubt under the impression that it

contained a great store of meal. The only garrison that Cope had left

behind to defend the place was a corporal and twelve men under Sergeant

Terence Mulloy; but as Dr. Archibald Cameron soon discovered, Mulloy was a

bonny fighter. The Doctor sent him a message advising him to throw up the

sponge, but Mulloy made answer that he was "too old a soldier to surrender

a garrison without first seeing some bloody noses." In Mulloy's own words,

"the Grandee went off with a vast deal of threats." The Camerons attacked

at night, but were compelled to draw off with one man dead and a few

others wounded. When the Prince heard of the outcome of the affair he was

more distressed at the loss of the dead Cameron than at the failure to

capture the Redoubt, for he had disapproved of the attempt from the start.

Indeed, the one man who stands out strongly in the affair of the Ruthven

Redoubt is Sergeant Mulloy himself, and when Cope heard of his dogged

resistance he recommended him for a commission, which was granted. Shortly

after noon on Friday, the Highland army marched south.

I bought some food at a

tiny shop; soon the pagodalike tower on the top of the big distillery was

out of sight ; and passing the end of Loch Ericht, one of the highest

lochs in Scotland, I found myself in a great strath with two mountains on

my right called the Boar of Badenoch and the Atholl Sow. Their slopes were

scarred by gullies in which the morning sun cast black shadows; and beyond

them I saw Loch Garry (not to be confused with the Garry north of the

Caledonian Canal), with its river racing southward beside the

railway-line. Wade's stone stands in that lonely pass. The rough piece of

rock, eight feet high, was erected by the General in 1729 when he finished

the road. He was an unusually tall man, and they say that when the stone

was set up he placed a guinea upon it, to return a year later and find his

coin still there. If this yarn about Wade's guinea is true, then the Pass

of Drumochter in the eighteenth century was as desolate as it is to-day,

for if any boy had lived within a league of this stone, could he have

refrained from climbing to the top of it? As I tramped onward, I noticed

that the modern highway here and there takes a short cut, leaving the old

military road to wind its solitary way among rocks and heather, soon to be

overgrown and to disappear from the eyes of man.

I had expected to meet a

lot of traffic, but I was surprised at how little there was. One or two

private motor-cars raced north, and there was a long spell when I saw not

a living creature except some goats grazing near the road, and a woman

pushing a baby in a perambulator. She was young and well-dressed, and I

felt an almost irresistible impulse to stop her arid ask where in the

world she had come from and where she was going to. She looked as if she

had stepped straight from among the nursemaids in Princes Street Gardens,

yet there she was, with a sleeping infant, miles from any village or any

living thing except the goats. At a burn a little distance from

Dalnacardoch I halted for ten minutes to eat the food I had bought. The

hard smooth road made walking unpleasant, and the blazing sun added to my

discomfort; I thought of the mist and rain on the Corrieyairack the day

before, and the storm through which I had trudged by the river Spey ; and

by the time I reached Dalnacardoch, I would have welcomed a thunder-cloud

with a shout of joy.

But my depression, I think,

was more than physical. That pass, which lies between Badenoch and the

Forest of Atholl, is a savage place. Even in bright sunlight, there is

something inimical about it. You feel that nothing could grow on those

barren mountainsides; you feel that no human being could live there long

without becoming hostile to his fellow men. The place does not strike the

mind with awe like some of the majestic parts of the Highlands-like Glen

Lyon, for example-and it does not stir the fancy like the land in the West

through which I had travelled the week before. This central pass through

the Grampians was once the home of robbers and outlaws, and they could not

have found a more suitable lurking-place. It was late in the afternoon by

the time I reached Calvine, where I drank some tea, and was told that the

Falls of Bruar were half a mile away - the Bruar that Burns visited, and

then wrote to the Duke of Atholl begging him to plant the sides of the

stream with trees. The petition was in verse, and ended with the toast to

"Atholl's honest men, and Atholl's bonny lassies" which Burns had proposed

at the Duke's table during his visit to Blair Atholl - the two happiest

days of his life. Twenty-five years later William Wordsworth and his

sister Dorothy came to see the Bruar Water, and in her journal Dorothy

described how the Duke had granted the poet's petition and had planted the

glen with firs and larches - "children of poor Burns's song." If the

stranger at Calvine who reminded me about Burns's poem had told me about

Dorothy Wordsworth's visit, I might have been tempted to go to the Falls

of Bruar for her sake, as she had gone for the sake of Rab; and after

drinking my tea within sight of Struan - once the home of the chiefs of

Clan Donnachie - I set out for Blair Atholl, four miles distant.

The hills on either hand

were now low and smooth and green. The hand of man was apparent

everywhere-or rather the hand of the landscape-gardener. The sun was low

on my right, and I fancied I could see a smug smile on the face of the

countryside. I remembered how my first glimpse of the green slopes around

Loch Moidart had reminded me of Surrey, and I realised how absurd that

comparison had been. Loch Moidart could no more be compared with Surrey

than Surrey could be likened to the parade-ground of Edinburgh Castle. But

here at Blair Atholl was a bit of Surrey, suave and fat and

self-satisfied, ripe for redroofed bungalows and the pseudo-Elizabethan

horrors of retired City men. I felt that I was coming to the fringes of

some new garden-city, a trim and finicking place where people wore no hats

and lived the artificially simple life in rows of little villas . . . So

my thoughts ran until I pulled myself up. There was nothing wrong with

this place, I said: I was dogtired - so tired indeed that everything

seemed detestable except a clean bed and the promise of twelve hours of

uninterrupted sleep.. A lorry came trundling along behind me, and I acted

on a sudden impulse and put up my hand to the driver. "Ay, hop in, sonny,"

he said, removing the stub of the cigarette that was glued to his lower

lip, and lighting another. He glanced at the pack on my back, "A hicker ?

Ye're fond! " He laughed. "Chaps me no' for the hickin' - I'd rather hae

ma lorry."

"There's a lot to be said

for a lorry," I agreed fervently, loosening the laces of my shoes and

lying back on the jolting seat. A lift in Jove's chariot could not have

been more welcome. We rattled forward on a long straight road under a

canopy of trees, and around the shelter of a hill I saw the peaked top of

Ben Vrackie. Below us, the river Garry crept southward over its bed of

pebbles. Not a soul did we meet on that road, not a motor-car. "Aweel,"

said the driver, drawing up, "here's Blair Atholl for ye. Ay, ye'll get a

bed here." He waved his hand, the lorry rumbled on its way, and I found

myself in the shadow of a gorgeous hedge of purple-leafed plum that

surmounted the top of a high stone wall, with the village ahead of me. |