|

ABERCROMBIE, or

ABERCROMBY,

a surname derived from a barony of that name in Fifeshire, erected in a

district originally named Abercrombie, aber meaning beyond, and

crambie, the crook, in allusion to the bend or crook of Fifeness. The

parish, until recently called St. Monance, and now Abercromby, was known

by the name of Abercrombie so far back as 1174. The Abercrombies of that

ilk were esteemed the chiefs of the name until the seventeenth century,

when that line became extinct, and Abercromby of Birkenbog, in Banffshire,

became the head of the clan of Abercromby. In 1637 Alexander Abercromby of

Birkenbog was created a baronet of Scotland and Nova Scotia, and

distinguished himself as a royalist during the civil wars. The baronetcy

is still in the family.

ABERCROMBIE,

Baron, an extinct peerage, bestowed by Charles I., by letters patent dated

at Carisbrooke castle 12th December 1647, on Sir James Sandilands of St.

Monance, or Abercrombie, in Fife, descended from James Sandilands

belonging to the noble houae of Torphichen. In 1649 Lord Abercrombie

disposed of his property in Fife, including St. Monance, and the castle of

Newark, to Lieutenant-general David Lesly, who took his title of Lord

Newark from thence. Lord Abercrombie married Lady Agnes Carnegie, second

daughter of David, first earl of Southesk, and by her he had a son, James,

second Lord Abercrombie, who dying without issue in 1681, the title became

extinct.

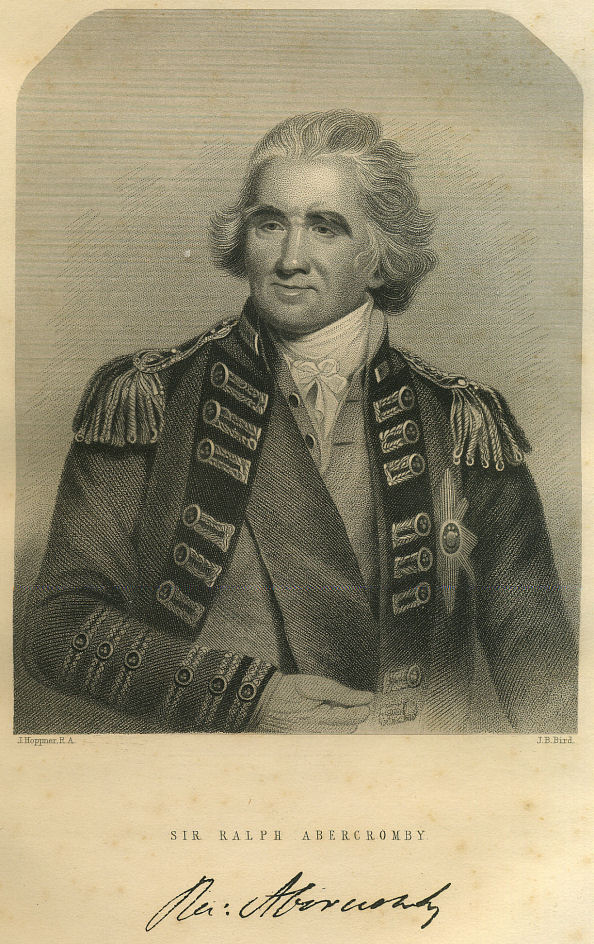

ABERCROMBY,

of Aboukir and Tullibody, Baron, a title in the peerage of the United

Kingdom, conferred in 1801 on Mary Anne, widow of the celebrated Sir Ralph

Abercromby, immediately after her husband’s death at this battle of

Alexandria, with remainder to the heirs, male of the deceased, general.

Baroness Abercromby died in 1821, and was succeeded by her eldest son,

George, a barrister at law, first baron. On his death in 1843, Colonel

George Ralph Abercromby, his son, born in 1800, became second baron. Sir

Ralph Abercromby, born in 1838, became third baron. See ABERCROMBY, Sir

RALPH.

ABERCROMBIE, JOHN,

M.D., an

eminent physician, and moral and religious writer, was born in Aberdeen,

12th October, 1780. His father was minister of the East church of that

city. After having completed his literary edtication in his native city,

he was sent to the university of Edinburgh, to prosecute his studies for

the medical profession. The celebrated Dr. Alexander Monro was at that

time professor of anatomy and surgery there and the subject of this memoir

attended his lectures.

In 1803, being then

twenty-three years of age, Dr. Abercrombie began

to practise as a physician in Edinburgh. He soon acquired a high

reputation, and became extensively known to his professional brethren

through the medium of his contributions to the ‘Medical and Surgical

Journal.’ On the death of the celebrated Dr. Gregory in 1821, Dr.

Abercrombie at once took his place as a consulting physician. He was also

named physician to the king for Scotland, an appointment which, though

merely honorary and nominal, is usually conferred on the physician of

greatest eminence at the time of a vacancy. He subsequently held, till his

death, the office of physician to George Heriot’s Hospital. In 1828, he

published a treatise on the ‘Diseases of the Brain and Nervous System,’

and soon after an essay on those of the ‘Abdominal Organs,’ both of which

rank high among professional publications. In 1830 he appeared as an

author in a branch of literature entirely different, and one involving the

treatment of subjects in the highest department of philosophy and

metaphysical speculation, having published in that year his able work, in

8 volumes, on the ‘Intellectual Powers.’

In

1833 he produced a work of a similar kind, on ‘The Philosophy of the Moral

Feelings,’ also in 8vo. In 1832, during the prevalence of the cholera, he

had published a medical tract entitled ‘Suggestions on the Character and

Treatment of Malignant Cholera.’ in 1834 he published a pamphlet entitled

‘Observations on the Moral Condition of the Lower Orders in Edinburgh.’

The same year appeared an address delivered by him at the Fiftieth

Anniversary of the Destitute Sick Society, Edinburgh. He was also the

author of Essays on the ‘Elements of Sacred Truth,’ and on the ‘Harmony of

Christian Faith and Character;’ besides other writings which have been

comprised in a small volume entitled ‘Essays and Tracts.’ Of writings so

well known, and so very highly esteemed, as proved by a circulation

extending, as it did in some, even to an eighteenth edition, it were

useless to speak in praise either of their literary or far higher merits.

But, distinguished as he was, both professionally and as a

writer in the highest departments of philosophy, it was not

exclusively to his great fame in either respect, or in both, that he owed

his wide influence throughout the community in which he lived. His name

ever stood associated with the guidance of every important enterprise,

whether religious or benevolent,—somehow he provided leisure to bestow the

patronage of his attendance and his deliberative wisdom on many of the

institutions of Edinburgh, and, with a munificence which has been rarely

equalled, ministered of his substance to the upholding of them all. He

valued money so little, that he often declined to receive it, even when

the offerer urged it, as most justly his own. His diligence and

application were so great that whoever entered his study found him intent

at work. Did they see him travelling in his carriage, they could perceive

he was busy there. (Obituary notice in Witness newspaper.)

In 1834

the university of Oxford conferred upon him the degree of M.D., which he

had long previously obtained from the university of Edinburgh. In 1835 he

was chosen by the students lord rector of Marischal college, Aberdeen. Dr.

Abercrombie died suddenly at Edinburgh, from rupture of an artery in the

region of the heart, on the 14th of November, 1844. Distinguished alike as

a physician, an author, a benefactor of the poor, and a sincere Christian,

his loss was universally lamented. He was buried in the West Churchyard,

Edinburgh, where a monument with a medallion has been erected to his

memory, the former bearing the following inscription:—"In memory of John

Abercrombie, M.D., Edin. and Oxon., Fellow of the Royal colleges of

Physicians and Surgeons, Edinburgh, Vice-president of the Royal Society of

Edinburgh, and first Physician to the Queen in Scotland, born xii. Oct.

MDCCLXXX. a life very early devoted to the service of God, occupied in the

most assiduous labours, and distinguished not more by professional

eminence than by personal worth and by successful authorship on the

principles of Christian morals and philosophy, it pleased God to translate

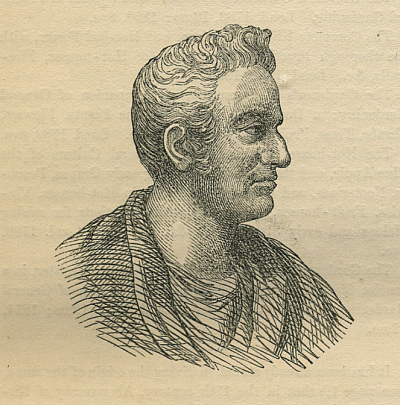

him suddenly to the life everlasting xiv. Nov. MDCCCXLIV." Annexed is a

copy of the medallion, which embodies as true a likeness of Dr.

Abercrombie as stone or wood can convey.

The

procession at his funeral was one of the largest ever seen in Edinburgh.

It was joined by the members both of the Royal College of Physicians, and

the Royal College of Surgeons, as well as by the Free Church presbytery of

Edinburgh and the commission of the General Assembly of the Free Church,

and by many professional brethren from a distance. Dr. Abercrombie married

in 1808 Agnes, only child of David Wardlaw, Esq., of Netherbeath in

Fifeshire, and had eight daughters, one of whom died at the age of four.

Seven daughters survived him, the eldest of whom became the second wife of

the Rev. John Bruce, minister of Free St. Andrew’s church, Edinburgh, in

whose congregation Dr. Abercrombie was an elder, and who preached his

funeral sermon, which was afterwards published. The estate of Netherbeath

descended to Mrs. Bruce. The following is a list of Dr. Abererombie’s

publications:

Diseases

of the Brain and Nervous System, 8vo, 1828.

Diseases of the Abdominal Organs, 8vo, 1829.

The Intellectual Powers, 8vo, 1830.

Suggestions on the Character and Treatment of Malignant Cholera, 8vo,

1832.

The Philosophy of the Moral Feelings, 8vo, 1833.

Observations on the Moral Condition of the Lower Orders in Edinburgh, 8vo,

1834.

Address delivered at the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Destitute Sick

Society, Edinburgh, 1835.

Mental Culture, 18mo, being the Address delivered to the students of

Marischal College when he was elected Lord Rector of that university,

1835.

The Harmony of Scripture Faith and Character, 18mo, 1836.

Think on these Things, 18mo, 1839.

Messiah our Example, 18mo, 1841.

The Contest and the Armour, 18mo, 1841.

The Elements of Sacred Truth, 18mo, 1844.

Essays

and Tracts, including the two last works and some other writings on

similar subjects, 8 volumes, 1844, 1847.

ABERCROMBIE, JOHN,

conjectured by Dempster, in his Hist. Eccl. Scot., to have been a

Benedictine monk, was the author of two energetic treatises in defence of

the Church of Rome against the principles of the Reformers, entitled

‘Veritatis Defenslo,’ and ‘Haeresis Confusio.’ He flourished about the

middle of the sixteenth century.

ABERCROMBIE, PATRICK,

physician and historian, third son of Alexander Abercrombie of Fetterneir,

Aberdeenshire, a branch of the Birkenbog family of that name, was born at

Forfar in 1656, and took his medical degrees at St. Andrews in 1685. His

elder brother, Francis Abererombie of Fetterneir, on his marriage with

Anna, Baroness Sempill, was, in July 1685, created by James VII. Lord

Glassford, under the singular restriction of being limited for his own

life. After leaving the university, Patrick travelled on the continent,

and on his return to England, embracing the Roman Catholic religion, he

was appointed physician to James VII.; but at the Revolution was deprived

of his office, and for some years lived abroad. Returning to his native

country, he afterwards devoted himself to the study of national

antiquities. In 1707 he gave to the world a translation of M. Beauge’s

rare French work, ‘L’Histoire de Ia Guerre d’Ecosse,’ 1556, under the

title of ‘The Campaigns in Scotland in 1548 and 1549,’ which was reprinted

in the original by Mr. Smythe of Methveu for the Bannatyne Club, in 1829,

with a preface containing an account of Abercrombie’s translation. His

great work, however, is ‘The Martial Achievements of the Scots nation, and

of such Scotsmen as have signalized themselves by the Sword’ in two

volumes folio, the first published in 1711, and the second in 1715. He

also wrote the ‘Memoirs of the family of Abercrombie.’ Dr. Abercrombie

died in poor circumstances in 1716; some authorities say 1720, and others

1726. The following is a list of his works.

The Advantages of the Act of Security, compared with those of the intended

Union; founded On the Revolution Principles, published by Mr. Daniel De

Foe. Edin. 1707, 4vo.

A

Vindication of the same, against Mr. De Foe. Edin. 1707, 4vo.

The History of the Campaigns 1548 and 1549, between the Scots and the

French on the one side, and the English and their foreign auxiliaries on

the other. From the French of Beauge, with a Preface, showing the

Advantages which Scotland received by the Ancient League with France, and

the mutual assistance given by each kingdom to the other. Edin. 1707, 8vo.

The Martial Achievements of the Scots nation, being an Account of the

Lives, Characters, and Memorable Actions of such Scotsmen as have

signalized themselves by the Sword, at home and abroad. Edin. 1711—1715. 2

vols. fol.

ABERCROMBIE, JOHN,

an eminent horticulturist; and author of several horticultural works, was

the son of a respectabie gardener near Edinburgh, where he was born about

the year 1726. In his eighteenth year he went to London, and obtained

employment in the royal gardens. His first work, ‘The Gardener’s

Calendar,’ was published as the production of Mr. Mawe, gardener to the

duke of Leeds, who received twenty guineas for the use of his name, which

was then well known. The success of that work was so complete, that

Abercrombie put his own name to all his future publications; among which

may be mentioned,

‘The

Universal Dictionary of Gardening and Botany,’ 4vo, ‘The Gardener’s Vade

Mecum,’ and other popular productions. He died at Somerstown, London, in

1806, aged 80. A list of his works is subjoined.

The

Universal Gardener and Botanist, or a General Dictionary of Gardening and

Botany, exhibiting, in Botanical Arrangement, according to the Linnnaean

system, every Tree, Shrub, and Herbaceous Plant that merit Culture, &c.

Lond. 1778, 4th.

The

Garden Mushroom, its Nature and Cultivation, exhibiting full and plain

directions for producing this desirable plant in perfection and plenty.

Lond. 1779, 8vo. New edition enlarged, 1802, 12mo.

The

British Fruit Garden, and Art of Pruning; comprising the most approved

Methods of Planting and raising every useful Fruit Tree and Fruit-bearing

Shrub. - Lond. 1779, 8vo.

The

Complete Forcing Gardener, for the thorough Practical Management of the

Kitchen Garden, raising all early crops in Hot-beds, and forcing early

Fruit, &c. Lond. 1781, 12mo.

The Complete-Wall-tree-Pruner, &c. Lond.- 1788, 12mo.

The

Propagation and Botanical Arrangement of Plants and Trees, useful and

ornamental. Lond. 1785, 2 vols. 12mo.

The

Gardener’s Pocket Dictionary, or a Systematical Arrangernent of Trees,

Herbs, Flowers, and Fruits, agreeable to the Linnaean Method, with their

Latin and English names, their Uses, Propagation, Culture, &c. Lond. 1786,

3 vols. 12mo.

Daily

Assistant in the Modern Practice of English Gardening for every Month in

the Year, on an entire new plan. Lond. 1789, 12mo.

The

Universal Gardener’s Kalendar, and System of Practical Gardening; Lond.

1789, 12mo; 1808, 8vo.

The Complete Kitchen Gardener and Hot—bed Forcer, with the thorough

Practical Management of Hot-houses, Firewalls, &c. Lond. 1789, 12mo.

The

Gardener’s Vade-mecum, or Companion of General Gardening; a Descriptive

Display of the Plants, Flowers, Shrubs, Trees, Fruits, and general

Culture. Lond. 1789, 8vo.

The

Hot-house Gardener, or the general Culture of the Pine Apple, and the

Methods of forcing early Grapes, Peaches, Nectarines, and other choice

Fruits in Hot—houses, Yin— cries, Fruit —houses, Hot—walls, with

Directions for raising Melons and early Strawberries, &c. Plates. Lond.

1789, 8vo.

The

Gardener’s Pocket Journal and Annual Register, in a concise Monthly

Display of all Practical Works of General Gardening throughout the year.

Lond. 1791, 12mo; 1814, 12mo.

It has been already stated, in giving the origin of the name, (see page

1,) that in the 17th century, Abercromby of Birkenbog in Banffshire,

became the chief of the name of Abercromby. Alexander Abercromby of

Birkenbog was grand falconer in Scotland to King Charles I. In 1636 his

eldest son, Alexander, was created a baronet of Nova Scotia, and took an

active part against King Charles in the civil wars of that period. From

the pedigree of the family it appears that Sir Alexander Abercromby of

Birkenbog, the, first baronet, had two sons. The eldest; James, succeeded

his father. Alexander, the second son, succeeded his cousin George

Abercromby of Skeith, in the estate of Tullibody, in Clackmannanshire,

formerly a possession of the earls of Stirling. This Alexander was the

grandfather of, the celebrated military commander, Sir Ralph Abercromby,

and the second of the name of Abercromby who possessed Tullibody. The most

eminent of this family were General Sir Ralph Abercromby; and his two

brothers, Alexander, Lord Abereromby, a judge of the court of session; and

General Sir Robert Aberàromby, K.C.B.; of all three notices are here

given.

ABERCROMBY, SIR RALPH, K.B.,

a distinguished

general, was the eldest son of George Abercromby, of Tullibody, in

Clackmannanshire, by Mary, daughter of Ralph Dundas, Esq. of Manor. His

father was born in 1705, passed advocats in 1728, and died June 8, 1800,

at the advanced age of ninety-five, being the oldest member of the college

of justice. . He was one of the early patrons of David Allan, the

celebrated painter, by whose aid, as mentioned in the life of that artist,

the latter was enabled to proceed to Rome and to prosecute his studies

there for sixteen years.

His son Ralph was born on the 7th of October, 1734, in the old mansion of

Menstrie, then the ordinary residence of his parents, near the village of

that name which, lies at the southern base of the Ochil hills, on the

boundary between the parish of Alloa in Clackmannanshire, and the

Perthshire part of the parish of Logie. The day of his birth has not been

inserted in the session books of the parish of Logie, but the following is

an extract from the register of his baptism: "A. D. 1734, October 26th,

Bap. Ralph, lawful son to George Abercromby, younger of Tullibody, and

Mary Dundas his lady."

Menstrie house, in which he was born, possesses a double interest from its

having been, in the beginning of the seventeenth century, the property and

residence of Sir William Alexander, the poet, afterwards created earl of

Stirling. Although not now inhabited by any of the Abercromby family, it

is still entire, and is pointed out to strangers as the birthplace of Sir

Ralph Abercromby. A woodcut representation of it is here given.

After the usual course of study, young Abercromby entered the army in

1756, as a cornet in the 3d regiment of dragoon guards. His commission is

dated 23d March of that year. In February 1760 he obtained a lieutenancy

in the same regiment; in April 1762 he was promoted to a company in the 3d

regiment of horse. In 1770 he became major, and in 1773,

lieutenant-colonel. In 1780 he was included in the list of brevet

colonels, and in 1781 he was appointed colonel of the 103d, or King’s

Irish infantry. This newly raised regiment was reduced at the peace in

1783, when Colonel Abercromby was placed on half-pay. In September 1787 he

became major-general.. In 1788, in which year he resided in George’s

Square, Edinburgh, he obtained the command of the 69th regiment of foot.

He was afterwards removed to the 6th. regiment, from that to the 5th, and

in November 1797 to the 7th regiment of dragoons.

He first served in the seven years’ war, and acquired great knowledge and

military experience in that service, before he had an opportunity of

distinguishing himself, which afterwards, when the opportunity came,

enabled him to be the first British general to give a check to the French

in the first revolutionary war. He has often been confounded with the

General Abercrombie who commanded the troops against the French at Crown

Point and Ticonderoga in America in 1758, but Sir Ralph at that period was

only a cornet of dragoons, and notwithstanding the mistake into which some

of his biographers have fallen, it is certain that he never was in

America.

In the year 1774, when lieutenant-colonel, he had been elected member of

parliament for Clackmannanshire, which county he continued to represent

till the next election in 1780, but never made any figure in parliament.

On the commencement of the war with France in 1792, he was employed in

Flanders and Holland, with the local rank of lieutenant-general,

and in the campaigns of 1793 and 1794 he served under the duke of York,

when he gave many proofs of his skill, vigilance, and intrepidity. He

commanded the advanced guard during the action on the heights of Cateau,

April 16, 1794. On this occasion he captured 85 pieces of cannon, and took

prisoner Chapny the French general. In the despatches of the duke of York

his ability and courage were twice mentIoned with special commendation.

In the succeeding October he received a wound at Nimeguen, and upon him

and General Dundas devolved the arduous duty of conducting the retreat

through Holland in the severe winter which followed. It has been remarked

that the talents, as well as the temper, of a commander are put to as

severe a test in conducting a retreat as in achieving a victory.

This was well illustrated in the case of General Abercromby. The guards

and the sick were committed to his care; and in the disastrous march from

Deventer to Oldensaal the hardships sustained by those under his charge

were such as the most consummate skill and judgment were almost inadequate

to alleviate, while the feelings experienced by the commander himself were

painful in the extreme. Harassed in the rear by a victorious enemy,

upwards of fifty thousand strong, obliged to conduct his troops with a

rapidity beyond their strength, through bad roads, in the most inclement

part of a winter more than usually severe,—the sick being placed in open

waggons, as, no others could be procured,— and finding it impossible to

procure shelter for his soldiers in the midst of the drifting snow and

heavy falls of sleet and rain, the anguish he felt at seeing their numbers

daily diminishing from the effects of cold, fatigue, and hunger, can

scarcely be described. About the end of March 1795, the British army,

which during the retreat had sometimes to halt, face and fight the enemy,

arrived at Bremen in a very reduced state, and thence embarked for

England. The judgment, patience, humanity, and perseverance shown by

General Abercromby in this calamitous retreat were equal to the occasion,

and received due acknowledgment.

In the autumn of 1795 General Abercromby was appointed, to succeed Sir

Charles Grey, as commander-in-chief of the troops employed against the

French in the West Indies. Previous to his arrival, the French

revolutionary army had made considerable exertions to recover their losses

in that quarter. They retook the islands of Guadaloupe and, St. Lucia,

made good their landing on Martinique, and hoisted the tricolour on

several forts in the islands of St. Vincent, Grenada, and Marie Galaute;

besides seizing the property of the rich emigrants who had fled thither

from France, to the amount of 1,800 millions of livres.

The expedition under General Abercromby was unfortunately prevented from

sailing until after the equinox, and several transports were lost in

endeavouring to clear the Channel. The remainder of the fleet reached the

West Indies in safety, and by the month of March 1796 the troops were in a

condition for active duty. A detachment of the army under Sir John Moore,

was sent against the island of St. Lucia, which was speedily captured,

though the attack on this island was attended with peculiar difficulties

from the intricate nature of the country. A new road was made for the

heavy cannon, and on the 26th of May 1796, the garrison surrendered. St.

Vincent was next subdued; and thence the commander-in-chief proceeded to

Grenada, where the fierce and enterprising Fedon was at the head of a body

of insurgents prepared to oppose the British. After the arrival of General

Abercromby, however, hostilities were speedily brought to a termination;

and on the 19th of June, full possession was obtained of every post in the

island, and the haughty chief Fedon, with his troops, was reduced to

unconditional submission. The British also became masters of the Dutch

colonies on the coast of Guiana, namely Demerara, Essequibo, and Berbice.

Early in the following year (1797) the general sailed, with a considerable

fleet of ships of war and transports, against the Spanish island of

Trinidad, and on the 16th of February approached the fortifications of

Gaspar Grande, under cover of which a Spanish squadron, consisting of four

sail of the line and a frigate, were found lying at anchor. On perceiving

the approach of the British, the Spanish fleet retired farther into the

bay. General Abercromby made arrangements for attacking the town and ships

of war early in the following morning. Dreading the impending conflict,

the Spaniards set fire to their own ships, and retired to a different part

of the island. On the following day the British troops landed, and soon

after the whole colony submitted to General Abercromby.

After an unsuccessful attack on the Spanish island of Puerto Rico, the

general returned to England the same year (1797) and was received with

every demonstration of public respect and honour. In his absence he had

been made a knight of the Bath and presented to the colonelcy of tbe Scots

Greys. On his return he was appointed governor of the Isle of Wight, and

was afterwards invested with the lucrative governments of Forts George and

Augustus. The same year he was raised to the rank of lieutenant-general,

which he had hitherto held only locally.

In 1798 Sir Ralph was appointed commander-in-chief of the forces in

Ireland, where the insurrectionary spirit, inflamed by promises of

assistance from France, was every day assuming a more serious form and

threatening to break out into open rebellion. Soon after his arrival,

finding that the disorderly conduct of some of the British troops had but

too much tended to increase the spirit of insubordination and discontent

that prevailed, he issued a proclamation, in which he lamented and

reproved the excesses and irregularities into which they had fallen, and

which, to use his own words, "had rendered them more formidable to their

friends than to their enemies," and declared his firm determination to

punish, with exemplary severity, any similar outrage of which they might

be guilty in future. He did not long retain his command in Ireland. The

inconveniences arising from the delegation of the highest civil and

military authority to different persons, had been felt to occasion much

perplexity and confusion in the management of public affairs, at that

season of agitation and alarm, and finding the service, under such

circumstances, disagreeable, Sir Ralph resigned the command, and the

Marquis Cornwallis, on becoming lord-lieutenant of Ireland, was appointed

his successor.

Sir Ralph was next nominated commander-in-chief of the forces in Scotland;

and for a short interval, the cares of his military duties were agreeably

blended with the endearments of his kindred and the society of his early

friends. During his residence in Edinburgh at this time, the military

spirit that generally prevailed rendered the occurrence of reviews

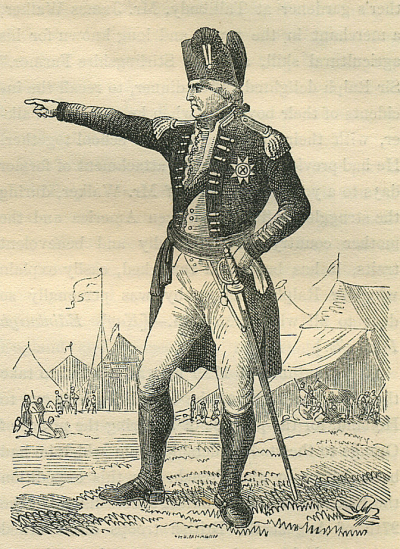

extremely popular among the inhabitants. The accompanying woodcut

represents Sir Ralph in the act of giving the word of command to the

troops.

It was at this period that the Lochiel Highlanders were inspected at

Falkirk by General Vyse, one of the major-generals of the staff in

Scotland, under Sir Ralph Abercromby, who was present at the inspection.

Cameron, the chief of Lochiel, married Sir Ralph’s eldest daughter Anne.

The regiment was ostensibly composed of Camerons, but there were enrolled

it its ranks, not only lowlanders, but even Englishmen and Irishmen. Some

laughable attempts at fraud in endeavouring to pass inspection are

related, but unless actually disabled, few objections were made, although

Scotsmen in general found a preference. "Where are you from?" said General

Vyse to a strange-looking fellow, who was evidently an Irishman, although

he endeavoured to make believe that he was Scotch. "From Falkirk, yir

honour, this morning," was the ready answer. His language betraying him,

the general demanded to know how he came over. "Sure I didn’t come in a

wheelbarrow !" The rising choler of the inspecting officer was speedily

soothed by the milder tact of Sir Ralph, who, seeing the man a fit

recruit, laughed heartily, and he was passed.

On this occasion Sir Ralph, during his stay in Falkirk, took up his

residence with the son of his late father’s gardener at Tullibody, Mr.

James Walker, a merchant in the town, and long known for his agricultural

skill, as "the Stirlingshire Farmer." Sir Ralph delighted, after dinner,

to recall the incidents of their boyhood, when he and Mr. Walker, with

their brothers, were at school together. He had previously shown the

attachment of former days to a younger brother of Mr. Walker, during the

struggle for liberty between America and the mother country. These kindly

and benevolent traits, it has been well remarked, easily explain why Sir

Ralph Abercromby was personally so dear to all who knew him.—(Kay’s

Edinburgh Portraits.]

In the autumn of 1799 he was selected to take the chief command of the

expedition sent out to Holland, for the purpose of restoring the prince of

Orange to the stadtholdership, from which he had been driven by the

French. In this expedition the British were at the outset successful. On

the 27th of August the British troops disembarked near the Helder point,

but were almost immediately attacked by General Daendells; after a

contest, which lasted from day - dawn till about five in the afternoon,

the Dutch were defeated, and retired, leaving the British in possession of

a ridge of sand hills which stretched along the coast from south to north.

Sir Ralph Abercromby resolved to attack the Heldef next morning, but the

enemy withdrew during the night, in consequence of which thirteen ships of

war and three Indiamen, together with the arsenal and naval magazine, fell

into the possession of the British. Admiral Mitchell, who commanded the

British fleet, immediately offered battle to the fleet of the Batavian

republic lying in the Texel, but the Dutch sailors refusing to fight

against those who were combating for the rights of the prince of Orange,

the whole fleet, consisting of twelve. sail of the line, surrendered to

the British admiral. This encouraging event, however, did not put an end

to the struggle.

The mass of the Dutch people held sentiments very different from those of

the sailors, and they refused to receive the British as their deliverers

from the yoke of France. On the morning of the 10th of September the Dutch

and French forces attacked the position of the British, which extended

from Petten on the German ocean to Oude-Sluys on the Zuyder-Zee. The onset

was made with the utmost bravery, but the enemy were repulsed with the

loss of a thousand men. From the want of numbers, however, Sir Ralph

Abercromby was unable to follow up this advantage, until the duke of York

arrived as commander-in-chief with a reinforcement of Russians, Bataviaus,

and Dutch volunteers, which augmented the allied army to nearly thirty-six

thousand men. Sir Ralph now served as second in command.

On the morning of the 19th September the army under the duke of York

commenced an attack on the enemy’s positions on the heights of Camperdown,

which was successful. The Russian troops, under General Hermann, made

themselves masters of Bergen, but beginning to pillage too soon, the enemy

rallied, and attacked them with so much impetuosity that they were driven

from the town in all directions. The British were in consequence compelled

to abandon the positions they had stormed, and to fall back upon their

former station. Another attack was made on the 2d of October. The conflict

lasted the whole day, and the enemy abandoned their positions during the

night. On this occasion Sir Ralph Abercromby had two horses shot under

him. Sir John Moore was twice wounded severely, and reluctantly carried

off the field, while the marquis of Huntly (the last duke of Gordon) who,

at the head of the 92d regiment, eminently distinguished himself, received

a wound from a ball in the shoulder.

The Dutch and French troops had taken up another strong position between

Benerwych and the Zuyder-Zee, from which it was resolved to dislodge them

before they could obtain reinforcements. A day of saligulnary fighting

ensued, which continued without intermission till ten o’clock at night

amid deluges of rain. The French republican general, Brune, having been

reinforced with six thousand additional men, and the ground which he

occupied being found to be impregnable, the duke of York resolved upon a

retreat. A convention was accordingly concluded with General Brune, by

which the British troops were allowed to embark for England.

In June 1800 Sir Ralph was appointed to the command of the troops, then

quartered in the island of Minorca, which had been sent out upon a secret

expedition to the Mediterranean. On the 22d of that month he arrived at

Minorca, and on the 23d the troops were embarked, and sailed for Leghorn.

They arrived there on the 9th of July, but in consequence of an armistice

having been concluded between the French and the Austrians, they did not

land there; but while part of the troops proceeded to Malta, the remainder

returned to Minorca. On the 26th of July Sir Ralph arrived again at that

island, where he remained till the 30th of August, when the troops were

again embarked; and on the 14th September the fleet, which consisted of

upwards of two hundred sail, under the command of Admiral Lord Keith,

came to anchor off Europa point in the bay of Gibraltar. After taking in

water at Teutan, the fleet, on the 3d of October, arrived off Cadiz, where

it was intended to disembark the troops, and orders were accordingly

issued for the purpose, but a flag of truce was sent from the shore, and

some negotiations took place between the commanders, in consequence of

which the orders for landing were countermanded.

After thus threatening Cadiz, and sailing about apparently without any

distinct destination, orders were at last received from England, for part

of the troops to proceed to Portugal, and the remainder to Malta, where

they arrived about the middle of November. The latter portion afterwards

formed part of the forces employed in the expedition to Egypt, with the

view of driving the French out of that country. The sailing backwards and

forwards of the fleet for so many months, seemingly without any definite

aim, so far from being indicative of want of design or weakness in the

councils of the government at home, as was believed and said at the time,

was no doubt intended to deceive the French as to the real object and

destination of the expedition.

From Malta the fleet, with Sir Ralph Abercromby and the troops on hoard,

sailed on the 20th December, taking with them 500 Maltese recruits,

designed to act as pioneers. On the 1st of January 1801, it rendezvoused

in the bay of Marmorice, on the coast of Caramania, where it remained till

the 23d of February, on which day, to the number of 175 sail, it weighed

anchor again; and on the 1st of March, it came in sight of the coast of

Egypt. On the following morning the fleet anchored in Aboukir bay, in the

very place where, a few years before, Admiral Nelson had added so signally

to the naval triumphs of Great Britain.

This was undoubtedly the most glorious period of Sir Ralph Abercromby’s

career. "All minds," says a contemporary historian, "were now anxiously

directed towards Egypt. It was a novel and interesting spectacle to

contemplate the two most powerful nations of Europe contending in Africa

for the possession of Asia. Not only to England and France, bat the whole

civilized world, the issue of this contest was of the utmost importance.

With respect to England, the difficulties to be surmounted were

proportioned to the magnitude of the object. The vizier, with his usual

irresolution, yet debated on the propriety of co-operation, while the

captain bashaw, who was at Constantinople, with part of his fleet,

inclined to treat with the enemy.

The English taking the unpopular side, that of the government, still less

was to be hoped from the countenance and support of the people, whom the

French had long flattered with the idea of freedom and independence. It

remained, also, to justify the breach of faith so speciously attributed to

this nation in the treaty of El Arish. These were serious obstacles to the

progress of the expedition in Egypt; but they were not the only obstacles.

- The expedition had to contend with an army habituated to the country,

respected at least, if not beloved, by the inhabitants, and flushed with

reputation and success; an army inured to danger; aware of the importance

of Egypt to their government; determined to defend the possession of it;

and encouraged in this determination, no less by the assurance of speedily

receiving effectual succours, than by the promise of reward, and the love

of glory."

The violence of the wind, from the 1st to the 7th of March, rendered a

landing impracticable; but the weather becoming calmer on the 7th, that

day was spent in reconnoitring the shore; a service in which Sir Sidney

Smith displayed great skill and activity.

In the meantime Bonaparte had sent naval and military reinforcements from

Europe, and the delay in the disembarkation of the British troops caused

by the state of the weather, enabled the French to make all necessary

preparations to receive them. Two thousand five hundred of the latter were

strongly intrenched on the sand hills near the shore, and formed, in a

concave figure, opposite the British ships. The main body of the French

army was stationed at and near Alexandria, within a few miles. At two

o’clock. on the morning of the 8th, the British troops began to assemble

in the boats, their fire-locks between their knees. A rocket from the

admiral’s ship gave the signal; and when all was ready, the boats, con

taining five thousand men, pulled in towards the shore, a distance of

about five miles. The silence was broken only by the sullen dip of the

oars. As soon as the boats came within reach, a most tremendous fire was

opened upon them from fifteen pieces of artillery placed on the ridge of

sand hills in front, besides the guns of Aboukir castle and the musketry

of 2,500 men. These completely swept the sea, and the falling of the balls

and shot is compared, by a contemporary writer, to the falling of a

violent hail-storm on the water. Two boats were sunk with all on board of

them. Each man had belts loaded with three days’ provisions, and a

cartouch-box with sixty rounds of ball cartridge.

It was nine o’clock when the rest reached land; and the French, who had

poured down in thousands to the beach, and even attacked the British in

the boats, were ready to receive them at the bayonet’s point. It was now

that their commander reaped the advantage of his precautionary discipline.

While anchored in the bay of Marmorice, he had caused the troops to

practise all the manmoevres of landing; so that, disembarkation having

become familiar to them, on reaching the shore, they leaped from the

boats, formed into line, mounted the heights, in the face of the enemy’s

fire, without returning a shot, charged with the bayonet the enemy

stationed on the summit, put them to flight, and seized their cannon. In

this service the 23d and 40th regiments, which first reached the shore,

particularly distinguished themselves; while the seamen, harnessing

themselves to the field artillery with ropes, drew them on shore, and

replied to the incessant roar of the hostile cannon with repeated and

triumphant cheers.

In vain did the enemy endeavour to rally his troops; in vain did a body of

cavalry charge suddenly on the guards at the moment of their debarkation.

The French gave way at all points, maintaining, as they retreated, a

scattered and inefficient fire. The boats returned to the ships for the

remaining part of the army, and before noon the landing was effected. It

not being deemed expedient, however, to bring on shore the camp stores;

the commander-in-chief and the troops, after having advanced three miles

into the country, alike slept in huts made of the date-tree branches.

The next

day the troops were employed in searching for water, in which they happily

succeeded; and the castle of Aboukir refusing to surrender, two regiments

were ordered to blockade it. On the 13th, Sir Ralph, desirous of forcing

the heights near Alexandria, on which a body of French, amounting to 6,000

men, was posted, marched his army to the attack.

After a severe contest, the French were compelled to retire to the heights

of Necopolis, which formed the principal defence of Alexandria. Anxious to

follow up the victory, by driving the enemy from his new position, Sir

Ralph ordered forward the reserve under Sir John Moore, and the second

line under General Hutchinson, to attack the heights, which were found to

be commanded by the guns of the fort. As they advanced into the open

plain, they were exposed to a most destructive fire, from which they had

no shelter; and having ascertained that the heights, if taken, could not

be retained, the attempt was abandoned, and the British army retired, with

considerable loss, to the position which was soon to be the theatre of Sir

Ralph’s last victory;—that, namely, from which the enemy had been driven,

comprising a front of more than half-a-mile in extent, with their right to

the sea, and their left to the canal of Alexandria and Lake Maadie,

thus cutting off all communication with the city, except by- way of the

desert. The loss of the British, on that unfortunate day, in killed and

wounded, was upwards of 1,000, and General Abercromby himself, on this

occasion, had a very narrow escape. His horse being shot under him, he

became surrounded by the enemy’s cavalry, and was rescued only by the

devoted intrepidity of the 19th regiment. After the 13th, Aboukir castle,

which had hitherto been only blockaded, was besieged, and on the 18th the

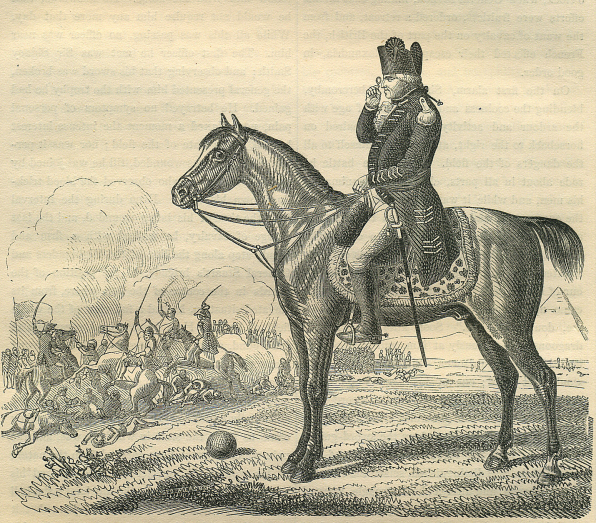

garrison surrendered. The annexed woodcut represents the general viewing

the army encamped on the plains of Egypt, a short time before his lamented

death. It is very characteristic of him, and though the glass at his eye

may indicate that age had begun to affect his sight, the erectness of his

figure shows that, notwithstanding his long and active career, advancing

years and the hard services in which he had been engaged, had left their

traces but lightly on his frame.

The French commander-in-chief, General Menon, having arrived from Cairo,

with a reinforcement of 9,000 men, early on the morning of the 21st of

March, was fought the decisive battle of Alexandria, in which, after a

sanguinary aad protracted struggle, the British were victorious, General

Menon being obliged to retreat with a loss of between three and four

thousand men, including many officers, and three generals killed. The loss

of the British was also heavy, and this was the last field of the victor,

for here Sir Ralph Abercromby received his death-wound.

Meaning

to surprise the British, the French commander attacked their position

between three and four o’clock in the morning, with his whole force,

amounting to about twelve thousand men. The action was commenced by a

feigned attack on the left, while the main strength of the enemy was

directed against the right wing. of the British army. They advanced in

columns, shouting "Vive la France!" "Vive Ia Republique!" but they were

received with steady coolness by the British troops, who, warned the

previous evening, by an Arab chief, of the intentions of the French

general, were in battle array by three o’clock, and prepared to receive

the onset of the enemy. The contest continued with various success until

eight o’clock, when General Menou, finding that all his efforts were

fruitless, ordered a retreat, and from the want of cavalry on the part of

the British, the French effected their escape to Alexandria, in good

order.

On the first alarm, Sir Ralph Abercromby, blending the coolness and

experience of age with the ardour and activity of youth, repaired on

horseback to the right, and exposed himself to all the dangers of the

field. During the battle he rode about in all parts, cheering and

animating his men, and while it was still dark he got among the enemy, who

had already broken the front line and fallen into the rear. Unable to

distinguish the French soldiers from his own, he was only extricated from

his dangerous situation by the valour of his troops. To the first British

soldier who came up to him he said, "Soldier! if you know me, don’t name

me." Soon after, two French dragoons rode furiously at him, and attempted

to lead him away prisoner. Sir Ralph, however, would not yield; one of his

assailants made a thrust at his breast, and passed his sword with great

force under the general’s arm. Although severely bruised by a blow from

the sword-guard, Sir Ralph, with the vigour and strength of arm for which

he was distinguished, seized the Frenchman’s weapon, and after a short

struggle, wrested it from his hand, and turned to oppose his remaining

adversary, who, at that instant, was shot dead by a corporal of the 42d,

who had witnessed the danger of his commander, and ran up to his

assistance; on which the other dragoon retired.

Although Sir Ralph, early in the action, had been

wounded in the thigh by a musket ball, he treated the wound as a trifle,

and continued to move about, and give his orders with his characteristic

promptitude and clearness. On the retreat of the enemy he fainted from

pain and the loss of blood. His magnanimous conduct, both during the

battle and after it, is thus detailed by the late General David Stewart,

of Garth, who was an eye-witness to it. After describing Sir Ralph’s

rencontre with the French dragoons, he continues: "Some time after the

general attempted to alight from his horse; a soldier of the Highlanders,

seeing that he had some difficulty in dismounting, assisted him, and asked

if he should follow him with the horse. He answered, that he would not

require him any more that day. While all this was passing, no officer was

near. him. The first officer he met was Sir Sidney Smith; and observing

that his sword was broken, the general presented him with the trophy he

had gained. He betrayed no symptom of personal pain, nor relaxed a moment

the intense interest he took in the state of the field; nor was it

perceived that he was wounded, till he was joined by some of the staff,

who observed the blood trickling down his thigh.

Even during the interval from the time of his being wounded, and the last

charge of cavalry, he walked with a firm and steady step along the line of

the Highlanders and General Stuart’s brigade, to the position of the

guards in the centre of the line, where, from its elevated situation, be

had a full view of the whole field of battle. Here he remained, regardless

of the wound, giving his orders so much in his usual manner, that the

officers who came to receive them perceived nothing that indicated either

pain or anxiety. These officers afterwards could not sufficiently express

their astonishment, when they came to learn the state in which he was, and

the pain which he must have suffered from the nature of his wound. A

musket ball had entered his groin, and lodged deep in the hip joint; the

ball was even so firmly fixed in the hip joint that it required

considerable force to extract it after his death. My respectable friend,

Dr. Alexander Robertson, the surgeon who attended him, assured me that

nothing could exceed his surprise and admiration at the calmness of his

heroic patient. With a wound in such a part, connected with and bearing on

every part of his body, it is a matter of surprise how he could move at

all, and nothing but the most intense interest in the fate of his army,

the issue of the battle, and the honour of the British name, could have

inspired and sustained such resolution. As soon as the impulse ceased in

the assurance of victory, he yielded to exhausted nature, acknowledged

that he required some rest, and lay down on a little sand hill close to

the battery."

From the field of victory he was removed on a litter, feeble and faint, on

board the admiral’s flag ship, ‘the Foudroyant,’ where every effort was

made by the medical gentlemen of the fleet and the army to extract the

ball, but without effect. During a week that he lingered in great bodily

suffering, he continued to exercise the same vigilance over the condition

and prospects of his army as he had manifested while at its head. His son,

Lieutenant-colonel Abercromby, attended him from day to day, and regularly

received his instructions, as if no serious accident had befallen him.

Throughout the evening of the 27th; he became more than usually restless,

and complained of excessive languor, and an increased degree of thirst;

next day mortification supervened, and in the evening he expired; thus

closing his glorious career, on the 28th March 1801, in the 68th year of

his age.

In the despatches sent home with an account of his death by General

(afterwards Lord) Hutchinson, who succeeded him in the command, the latter

says: "We have sustained an irreparable loss in the person of our

never-sufficiently-to-be-lamented commander-in-chief, Sir Ralph

Abercromby, who was mortally wounded in the action, and died on the 28th

of March. I believe he was wounded early, but he concealed his situation

from those about him, and continued in the field giving his orders with

that coolness and perspicuity which had ever marked his character, till

long after the action was over, when he fainted through weakness and loss

of blood. Were it permitted for a soldier to regret any one who has fallen

in the service of his country, I might be excused for lamenting him more

than any other person; but it is some consolation to those who tenderly

loved him, that, as his life was honourable, so was his death glorious.

His memory will be recorded in the annals of his country, will be sacred

to every British soldier, and embalmed in the recollection of a grateful

posterity." His remains were conveyed, (in compliance with his own

request,) to Malta, and interred in the Commandery of the Grand Master,

beneath the castle of St. Elmo. A monument was erected to his memory in

St. Paul’s Cathedral, parliament having voted a sum of money for the

purpose. His widow was created Baroness Abercromby of Aboukir and

Tullibody, with remainder to the heirs-male of the deceased general; and,

in support of the dignity, a pension of £2,000 a-year was granted to her,

and to the two next succeeding heirs-male.

Sir Ralph Abercromby possessed, in a high degree, some of the best

qualities of a general, and his coolness, decision, and intrepidity, were

the theme of general praise. As a country gentleman, also, his character

stood very high, being described as "the friend of the destitute poor, the

patron of useful knowledge, and the promoter of education among the

meanest of his cottagers." His studies were of so general a nature that it

is stated in Stirling’s edition of Nimmo’s History of Stirlingshire, that

when called to the continent in 1793, he had been daily attending the

lectures of the late Dr. Hardy, regius professor of church history in the

university of Edinburgh.

To Sir Ralph’s patronage many who would otherwise. have passed their.

lives in obscurity, owed their being placed in situations where they had

opportunities of advancement and distinction; among the rest was the late

Major-general Sir William Morison, K.C.B., one of the many able officers

whom the East India Company’s service has produced. His father, Mr.

Morison of Greenfield, Clackmannanshire, was a land surveyor in Alloa in

the county of Stirling, who was well known to most of the gentlemen in

that neighbourhood, and was in particular employed by Sir Ralph

Abercromby. When Sir Ralph was going abroad on foreign service, he had

occasion to consult Mr. Morison, the father, about one of his farms, and

was particularly pleased with the accuracy and clearness of the plan and

its references, which he submitted to him. On being asked who drew them

up, Mr. Morison told Sir Ralph that it was done by his son, and the

general immediately said that he should like to have the whole of his

estate mapped in the same manner, so that, when away from home, he might

be able, by reference, to correspond about any point that occurred. The

maps were made by young Morison, who waited on Sir Ralph to explain them,

and the veteran general, who was a great judge of character, instantly

perceived the value of the self-taught youth. He made inquiries as to his

views and prospects, and finding that he was anxious to go to India, he

procured for him a cadetship, in the year 1800. From the outset the young

man justified Sir Ralph’s estimate of his abilities, and he so applied his

faculties to military science, that his attainments raised him to a high

rank in the Indian army, and he died 15th May 1851, a major-general in the

East India Company’s service, a knight commander of the Bath, and member

of parliament for Clackmannanshire and Kinross-shire.

Sir Ralph married Mary Anne, daughter of John Menzies, Esq. of Ferntower,

Perthshire, and left four sons, viz. George, passed advocate in 1794, who

succeeded his mother on her death in 1821, as Lord Abercromby, and died in

1843; Sir John, a major-general, and G.C.B., who died unmarried in 1817;

James, a barrister at law, returned, with Francis Jeffrey, Esq.,

(subsequently a lord of session,) as one of the members of parliament for

the city of Edinburgh at the first election under the Reform act,

afterwards Speaker of the House of Commons, created Lord Dunfermline in

1839; and Alexander, a colonel in the army; with three daughters; Anne,

married to Donald Cameron, Esq. of Lochiel; Mary, died unmarried in 1825;

and Catherine, wife of Thomas Buchanan, Esq., in the East India Company’s

service. Lord Dunfermline, the third son, died in 1858, leaving a son,

Ralph, second Lord Dunfermline. (See DUNFERMLINE, Lord, vol. ii. p. 105.)

ABERCROMBY, ALEXANDER,

an eminent lawyer and occasional essayist, was born October 15, 1745. He

was the second son of George Abercromby of Tullibody, and the brother of

Sir Ralph. He received his education at the university of Edinburgh, and

was admitted a member of the faculty of advocates in 1766. He

distinguished himself at the bar, and in 1780, after being sheriff of

Stirlingshire, he became one of the depute-advocates. He was raised to the

bench in May 1792, when he assumed the title of Lord Abercromby; In

December of the same year, he was made a lord of justiciary. He was one of

the originators of the ‘Mirror,’ a periodical published at Edinburgh in

1779 and following year, to which he contributed eleven papers. He also

furnished nine papers to the ‘Lounger,’ a work of a similar kind,

published in 1785 and 1786. He caught a cold, while attending his duty on

the northern circuit in the spring of 1795, from which he never recovered,

and died on the 17th of November of that year, at Exmouth, in Devonshire,

where he had gone on account of his health. A short tribute to his memory

was written by his friend, Henry Mackenzie, for the Royal Society of

Edinburgh.—Haig and Brunton’s Senators of the college of Justice.

ABERCROMBY, SIR ROBERT,

the youngest brother of Sir Ralph Abercromby, was a general in the army, a

knight of the Bath, and at one period the governor of Bombay and

commander-in-chief of the forces in India. He was afterwards for thirty

years governor of the castle of Edinburgh. When the late Mr. Robert

Haldane, the brother of Mr. James Alexander Haldane, determined upon

selling his estates, and devoting himself to the diffusion of the gospel

in India, Sir Robert Abercromby, whose niece Mr. J, A. Haldane had

married, purchased from him his beautiful and romantic estate of Airthrey,

in Stirlingshire, and was succeeded by his nephew, Lord Abercromby, the

son of his elder brother, Sir Ralph. Sir Robert died in 1827.

Entries for this name in the Dictionary of

National Biography |