|

ERSKINE,

anciently spelled Areskin, and sometimes Irskyn, a surname of great

antiquity, and one which has been much distinguished in all periods of

Scottish history, was originally derived from the lands and barony of

Erskine in Renfrewshire, situated on the south side of the Clyde, the most

ancient possession of the noble family who afterwards became Lords Erskine

and earls of Mar.

An absurd

tradition asserts that at the battle of Murthill fought with the Danes, in

the reign of Malcolm the Second, a Scotsman having killed Enrique, a

Danish chief, cut off his head, and with the bloody dagger in his hand,

showed it to the king, saying in Gaelic, Eris Skene, alluding to

the head and dagger; on which Malcolm gave him the name of Erskine. In

those remote times, however, surnames were usually assumed from lands, and

all such traditions referring to the origin of the names of illustrious

families are seldom to be depended upon. The appearance of the land

justifies the derivation of the name from the British word ir-isgyn,

signifying the green rising ground. The earliest notice of the name is

in a confirmation of the church of “Irschen” granted by the bishop of

Glasgow in favour of the monastery of Paisley, betwixt the years 1202 and

1207 [Chartulary of Paisley, p. 113.] In 1703, the estate of

Erskine was purchased from the Hamiltons of Orbinston by Walter, master of

Blantyre, afterwards Lord Blantyre, in which family the property remains.

Henry de Erskine

was proprietor of the barony of Erskine so early as the reign of Alexander

the Second. He was witness of a grant by Amelick, brother of Maldwin, earl

of Lennox, of the patronage and tithes of the parish church of Roseneath

to the abbey of Paisley in 1226.

His grandson,

‘Johan de Irskyn,’ submitted to Edward the First in 1296.

Johan’s son, Sir

John de Erskine, had a son, Sir William, and three daughters, of whom the

eldest, Mary, was married, first to Sir Thomas Bruce, brother of King

Robert the First, who was taken prisoner and put to death by the English,

and secondly to Sir Ingram Morville; and the second, Alice, became the

wife of Walter, high steward of Scotland.

Sir William de

Erskine, the son, was a faithful adherent of Robert the Bruce, and

accompanied the earl of Moray and Sir James Douglas in their expedition

into England in 1322. For his valour he was knighted under the royal

banner in the field. He died in 1329.

Sir Robert de

Erskine, knight, his eldest son, made an illustrious figure in his time,

and for his patriotic services, was, by David the Second, appointed

constable, keeper, and captain of Stirling castle. He was one of the

ambassadors to England, to treat for the ransom of that monarch, after his

capture in the battle of Durham in 1346. IN 1350 he was appointed by

David, while still a prisoner, great chamberlain of Scotland, and in 1357

he was one of those who accomplished his sovereign’s deliverance, on which

occasion his eldest son, Thomas, was one of the hostages for the payment

of the king’s ransom. On his restoration, David, in addition to his former

high office of chamberlain, appointed Sir Robert Justiciary north of the

Forth, and constable and keeper of the castles of Edinburgh and Dumbarton.

In 1358 he was ambassador to France, and between 1360 and 1366 he was five

times ambassador to England. In 1367 he was warden of the marches, and

heritable sheriff of Stirlingshire. In 1371 he was one of the great barons

who ratified the succession to the crown of Robert the Second, grandson,

by his daughter Marjory, of Robert the Bruce, and the first of the Stuart

family. To his other property he added that of Alloa, which the king

bestowed on him, in exchange for the hunting district of Strathgartney, in

the Highlands. He died in 1385.

His son, Sir

Thomas Erskine, knight, succeeded his father, as governor of Stirling

castle, and in 1392 was sent ambassador to England. By his marriage with

Janet Keith, great-grand-daughter of Gratney, eleventh earl of Mar, he

laid the foundation of the succession on the part of his descendants to

the earldom of Mar and lordship of Garioch.

Sir Robert

Erskine, knight, his son, was one of the hostages for the ransom of James

the First in 1424. On the death of Alexander, earl of Mar, in 1435, he

claimed that title in right of his mother, and assumed the title of earl

of Mar, but the king unjustly kept him out of possession. He died in 1453.

Sir Thomas

Erskine, his son, was dispossessed of the earldom of Mar by an assize of

error, in 1457, but in 1467 he was created a peer under the title of Lord

Erskine.

This family were

honoured for several generations with the duty of keeping, during their

minority, the heirs apparent to the crown.

Alexander, the

second Lord Erskine, had the charge of James the Fourth, when prince of

Scotland, and ever after continued in high favour with him. He died in

1510.

John, the fourth

Lord Erskine, had the keeping of James the Fifth during his minority. On

his coming of age he was sent by James in 1534 ambassador to France, to

negociate a marriage with a daughter of the French king, and afterwards he

was sent ambassador to England. On the death of James, in conjunction with

Lord Livingston, he had committed to him the charge of the infant queen

Mary. He dept her for some time in Stirling castle, and afterwards removed

her to the priory of Inchmahome, situated on an island in the lake of

Monteith, in Perthshire; which priory had been bestowed upon him by James

the Fifth, as commendatory abbot. Subsequently, for greater security, he

conducted the youthful Mary to France. He died in 1552. Margaret Erskine,

daughter of this nobleman, was the mother, by James the Fifth, of the

regent Murray.

His eldest son,

the master of Erskine, was killed at the battle of Pinkie in 1547. He was

the ancestor, by an illegitimate son, of the Erskines of Shielfield, near

Dryburgh, of which family the famous Ebenezer and Ralph Erskine, the

originators of the first secession from the Church of Scotland, were

cadets. Memoirs of them are given below. The fourth son, the Hon. Sir

Alexander Erskine of Gogar, was the ancestor of the earls of Kellie. [See

KELLIE, earl of.]

The second son,

John, the fifth Lord Erskine, succeeded his father as governor of

Edinburgh castle. Although a Protestant himself, he preserved a strict

neutrality in the struggles between the Lords of the Congregation and the

queen regent, Mary of Guise, while he upheld the authority of the latter,

to whom, when hard pressed by her enemies, he gave protection in the

castle of Edinburgh, where she died in June 1560. On the return of Queen

Mary from France in 1561 he was appointed one of her privy council. In the

following year he submitted his claim to the earldom of Mar to parliament,

and was successful in establishing his right as the descendant, in the

female line, from Gratney, eleventh earl of Mar. [See MAR, earl of.] In

consequence of Lord Erskine being confirmed earl of Mar, the queen’s

natural brother, afterwards regent, who then bore the title, was styled

earl of Moray instead. On the birth of James the Sixth in 1566, the new

earl of Mar was intrusted with the keeping of the young prince; and on the

death of the earl of Lennox in 1571 he was chosen regent in his stead. He

died in the following year, leaving a high reputation for integrity and

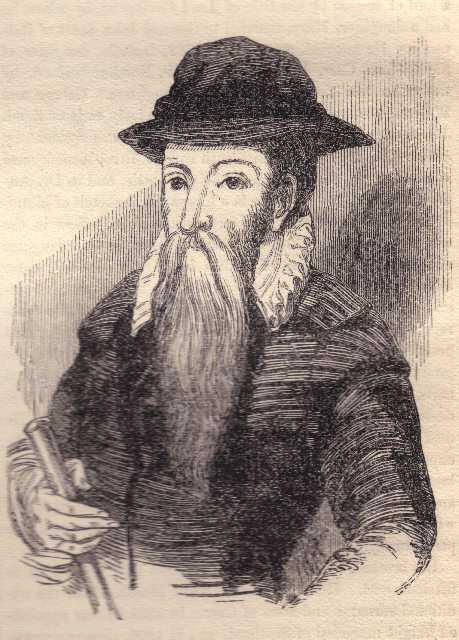

honesty of purpose. From a portrait of the regent Mar in Pinkerton’s

Scottish Gallery, the subjoined woodcut is taken:

[portrait of John Lord Erskine]

The first of the family of Erskine, barons of Dun, as separated from that

of Erskine of Erskine, the original stock, was John the son of Sir Thomas

Erskine of that ilk, who had a charter from King Robert the Second of the

barony of Dun, near the town of Montrose, in Forfarshire, dated November

8, 1376. The name of Dun is Gaelic, and signifies a hill or rising ground.

This Sir Thomas was twice married; first to Janet Keith, by whom he had

Sir Robert Erskine, and a daughter, married to Duncan Weems, younger of

Lochar Weems; and secondly, to Jean Barclay, by whom he had John Erskine,

already mentioned, who succeeded to the lands of Dun, as appears by a

charter to him, from King Robert the Third, of these lands, dated October

25, 1393.

The next in succession in the lands of Dun was Alexander Erskine, supposed

to be the son of John. He resigned the lands of Dun, reserving his own

liferent, to his son, John the second, who received from King James the

Second a charter to the same, of date January 28, 1449. The vesting the

fee of the property in the eldest son, while the father retained the

liferent, became afterwards a practice in the family.

John Erskine of Dun, the second of that name, had three sons: John, his

heir, Thomas, and Alexander. He resigned his lands of Dun to his eldest

son in 1473, retaining the liferent, and died March 15, 1508.

John Erskine of Dun, the third of that name, had several sons, of whom

Thomas Erskine of Brechin, the second son, was secretary to King James the

Fifth. He fell on the fatal field of Flodden, September 9, 1513. This John

Erskine, laird of Dun, treated the inhabitants of Montrose in the most

tyrannical manner, and in consequence of his oppressive conduct and that

of his family the town applied to the king for redress. A summons of

spulzie was accordingly issued against him and four of his sons, 4th

October, 1493.

Sir John Erskine, the fourth of that name, married Margaret Ruthven,

daughter of William first Lord Ruthven, widow of the earl of Buchan, by

whom he had John Erskine of Dun, knight, one of the principal leaders of

the Reformation in Scotland, and afterwards superintendent of Angus, of

whom a memoir is afterwards given below.

A

succeeding proprietor of Dun, John by name, was poisoned on the 23d May,

1613, by his uncle Robert. The trial of the latter, as well as that of his

three sisters, by whom he was instigated to the atrocious deed, will be

found in Pitcairn’s Criminal Trials, vol. iii. pp. 261-266.

Of

the later lairds of Dun the only other personage of public note was David

Erskine, Lord Dun, a judge of the court of session, of whom also a notice

is afterwards given.

The estate of Dun came into possession of the noble family of Kennedy, by

the marriage, on June 1, 1793, of Archibald, 12th earl of

Cassillis, and first marquis of Ailsa, with Margaret, 2d daughter of John

Erskine, Esq. of Dun. Their 2d son, John, born June 4, 1802, on inheriting

the property, assumed the additional surname of Erskine. He married, in

1827, Lady Augusta Fitzclarence, 4th daughter of William IV.,

and died at Pisa, March 6, 1831. His widow married again, in 1836, Lord

John Frederick Gordon Hallyburton of Pitcur, 3d son of 9th

marquis of Huntly. Mr. Kennedy Erskine, with two daughters, left one son,

William Henry, born July 1, 1828, at one time a captain 17th

lancers, unmarried. The elder daughter, Wilhelmina, married, in 1855, her

cousin, 2d earl of Munster; the younger, Millicent Ann Mary, became the

wife of J. Hay Wemyss, Esq. of Wemyss Castle, Fifeshire.

Alexander Erskine, plenipotentiary for Sweden at the treaty of Munster, a

distinguished officer in the army of Gustavus Adolphus, was of the family

of Erskine of Kirkbuddo in Fife, sprung from the Erskines of Dun. Ennobled

in Sweden, some of his descendants were settled at Bonne in Germany.

_____

The Erskines of Alva (represented by the earl of Rosslyn) are sprung from

a branch of the noble house of Mar, descended from Hon. Charles Erskine, 5th

son of John, 7th earl of Mar. His eldest son, Charles Erskine

of Alva, was created a baronet of Nova Scotia, 30th April 1666.

Sir Charles had four sons and one daughter. Charles, Lord Tinwald, his

third son, a lord of session, and afterwards lord justice clerk, was

father of James Erskine, Lord Alva, also a lord of session.

The grandson of the first baronet, Lieutenant-general Sir Henry Erskine,

distinguished himself as a minor song writer. The second son of Sir John

Erskine of Alva, second baronet, he succeeded to the baronetcy, on the

death of his elder brother, in 1747. He was for many years M.P. for the

Anstruther district of burghs. He early entered the army, but in 1756 he

lost his rank, on account of his opposition to the importation of the

Hanoverian and Hessian troops into this country. After the accession of

George III. in November 1760, he was restored to his rank in the army, and

appointed colonel of 67th foot. He married at Edinburgh, in

1761, Janet, only daughter of Peter Wedderburn, Esq. of Wedderburn, a lord

of session, under the name of Lord Chesterhall. Sir Henry was deputy

quarter-master-general, and succeeded his uncle, Hon. General St. Clair,

in the command of the Royal Scots in 1762. He was the author of the song,

‘In the garb of old Gaul,’ the air of which was composed by the late

General Reid. He died at York, 9th August 1765. His eldest son,

Sir James Erskine, also in the army, assumed the surname of St. Clair, and

on the death of his uncle, Alexander Wedderburn, earl of Rosslyn, in 1805,

became 2d earl of Rosslyn, and died 8th June 1837. (Electric

Scotland Note: We got in an email from Toni saying that this date is

incorrect and gave us

January

18th, 1837 as the correct date.) [See ROSSLYN,

earl of.]

_____

There is also the family of Erskine of Cambo in Fife, on which a baronetcy

was conferred in 1821. Sir David, the first baronet, was the grandson of

the tenth earl of Kellie. He died in 1841. His son, Sir Thomas, the 2d

baronet, born in 1824, is an officer in the army, and married, with issue.

ERSKINE,

JOHN,

of Dun, knight, one of the principal promoters of the Reformation in

Scotland, was born in 1508, at the family seat of Dun, near Montrose. His

grandfather, father, uncle and granduncle, fell at Flodden, and he

succeeded to the estate of Dun when scarcely five years old. By the care

of his uncle, Sir Thomas Erskine of Brechin, secretary to King James the

Fifth, he received a liberal education; but had scarcely attained to the

years of majority, when he appears to have killed Sir William Forster, a

priest of Montrose. The document which preserves the record of this fact,

and of the assythment or manbote paid by him to the father of the

deceased, dated 5th February 1530, is inserted among the Dun

papers in the Miscellany of the Spalding Club, vol. fourth. None of the

circumstances are given, except that the deed was committed in the Bell

Tower of Montrose. He studied at a foreign university, and he has the

merit of being the first to encourage the acquisition of the Greek

language in Scotland, having, in 1534, on his return from abroad, brought

with him a Frenchman capable of teaching it, whom he established in

Montrose. He seems about this time to have married Lady Elizabeth Lindsay,

daughter of the earl of Crawford. This lady died 29th July

1538, and he subsequently married Barbara de Beirle.

On

the 10th of May, 1537, he had a license from James V. for

himself, his son John, and other relatives, permitting them “to pas to the

partis of France, Italie, or any uthiris beyond se, and thair remane, for

doing of thair pilgramagis, besynes, and uthir lefull erandis, for the

space of thre yeiris.” His uncle, Sir Thomas Erskine of Brechin, had

obtained from the same monarch a gift of the office of constabulary of

Montrose, which he conveyed by a charter, dated 9th February

1541, to John Erskine of Dun, the subject of this notice, in liferent, and

to his son and heir apparent, John Erskine, in fee. In April 1542 he and

his cousin, Thomas Erskine of Brechin, and John Lambie of Duncarry, had a

license to travel into France, Italy, and other places, for two years. [Dun

Papers in Spalding Club Miscellany, vol. 4.]

Having early become a convert to the Reformed doctrines, he was a zealous

and liberal encourager of the Protestants, especially of those who were

persecuted, to whom his house of Dun was always a sanctuary, as he was a

man of too much power and influence for the popish bishops to interfere

with. In his endeavours, however, to promote the Reformation, he did not

neglect his other duties. During the years 1548 and 1549 he supported the

queen dowager and the French party in opposing the English forces, and we

learn from the histories of the time that in 1548, some English ships

having landed about eighty men in the neighbourhood of Montrose, for the

purposes of plunder, Erskine of Dun collected a small force from the

inhabitants of that town, of which he was then provost, and had for some

years been constable, and fell upon them with such fury, that not a third

of them regained their ships. Among the Dun papers which have been

published, are several letters to the laird of Dun from Mary, the queen

dowager. These refer to the passing events of the period, and show the

high estimation in which he was held by her. One of them, dated 29th

August, 1549, relates to the coming to Montrose of the French Captain

Beauschattel, and his company, regarding which Erskine seems to have

remonstrated, dreading some attempts against his rights, as her majesty

assures him that there was “na entent bot till kepe the fort, and nocht

till hurt you in your heretage or ony othir thing.” It appears that a

small hill, close to the river, was called the Fort, or Constable Hill [Bowick’s

Life of Erskine, page 62, quoted in the Spalding Club Miscellany,

vol. 4, preface, page xii, note], and it has been

conjectured that Erskine may have thought the occupation of this fort by

the French captain derogatory to his rights as constable, and so made it

subject of complaint. He was considered not only by his own countrymen,

but by foreigners, as one of the most eminent heroes which the Scottish

nation had produced in that age, so fertile in great men, and M. Beauge,

in his History of the Campaigns in Scotland of 1548 and 1549, makes

frequent and honourable mention of him and his exploits at that time.

At

Stirling, March 10, 1556, the laird of Dun and some others, signed a

“call” to John Knox, then at Geneva, to return to Scotland, and promote

the Reformation. On Knox’s arrival, that year, Erskine, being in

Edinburgh, was one of those who used to meet in private houses to hear him

preach. It was at supper in the laird of Dun’s house, that all present

there with Knox resolved, that, whatever might be the consequence, they

would wholly discontinue their attendance at Mass. On his invitation, the

Reformer followed him to Dun, where, on this, as well as on a subsequent

visit, he preached almost daily, and made many converts. On the 3d

December 1557 Erskine of Dun subscribed the first Covenant at Edinburgh,

along with the earls of Argyle and Glencairn, and other noblemen and

gentlemen, and thus became one of the lords of the congregation.

In

the parliament which met December 14, 1557, he was appointed, under the

title of ‘john Erskine of Dun, knight, and provost of Montrose,” to go to

the court of France, as one of the commissioners, to witness the young

Queen Mary’s marriage with the dauphin. “Of which trust he acquitted

himself with great fidelity and honour, and was approved by the parliament

on his return.” On his return, he found the Reformation making great

progress in Scotland; and when the Protestants, encouraged by their

increase of numbers, and the accession of Queen Elizabeth to the English

throne, petitioned the queen regent, more boldly than formerly, to be

allowed the free exercise of their religion, the laird of Dun was one of

those who joined in the prayer, but he seems to have used milder language,

and been more moderate in his demands than the others. So far, however,

from granting the toleration requested, the queen regent issued a

proclamation requiring the Protestant ministers to appear at Stirling on

May 10, 1559, to be tried as heretics and schismatics. The lords of the

congregation, and other favourers of the Reformation, seeing the danger to

which their preachers were exposed, resolved to accompany and protect

them. Anxious to avoid bloodshed, Erskine of Dun left his party at Perth,

and, with their consent, went forward to Stirling, to have a conference

with the queen, who acceded to his advice, and agreed that the ministers

should not be tried. He accordingly wrote to those who were assembled at

Perth to stay where they were, as the queen regent had consented to their

wishes. But while many of the people dispersed on receiving this

intelligence, the barons and gentlemen, rightly distrusting the regent’s

word, resolved to remain in arms till after the 10th of May.

And well was it that they did so, for the queen had no sooner made the

promise than she perfidiously broke it. The preachers not appearing on the

day named, were denounced rebels, which so incensed and disgusted the

laird of Dun that he withdrew from court, and joined the lords of the

congregation at Perth, when he explained to them that in giving his advice

to disperse he had himself been deceived by the regent. He therefore

recommended them to provide against the worst, as they might expect no

favour, and a civil war ensued, which lasted for some time, and ended at

last, first in the deposition, October 23, 1559, and secondly on the death

of the queen regent, June 10, 1560, in favour of the Protestants.

The laird of Dun, previous to that event, had relinquished his armour, and

become a preacher, for which he was, from his studies and disposition,

peculiarly qualified. In the ensuing parliament, he was nominated one of

the five ministers who were appointed to act as ecclesiastical

superintendents, the district allotted to him being the counties of Angus

and Mearns. This appointment took place in July 1560, and he was installed

in 1562 by John Knox. The superintendents were elected for life, and

though their authority was somewhat similar to that of a bishop, they were

responsible for their conduct to the General Assembly. The other four

superintendents were, Mr. John Spottiswood of Spottiswood, the father of

Archbishop Spottiswood, of Lothian; John Willocks, formerly a Dominican

friar, of Glasgow; John Winram, formerly subprior of St. Andrews, of Fife;

and John Carsewell, of Argyle and the Isles. The laird of Dun not only

superintended the proceedings of the inferior clergy, but performed

himself the duties of a clergyman. He was appointed moderator of the ninth

General Assembly at Edinburgh, December 25, 1564; also of the eleventh the

same day and place, 1565; also of the twelfth at Edinburgh, June 25, 1566;

and of the thirteenth at Edinburgh, December 25, 1566. In January 1572 he

attended the convention held at Leith, where episcopacy was established.

His gentleness of disposition recommended him to Queen Mary, who, on being

requested to hear some of the Protestant preachers, answered, as Knox

relates, “That above all others she would gladly hear the superintendent

of Angus, Sir John Erskine, for he was a mild and sweet-natured man, and

of true honesty and uprightness.”

In

1569, by virtue of a special commission from the Assembly, he held a

visitation of the university of Aberdeen, and suspended from their

offices, for their adherence to popery, the principal, sub-principal, and

three regents or professors of King’s college, Aberdeen. In 1571 he showed

his zeal for the liberties of the church, in two letters which he wrote to

his chief, the regent earl of Mar, the first of which will be found in

Calderwood, vol. 3. They are written, says Dr. M’Crie, “in a clear,

spirited, and forcible style, contain an accurate statement of the

essential distinction between civil and ecclesiastical jurisdiction, and

should be read by all who wish to know the early sentiments of the Church

of Scotland on this subject.” In 1577 he assisted in compiling the ‘Second

Book of Discipline.’ Besides the duties belonging to his spiritual charge,

he was frequently called upon to execute those belonging to his military

character as a knight; thus, on the 20th of September 1579, he

was required, by a warrant from the king, to recover the house of

Redcastle from James Gray, son of Patrick Lord Gray, and his accomplices,

by whom it had been seized and retained, and deliver it to John Stewart,

the brother of the Lord Innermeith. Notwithstanding that the reformation

had, in his day, made so great progress in Scotland, and that he himself

had been one of the principal promoters of it, he was it seems not

altogether divested of some of the superstitious observances of popery. In

the ‘Spalding Miscellany,’ vol. iv. mention is made of a license from the

king, signed James R., with consent of his privy council, of date February

25, 1584, to John Erskine of Dun, to eat flesh all the time of Lent, and

as oft as he pleases on the forbidden days of the week, to wit, Wednesday,

Friday, and Saturday; noted upon the back, with the same hand, a license

to your L— to eat flesh; he being then past the age of seventy-six. In

1580, four years before this, he had received a license, wherein he, and

three in company with h im, are allowed to eat flesh from February 13 to

March 26.

From the laird of Dun’s conciliatory disposition, as well as his high

intelligence, his advice and assistance were valued by all parties, as

appears by various letters in the ‘Spalding Miscellany,’ vol. iv. Perhaps

one of the most important of these, in its bearing on the church, is one

addressed to him by the earl of Montrose and the secretary Maitland on 18th

November 1584, which seems to have been written with the view of obtaining

Erskine’s assent to certain statutes, then recently passed in parliament,

at the king’s instance, declaring his supremacy in all ecclesiastical

matters, which were obnoxious to the leading clergy of the time. The

ministers were required to subscribe an “obligation,” recognising his

majesty’s supremacy, under pain of deprivation of their benefices; and the

proceedings which ensued on the proclamation for the fulfilment of these

enactments are minutely detailed in ‘Calderwood’s Church History,’ vol.

iv. page 209, et seq.

In

consequence of the part taken by Erskine in prevailing on the ministers

within his bounds to subscribe “the obligation,” he acquired some

unpopularity among them; in the expressive words of Calderwood, “the laird

of Dun was a pest then to the ministers in the north.” A letter from

Patrick Adamson, titular archbishop of St. Andrews, to Erskine, dated 22d

January 1585, inserted among the Dun papers in the ‘Spalding Miscellany,’

seems intended to give explanations about “the obligation,” as he says

“the desyr of his Maiesties obligatioun extrendis no forthir bot to his

hienes obedience, and of sik as bearis charge be lawfull commission in the

cuntrie, quheirof his Maiestle hes maid ane speciall chose of your

lordship: as for the diocese of Dunkeld, I think your lordship will

understand his Maiesties meining at your cuming to Edinbrught, and as ffor

sik pairtis as is of the diocese of Sanct Androwis in the Merns and Anguse,

I pray your lordship to tak ordour thairin for thair obedience and

conformitie, as your lordship hes done befoir, that they be nocht

compellit to travell forthir, bot thair suspendis may be rathir helpit nor

hinderit;” with more to the same purpose. It appears from a summons, at

the instance of the laird of Dun, for payment of his stipend as

superintendent of Angus and Mearns, dated 9th September 1585,

that the whole amount of it in money and victual, did not much exceed

£800. The portion paid in money was £337 11s. 6d. [Miscellany of

Spalding Club, vol. iv, Editor’s preface.] He died March 12,

1591, in the 82d year of his age. Buchanan, Knox, Spottiswood, and others,

unite in speaking highly of his learning, piety, moderation, and great

zeal for the Protestant religion. Spottiswood says of him that he governed

that portion of the country committed to his “superintendence with great

authority, bill his death, giving no way to the novations introduced, nor

suffering them to take place within the bounds of his charge, while he

lived. A baron he was of good rank, wise, learned, liberal, and of

singular courage; who, for diverse resemblances, may well be said to have

been another Ambrose. He left behind him a numerous posterity, and of

himself and of his virtues a memory that shall never be forgotten.” –

Miscellany of the Spalding Club. – Scott’s Lives of Reformers. – M’Crie’s

Lives of Knox and Melville. – Calderwood’s History.

ERSKINE,

DAVID, LORD DUN,

an eminent lawyer, of the same family as the superintendent, was born at

Dun, in Forfarshire, in 1670. From the university of St. Andrews he

removed to that of Paris, and having completed the study of general

jurisprudence, he returned to Scotland, and was, in 1696, admitted

advocate. He was the staunch friend of the nonjurant episcopal clergy, and

in the last Scottish parliament zealously opposed the Union. In 1711 he

was appointed one of the judges of the court of session, and in 1713 one

of the lords of justiciary. In 1750 his age and infirmities induced him to

retire from the bench. In 1754 he published a small volume of moral and

political ‘Advices,’ which bears his name. He died in 1755, aged 85. By

his wife, Magdalen Riddel, of the family of Riddel of Haining in

Selkirkshire, he left a son, John, who succeeded him in the estate of Dun,

and a daughter, Anne, married first to James, Lord Ogilvy, son of David,

third earl of Airly, and secondly to Sir James Macdonald of Sleat. –

Scots Mag. 1754.

ERSKINE,

HENRY, REV.,

a divine of considerable eminence, the ninth of twelve children, – not

thirty-three, as has been generally stated, – of Ralph Erskine of

Shielfield, in Berwickshire, descended from the noble house of Mar, was

born at Dryburgh, Berwickshire, in 1624. He studied at the university of

Edinburgh, where he took the degree of M.A., and was soon after licensed

to preach the gospel. In 1649 – as stated by Wodrow, but according to Dr.

Harper, in his Life of Ebenezer Erskine, more probably ten years later,

viz. in 1659, as stated by Calamy and Palmer – he was, by the English

Presbyterians, ordained minister of Cornhill, in the county of

Northumberland, where he continued till he was ejected by the act of

Uniformity, August 24, 1662. He was thus minister of Cornhill for three

years. [Calamy’s Continuation, Palmer’s Noncon. Memorial.] He now

removed with his family to Dryburgh, where he appears to have resided for

eighteen years, and where he occasionally exercised his sacred office. In

the severe persecution to which the Presbyterians in Scotland were at that

period subjected, this faithful minister could not of course expect to

escape; and, accordingly, on Sabbath, April 23, 1682, a party of soldiers

came to his house, and, seizing him while worshiping God with his family,

carried him to Melrose a prisoner. Next day he was released on bond for

his appearance when required, and soon after was summoned to appear before

the council at Edinburgh, to answer charges of sedition and disobedience,

because he presumed to exercise his ministry without conforming to the new

order of things. On his refusal to swear that he had not altogether

refrained from the duties of his ministry, and to “give bond that he would

preach no more at conventicles,” he was ordered to pay a fine of 5,000

merks, and committed to the Tolbooth of Edinburgh, to be afterwards sent

to the prison of the Bass till the fine was paid; but, on petition, he

obtained a remission of his sentence on condition of leaving the kingdom.

One account states, that he took refuge in Holland, whence the want of the

necessaries of life induced him to return to Scotland, when he was

imprisoned in the Bass for nearly three years, but this statement rests on

questionable authority. It is certain that he resided for some time at

Parkbridge, in Cumberland, and afterwards at Monilaws, about two miles

from Cornhill, in Northumberland, whence he had been ejected. On July 2,

1685, he was again apprehended, and kept in prison till the 22d, when he

was set at liberty, in terms of the act of Indemnity passed at the

commencement of the reign of James II. In September 1687, after the

toleration granted by King James’ proclamation of indulgence, Mr. Erskine

became minister of Whitsome, on the Scots side of the Border; and it was

under his ministry, at this place, that the celebrated Thomas Boston

received his first religious impressions. He remained at Whitsome till

after the Revolution, when he was appointed minister of Chirnside, in the

county of Berwick. He continued minister of that place till his death,

August 10, 1696, aged sixty-eight. He left several Latin manuscripts,

among others, a Compend of Theology, explanatory of some difficult

passages of Scripture, none of which were ever published. He was twice

married. His first wife, who died in 1670, was the mother of eight

children, one of whom, Philip, conformed to the Church of England, and,

receiving episcopal orders, held a rectory in the county of

Northumberland. Another child of the first marriage became afterwards

well-known as Mrs. Balderstone of Edinburgh, a woman of superior

intelligence and of devoted piety. By his second wife, Margaret Halcro, a

native of Orkney, a descendant of Halcro, prince of Denmark, and whose

great grandmother was the Lady Barbara Stuart, daughter of Robert, earl of

Orkney, son of James V., he was the father of Ebenezer and Ralph Erskine,

the founders of the Secession in Scotland.

The death of Mr. Henry Erskine took place in the midst of his family; and

the circumstances of it as related by Dr. Calamy [Continuation] are

peculiarly interesting, from the impression which they appear to have made

on the young hearts of his two celebrated sons, Ebenezer and Ralph. Long

after, remarks Dr. Harper, the scene was referred to by them as one of

their hallowed recollections. “The Lord helped me,” says Ebenezer on one

occasion, “to speak of his goodness, and to declare the riches of his

grace in some measure to my own soul. He made me tell how my father took

engagements of me on his deathbed, and did cast me upon the providence of

his God.” Ralph, in like manner, more than thirty years after the event,

put on record, “I took special notice of the Lord’s drawing out my heart

towards him at my father’s death.” – Memoir of Rev. H. Erskine. – Dr.

Harper’s Life of Ebenezer Erskine.

ERSKINE,

EBENEZER,

the founder of the Secession church in Scotland, fourth son of the

preceding, was born June 22, 1680. Some accounts say his birth-place was

the prison of the Bass, but this is evidently erroneous. His biographer,

the Rev. Dr. Fraser of Kennoway, thinks it probable that he was born at

the village of Dryburgh, in Berwickshire, and in confirmation of this the

Rev. Dr. Harper of Leith, in his Life of Ebenezer Erskine, gives the

following extract from a small manuscript volume belonging to Mr. Henry

Erskine, Ebenezer’s father, in possession of the Rev. Dr. Brown of

Broughton Place church, Edinburgh: “Eben-ezer was borne June 22d, being

Tuesday, at one o’clock in the morning, and was baptized by Mr. Gab:

Semple July 24th, being Saturnday, in my dwelling house in

Dryburgh 1680.” He appears to have received the elements of his education

at home, under the superintendence of his father, and in his fourteenth

year he was sent to the university of Edinburgh, where he held a bursary

on the presentation of Pringle of Torwoodlee, and where he prosecuted his

studies for a period of nine years, four of which were devoted to the

classics and philosophy, and five to theology. IN June 1697, he took his

degree of M.A., and on leaving college he became tutor and chaplain in the

family of the earl of Rothes. He was licensed to preach by the presbytery

of Kirkaldy on the 11th February 1703, and in the succeeding

September was ordained minister of Portmoak, Kinross-shire. It was not

till after his ordination that his heart appears to have received its

first powerful impressions of evangelical and vital religion, and a

corresponding change to the better of spirit and style took place in his

public ministrations. Exemplary in the discharge of his ministerial

duties, and devoted to his people, he soon became popular amongst them.

“Nor,” says Dr. Harper, “was Mr. Erskine’s popularity and usefulness

confined to Portmoak and its immediate vicinity. From all parts of the

country, in every direction, sometimes at the distance of sixty miles,

eager listeners flocked to his preaching. On sacramental occasions

particularly, the gatherings were great. From all accounts of the sacred

oratory of the man, there is no doubt that there was in it much to impress

a promiscuous audience. His bodily presence was commanding, – his voice

full and melodious, – his manner grave and majestic, – and after the

fulness and fervour of his heart broke through the trammels of his earlier

delivery, his bearing in the pulpit combined ease with dignity in an

unwonted degree. But to whatever extent these external advantages

commended him to the people, it is gratifying to remark the most

unequivocal proofs that the great charm – the element of power which

signalized Mr. Erskine as a preacher, – was the thoroughly evangelical

matter and spirit of his discourses.” [Life of Ebenezer Erskine by Dr.

Harper, pp. 10, 21.]

In

the various religious contests of the period he took an active part,

particularly in the famous Marrow controversy, which commenced in 1719,

and in which he came forward prominently in defence of the doctrines,

which had been condemned by the General Assembly, contained in the work

entitled ‘The Marrow of Modern Divinity.’ He revised and corrected the

Representation and Petition presented to the Assembly on the subject, May

11, 1721, which was originally composed by Mr. Boston; and drew up the

original draught of the answers to the twelve queries put to the twelve

brethren; along with whom he was, for their participation in this matter,

solemnly rebuked and admonished by the moderator. This took place in the

Assembly of 1722. The twelve representers submitted to the authority of

the supreme court, but accompanied their submission with a protest against

the deed, and their claim of liberty “to profess, preach, and still bear

testimony to the truths condemned.” In the cases, too, of Mr. Simson,

professor of divinity at Glasgow, and Mr. Campbell, professor of church

history at St. Andrews, who, though both had been proved to have taught

heretical and unscriptural doctrines, were very leniently dealt with by

the Assembly, as well as on the question of patronage, he distinguished

himself by his opposition to the proceedings of the church judicatories.

The high estimation in which Mr. Erskine was held procured him at

different times the honour of a call from Burntisland, Tulliallan,

Kirkcaldy, and Kinross, but the church courts, in full concurrence with

his own views and inclinations, decided against his removal in all these

cases, although party feeling, particularly as regards Kirkcaldy, had its

influence in preventing his translation. In May 1731 he accepted of a call

to the third charge, or West church, at Stirling, and, in September of

that year, he was settled one of the ministers of that town. Having always

opposed patronage, as contrary to the standards of the Church, and as a

violation of the treaty of Union, he was one of those who remonstrated

against the act of Assembly of 1732 regarding vacant parishes. As

moderator of the Synod of Perth and Stirling, he opened their meeting at

Perth, on October 10th of that year, with a sermon from Psalm

cxviii. 24, in which he expressed himself with great freedom against

several recent acts of the Assembly, and particularly against the rigorous

enforcement of the law of patronage, and boldly asserted and vindicated

the right of the people to the election of their minister. Several members

of Synod immediately complained of the sermon, and, on the motion of Mr.

Mercer of Aberdalgie, a committee was appointed to report as to some

“unbecoming and offensive expressions,” alleged to have been used by the

preacher on the occasion. Having heard Mr. Erskine in reply to the charges

contained in the report of the committee, the Synod, after a keen debate

of three days, by a majority of not more than six, “found that he was

censurable for some indecorous expressions in his sermon, tending to

disquiet the peace of the Church,” and appointed him to be rebuked and

admonished. From this decision twelve ministers and two elders dissented.

Mr. Erskine, on his part, protested and appealed to the next Assembly. To

his protest, Messrs. William Wilson of Perth, Alexander Moncrieff of

Abernethy, and James Fisher of Kinclaven, ministers, adhered.

The Assembly, which met in May 1733, refused to hear the reasons of

protest, but took up the cause as it stood between Mr. Erskine and the

Synod; and, after hearing parties, “found the expressions vented by him,

and contained in the minutes of Synod, and his answers thereto, to be

offensive, and to tend to disturb the peace and good order of the Church;

and therefore approved of the proceedings of the Synod, and appointed him

to be rebuked and admonished by the moderator at their bar, in order to

terminate the process.” Against this decision Mr. Erskine lodged a

protest, vindicating his claim to the liberty of testifying against the

corruptions and defections of the Church upon all proper occasions. To

this claim and protestation the three ministers above named adhered, and

along with Mr. Erskine, withdrew from the court. On citation they appeared

next day, when a committee was appointed to confer with them; but,

adhering to their protest, the farther proceedings were remitted to the

Commission, which met in the ensuing August, when Mr. Erskine and the

three ministers were suspended from the exercise of their office, and

cited to appear again before the Commission in November. At this meeting

the four brethren were, by the casting vote of the moderator, declared to

be no longer ministers of the Church of Scotland, and their relationship

with their congregations formally dissolved. When the sentence of the

Commission was intimated to them, they laid on the table a paper declaring

a secession from the prevailing party in the established church, and

asserting their liberty to exercise the office of the Christian ministry,

notwithstanding their being declared no longer ministers of the Church of

Scotland.

On

the 5th day of the subsequent December, the four ejected

ministers met together at the Bridge of Gairney, near Kinross, and after

two days spend in prayer and pious conference, constituted themselves into

a presbytery, under the designation of the “Associate Presbytery.” Mr.

Erskine was elected the first moderator, and from this small beginning the

Secession Church took its rise.

The General Assembly of 1734, acting in a conciliatory spirit, rescinded

several of the more obnoxious acts, and authorised the Synod of Perth to

restore the four brethren to communion and to their respective charges,

which was done accordingly by the Synod, at its next meeting, on the 2d

July. The seceding ministers, however, refused to accept the boon, and

published their reasons for this refusal. On forming themselves into the

“Associate Presbytery,” they had published a ‘Testimony to the Doctrine,

Worship, and Discipline of the Church of Scotland.’ In December 1736 they

published a Second Testimony, in which they condemned what they considered

the leading defections of both Church and State since 1650. In February

1737 Mr. Ralph Erskine, minister of Dunfermline, brother to Ebenezer, and

Mr. Thomas Mair, minister of Orwell, joined the Associate Presbytery, and

soon after two other ministers also acceded to it.

In

the Assembly of 1739 the eight brethren were cited to appear, when they

gave in a paper called ‘The Declinature,’ in which they denied the

Assembly’s authority over them, or any of their members, and declared that

the church judicatories “were not lawful nor right constituted courts of

Jesus Christ.” In the Assembly of 1740 they were all formally deposed from

the office of the ministry. In that year, a meeting-house was built for

Mr. Erskine by his hearers at Stirling, where he continued to officiate to

a very numerous congregation till his death. During the rebellion of 1745,

Mr. Erskine’s ardent loyalty led him to take a very active part in support

of the government. Animated by his example the Seceders of Stirling took

arms, and were formed into a regiment for the defence of the town. Dr.

Fraser, his biographer, relates that one night when the rebels were

expected to make an attack on Stirling, Mr. Erskine presented himself in

the guardroom fully accoutred in the military garb of the times. Dr. John

Anderson, late professor of natural philosophy in the university of

Glasgow, and Mr. John Burns, teacher, father of the Rev. Dr. Burns, Barony

parish in that city, happened to be on guard the same night; and,

surprised to see the venerable clergyman in this attire, they recommended

him to go home to his prayers as more suitable to his vocation. “I am

determined, was his reply, “to take the hazard of the night along with

you, for the present crisis requires the arms as well as the prayers of

all good subjects.” [Life by Fraser, p. 439.] When Stirling was

taken possession of by the rebel forces, Mr. Erskine was obliged, for a

short period, to retire from the town, and his congregation assembled for

worship on Sundays, in the wood of Tullibody, a few miles to the north of

Stirling. So great, indeed, was the zeal displayed by him in the service

of the government that a letter of thanks was addressed to him by command

of the duke of Cumberland.

When the controversy concerning the lawfulness of swearing the religious

clause contained in the Burgess oath led, in April 1747, to the division

of the Secession church, Mr. Erskine was one of those who adhered to the

Burgher portion of the synod. In consequence of Mr. Moncrieff of

Abernethy, who held the office of professor of divinity to the associate

presbytery, adhering to the Antiburgher portion of the Secession, the

Burgher portion was left destitute of a professor; and Mr. Erskine

consented, at the request of his brethren, to fill the office, but, at the

end of two years, he resigned it on account of his health in 1749. He died

June 2, 1754, aged 74. He had been twice married; first, in 1704, to

Alison Turpie, daughter of a writer in Leven, by whom he had ten children,

and who died in 1720; and, secondly, in 1724, to Mary, daughter of the

Rev. James Webster, minister of the Tolbooth church, Edinburgh, by whom

also he had several children. His eldest daughter, Jean, was married to

the Rev. James Fisher of Glasgow. “During the night on which he finished

his earthly career, Mrs. Fisher, having come from Glasgow to visit her

dying father, was sitting in the apartment where he lay, and engaged in

reading. Awakened from a slumber, he said, ‘What book is that, my dear,

you are reading?’ ‘It is your sermon, father,’ she replied, ‘on that text,

I am the Lord thy God.’ ‘O woman,’ said he then, ‘that is the best

sermon ever I preached.’ The discourse had proved very refreshing to

himself, as well as to many of his hearers. A few minutes after that

expression had fallen from his lips, he requested his daughter to bring

the table and candle near the bed; and having shut his eyes, and laid his

hand under his cheek, he quietly breathed out his soul into the hands of

his Redeemer, on the 2d of June, 1754. Had he lived twenty days longer, he

would have finished the seventy-fourth year of his age; and had he been

spared three months more, he would have completed the fifty-first of his

ministry, having resided twenty-eight years at Portmoak, and nearly

twenty-three at Stirling.” [Life, by Dr. Fraser.] He published at

Edinburgh, in 1739, ‘The Sovereignty of Zion’s King,’ in some discourses

upon Psalm ii. 6. 12mo. In 1755 appeared a collection of his Sermons,

mostly preached upon Sacramental occasions, 8vo; and in 1757, three

volumes of his Sermons were printed at Glasgow in 1762, and a fifth at

Edinburgh in 1765. “Besides at least six volumes on ‘Catechetical

Doctrine,’” says Dr. Fraser, “

written

at Portmoak between 1717 and 1723, inclusive, he left in all forty-seven

notebooks of evangelical, sacramental, and miscellaneous sermons; fifteen

of which books were composed subsequently to his translation to Stirling.

Most of them consist of 220 pages; and all of them, with the exception of

a few words in common hand interspersed, are written in shorthand

characters. Each may contain on an average about thirty-six sermons of an

hour’s length. He left also several volumes of expository discourses,

including a series of lectures on the Epistle to the Hebrews, studied and

delivered immediately after his admission to his second charge.” [Life,

page 341.] The following is a list of his printed discourses:

The Sovereignty of Zion’s King; in some Discourses upon Psalm ii. 6. Edin.

1739, 12mo.

A

Collection of Sermons, mostly preached upon Sacramental Occasions. Edin.

1755, 8vo.

Discourses. 1757, 3 vols. 8vo.

Sermons, Glasgow, 1762, 4 vols, 8vo. A fifth vol. Edin. 1765.

ERSKINE,

RALPH,

one of the founders of the Secession Church, third son of the Rev. Henry

Erskine, minister of Chirnside, by his second wife, Margaret Halcro, was

born at the village of Monilaws, Northumberland, March 15, 1685. He was

educated, with his brother, Ebenezer, in the university of Edinburgh,

where he took the degree of M.A. in 1704. During his first session at

college, in the winter of 1699-1700, a great fire took place in the

Parliament-square, and the house in which he lodged being in that square

he narrowly escaped being burned to death. He had to force his way through

the flames, carrying a number of his books. Referring to this deliverance

a number of years afterwards, he mentions, in his diary, that on a day set

apart for private humiliation and prayer, he made it the subject of

grateful acknowledgment to God. “I took special notice,” says he, “of what

took place upon my first going to Edinburgh to the college, in the burning

of the Parliament close; and how mercifully the Lord preserved me, when he

might have taken me away in my sin, amidst the flames of that burning,

which I can say my own sins helped to kindle.” While engaged prosecuting

his theological studies, a considerable part of his time was spent in the

family of Colonel Erskine of Cardross, in the capacity of tutor. In June

1709 he was licensed to preach by the presbytery of Dunfermline, and, in

1711, he received a unanimous call from the parish of Tulliallan to become

their minister; and nearly at the same time he was unanimously called to

become the second minister in the collegiate charge of Dunfermline. The

latter he accepted. He was ordained on the 7th August of that

year, and about four years and a half after his ordination, Mr. Thomas

Buchanan his colleague died, and he was promoted to the first charge.

In

the controversy regarding the Marrow of Modern Divinity, Mr. Ralph Erskine

took a deep interest. The synod of Fife, of which he was a member, were

peculiarly strict in enforcing compliance with the act of Assembly, passed

in 1720, prohibiting all ministers from recommending the Marrow. As Mr.

Erskine did not choose to comply with this prohibition, he was formally

arraigned before the synod for noncompliance, and strictly charged to be

more obedient for the future, on pain of being subjected to censure. The

synod farther required that he, as well as the other Marrow-men within

their bounds, should subscribe anew the Confession of Faith, in a sense

agreeably to the Assembly’s deed of 1720. Mr. Erskine refused to submit to

this injunction; but professed his readiness to subscribe anew the

Confession of Faith, as received by the Church of Scotland in 1647. [supplement

to M’Kerrow’s History of the Secession Church, page 837.] In the

famous controversy with the General Assembly, which led to the Secession,

concerning the act of Assembly of 1732, with respect to the planting of

vacant churches, as related in the life of Ebenezer Erskine, his brother

Ralph Erskine adhered to all the protests that were entered in behalf of

the four brethren, and was present at Gaiorney Bridge, in December 1733,

when the latter formed themselves into the Associate Presbytery, although

he took no part in their proceedings. On the 18th of February,

1737, he formally joined himself to the Seceders, and was accordingly

deposed by the General Assembly, along with the other Seceding brethren,

in 1740.

Soon after entering on the ministry, he composed his ‘Gospel Sonnets,’

which have often been reprinted. About 1738 he published his poetical

paraphrase of ‘The Song of Solomon.’ Having frequently been requested by

the Associate Synod to employ some of his vacant hours in versifying all

the Scripture songs, he published, in 1750, a new version of the Book of

Lamentations. He had also prepared ‘Job’s Hymns’ for the press, but they

did not appear till after his decease. When the rupture took place in the

Associate Synod in 1747 on account of the Burgess oath, Mr. Erskine joined

the Burgher section, while his son Mr. John Erskine, minister at Leslie,

adhered to the Antiburghers. His son James became colleague and successor

to his uncle, Ebenezer, at Stirling in January 1752.

Mr. Erskine died of a nervous fever, November 6, 1752. He was twice

married; first, to Margaret daughter of Mr. Dewar of Lassodie, by whom he

had ten children; and, secondly, to Margaret, daughter of Mr. Simpson,

writer to the signet, Edinburgh, by whom he had four children. It is

related that the only amusement in which this celebrated divine indulged

was playing on the violin. He was so great a proficient on this

instrument, and so often beguiled his leisure hours with it, that the

people of Dunfermline believed he composed his sermons to its tones.

His son, Henry, in a letter addressed to a relative, giving an account of

his father’s death, says: “He preached here last Sabbath save one with

very remarkable life and fervency. He spoke but little all the time, that

the disease did not evidently appear to be present death approaching; the

physicians having ordered care to be taken to keep him quiet. But after he

had taken the remarkable and sudden change to the worse, which was not

till Sabbath, he then spoke a great deal, but could not be understood.

Only among his last words he was heard to say, ‘I will be for ever a

debtor to free grace,’” Mr. Whitefield, giving an account of the last

expressions of several dying Christians, in a sermon preached from Isa.

lx. 19, says, “Thus died Mr. Ralph Erskine. His last words were, ‘Victory,

victory, victory!’” Mr. Erskine, as a preacher, is said to have had a

“pleasant voice, an agreeable manner, a warm and pathetic address.” In his

public appearances, he endeavoured to adapt himself to the capacity of his

audience; and, instead of using the ‘enticing words of man’s wisdom,’ he

addressed to them the truths of the gospel in their genuine purity and

simplicity. His style was strictly evangelical and experimental.

On

the 27th of June, 1849, a monument to his memory was formally

inaugurated at Dunfermline. The monument, which consists of a statue of

the venerated Seceder, modelled and sculptured in Berrylaw stone by Mr.

Handyside Ritchie, is placed on an appropriate pedestal in the area in

front of the Queen Anne Street church, of the congregation attending which

Mr. Ralph Erskine was minister. The figure is of a large monumental size,

and represents Erskine in the dress of the period in which he lived – the

full skirted coat, with large cuffs, breeches, and stockings, the clerical

costume of the middle of the 18th century.

The greater part of Ralph Erskine’s works were originally printed in

single sermons and small tracts. The following is a list of them:

Sermons: with a Preface by the Rev. Dr. Bradbury. London, 1738.

Gospel Compulsion: a Sermon, preached at the Ordination of Mr. John

Hunter. Edin. 1739, 12mo.

Four Sermons of Sacramental Occasions, on Gal. ii. 20. Edin. 1740, 12mo.

Chambers of Safety in Time of Danger; a Fast Sermon. Edin. 1740, 12mo.

A

Sermon. Glasg. 1747, 12mo.

Clean Water; or, The Pure and Precious blood of Christ, for the Cleansing

of Polluted Sinners; a Sermon on Ezekiel xxxvi. 25. Glasg. 1747, 12mo.

A

New Version of the Song of Solomon, into Common Metre. Glasg. 1752, 12mo.

Job’s Hymns; or, a Book of Songs on the Book of Job. Glasg. 1753, 8vo.

Scripture Songs, in 3 parts. Glasg. 1754, 12mo.

Gospel Sonnets; or, Spiritual Songs, in six parts, 25th

edition, in which the Holy Scriptures are fully extended. Edin. 1797. 8vo.

Faith no Fancy, or, a Treatise of Mental Images.

The Harmony of the Divine Attributes Displayed in the Redemption and

Salvation of Sinners by Jesus Christ; a Sermon preached at Dunfermline,

1724, from Psalm lxxxv. 10. Falkirk, 1801, 12mo.

A

Short Paraphrase upon the Lamentations of Jeremiah, adapted to the common

times. Glasg. 8vo.

His Works; consisting principally of Sermons, Gospel Sonnets, and a

Paraphrase in Verse of the Song of Solomon, were published at Glasgow,

1764-6, 2 vols. fol. Afterwards printed in 10 vols. 8vo.

ERSKINE,

HENRY,

third Lord Cardross, an eminent patriot, eldest son of David, second Lord

Cardross, by his first wife, Anne, fifth daughter of Sir Thomas Hope,

king’s advocate, was born in 1650, and succeeded to the title in 1671. He

had been educated by his father in the principles of civil and religious

liberty, and he early joined himself to the opposers of the earl of

Lauderdale’s administration, in consequence of which he was exposed to

much persecution. In 1674 he was fined £5,000 for the then serious offence

of his lady’s hearing divine worship performed in his own house by her own

chaplain. Of this fine he paid £1,000, and after sic months’ attendance at

court, in the vain endeavour to procure a remission of the rest, he was,

on August 5, 1675, imprisoned in the castle of Edinburgh, wherein he

continued for four years. In May of that year, while his lordship was at

Edinburgh, a party of soldiers went to his house of Cardross at midnight,

and after using his lady with much rudeness and incivility, fixed a

garrison there to his great loss. In 1677 his lady having had a child

baptized by a non-conforming minister, he was again fined in £3,000,

although it was done without his knowledge, he being then in prison. In

June 1679, the king’s forces, on their march to the west, went two miles

out of their road, in order that they might quarter on his estates of

Kirkhill and Uphall, in West Lothian.

On

July 30, 1679, Lord Cardross was released, on giving bond for the amount

of his fine, and, early in 1680, he repaired to London, to lay before the

king a narrative of the sufferings which he had endured; but the Scottish

privy council, in a letter to his majesty, accused him of

misrepresentation, and he obtained no redress. His lordship now resolved

upon quitting his native country, and accordingly proceeded to North

America, and established a plantation on Charlestown Neck, in South

Carolina. In a few years he and the other colonists were driven from this

settlement by the Spaniards, when his lordship returned to Europe, and

arriving at the Hague, attached himself to the friends of liberty and the

Protestant religion, then assembled in Holland. He accompanied the prince

of Orange to England in 1688; and having, in the following year, raised a

regiment of dragoons for the public service, he was of great use under

General Mackey in subduing the opposition to the new government. In the

parliament of 1689 he obtained an act restoring him to his estates. He was

also sworn a privy councillor, and constituted general of the mint. He

died at Edinburgh May 21, 1693, in the 44th year of his age.

ERSKINE,

JOHN,

eleventh earl of Mar, or Marr, as it was originally spelt, eldest son of

Charles, tenth earl of the name of Erskine, and Lady Mary Maule, daughter

of the earl of Panmure, was born at Allow, in February 1675. He succeeded

his father in 1689, and, on coming to the title, found the family estates

much involved. Following the footsteps of his father, who joined the

revolution party, merely because he considered it his interest so to do,

the young earl, on entering into public life, attached himself to the

party then in power, at the head of which was the duke of Queensberry, the

leader of the Scottish Whigs. He took the oaths and his seat in parliament

in Sept. 1696, was sworn in a privy councillor the following year, and was

afterwards appointed to the command of a regiment of foot, and invested

with the order of the Thistle. In 1704, when the whigs were superseded by

the country party, the earl, pursuant to the line of conduct he intended

to follow, of making his politics subservient to his interest, immediately

paid court to the new administration, by placing himself at the head of

such of the duke of Queensberry’s friends as opposed the marquis of

Tweeddale and his party. In this situation he showed so much dexterity,

and managed his opposition with so much art and address, that he was

considered by the Tories as a man of probity, and well inclined to the

exiled family. Afterwards, when the Whig party came again into power, he

gave them his support, and became very zealous in promoting all the

measures of the court, particularly the treaty of union, for which he

presented the draught of an act in parliament, in 1705. To reward his

exertions, he was, after the prorogation of the parliament, appointed

secretary of state for Scotland, instead of the marquis of Annandale, who

was displaced, because he was suspected of holding a correspondence with

the squadron, who were inclined to support the succession to the

crown without, rather than with, the proposed union. His lordship was

chosen one of the sixteen representative peers in 1707, and re-elected at

the general election the following year, and in 1710 and 1713. By the

share he had taken in bringing about the union, Mar had rendered himself

very unpopular in Scotland; but he endeavoured to regain the favour of his

countrymen, by attending a deputation of Scottish members, consisting of

the duke of Argyle, himself, Cockburn, younger of Ormiston, and Lockhart

of Carnwath, which waited on Queen Anne in 1712, to inform her of their

resolution to move for a repeal of the union with England. When the earl

of Findlater brought forward a motion for repeal in the house of lords,

Mar spoke strongly in favour of it, and pressed the dissolution of the

union as the only means to preserve the peace of the island. He was made a

privy-councillor in 1708, and on the death of the duke of Queensberry in

1713, the earl was again appointed secretary of state for Scotland, and

thus for the second time joined the Tory party.

On

the death of Queen Anne, on the 1st of August 1714, the schemes

of the Bolingbroke ministry having been baffled by the activity of the

leaders of the whigs, his lordship, secretary of state, signed the

proclamation of George I., and in a letter to the king, then on his way

through Holland, dated Whitehall, August 30, made protestations of his

loyalty, and reference to his past services to the government. He likewise

procured a letter to be addressed to himself by some of the heads of the

Jacobite clans, sais to be drawn up by Lord Grange, his brother, but

evidently his own composition, declaring that as they had always been

ready to follow his lordship’s directions in serving Queen Anne, they were

equally ready to concur with him in serving his majesty. A loyal address

of the clans to the king to the same effect was drawn up by his brother,

Lord Grange, which, on his majesty’s arrival at Greenwich, he intended to

present. But the king was too well aware that, in order to ingratiate

himself with Queen Anne, he had procured from the same parties an address

of a very opposite character only a few years previous. He was accordingly

unnoticed on presenting himself to the king on his landing, and dismissed

from office within eight days afterwards.

Though not possessed of shining talents, he made ample amends for their

deficiencies by artifice and an insinuating and courteous deportment, and

managed his designs with such prudence and circumspection as to render it

extremely difficult to ascertain his object when he desired concealment;

by which conduct “he showed himself,” in the opinion of a contemporary,

“to be a man of good sense, but bad morals.” [Lockhart, vol. i., p.

436.] The versatility of his politics was perhaps owing rather to the

peculiar circumstances in which he was placed than to any innate

viciousness of disposition. He was a Jacobite from principle, but as the

fortunes of his house had been greatly impaired in the civil war by its

attachment to the Stuarts, and, as upon his entrance into public life, he

found the cause of the exiled family at a low ebb, he sought to retrieve

the losses which his ancestors had sustained; while, at the same time, he

gratified his ambition, by aspiring to power, which he could only hope to

acquire by attaching himself to the existing government. The loss of a

place of five thousand pounds a-year, without any chance of ever again

enjoying the sweets of office, was gall and wormwood to such a man. This

disappointment, and the studied insult he had received from the king,

operating upon a selfish and ambitious spirit, drove him into open

rebellion, with no other view than the gratification of his revenge. But

whatever were his qualifications in the cabinet, he was without military

experience, and consequently unfit to command an army, as the result

showed.

As

early as May 1715, a report was current among the Jacobites of Scotland,

of the design of the Chevalier de St. George to make a descent on Great

Britain, in order to recover the crown, in consequence of which they began

to bestir themselves, by providing arms, horses, &c. These and other

movements indicated to the government that an insurrection was intended.

Bodies of armed men were seen marching towards the Highlands, and a party

of Highlanders appeared in arms near Inverlochy, which was, however, soon

dispersed. In this situation of matters, the lords-justices sent down to

Scotland a considerable number of half-pay officers, to officer the

militia of the country, under the direction of Major-General Whitham, then

commander-in-chief in Scotland. These prompt measures alarmed the

Jacobites, who, after several consultations, returned to their homes. As

the lords-justices had received information that the chevalier intended to

land in North Britain, they offered a reward of £100,000 sterling for his

apprehension.

On

the eve of Mar’s departure from England, to place himself at the head of

the intended insurrection in Scotland, he resolved to show himself at

court; and, accordingly, he appeared in the presence of King George on the

first of August, 1715, with all the complaisance of a courtier, and with

that affability of demeanour for which he was so distinguished.

Having matured his plans and apprised his confederates, he disguised

himself by changing his usual dress, and on the following day embarked at

Gravesend on board a collier bound for Newcastle. On arriving there he

went on board another vessel bound for the Firth of Forth, and was landed

at Elie, a small port on the Fife coast, near the mouth of the Firth.

Visiting various Jacobite friends on his way, he reached his seat of

Kildrummy in the Braes of May on the 18th, and on the following

day summoned a meeting of the neighbouring noblemen and gentlemen to a

grand hunting match at Aboyne on the 27th, which was numerously

attended, and where he addressed them in a regular and well ordered

speech. The result was an unanimous resolution to take up arms. According

to arrangements at a subsequent meeting at the same place on 3d September,

he on the 6th set up the standard of the Pretender at

Castletown of Braemar, assuming the title of lieutenant-general of his

majesty’s forces in Scotland. The Chevalier was about the same time

proclaimed king, under the name of James VIII., at Aberdeen, and various

other towns. The earl immediately marched to Dunkeld, and, after a few

days’ rest, to Perth, where he established his headquarters. Finding his

army increased to about 12,000 men, he resolved to attack Stirling, and

accordingly left Perth on November 10; but encountered the royal army,

under the command of the Duke of Argyle, at Sheriffmuir, near Dunblane, on

the 13th, when the advantage was on the side of the king’s

troops, the rebels being compelled to return to Perth.

The unfortunate and ill-advised James having landed at Peterhead from

France, December 22, 1715, the earl, now created by him duke of Mar,

hastened to meet him at Fetteresso, and attended him to Scone, where he

issued several proclamations, distinguished, like all his previous ones,

by great ability, including one for his coronation of January 23; but soon

after they removed to Perth, where it was resolved to abandon the

enterprise. The Pretender, with the earl of Mar, Lord Drummond, and

others, embarked at Montrose, February 4, in a French ship which had been

kept off the coast, and were landed at Waldam, near Gravelines, February

11, 1716. For his share in this rebellion, the earl was attainted by act

of parliament, and his estates forfeited.

His lordship accompanied the Pretender to Rome, and remained in his

service for some years, having the chief direction of his affairs. Having,

soon after his return, been violently accused by Bolingbroke – his former

superior in the English ministry – with regard to the conduct of the

rebellion in 1715, he, in order to revenge himself on his rival, prevailed

on the duke of Ormond to report, in presence of the Chevalier, certain

abusive expressions which Bolingbroke, when in a state of intoxication,

had uttered in disparagement of his master. Bolingbroke was, in

consequence, deprived of the seals, then possessed by him. He thereupon

proffered his services to King George, and some years afterwards obtained

a pardon and had his estates restored to him. IN 1721 the earl of Mar left

Rome, and, after a short residence in Geneva, where he was subjected to a

brief confinement at the instance of the British government, he took up

his residence at Paris as minister of James at the French court. During

his residence in Geneve, he applied for and received a loan from the earl

of Stair, the British ambassador at Paris, and soon thereafter accepted a

pension of two thousand pounds from the British government, which, at the

same time, allowed his countess and daughter one thousand five hundred

pounds annually, of jointure and aliment, out of the produce of his

estate.

These relations with the British ministry, however, induced James

gradually to withdraw his confidence from him, and being involved in

disputes with parties connected with the household, and accused by Bishop

Atterbury of having betrayed the secrets of his master to the English

ministry, he was in 1724 dismissed from his post as minister at Paris, and

finally broke with the Stuarts in 1725. He prepared a narrative in

exculpation, and although his justification is far from complete, it is

evident that there exist no sufficient data on which to found a charge of

deliberate treachery. His negociations with the earl of Stair, the British

ambassador in France, for a pardon, which, however, were unsuccessful, are

printed in the Hardwicke Collection of State Papers. In 1729, on account

of the bad state of his health, he went to Aix-la-Chapelle, where he died

in May 1732. His lordship was twice married; first, to Lady Margaret Hay,

daughter of the earl of Kinnoul, by whom he had two sons; and, secondly,

to Lady Frances Pierrepont, daughter of Evelyn, duke of Kingston, by whom

he had one daughter. His principal occupation in his exile was the drawing

of architectural plans and designs. His forfeited estates were bought of

government for his son Lord Erskine, by the uncle of the latter, Erskine

of Grange.

ERSKINE,

JOHN,

of Carnock, an eminent lawyer, son of the Hon. Colonel John Erskine of

Carnock, third son of Lord Cardross by his second wife Anne, eldest

daughter of William Dundas of Kincavel, was born in 1695. His father, from

his conscientious support of the presbyterian church, and the civil and

religious liberties of the country, during the arbitrary reign of James

the Second of England, was obliged to retire to Holland, where he obtained

the command of a company in a regiment of foot, in the service of the

price of Orange. He was one of the most zealous supporters of the

revolution of 1688, and on the occurrence of that event he accompanied the

prince to England. As a reward for his service and attachment, he was

appointed lieutenant-governor of Stirling castle, and a lieutenant-colonel

of a regiment of foot, and afterwards received the governorship of the

castle of Dumbarton. In the last Scottish parliament, he was

representative of the town of Stirling, and was a great promoter of the

union. In 1707 he was nominated to a seat in the united parliament of