|

MONTROSE, Duke of,

a title in the peerage of Scotland, conferred by James III. on David,

fifth earl of Crawford, by royal charter, dated 18th May, 1488, to

himself and his heirs. On the 19th September 1489, a new patent or

charter, under the great seal, was granted to him by James IV.,

conferring the dukedom upon him for life only. He died at Finhaven at

Christmas 1495, and the dukedom is said to have then become extinct. In

1848 a petition was presented to the queen by the earl of Crawford and

Balcarres, claiming it on the ground of its being vested in the heir

male. This petition was referred to the House of Lords, and the claim

was opposed by the Crown and the duke of Montrose, on the ground that

the charter of 18th May 1488, was annulled by the act of the first year

of the reign of James IV., called the Act Rescissory, and that the grant

of the dukedom, made in 1489, was never registered. After hearing

parties, on Aug. 5, 1853, their lordships adopted a resolution to the

effect that the claimant had not made out his right to the dignity. Soon

after, Lord Lindsay, son of the earl of Crawford and Balcarres,

addressed a letter to the Times newspaper, protesting against the

resolution of the House of Lords, and stating that he had published a

full “Report of the Montrose Claim,” containing, among other documents,

“an Address to her Majesty, in humble remonstrance against the opinion

reported to her Majesty.” Lord Lindsay submits that the principles on

which the decision of the peers is founded are, one and all, wholly

repugnant to the understanding and practice of past times, and to plant

equity and justice. The opinion, he farther asserts, is entitled to less

than usual weight in respect to the unwonted and strange departure from

established forms of procedure – the decision having been given before

the voluminous evidence was ordered to be printed, and the evidence thus

“arbitrarily degraded to a mere cipher or phantom.” He adds, in

conclusion: “I therefore now, on these and various other grounds,

formally protest, before her majesty and the country, against the

opinion or report (which, be it observed, is certainly not in law a

sentence or final judgment) delivered by the House of Lords on the 5th

of August 1853 as unjust in itself, proceeding on error and

misrepresentation throughout, and as having, in its principles, and in

its application of those principles, a direct tendency to revolutionize

the whole system of peerage law, and, indeed, to innovate on other

departments of law, and certainly of justice, hitherto sacred from such

encroachments.”

_____

MONTROSE, Earl,

marquis and duke of, titles in the peerage of Scotland, possessed by the

noble family of Graham, whose origin and descent have been already

given. They were first ennobled in the person of Patrick Graham of

Kincardine, who in 1451 was created Lord Graham. His grandson, William,

third Lord Graham, was on 3d March 1505, created earl of Montrose, the

title being derived from his hereditary lands of “Auld Montrose” and not

from the town of that name. He fell at the battle of Flodden, 9th

September 1513. He was thrice married. By his first wife, Annabella,

daughter of John, Lord Drummond, he had, William, second earl. By his

second wife, a daughter of Sir Archibald Edmonstone of Duntreath, he had

three daughters; and by his third wife, Christian Wawane of Segy, relict

of Patrick, sixth Lord Halyburton of Dirletoun, he had two sons;

Patrick, ancestor of the Grahams of Inchbraco, Gorthy, Bucklivie, and

other families of the name; and Andrew, consecrated bishop of Dunblane

in 1575.

William, second earl of Montrose, was one of the peers to whom the

regent duke of Albany committed the charge of the young king, James V.,

when he himself went to France in 1517. He was one of the commissioners

of regency appointed by that monarch on 29th August 1536, during his

majesty’s absence in France, and in 1543, he was chosen by the Estates

of the kingdom, along with Lord Erskine, to remain continually in the

castle of Stirling with Queen Mary, for the sure keeping of her person.

He died 24th May 1571. By his countess, Lady Janet Keith, eldest

daughter of William, third earl Marischal, he had four sons and five

daughters. Robert, Lord Graham, the eldest son, fell at the battle of

Pinkie, 10th September 1547. His posthumous son, John, by his wife,

Margaret, daughter of Malcolm, Lord Fleming, became third earl of

Montrose. The Hon. Mungo Graham of Orchill, the third son, was

great-grandfather of James Graham of Orchill, who, as nearest agnate

above 25 years of age, was served tutor at law of James, fourth marquis

of Montrose, 16th March 1688. The Hon. William Graham, the fourth son,

was ancestor of the Grahams of Killearn.

John, third earl of

Montrose, succeeded his grandfather in May 1571, and on 7th September

the same year, he was appointed a privy councilor at the election of the

regent Mar. He was one of the commissioners for the king, who concluded

the Pacification of Perth, February 3d, 1572. On the king’s assumption

of authority in 1578, he was appointed a privy councilor. He joined the

faction against the regent Morton, and was one of the principal among

those who, in 1581, brought him to the block; with the court favourite,

the earl of Arran, he guarded him from Dumbarton to Edinburgh, to stand

his trial, and as chancellor of the jury returned the verdict of “Guilty

art and part” against him, circumstances which necessarily led to a feud

between Montrose and the powerful family of Douglas. In 1583 the castle

of Glasgow, then held for the duke of Lennox, surrendered to him. He was

appointed an extraordinary lord of session, 12th May 1584, in the room

of the earl of Gowrie, who was beheaded on the 4th of that month, and on

the 13th he succeeded that nobleman as lord-treasurer. After the return

of the earl of Angus and the banished lords in November 1585, he was

deprived of both offices. On 6th November 1591, he was again admitted an

extraordinary lord of session, the king’s letter bearing that he had

“been dispossessed of the place of befoir without ony guid caus or

occasion.” He was appointed high-treasurer of Scotland, 13th May 1584,

and lord-chancellor, 15th January 1599, after the office had been vacant

for more than three years.

After James’ accession to

the throne of England, the earl of Montrose was nominated

lord-high-commissioner to the Estates which met at Edinburgh 10th April

1604. In a continuation of this parliament held at Perth 11th July,

1604, he was appointed one of the commissioners for the treaty of union

then projected between the two kingdoms of Scotland and England. Having

resigned the office of chancellor, it was conferred on Alexander Seton,

Lord Fyvie, one of the lords of session, and in recompense, a patent was

granted by the king to the earl, dated at Royston, in December 1604,

creating him viceroy of Scotland for life, the highest dignity a subject

can enjoy, and bestowing on him a pension of £2,000 Scots. In virtue of

this commission he presided at the meeting of the Estates at Perth, 9th

July 1606, wherein the Episcopal government in the church was restored.

His name appears as commissioner to the parliament which met at

Edinburgh 18th March 1607. He died 9th November 1608, in his 61st year.

Calderwood says: “Because he had been his majesty’s grand commissioner

in the parliaments preceding, and at conventions, his majesty thought

meet that he should he buried in pomp, before any other were named. So

he was buried with great solemnity. The king promised to bestow forty

thousand merks upon the solemnity of the burial, but the promise was not

performed, which drew on the greater burden upon his son.” (Hist. of the

Kirk of Scotland, vol. vii. P. 38.) By his countess, Jean, eldest

daughter of David, Lord Drummond, he had three sons and a daughter. The

sons were, 1. John, fourth earl; 2. Sir William Graham of Braco; and 3.

Sir Robert Graham of Scottistown.

John, fourth earl, was

appointed president of the council in July 1626, and died 24th November

same year. In Birrel’s Diary (p. 34), under date 19th January 1595, it

is mentioned that the young earl of Montrose fought, a combat with Sir

James Sandilands at the Salt Trone of Edinburgh, thinking to have

revenged the slaughter of his cousin, Mr. John Graham, who was slain by

the pistol-shot, and four of his men killed with swords. The fourth earl

married Lady Margaret Ruthven, eldest daughter of the first earl of

Gowrie, who was executed for treason in 1584. He had one son, James,

fifth earl and first marquis of Montrose, and five daughters. A memoir

of the first marquis of Montrose is given earlier (See James GRAHAM.) By

his countess, Lady Magdalen Carnegie, sixth daughter of the first earl

of Southesk, the first marquis had two sons. The elder, Lord Graham,

earl of Kincardine, a youth of great promise, accompanied his father in

his campaign of 1645, and died at the Bog of Gight in Strathbogie, in

March of that year, when only sixteen years of age, and was buried at

Bellie church.

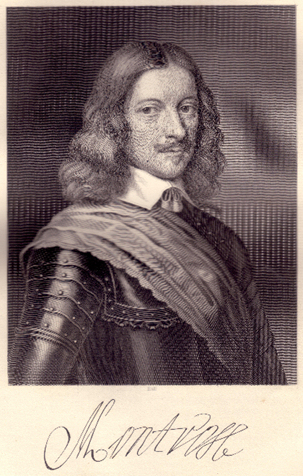

[portrait of the Great Marquis of Montrose]

James, second marquis,

called the good marquis, as his father is called the great marquis of

Montrose, was born about 1631. He was restored to the family estates,

sworn a privy councilor, and had a patent of the title of marquis of

Montrose, 12th October 1660. On the trial of the marquis of Argyle, the

great enemy of his father, in 1661, the marquis of Montrose refused to

vote, as he felt too much resentment to judge in the matter, (Burnet’s

History, vol. i. p. 213). He was appointed one of the extraordinary

lords of session, 25th June 1668, but died in February following. He

married Lady Isabella Douglas, countess dowager of Roxburgh, fifth

daughter of the second earl of Morton, and with one daughter had two

sons, James, third marquis, and Lord Charles Graham, who died young.

James, third marquis,

being a minor at his father’s death, the king, Charles II., took him

under his immediate protection, appointed him captain of the guards, and

afterwards president of the council. At the trial of the earl of Argyle,

12th December 1681, the marquis of Montrose, his cousin-german, was

chancellor of the jury who found him guilty. He died 25th April 1684. By

his wife, Lady Christian Leslie, second daughter of the duke of Rothes,

chancellor of Scotland, he had a son, James, fourth marquis and first

duke of Montrose. As the latter was a mere child when he succeeded to

the titles and estates of his family, his father had nominated as his

tutors, his mother, the earls of Haddington and Perth, Hay of

Drummelzier, and Sir William Bruce of Kinross. The marchioness, his

mother, took for her second husband, Sir John Bruce, younger of Kinross,

and on her marriage, the tutory was found null by decision of the court

of session, 1st February 1688. This was thought to be a device of the

king, James VII., to have the young marquis educated as a Roman

Catholic. But if so, he had no opportunity of carrying his design into

effect, as he was then fast verging to his fall. The case was rendered

remarkable by two of the judges who had voted in favour of the tutors

selected by his father, Lords Harcarse and Edmonstone, being, in

consequence, removed from their seats on the bench, by a letter from the

king himself. His nearest agnate, Graham of Braco, being under 25 years

of age, could not be tutor at law, and James Graham of Orchill, the

nearest agnate above 25, was accordingly served his tutor.

In 1702 the marquis made

a great addition to his estates by purchasing the property of the duke

of Lennox, as well as many of its jurisdictions; among these were the

hereditary sheriffdom of Dumbarton, the custodianship of Dumbarton

castle, and the jurisdiction of the regality of Lennox. He was appointed

high-admiral of Scotland, 23d February 1705, and president of the

council, 28th February 1706. He steadily supported the union and the

protestant succession, and was advanced to the dignity of duke of

Montrose by patent, dated 24th April 1707. He was one of the sixteen

Scots representative peers chosen by the last parliament of Scotland,

13th February 1707, and re-chosen at the general election of 1708. He

was subsequently three times re-elected. Appointed keeper of the privy

seal of Scotland, 28th February 1709, he was removed in 1713, for not

complying with the Tory administration. At the death of Queen Anne the

following year, the duke of Montrose was appointed by George I. one of

the lords of the regency. He was one of the noblemen who attended the

proclamation of his majesty at Edinburgh, 5th August 1714, and on 24th

September, six days after the king had landed in England, his majesty

appointed his grace one of the principal secretaries of state in the

room of the earl of Mar, whose dismissal led to the rebellion of 1715.

His grace was sworn a privy councilor at St. James’, 4th October 1717.

He had been constituted keeper of the great seal in Scotland in 1716,

but was removed from that office in April 1733, in consequence of his

opposition to Sir Robert Walpole.

At the meeting of

parliament in 1735, a petition was presented, signed by six Scots

noblemen, the duke of Montrose being one, complaining of the undue

interference of government in the recent election of the sixteen Scots

representative peers. It stated that the peers had been solicited to

vote for a prepared list called the king’s list, that sums of money,

pensions, offices, and discharges of crown debts were actually granted

to peers who voted for it, and to their relations, and that on the day

of election a body of troops was drawn up in the Abbey court of

Edinburgh, evidently with the view of overawing the peers at the

election. So strong, however, was the ministry at the time that the

petition was rejected.

In the celebrated Rob Roy

Macgregor Campbell, the duke, when marquis of Montrose, found a

persevering and irreconcilable enemy, who turned him into ridicule and

set all his power and influence at defiance. Rob Roy had been so

successful in his profession of a drover or cattle-dealer, that before

the year 1707 he had purchased the lands of Craigrostane, on the banks

of Lochlomond, from the family of Montrose, and relieved the estate of

Glengyle, the property of his nephew, from considerable debts. Previous

to the union of the two kingdoms no cattle were permitted to be imported

into England, but free intercourse being allowed by the treaty of union,

various speculators engaged in this traffic, and among others, the

marquis of Montrose, afterwards created duke, and Rob Roy entered into a

joint adventure. The capital to be advanced was fixed at 10,000 merks

each, and Rob Roy was to purchase the cattle and drive them to England

for sale. Macgregor made his purchases accordingly, but finding the

market overstocked on his arrival in England, he was obliged to sell the

cattle below prime cost. The duke refused to bear any share of the loss,

and insisted on repayment of the whole money advanced by him with

interest. Macgregor refused to pay either principal or interest, and

having spent the duke’s money in organizing a body of the Macgregors in

1715, under the nominal command of his nephew, his grace took legal

means to recover it, and in security seized the lands of Craigrostane.

This proceeding so exasperated Macgregor that he resolved in future to

supply himself with cattle from his grace’s estates, and for nearly

thirty years, down to the day of his death, he carried off the duke’s

cattle with impunity, and disposed of them publicly in different parts

of the country. Although these cattle generally belonged to the duke’s

tenants, his grace was the ultimate sufferer, as they were unable to pay

their rents, to liquidate which their cattle mainly contributed.

Macgregor also levied contributions in mean and money, but he never took

it away till delivered to the duke’s storekeeper in payment of rent, and

he then gave the storekeeper a receipt for the quantity taken. At

settling the money rents Macgregor often attended, and several instances

are recorded of his having compelled the duke’s factor to pay him a

share of the rents, which he took good care to see were discharged to

the tenants beforehand.

His grace, who was

chancellor of the university of Glasgow, died at London 7th January

1742. From a portrait of him by Sir John Medina, engraved by Cooper, the

subjoined woodcut is taken:

[woodcut of duke of Montrose]

By his duchess, Lady

Christian Carnegie, second daughter of the third earl of Northesk, he

had, with one daughter, four sons, namely, 1st, James, marquis of

Graham, who died in infancy; 2d, David, marquis of Graham, created a

peer of Great Britain, by the titles of Earl and Baron Graham of Belford

in Northumberland, 23d May 1722, with remainder to his brothers. He took

the oaths and his seat in the House of Lords, 19th January 1727, and

died, unmarried, 2d October 1731, in his father’s lifetime; 3d, William,

second duke of Montrose; and 4th, Lord George Graham, a captain R.N.,

who in 1740 was appointed governor of Newfoundland. At the general

election of 1741 he was chosen M.P. for Stirlingshire. He saw a good

deal of active service afloat, and Aaron Hill wrote a poem to him on his

action near Ostend, 24th June 1745. He died, unmarried, at Bath, 2d

January 1747. In Buchanan House, Stirlingshire, the seat of the family,

there is a painting, about quarter size, by Hogarth. It represents Lord

George Graham at table in the cabin of his ship with attendants. Some

parts of the group bear marks of the characteristic humour of the

immortal artist.

William, second duke of

Montrose, was in August 1723, on the recommendation of some of the

professors of the university of Edinburgh, placed, with his brother,

under the tuition of David Mallet, the poet, at that time a young man

still bearing his father’s name of Malloch. On his arrival, the same

month, at Shawford near Winchester, where the family resided, Mallet

wrote to a friend, “Both my lord and my lady received me kindly, and as

for my Lord William and Lord George, I never saw more sprightly or more

hopeful boys.” With their tutor they made the tour of Europe, and Mallet

translated Bossuet’s ‘Discours sur l’Historie Universelle’ for the use

of his young charge.

In 1731, his grace, then

Lord William Graham, succeeded his elder brother in the British peerage

of Earl and Baron Graham of Belford. He also then became, by courtesy,

marquis of Graham, as heir to the dukedom. On the 12th July 1739, the

following adventure occurred to him. Riding at some distance before his

servant near Farnham in Surrey, he was attacked in a by-lane by two

highwaymen, one of whom, laying hold of the bridle of his horse, and

bidding him deliver, his lordship drew a pistol, and shot him through

the head. The other robber, snapping his pistol, made off, and was

pursued by his lordship, till quitting his horse, he escaped into a

wood.

On his father’s death is

1742, he became second duke of Montrose. Under the abolition of the

heritable jurisdictions act of 1747, his grace was allowed as

compensation for his hereditary office, in £5,578 18s 4d. in full of his

claim of £15,000; being, for the sheriffship of Dumbarton £3,000, the

regality of Montrose £1,000, of Menteith £200, of Lennox £378 18s 4d,

and of Darnley £800. He died 23d September 1790. By his duchess, Lady

Lucy Manners, youngest daughter of John, second duke of Rutland, he had

two sons, and a daughter, Lady Lucy Graham, married to the first Lord

Douglas of Douglas. The elder son died the day he was born.

James, third duke of

Montrose, the youngest of the family, born 8th September 1755, was

educated at Trinity college, Cambridge, where he took the degree of M.A.

At the general election of 1780, he was chosen one of the members for

Richmond in Yorkshire. He zealously opposed Mr. Fox’s India bill, and on

the formation of the Pitt administration, 17th December 1783, his

lordship was appointed one of the lords of the treasury.

In 1784 he was chosen one

of the representatives of Great Bedwin, in Wiltshire. On 10th June that

year he became president of the Board of Trade, on 13th July joint

postmaster-general, and on 6th August, jointly with Lord Mulgrave,

paymaster of the forces. He procured the repeal of the prohibitory act

of 1747, whereby the Highlanders obtained the restoration of their

ancient dress, which had been proscribed after the last rebellion. In

1789, when, on the illness of George III., the project of a regency was

supported with great zeal by the opposition, Burke was, on one occasion,

so carried away by the violence of his feelings that, in reference to

his majesty, he declared “the Almighty had hurled him from his throne.”

The marquis, who was seated beside Pitt on the treasury bench, instantly

started to his feet, and with great warmth exclaimed, “No individual

within these walls shall dare to assert that the king was hurled from

his throne.” A scene of great confusion ensued. On the recovery of his

majesty, the marquis was the mover of the address to the queen.

On the death of his

father in September 1790, he succeeded to the dukedom. In November of

the same year he was appointed master of the horse, and on 12th May

1791, he was constituted one of the commissioners for the affairs of

India, and sworn a privy councilor. He was made a knight of the Thistle,

14th June 1793, and in 1795 was appointed lord-justice-general of

Scotland, when he resigned the mastership of the horse. On the change of

administration in February 1806, his grace was removed from the

presidency of the Board of Trade, and the joint postmaster-generalship,

but on his friends coming into April 1807. He retained that office till

1821, when he succeeded the marquis of Hertford as lord-chamberlain.

This last office he resigned in 1827. In 1812 he had been elected one of

the knights of the Garter, under the regency of the prince of Wales. His

grace, like his father, was chancellor of the university of Glasgow. He

was also a general of the Royal Archers of Scotland, and lord-lieutenant

of the counties of Stirling and Dumbarton; D.C.L. He died Dec. 30, 1836.

In ‘Wraxall’s Memoirs of

his own Times,’ the following sketch of his grace is given; “Few

individuals, however distinguished by birth, talents, parliamentary

interest, or public services, have attained to more splendid

employments, or have arrived at greater honours than Lord Graham, under

the reign of George III. Besides enjoying the lucrative sinecure of

justice general of Scotland for life, we have seen him occupy a place in

the cabinet, while he was joint postmaster general, during Pitt’s second

ill-fated administration. In his person he was elegant and pleasing, as

far as those qualities depend on symmetry of external figure; nor was he

deficient in all the accomplishments befitting his illustrious descent.

He possessed a ready elocution, sustained by all the confidence in

himself necessary for addressing the house. Nor did he want ideas, while

he confined himself to common sense, to argument, and to matters of

fact. If, however, he possessed no distinguished talents, he displayed

various qualities calculated to compensate for the want of great

ability; particularly the prudence, sagacity, and attention to his own

interests, so characteristic of the Caledonian people. His celebrated

ancestor, the marquis of Montrose, scarcely exhibited more devotion to

the cause of Charles I. in the field, than his descendant displayed for

George III. in the house of commons. Nor did he want great energy, as

well as activity of mind and body. During the progress of the French

Revolution, when the fabric of our constitution was threatened by

internal and external attacks, Lord Graham, then become duke of

Montrose, enrolled himself as a private soldier in the city light horse.

During several successive years, he did duty in that capacity, night and

day, sacrificing to it his ease and his time; thus holding out an

example worthy of imitation to the British nobility.”

He was twice married,

first, to the eldest daughter of the earl of Ashburnham, by whom he had

one son, William, earl of Kincardine, who died in his infancy; and,

2dly, to Lady Caroline Maria Montague, eldest daughter of George, 4th

duke of Manchester; issue, 2 sons and 4 daughters.

James, 4th duke, the

elder son, born in 1799, elected chancellor of the university of Glasgow

in 1837, and in 1843 appointed lord-lieutenant of Stirlingshire,

married, in 1836, previous to succeeding to the dukedom, 3d daughter of

Lord Decies; issue, 3 sons and 3 daughters. Sons: 1. James, born in

1845, died in 1846. 2. James, marquis of Graham, born June 22, 1847. 3.

Douglas-Beresford-Malise-Ronald, born Nov. 7, 1852. Major-general of the

Royal Archers, colonel of the Stirling, Dumbarton, Clackmannan, and

Kinross militia; a knight of the Thistle 1845; sworn a privy councilor

1850.

CREATIONS, --

Baron Graham, 1451, earl of Montrose, 1503, marquis of Montrose, earl of

Kincardine, Baron Graham and Mugdock, 1644, duke of Montrose, marquis of

Graham and Buchanan, viscount of Dunduff, Lord Aberruthven and Fintry,

1707, to the heirs male of the body of the first duke, whom failing, to

the heirs of the marquis of Montrose by former patents granted to his

ancestors; and Earl and Baron Graham of Belford in the peerage of Great

Britain, 1722, by which last creation the duke of Montrose holds his

seat in the House of Lords. The estate of Buchanan in Stirlingshire was

purchased by the third marquis, who is known to antiquarians as having

presented to the university of Glasgow one of the most beautiful of its

Roman remains. The family have long ceased to possess any connexion with

either the town of Montrose, whence they derive their principal title,

or its vicinity.

The Marquis of Montrose

By John Buchan (1913) (pdf)

Montrose

By John Buchan (1929) (pdf)

In September 1913 I published a short sketch of Montrose, which dealt

chiefly with his campaigns. The book went out of print very soon, and it

was not reissued, because I cherished the hope of making it the basis of

a larger work, in which the background of seventeenth-century politics

and religion should be more fully portrayed. I also felt that many of

the judgments in the sketch were exaggerated and hasty. During the last

fifteen years I have been collecting material for the understanding of a

career which must rank among the marvels of our history, and of a mind

and character which seem to me in a high degree worthy of the attention

of the modern reader. The manuscript sources have already been

diligently explored by others, and I have been unable to glean from them

much that is new; but I have attempted to supplement them by a study of

the voluminous pamphlet literature of the time. My aim has been to

present a great figure in its appropriate setting. In a domain, where

the dust of controversy has not yet been laid, I cannot hope to find for

my views universal acceptance, but they have not been reached without an

earnest attempt to discover the truth.

J. B.

ELSFIELD MANOR, OXON,

June, 1928. |