|

AMONG the famous

prisoners that were incarcerated in the dungeons of the Castle was James

Mhor Macgregor of Bohaldie, the eldest son of Rob Roy, the famous chief

of the Macgregors. James had lost his estate for having held a major’s

commission under the Old Pretender. Robin Oig Macgregor, his younger

brother, having conceived the idea that he would make his fortune by

carrying off an heiress—no uncommon thing in the Highlands —procured

James’s assistance, with a band of Macgregors, armed with target,

pistol, and claymore, who came suddenly from the wilds of Arroquhar.

Surrounding the house of Edinbellie, in Stirlingshire, the abode of a

wealthy widow of only nineteen, they seized her, and, muffling her in a

plaid, bore her to the heather-clad hills where Rowardennan looks down

upon the Gareloch and Glenfruin. There she was married to Robin, who

kept her for three months in defiance of several parties of troops sent

to recover her.

From his general

character James Mhor was considered to be a chief instigator of this

outrage \ thus the vengeance of the Crown was directed against him

rather than Robin, who received some leniency on account of his youth.

He was arrested, tried, and found guilty by the Lords of Justiciary, but

in consequence of some doubt, or because of some informality, sentence

of death was delayed until November 1752. As it was believed that an

attempt to rescue him might be made by the Highlanders serving in the

city as caddies, chairmen, and city guards—for Macgregor’s bravery at

Prestonpans, seven years before, had made him popular with the

clansmen—he was removed by a warrant rom the Lord Justice Clerk,

addressed to General Churchill, from the Tolbooth to the Castle, there

to be kept in close confinement till his fatal day arrived. But it came

to pass that on November 16 one of his daughters, a tall and very

handsome girl, disguised herself as a lame old cobbler and obtained

admittance to the prisoner, bearing a pair of newly soled shoes. The

guards in the adjacent corridors heard James Macgregor scolding the

supposed cobbler with considerable asperity for some time for the

indifferent manner in which his work had been executed. Meanwhile they

were exchanging costumes, and at length James came limping forth

grumbling and swearing. An old and tattered greatcoat enveloped him; he

had donned a leather apron, a pair of old shoes, and ribbed stockings. A

red nightcap was drawn to his ears, and a broad hat slouched over his

eyes. He quitted the Castle undetected, and succeeded in leaving the

city. His flight was soon discovered . The city gates were shut, the

fortress searched, and every man who had been on duty was made prisoner.

A court-martial, consisting of thirteen officers, sat for five days in

the old barracks, and its proceedings ended in two officers being

cashiered, the serjeant who kept the key of Macgregor’s room being

reduced to the ranks, and the flogging of a warder. Macgregor escaped to

France, where he died about the time of the French Revolution in extreme

old age. Robin Oig Macgregor was, however, executed in the Grassmarket

in 1754 for the abduction.

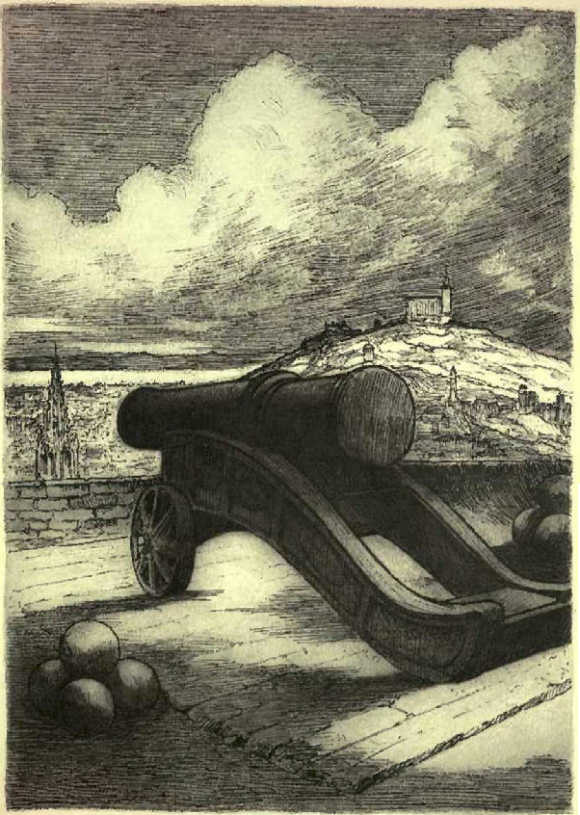

On the Bomb Battery, or

King’s Bastion, directly in front of St. Margaret’s Chapel, stands the

giant piece of ordnance known as Mons Meg, a relic of the fifteenth

century, with its great muzzle commanding the fine panorama of the New

Town. In one respect it is similar in construction to some of our modern

weapons \ that is, the metal is welded together in strong coils. It

measures thirteen feet in length and twenty inches in diameter within

the bore, and weighs upward of five tons. It is supposed to be the most

ancient piece of cannon in Europe with the exception of one at Lisbon.

Grant says that not a vestige of proof can be shown for the popular

belief that this gun was forged at Mons; indeed, unvarying tradition,

supported by very strong corroborative evidence, asserts that it was

formed by Scottish artisans, by order of James II, when he besieged the

rebellious Douglases in the castle of Thrieve, in Galloway, in 1455. He

posted his artillery at the Three Thorns of the Carlinwark,1 which still

survives, but the fire proved ineffective, so a smith named M’Kim and

his sons offered to construct a more efficient piece of ordnance. Toward

this the inhabitants of the vicinity contributed each a gaud, or iron

bar. Tradition, Grant goes on to say, never varied, and indicated a

mound near the Three Thorns as the place of the forging. When the road

was made at that spot this mound was discovered to be a mass of cinders

and the iron debris of a great forge. Another story has it that the King

granted to 'Brawny Kim,’ the smith in question, the lands of Mollance—the

contraction of Mollance to ‘Monce’ and his wife’s name c Meg’ suggests

the origin of the name 'Mons Meg.’

To this day the place

where Mons Meg was mounted is called Knock-cannon. Only two of the great

cannonballs were fired from it before the surrender of Thrieve, and both

have been found. The first, according to the New Statistical Account,

was toward the end of the seventeenth century picked out of the castle

well and delivered to Gordon of Greenlaw. In 1841 the tenant of Thrieve

discovered the second when removing a rubbish heap. The balls piled on

either side of the gun in the Castle are believed to be exactly similar

to those found at Thrieve, and are cut out of Galloway granite from a

quarry on Binnan Hill, near the Carlin-wark. The gun has had several

variations in its name. It has been termed ‘ Mounts Meg,’ 'Munch Meg,’

and ‘the great iron murderer, Muckle Meg.’ Near the breech may be seen a

large rent, which was made in 1632, when a salute was being fired in

honour of the Duke of York, afterwards J imes VII. In 1489 it was

employed at the siege of Dumbarton, and at some time when James IV

invaded England it is supposed he took the gigantic weapon with him on a

new stock made at St. Leonard’s Craig and the accounts at the time

mention the amounts paid to those who brought “ hame Monse and the other

artailzerie frae Dalkeith.” Many are the stories of her achievements. A

shot from her, fired from the castle of Dunnottar a mile and a half

distant, is said to have dismasted an English vessel as she was about to

enter the harbour of Stonehaven, but as Mons Meg was never at Dunnottar

this story cannot be true. During the Civil War in 1571 one of her

bullets fell by mistake through the roof of a house in Edinburgh, for

which the tenant had compensation } and whilst the gun was being dragged

from Blackfriars Yard to the Castle two men died of their exertions.

An extract from the

chamberlain’s roll is both amusing and interesting: “To certain pynours

for their labour in the mounting of Mons out of her lair to be shot, and

for finding and carrying of her bullets after she was shot, from Wardie

Muir, to the Castle, 10d.; to the minstrels who played before Mons down

the street [on occasion of her visit to Holy rood], 14s. for 8 ells of

cloth to cover Mons, 9s. 4d.”

In 1758 the gun was

removed by mistake among a number of unserviceable pieces to the Tower

of London, where it was shown till 1829. When George IV visited

Edinburgh in 1822 Sir Walter Scott pointed out to him the spot of Meg’s

former location on the King’s Bastion of the old fortress, and with all

his powerful eloquence pleaded that she might be restored to her

position again. The King gave his word that it should be so, but it was

not till seven years after that national jealousy and similar obstacles

could permit the fulfilment of the royal promise.

The leviathan was landed

at Leith, whence it was escorted back to its old lair on the Castle by

three troops of cavalry and the 73rd Perthshire Regiment, with a band of

pipers to head the procession. Standing alongside this ancient armament

on the King’s Bastion, one’s eyes roam over the buildings in which the

historical incidents that have been narrated took place, and looking

round one cannot fail to see how the ancient Castle formed a nucleus for

the great city which clusters round its base. In spite of all the sieges

which this venerable stronghold has weathered, the devastations to which

it has been subjected by successive conquerors, and, above all, the

total change in its defences consequent on the alterations introduced by

modern warfare, it can still boast of buildings dating further back than

any other in the ancient capital. Some portion of the battlements and

fortifications belong to a period before the siege of 1573, when that

brave soldier and adherent of Queen Mary Stuart, Sir William Kirkaldy of

Grange, surrendered after it had been reduced to a heap of ruins. In a

MONS MEG ON THE BOMB

BATTERY

report furnished to the

Board of Ordnance, from documents preserved in that department, it

appears that in 1574 (only one year after the siege) the governor,

George Douglas, of Parkhead, repaired the walls and built the Half-Moon

Battery on the site of David’s great tower. A small tower, with

crow-stepped gables, built to the east of the draw-well, and forming the

highest point of the fore-wall just north of the Half-Moon Battery, is,

Daniel Wilson says, without doubt a building erected long before

Cromwell’s time, and to all appearance coeval with the battery, but it

is quite obvious that this little tower is older than even Wilson

thought. Considerable portions of the western fortifications of the

parapet wall, the port-holes in the Half-Moon Battery, and the

ornamental coping and embrasures of the north and east batteries are of

much later date.

The approach to the

Castle has undergone various alterations from time to time. The

Esplanade as one sees it to-day was formed with the earth removed from

the site of the Royal Exchange, which was commenced in 1753. Previous to

this date the old roadway to the Castle from the 'treves’ on Castle Hill

descended abruptly into the hollow which the Esplanade now covers and

ascended by 'Nova Scotia’ to the Spur, which was a triangular defence

outside and below the steep ascent to the old gateway.

An interesting bird’s-eye

view taken in 573 and printed in the Bannatyne Miscellany represents the

Castle as rising abruptly on the east side this also appears in all the

earlier maps of Edinburgh. The entrance to the fortress appears to have

been by a long flight of steps, and a similar approach is often shown

immediately within the drawbridge. There seems to have been an ancient

and highly ornamental gateway near the guard-room, decorated with

pilasters, with deeply carved mouldings over the arch, and surmounted

with a curious oblong piece of sculpture in high relief showing Mons

Meg, with other ordnance and ancient weapons. This old gateway

unfortunately had to be removed at the beginning of the present century,

as it was too narrow to admit modern carriages and wagons. The present

gateway was erected on its site, and the old carved panels have been

placed in the walls.

The inner gateway to the

west of the one just referred to is an ancient piece of architecture.

Upon the walls of the deeply arched vault, leading into the Argyll

Battery, one can find openings for the two portcullises, also traces of

the hinges of several successive gates that once closed this important

opening. The building immediately over the long vaulted archway is the

Constable Tower or State Prison, which has figured so much in the story

of the Castle. This was the gloomy prison in which both the Marquis and

the Earl of Argyll were confined previous to their execution, and from

which the latter had so romantic an escape, only to be once more dragged

back to await the fatal day. Here it was, too, that the brave adherents

to the House of Stuart suffered the penalty of the law. Inside one will

notice the groove round the vaulted roof where once a portcullis was

lowered to divide the gloomy apartment, with its immensely thick walls

and grated windows overlooking a magnificent panorama of the surrounding

country. The last State prisoners lodged here were Watt and Downie, who

were accused of high treason in 1794. Watt was condemned to death, and

it was intended that he should be executed on the Castle Hill—the place

of execution for traitors—but it was thought this might be looked upon

as indicating fear on the part of the Government, so he was taken to the

Lawn-market and dispatched there in the presence of a great crowd.

The State Prison was

restored by the late Mr. William Nelson, the well-known publisher. The

panel above the lower end of the archway now containing the Scottish

Lion Rampant was recarved after remaining disfigured from the time of

the Commonwealth, when Cromwell ordered its destruction ; the two hounds

on either side are the arms of the Gordons, and these were spared ;

above the royal arms may still be seen the hearts and mullets of the

Douglases. On the left, high up on the wall, is the memorial tablet to

the brave Kirkaldy of Grange, who, as already related, held the Castle

in the interest of Mary Stuart.

Another object of

interest is the Governor’s house, which was probably built in the reign

of Queen Anne, and close by is the Armoury. To the west of these

buildings is the Postern, very near the site of the ancient and

historical one where, as is recorded on a memorial tablet over the

gateway, 4 Bonnie Dundee ’ held his conference with the Duke of Gordon

when on his way to raise the Highland clans for King James, while the

Convention was assembled in the Parliament House and was arranging to

settle the Crown upon William and Mary. It was through here, too, that

the body of the pious Queen Margaret was smuggled whilst Donald Bane and

his band of wild western Highlanders were battering at the gates on the

east side in the hope of capturing young Edgar, the second son of

Malcolm.

On the highest and almost

inaccessible part of the rock overlooking the Old Town, where the smoky

chimneys of the Grassmarket lie two hundred or more feet below, is the

ancient royal palace, forming the south and east sides of a quadrangle

known as the Grand Parade, or Crown Square. The chief portion of the

southern side of the square consists of a large ancient building called

Magne Camere, or Great Hall, erected, according to the Exchequer Rolls,

in 1434. A similar hall, however, some suppose had existed on the spot

at a much earlier date. This was the great ceremonial chamber of the

royal palace in which Parliaments assembled and banquets were held. It

was here that James II of Scotland was proclaimed King, and the

treacherous Crichton and Livingstone entertained the two Douglases at

the fatal c Black Dinner.’ Here also Queen Mary entertained her riotous

nobles with the idea of reconciling them, and James VI feasted the

nobility of both countries. Here the unfortunate Charles held his

coronation banquet, and in 1648 the Marquis of Argyll, in the same hall,

entertained Cromwell and discussed the necessity of taking away the

King’s life. These are but a few of the notable events that took place

within the walls of this ancient hall, which was connected with the

royal palace by a narrow staircase at the east end.

When, after the Union in

1707, the Castle ceased to be used as a royal residence the Hall fell

into disrepair. Subsequently it was divided into floors and partitioned

off into rooms for the accommodation of the soldiers. It was also used

for many years as the military hospital, and the writer remembers the

time when convalescents used the square as a recreation ground. Some

years later the authorities, under the pressure of antiquarians, took

steps to ascertain the original condition of the building.

By some good fortune, in

1883, Colonel Gore Booth, of the Royal Engineers, discovered a staircase

communicating with the hall from the dungeons underneath. This aroused

curiosity, and Lord Napier and Ettrick, with Colonel Gore Booth,

examined the upper floors and the original roof above the ceiling, and

found the rafters and cross-pieces, which stand in their original

position, in good preservation. On the upper floor the carved timbers of

the ancient roof were apparent, descending through the modern ceiling

and resting probably on their proper supports below the level of the

floor. Only one of these supports, however, was visible in the

staircase, and it consisted of a stone corbel sculptured with a fine

female head, and adorned on the sides with thistles boldly wrought. Mr.

William Nelson, who had already restored the State Prison, undertook the

restoration of the Banqueting Hall. The architect, in his examination of

the fabric, after the flooring and partitions had been removed,

discovered that the Hall had been re-roofed about sixty years after the

date of its erection. He found that the main timbers of the roof were

supported by stone corbels embedded in the modern flooring. These

corbels remain as they were found. Two of them bear heads which

represent James IV and his Queen Margaret. The others are carved with

cherubs, and fleurs-de-lis shields bearing the royal Scottish arms

surmounted by a crown, lion head, and emblems of plenty. There are

shields on three of the corbels bearing the initials J. R. (Jacobus

under an arabic figure four in its old form, which resembles a St.

Andrew’s cross with a bar along the top. The corbels are carved with the

design of the thistle and rose on either side, emblematic of the

Scottish King and his Tudor Queen; on the faces of two are cut the same

decoration. One has the monogram I.H.S., and in the centre a cross said

to represent King James’s connexion with the Church as a canon of the

Cathedral of Glasgow. The great timber roof of the Hall is just as it

was centuries ago. The timbers terminate at the foot with carved

shields, on which are emblazoned the armorial bearings of the governors

and constables of the old fortress from 1107 to 1805.

The beautiful windows

lighting the north and south sides were restored, and bear colour

designs of the arms of Scottish sovereigns from the time of Malcolm

Canmore, 1057, to James VI. On a small window in the west gable appear

the royal arms of Scotland. Opposite to this is the original c luggie ’

or eyelet of the private stair leading to the royal palace already

referred to. The 6 luggie ’ has been covered with a wrought-iron grille.

Through it a listener on the stair could see and hear what was taking

place in the Hall. The old fireplace was discovered amongst a heap of

modern masonry, but it was in such a state of dilapidation that it had

to be reconstructed, and now makes a fine if rather large centre-piece

at the east gable. It is of massive design, decorated with carved shafts

supporting a richly carved and moulded lintel and stone canopy. The

projecting angles have corbels beautifully carved with classical figures

representing 'The Chase,’ 'Music,’ 'Feasting,’ and 'Law.’ These corbels

support emblematical figures suggested by Dunbar’s poem of 'The 'Tkrissill

and the Rois, written in honour of the marriage of James IV to Princess

Margaret, and represent c May,’ 'Flora,’ 'Aurora,’ and 'Venus.’

And as the bits full soune

ofcherarchy

The fowl is song throw confort of the licht;

The birdis did with oppin vocis cry,

O luvaris fo, away thow dully nycht,

And welcum Day that confortis every wicht;

Haill May, ha ill Flora, haill Aurora schene,

Hail I Princes Nature, haill Venus luvis quene.

The walls are covered in

their lower parts with carved oak panelling, like that employed on the

gallery and screen, and above are hung in artistic groups the arms and

armour which were brought from the old Armoury and also from the Tower

of London. These old weapons, which date from the sixteenth century

comprise such pieces as blunderbusses, Highland targets and pikes of

various designs from the field of Culloden, Lochaber axes, Highland

flint-lock pistols, and fine suits of steel armour.

From the timbers of the

roof are suspended the colours which belonged to the old Scottish

regiments, and they form an interesting part of the exhibition, for some

of the regiments are now extinct, and these relics are all that is left

of them. They include the colours of the old Midlothian Regiment of

1775, the Inverness Local Militia, 3rd Regiment, 1775, t^le Galloway

Light Infantry (embroidered in silk in the centre of which is the Lion

Rampant of Scotland, surrounded by a three-quarter Union wreath and

crown, with the motto, Senes Callatus Callovidive sub hoc signo vinces),

the Ayrshire Riflemen, the Linlithgowshire Local Regiment, the 9th

Battalion Royal Veterans, the Dumbartonshire, the Fifeshire, the

Roxburgh and 4th Lanark Highlanders, the Haddingtonshire and 4th

Lanarkshire, the 2nd East Royal Perthshire, the and and 3rd Edinburgh

Local Militia, the Kincardineshire, Forfarshire, 5th Aberdeenshire, and

the Royal Perth and Edinburgh Highlanders. Most of these colours, some

of which are the King’s as well as the regimental, are of the period of

George III.

At the east end, in front

of the great fireplace, stands the modern gun-carriage which not only

bore the remains of Queen Victoria from Osborne to Cowes, but also did

similar duty in the funeral procession of King Edward VII. From the

windows the view can hardly be surpassed. Immediately below are the old

houses of the Grassmarket and the West Port, rapidly disappearing,

beyond which rise the new buildings of Edinburgh’s Art School. Slightly

farther to the east rise the fine towers of George Heriot’s Hospital, a

lasting monument to the jeweller to James VI who left his fortune for

the benefit of the orphans of burgesses and freemen, and in the distance

is Blackford Hill, whence Sir Walter Scott pictured Marmion’s view of

Edinburgh:

Still on the spot Lord

Marmion stay'd

For fairer scene he ne'er survey'd.

W^hen sated with the martial show

That peopled all the plain below,

The wandering eye could o'er it go

And mark the distant city glow

With gloomy splendour red;

For on the smoke- wreaths, huge and slow,

That round her sable turrets flow,

The morning beams were shed,

And tinged them with a lustre proud,

Like that which streaks a til under- cloud.

Such dusky grandeur clothed the height,

JJ^here the huge Castle holds its state,

And all the steep slope down,

IVhose ridgy back heaves to the sky,

Piled deep and massy, close and highy

Mine own romantic town!

On the south-east is the

ancient castle of Craigmillar, where the Stuarts so many times

sojourned, and on the west the towers of Merchiston Castle, where lived

Sir Archibald Napier, Master of the Mint to James VI. Between these two

landmarks is the great expanse of the Burgh Muir, where the gallant

armies met preparatory to their long march to meet the English invaders,

and James III and IV from these same windows watched their standard of

the Scottish Lion, c the Ruddy Lion,’ unfurled and pitched in the famous

'Bore Stane.’

To the east and

south-east of the quadrangle we have the royal palace wherein have dwelt

kings and queens in all their splendour as far back, perhaps, as Malcolm

'Greathead,’ and there built in the wall is still the mystery which no

one seeks to decipher—and could not if he wished. Near the top of the

main building is a sculptured stone shield, which has suffered more,

perhaps, from the disciples of Cromwell than from the weather, with the

Lion Rampant surmounted by a crown, and over the doorway a stone tablet

with the cipher of Mary and Darnley carved in high relief on a scroll

with the '1566’ which commemorates the birth of the Prince whose fortune

was to unite England and Scotland under one Crown. Within is the room in

which he was born, once beautifully panelled, but abused in later years

by being turned into a canteen for the soldiers, who loafed in the very

chairs that the unfortunate Queen sat in. The antechamber is hung with

portraits and old engravings, one of which is of Mary Stuart when

Dauphiness of France, a copy by Sir John Watson Gordon from the original

in Dunrobin Castle by Farino, the Italian painter. It is supposed to

have been painted shortly after her marriage with Francis, when only

sixteen. Another portrait is of James VI, a copy from one painted by

Jacobus Jansen which is in the possession of the Hays of Dunse Castle \

the picture here was presented by the Right Hon. Lady Monson. There is

another portrait of Queen Mary which has been copied from the Bodleian

Library at Oxford, and a print by Lizars from the painting by Sheriff

representing the Queen’s escape from Loch Leven. This recalls the fact

that Queen Mary once planted a thorn tree on the island j it was cut

down in 1847, after casting its shadows on the castle for nearly three

hundred years. A piece of this tree has been presented by Sir Graham

Montgomery, and it now lies in the little room.

Besides the great

Banqueting Hall there was another much smaller one in the fortress, for

among items of the High Treasurer’s accounts we find, in 1516, “For

flooring the Lord’s Hall in David’s Tower, 10s.”

Some parts of the palace

are supposed to have been designed by Sir James Hamilton of Finnart, who

was architect to James V. A semi-octagonal tower of some height gives

access to the strongly vaulted bombproof room, once totally dark, in

which the Regalia were so long kept in obscurity. The room is now well

lighted, and the beautiful Crown of Scotland and the insignia of royal

office are exhibited to the visitor in a great grille. The window in the

wall facing the square was enlarged in 1848, and the ceiling panelled in

oak with shields in bold relief. Two barriers close the room, one a

grated door of gigantic strength like a portcullis.

In this same building

Queen Mary’s mother, the Catholic Mary of Guise, died in 1560, and,

having been refused funeral rites by the Protestant clergy, the body, it

will be remembered, was here allowed to lie for some considerable time

before it was removed to France.

Down in the depths are

the double tier of vaulted dungeons, secured by great iron gates and

heavy chains. It was in one of these that Kirkcaldy of Grange buried his

brother David Melville; also it was here that the poor French prisoners,

forty of whom slept in each chamber, were kept captive in the dim light

which came from the small loophole, which was then strongly guarded by

three ranges of iron bars. The north side of the quadrangle consists of

barrack-rooms, erected about the middle of the eighteenth century, and

occupying the site of an ancient church. The block was built from the

materials of the old building, which was of unknown antiquity. This is

described by Maitland as a very long and large ancient church, which,

from its spacious dimensions, was evidently not only built for the use

of the garrison, but for the service of the neighbouring inhabitants

before St. Giles’ Church was erected for their accommodation. The great

font and many beautifully carved stones were found built into the walls

of the barrack-rooms during some alterations. It was supposed to have

been built after the death of the pious Margaret, and dedicated to St.

Mary. It is mentioned by King I )avid I in his Holyrood charter as 'the

church of the capital of Edinburgh,” and is once more mentioned as such

in the charter of Alexander III and in several papal bulls, and the

“paroche kirk within the said Castell ” is distinctly referred to by the

Presbytery of Edinburgh in 1595. In 1753 it was divided into three

floors and used as a store for tents, cannon, and other munitions of

war. Near the old Postern is the site of the old butts, connected to the

garrison buildings by a winding stair. The rock at this part is defended

bv the western wall, Butes or Butts Battery, and a turret named the

Queen’s Post, which some people think stands near the site of St.

Margaret’s Tower.

From the ancient postern

gate there is an ascent by steps behind the banquette of the bastions to

Mylne’s Mount, named after the master gunner, where there is a cradle

for a bale-fire, which could be seen from Fife and Stirling. The

fortifications are built in an irregular way, with occasional strong

stone turrets, and embrasures which are in readiness for mounting sixty

pieces of ordnance. “The Old Castle Company” was a corps of Scottish

soldiers raised in January 1661, and formed a permanent part of the

garrison until 1818, when they were incorporated in one of the thirteen

veteran battalions embodied in that year, along with the ancient guard

of Mary of Guise which garrisoned the castle of Stirling.

The Castle has a claim on

the Canongate churchyard as a burial-place for its soldiers, as it is

within the parish of Holyrood, but repeatedly during the sieges and

blockades the dead have been buried within the walls. In 1745 nineteen

soldiers and three women, it is believed, were laid to rest on the

summit of the rock, near to St. Margaret’s Chapel. The chapel, by the

way, originally built by the pious Queen during her residence in the

Castle, was for some time entirely lost sight of as an oratory, having

been converted into a powder magazine ; but happily in 1853 the old

relic was once more restored to its more sacred uses. It is not only the

most ancient chapel in the country, but the smallest. |