|

DOUGLAS, SIR JAMES, one of

the most remarkable men of the heroic age to which he belonged, and the

founder of the great fame and grandeur of one of the most illustrious

houses in Scotland, was the eldest son of William Douglas, a baron, or

magnate of Scotland, who died in England about the year 1302.

The ancestry of this family

have been but imperfectly and obscurely traced by most genealogists; but

it now seems to be established beyond doubt, that the original founder

came into this country from Flanders, about the year 1147; and, in reward

of certain services, not explained, which he performed to the abbot of

Kelso, received from that prelate a grant of lands on the water of

Douglas, in Lanarkshire. In this assignation, a record of which is yet

extant, he is styled Theobaldus Flammaticus, or Theobald the Fleming.

William, the son and heir of Theobald, assumed the surname of Douglas,

from his estate. Archibald de Douglas, his eldest son, succeeded in the

family estate on Douglas water. Bricius, a younger son of William, became

bishop of Moray, in 1203; and his four brothers, Alexander, Henry, Hugh,

and Freskin, settled in Moray under his patronage, and from these, the

Douglases of Moray claim their descent. Archibald died between the years

1238 and 1240, leaving behind him two sons. William, the elder, inherited

the estate of his father; Andrew, the younger, became the ancestor of the

Douglases of Dalkeith, afterwards created earls of Morton. William

acquired additional lands to the family inheritance; and, by this means,

becoming a tenant in chief of the crown, was considered as ranking among

the barons, or, as they were then called, magnates of Scotland. He died

about the year 1276, leaving two sons, Hugh and William. Hugh fought at

the battle of the Largs, in 1263, and died about 1288, without issue.

William, his only brother, and father to Sir James, the subject of the

present article, succeeded to the family honours, which he did not long

enjoy; for, having espoused the popular side in the factions

which soon after divided the kingdom, he was, upon the successful

usurpation of Edward I., deprived of his estates, and died a prisoner in

England, about the year 1302. Of this ancestor, the first whose history

can be of any interest to the general reader, we have made mention in the

life of Wallace, and, therefore, have no occasion to recur to him in this

place.

The young Douglas had not

attained to manhood, when the captivity of his father left him unprotected

and destitute; and in this condition, either prompted by his own

inclination, or influenced by the suggestions of friends anxious for his

safety, he retired into France, and lived in Paris for three years. In

this capital, remarkable, even in that age, for the gayety and show of its

inhabitants, the young Scotsman for a time forgot his misfortunes, and

gave way with youthful ardour to the current follies by which he was

surrounded. The intelligence of his father’s death, however, was

sufficient to break him off entirely from the loose courses upon which he

was entering, and incite him to a mode of life more honourable, and more

befitting the noble feelings by which, throughout life, he was so strongly

actuated. Having returned without delay into Scotland, he seems first to

have presented himself to Lamberton, bishop of St Andrews, and was

fortunate enough to be received with great kindness by that good prelate,

who promoted him to the honourable post of page in his household. Barbour,

the poet, dwells fondly upon this period in the life of Douglas, whom he

describes as cheerful, courteous, dutiful, and of a generous disposition,

insomuch, that he was esteemed and beloved by all; yet was he not so fair,

adds the same discreet writer, that we should much admire his beauty. He

was of a somewhat grey or swarthy complexion, and had black hair,

circumstances from which, especially among the English, he came to be

known by the name of the Black Douglas. His bones were large, but well

set; his shoulders broad, and his whole person to be remarked as rather

spare or lean, though muscular. He was mild and pleasant in company, or

among his friends, and lisped somewhat in his speech, a circumstance which

is said not at all to have misbecome him, besides that it brought him

nearer to the beau ideal of Hector, as Barbour fails not to remark, in a

not inappropriate comparison, which he attempts making of the two

characters.

Douglas was living in this

manner, when Edward, having for the last time, overrun Scotland, called

together an assembly of the barons at Stirling. The bishop of St Andrews

attended the summons of the English king on this occasion; and taking

along with him the young squire whom he had so generously protected,

resolved, if possible, to interest the monarch in his fortunes. Taking

hold of a suitable opportunity, the prelate presented Douglas to the king,

as a youth who claimed to be admitted to his service, and at the same

time, made earnest entreaty that his majesty would look favourably upon

him, and restore him to the inheritance, which, from no fault of his, he

had lost. "What lands does he claim?" inquired Edward. The good

bishop had purposely kept the answer to this question to the end, well

knowing the hasty and vindictive temper of the English king, and the

particular dislike which he bore to the memory of the former Douglas; but

he soon saw that the haughty conqueror was neither to be prepossessed nor

conciliated. Edward no sooner understood the birth of the suitor, than,

turning angrily to the bishop, he reproached him, in harsh terms, for his

presumption. "The father," said he, "was always my enemy;

and I have already bestowed his lands upon more loyal followers than his

sons can ever prove." The unfavourable issue of this suit must have

left a deep and resentful impression on the mind of the young Douglas; and

it was not long before an occasion offered whereby he might fully discover

the incurable inveteracy of his hostility to the English king.

While he yet resided at the

bishop’s palace, intelligence of the murder of Comyn, and the revolt of

Bruce, spread over the kingdom. Lamberton, who, it is well known, secretly

favoured the insurrection, not only made no difficulty of allowing the

young Douglas to join the party, but even assisted him with money to

facilitate his purpose. The bishop, it is also said, directed him to seize

upon his own horse for his use, as if by violence, from the groom; and,

accordingly, that servant in an unwitting attention to his duty, having

been knocked down, Douglas, unattended, rode off to join the standard of

his future king and master. He fell in with the party of Bruce at a place

called Errickstane, on their progress from Lochmaben towards Glasgow;

where, making himself known to Robert, he made offer to him of his

services; hoping that under the auspices of his rightful sovereign, he

might recover possession of his own inheritance. Bruce, well pleased with

the spirit and bearing of his new adherent, and, besides, interested in

his welfare, as the son of the gallant Sir William Douglas, received him

with much favour, giving him, at the same time, a command in his small

army. This was the commencement of the friendship between Bruce and

Douglas, than which, none more sincere and perfect ever existed between

sovereign and subject.

It would, of course, be

here unnecessary to follow Sir James Douglas, as we shall afterwards name

him, through the same tract described in the life of his heroic master; as

in that, all which it imports the reader to know has been already detailed

with sufficient minuteness. Of the battle of Methven, therefore, in which

the young knight first signalized his valour; that of Dalry, in which

Robert was defeated by the lord of Lorn, and Sir James wounded; the

retreat into Rachrin; the descent upon Arran, and afterwards on the coast

of Carrick; in all of which enterprises, the zeal, courage, and usefulness

of Douglas were manifested, we shall in this place take no other notice,

than by referring to the life which we have mentioned. Leaving these more

general and important movements, we shall follow the course of our

narrative in others more exclusively referable to the life and fortunes of

Douglas.

While Robert the Bruce was

engaged in rousing the men of Carrick to take up arms in his cause,

Douglas was permitted to repair to his patrimonial domains in Douglasdale,

for the purpose of drawing over the ancient and attached vassals of his

family to the same interest, and, in the first place, of avenging, should

an occasion offer, some of the particular wrongs himself and family had

sustained from the English. Disguised, therefore, and accompanied by only

two yeomen, Sir James, towards the close of an evening in the month of

March, 1307, reached the alienated inheritance of his house, then owned by

the lord Clifford, who had posted within the castle of Douglas a strong

garrison of English soldiers. Having revealed himself to one Thomas

Dickson, formerly his father’s vassal, and a person possessed of some

wealth, and considerable influence among the tenantry, Sir James, and his

two followers were joyfully welcomed, and carefully concealed within his

house. By the diligence and sagacity of this faithful dependent, Douglas

was soon made acquainted with the numbers of those, in the neighbourhood,

who would be willing to join him in his enterprise, and the more important

of these being brought secretly, and by one or two at a time, before him,

he received their pledges of fidelity and solemn engagements to assist him

to the utmost of their power towards the recovery of his inheritance.

Having, in this manner, secured the assistance of a small, but resolute

band, Sir James determined to put in execution a project which he had

planned for the surprisal of the castle. The garrison, entirely ignorant

and unsuspicious of the machinations of their enemies, and otherwise far

from vigilant, offered many opportunities which might be taken advantage

of to their destruction. The day of Palm Sunday, however, was fixed upon

by Douglas, as being then near at hand, and as furnishing, besides, a

plausible pretext for the gathering together of his adherents. The

garrison, it was expected, would, on that festival, attend divine service

in the neighbouring church of St Bride. The followers of Douglas having

arms concealed upon their persons, were, some of them, to enter the

building along with the soldiers, while the others remained without to

prevent their escape. Douglas, himself, disguised in an old tattered

mantle, having a flail in his hand, was to give the signal of onset, by

shouting the war cry of his family. When the concerted day arrived, the

whole garrison, consisting of thirty men, went in solemn procession to

attend the service of the church, leaving only the porter and the cook

within the castle. The eager followers of the knight did not wait for the

signal of attack; for, no sooner had the unfortunate Englishmen entered

the chapel, than, one or two raising the cry of "a Douglas, a

Douglas," which was instantly echoed and returned from all

quarters, they fell with the utmost fury upon the entrapped garrison.

These defended themselves bravely, till two thirds of their number lay

either dead or mortally wounded. Being refused quarter, those who yet

continued to fight were speedily overpowered and made prisoners, so that

none escaped. Meanwhile, five or six men were detached to secure

possession of the castle gate, which they easily effected: and being soon

after followed by Douglas and his partisans, the victors had now only to

deliberate as to the use to which their conquest should be applied.

Considering the great power and numbers of the English in that district,

and the impossibility of retaining the castle should it be besieged;

besides, that the acquisition could then prove of no service to the

general cause, it was determined, that that which could be of little or no

service to themselves, should be rendered equally useless and unprofitable

to the enemy. This measure, so defensible in itself and politic, was

stained by an act of singular and atrocious barbarity; which, however

consistent with the rude and revengeful spirit of the age in which it was

enacted, remains the sole stigma which even his worst enemies could ever

affix to the memory of Sir James Douglas. Having plundered and stripped

the castle of every article of value which could be conveniently carried

off and secured; the great mass of the provisions, with which it then

happened to be amply provided, were heaped together within an apartment of

the building. Over this pile were stored the puncheons of wine, ale, and

other liquors which the cellar afforded; and lastly the prisoners who had

been taken in the church, having been despatched, their dead bodies were

thrown over all; thus, in a spirit of savage jocularity, converting the

whole into a loathsome mass of provision, then, and long after, popularly

described by the name of the Douglas’ Larder. These savage

preparations gone through, the castle was set on fire, and burned to the

ground.

No sooner was Clifford

advertised of the miserable fate which had befallen his garrison, than,

collecting a sufficient force, he repaired to Douglas in person; and

having caused the castle to be re-edified more strongly than it had been

formerly, he left a new garrison in it under the command of one Thirlwall,

and returned himself into England. Douglas, while these operations

proceeded, having dispersed his followers, bestowing in secure places,

where they might be properly attended to, such among them as had been

wounded, himself lurked in the neighbourhood, intending, on the first safe

opportunity, to rejoin the king’s standard, in company with his trusty

adherents. Other considerations, however, seem to have arisen, and to have

had their share in influencing his conduct in this particular; for the

lord Clifford had no sooner departed, than he resolved, a second time, to

attempt the surprisal of his castle, under its new governor. The garrison,

having a fresh remembrance of the fatal disaster which had befallen their

predecessors, were not to be taken at the same advantage; and some

expedient had therefore to be adopted which might abate the extreme

caution and vigilance, which they observed, and on which their safety

depended. This Douglas effected, by directing some of his men, at

different times, to drive off portions of the cattle belonging to the

castle, but who, as soon as the garrison issued out to the rescue, were

instructed to leave their booty and betake themselves to flight. The

governor and his men having been sufficiently irritated by the attempts of

these pretended plunderers, who thus kept them continually and vexatiously

on the alert, Sir James, aware of their disposition, resolved, without

further delay, upon the execution of his project. Having formed an ambush

of his followers at a place called Sandilands, at no great distance from

the castle, he, at an early hour in the morning, detached a few of his

men, who very daringly drove off some cattle from the immediate vicinity

of the walls, towards the place where the ambuscaders lay concealed.

Thirlwall was no sooner apprized of the fact, than, indignant at the

boldness of the affront put upon him, which yet he considered to be of the

same character with those formerly practised, hastily ordered a large

portion of the garrison to arm themselves and follow after the spoilers,

himself accompanying them with so great precipitation, that he did not

take time even to put on his helmet. The pursuers, no ways suspecting the

snare laid for them, followed, in great haste and disorder, after the

supposed robbers, but had scarcely passed the place of the ambush, than

Douglas and his followers starting suddenly from their covert, the party

at once found themselves circumvented and their retreat cut off. In their

confusion and surprise, they were but ill prepared for the fierce assault

which was instantly made upon them. The greater part fled precipitantly,

and a few succeeded in regaining their strong-hold; but Thirlwall and many

of his bravest soldiers were slain. The fugitives were pursued with great

slaughter to the very gates of the castle; but, though few in numbers,

having secured the entrance, and manned the walls, Sir James found it

would be impossible to gain possession of the place at this time.

Collecting together, therefore, all those willing to join the royal cause,

he forthwith repaired to the army of Bruce, then encamped at Cumnock, in

Ayrshire. The skill and boldness which Douglas displayed in these two

exploits, and the success which attended them, added to the reputation for

military enterprise and bravery, which he had previously acquired, seem to

have infected the English with an almost superstitious dread of his power

and resources; so that, if we may believe the writers of the age, few

could be found adventurous enough to undertake the keeping of "the

perilous castle of Douglas," for by that name it now came to be

popularly distinguished.

When king Robert, shortly

after his victory over the English at Loudonhill, marched his forces into

the north of Scotland, Sir James Douglas remained behind, for the purpose

of reducing the forests of Selkirk and Jedburgh to obedience. His first

adventure, however, was the taking, a second time, his own castle of

Douglas, then commanded by Sir John de Wilton, an English knight, who held

this charge, as his two predecessors had done, under the lord Clifford,

Sir James, taking along with him a body of armed men, gained the

neighbourhood undiscovered, where himself and the greater number

immediately planted themselves in ambuscade, as near as possible to the

gate of the castle. Fourteen of his best men he directed to disguise

themselves as peasants wearing smock-frocks, under which their arms might

be conveniently concealed, and having sacks filled with grass laid across

their horses, who, in this guise, were to pass within view of the castle,

as if they had been countrymen carrying corn for sale to Lanark fair.

The stratagem had the desired effect; for the garrison being then

scarce of provisions, had no mind to let pass so favourable an

opportunity, as it appeared to them, of supplying themselves; wherefore,

the greater part, with the governor, who was a man of a bold and reckless

disposition, at their head, issued out in great haste to overtake and

plunder the supposed peasants. These, finding themselves pursued, hurried

onward with what speed they could muster, till, ascertaining that the

unwary Englishmen had passed the ambush, they suddenly threw down their

sacks, stripped off the frocks which concealed their armour, mounted their

horses, and raising a loud shout, seemed determined in turn to become the

assailants. Douglas and his concealed followers, no sooner heard the shout

of their companions, which was the concerted signal of onset, than,

starting into view in the rear of the English party, these found

themselves at once, unexpectedly and furiously attacked from two opposite

quarters. In this desperate encounter, their retreat to the castle being

effectually cut off, Wilton and his whole party are reported to have been

slain. When this successful exploit was ended, Sir James found means to

gain possession of the castle, probably by the promise of a safe conduct

to those by whom it was still maintained; as he allowed the constable and

remaining garrison to depart unmolested into England, furnishing them, at

the same time, with money to defray the charges of their journey. Barbour

relates, that upon the person of the slain knight there was found a letter

from his mistress, informing him, that he might well consider himself

worthy of her love, should he bravely defend for a year the adventurous

castle of Douglas. Sir James razed the fortress of his ancestors to the

ground, that it might, on no future occasion, afford protection to the

enemies of his country, and the usurpers of his own patrimony.

Leaving the scene where he

had thus, for the third time, in so remarkable a manner triumphed over his

adversaries, Douglas proceeded to the forests of Selkirk and Jedburgh,

both of which he in a short time reduced to the king’s authority. While

employed upon this service, he chanced one day, towards night-fall, to

come in sight of a solitary house on the water of Line, which he had no

sooner perceived, than he directed his course towards it, with the

intention of there resting himself and his followers till morning.

Approaching the place with some caution, Douglas could distinguish from

the voices which he heard within, that it was pre-occupied; and from the

oaths which mingled in the conversation, he had no doubt as to the

character of the guests which it contained, military men being then,

almost exclusively, addicted to the use of such terms in their speech.

Having beset the house with his followers, and forced an entrance,

the conjecture of the knight proved well founded; for, after a brief but

sharp contest with the inmates, he was fortunate enough to secure the

persons of Alexander Stuart, Lord Bonkle, and Thomas Randolph, the king’s

nephew; who were, at that time, not only attached to the English interest,

but engaged in raising forces to check the progress of Douglas in the

south of Scotland. The important consequences of this action, by which

Robert gained as wise and faithful a counsellor as he ever possessed, and

Douglas a rival, though a generous one even in his own field of glory,

deserves that it should be particularly noticed in this place. Immediately

upon this adventure, Douglas, carrying along with him his two prisoners;

rejoined the king’s forces in the north; where, under his gallant

sovereign, he assisted in the victory gained over the lord of Lorn, by

which the Highlands were at length constrained to a submission to the

royal authority.

Without following the

current of those events, in which Douglas either participated, or bore a

principal part, but which have more properly fallen to be described in

another place, we come to the relation of one more exclusively belonging

to the narration of this life. The castle of Roxburgh, a fortress of great

importance on the borders of Scotland, had long been in the hands of the

English king, by whom it was strongly garrisoned, and committed to the

charge of Gillemin de Fiennes, a knight of Burgundy. Douglas, and his

followers, to the number of about sixty men, then lurked in the adjoining

forest of Jedburgh, where they did not remain long inactive, before the

enterprising genius of their leader had suggested a plan for the surprisal

of the fortress. A person of the name of Simon of Leadhouse was employed

to construct rope-ladders for scaling the walls, and the night of

Shrove-Tuesday, then near at hand, was fixed upon as the most proper for

putting the project in execution; "for then," says Fordun,

"all the men, from dread of the Lent season, which was to begin next

day, indulged in wine and licentiousness." When the appointed night

arrived, Douglas and his brave followers approached the castle, wearing

black frocks or shirts, over their armour, that, in the darkness, they

might be the more effectually concealed from the observation of the

sentinels. On getting near to the castle walls, they crept softly onwards

on their hands and knees; and, indeed, soon became aware of the necessity

they were under of observing every precaution; for a sentinel on the walls

having observed, notwithstanding the darkness, their indistinct crawling

forms, which he took to be those of cattle, remarked to his companion,

that farmer such a one (naming a husbandman who lived in the neighbourhood)

surely made good cheer that night, seeing that he took so little care of

his cattle. "He may make merry to-night, comrade," the other

replied, "but, if the Black Douglas come at them, he will fare the

worse another time;" and, so conversing, these two passed to another

part of the wall. Sir James and his men had approached so close to the

castle, as distinctly to overhear this discourse, and also to mark with

certainty the departure of the men who uttered it. The wall was no sooner

free of their presence, than Simon of the Leadhouse, fixing one of the

ladders to its summit, was the first to mount. This bold adventure was

perceived by one of the garrison so soon as he reached the top of the

wall; but, giving the startled soldier no time to raise an alarm, Simon

sprang suddenly upon him, and despatched him with his dagger. Before the

others could come to his support, Simon had to sustain the attack of

another antagonist, whom, also, he laid dead at his feet; and Sir James

and his men, in a very brief space, having surmounted the wall, the loud

shout of "a Douglas! a Douglas!" and the rush of the

enemy into the hall, where the garrison yet maintained the revels of the

evening, gave the first intimation to governor and men that the fortress

had been assaulted and taken. Unarmed, bewildered, and most of them

intoxicated, the soldiery were unable to make any effectual resistance;

and in this defenceless and hopeless state, many of them in the fury of

the onset were slaughtered. The governor and a few others escaped into the

keep or great tower, which they defended till the following day; but

having sustained a severe arrow wound in the face, Gillemin de Fiennes

thought proper to surrender, on condition that he and his remaining

followers should be allowed safely to depart into England. These terms

having been accorded, and faithfully fulfilled, Fiennes died shortly

afterwards of the wound which he had received. This event, which fell out

in the month of March., 1313, added not a little to the terror with which

the Douglas name was regarded in the north of England; while in an

equal degree, it infused spirit and confidence into the hearts of their

enemies. Barbour attributes the successful capture of Edinburgh castle by

Randolph, an exploit of greater peril and on that account only, of

superior gallantry to the preceding, to the noble emulation with which the

one general regarded the deeds of the other.

The next occasion, wherein

Douglas signalized himself by his conduct and bravery, was on the field of

Bannockburn; in which memorable battle, he had the signal honour of

commanding the centre division of the Scottish van. When the fortune of

that great day was decided, by the disastrous and complete overthrow of

the English army, Sir James, at the head of sixty horsemen, pursued

closely on the track of the flying monarch, for upwards of forty miles

from the field, and only desisted from the chase from the inability of his

horses to proceed further. In the same year, king Robert, desirous of

taking advantage of the wide spread dismay into which the English nation

had been thrown, despatched his brother Edward and Sir James Douglas, by

the eastern marches, into England, where they ravaged and assessed at will

the whole northern counties of that kingdom.

When Bruce passed over with

an army into Ireland, in the month of May 1316, in order to the

reinforcement of his brother Edward’s arms in that country, he committed

to Sir James Douglas, the charge of the middle borders, during his

absence. The earl of Arundel appears, at the same time, to have commanded

on the eastern and middle marches of England, lying opposite to the

district under the charge of Douglas. The earl, encouraged by the absence

of the Scots king, and still more, by information which led him to believe

that Sir James Douglas was then unprepared and off his guard, resolved, by

an unexpected and vigorous attack, to take this wily and desperate enemy

at an advantage. For this purpose, he collected together, with secrecy and

despatch an army of no less than ten thousand men. Douglas, who had just

then seen completed the erection of his castle or manor house of Lintalee,

near Jedburgh, in which he proposed giving a great feast to his military

followers and vassals, was not, indeed, prepared to encounter a force of

this magnitude; but, from the intelligence of spies whom he maintained in

the enemy’s camp, he was not altogether to be taken by surprise. Aware

of the route by which the English army would advance, he collected, in all

haste, a considerable body of archers, and about fifty men at arms, and

with these took post in an extensive thicket of Jedburgh forest. The

passage or opening through the wood at this place—wide and convenient at

the southern extremity, by which the English were to enter,

narrowed as it approached the ambush, till in breadth it did not exceed a

quoit’s pitch, or about twenty yards. Placing the archers in a hollow

piece of ground, on one side of the pass, Douglas effectually secured them

from the attack of the enemies’ cavalry, by an entrenchment of felled

trees, and by knitting together the branches of the young birch trees with

which the thicket abounded. He himself took post with his small body of

men-at-arms, on the other side of the pass, and there patiently awaited

the approach of the English. These preparations for their

reception having been made with great secrecy and order, the army of

Arundel had no suspicion of the snare laid for them; and, having entered

the narrow part of the defile, seem even to have neglected the ordinary

rules for preserving the proper array of their ranks, these becoming

gradually compressed and confused as the body advanced. In this manner,

unable to form, and, from the pressure in their rear, equally

incapacitated to retreat, the van of the army offered an unresisting and

fatal mark to the concealed archers; who, opening upon them with a volley

of arrows, in front and flank, first made them aware of the danger of

their position, and rendered irremediable the confusion already observable

in their ranks. Douglas, at the same moment, bursting from his ambush, and

raising the terrible war cry of his name, furiously assailed the surprised

and disordered English, a great many of whom, from the impracticability of

their situation, and the impossibility of escape, were slain. Sir James

himself encountered, in this warm onset, a brave foreign knight, named

Thomas de Richemont, whom he slew by a thrust with his dagger; taking from

him, by way of trophy, a furred cap which it was his custom to wear over

his helmet. The English having at length made good their retreat into the

open country, encamped in safety for the night; Douglas, well knowing the

danger he would incur, in following up, with so small a number of men, the

advantage which art and stratagem had so decidedly gained for him.

Had this been otherwise, he

had service of a still more immediate nature yet to perform. Having

intelligence that a body of about three hundred men, under the command of

a person named Ellies, had, by a different route, penetrated to Lintalee,

Sir James hastened thither with all possible expedition. This party,

finding the house deserted and unguarded, had taken possession of it, as

also of the provisions and liquors with which it had been amply provided;

nothing doubting of the complete victory which Arundel would achieve over

Sir James Douglas and his few followers. In this state of security, having

neglected to set watches to apprize them of dangers, they were

unexpectedly assailed by their dreaded and now fully excited enemy, and

mercilessly put to the sword, with the exception of a very few who

escaped. The fugitives having gained the camp of Arundel, that commander

was no less surprised and daunted by this new disaster, than he had been

by that which shortly before befell his own men; so that, finding himself

unequal to the task of dealing with a foe so active and vigilant, he

prudently retreated back into his own country, and disbanded his forces.

Among the other encounters

recorded as having taken place on the borders at this time, we must not

omit one, in which the characteristic and unaided valour of the good Sir

James unquestionably gained for him the victory. Sir Edmund de Cailand, a

knight of Gascony, whom king Edward had appointed governor of Berwick,

desirous of signalizing himself in the service of that monarch, had

collected a considerable force with which he ravaged and plundered nearly

the whole district of Teviot. As he was returning to Berwick, loaded with

spoil, the Douglas, who had intimation of his movements, determined to

intercept his march, and, if possible, recover the booty. For this

purpose, he hastily collected together a small body of troops; but, on

approaching the party of Cailand, he found them so much superior to his

own, in every respect, that he hesitated whether or not he should

prosecute the enterprise. The Gascon knight, confident in his own

superiority, instantly prepared for battle; and a severe conflict ensued,

in which it seemed very doubtful whether the Scots should be able to

withstand the numbers and bravery of their assailants. Douglas, fearful of

the issue of the contest, pressed forward with incredible energy, and,

encountering Sir Edmund de Cailand, slew him with his own hand. The

English party, discouraged by the loss of their leader, and no longer able

to withstand the increased impetuosity with which this gallant deed of Sir

James had inspired his men, soon fell into confusion, and were put to

flight with considerable slaughter. The booty, which, previously to the

engagement, had been sent on towards Berwick, was wholly recovered by the

Scots.

Following upon this

success, and, in some measure connected with it, an event occurred,

singularly illustrative of the chivalric spirit of that age. Sir Ralph

Neville, an English knight who then resided at Berwick, feeling, it may be

supposed, his nation dishonoured, by the praises which the fugitives in

the late defeat bestowed upon the great prowess of Douglas, boastingly

declared, that he would himself encounter that Scottish knight, whenever

his banner should be displayed in the neighbourhood of Berwick. When this

challenge reached the ears of Douglas, he determined that the

self-constituted rival who uttered it, should not want for the opportunity

which he courted. Advancing into the plain around Berwick, Sir James there

displayed his banner, as a counter challenge to the knight, calling upon

him, at the same time, by herald, to make good his bravado. The farther to

incite and irritate the English, he detached a party of his men, who set

fire to some villages within sight of the garrison. Neville, at the head

of a much more numerous force than that of the Scots, at length issued

forth to attack his enemy. The combat was well contested on both sides,

till Douglas, encountering Neville hand to hand, soon proved to that brave

but over-hardy knight, that he had provoked his fate, for he soon fell

under the experienced and strong arm of his antagonist. This event decided

the fortune of the field. The English were completely routed, and several

persons of distinction made prisoners in the pursuit. Taking advantage of

the consternation caused by this victory, Sir James plundered and

desolated with fire all the country on the north side of the river Tweed,

which still adhered to the English interest; and returning in triumph to

the forest of Jedburgh, divided among his followers the rich booty which

he had acquired, reserving no part of it, as was his generous custom, to

his own use.

In the year 1322, the

Scots, commanded by Douglas, invaded the counties of Northumberland and

Durham; but no record now remains of the circumstances attending this

invasion. In the same year, as much by the terror of his name, as by any

stratagem, he saved the abbey of Melrose from the threatened attack of a

greatly superior force of the English, who had advanced against it for the

purposes of plunder. But the service by which, in that last and most

disastrous campaign of Edward II. against the Scots, Sir James most

distinguished himself, was, in the attempt which he made, assisted by

Randolph, to force a passage to the English camp, at Biland, in Yorkshire.

In this desperate enterprise, the military genius of Bruce came

opportunely to his aid, and he proved successful. Douglas, by this action,

may be said to have given a final blow to the nearly exhausted energies of

the weak and misguided government of Edward; and to have thus assisted in

rendering his deposition, which soon after followed, a matter of

indifference, if not of satisfaction to his subjects.

The same active hostility

which had on so many occasions, during the life of our great warrior,

proved detrimental or ruinous to the two first Edwards, was yet to be

exercised with undiminished efficacy upon the third monarch of that name,

the next of the race of English usurpers over Scotland. The treaty of

truce which the disquiets and necessities of his own kingdom had extorted

from Edward II. after his defeat at Biland, having been broken through, as

it would seem, not without the secret connivance or approbation of the

Scottish king; Edward III., afterwards so famous in English history, but

then a minor, collected together an immense force, intending not only to

revenge the infraction, but, by some decisive blow, recover the honour

which his father’s arms had lost in the revolted kingdom. The

inexperience of the young monarch, however, ill seconded as that was by

the councils of the faction which then governed England, could prove no

match, when opposed to the designs of a king so politic as Robert, and the

enterprise and consummate talent of such generals as Randolph and Douglas.

The preparations of

England, though conducted on a great and even extravagant scale of

expense, failed in the despatch essentially necessary on the present

occasion; allowing the Scottish army, which consisted of twenty thousand

light-armed cavalry, nearly a whole month, to plunder and devastate at

will, the northern districts of the kingdom, before any adequate force

could be brought upon the field to oppose their progress. Robert, during

his long wars with England, had admirably improved upon the severe

experience which his first unfortunate campaigns had taught him; and, so

well had the system which he adopted, been inured into the very natures of

his captains and soldiers, by long habit and continued success, that he

could not be more ready to plan and dictate schemes of defence or

aggression, than his subjects were alert and zealous to put them in

execution. He was, besides, fortunate above measure, in the choice of his

generals; and particularly of those two, Randolph, earl of Moray, and Sir

James Douglas, to whose joint command, the army on the present occasion

was committed. Moray, though equally brave and courageous with his

compeer, was naturally guided and restrained by wise and prudential

suggestions; while Douglas, almost entirely under the sway of a sanguine

and chivalrous spirit, often, by his very daring and temerity, proved

successful, where the other must inevitably have failed. One circumstance,

deserving of particular commendation, must not be omitted, that while in

rank and reputation, and in the present instance, command, these two great

men stood, in regard to each other, in a position singularly open to

sentiments of envious rivalry, the whole course of their lives and actions

give ample ground for believing that feelings of such a nature were

utterly alien to the characters of both.

Of the ravages which the

Scottish army committed in the north of England, during the space above

mentioned, we have no particulars recorded, but that they plundered all

the villages and open towns in their route seems certain; prudently

avoiding to dissipate their time and strength by assailing more difficult

places. To atone somewhat for this deficiency in his narrative, Froissart,

who on this period of Scottish history was unquestionably directed by

authentic information, has left a curious sketch of the constitution and

economy of the Scottish army of that day. "The people of that

nation," says this author, "are brave and hardy, insomuch, that

when they invade England, they will often march their troops a distance of

thirty-six miles in a day and night. All are on horseback, except only the

rabble of followers, who are a-foot. The knights and squires are well

mounted on large coursers, or war-horses; but the commons and country

people have only small hackneys or ponies. They use no carriages to attend

their army; and such is their abstinence and sobriety in war, that they

content themselves for a long time with half cooked flesh without bread,

and with water unmixed with wine. When they have slain and skinned the

cattle, which they always find in plenty, they make a kind of kettles of

the raw hides with the hair on, which they suspend on four stakes over

fires, with the hair side outmost, and in these they boil part of the

flesh in water; roasting the remainder by means of wooden spits disposed

around the same fires. Besides, they make for themselves a species

of shoes or brogues of time same raw hides with the hair still on them.

Each person carries attached to his saddle, a large flat plate of iron,

and has a bag of meal fixed on horseback, behind him. When, by eating

flesh cooked as before described, and without salt, they find their

stomachs weakened and uneasy, they mix up some of the meal with water into

a paste; and having heated the flat iron plate on the fire, they knead out

the paste into thin cakes, which they bake or fire on these heated plates.

These cakes they eat to strengthen their stomachs." Such an army

would undoubtedly possess all the requisites adapted for desultory and

predatory warfare; while, like the modern guerillas, the secrecy and

celerity of their movements would enable them with ease and certainty to

elude any formidable encounters to which they might be exposed from troops

otherwise constituted than themselves.

The English army, upon

which so much preparation had been expended, was at length, accompanied by

the king in person, enabled to take the field. It consisted, according to

Froissart, of eight thousand knights and squires, armed in steel, and

excellently mounted; fifteen thousand men at arms, also mounted,

but upon horses of an inferior description; the same number of infantry,

or, as that author has termed them, sergeants on foot; and a body of

archers twenty-four thousand strong. This great force on its progress

northward, soon became aware of the vicinity of their destructive enemy by

the sight of the smoking villages and towns which marked their course in

every direction; but having for several days vainly attempted, by

following these indications, to come up with the Scots, or even to gain

correct intelligence regarding their movements, they resolved, by taking

post on the banks of the river Tine, to intercept them on their return

into Scotland. In this, the English army were not more fortunate; and

having, from the difficulty of their route, been constrained to leave

their camp baggage behind them, they suffered the utmost hardships from

the want of provisions, and the inclemency of the weather. When several

days had been passed in this fruitless and harassing duty, the troops

nearly destitute of the necessaries of life, and exposed, without shelter,

to an almost incessant rain, the king was induced to proclaim a high

reward to whosoever should first give intelligence of where the Scottish

army were to be found. Thomas Rokesby, an esquire, having among others set

out upon this service, was the first to bring back certain accounts that

the Scots lay encamped upon the side of a hill, at about five miles

distance from the English camp. This person had approached so near to the

enemies’ position as to be taken prisoner by the outposts; but he had no

sooner recounted his business to Randolph and Douglas, than he was

honourably dismissed, with orders to inform the English king, that they

were ready and desirous to engage him in battle, whensoever he thought

proper.

On the following day, the

English, marching in order of battle, came in sight of the Scottish army,

whom they found drawn up on foot, in three divisions, on the slope of a

hill; having the river Wear, a rapid and nearly impassable stream, in

front, and their flanks protected by rocks and precipices, presenting

insurmountable difficulties to the approach of an enemy. Edward attempted

to draw them from their fastness, by challenging the Scottish leaders to

an honourable engagement on the plain, a practice not unusual in that age;

but he soon found, that the experienced generals with whom he had to deal

were not to be seduced by any artifice or bravado. "On our road

hither," said they, "we have burnt and spoiled the country; and here

we shall abide while to us it seems good. If the king of England is

offended, let him come over and chastise us." The two armies remained

in this manner, fronting each other, for three days; the army of Edward

much incommoded by the nature of their situation, and the continual alarms

of their hostile neighbours, who, throughout the night, says Froissart,

kept sounding their horns, "as if all the great devils in hell had

been there." Unable to force the Scots to a battle, the English

commanders had no alternative left them, than, by blockading their present

situation, to compel the enemy, by famine, to quit their impregnable

position, and fight at a disadvantage. The fourth morning, however, proved

the futility of such a scheme: for the Scots having discovered a place of

still greater strength at about two miles distance, had secretly decamped

thither in the night. They were soon followed by the English, who took

post on an opposite hill, the river Wear still interposing itself between

the two armies.

The army of Edward, baffled

and disheartened as they had been by the wariness and dexterity of their

enemy, would seem, in their new position, to have relaxed somewhat in

their accustomed vigilance; a circumstance which did not escape the

experienced eye of Sir James Douglas; and which immediately suggested to

the enterprising spirit of that commander, the possibility of executing a

scheme, which, to any other mind, must have appeared wild and chimerical,

as it was hazardous. Taking with him a body of two hundred chosen

horsemen, he, at midnight, forded the river at a considerable distance

from both armies; and by an unfrequented path, of which he had received

accurate information, gained the rear of the English camp undiscovered. On

approaching the outposts, Douglas artfully assumed the manner of an

English officer going his rounds, calling out, as he advanced, "Ha!

St George, you keep no ward here," and, by this stratagem,

penetrated, without suspicion, to the very centre of the encampment, where

the king lay. When they had got thus far, the party, no longer concealing

who they were, shouted aloud, "A Douglas! a Douglas! English thieves,

you shall all die!" and furiously attacking the unarmed and

panic-struck host, overthrew all who came in their way. Douglas, forcing

an entrance to the royal pavilion, would have carried off the young king,

but for the brave and devoted stand made by his domestics, by which he was

enabled with difficulty, to escape. Many of the household, and, among

others, the king’s own chaplain, zealously sacrificed their lives to

their loyalty on this occasion. Disappointed of his prize, Sir James now

sounded a retreat, and charging with his men directly through the camp of

the English, safely regained his own; having sustained the loss of only a

very few of his followers, while that of the enemy is said to have

exceeded three hundred men.

On the day following this

night attack, a prisoner having been brought into the English camp, and

strictly interrogated, acknowledged, that general orders had been issued

to the Scots to hold themselves in readiness to march that evening, under

the banner of Douglas. Interpreting this information by the fears which

their recent surprisal had inspired, the English concluded that the enemy

had formed the plan of a second attack; and in this persuasion, drew up

their whole army in order of battle, and so continued all night resting

upon their arms. Early in the morning, two Scottish trumpeters having been

seized by the patroles, reported that the Scottish army had decamped

before midnight, and were already advanced many miles on their march

homeward. The English could not, for some time, give credit to this

strange and unwelcome intelligence; but, suspecting some stratagem,

continued in order of battle, till, by their scouts, they were fully

certified of its truth. The Scottish leaders, finding that their

provisions were nearly exhausted, had prudently resolved upon a retreat;

and, in the evening, having lighted numerous fires, as was usual, drew off

from their encampment shortly after nightfall. To effect their purpose,

the army had to pass over a morass, which lay in their rear, of nearly two

miles in extent, till then supposed impracticable by cavalry. This passage

the Scots accomplished by means of a number of hurdles, made of wands or

boughs of trees wattled together, employing these as bridges over the

water runs and softer places of the bog; and so deliberately had their

measures been adopted and executed, that when the whole body had passed,

these were carefully removed, that they might afford no assistance to the

enemy, should they pursue them by the same track. Edward is said to have

wept bitterly when informed of the escape of the Scottish army; and his

generals, well aware how unavailing any pursuit after them must prove,

next day broke up the encampment, and retired toward Durham.

This was the last signal

service which Douglas rendered to his country; and an honourable peace

having been soon afterwards concluded between the two kingdoms, seemed at

last to promise a quiet and pacific termination to a life which had

hitherto known no art but that of war, and no enjoyment but that of

victory. However, a different, and to him, possibly, a more enviable fate

awaited the heroic Douglas. Bruce dying, not long after he had witnessed

the freedom of his country established, made it his last request, that Sir

James, as his oldest and most esteemed companion in arms, should carry his

heart to the holy land, and deposit it in the holy sepulchre at Jerusalem,

to the end his soul might be unburdened of the weight of a vow which he

felt himself unable to fulfil.

Douglas, attended by a

numerous and splendid retinue of knights and esquires, set sail from

Scotland, in execution of this last charge committed to his care by his

deceased master. He first touched in his voyage at Sluys in Flanders,

where, having learned that Alphonso, king of Castile and Leon, was then at

waged war with Osmyn, the Moorish king of Granada, he seems to have been

tempted, by the desire of fighting against the infidels, to direct his

course into Spain, with intention, from thence, to combat the Saracens in

his progress to Jerusalem. Having landed in king Alphonso’s country,

that sovereign received Douglas with great distinction; and not the less

so, that he expected shortly to engage in battle with his Moorish enemies.

Barbour relates, that while at this court, a knight of great renown, whose

face was all over disfigured by the scars of wounds which he had received

in battle, expressed his surprise that a knight of so great fame as

Douglas should have received no similar marks in his many combats. "I

thank heaven," answered Sir James, mildly, "that I had always

hands to protect my face." And those who were by, adds the author,

praised the answer much, for there was much understanding in it.

Douglas, and the brave

company by whom he was attended, having joined themselves to Alphonso’s

army, came in view of the Saracens near to Tebas, a castle on the

frontiers of Andalusia, towards the kingdom of Grenada. Osmyn, the Moorish

king, had ordered a body of three thousand cavalry to make a feigned

attack on the Spaniards, while, with the great body of his army, he

designed, by a circuitous route, unexpectedly, to fall upon the rear of

king Alphonso’s camp. That king, however, having received intelligence

of the stratagem prepared for him, kept the main force of his army in the

rear, while he opposed a sufficient body of troops, to resist the attack

which should be made on the front division of his army. From this

fortunate disposition of his forces, the christian king gained the day

over his infidel adversaries. Osmyn was discomfited with much slaughter,

and Alphonso, improving his advantage, gained full possession of the enemy’s

camp.

While the battle was thus

brought to a successful issue in one quarter of the field, Douglas,

and his brave companions, who fought in the van, proved themselves no less

fortunate. The Moors, not long able to withstand the furious encounter of

their assailants, betook themselves to flight. Douglas, unacquainted with

the mode of warfare pursued among that people, followed hard after the

fugitives, until, finding himself almost deserted by his followers, he

turned his horse, with the intention of rejoining the main body. Just

then, however, observing a knight of his own company to be surrounded by a

body of Moors, who had suddenly rallied, "Alas," said he,

"yonder worthy knight shall perish, but for present help;" and

with the few who now attended him, amounting to no more than ten men, he

turned hastily, to attempt his rescue. He soon found himself hard pressed

by the numbers who thronged upon him. Taking from his neck the silver

casquet which contained the heart of Bruce, he threw it before him among

the thickest of the enemy, saying, "Now pass thou onward before us,

as thou wert wont, and I will follow thee or die." Douglas, and

almost the whole of the brave men who fought by his side, were here slain.

His body and the casquet containing the embalmed heart of Bruce were found

together upon the field; and were, by his surviving companions, conveyed

with great care and reverence into Scotland. The remains of Douglas were

deposited in the family vault at St Bride’s chapel, and the heart of

Bruce solemnly interred by Moray, the regent, under the high altar of

Melrose Abbey.

So perished, almost in the prime of his

life, the gallant, and, as his grateful countrymen long affectionately

termed him, "the good Sir James Douglas," having survived little

more than one year, the demise of his royal master. His death was soon

after followed by that of Randolph; with whom might be said to close the

race of illustrious men who had rendered the epoch of Scotland’s

renovation and independence so remarkable.

Pictures are the copyright of

Patrick Hickey

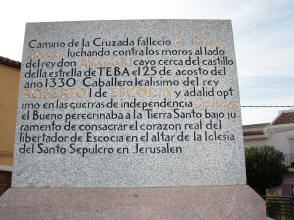

The place where Douglas finally died was

during the battle of Teba, a small town in Andalusia, on August 25th 1330.

In the towns Plaza Espana there is erected a big granite stone in his

memory. One side of this stone is in Spanish and the other side in

English.

(Thanks to Patrick for sending us this note and these pictures.)

Note

"The statement of Chalmers (Caledonia, I, p 579) that the Douglases sprang

from Theobaldus the Fleming, who obtained a grant of lands on the Douglas

Water from the Abbot of Kelso is generally discredited. The lands granted

by the abbot to Theobald the Fleming between 1147 and 1160, though on the

Douglas Water, were not a part of the ancient territory of Douglas, and

there is no proof nor even any probability that William de Duglas of the

12th century is descended from the Fleming who settled on the opposite

side of his native valley." (The Surnames of Scotland, 1946, George F.

Black, p. 218) |