MALCOLM, a surname originally

Gilliecolane or Gillechallum, derived from two Gaelic words

signifying the servant of St. Columba. Somerled, thane of

Argyle, had a son of this name, who was slain with him near

Renfrew in 1164.

The chief of

the clan Challum or the MacCallums, an Argyleshire sept.

originally styled the clan Challum of Ariskeodnish, is Malcolm

of Poltalloch, whose family has been settled from a very early

period in that county. One of this house, called Zachary Und

Donald Mor of Poltalloch, was killed May 25, 1647, at Ederline,

in South Argyle, in single combat with Sir Alexander Macdonald,

called Allaster Mac Collkittoch, or left-handed. He was in the

force of the marquis of Argyle when General David Leslie

advanced into Kintyre to drive out the royalists, and was

renowned in his day for his great strength. It is alleged that

he slew seven of his assailants before he was himself slain. He

was getting the better of Colkitto, when a Maclean came behind

him with a scythe and hamstrung him; he was then easily

overpowered.

In 1414, Sir

Duncan Campbell of Lochow granted to Reginald Malcolm of

Corbarron, certain lands of Craignish, and on the banks of Loch

Avich, in Nether Lorn; with the office of hereditary constable

of his castles of Lochaffy and Craignish. This branch became

extinct towards the end of the 17th century, as Corbarron or

Corran is said to have been bequeathed by the last of the family

to Zachary MacCallum of Poltalloch, who succeeded his father in

1686.

Dugald

MacCallum of Poltalloch, who inherited the estate in 1779,

appears to have been the first to adopt permanently the name of

Malcolm as the family patronymic. Besides Poltalloch, the family

possesses Kilmartin house and Duntroon castle, in the same

county.

John Malcolm,

Esq., of Poltalloch, born in 1805, a magistrate and

deputy-lieutenant for Argyleshire and Kent, succeeded his

brother, Neill, in 1857. Educated at Harrow and Oxford, he

became B.A. in 1827 and M.A. in 1830. He married 2d daughter of

the Hon. John Wingfield, Stratford, son of 3d Viscount

Powerscourt, with issue. Heir, his son, John Wingfield.

_____

The Malcolms of

Balbeadie and Grange, Fifeshire, POSSESS A BARONETCY OF Nova

Scotia, conferred in 1665. In the reign of Charles I., Sir John

Malcolm, eldest son of John Malcolm of Balbeadie, acquired the

lands of Lochore in the same county. A branch of the Malcolms of

Lochore and Innertiel settled in Dumfries-shire.

In 1746, Sir

Michael Malcolm, baronet, being related to the last Lord

Balmerino, was sent for to be present at his execution on

Tower-hill. A daughter of lord Chancellor Bathurst saw him on

the scaffold, and fell in love with him. He subsequently married

her.

On Sir

Michael’s death, the title devolved upon James Malcolm of

Grange, and at the death of the latter in 1795, upon John

Malcolm of Balbeadie, descended from the youngest brother of the

first baronet. Sir John’s son, Sir Michael Malcolm, married in

1824, Mary, youngest daughter of John Forbes, Esq., of Bridgend,

Perth, and with three daughters, had one son, Sir John Malcolm,

born April 1, 1828, who succeeded to the baronetcy, on the death

of his father in 1833.

MALCOLM I., King of Scots, was the son

of Donal IV., who reigned from 893 to 904. On the abdication of

Constantine III., Malcolm succeeded to the throne in 944. In

945, Edmund, the Saxon king of England, ceded Cumberland and

part of Westmoreland to him, on condition that he would defend

that northern territory, and become the ally of England. Edred,

the brother and successor of Edmund, accordingly applied for,

and obtained the aid of Malcolm against Anlaf, king of

Northumberland, which latter country he wasted, and carried off

the inhabitants with their cattle.

In the time of

Malcolm I., the people of the province of Moray, in the

north-east of Scotland, were a mixed race, formed of

Scandinavian settlers, with Scottish and Pictish Celts.

Turbulent and rebellious, they were continually at war with the

sovereign, and an insurrection having occurred under Cellach,

maormor of Garmoran, Malcolm marched north to reduce them to

obedience. He slew Cellach, but was, some time thereafter,

assassinated in 953 at Ulurn, supposed by Shaw to be Auldearn,

after a reign of nine years. Other accounts state his death to

have taken place at Fodresach or Forres. He was succeeded by

Indulph, the son of Constantine II., and Indulph had for his

successor, Duff, the son of Malcolm, who mounted the throne in

961. Another son of Malcolm I., Kenneth III., succeeded in 971,

after an intermediate possessor of the throne named Culen, the

son of Indulph.

MALCOLM II, King of Scots, the son of

Kenneth III., succeeded to the throne in 1003, and had a

troublous reign of about thirty years. He defeated and slew

Kenneth IV. at Monievaird in Strathearn, and in consequence

became king. His first annoyance came from the Danes who, in

previous reigns, had made several attempts to effect a

settlement in Scotland, but had been defeated in them all. They

had secured a firm footing in England, and the year after

Malcolm’s accession to the throne, they commenced the most

formidable preparations, under their celebrated king, Sweyn, for

a new expedition to the Scottish coasts. He ordered Olaus, his

viceroy in Norway, and Enet in Denmark, to raise a powerful

army, and to fit out a suitable fleet for the enterprise.

The coast of

Moray was chosen as the scene of the menaced invasion. Effecting

a descent near Speymouth, the Danes carried fire and sword

through that province, and laid siege to the fortress of Nairn,

then one of the strongest castles in the north of Scotland. They

were forced to raise the siege for a time by Malcolm, who

hastening against them with an army, encamped in a plain near

Killflow or Kinlos. In this position he was attacked by the

Danes, and forced to retreat, after being seriously wounded. The

fortress of Nairn then capitulated to the invaders, but in

violation of an express condition that their lives should be

saved, the whole garrison were immediately hanged.

To expel the

Danes from Moray, Malcolm mustered all his forces, and in the

spring of 1010, with a powerful army he encamped at Mortlach.

The Danes advanced to give him battle, and a fierce and

sanguinary conflict ensued, the result of which was long

doubtful. Three of the Scottish commanders fell at the very

commencement of the engagement, when a panic seized their

followers, and the king was borne along with them in their

retreat till he was opposite the church of Mortlach, then a

chapel dedicated to St. Molach. There, while his army were

partially pent up in their flight by the contraction of the vale

and the narrowness of the pass, he made a vow to endow a

religious house on the field of battle should he obtain the

victory. Then, rallying and rousing his troops by an animated

appeal to their patriotism, and placing himself at their head,

he wheeled round upon the Danes, threw Enotus, one of the Danish

generals, from his horse, and killed him with his own hand. The

Scots, catching his spirit, made an impetuous onset on the

enemy, whom they drove from the field, thickly strewing the

ground with their corpses. In gratitude to God for this signal

victory, Malcolm got the church of Mortlach converted into a

cathedral, and the village into the seat of a diocese, said to

have been the earliest bishopric in Scotland. His endowment of

it was confirmed by Pope Benedict, but in 1139 the bishopric was

removed to Aberdeen. In the order of precedence, while this see

lasted, it ranked next to that of St. Andrews. It was long

thought that, during their occupation of Moray, the Danes had

fortified Burgh Head, but the remains there found are now

believed to be either of roman or Pictish construction.

To revenge this

defeat and other disasters which, at this time, the invaders

experienced on the coasts of Angus and Buchan, Sweyn, the Danish

king, dispatched Camus, one of the ablest of his generals, to

the Scottish shores. He had scarcely, however, effected a

landing on the coast of Angus, in the neighbourhood of

Carnonstie, than he was attacked in the plains of Barrie by

Malcolm, at the head of a considerable army, and, after a bloody

contest, defeated with great loss. He sought safety in flight,

but was closely pursued, and killed. The place of his overthrow

is indicated by a monumental stone, called the Cross of Camus,

which stands on a small tumulus at Camustown, a village which

has been named after him, in the parish of Monikie. The tumulus,

according to tradition, contains the remains of Camus, and the

story of the old chroniclers is that, after his defeat, he fled

northwards, with a view to escape to Moray, where were some of

his ships, but was pursued and overtaken here by Robert, the

remote ancestor of the earls Marischal, who killed him by

cleaving his skull with his battle-axe. About the year 1620, the

tumulus was opened by order of Sir Patrick Maule, afterwards

first earl of Panmure, when a skeleton of large dimensions in

good preservation was discovered, with part of the skull

wanting.

The Danes,

however, were not to be deterred even by the repeated defeats

which they had sustained, from their long cherished but often

baffled scheme of the conquest of North Britain. And as for the

Scots, the spirit which animated them has been well expressed in

the lines of Home:

“The Danes have

landed, we must beat them back,

Or live the

slaves of Denmark.

In 1014,

another Danish force landed on the coast of Buchan, about a mile

west from Slaines castle, in the parish of Cruden. The Danes on

this occasion were led by Sweyn’s celebrated son, Canute,

afterwards king of England and Denmark, and again they

experienced a signal overthrow. The site of the field of battle

has been ascertained by the discovery of human bones left

exposed by the shifting or blowing of the sand. Some writers

assert that a treaty was entered into with the Danes, by which

it was stipulated that the field of battle should be consecrated

by a bishop as a burying-place for those of their countrymen who

had fallen, and that a church should be there built and priests

appointed in all time coming, to say masses for the souls of the

slain. It is certain that a chapel was erected in this

neighbourhood, dedicated to St. Olaus, the site of which has

become invisible by being covered with sand. Another and far

more important stipulation, it is said, was made by which the

Danes agreed to quit every part of the Scottish coasts, and this

was followed by the final departure, the same year, of these

ruthless invaders from Scotland.

Malcolm was

next engaged in war with the Northumbrians, and having, in 1018,

led his army to Carham, near Werk, on the southern bank of the

Tweed, he was met there by Uchtred earl of Northumberland, when

a desperate battle took place. The victory was claimed by

Uchtred, who was, soon after, assassinated, when on his way to

pay his obeisance to the great Canute. To prevent an invasion of

his territories, Eadulph, his brother and successor, in the year

1020, ceded to Malcolm the fertile region of Lodonia, or

Lothian. That extensive and beautiful district had formerly been

a part of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria, which in the

time of Edwin, from whom Edinburgh derives its name, and who

began his reign in 617, had extended from the Humber to the

Avon; but ever after it had thus been acquired by Malcolm II.,

it formed an integral portion of the Scottish dominions. On this

occasion, Malcolm gave oblations to the churches and gifts to

the clergy, who, in return, bestowed on him the proud

designation of vir victoriosissimus.

In 1031, Canute,

the Danish king of England, the most powerful monarch of his

time, invaded Scotland, to compel Malcolm to do homage for

Cumbria, which he had refused, on the ground that Canute was a

usurper; but, after some negotiations, Duncan, Malcolm’s

grandson, afterwards king, agreed to fulfil the conditions on

which that territory had been granted to the Scots, and Canute

immediately returned to England.

Malcolm died in

1033, and was buried at Iona, the usual place of sepulcher, for

many centuries, of the Scottish kings.

[picture of Iona]

Both Boece and

Fordun assert that Malcolm II. Was murdered in the central tower

of the castle of Glammis in Forfarshire, which seems to have

been his usual place of residence. Wyntoun states that the cause

of the insurrection which led to his assassination was that he

had ravished a virgin. His words are:

“----------he

had rewyist a fayre May

Of the land

there lyand by.”

Tradition still pretends to point out a

passage in the castle, with blood-stains on the floor, where the

fatal act was perpetrated. It avers also that the ground being

covered with snow, the assassins, in their flight, mistook their

way, and unconsciously entered on the loch of Forfar, when the

ice broke, and they were drowned; a very convenient method of

getting rid of imaginary murderers. The whole story is a fiction

of that fertile inventor of Scottish history, Hector Boece, and

is totally incredible, even although no less than three

obelisks, with symbolic characters, representative of the

conspiracy and the pursuit of the fancied regicides, have for

centuries stood in different parts of the parish of Glammis, to

commemorate it. Pinkerton (Enquiry, vol. ii. p. 192) contends

that Malcolm died a natural death, which is more likely than the

fabulous account of his assassination.

The

authenticity of the pretended laws of Malcolm, called the Leges

Malcolmi, has been denied by Lord Hailes. He, however,

introduced many improvements into the internal policy of his

kingdom, and in him the church always found a guardian and

benefactor.

Malcolm’s

daughter, Bethoc, married Crinan, abbot of Dunkeld, and this

marriage gave a long line of kings to Scotland, ending with

Alexander III. Their son, Duncan, succeeded his maternal

grandfather on the throne, and was “the gracious Duncan,”

murdered by Macbeth. Crinan is styled by Fordun, Abthanus de

Dull ac Seneschallus Insularum. The title of abthane appears to

have belonged to an abbot who possessed a thanedom. It was

peculiar to Scotland, and only three abthaneries are named in

ancient records, namely, those of Dull in Athol, Kirkmichael in

Strathardie, and Madderty in Strathearn. The title of thane,

previously known in England, was not used in Scotland till the

introduction of the Saxon policy into the latter kingdom by

Edgar, who began his reign in 1097. The three thanedoms

mentioned under the name of Abthaneries appear to have been

vested in the crown, and were conferred by Edgar on his younger

brother, Ethelred, who was abbot of Dunkeld. On Ethelred’s death

they reverted to the crown.

In the time of

Crinan, “there was certainly,” says Mr. Skene, “no such title in

Scotland, but it is equally certain that there were no charters,

and although Crinan had not the name, he may have been in fact

the same thing. He was certainly abbot of Dunkeld, and he may

have likewise possessed that extensive territory which, from the

same circumstance, was afterwards called the abthanedom of Dull.

Fordun certainly inspected the records of Dunkeld, and the

circumstance can only be explained by supposing that Fordun may

have there seen the deed granting the abthanedom of Dull to

Ethelred, abbot of Dunkeld, which would naturally state that it

had been possessed by his proavus Crinan, and from which Fordun

would conclude that as Crinan possessed the thing, he was also

known by the name of Abthanus de Dull. From this, therefore, we

learn the very singular fact that the race which gave a long

line of kings to Scotland, were originally lords of that

district in Athol lying between Strathtay and Rannoch, which was

afterwards termed the Abthania de Dull.” (Skene’s Highlands of

Scotland, vol. ii. pp. 137. 138.)

Departing from

the generally received history of Scotland at this remote and

confused period of our annals, Mr. Skene is of opinion, from the

remarkable coincidence which he found between the Irish annals

and the Norse Sagas, that two Malcolms of different families

reigned in Scotland during the thirty years allotted to one, the

second of these Malcolms being in possession of the throne the

last four years of that time. From his account of the second

Norwegian kingdom in the north of Scotland, which lasted only

seven years, that is, from 986 to 993 (vol. i. p. 108), we learn

that Sigurd, the 14th iarl of Orkney, after having defeated a

Celtic army under Kenneth and Melsnechtan, maormors of Dala

(Argyle) and Ross, in an attempt on their part to recover

Caithness, in which Melsnechtan was slain, was obliged to retire

to the Orkneys, by the approach of Malcolm, maormor of Moray,

with a large Scottish force, and he was never afterwards able to

regain a footing on the mainland of Scotland. He had previously

made himself master of the districts of Ross, Moray, Sutherland,

and Argyle, but had been driven out of them by a sudden rising

of their maormors. These districts were left in possession of

Malcolm, who was enabled, by his increased power and influence,

and great personal talents, even to seat himself on the throne

itself. It what his title to the crown consisted is not known,

but whatever it was, he was supported in it by the Celtic

inhabitants of the whole of the north of Scotland. His

descendants, for many generations afterwards, constantly

asserted their right to the throne, and as invariably received

the assistance of the Celtic portion of its inhabitants. “In all

probability,” says Mr. Skene, “the Highlanders were attempting

to oppose the hereditary succession in the family of Kenneth

M’Alpin, and to introduce the more ancient Pictish law.” Kenneth

III. Is said to have got a law passed by his chiefs, on the

moothill of Scone, that the son, or nearest male heir of the

king, should always succeed to the throne, and when not of age,

that a regent should be appointed to rule the kingdom in his

name until he attained his fourteenth year, when he should

assume the reins of government. As the sovereignty was not

transmitted by the strict line of hereditary descent, brothers,

by the law of tanistry, being preferred to sons in the

succession, rival contests and civil wars for the crown were

frequent. Kenneth’s law, if passed at all, of which there is no

evidence, seems not to have been acted upon, as two princes,

Constantine IV., the son of Culen, (mentioned earlier), and

Kenneth IV. the son of Duff, succeeded to the crown before

Malcolm; that is, on the hitherto received supposition that

Malcolm II. was the son of Kenneth III., and grandson of Malcolm

I. If such was the case, Kenneth IV., the son of Duff, was his

cousin, and, during his reign, Malcolm stood in the position of

heir presumptive to the crown, and was regulus or prince of

Cumberland.

According to

Skene, however, he was maormor of Moray, and so far as appears,

not allied to the royal family at all. He seems to have made war

on Kenneth IV., but by the interposition of Fothad, one of the

Scottish bishops, a treaty was agreed to between them, by which

it was stipulated that Kenneth should remain king for life, and

that Malcolm and his heirs should succeed after him. Impatient

to possess the crown, however, Malcolm again took the field, and

in a bloody battle at Monivaird in Strathearn, Kenneth, after a

brave resistance, was killed. According to the register of St.

Andrews, Kenneth was slain “at Moleghvard,” in 1001. Other

accounts make it 1003.

Soon after

becoming king of Scotland, to conciliate Sigurd, earl of Orkney,

called the Stout, and described as “a great chieftain and

wide-landed,” Malcolm gave him his daughter for his second wife.

The issue of this marriage was four sons. The eldest, Thorfinn,

is said in the Orkneyinga Saga, to have been “a great chieftain,

one of the largest men in point of stature, ugly of aspect,

black haired, sharp featured, and somewhat tawny, and the most

martial looking man; he was a contentious man, and covetous both

of money and dignity; victorious and clever in battle, and a

hold attacker. He was then five winters old when Malcolm, king

of the Scots, his mother’s father, gave him an iarl’s title, and

Caithness to rule over, but he was fourteen winters when he

prepared maritime expeditions from his country, and made war on

the domains of other princes.” He thus early began his career as

a Vikingr. It was on the death of his father Sigurd, who was

slain in 1014, at the battle of Clontarf in Ireland, fighting

against the renowned Brian Borohime, that King Malcolm bestowed

on him the district of Caithness, his eldest half-brother, Einar,

having succeeded to the iarldom of the Orkneys.

In the Irish

annals, under the year 1029, it is recorded that “Malcolm, son

of Maelbrigde, son of Rory, King of Alban, died.” His reign

would thus appear to have lasted only twenty-six, instead of

thirty years. On his death, the Scottish portion of the nation

succeeded in placing upon the throne the son of Kenneth IV.,

also named Malcolm, for whom, according to Mr. Skene’s view, he

has been mistaken. In the Orkneyinga Saga he is known by the

name of Kali Hundason, and in the history of Scotland, of

Malcolm II.

This third

Malcolm commenced his reign by attempts to reduce the power of

the Norwegians in Scotland, but found them too strong for him.

Thorfinn having refused to pay him tribute for the territories

on the Scottish mainland, which he had received from his

grandfather, Malcolm gave Caithness to Moddan, his nephew, with

the title of iarl. To enable him to take possession of his new

territory, Moddan raised an army in Sutherland, but Thorfinn

collected his followers, and having been joined by Thorkell

Fostri, with a large force from the Orkneys, presented such a

strong front, that Moddan found himself obliged to retire

without hazarding a battle. On this Thorfinn subjected to

himself Sutherland and Ross, and carried his arms far and wide

in Scotland. He then returned to Caithness.

Malcolm, on his

part, with a fleet of eleven ships, sailed towards the north,

but was attacked and defeated in the Pentland Firth by Thorfinn,

and his fleet completely dispersed. This sea-fight took place a

little way east of Durness. Malcolm fled to the Moray Firth,

followed by Thorfinn and Thorkell. The latter, however, was soon

dispatched to Thurso, to attack Moddan, who had arrived there

with a large army. He reached Thurso at night, and having set

fire to the house in which Moddan slept, that chieftain leapt

down from the beams of an upper story, and was slain by Thorkell,

who cut off his head. After a brief fight, during which a great

number were killed, his army surrendered to Thorkell, who, with

additional forces, then rejoined Thorfinn in Moray.

In the

meantime, Malcolm had levied forces both in the east and west of

Scotland, and having been joined by a number of Irish

auxiliaries, he marched to give battle to Thorfinn. The opposing

armies met in 1033, on the southern shore of the Beauly Firth,

when Malcolm was totally defeated, and, according to some

accounts, slain. Others state that he escaped by flight, and

died the following year. Thorfinn thereafter conquered the whole

of Scotland, all the way south to Fife. He then returned to his

ships.

The only

portion of the territory of the northern Picts that had not been

subjected to his power was the district of Athole and the

greater part of Argyle, and here the Scots, on the death of

Malcolm, sought for a king; Duncan, the son of Crinan, abbot of

Dunkeld, and grandson of Malcolm II., being raised to the vacant

throne.

MALCOLM III. Better known in history

by the name of Malcolm Cean Mor, or great head, was the elder of

the two sons of Duncan, king of Scots, by his queen, a sister of

Siward, earl of Northumberland. He was born about 1024, before

his father was called to the throne, and, when the latter in

1039, after a reign of six years, was assassinated by Macbeth,

Malcolm, then only fifteen years of age, fled to Cumberland,

whilst his brother, Donald Bane, took refuge in the Hebrides.

On the

accession of Edward the Confessor to the throne of England in

1043, Malcolm was placed by his father-in-law Siward, under his

protection, when he became a resident at the English court. In

his absence various attempts were made by his adherents in

Scotland to dispossess Macbeth of the throne, in one of which

Malcolm’s grandfather, the aged Crinan, abbot of Dunkeld, was

slain in 1045. Nine years thereafter, namely in 1054, Malcolm

obtained from Edward the assistance of an Anglo-Saxon army,

under the command of Earl Siward, to support his claims to the

crown. This force he accompanied into Scotland, and a furious

battle is said to have ensued, in which Macbeth lost 3,000 men,

and the Anglo-Saxons 1,500, including Osbert, the son of Siward.

Macbeth fled northwards, leaving Lothian in possession of Siward,

who placed Malcolm as king over that district, where the Saxon

influence prevailed. Supported, however, by the Celtic

inhabitants of the north of Scotland, and by the Norwegians of

the districts under the sway of Thorfinn, the powerful earl of

Orkney, Macbeth was still enabled to retain possession of the

throne.

In 1056,

another English army was sent to the assistance of Malcolm. At

this time Thorfinn, and the son of the king of Norway, had gone

to the south, with the strength of the Norwegian power in

Scotland, to attempt the subjugation of England, but, according

to the Irish annals, “God was against them in that affair,” and

their fleet was dispersed in a storm. Macbeth, deprived of

Thorfinn’s aid, was not able to withstand this new array against

him. He was driven north to Lumphanan in Aberdeenshire, where he

was overtaken and slain, December 5th, 1056. The attempt of his

stepson, Lulach, to succeed him on the throne, was, after a

struggle of four months, put an end to by his defeat and death

at Essie in Strathbogie, on the 25th of the following April.

Malcolm was

soon after crowned at Scone. Except the territories possessed by

Thorfinn, consisting, besides Orkney and the Hebrides, of the

nine districts or earldoms of Caithness, Ness, Sutherland, Ross,

Moray, Garmoran, Buchan, Mar, and Angus, he was master of all

the rest of Scotland. His first care was to recompense those who

had supported him in his struggle for the crown. His next, to

recover those northern districts which still remained under

Norwegian rule. The most remarkable reward which he bestowed was

on Macduff, maormor of Fife. The titles of earl and thane which

Malcolm is said to have introduced, were not known in Scotland

till after the Saxon colonization in Edgar’s time, the Norwegian

title iarl being confined to the Orkneys and to Caithness.

Shakspere’s

immortal tragedy of Macbeth, founded on the fables of Boece and

the traditions of the times, has thrown an interest round the

character of the principal personages concerned in it, which

could never have been created by the facts of sober history; but

there is sufficient in the events of Malcolm’s reign to render

it one of the most important in our annals. Gratitude to the

king of England, as well as the unsettled state of his own

kingdom, led Malcolm to cultivate the alliance of Edward the

Confessor, and he paid that monarch a visit in 1059. He had

contracted an intimate friendship with Tostig, who had been

created earl of Northumberland. He was the son of the celebrated

Earl Godwin and brother of Harold, the last king of Saxon

England. They were for a time esteemed “sworn brothers,” but a

quarrel having taken place between them in 1061, Malcolm made a

hostile incursion into Northumberland, and after laying that

country waste, he even violated the peace of St. Cuthbert, in

Holy Island.

On the death of

Thorfinn in 1064, his Norwegian kingdom in Scotland, which had

lasted thirty years, fell to pieces, and the different districts

he had conquered reverted to their native chiefs, “who were

territorially born to rule over them,” (Orkneyinga Saga).

Malcolm married Thorfinn’s widow, Ingioborge, and by her he had

a son, Duncan II. This marriage, however, does not seem in the

slightest to have advanced his interests in the north. The

chiefs of the districts formerly in subjection to the Norwegians

refused to acknowledge his sovereignty, and chose a king for

themselves, Donald, the son of Malcolm, maormor of Moray, and

king of Scotland. It took Malcolm twenty-one years to reduce the

northern districts under his dominion. In 1070, he is said to

have obtained a victory over his opponents, but it was not

decisive. In 1077, as the Saxon Chronicle informs us, he

overthrew Maolsuechtan, maormor of Moray, the son of Lulach, and

in 1085 he got rid of both his rivals by death. The Irish annals

say that in that year, “Malsnectai, son of Lulach, king of

Moray, died peacefully. Donald, son of Malcolm, king of Alban,

died a violent death.”

Long previous

to this, however, events in connexion with England had occurred

which exercised an important influence on his reign, and which

may now be briefly detailed. Edward the Confessor died 5th

January 1066, and was succeeded by Harold. Tostig, the brother

of the latter, had, from his extortions and his violence, so

irritated the people of Northumberland, that they rose against

him and drove him from his earldom. This happened a few years

previous to the death of Edward the English king. Harold found

it prudent to abandon his brother’s cause, on which Tostig

became his bitterest enemy. He first took refuge in Flanders,

with Baldwin, his father-in-law, and afterwards visited William,

duke of Normandy. On Harold’s accession, he collected about

sixty vessels in the ports of Flanders, and committed some

depredations on the south and east coasts of England. He next

sailed to Northumberland, and was there joined by Harold

Halfager, by some called Hadrada, king of Norway, with 300 sail.

Entering the Humber, they disembarked the troops, but were

defeated and put to flight, when Tostig proceeded into Scotland.

It is now known whether Malcolm received him at his court, or

aided, or countenanced in any way, his projects against his

brother, the new king of England. Lord Hailes thinks it probable

that he was not received by Malcolm, but only remained at anchor

in some Scottish bay, with the remains of his fleet, till joined

by reinforcements from Norway. On receiving these he and Hadrada

again invaded England, and were both slain at the battle of

Stamford Bridge, 25th September 1066. The battle of Hastings

took place on the 14th of the following October, when Harold was

killed and William the Conqueror became king of England.

Two years

thereafter, Edgar Atheling, grandson of Edmund Ironside, and the

heir of the Saxon line, with his mother, the princess Agatha,

and his two sisters, Margaret and Christina, arrived in

Scotland. In their train came many Anglo-Saxons, and among them

Gospatrick and other nobles of Northumberland. Some authors say

that it was their intention to proceed to Hungary, the native

country of Edgar and his two sisters, when they were driven by a

storm into the firth of Forth. Malcolm then resided at the tower

which still bears his name, on the small peninsular mount, in

the glen of Pittencrieff, near Dunfermline, in Fifeshire. On

hearing of the arrival of the illustrious strangers, he hastened

to invite them to his royal tower. There they were hospitably

entertained, and as he was at this time a widower, there his

nuptials with the princess Margaret were, soon after, celebrated

with unwonted splendour.

Margaret was

one of the most pious and accomplished princesses of her day,

and her character and influence tended much to improve and

refine the rude manners of her husband’s subjects. On her

husband himself her virtues and gentleness exercised a most

salutary power. We learn from Turgot, her confessor and

biographer, that Malcolm liked and disliked whatever she did,

and that such was his veneration for her worth and piety, that

being unable to read, he was in the habit of kissing her missals

and prayer-books, which, in token of his devotion, he caused to

be splendidly bound and adorned with gold and precious stones.

She persuaded him to pass the night in fervent prayer, much to

the astonishment of his courtiers. “I must acknowledge,” adds

Turgot, “that I often admired the works of the divine mercy,

when I saw a king so religious, and such signs of deep

compunction in a laic.”

Into the court

of Malcolm she introduced unusual splendour. She encouraged the

importation of rich dresses of various colours for himself and

his nobles, which led to the commencement of a trading

intercourse with foreign countries, and to this reign may be

assigned the introduction of the wearing of tartan, which came

afterwards to distinguish the clans. In her own attire she was

magnificent, and she increased the number of attendants on the

person of the king. Under her guidance the public appearances of

the sovereign were attended with more parade and ceremony than

had ever previously been the case. She also caused the king to

be served at table in gold and silver plate; “at least,” says

Turgot, afraid of going beyond the truth, “the dishes and

vessels were gilt or silvered over.”

Malcolm seems

to have intrusted the care of matters respecting religion and

the internal polity of the kingdom, entirely to her. Anxious for

the reformation of the church, she held frequent conferences

with the clergy. On one of the occasions the proper season for

celebrating Lent was the subject of discussion between them. The

clergy knew no language but the Gaelic, and the king, who had

spend fifteen years in England, and understood the Saxon as well

as his own native language, acted as interpreter. “Three days,”

says Turgot, “did she employ the sword of the Spirit in

combating their errors. She seemed another St. Helena out of the

Scriptures convincing the Jews.” At last the clergy yielded to

her views. She was also the means of inducing them to restore

the celebration of the Lord’s supper, which had fallen into

disuse, and of keeping sacred the Sabbath, which was scarcely

distinguishable from any other day of the week.

Malcolm

espoused the cause of his brother-in-law with great ardour. In

September 1069, with the assistance of the Danes, and

accompanied by Edgar Atheling, the Anglo-Saxon and Northumbrian

nobles, led by Gospatrick, invaded England, and having taken the

castle of York by storm, they put the Norman garrison to the

sword. Instead, however, of following up their success, the

Northumbrians departed to their own territory, while the Danes

retired to their ships. The secret of this change in their

proceedings was that William had gained over Gospatrick, by

conferring on him the earldom of Northumberland, and had bribed

Osborne the Danish commander, to quit the English shores. Edgar

Atheling and his few remaining adherents were, in consequence,

obliged to retreat to Scotland.

The following

year, Malcolm led a numerous army into England, by the western

borders, through Cumberland. If it had been intended that he was

to support the movements of Edgar, and his Danish and

Northumbrian allies, he came too late. Nevertheless, his

operations were energetic enough. After wasting Teesdale, he

defeated an Anglo-Norman army that attempted to oppose his

progress, at a place called Hinderskell, penetrated into

Cleveland, and thence advanced into the eastern parts of the

diocese of Durham, spreading desolation and dismay wherever he

appeared. He spared neither age nor sex, and even the churches,

with those who had taken refuge in them, were burnt to the

ground. While thus engaged, he received intelligence that his

own territory of Cumberland was laid waste by Gospatrick, who,

as already stated, had gone over to King William’s interest.

On his return,

Malcolm led captive into Scotland such a multitude of young men

and women, that, says the English historian, Simeon of Durham,

“for many years they were to be found in every Scottish village,

nay, even in every Scottish hovel.” In 1072, William retaliated

by invading Scotland both by land and sea. He penetrated as far

as the Firth of Forth, but finding the conquest of Scotland not

so easy a task as had been that of England, a peace was

concluded at Abernethy, the old Pictish capital, when Malcolm

consented, in accordance with the feudal custom of the Normans,

to do homage for the lands which he held in England. Among the

hostages which he gave on this occasion was his eldest son,

Duncan, who thus had the benefit of living many years under the

Norman monarchs of England. By this peace, Malcolm, in a manner,

abandoned the cause of his weak-minded brother-in-law, Edgar

Atheling, and that personage, after making his peace with the

English monarch, received from him a handsome pension, and went

to reside at Rouen in Normandy.

With Edgar

Atheling, Malcolm had refused to give up to the English king,

the exiled nobles and others who had taken refuge in Scotland.

With the double view of strengthening his power by the influx of

so many brave and skilful strangers, and of benefiting his

subjects by the introduction among them of those who possessed a

higher civilization than, in their rude and unsettled state,

they had even known, he even encouraged them to come into his

kingdom. Among them were persons of Norman as well as of

Anglo-Saxon lineage, who had fled from the exactions and tyranny

of the Conqueror, or had been refused promised rewards for their

services. Malcolm received and welcomed them all, and to these

Norman knights and adventurers who thus came flocking across the

border, he gave lands and heritages, to induce them to remain.

They thus became the progenitors of many of our noble families.

Thousands of the poorer English, too, to escape the grinding

oppressions of their Norman rulers, sought a refuge in Scotland,

some even selling themselves for slaves, to obtain a

subsistence.

Gospatrick,

having incurred the suspicions of William, was deprived of the

earldom of Northumberland, and returning into Scotland,

succeeded in being reconciled to Malcolm, from whom he obtained

the manor of Dunbar, and other lands in the Merse and Lothian.

He was the ancestor of the earls of Dunbar and March. In 1079,

in the absence of William in Normandy, Malcolm again invaded

Northumberland, and wasted the country as far as the river Tyne.

The following year, Robert, the eldest son of William, entered

Scotland, but was obliged to retreat. To check the incursions of

the Scots into England, he erected a fortress near the Tyne, at

a place called Moncaster or Monkchester, from its being the

residence of monks, but the name of which was thereafter in

consequence changed to Newcastle.

At the request

of his queen, who has been canonized in the Romish Calendar as

St. Margaret, and of her confessor, Turgot, Malcolm founded and

endowed a monastery, in the vicinity of his residence, for

thirteen Culdees, which, with its church or chapel, was

dedicated to the Holy Trinity. This was the origin of the abbey

of Dunfermline.

The latter

portion of Malcolm’s reign was occupied in a struggle with

William Rufus, the son and successor of the Conqueror on the

throne of England. Cumberland and his other English possessions

having been withheld from him by the English king, Malcolm,

assembling his forces, broke across the borders, in May 1091,

when he penetrated as far as Chester, on the Wear; but on the

approach of the English, with a superior force, he prudently

retreated without hazarding a battle, and thus secured his booty

and his captives. In the autumn of the same year, Rufus led a

numerous army into Scotland. Malcolm advanced to meet him. By

the intercession, however, of Edgar Atheling, who accompanied

the Scottish army, and of Robert, duke of Normandy, the eldest

brother of the English king, a peace was concluded, without the

risk of a battle, Rufus consenting to restore to Malcolm twelve

manors in England which he had held under the Conqueror, and to

make an annual payment to him of twelve marks of gold, and

Malcolm, on his part, agreeing to do homage for the same, under

the same tenure of feudal service as before.

In 1092,

William Rufus began to fortify the city of Carlisle and to build

a castle there. As this was an encroachment on Malcolm’s

territory of Cumberland he remonstrated against it, when the

English king proposed a personal interview on the subject.

Malcolm, in consequence, proceeded to Gloucester, 24th August

1093. As a preliminary measure, Rufus required him again to do

homage to him there, in presence of the English barons. This

Malcolm absolutely refused, but although he had done homage to

Rufus for his English lands not much above a year before at

Abernethy, he now offered to do it, as formerly had been the

custom, on the frontiers of the two kingdoms, and in presence of

the chief men of both. Some of his councilors advised Rufus to

detain the Scottish king, now that he had him in his power, till

he had complied with his request; but although he had the grace

to reject this base proposal, it was with the most unkingly

contumely that he dismissed him from his court. Malcolm returned

home, burning with indignation and vowing revenge, and hastily

assembling a tumultuous and undisciplined army, he burst into

Northumberland, which he wasted, then, sweeping onwards to

Alnwick, he laid siege to the castle. He had not been many days

there, however, before he was surprised by Robert de Moubray, at

the head of a strong Norman and English force3. A fierce

engagement ensued, when Malcolm was slain, with his eldest son.

This fatal fight took place 13th November 1093. Malcolm’s fourth

son, Edgar, who was also in the battle, escaped, and three days

after reached the castle of Edinburgh, where his mother lay

dying. On his appearance, she in a faint voice eagerly enquired,

“How fares it with your father, and your brother, Edward?” The

youth was silent. “I know all,” she cried; “I adjure you by this

holy cross, and by your filial affection, that you tell me the

truth.” He answered, “your husband and your son are both slain.”

Raising her eyes and hands to heaven, the dying queen said,

“Praise and blessing be to thee, Almighty God, that thou hast

been pleased to make me endure so bitter anguish in the hour of

my departure, thereby, as I trust, to purify me, in some

measure, from the corruption of my sins. And thou, Lord Jesus

Christ, who, through the will of the Father, hast enlivened the

world by thy death, O deliver me!” and straightway expired. So

great was the benevolence of this truly excellent princess that

she secretly paid the ransom of many of her Saxon countrymen in

bondage in Scotland, when she found their condition too grievous

to be borne.

The character

of Malcolm Canmore is that of an able, wise, and energetic

monarch, who, after subjecting to his sovereignty the various

rude and discordant tribes that inhabited his kingdom, was

successful in maintaining its independence unimpaired during a

long reign of 37 years, and that against two such formidable

opponents as William the Conqueror and his son, William Rufus.

As an instance of his personal intrepidity the following

incident is related: Having received intelligence that one of

his nobles had formed a design against his life, he took an

opportunity, when out hunting, of leading him into a solitary

place, then, unsheathing his sword, he said, “Here we are alone,

and armed alike. You seek my life. Take it.” The astonished

noble, overcome by this address, threw himself at the feet of

the king, and implored his clemency, which was readily granted.

The removal of

his court from Abernethy to Dunfermline, about the year 1063,

and the encouragement which, after the Norman conquest of

England and his marriage with Queen Margaret, he gave to the

immigration of Anglo-Saxons and Norman adventurers into the

kingdom, had the effect of causing the Gaelic population to

retire inland from the plains, and to divide themselves into

clans and tribes, with the institution of separate chiefs, and

the preservation of all those feelings and usages which long

kept them a peculiar and distinct race from the other

inhabitants of Scotland. In the reign of Malcolm Canmore, the

whole of the country south of the Forth was possessed by the

Scots, and those who spoke the Saxon language, while the Celtic

portion of the nation occupied the remaining districts.

Tenacious of their native language and ancient customs, the

latter viewed with equal scorn and disgust the introduction of

foreign manners and races into the kingdom, and hence began that

long struggle between the Scottish and Celtic communities which

lasted for nearly seven hundred years, and was only terminated

on the field of Culloden in 1746. “The people,” says General

Stewart of Garth, referring to the Gaelic inhabitants (sketches,

vol. i. p. 20), “now beyond the reach of the laws, became

turbulent and fierce, revenging in person those wrongs for which

the administrators of the laws were too distant and too feeble

to afford redress. Thence arose the institution of chiefs, who

naturally became the judges and arbiters in the quarrels of

their clansmen and followers, and who were surrounded by men

devoted to the defence of their rights, their property, and

their power; and accordingly the chiefs established within their

own territories a jurisdiction almost wholly independent of

their liege lord.”

Malcolm had by

his queen, Margaret, six sons and two daughters. The sons were,

Edward, who was slain with his father near Alnwick; Ethelred,

who was bred a churchman and became Culdee abbot of Dunkeld;

Edmund; Edgar, Alexander, and David. The three last were

successively kings of Scotland. The elder daughter, Maud,

married Henry I. of England, a marriage which united the Saxon

and the Norman dynasties, and Mary, the younger, became the wife

of Eustace, count of Boulogne.

MALCOLM IV., King of Scots, born in

1141, was the son of Prince Henry, son of David I., and

succeeded his grandfather, May 24, 1153, a year after his

father’s death, being then only twelve years old. The same year

he was crowned at Scone. He acquired the name of Malcolm the

Maiden, either from the effeminate expression of his features,

or from the softness of his disposition. In the following

November, Somerled, thane of Argyle, invaded the Scottish

coasts, at the head of all the fierce tribes of the isles. The

accession of a new king, and he a mere boy, appears to have been

deemed by this formidable chief a favourable time to endeavour

to advance the cause of his grandsons, the sons of the monk

Wimond, otherwise Malcolm MacHeth, who claimed the earldom of

Moray, and who had been imprisoned in Roxburgh castle by David

I. as an impostor. In 1156, Donald, a son of Wimond, was

discovered skulking at Whithorn in Galloway, and sent to share

the captivity of his father. After harassing the country for

some years, Somerled was at last forced back to his own

territories, by Gilchrist, earl of Angus, and a treaty of peace

was concluded with him in 1157, which was considered of so much

importance at the time as to form an epoch in the dating of

Scottish charters.

Malcolm had no

sooner accommodated matters with Somerled, than a demand was

made upon him by Henry I. of England, for those parts of the

English territory which the Scottish kings held in that kingdom.

On this account Malcolm had an interview with Henry at Chester,

when he did homage to him for the same, as his predecessors had

done, “reserving all his dignities.” Malcolm was then only

sixteen years of age, and Henry, taking advantage of his

inexperience, easily prevailed upon the youthful monarch, to

surrender to him Cumberland and Northumberland, at the same time

bestowing upon him the earldom of Huntington. Fordun says that

the English king had, on this occasion, corrupted his

councilors.

In 1158,

desirous of obtaining the honour of knighthood from the king of

England, Malcolm repaired to Henry’s court at Carlisle, for the

purpose, but Henry refused to bestow upon him an honour,

probably on account of his youth, which was highly prized in

that age, and Malcolm returned home greatly disappointed. In the

following year, Malcolm passed over to France, where the English

monarch then was, and after serving under his banner he was at

length knighted by him. The Scots, indignant at his subservience

to Henry, and apprehensive that he would become the mere vassal

of England, sent a deputation to remonstrate with Malcolm on his

conduct. “We will not,” said they, “have Henry to rule over us.”

Malcolm, in consequence, hastened back to Scotland, and on his

arrival assembled a parliament at Perth.

The fierce

nobles who, as governors of their respective provinces, were

bound to maintain the independence of the kingdom, availed

themselves of this opportunity to attempt to seize the king’s

person. Accordingly, Ferquhard, earl of Strathearn, and five

other earls assaulted the tower in which Malcolm had taken

refuge, but were repulsed. On the interference of the clergy, a

reconciliation took place between the young king and his

offended nobles.

Fortunately for

Malcolm an occasion almost immediately occurred to give

employment to them and their followers. Fergus, lord of

Galloway, the most potent feudatory of the Scottish crown, and

the son-in-law of Henry I., threw off his allegiance, and

stirred up an insurrection against Malcolm. At the head of a

powerful army, the king entered Galloway, and though twice

driven back, he at length succeeded, in 1160, in overpowering

its rebellious lord. He then compelled Fergus to resign his

lordship, and to give his son, Uchtred, as an hostage for the

peace concluded between them; after which Fergus retired to the

abbey of Holyrood, where he died of a broken heart.

In 1161, a

still more formidable insurrection broke out among the

inhabitants of the province of Moray, which comprehended all

what is now Elginshire, all Nairnshire, a considerable part of

Banffshire, and the half of continental Inverness-shire. The

pretext was the attempt on Malcolm’s part to intrude the

Anglo-Norman jurisdiction upon their Celtic customs, and the

settling of Flemish colonists among them. The men of Moray were

never wanting in an excuse for rising in arms. They were the

most unruly and rebellious of all the subjects of the sovereigns

of Scotland. According to Fordun, “no solatiums or largesses

could allure, or treaties or oaths bind them to their duty.” On

this occasion the insurgents laid waste the neighbouring

counties, and so regardless were they of the royal authority

that they actually hanged the heralds who were sent to summon

them to lay down their arms. Malcolm dispatched against them a

strong force under that Earl Gilchrist who had been sent against

Somerled, but he was routed, and forced to recross the

Grampians.

This defeat

roused all the energy of Malcolm’s character, and with the whole

array of the kingdom he marched against them. He found them

assembled on the muir of Urquhart, near the Spey, ready to give

him battle. After crossing that river, Malcolm’s nobles, seeing

their strength, advised him to negotiate with the rebels, and to

promise them that if they submitted, their lives would be

spared. The Moraymen accepted the offer, the king kept his word,

and now occurred the extraordinary circumstance of different

parts of the country exchanging their populations. To put an

end, at once and for ever, to the frequent insurrections which

occurred in the province, Malcolm ordained that all who had been

engaged in the rebellion should remove out of Moray, and that

their places should be supplied with people from other parts of

the kingdom. In consequence, some transplanted themselves into

the northern, but the greater number into the southern

districts, as far as Galloway. The older historians say that the

Moraymen were almost totally cut off in an obstinate battle, and

strangers put in their place, but this statement is at variance

with the register of Paisley. Among the new families brought in

to replace those who were removed, the principal were the

powerful earls of Fife and Strathearn, with the Comyns and

Bissets, and among those who remained were the Inneses, the

Calders and others. After thus removing the rebels, and

colonizing the province with a quieter race, Malcolm, as well as

his successor, William the Lion, appear to have frequently

resided in Moray, for from Inverness, Elgin, and various other

of its localities, several of their charters are dated.

In July 1163,

Malcolm did homage to the king of England and his infant son at

Woodstock. The following year he founded and richly endowed an

abbey for Cistertian monks at Coupar-Angus. He had previously,

in 1156, founded the priory of Emanuel near Linlithgow, for nuns

of the same order.

In 1164,

Somerled, the ambitious and powerful lord of the Isles, made

another and a last attempt to overthrow the king’s authority.

Assembling a numerous army from Argyle, Ireland, and the Isles,

he sailed up the Clyde with 160 galleys, and landed his forces

near Renfrew, threatening, as some of the old chroniclers inform

us, to make a conquest of the whole of Scotland. Here, according

to the usual accounts, he was slain, with his son, Gillecolane,

after a battle, in which he was defeated by an inferior force of

the Scots. Tradition, however, states that he was assassinated

in his tent by an individual in whom he placed confidence, and

that his followers, deprived of their leader, hastened back to

the Isles, without hazarding an engagement.

Malcolm died at

Jedburgh, of a lingering disease, December 9, 1165, at the early

age of 24, and was succeeded by his brother William, styled

William the Lion.

MALCOLM, SIR PULTENEY, a distinguished

naval officer, an elder brother of Sir John Malcolm, the subject

of the following notice, was born at Douglan, near Langholm,

Dumfries-shire, February 20, 1768. His father, George Malcolm,

farmer, Burnfoot, had, by his wife, the daughter of James Pasley,

Esq. of Craig and Burn, 17 children. Robert, the eldest son, at

his death was high in the civil service of the East India

Company; James, Pulteney, and John, the next three sons, were

honoured with the insignia of knights commanders of the Bath at

the same time, the former for his distinguished services in

Spain and North America, when commanding a battalion of royal

marines, and Sir John, for his military and diplomatic services

in India. The younger sons were Gilbert, rector of Todenham;

David, in a commercial house in India; and Admiral Sir Charles

Malcolm, of whom a memoir is given below.

Pulteney

entered the navy, October 20, 1778, as a midshipman on board the

Sybille frigate, commanded by his maternal uncle, Captain Pasley,

with whom he sailed to the Cape of Good Hope; and on his return

thence, removed with him into the Jupiter, of which he was

appointed lieutenant in March 1783. At the commencement of the

French revolutionary war, he was first lieutenant of the

Penelope at Jamaica; in which ship he assisted at the capture of

the Inconstante frigate, and Gaelon corvette, both of which he

conducted to Port Royal in safety. He also commanded the boats

of the Penelope in several severe conflicts, and succeeded in

cutting out many vessels from the ports of St. Domingo. In April

1794 he was made a commander, when he joined the Jack Tar; and

upon Cape Nichola Mole being taken possession of by the British,

he had the direction of the seamen and marines landed to

garrison that place. In October 1794 he was promoted to the rank

of post captain, and the following month was appointed to the

Fox frigate, with which he subsequently served in the North Sea.

Having proceeded with a convoy to the East Indies, he captured

on that station La Modeste, of 20 guns. In 1797 the duke of

Wellington, then Colonel Wellesley, of the 33d regiment, took a

passage with Captain Malcolm, in the Fox, from the Cape of Good

Hope to Bengal. He afterwards served in the Suffolk, the

Victorious, and the Royal Sovereign; and in March 1805 was

appointed to the Donegal, in which he accompanied Lord Nelson in

the memorable pursuit of the combined squadrons of France and

Spain to the West Indies.

On his return

to the Channel, Captain Malcolm was sent to reinforce Admiral

Collingwood off Cadiz. Four days previous to the battle of

Trafalgar, the Donegal, being short of water, and greatly in

need of a refit, was ordered to Gibraltar. On the 20th October

Captain Malcolm received information that the enemy’s fleets

were quitting Cadiz. His ship was then in the Mole nearly

dismantled, but by the greatest exertions he succeeded in

getting her out before night, and on the 23d joined Admiral

Collingwood in time to capture El Rayo, a Spanish three-decker.

Towards the close of 1805 the Donegal accompanied Sir John

Duckworth to the West Indies, in quest of a French squadron that

had sailed for that quarter; and in the battle fought off St.

Domingo, February 6, 1806, Captain Malcolm greatly distinguished

himself. On his return to England, he was honoured with a gold

medal for his conduct in the action, and, in common with the

other officers of the squadron, received the thanks of both

houses of parliament.

In the summer

of 1808 he escorted the army under General Wellesley from Cork

to Portugal, and for his exertions in disembarking the troops,

he received the thanks of Sir John Moore and Sir Arthur

Wellesley. The Donegal was subsequently attached to the Channel

fleet under the orders of Sir John Gambier; and after the

discomfiture of the French ships in Aix Roads in April 1809,

Captain Malcolm was sent with a squadron on a cruise. He next

commanded the blockade of Cherbourg, on which station the ships

under his orders captured a number of privateers, and on one

occasion drove two frigates on shore near Cape La Hogue. In 1811

the Donegal was paid off, when Captain Malcolm was appointed to

the Royal Oak, a new 74, in which he continued off Cherbourg

until March 1812, when he removed into the San Josef, 110 guns,

as captain of the Channel fleet under Lord Keith. In the

subsequent August he was promoted to the rank of colonel of

marines, and December 4, 1813, was appointed rear-admiral. In

June 1814 he hoisted his flag in the Royal Oak, and proceeded to

North America with a body of troops, under Brigadier-general

Ross. Soon after his arrival, he accompanied Sir Alexander

Cochrane on an expedition up the Chesapeake, when the duty of

regulating the collection, embarkation, and re-embarkation of

the troops employed against Washington, Baltimore, and New

Orleans, devolving upon him, he performed it in a manner that

obtained the warmest acknowledgments of the commander-in-chief.

He was afterwards employed at the siege of Fort Boyer, on Mobile

Point, the surrender of which, by capitulation, on February 14,

terminated the war between Great Britain and the United States.

At the

extension of the order of the Bath into three classes, January

2, 1815, Admiral Malcolm was nominated, with his two brothers, a

knight commander. After his arrival in England, on the renewal

of hostilities with France, in consequence of the return of

Napoleon from Elba, he was appointed commander-in-chief of the

naval force ordered to co-operate with the duke of Wellington

and the allied armies, on which service he continued until after

the restoration of the bourbons. His last appointment was to the

important office of commander-in-chief on the St. Helena

station, where he continued from the spring of 1816 until the

end of 1817. By the cordiality of his disposition and manners,

he not only obtained the confidence, but won the regard of the

emperor Napoleon. “Ah! There is a man,” he exclaimed in

reference to Sir Pulteney Malcolm, “with a countenance really

pleasing; open, frank, and sincere. There is the face of an

Englishman – his countenance bespeaks his heart; and I am sure

he is a good man. I never yet beheld a man of whom I so

immediately formed a good opinion as of that fine soldier-like

old man. He carries his head erect, and speaks out openly and

boldly what he thinks, without being afraid to look you in the

face at the time. His physiognomy would make every person

desirous of a further acquaintance, and render the most

suspicious confident in him.” One day when fretting at the

unjust treatment he received, he exclaimed to the admiral, “Does

your government mean to detain me upon this rock until my

death’s day?” Sir Pulteney replied, “Such I apprehend is their

purpose.” “Then the term of my life will soon arrive,” said

Napoleon. “I hope not, Sir,” answered Sir Pulteney, “I hope you

will survive to record your great actions, which are so

numerous, and the task will insure you a term of long life.”

Napoleon felt the compliment and acknowledged it by a bow, and

soon recovered his good humour. On his deathbed he paid a

well-merited tribute to the generosity and benevolence of Sir

Pulteney, whose conduct at St. Helena is described by Sir

Walter Scott in his ‘Life of Napoleon,’ in a manner highly

honourable to him. He was advanced to the rank of vice-admiral

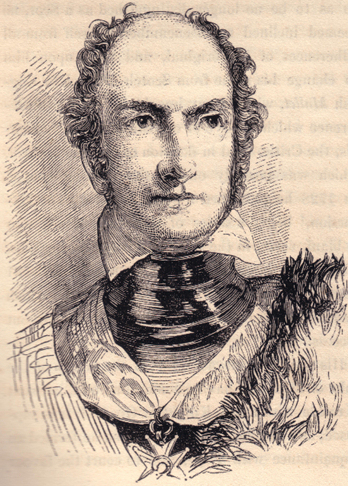

July 19, 1821, and of admiral January 10, 1837. He died July 20,

1838. a monument has been erected to his memory. Subjoined is

his portrait:

[portrait of Sir Pulteney Malcolm]

Sir Pulteney

Malcolm married, January 18, 1809, Clementina, eldest daughter

of the Hon. W. F. Elphinstone.

MALCOLM, SIR JOHN, a distinguished

soldier and diplomatist, a younger brother of the subject of the

foregoing memoir, was born May 2, 1769, on the farm of Burnfoot,

near Langholm, in Dumfries-shire. In 1782 he went out to the

East Indies as a cadet in the Company’s service. On his arrival

he was placed under the care of his uncle, Dr. Gilbert Pasley,

and assiduously applied himself to the study of the manners and

languages of the East. The abilities which he displayed at the

siege of Seringapatam, in 1792, attracted the notice of Lord

Cornwallis, who appointed him Persian interpreter to a body of

British troops in the service of one of the native princes. In

1794, in consequence of bad heath, he revisited his native

country; but the following year he returned to India on the

staff of Field-marshal Sir Alured Clarke; and for his conduct at

the taking of the Cape of Good Hope, he received the public

thanks of that officer. In 1797 he obtained a captain’s

commission. In 1799 he was ordered to join the Nizam’s

contingent force in the war against Tippoo Saib, with the chief

command of the infantry, in which post he continued till the

surrender of Seringapatam, where he highly distinguished

himself. He was then appointed joint secretary, with Captain,

afterwards Sir Thomas Munro, to the commissioners for settling

the new government of Mysore. In the same year he was sent by

Lord Wellesley on a diplomatic mission to Persia, a country

which no British ambassador had visited since the reign of Queen

Elizabeth.

Captain Malcolm

returned to Bombay in 1801, when he was appointed private

secretary to the governor-general, who stated to the secret

committee that “he had succeeded in establishing a connection

with the actual government of the Persian empire, which promised

to British natives in India political and commercial advantages

of the most important description.” In January 1802 he was

promoted to the rank of major; and on the death of the Persian

ambassador, who was accidentally shot at Bombay, he was again

sent to Persia to make the necessary arrangements for the

renewal of the embassy. In February 1803 he was appointed

Resident with the rajah of Mysore; and in December 1804 he

attained the rank of lieutenant-colonel. In June 1805 he was

nominated chief agent of the governor-general, in which capacity

he continued to act till March 1806, during which period he

concluded several important treaties with native princes.

On the arrival

in India, in April 1808, of the new governor-general, Lord Minto,

he dispatched Colonel Malcolm on a mission to Persia, with the

view of endeavouring to counteract the designs of Napoleon, who

then threatened an invasion of India from that quarter. In this

difficult embassy, however, he did not wholly succeed. He

returned in the following august, and soon after proceeded to

his residency at Mysore. Early in 1810, owing to a change in the

policy of the Persian court, he was again appointed ambassador

to Persia, where he remained till the nomination of Sir Gore

Ouseley as minister plenipotentiary. On his departure the shah

conferred upon him the order of the Sun and Lion, presented him

with a valuable sword, and made him a khan and sepahdar of the

empire.

In 1812 Colonel

Malcolm again visited England, and soon after his arrival

received the honour of knighthood. The same year he published,

in one volume, ‘A Sketch of the Sikhs, a singular Nation in the

province of the Punjaub, in India.’ In 1815 appeared his

‘History of Persia,’ in 2 vols. 4to, which is valuable from the

information it contains, taken from oriental sources, regarding

the religion, government, manners, and customs of the

inhabitants of that country, in ancient as well as in modern

times. He returned to India in 1817, and on his arrival was

attached, as political agent of the governor-general, to the

force under Sir Thomas Hislop in the Deccan. With the rank of

brigadier-general, he was appointed to the command of the third

division of the army, and greatly distinguished himself in the

decisive battle of Mehidpoor, when the army under Mulhar Rao

Holkar was completely routed. For his skill and valour on this

occasion he received the thanks of the house of commons, on the

motion of Mr. Canning, who declared that “the name of this

gallant officer will be remembered in India as long as the

British flag is hoisted in that country.” His conduct was also

noticed by the prince regent, who expressed his regret that the

circumstance of his not having attained the rank of

major-general prevented his being then created a knight grand

cross, which honour, however, was conferred on him in 1821.

After the

termination of the war with the Mahrattas and Pindarries, he

received the military and political command of Malwa, and

succeeded in establishing the Company’s authority, both in that

province and the other territories adjacent, which had been

ceded to them.

In April 1822

he returned once more to Britain with the rank of major-general.

Shortly after, he was presented by the officers who had acted

under him in the late war with a superb vase, valued at £1,500.

The court of directors of the East India company likewise

testified their sense of his merits by a grant to him of £1,000

a-year. In July 1827 he was appointed governor of Bombay, which

important post he resigned in 1831, and finally returned to

Britain. On quitting India, he received many gratifying

instances of the esteem and high consideration in which he was

held. The principal European gentlemen of Bombay requested him

to sit for his statue, which was executed by Chantrey, and

erected in that city; the members of the Asiatic Society

requested a bust of him for their library; the native gentlemen

of Bombay solicited his portrait, to be placed in the public

room; the East India Amelioration Society voted him a service of

plate; and the United society of Missionaries, including

English, Scots, and Americans, acknowledged with gratitude the

assistance they had received from him in the prosecution of

their pious labours.

Subjoined is

Sir John Malcolm’s portrait:

[portrait of Sir John Malcolm]

Soon after his

arrival in England in 1831, he was elected M.P. for Launceston,

and took an active part in the proceedings in the house of

commons upon several important questions, particularly the

Scottish reform bill, which he warmly opposed. After the

dissolution of parliament in 1832 he offered himself for

Carlisle, but being unsuccessful, he retired to his seat near

Windsor, and employed himself in writing a Treatise upon ‘The

Government of India,’ with the view of elucidating the difficult

questions relating to the renewal of the East India Company’s

charter, which was published only a few weeks previous to his

death. His last address in public was at a meeting in the

Thatched House Tavern, London, for the purpose of forming a

subscription to buy up the mansion of Abbotsford for the family

of the great novelist; and on that occasion his concluding

sentiment was “that when he was gone, his son might be proud to

say that his father had been among the contributors to that

shrine of genius.” On the day following he was struck with

paralysis, and died at London, May 31, 1833. A monument has been

erected to his memory in Westminster Abbey, and also an obelisk,

100 feet high, on Langholm hill, in his native parish of

Westerkirk. He married, in June 1807, charlotte, daughter of Sir

Alexander Campbell, Bart., by whom he had five children.

Sir John Malcolm’s works are:

Sketch of the Political History of India,

from the Introduction of Mr. Pitt’s Bill, A.D. 1784, to the

present date. London, 1811, 8vo.

Sketch of the Sikhs, a nation who inhabit the

provinces of the Punjaub, situated between the rivers Jumna and

Indus in India. London, 1812, 8vo.

Observations on the disturbances in the

Madras Army in 1809; in 2 parts. London, 1812, 8vo.

History of Persia, from the most early period

to the present time, containing an account of the religion,

government, usages, and character of the inhabitants of that

kingdom. London, 1815, 2 vols, 4to.

A memoir of Central India, including Malwa

and adjoining Provinces, with the history and copious

illustrations of the past and present condition of that country.

London, 1823, 2 vols, 8vo.

The Political History of India from 1784 to

1823. Lond., 1826, 2 vols. 8vo.

The Government of India. London, 1833, 8vo.

The Life of Robert, Lord Clive, collected

from the Family Papers, communicated by the earl of Powis.

London, 1836, 3 vols, 8vo. Posthumous.

MALCOLM, SIR CHARLES, an eminent naval

officer, the tenth son of George Malcolm of Burnfoot, and

youngest brother of the preceding, was born at Burnfoot,

Dumfries-shire, in 1782, and entered the navy in 1791, when only

nine years old. In 1798, he was master’s mate of the Fox, of 32

guns, commanded by his brother, Pulteney, when, with the

Sybille, of 38 guns, that ship entered the Spanish harbour of

Manilla, the capital of the Philippines, under French colours,

and in the face of three ships of the line and three frigates,

succeeded in capturing seven boars, taking prisoner 200 men, and

carrying off a large quantity of ammunition and materials of

war. In 1807, he got the command of the Narcissus, 32. On board

this ship he attacked a convoy of 30 sail in the Conquet Roads,

on which occasion he was slightly wounded. In 1809, he assisted

in the capture of Les Saintes, islands in the West Indies. In

June of the same year he was appointed to the Rhine, 38, in

which he actively co-operated with the patriots on the north

coast of Spain.

Subsequently he

served in the West Indies, and on the coast of Brazil. On July

18, 1815, he landed and stormed a fort at Corrigion near

Abervack, which was the last exploit of the kind achieved during

the war. In July 1822, he was nominated to the command of the

William and Mary, royal yacht, lying at Dublin, in attendance on

the lord-lieutenant; and in 1826, to the Royal charlotte, yacht,

on the same service. In 1827 he was knighted by the Marquis

Wellesley, then lord-lieutenant of Ireland. Soon after he was

appointed superintendent of the Bombay marine.

During the ten

years that he held that office, he effected a complete reform in

the administration of the service, and converted its previous

system into that of the Indian navy. He also instituted many

extensive and important surveys, and was prominently concerned

in the establishment of steam navigation in the Red Sea. In 1837

he was promoted to the rank of rear-admiral, and in 1847 to that

of vice-admiral. He died at Brighton, June 14, 1851, aged 69. He