|

In the year 1787 four new regiments were

ordered to be raised for the service of the

state, to be numbered the 74th, 75th, 76th, and 77th. The first two were

directed to be raised in the north of Scotland, and were to be Highland

regiments. The regimental establishment of each was to consist of ten companies

of 75 men each, with the customary number of commissioned and non-commissioned

officers. Major-General Sir Archibald Campbell, K.B., from the half-pay of

Fraser’s Highlanders, was appointed colonel of the

74th regiment. In the year 1787 four new regiments were

ordered to be raised for the service of the

state, to be numbered the 74th, 75th, 76th, and 77th. The first two were

directed to be raised in the north of Scotland, and were to be Highland

regiments. The regimental establishment of each was to consist of ten companies

of 75 men each, with the customary number of commissioned and non-commissioned

officers. Major-General Sir Archibald Campbell, K.B., from the half-pay of

Fraser’s Highlanders, was appointed colonel of the

74th regiment.

The establishment of the regiment was

fixed as ten companies, consisting

of—.

I Colonel and Captain. 1 Adjutant.

1 Lieutenant-Colonel and 1 Quartermaster.

Captain. 1 Surgeon.

1 Major and Captain. 2 Surgeon’s Mates.

7 Captains. 80 Sergeants.

1 Captain-Lieutenant. 40 Corporals.

21 Lieutenants. 20 Drummers.

8 Ensigns. 2 Fifers, and

1 Chaplain. 710 Privates.

A

recruiting company was afterwards added, which

consisted of—

1

Captain. 8 Corporals.

2 Lieutenants. 4 Drummers.

1 Ensign. 80 Privates.

8 Sergeants.

Total of Officers and Men of all ranks, 902.

The regiment was styled "The 74th Highland

Regiment of Foot." The uniform

was the full Highland garb of kilt and feathered bonnet, the

tartan being similar to that of the 42nd regiment, and the facings white; the

use of the kilt was, however, discontinued in the East Indies, as being unsuited

to the climate.

The following were the officers first appointed to the

regiment:—

Colonel—Archibald

Campbell, K.B.

Lieutenant-Colonel—Gordon

Forbes.

Captains.

Dugald Campbell. William

Wallace.

Alexander Campbell. Robert Wood.

Archibald Campbell.

Captain-Lieutenant and Captain—Heneage

Twysden.

Lieutenants.

James Clark. John Alexander.

Charles Campbell. Samuel Swinton.

John Campbell. John Campbell.

Thomas Carnie. Charles Campbell.

W. Coningsby Davies. George Henry Vansittart

Dugald Lamont. Archibald

Campbell.

Ensigns

John Forbes. John Wallace.

Alexander Stewart. Hugh M’Pherson.

James Campbell.

Chaplain—John

Ferguson.

Adjutant—Samuel

Swinton.

Quartermaster—James

Clark.

Surgeon—William

Henderson.

As the state of affairs in India

required that reinforcements should be immediately

despatched to that country, all the men who had been embodied previous to

January 1788 were ordered for embarkation, without waiting for the fall

complement. In consequence of these orders, 400 men, about one-half Highlanders,

embarked at Grangemouth, and sailed from Chatham for the East Indies, under the

commend of Captain William Wallace. The regiment

having been completed in autumn, the recruits followed in February 1789, and arrived

at Madras in June in perfect health. They joined the first detachment at the

cantonments of Poonamallee, and thus united, the corps amounted to 750 men.

These were now trained under Lieutenant-Colonel Maxwell, who had succeeded

Lieutenant-Colonel Forbes in the command, and who had acquired some experience

in the training of soldiers as captain in Fraser’s Highlanders.

In connection with the main army under

Lord Cornwallis, the Madras army under General Meadows, of which the 74th formed

a part, began a series of movements in the spring of 1790. The defence of the

passes leading into

the Carnatic from Mysore was intrusted to Colonel Kelly, who, besides his own

corps, had under him the 74th; but he dying in September, Colonel Maxwell [This

able officer was son of Sir William Maxwell of Monreith, and brother of the

Duchess of Gordon. He died at Cuddalore in 1783] succeeded to the command.

The 74th was put in brigade with the 71st

and 72nd Highland regiments. The regiment suffered no loss in the different

movements which took place till the storming of Bangalore, on the 21st of March

1791. The whole loss of the British, however, was only 5 men. After the defeat

of Tippoo Sahib at Seringapatam, on the 15th of May 1791, the army, in

consequence of bad weather and scarcity of provisions, retreated upon

Bangalore, reaching that

place in July.

The 74th was detached from the army at

Nundeedroog on the 21st of October, with three Sepoy battalions and some field

artillery, under Lieutenant-Colonel Maxwell,

into the Baramahal country, which this column was

ordered to clear of the enemy. They reached the south end of the valley by

forced marches, and took the strong fort of Penagurh by escalade on the 31st of

October, and after scouring the whole of the Baramahal to the southward,

returned towards Caverypooram, and encamped within five miles of the strong fort

of Kistnagherry, 50 miles S.E. of Bangalore, on the 7th of November.

Lieutenant-Colonel Maxwell determined on attacking the lower fort and town

immediately, and the column advanced from the camp to the attack in three

divisions at ten o’clock on that night; two of these were sent to the right and

left to attack the lower fort on the western and eastern sides, while the centre

division advanced directly towards the front wall. The divisions approached

close to the walls before they were discovered, succeeded in escalading them,

and got possession of the gates. The enemy fled to the upper fort without making

much resistance, and the original object of the attack was thus gained. But a

most gallant attempt was made by Captain Wallace of the 74th, who commanded the

right division, to carry the almost inaccessible upper fort also. His division

rushed up in pursuit of the fugitives; and notwithstanding the length and

steepness of the ascent, his advanced party followed the enemy so closely that

they had barely time to shut the gates. Their standard was taken on the steps of

the gateway; but as the ladders had not been brought forward in time, it was

impossible to escalade before the enemy recovered from their panic.

During two hours, repeated trials were

made to get the ladders up, but the enemy hurling down showers of rocks and

stones into the road, broke the ladders, and crushed those who carried them.

Unluckily, a clear moonlight discovered every movement, and at length, the

ladders being all destroyed, and many officers and men disabled in carrying

them, Lieutenant-Colonel Maxwell found it necessary to order a discontinuance of

the assault.

The retreat of the men who had reached the

gate, and of the rest of the troops, was conducted with such regularity, that a

party which sallied from the fort in pursuit of them was immediately driven

back. The pettah, or lower town, was set fire

to, and the troops withdrawn to their camp before

daylight on the 8th of November.

The following were the casualties in the

regiment on this occasion :—Killed, 2 officers, 1 sergeant, 5

rank and file; wounded, 3

officer; 47 non-commissioned officers and men. The officers killed were

Lieutenants Forbes and Lamont; those wounded, Captain Wallace, Lieutenants

M’Kenzie and Aytone.

The column having also reduced several

small forts in the district of Ossoor, rejoined the

army on the 30th of

November.

In the second attempt on Seringapatam, on

the 6th of February 1792, the 74th, with the 52nd regiment and 71st Highlanders,

formed the centre under the immediate orders of the Commander-in-Chief. Details

of these operations, and others elsewhere in India, in which the 74th took part

at this time, have already been given in our accounts of the 71st and 72nd

regiments. The 74th on this occasion had 2 men killed, and Lieutenant Farquhar,

Ensign Hamilton, and 17 men wounded.

On the termination of hostilities this

regiment returned to the coast. In July 1793 the flank companies were embodied

with those of the 71st in the expedition against Pondicherry. The following

interesting episode, as related in Cannon’s account of the regiment, occurred

after the capture of Pondicherry:-

The 74th formed

part of the garrison, and

the French troops remained in the place as prisoners of war. Their officers were

of the old régime, and were by birth and in manners gentlemen, to whom it

was incumbent to show every kindness and hospitality. It was found, however,

that both officers and men, and the French population generally, were strongly

tinctured with the revolutionary mania, and some uneasiness was felt lest the

same should be in any degree imbibed by the British soldiers. It happened that

the officers of the 74th were in the theatre, when a French officer called for

the revolutionary air, "Cą Ira;" this was opposed by some of the

British, and there was every appearance of a serious disturbance, both parties

being highly excited. The 74th, being in a body, had an opportunity to consult,

and to act with effect. Having taken their resolution, two or three of them made

their way to the orchestra, the rest taking post at the doors, and, having

obtained silence, the senior officer addressed the house in a firm but

conciliatory manner. He stated that the national tune called for by one of the

company ought not to be objected to, and that, as an act of courtesy to the

ladies and others who had seconded the request, he and his brother officers were

determined to support it with every mark of respect, and called upon their

countrymen to do the same. It was accordingly played with the most uproarious

applause on the part of the French, the British officers standing up uncovered;

but the moment it was finished, the house was called upon by the same party

again to uncover to the British national air, "God save the King." They now

appealed to the French, reminding them that each had their national attachments

and recollections of home; that love of country was an honourable principle, and

should be respected in each other; and that they felt assured their respected

friends would not be behind in that courtesy which had just been shown by the

British. Bravo! Bravo! resounded from every part of the house, and from that

moment all rankling was at an end. They lived in perfect harmony till the French

embarked, and each party retained their sentiments as a thing peculiar to their

own country, but without the slightest offence on either side, or expectation

that they should assimilate, more than if they related to the colour of their

uniforms. As a set-off to this, it

is worth recording that in 1798, when

voluntary contributions for them support of the war with France were being

offered to Government from various parts of the British dominions, the privates

of the 74th, of their own accord, handsomely and patriotically contributed eight

days’ pay to assist in carrying on the war,—" a war," they said, "unprovoked on

our part, and justified by the noblest of motives, the

preservation of our individual constitution." The sergeants

and corporals, animated by similar sentiments, subscribed a fortnight’s, and the

officers a month’s pay each.

Besides reinforcements of recruits from

Scotland fully sufficient to compensate all casualties, the regiment received,

on the occasion of the 71st being ordered home to Europe,

upwards of

200 men from that regiment. By these additions the strength of the 74th was kept

up, and the regiment, as well in the previous campaign as in the subsequent one

under General Harris, was one of the most effective in the field.

The 74th was concerned in all the operations of this

campaign, and had its full share in the

storming of

Seringapatam on the 4th of May 1799.

The troops for the assault, commanded by

Major-General Baird, were divided into

two columns of attack. The 74th, with the 73rd regiment, 4 European flank

companies, 14 Sepoy flank companies, with 50 artillerymen, formed the right

column, under Colonel Sherbroke. Each column was preceded by 1 sergeant and 12

men, volunteers, supported by an advanced party of 1 subaltern and 25 men.

Lieutenant Hill, of the 74th, commanded the advanced party of the right column.

After the successful storm and capture

of the fortress, the 74th was the first regiment that entered the palace.

The casualties of the regiment during the

siege were :—Killed, 5 officers, and 45 non commissioned officers and men.

Wounded, 4 officers, and 111 non-commissioned officers and men. Officers killed,

Lieutenants Irvine, Farquhar, Hill, Shaw, Prendergast. Officers wounded,

Lieutenants Fletcher, Aytone, Maxwell, Carrington.

The regiment received the royal authority

to bear the word "Seringapatam" on its regimental colour and appointments in

commemoration of its services at this siege.

The 74th had not another opportunity of

distinguishing itself till the year 1803, when three occasions occurred. The

first was on the 8th of August, when the fortress of Ahmednuggur, then in

possession of Sindiah, the Mahratta chief, was attacked, and carried by assault

by the army detached under the Hon. Major-General Sir Arthur Wellesley. In this

affair the 74th, which formed a part of the brigade commanded by Colonel

Wallace, bore a distinguished part, and gained the special thanks of the

Major-General and the Governor-General.

The next was the battle of Assaye, fought

on the 23rd of September. On that day Major-General the Hon. Arthur Wellesley

attacked the whole combined Mahratta army of Sindiah and the Rajah of Berar, at

Asssya, on the banks of the Kaitna river. The Mahratta force, of 40,000 men, was

completely defeated by a force of 5000, of which not more than 2000 were

Europeans, losing 98 pieces of cannon, 7 standards, and leaving 1200 killed, and

about four times that number wounded on the field. The conduct of the 74th in

this memorable battle was most gallant and distinguished; but from having been

prematurely led against the village of Assaye on the left of the enemy’s line,

the regiment was exposed, unsupported, to a most terrible cannonade, and being

afterwards charged by cavalry, sustained a tremendous loss.

In this action, the keenest ever fought in

India, the 74th had Captains D. Aytone, Andrew Dyce, Roderick Macleod, John

Maxwell; Lieutenants John Campbell, John Morshead Campbell, Lorn Campbell, James

Grant, J. Morris, Robert Neilson, Volunteer Tew, 9 sergeants, and 127 rank and

file killed; and Major Samuel Swinton, Captains Norman Moore, Matthew Shawe,

John Alexander Main, Robert Macmurdo, J. Longland, Ensign Kearnon, 11 sergeants,

7 drummers, and 270 rank and file wounded. "Every officer present," says Cannon,

"with the regiment was either killed or wounded, except Quartermaster James

Grant, who, when he saw so many of his friends fall in the battle, resolved to

share their fate, and, though a non-combatant, joined the ranks and fought to

the termination of the action." Besides expressing his indebtedness to the 74th

in his despatch to the Governor-General, Major-General Wellesley added the

following to his memorandum on the battle :— "However, by one of those unlucky

accidents which frequently happen, the officer commanding the piquets which were

upon the right led immediately up to the village of Assays. The 74th regiment,

which was on the right of the second line, and was ordered to support the

piquets, followed them. There was a large break in our line between these corps

and those on our left. They were exposed to a most terrible cannonade from

Assaye, and were charged by the cavalry belonging to the Campoos; consequently

in the piquets and the 74th regiment we sustained the greatest part of our loss.

"Another bad consequence resulting from

this mistake was the necessity of introducing the cavalry into the action at too

early a period. I had ordered it to watch the motions of the enemy’s cavalry

hanging upon our right, and luckily it charged in time to save the remains of

the 74th and the piquets."

The names especially of

Lieutenants-Colonel Harness and Wallace were mentioned with high approbation

both by Wellesley and the Governor-General. The Governor-General ordered that

special honorary colours be presented to the 74th and 78th, who were the only

European infantry employed "on that glorious occasion," with a device suited to

commemorate the signal and splendid victory.

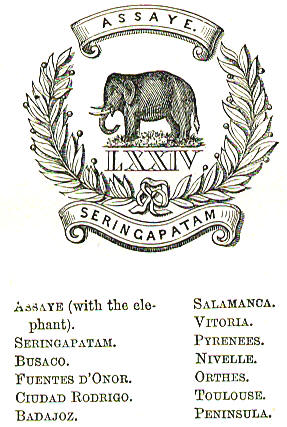

The device on the special colour awarded

to the 74th appears at the head of this account. The 78th for some reason ceased

to make use of its third colour after it left India, so that the 74th is now

probably the only regiment in the British army that possesses such a colour, an

honour of which it may well be proud.

Captain A. B. Campbell of the 74th, who

had on a former occasion lost an arm, and had afterwards had the remaining one

broken at the wrist by a fall in hunting, was seen in the thickest of the action

with his bridle in his teeth, and a sword in his mutilated hand, dealing

destruction around him. He came off unhurt, though one of the enemy in the

charge very nearly transfixed him with a bayonet, which actually pierced his

saddle.

The third occasion in 1803 in which the

74th was engaged was the battle of Argaum, which was gained with little loss,

and which fell chiefly on the 74th and 78th regiments, both of which were

specially thanked by Wellesley. The 74th had 1 sergeant and 3 rank and file

killed, and 1 officer, Lieutenant Langlands, [A powerful Arab threw a spear at

him, and, drawing his sword, rushed forward to finish the lieutenant. But the

spear having entered Langland’s leg, cut its way out again, and stuck in the

ground behind him. Langlands grasped it, and, turning the point, threw it with

so true an aim, that it went right through his opponent’s body, and transfixed

him within three or four yards of his intended victim. All eyes were for an

instant turned on these two combatants, when a Sepoy rushed out of the ranks,

and patting the lieutenant on the back, exclaimed, "Atcha Sahib! Chote atcha

keeah!" " Well Sir! very well done." Such a ludicrous circumstance, even in a

moment of such extreme peril, raised a very hearty laugh among the

soldiers.—Welsh’s "Military Reminiscences," vol. i. p. 194.] 5 sergeants, 1

drummer, and 41 rank and file wounded.

Further details of these three important

affairs will be found in the history of the 78th regiment.

In September 1805, the regiment, having

served for sixteen years in India, embarked for England, all the men fit for

duty remaining in India.

The following Order in Council was issued

on the occasion by the Governor, Lord William Bentinck:-

"Fort St George, 5th Sept. 1805.

"The Right Honourable the Governor in

Council, on the intended embarkation of the remaining officers and men of His

Majesty’s 74th regiment, discharges a duty of the highest satisfaction to his

Lordship in Council in bestowing on that distinguished corps a public testimony

of his Lordship’s warmest respect and approbation. During a long and eventful

period of residence in India, the conduct of His Majesty’s 74th regiment,

whether in peace or war, has been equally exemplary and conspicuous, having been

not less remarkable for the general tenor of its discipline than for the most

glorious achievements in the field.

"Impressed with these sentiments, his

Lordship in Council is pleased to direct that His Majesty’s 74th regiment be

held forth as an object of imitation for the military establishment of this

Presidency, as his Lordship will ever reflect with pride and gratification, that

in the actions which have led to the present pre-eminence of the British Empire

in India, the part so nobly sustained by that corps will add lustre to the

military annals of the country, and crown the name of His Majesty’s 74th

regiment with immortal reputation.

"It having been ascertained, to the

satisfaction of the Governor in Council, that the officers of His Majesty’s 74th

regiment were, during the late campaign in the Deccan, subjected to

extraordinary expenses, which have been aggravated by the arrangements connected

with their embarkation for Europe, his Lordship in Council has been pleased to

resolve that those officers shall receive a gratuity equal to three months’

batta, as a further testimony of his Lordship’s approbation of their eminent

services.

"By order of the Right Honourable the

Governor in Council.

"J. H. WEBB,

"Secretary to the Government.

Besides the important engagements in which

the 74th took part during its long stay in India, there were many smaller

conflicts and arduous services which devolved upon the regiment, but of which no

record has been preserved. Some details illustrative of these services are

contained in Cannon’s history of the 74th, communicated by officers who served

with it in India, and afterwards throughout the Peninsular War. Captain Cargill,

who served in the regiment, writes as follows:—

"The 74th lives in my recollection under

two aspects, and during two distinct epochs.

"The first is the history and character of

the regiment, from its formation to its return as a skeleton from India; and the

second is that of the regiment as it now exists, from its being embarked for the

Peninsula in January 1810.

"So far as field service is concerned, it

has been the good fortune of the corps to serve during both periods, on the more

conspicuous occasions, under the great captain of the age; under him also,

during the latter period, it received the impress of that character which

attaches to most regiments that were placed in the same circumstances, which

arose from the regulations introduced by His Royal Highness the Duke of York,

and the practical application of them by a master mind in the great school of

the Peninsular War. Uniformity was thus given; and the 74th, like every other

corps that has had the same training, must acknowledge the hand under which its

present character was mainly impressed. But it was not so with the 74th in

India. At that time every regiment had its distinctive character and system

broadly marked, and this was generally found to have arisen from the materials

of which it had been originally composed, and the tact of the officer by whom it

had been embodied and trained. The 74th, in these respects, had been fortunate,

and the tone and discipline introduced by the late Sir Archibald Campbell,

together with the chivalrous spirit and noble emulation imbibed by the corps in

these earlier days of Eastern conquest, had impressed upon the officers the most

correct perception of their duties, not only as regards internal economy and the

gradation of military rank, but also as regards the Government under which they

served. It was, perhaps, the most perfect that could well exist. It was

participated in by the men, and certainly characterised the regiment in a strong

degree.

"It was an established principle in the

old 74th, that whatever was required of the soldier should be strikingly set

before him by his officers, and hence the most minute point of ordinary duty was

regarded by the latter as a matter in which his honour was implicated. The duty

of the officer of the day was most rigidly attended to, the officer on duty

remaining in full uniform, and without parting with his sword even in the

hottest weather, and under all circumstances, and frequently going the rounds of

the cantonments during the night. An exchange of duty was almost never heard of,

and the same system was carried into every duty and department, with the most

advantageous effect upon the spirit and habits of the men.

"Intemperance was an evil habit fostered

by climate and the great facility of indulgence but it

was a point of honour

among the men never to indulge when near an enemy, and I often heard it

observed, that this rule was never known to be broken, even under the protracted

operations of a siege. On such occasions the officers had no trouble with it,

the principle being upheld by the men themselves.

"On one occasion, while the 74th was in

garrison at Madras, and had received a route to march up the country, there was

a mutiny among the Company’s artillery at the Mount. The evening before the

regiment set out it was reported that they had some kind of leaning towards the

mutineers; the whole corps felt most indignant at the calumny, but no notice was

taken of it by the commanding officer. In the morning, however, he marched

early, and made direct for the Mount, where he unfurled the colours, and marched

through the cantonments with fixed bayonets. By a forced march he reached his

proper destination before midnight, and before dismissing the men, he read them

a short but pithy despatch, which he sent off to the Government, stating the

indignation of every man of the corps at the libelous rumour, and that he had

taken the liberty of gratifying his men by showing to the mutineers those

colours which were ever faith fully devoted to the service of the Government.

The circumstance had also a happy effect upon the mutineers who had heard the

report, but the stern aspect of the regiment dispelled the illusion, and they

submitted to their officers."

The losses sustained by the regiment in

officers and men, on many occasions, of which no account has been kept, were

very great, particularly during the last six years of its Indian service.

That gallant veteran, Quarter-master

Grant, who had been in the regiment from the time it was raised, fought at

Assaye, and returned with it to England, used to say that he had seen nearly

three different sets of officers during the period, the greater part of whom had

fallen in battle or died of wounds, the regiment having been always very

healthy.

Before the 74th left India, nearly all the

men who were fit for duty volunteered into other regiments that remained on

service in that country. One of these men, of the grenadier company, is said to

have volunteered on nine forlorn hopes, including Seringapatam.

The regiment embarked at Madras in

September 1805, a mere skeleton so far as numbers were concerned, landed at

Portsmouth in February 1806, and proceeded to Scotland to recruit, having

resumed the kilt, which had been laid aside in India. The regiment was stationed

in Scotland (Dumbarton Castle, Glasgow, and Fort-George), till January

1809, but did not manage to recruit to within 400 men of its complement, which

was ordered to be completed by volunteers from English and Irish, as well as

Scotch regiments of militia. The regiment left Scotland for Ireland in January

1809, and in May of that year it was ordered that the Highland dress of the

regiment should be discontinued, and its uniform assimilated to that of English

regiments of the line; it however retained the designation Highland until

the year 1816, and, as will be seen, in 1846 it was permitted to resume the

national garb, and recruit only in Scotland. For these reasons we are justified

in continuing its history to the present time.

It was

while in Ireland, in September 1809, that

Lieutenant-Colonel Le Poer Trench, whose name will ever be remembered in

connection with the 74th, was appointed to the command of the regiment, from

Inspecting Field-Officer in Canada, by exchange with Lieutenant-Colonel Malcolm

Macpherson; the latter having succeeded that brave officer, Lieutenant-Colonel

Swinton, in 1805.

In January 1810 the regiment sailed from

Cork for the Peninsula, to take its share in the warlike operations going on

there, landing at Lisbon on February 10. On the 27th the 74th set out to join

the army under Wellington, and reached Vizeu on the 6th of March. While at Vizeu,

Wellington inquired at Colonel Trench how many of the men who fought at Assaye

still remained in the regiment, remarking that if the 74th would behave in the

Peninsula as they had done in India, he ought to be proud to command such a

regiment. Indeed the "Great Duke" seems to have had an exceedingly high estimate

of this regiment, which he took occasion to show more than once. It is a curious

fact that the 74th had never more than one battalion; and when, some time before

the Duke’s death, "Reserve Battalions" were formed to a few regiments. He

decided "that the 74th should not have one, as they got through the Peninsula

with one battalion, and their services were second to none in the army."

The regiment was placed in the 1st brigade

of the 3rd division, under Major-General Picton, along with the 45th, the 88th,

and part of the 60th Regiment. This division performed such a distinguished part

in all the Peninsular operations, that it earned the appellation of the

"Fighting Division." We of course cannot enter into the general details of the

Peninsular war, as much of the history of which as is necessary for our purpose

having been already given in our account of the 42nd regiment.

The first action in which the 74th had a

chance of taking part was the battle of Busaco, September 27, 1810. The allied

English and Portuguese army numbered 50,000, as opposed to Marshal Massena’s

70,000 men. The two armies were drawn upon opposite ridges, the position of the

74th being across the road leading from St Antonio de Cantara to Coimbra. The

first attack on the right was made at six o’clock in the morning by two columns

of the French, under General Regnier, both of which were directed with the usual

impetuous rush of French troops against the position held by the 3rd division,

which was of comparatively easy ascent. One of these columns advanced by the

road just alluded to, and was repulsed by the fire of the 74th, with the

assistance of the 9th and 21st Portuguese regiments, before it reached the

ridge. The advance of this column was preceded by a cloud of skirmishers, who

came up close to the British position, and were picking off men, when the two

right companies of the regiment were detached, with the rifle companies

belonging to the brigade, and drove back the enemy’s skirmishers with great

vigour nearly to the foot of the sierra. The French, however, renewed the attack

in greater force, and the Portuguese regiment on the left being thrown into

confusion, the 74th was placed in a most critical position, with its left flank

exposed to the overwhelming force of the enemy. Fortunately, General Leith,

stationed on another ridge, saw the danger of the 74th, and sent the 9th and

38th regiments to its support. These advanced along the rear of the 74th in

double quick time, met the head of the French column as it crowned the ridge,

and drove them irresistibly down the precipice. The 74th then advanced with the

9th, and kept up a fire upon the enemy as long as they could be reached. The

enemy having relied greatly upon this attack, their repulse contributed

considerably to their defeat. The 74th had Ensign Williams and 7 rank and file

killed, Lieutenant Cargilland 19 rank and file wounded. The enemy lost 5000

killed and wounded.

The allies, however, retreated from their

position at Busaco upon the lines of Tones Vedras, an admirable series of

fortifications contrived for the defence of Lisbon, and extending from the Tagus

to the sea. The 74th arrived there on the 8th of October, and remained till the

middle of December, living comfortably, and having plenty of time for amusement.

The French, however, having taken up a strong position at Santarem, an advanced

movement was made by the allied army, the 74th marching to the village of

Togarro about the middle of December, where it remained till the beginning of

March 1811, suffering much discomfort and hardship from the heavy rains, want of

provisions, and bad quarters. The French broke up their position at Santarem on

the 5th of March, and retired towards Mondego, pursued by the allies. On the

12th, a division under Ney was found posted in front of the village of Redinha,

its flank protected by wooded heights. The light division attacked the height on

the right of the enemy, while the third division attacked those on the left, and

after a sharp skirmish the enemy retired across the Redinha river. The 74th had

1 private killed, and Lieutenant Crabbie and 6 rank and file wounded. On the

afternoon of the 15th of March the third and light divisions attacked the French

posted a Foz de Arouce, and dispersed their left and centre, inflicting great

loss. Captain Thomson and 11 rank and file of the 74th were wounded in this

affair.

The third division was constantly in

advance of the allied forces in pursuit of the enemy, and often suffered great

privations from want of provisions, those intended for it being appropriated by

some of the troops in the rear. During the siege of Almeida the 74th was

continued at Nave de Aver, removing on the 2nd of May to the rear of the village

of Fuentes d’Onor, and taking post on the right of the position occupied by the

allied army, which extended for about five miles along the Dos Casas river. On

the morning of the 3rd of May the first and third divisions were concentrated on

a gentle rise, a cannon-shot in rear of Fuentes d’Onor. Various attacks and

skirmishes occurred on the 3rd and 4th, and several attempts to occupy the

village were made by the French, who renewed their attack with increased force

on the morning of the 5th May. After a hard fight for the possession of the

village, the defenders, hardly pressed, were nearly driven out by the superior

numbers of the enemy, when the 74th were ordered up to assist. The left wing,

which advanced first, on approaching the village, narrowly escaped being cut off

by a heavy column of the enemy, which was concealed in a lane, and was observed

only in time to allow the wing to take cover behind some walls, where it

maintained itself till about noon. The right wing then joined the left, and with

the 71st, 79th, and other regiments, charged through and drove the enemy from

the village, which the latter never afterwards recovered. The 74th on this day

lost Ensign Johnston, 1 sergeant, and 4 rank and file, killed; and Captains

Shawe, M’Queen, and Adjutant White, and 64 rank and file, wounded.

The 74th was next sent to take part in the

siege of Badajos, where it remained from May 28 till the middle of July, when it

marched for Albergaria, where it remained till the middle of September, the

blockade of Ciudad Rodrigo in the meantime being carried on by the allied army.

On the 17th of September the 74th advanced to El Bodon on the Agueda, and on the

22nd to Pastores, within three miles of Ciudad Rodrigo, forming, with the three

companies of the 60th, the advanced guard of the third division. On the 25th,

the French, under General Montbrun, advanced thirty squadrons of cavalry,

fourteen battalions of infantry, and twelve guns, direct upon the main body of

the third division at El Bodon, and caused it to retire, surrounded and

continually threatened by overwhelming numbers of cavalry, over a plain of six

miles, to Guinaldo.

The 74th, and the companies of the 60th,

under Lieut.-Colonel Trench, at Pastores, were completely cut off from the rest

of the division by the French advance, and were left without orders; but they

succeeded in passing the Agueda by a ford, and making a very long detour through

Robledo, where they captured a party of French cavalry, recrossed the Agueda,

and joined the division in bivouac near Fuente Guinaldo, at about two o’clock on

the morning of the 26th. It was believed at headquarters that this detachment

had been all captured, although Major-General Picton, much pleased at their safe

return, said he thought he must have heard more firing before the 74th could be

taken. After a rest of an hour or two, the regiment was again under arms, and

drawn up in position at Guinaldo before daybreak, with the remainder of the

third and the fourth division. The French army, 60,000 strong, being united in

their front, they retired at night about twelve miles to Alfayates. The regiment

was again under arms at Alfayates throughout the 27th, during the skirmish in

which the fourth division was engaged at Aldea de Pouts. On this occasion the

men were so much exhausted by the continued exertions of the two preceding days,

that 125 of them were unable to remain in the ranks, and were ordered to a

village across the Coa, where 80 died of fatigue. This disaster reduced the

effective strength of the regiment below that of 1200, required to form a second

battalion, which had been ordered during the previous month, and the requisite

strength was not again reached during the war.

The 74th was from the beginning of October

mainly cantoned at Aides de Ponte, which it left on the 4th of January 1812, to

take part in the siege of Rodrigo. The third division reached Zamora on the 7th,

five miles from Rodrigo, where it remained during the siege. The work of the

siege was moat laborious and trying, and the 74th had its own share of

trench-work. The assault was ordered for the 19th of January, when two breaches

were reported practicable.

The assault of the great breach was

confided to Major-General M’Kinnon’s brigade, with a storming party of 500

volunteers under Major Manners of the 74th, with a forlorn hope under Lieutenant

Mache of the 88th regiment. There were two columns formed of the 5th and 94th

regiments ordered to attack and clear the ditch and fausse-braie on the

right of the great breach, and cover the advance of the main attack by General

M’Kinnon’s brigade. The light division was to storm the small breach on the

left, and a false attack on the gate at the opposite side of the town was to be

made by Major-General Pack’s Portuguese brigade.

Immediately after dark, Major-General

Picton formed the third division in the first parallel and approaches, and lined

the parapet of the second parallel with the 83rd Regiment, in readiness to open

the defences. At the appointed hour the attack commenced on the side of the

place next the bridge, and immediately a heavy discharge of musketry was opened

from the trenches, under cover of which 150 sappers, directed by two engineer

officers, and Captain Thomson of the 74th Regiment, advanced from the second

parallel to the crest of the glacis, carrying bags filled with hay, which they

threw down the counterscarp into the ditch, and thus reduced its depth from 134

to 8 feet. They then fixed the ladders, and General M’Kinnon’s brigade, in

conjunction with the 5th and 94th Regiments, which arrived at the same moment

along the ditch from the right, pushed up the breach, and after a sharp struggle

of some minutes with the bayonet, gained the summit. The defenders then

concentrated behind the retrenchment, which they obstinately retained, and a

second severe struggle commenced. Bags of hay were thrown into the ditch, and as

the counterscarp did not exceed 11 feet in depth, the men readily jumped upon

the bags, and without much difficulty carried the little breach. The division,

on gaining the summit, immediately began to form with great regularity, in order

to advance in a compact body and fall on the rear of the garrison, who were

still nobly defending the retrenchment of the great breach. The contest was

short but severe; officers and men fell in heaps, as Cannon puts it, killed and

wounded, and many were thrown down the scarp into the main ditch, a depth of 30

feet; but by desperate efforts directed along the parapet on both flanks, the

assailants succeeded in turning the retrenchments. The garrison then abandoned

the rampart, having first exploded a mine in the ditch of the retrenchment, by

which Major-General M'Kinnon and many of the bravest and most forward perished

in the moment of victory. General Vandeleur’s brigade of the light division had

advanced at the same time to the attack of the lesser breach on the left, which,

being without interior defence, was not so obstinately disputed, and the

fortress was won.

In his subsequent despatch Wellington

mentioned the regiment with particular commendation, especially naming Major

Manners and Captain Thomson of the 74th, the former receiving the brevot of

Lieutenant-Colonel for his services on this occasion.

During the siege the regiment lost 6 rank

and file killed, and Captains Langlands and Collins, Lieutenants Tew and Ramadge,

and Ensign Atkinson, 2 sergeants, and 24 rank and file, killed.

Preparations having been made for the

siege of Badajo; the 74th was sent to that place, which it reached on the 16th

of March (1812), taking its position along with the other regiments on the

south-east side of the town. On the 19th the garrison made a sortie from behind

the Picurina with 1500 infantry and a party of cavalry, penetrating as far as

the engineers’ park, cutting down some men, and carrying off several hundred

entrenching tools. The 74th, however, which was the first regiment under arms,

advanced under Major-General Kempt in double quick time, and, with the

assistance of the guard of the trenches, drove back the enemy, who lost 300

officers and men. The work of preparing for the siege and assault went on under

the continuance of very heavy rain, which rendered the work in the trenches

extremely laborious, until the 25th of March, when the batteries opened fire

against the hitherto impregnable fortress; and on that night Fort Picurina was

assaulted and carried by 500 men of the third division, among whom were 200 men

of the 74th under Major Shawe. The fort was very strong, the front well covered

by the glacis, the flanks deep, and the rampart, 14 feet perpendicular from the

bottom of the ditch, was guarded with thick slanting palings above; and from

thence to the top there were 16 feet of an earthen slope. Seven guns were

mounted on the works, the entrance to which by the rear was protected with three

rows of thick paling. The garrison was about 300 strong, and every man had two

muskets. The top of the rampart was garnished with loaded shells to push over,

and a retrenched guardhouse formed a second internal defence. The detachment

advanced about ten o’clock, and immediately alarms were sounded, and a fire

opened from all the ramparts of the work. After a fierce conflict, in which the

English lost many men and officers, and the enemy more than half of the

garrison, the commandant, with 86 men, surrendered. The 74th lost Captain

Collins and Lieutenant Ramadge killed, and Major Shawe dangerously wounded.

The operations of trench-cutting and

opening batteries went on till the 6th of April, on the night of which the

assault was ordered to take place. "The besiegers’ guns being all turned against

the curtain, the bad masonry crumbled rapidly away; in two hours a yawning

breach appeared, and Wellington, in person, having again examined the points of

attack, renewed the order for assault.

"Then the soldiers eagerly made themselves

ready for a combat, so furiously fought, so terribly won, so dreadful in all its

circumstances, that posterity can scarcely be expected to credit the tale, hut

many are still alive who know that it is true."

It was ordered, that on the right the

third division was to file out of the trenches, to cress the Rivillas rivulet,

and to scale the castle walls, which were from 18 to 24 feet high, furnished

with all means of destruction, and so narrow at the top, that the defenders

could easily reach and overturn the ladders.

The assault was to commence at ten

o’clock, and the third division was drawn up close to the Rivillas, ready to

advance, when a lighted carcass, thrown from the castle close to where it was

posted, discovered the array of the men, and obliged them to anticipate the

signal by half an hour. "A sudden blaze of light and the rattling of musketry

indicated the commencement of a most vehement contest at the castle. Then

General Kempt,—for Picton, hurt by a fall in the camp, and expecting no change

in the hour, was not present,—then General Kempt, I say, led the third division.

He had passed the Rivillas in single files by a narrow bridge, under a terrible

musketry, and then reforming, and running up the rugged hill, had reached the

foot of the castle, when he fell severely wounded, and being carried back to the

trenches met Picton, who hastened forward to take the command. Meanwhile his

troops, spreading along the front, reared their heavy ladders, some against the

lofty castle, some against the adjoining front on the left, and with incredible

courage ascended amidst showers of heavy stones, logs of wood, and burning

shells rolled off the parapet; while from the flanks the enemy plied his

musketry with a fearful rapidity, and in front with pikes and bayonets stabbed

the leading assailants, or pushed the ladders from the walls; and all this

attended with deafening shouts, and the crash of breaking ladders, and the

shrieks of crushed soldiers, answering to the sullen stroke of the falling

weights."

The British, somewhat baffled, were

compelled to fall back a few paces, and take shelter under the rugged edges of

the hill. But by the perseverance of Picton and the officers of the division,

fresh men were brought, the division reformed, and the assault renewed amid

dreadful carnage, until at last an entrance was forced by one ladder, when the

resistance slackened, and the remaining ladders were quickly reared, by which

the men ascended, and established themselves on the ramparts.

Lieutenant Alexander Grant of the 74th led

the advance at the escalade, and went with a few men through the gate of the

castle into the town, but was driven back by superior numbers. On his return he

was fired at by a French soldier lurking in the gateway, and mortally wounded in

the back of the head.

He was able, however, to descend the

ladder, and was carried to the bivouac, and trepanned, but died two days

afterwards, and was buried in the heights looking towards the castle. Among the

foremost in the escalade was John M’Lauchlan, the regimental piper, who, the

instant he mounted the castle wall, began playing on his pipes the regimental

quick step, "The Campbells are comin’," as coolly as if on a common parade,

until his music was stopped by a shot through the bag; he was afterwards seen by

an officer of the regiment seated on a gun-carriage, quietly repairing the

damage, while the shot was flying about him. After he had repaired his bag, he

recommenced his stirring tune.

After capturing the castle, the third

division kept possession of it all night, repelling the attempts of the enemy to

force an entrance. About midnight Wellington sent orders to Picton to blow down

the gates, but to remain quiet till morning, when he should sally out with 1000

men to renew the general assault. This, however, was unnecessary, as the capture

of the castle, and the slaughtering escalade of the Bastion St. Vincente by the

fifth division, having turned the retrenchments, there was no further

resistance, and the fourth and light divisions marched into the town by the

breaches. In the morning the gate was opened, and permission given to enter the

town.

Napier says, "5000 men and officers fell

during the siege, and of these, including 700 Portuguese, 3500 had been stricken

in the assault, 60 officers and more than 700 men being slain on the spot. The

five generals, Kempt, Harvey, Bowes, Colville, and Picton were wounded, the

first three severely." At the escalade of the castle alone 600 officers and men

fell. "When the extent of the night’s havoc was made known to Lord Wellington,

the firmness of his nature gave way for a moment, and the pride of conquest

yielded to a passionate burst of grief for the loss of the gallant soldiers."

Wellington in his despatch noticed particularly the distinguished conduct of the

third division, and especially that of lieutenant-Colonels Le Poer Trench and

Manners of the 74th.

The casualties in the regiment during the

siege were:—Killed.—3 officers, Captain Collins, Lieutenants Rainadge and Grant,

1 sergeant, and 22 rank and file. Wounded, 10 officers, Lieut-Colonel the Hon. R

Le Poer Trench, Captain Langlands, Brevet-Major Shawe, Captains Thomson and

Wingate, Lieutenants Lister, Pattison, King, and Ironside, Ensign Atkinson, 7

sergeants, and 91 rank and file.

The 74th left Badajoz on the 11th of

April, and marched to Pincdono, on the frontiers of Beira, where it was encamped

till the beginning of June, when it proceeded to Salamanca. Along with a large

portion of the allied army, the 74th was drawn up in order of battle on the

heights of San Christoval, in front of Salamanca, from the 20th to the 28th of

June, to meet Marshal Marinont, who advanced with 40,000 men to relieve the

forts, which, however, were captured on the 27th. Brevet-Major Thomson of

the 74th was wounded at the siege of the forts, during which he had been

employed as acting engineer.

On the 27th Picton having left on leave of

absence, the command of the third division was entrusted to. Major-General the

Hon. Edward Pakenham.

After the surrender of Salamanca the army

advanced in pursuit of Marmont, who retired across the Douro. Marmont, having

been reinforced, recrossed the Douro, and the allies returned to their former

ground on the heights of San Christoval in front of Salamanca, which they

reached on the 21st of July. In the evening the third division and some

Portuguese cavalry bivouacked on the right bank of the Tormes, over which the

rest of the army had crossed, and was placed in position covering Salamanca,

with the right upon one of the two rocky hills called the Arapiles, and the left

on the Tormes, which position, however, was afterwards changed to one at right

angles with it. On the morning of the 22nd the third division crossed the Tormes,

and was placed in advance of the extreme right of the last-mentioned position of

the allied army. About five o’clock the third division, led by Pakenham,

advanced in four columns, supported by cavalry, to turn the French left, which

had been much extended by the advance of the division of General Thomières, to

cut off the right of the allies from the Cindad Rodrigo road. Thomières was

confounded when first he saw the third division, for he expected to see the

allies in full retreat towards the Cindad Rodrigo road. The British columns

formed line as they marched, and the French gunners sent showers of grape into

the advancing masses, while a crowd of light troops poured in a fire of

musketry.

"But bearing on through the skirmishers

with the might of a giant, Pakenham broke the half formed line into fragments,

and sent the whole in confusion upon the advancing supports." Some squadrons of

light cavalry fell upon the right of the third division, but the 5th Regiment

repulsed them. Pakenham continued his "tempestuous course" for upwards of three

miles, until the French were "pierced, broken, and discomfited." The advance in

line of the 74th attracted particular notice, and was much applauded by Major

General Pakenham, who frequently exclaimed, "Beautifully done, 74th; beautiful,

74th!!’

Lord Londonderry says, in his Story of the Peninsular

War:—

"The attack of the third division was not only the most

spirited, but the most perfect thing of the kind that modern times have

witnessed.

"Regardless alike of a charge of cavalry

and of the murderous fire which the enemy’s batteries opened, on went these

fearless warriors, horse and foot, without check or pause, until they won the

ridge, and then the infantry giving their volley, and the cavalry falling on,

sword in hand, the French were pierced, broken, and discomfited. So close indeed

was the struggle, that in several instances the British colours were seen waving

over the heads of the enemy’s battalions."

Of the division of Thomières, originally

7000 strong, 2000 had been taken prisoners, with two eagles and eleven pieces of

cannon. The French right resisted till dark, when they were finally driven from

the field, and having sustained a heavy loss, retreated through the woods across

the Tormes.

The casualties in the regiment at the

battle of Salamanca were :—Killed, 3 rank and file. Wounded, 2 officers,

Brevet-Major Thomson and Lieutenant Ewing, both severely; 2 sergeants,

and 42 rank and file.

Alter this the 74th, with the other allied

regiments, proceeded to Madrid, where it remained till October 20, the men

passing their time most agreeably. But, although there was plenty of gaiety,

Madrid exhibited a sad combination of luxury and desolation; there was no money,

the people were starving, and even noble families secretly sought charity.

In the end of September, when the distress

was very great, Lieutenant-Colonel Trench and the officers of the 74th and 45th

Regiments, having witnessed the distress, and feeling the utmost compassion for

numbers of miserable objects, commenced giving a daily dinner to about 200 of

them, among whom were some persons of high distinction, who without this

resource must have perished. Napier says on this subject, that "the Madrilenos

discovered a deep and unaffected gratitude for kindness received at the hands of

the British officers, who contributed, not much, for they had it not, but enough

of money to form soup charities, by which hundreds were succoured. Surely this

is not the least of the many honourable distinctions those bravo men have

earned."

During the latter part of October and the

month of November, the 74th, which had joined Lieutenant-General Hill, in order

to check the movement of Souls and King Joseph, performed many fatiguing marches

and counter marches, enduring many great hardships and privations, marching over

impassable roads and marshy plains, under a continued deluge of rain, provisions

deficient, and no shelter procurable. On the 14th of November the allied army

commenced its retreat from Alba de Tormes towards Ciudad Rodrigo, and the

following extract from the graphic journal of Major Alves of the 74th will give

the reader some idea of the hardships which these poor soldiers had to undergo

at this time:—" From the time we left the Arapeiles, on the 15th, until our

arrival at Ciudad Rodrigo, a distance of only about 15 leagues, we were under

arms every morning an hour before daylight, and never got to our barrack until

about sunset, the roads being almost unpassable, particularly for artillery, and

with us generally ankle deep. It scarcely ceased to rain during the retreat. Our

first endeavour after our arrival at out watery bivouack, was to make it as

comfortable as circumstances would admit; and as exertion was our best

assistance, we immediately set to and cut down as many trees as would make a

good fire, and then as many as would keep us from the wet underneath. If we

succeeded in making a good enough fire to keep the feet warm, I generally

managed to have a tolerably good sleep, although during the period I had

scarcely ever a dry shirt. To add to our misery, during the retreat we were

deficient in provisions, and had rum only on two days. The loss of men by death

from the wet and cold during this period was very great. Our regiment alone was

deficient about thirty out of thirty-four who had only joined us from England on

the 14th, the evening before we retreated from the Arapiles."

The 74th went into winter quarters, and

was cantoned at Sarzedas, in the province of Beira, from December 6, 1812, till

May 15, 1813.

During this time many preparations were

made, and the comfort and convenience of the soldiers maintained, preparatory to

Wellington’s great attempt to expel the French from the Peninsula.

The army crossed the Douro in separate

divisions, and reunited at Toro, the 74th proceeding with the left column.

Lieutenant-General Picton had rejoined from England on the 20th May.

On the 4th of June the allies advanced,

following the French army under King Joseph, who entered upon the position at

Vittoria on the 19th of June by the narrow mountain defile of Puebla, through

which the river Zadorra, after passing the city of Vittoria, runs through the

valley towards the Ebro with many windings, and divides the

basin unequally. To give

an idea of the part taken by the 74th in the important battle of Vittoria, we

cannot do better than quote from a letter of Sir Thomas Picton dated July 1,

1813.

"On the 16th of May the division was put

in movement; on the 18th we crossed the Douro, on the 15th of June the Ebro, and

on the 21st fought the battle of Vittoria. The third division had, as usual, a

very distinguished share in this decisive action. The enemy’s left rested on an

elevated chain of craggy mountains, and their right on a rapid river, with

commanding heights in the centre, and a succession of undulating grounds, which

afforded excellent situations for artillery, and several good positions in front

of Vittoria, where King Joseph had his headquarters. The battle began early in

the morning, between our right and the enemy’s left, on the high craggy heights,

and continued with various success for several hours. About twelve o’clock the

third division was ordered to force the passage of the river and carry the

heights in the centre, which service was executed with so much rapidity, that we

got possession of the commanding ground before the enemy were aware of our

intention. The enemy attempted to dislodge us with great superiority of force,

and with forty or fifty pieces of cannon. At that period the troops on our right

had not made sufficient progress to cover our right flank, in consequence of

which we suffered a momentary check, and were driven out of a village whence we

had dislodged the enemy, but it was quickly recovered; and on Sir Rowland Hill’s

(the second) division, with a Portuguese and Spanish division, forcing the enemy

to abandon the heights, and advancing to protect our flanks, we pushed the enemy

rapidly from all his positions, forced him to abandon his cannon, and drove his

cavalry and infantry in confusion beyond the city of Vittoria. We took 152

pieces of cannon, the military chest, ammunition and baggage, besides an immense

treasure, the property of the French generals amassed in Spain.

"The third division was the most severely

and permanently engaged of any part of the army; and we in consequence sustained

a loss of nearly 1800 killed and wounded, which is more than a third of the

total loss of the whole army."

The 74th received particular praise from

both Lieutenant-General Picton and Major-General Brisbane, commanding the

division and brigade, for its alacrity in advancing and charging through the

village of Arinez.

The attack on and advance from Arinez

seems to have been a very brilliant episode indeed, and the one in which the

74th was most particularly engaged. The right wing, under Captain M’Queen, went

off at double quick and drove the enemy outside the village, where they again

formed in line opposite their pursuers. The French, however, soon after fled,

leaving behind them a battery of seven guns.

Captain M’Queen’s

own account of the battle

is exceedingly graphic. "At Vittoria," he says, "I had the command of three

companies for the purpose of driving the French out of the village of Arinez,

where they were strongly posted; we charged through the village and the enemy

retired in great confusion. Lieutenants Alves and Ewing commanded the companies

which accompanied me. I received three wounds that day, but remained with the

regiment during the whole action; and next day I was sent to the rear with the

other wounded. Davis (Lieutenant) carried the colours that day, and it was one

of the finest things you can conceive to see the 74th advancing in line, with

the enemy in front, on very broken ground full, of ravines, as regularly, and in

as good line as if on parade. This is in a great measure to be attributed to

Davis, whose coolness and gallantry were conspicuous; whenever we got into

broken ground, he with the colours was first on the bank, and stood there until

the regiment formed on his right and left."

Captain M’Queen, who became Major of the

74th in 1830, and who died only a year or two ago, was rather a remarkable man;

we shall refer to him again. Adjutant Alves tells us in his journal, that in

this advance upon the village of Arinez, he came upon Captain M’Queen lying, as

he thought, mortally wounded. Alves ordered two of the grenadiers to lift

M’Queen and lay him behind a bank out of reach of the firing, and there leave

him. About an hour afterwards, however, Alves was very much astonished to see

the indomitable Captain at the head of his company; the shot that had struck him

in the breast having probably been a spent one, which did not do him much

injury.

Major White (then Adjutant) thus narrates

an occurrence which took place during the contest at Arinez:— "At the battle of

Vittoria, after we had forced the enemy’s centre, and taken the strong heights,

we found ourselves in front of a village (I think Arinez) whence the French had

been driven in a confused mass, too numerous for our line to advance against;

and whilst we were halted for reinforcements, the 88th Regiment on our left

advanced with their usual impetuosity against the superior numbers I have spoken

of, and met with a repulse. The left of our regiment, seeing this, ran from the

ranks to the assistance of the 88th; and I, seeing them fall uselessly, rode

from some houses which sheltered us to rally them and bring them back. The piper

(M’Laughlan, mentioned before) seeing that I could not collect them, came to my

horse’s side and played the ‘Assembly,’ on which most of them that were not shot

collected round me. I was so pleased with this act of the piper in coming into

danger to save the lives of his comrades, and with the good effect of the pipes

in the moment of danger that I told M’Laughlan that I would not fail to mention

his gallant and useful conduct. But at the same time, as I turned my horse to

the right to conduct the men towards our regiment, a musket ball entered the

point of my left shoulder, to near my back bone, which stopped my career in the

field. The piper ceased to play, and I was told he was shot through the breast;

at all events he was killed, and his timely assistance and the utility of the

pipes deserves to be recorded." It was indeed too true about poor brave

M’Laughlan, whose pipes were more potent than the Adjutant’s command; a

nine-pound shot went right through his breast, when, according to the journal of

Major Alves, he was playing "The Campbell’s are comin" in rear of the column. It

is a curious circumstance, however that the piper’s body lay on the field for

several days after the battle without being stripped of anything but the shoes.

This was very unusual, as men were generally stripped of everything as soon as

they were dead.

When the village was captured and the

great road gained, the French troops on the extreme left were thereby turned,

and being hardly pressed by Sir Rowland Hill’s attack on their front, retreated

in confusion before the advancing lines towards Vittoria.

The road to Bayonne being completely

blocked up by thousands of carriages and animals, and a confused mass of men,

women, and children, thereby rendered impassable for artillery, the French

retreated by the road to Salvatierra and Pamplona, the British infantry

following in pursuit. But this road being also choked up with carriages and

fugitives, all became confusion and disorder. The French were compelled to

abandon everything, officers and men taking with them only the clothes they

wore, and most of them being barefooted. Their loss in men did not, however,

exceed 6000, and that of the allies was nearly as great. That of the British,

however, was more than twice as great as that of the Spanish and Portuguese

together, and yet both are said to have fought well; but as Napier says,

"British troops are the soldiers of battle."

The French regiments which effected their

escape arrived at Pamplona and took shelter in the defile beyond it, in a state

of complete disorganisation. Darkness, and the nature of the ground unfavourable

for the action of cavalry, alone permitted their escape; at the distance of two

leagues from Vittoria the pursuit was given up.

The following, Brigade Order was issued the day after the

battle:—

"Major-General Brisbane has reason to be highly pleased

with the conduct of the brigade in the action of yesterday, but he is at a loss

to express his admiration of the conduct of the Honourable Colonel Le Poer

Trench and the 14th Regiment, which he considers contributed much to the success

of the day."

The casualties in the 74th at the battle

of Vittoria were: —Killed, 7 rank and file; wounded, 5 officers, Captains

M’Queen and Ovens, Adjutant White, and Ensigns Hamilton and Shore, 4 sergeants,

1 drummer, and 31 rank and file.

The army followed the retreating French

into the Pyrenees by the valley of Roncesvalles.

Of the various actions that took place

among these mountains we have already given somewhat detailed accounts when

speaking of the 42nd. The 74th was engaged in the blockade of Pamplona, and

while thus employed, on the 15th of July, its pickets drove in a reconnoitring

party of the garrison, the regiment sustaining a loss of 3 rank and file killed,

and 1 sergeant and 6 rank and file wounded. On the 17th the blockade of Pamplona

was entrusted to the Spaniards, and the third, fourth, and second divisions

covered the blockade, as well as the siege of San Sebastian, then going on under

Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Graham.

Marshal Soult, with 60,000 men, advanced

on the 25th to force the pass of Roncesvalles, and compelled the fourth

division, which had been moved up to support the front line of the allies, to

retire; on the 26th it was joined by the third division in advance of Zubiri.

Both divisions, under Sir Thomas Picton, took up a position on the morning of

the 27th July, in front of Pamplona, across the mouth of the Zubiri and Lanz

valleys. At daylight on the 30th, in accordance with Wellington’s orders, the

third division, with two squadrons of cavalry and a battery of artillery,

advanced rapidly up the valley of the Zubiri, skirmishing on the flank of the

French who were retiring under General Foy. About eleven o’clock, the 74th being

in the valley, and the enemy moving in retreat parallel with the allies along

the mountain ridge to the left of the British, Lieut-Colonel Trench obtained

permission from Sir Thomas Picton to advance with the 74th and cut off their

retreat The regiment then ascended the ridge in view of the remainder of the

division, which continued its advance up the valley. On approaching the summit,

two companies, which were extended as skirmishers, were overpowered in passing

through a wood, and driven back upon the main body. Though the regiment was

exposed to a most destructive fire, it continued its advance, without returning

a shot, until it reached the upper skirt of the wood, close upon the flank of

the enemy, and then at once opened its whole fire upon them.

A column of 1500 or 1600 men was separated

from the main body, driven down the other side of the ridge, and a number taken

prisoners; most of those who escaped were intercepted by the sixth division,

which was further in advance on another line. After the 74th had gained the

ridge, another regiment from the third division was sent to support it, and

pursued the remainder of the column until it had surrendered to the sixth

division. Sir Frederick Stoven, Adjutant-General of the third division, who,

along with some of the staff cams up at this moment, said he never saw a

regiment behave in such a gallant manner.

The regiment was highly complimented by

the staff of the division for its conspicuous gallantry on this occasion, which

was noticed as follows by Lord Wellington, who said in his despatch,— "I cannot

sufficiently applaud the conduct of all the general officers, officers, and

troops, throughout these operations, &c.

"The movement made by Sir Thomas Picton

merited my highest commendation; the latter officer co-operated in the attack of

the mountain by detaching troops to his left, in which Lieutenant-Colonel the

Hon. Robert Trench was wounded, but I hope not seriously."

The regiment on this occasion sustained a

loss of 1 officer, Captain Whitting, 1 sergeant, and 4 rank and file killed, and

5 officers, Lieut.-Colonel the Hon. Robert Le Poer Trench, Captain

(Brevet-Major) Moore, and Lieutenants Pattison, Duncomb, and Tew, 4 sergeants,

and 36 rank and file wounded.

The French were finally driven across the

Bidasoa into France in the beginning of August.

At the successful assault of the fortress

of San Sebastian by the force under Sir Thomas Graham, and which was witnessed

by the 74th from the summit of one of the neighbouring mountains, Brevet Major

Thomson of the 74th, was employed as an acting engineer, and received the brevet

rank of Lieutenant-Colonel for his services.

Alter various movements the third division

advanced up the pass of Zagaramurdi, and on the 6th October encamped on the

summit of a mountain in front of the pass of Echalar; and in the middle of that

month, Sir Thomas Picton having gone to England, the command of the third

division devolved upon Major-General Sir Charles Colville. The 74th remained

encamped on the summit of this bare mountain till the 9th of November, suffering

greatly from the exposure to cold and wet weather, want of shelter, and scarcity

of provisions, as well as from the harassing piquet and night duties which the

men had to perform. Major Alves [This officer was present with the 74th during

the whole of its service in the Peninsula, and kept an accurate daily journal of

all the events in which he was concerned. He was afterwards

Major of the depot

battalion in the Isle of Wight.] says in his journal that the French picquets

opposite to the position of the 74th were very kind and generous in getting the

soldiers’ canteens filled with brandy,—for payment of course.

Pamplona having capitulated on the 31st of

October, an attack was made upon the French position at the Nivelle on the 10th

of November, a detailed description of which has been given in the history of

the 42nd. The third, along with the fourth and seventh divisions, under the

command of Marshal Beresford, were dispersed about Zagaramurdi, the Puerto de

Echellar, and the lower parts of these slopes of the greater Rhune, which

descended upon the Sarre. On the morning of the 10th, the third division, under

General Colville, descending from Zagaramurdi, moved against the unfinished

redoubts and entrenchments covering the approaches to the bridge of Amotz on the

left bank of the Nivelle, and formed in conjunction with the sixth division the

narrow end of a wedge. The French made a vigorous resistance, but were driven

from the bridge, by the third division, which established itself on the heights

between that structure and the unfinished redoubts of Louis XIV. The third

division then attacked the left flank of the French centre, while the fourth and

seventh divisions assailed them in front. The attacks on other parts of the

French position having been successful, their centre was driven across the river

in great confusion, pursued by the skirmishers of the third division, which

crossed by the bridge of Amotz. The allied troops then took possession of the

heights on the right bank of the Nivelle, and the French were compelled to

abandon all the works which for the previous three months they had been

constructing for the defence of the other parts of the position.

The 74th was authorised to bear the word "Nivelle"

on its regimental colour, in commemoration of its services in this battle;

indeed it will be seen that it bears on its colours the names of nearly every

engagement that took place during the Peninsular War. The French had lost 51

pieces of artillery, and about 4300 men and officers killed, wounded, and

prisoners, during the battle of the Niveile; the loss of the allies was about

2700 men and officers.

On the 9th of December the passage of the

Nive at Cambo having been forced by Sir Rowland Hill, the third division

remained in possession of the bridge at Ustariz. On the 13th the French having

attacked the right between the Nive and the Adour at, St Pierre, were repulsed

by Sir Rowland Hill after a very severe battle, and the fourth, sixth, and two

brigades of the third division were moved across the Nive in support of the

right.

The 74th, after this, remained cantoned in

farm-houses between the Nive and the Adour until the middle of February 1814.

Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Picton

having rejoined the army, resumed the command of the third division in the end

of December 1813. Many acts of outrage and plunder had been committed by the

troops, on first entering France, and Sir Thomas Picton took an opportunity of

publicly reprimanding some of the regiments of his division for such offences,

when he thus addressed the 74th:—"As for you, 74th, I have nothing to say

against you, your conduct is gallant in the field and orderly in quarters! And,

addressing Colonel Trench in front of the regiment, he told him that he would

write to the colonel at home (General Sir Alexander Hope) his report of their

good conduct. As Lieutenant-General Picton was not habitually lavish of

complimentary language, this public expression of the good opinion of so

competent a judge was much valued by the regiment.

The next engagement in which the 74th took

part was that of Orthes, February 27, 1814. On the 24th the French had