1. County and Shire. Name and Administration of Shetland

Shetland or Zetland is derived from the Norse Hjaltland, variant spellings being Hieltland, Hietland, Hetland. The Norse word is of doubtful origin.

Like Orkney, Shetland cannot be regarded as strictly a Scottish county till the seventeenth century. During that century various County Acts were framed for the better government of the islands. These lasted till 1747, when heritable jurisdiction was abolished and the judicial administration of Shetland was assimilated to the general Scottish system.

Shetland has the same Lord-Lieutenant as Orkney, but separate Deputy Lieutenants and Justices of the Peace. It shares a Sheriff-Principal with Orkney and Caithness, but has a Sheriff-Substitute of its own. The County Council, the Education Authority, Parish Councils, and Town Council of Lerwick are the administrative bodies. The civil parishes are: Unst, Fetlar, Yell, Northmavine, Delting, Walls, Sandsting, Nesting, Tingwall, Lerwick, Bressay, Dunrossness.

In Parliament one member represents both Orkney and Shetland.

Ecclesiastically the parishes are divided into three presbyteries, Lerwick, Burravoe and Olnafirth, which make up the Synod of Shetland.

2. General Characteristics

The county of Shetland is entirely insular, and its characteristics are varied. The coast-line is generally broken and rugged, and in many places precipitous; while the larger islands are intersected by numerous

bays and voes stretching far inland, which form safe and commodious places of anchorage and easy means of communication. No point in Shetland is more than three miles from the sea. Detached rocks and stacks, some high above the water and others below the surface, present a forbidding aspect to the spectator, and increase the dangers of navigation round the coast.

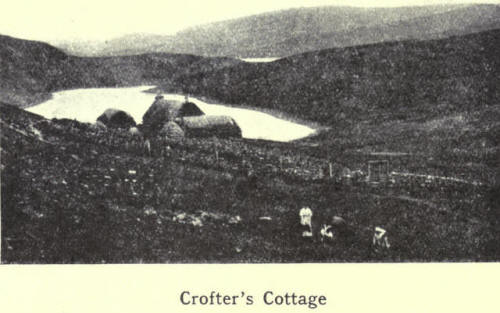

To be near the sea—their chief source of food—the early settlers made their homes close to the shore, where also they generally found the soil better than further inland. Accordingly most of the houses and crofts are situated along the coast, and in particular at the heads of voes, where often townships and villages have been formed. One striking feature is the bold contrast between the green cultivated township and the dark background of moor or hill, sharply marked off from each other by the ancient "toon" dykes. Still more noticeable are the large tracts of permanent pasture, where one may still see the ruins of cottages, once the homes of crofters who were evicted to make room for sheep.

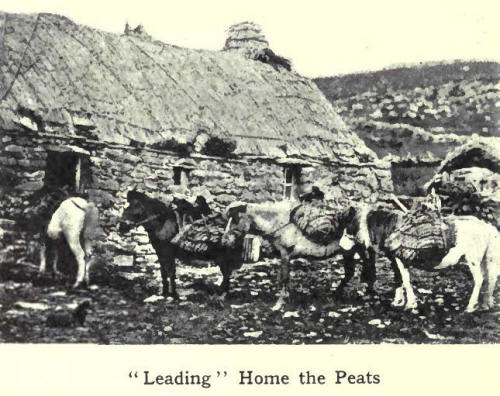

The principal fuel in the islands is peat, the cutting of which, carried on for centuries, ever since the time of Torf Einar, who is said to have taught the natives the use of "turf" for burning, has denuded the surface, and left it blacker than it otherwise would be. That, and the practice of "scalping" turf for roofing purposes, have laid bare great stretches of what might have been fairly good pasture ground.

The proportion of arable land is very small compared with the whole land surface of the islands. For this reason Shetland has never figured as an agricultural county; and other causes may be mentioned, such as divided attention between the two branches of industry. —fishing and crofting; indifferent soil; variable climate; antiquated methods of cultivation; and want of markets for agricultural produce.

Being far removed from the centres of commerce, and having few natural resources in themselves, the islands are almost entirely lacking in manufactures. Fishing and farming are the chief industrial pursuits, while the rearing of native sheep, ponies and cattle form a considerable part of the rural economy. Along with every croft or holding goes the right of common pasturage in the hills and moors, called "scattald." Crofts would be of little value without this common grazing, which is a remnant of the old Norse odal system of land tenure, and is peculiar to the islands of Shetland and Orkney. The word scaltald is from scat, a payment, akin to scot in "scot and lot."

3. Size. Position. Boundaries

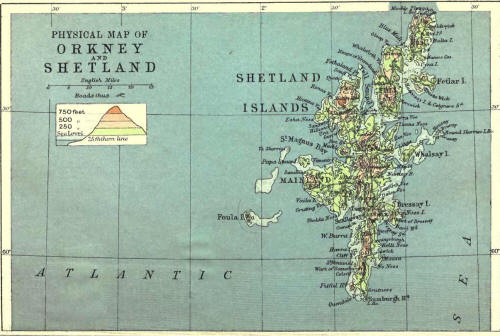

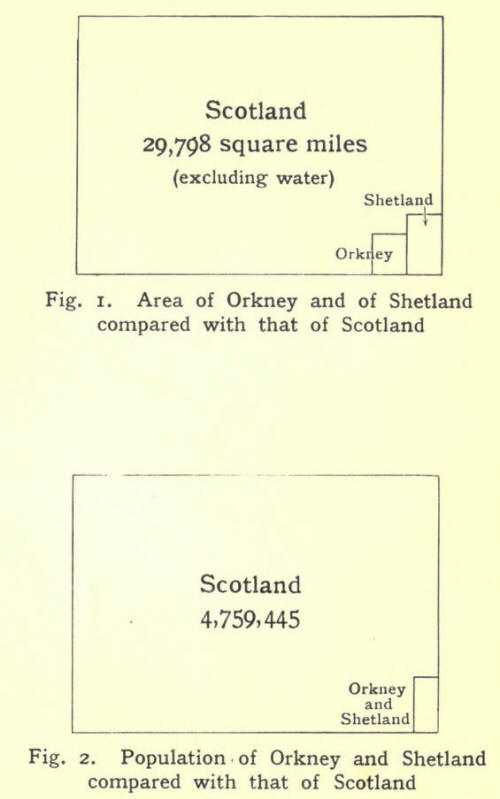

In size, Shetland ranks fifteenth among the Scottish counties; but in population only twenty-seventh. The total area (excluding water) is 352,319 acres or 55021 square miles. The group consists of about one hundred islands, of which twenty-nine are inhabited. The largest is Mainland, which embraces about three-fourths of the whole land-surface; and the others, in point of size, are Yell, Unst, Fetlar, Bressay and Whalsay. Yell measures 17½ miles by 6½, Unst 12 by nearly 6. The smaller islands include East and Vest Burra, Muckle Roe, Papa Stour, Skerries, Fair Isle and Foula; the remainder consisting of islets, holms, stacks and skerries. From Fair Isle, which lies about mid-way between Orkney and Shetland, to Sumburgh Head, is 20¼ miles; and from that point to Flugga in Unst, in a straight line, is 71 miles. From Sumburgh Head to Fethaland, the most northerly part of the Mainland, is 54 miles; and the greatest breadth, from the Mull of Eswick to Muness, is about 21 miles.

Including Fair Isle and Foula, the group lies between the parallels of 59° 30' and 60° 52' north latitude; and between 0° 43' and 2° 7' west longitude. The general trend of the islands is north-easterly, and their position in relation to the mainland of Scotland is also in that direction; Sumburgh Head being 95 miles north-east of Caithness and 164 miles north of Aberdeen.

The North Sea washes the eastern sea-board, and the Atlantic Ocean the western; sea and ocean join forces between Sumburgh Head and Fair Isle to form that turbulent tideway called the "Roost." They also meet north of Yell and Unst, where the Atlantic sets strongly through Yell Sound and Blue Mull Sound for six hours during flood tide, and the North Sea, in its turn, in the opposite direction for other six hours.

4. Surface and General Features

The surface of the larger islands is hilly, and the general direction of the ridges is north and south, corresponding to the length of the islands. The inland parts present an undulating surface of peat bogs and moorland, dotted here and there with fresh-water lochs, which accentuate, rather than relieve, the monotony of the landscape. The hills are round or conical in shape and of moderate height, ranging from 500 to 900 feet. Unlike the rounded hills of the Lowlands of Scotland, which are often grassy to the top, most of the Shetland hills are brown and barren, being covered with heather and moss or short coarse grass. Neither have they the rugged grandeur of the Highlands, for the sides are generally smooth and rounded, the result of intense glaciation.

The highest in the Mainland is Ronas Hill, Northmavine, a great mass of red granite, rising to a height of 1475 feet, forming the culminating point of the North Roe tableland, and having the hilly ridge of the Bjorgs on its eastern side. A long range of hills extends through the parish of Delting, from Firth Ness to Olnafirth; and from the south side of that inlet it extends southward to Russa Ness on the west side of Weisdale Voe. This is the loftiest range, and the southern ridge forms a complete barrier between the east and west side of that part of the Mainland. The highest hill in this chain is Scallafield, 921 feet. Other two parallel ridges lie east of this, the one from the east side of Weisdale Voe to Dales Voe in Delting; and the other from near Scalloway in a north-east direction to Collafirth. There are breaks in these hilly ridges, notably where the county road crosses over near Sandwater, and again between Olnafirth on the west and Dury Voe on the east. The other range worthy of note extends from the Wart of Scousburgh in Dunrossness, with intervening breaks, to the east of Scalloway, where it divides into two ridges, and stretches onward to the east and west sides of hales Voe. Fitful Head in the south, 928 feet; Sandness Hill in the west, 817 feet; the Sneug in Foula, 1372 feet; the Wart of Bressay, 742 feet; and the Noup of Noss, 592 feet, are conspicuous land-marks round the coast. The island of Yell is hilly, with parallel ridges running north-east and south-west—highest point, the Ward of Otterswick. A range of hills extends along the west side of Unst— highest point, Vallafield, 708 feet. In the extreme north is Hermaness, 657 feet; while on the opposite side of Burrafirth is the still higher hill of Saxa Vord, 934 feet.

In the larger islands the land is generally lower on the east side than on the west; and in many cases the hills are steeper on the west than on the east. Most of the smaller islands are low-lying and grassy, forming excellent pasture ground for sheep.

There are many fresh-water lochs in the islands, the largest being Girlsta Loch in Tingwall, Loch of Cliff in Unst, and Spiggie in Dunrossness. They are nearly all well stocked vith trout, which makes Shetland attractive to anglers. Shetland has no streams large enough to be called rivers ; but it has burns in plenty, rippling brooks in summer and brawling torrents of brown peaty water in winter, when the soil is sodden with rain or snow.

5. Geology and Soil

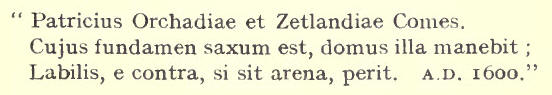

The geological snap shows that metamorphic rocks cover the greater part of Shetland. These rocks are represented by the clayslates and schists that extend from Fitful Head to the Mull of Eswick ; and by the gneiss found from Scalloway to Delting, and also on Burra Isle and Trondra, `Vhalsay and Skerries, Yell, the west side of Unst and of Fetlar, the east side of Northmavine, and the north sea-board of the SandnessAithsting peninsula. Associated with the two series of metamorphic rock are bands of quartzite; while at Fladdabister, Tingwall, Whiteness, Weisdale, Northmavine and Unst are beds of limestone.

The geological formation of Unst is interesting. The gneiss on the west is succeeded by a band of mica, chlorite and graphite schists. Next come zones of serpentine and gabbro, to be followed by schistose rocks at Muness. Fetlar shows a similar formation.

Of the igneous rocks we may mention first the intrusive granites of Northmavine, Muckle Roe, Vementry, Papa Stour, Melby and South Sandsting. A bed of diorite extends from Ronas Voe to Olnafirth. Part of Muckle Roe also shows diorite. Syenite occurs round Loch Spiggie and is traced northward through Oxna and Hildasay to Bixter and Aith. Lava, tuff, and other volcanic materials appear in various parts of the islands, as between Stennis and Ockran Head, in Northmavine, Papa Stour, the Holm of Melby, Vementry and Bressay.

The predominating sedimentary rocks in Shetland belong to the Old Red Sandstone formation. These are found from Sumburgh Head to Rova Head, and in Fair Isle, Mousa and Bressay. The fault or boundary line between them and the metamorphic rocks is clearly traceable at various points along the east of the Mainland. Foula, Sandness and Papa Stour, on the west, show remnants of Old Red Sandstone. This formation is believed to have once covered the whole area now represented by the Shetlands. To the same geological period the hardened sandstone is considered to belong, which occurs in the western peninsula, covering most of the district of Sandness, Walls, Sandsting and Aithsting.

Glacial phenomena—striae, moraines, boulders—are interesting features in the geology of Shetland. Over Unst, Fetlar, Yell and the north of Mainland the movement of the ice had been uniformly from east to west. Over the middle and southern districts, the glaciers had curved in a north-westerly direction.

The variety of rocks accounts for the variety of soils in the islands. There are many fertile regions of sandy and loamy soil. Perhaps the best is the limestone district of Tingwall. Most of the county, however, is covered with peat moss and peaty soil.

6. Natural History

The mammals of Shetland are comparatively few. There are no deer, foxes or badgers. Rats and mice are numerous, hedgehogs are fairly common. Moles and bats are unknown. So, too, are snakes, lizards, frogs and toads. The weasel is found in many districts, and its near relative, the ferret, is used for hunting rabbits, which are plentiful everywhere. Hares were imported some time ago, but have a hard struggle for existence with so many enemies around. Along the shore may occasionally be seen the sea-otter, when he comes up on a rock to enjoy a feast of sea-trout, or to

venture inland in search of fresh water. lie must needs be wary, as he is greatly sought after for the sake of his valuable skin. Another amphibian is the seal, whose habitat is the base of inaccessible cliffs and out-lying rocks and isles.

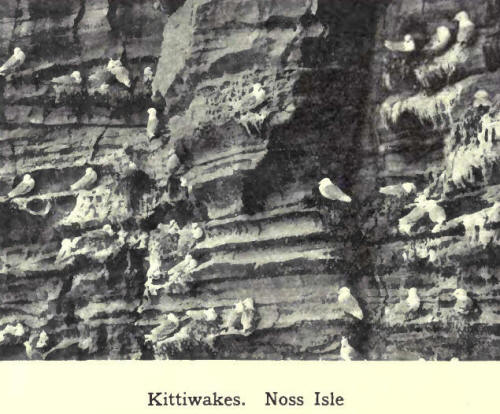

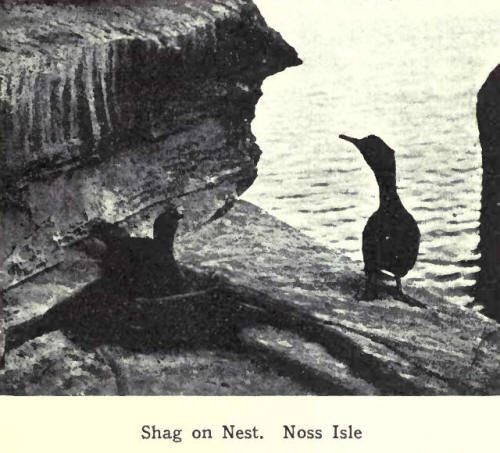

The birds of Shetland may be divided into residents, summer visitors, and winter visitors. In the great annual migrations which take place in spring and again in autumn, the islands form a resting-place for the feathered voyagers, some of whom stay to nest. Sea fowl naturally predominate. The gull family is the

most numerous and includes the great black-backed gull, the lesser black-hack, the herring gull, the common gull, the black-headed gull and the pretty kittiwake. Shags (scarfs) and cormorants are abundant all the year round; and in their season come the guillemots, razorbills, puffins, manx shearwaters and little auks. The guillemots congregate in thousands on the rocky ledges of cliff, where each female lays a solitary egg. on the bare rock. The egg is so formed that, even if disturbed, it will not roll off the shelf on which it lies. The plumage of the black guillemot or "tystie" during the winter season is of a mottled-grey colour, and the bird is difficult to recognise in its changed appearance. Eider ducks are abundant, and the great northern diver (emmer goose) may often be seen.

Colonies of fulmar petrels are spreading all round the coast, while the stormy petrel comes to nest in the outer islands. The piratical skua is common; and the great skua, which is strictly protected, is on the increase in certain localities. Among the shore birds may he mentioned the noisy terns and oyster-catchers. In the winter come the turnstones, sandpipers, dunlins and redshanks. Among the divers may be noted the golden-eye, merganser, and long-tailed duck, while the stock-duck, teal and widgeon are fairly plentiful.

Wild geese and swans, anti flocks of rooks occasionally rest on their journey, but the rooks, though numerous elsewhere in Britain, do not take up residence in Shetland longer than they can help. Ravens and hooded-crows are plentiful. The peregrine falcon, the merlin, the kestrel and the lordly sea-eagle are among the birds of prey. Of game birds, the ringed plover, curlew, snipe, golden plover and rock pigeons are common, while woodcock make their appearance during the migratory flight in autumn.

Starlings, sparrows and linnets are plentiful ; and owing to the almost entire absence of other songsters, the song of the skylark is more noticeable. Among summer visitors may he mentioned the wheat-ear, land-rail and peewit, while swallows and martins may be seen occasionally. Winter visitors include field-fares, buntings, redwings, robin redbreasts, blackbirds, thrushes and the smallest of all British birds, the golden-crested wren. The tiny wren, misnamed the " robin," with its cheery song and hide-and-seek ways among the rocks, stays all the year round, as do also the rock and meadow pipits.

Absence of trees and hedgerows, and the general bareness of the ground, bring into prominence the different varieties of wild flowers. On the moors and hillsides grow the crisp heather and heath, with occasional patches of crowberry, while peeping out among these are the milk-wort, the butter-wort and bog asphodel, with the downy cotton-grass in damp places. The pretty yellow tormentil is everywhere among the stunted grass. The spotted orchis, the yellow buttercup and the lovely grass of Parnassus are also conspicuous on the grassy uplands. In meadow lands and marshy places are found the purple orchis, marsh-marigold, marsh cinquefoil, lady's smock, ragged robin, and red and yellow rattle, while in ditches may be seen different varieties of the crow-foot tribe and scorpion grass (forget-me-nots). On dry banks may be found the scented thyme, white and yellow bed-straws, and near by, the bird's foot trefoil. Daisies, scentless Mayweed and eyebrights are everywhere. In some corn-lands the red poppy shines forth; while the wild mustard and radish (runchie) are only too common. Growing in the cliffs are rose-root, scurvy grass and sea-campions (misnamed sweet-William). The vernal squill, hawk-weed and sheep's scabious spangle the green pasture, and sea-pinks are all round the shore, extending in some places to the water's edge. The mountain-ash, the wild rose and the honeysuckle grow in sheltered nooks.

7. Round the Coast--(a) Along the East from Fair Isle to Unst

The extent of coast-line is enormous, and only the outstanding features can be noted here.

Fair Isle, rock-bound, precipitous and lonely, with but one or two small creeks where vessels may shelter, has two lighthouses, each with a fog-siren and a group-flashing white light--the Scaddon, visible 16 miles, and the Scroo, visible 23 miles. It was on Fair Isle that El Gran Grifon, one of the Armada ships, was wrecked in 188.

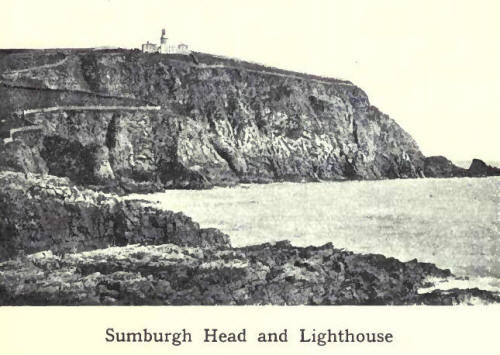

Sumburgh Head, the most southerly point of the Mainland, is also capped with a lighthouse, perched 300 feet above the swirling eddies of the Roost. Erected in 1820, it was the first lighthouse on the Shetland coast. Its group-flashing white light is visible 24 miles in clear weather. North of Sumburgh Head are Grutness Toe and the Pool of Virkie, with their low-lying sandy shores while near by are Sumburgh House and the ruins of Jarlshoff. From this point northward the coast is rocky, with moderately low cliffs, which are broken up by the inlets of Voe and Troswick. The next conspicuous point is the headland of Noness, crowned by a small, quick-flashing white light, a guide to the busy fishing centre of Sandwick, and the fine sandy bay of

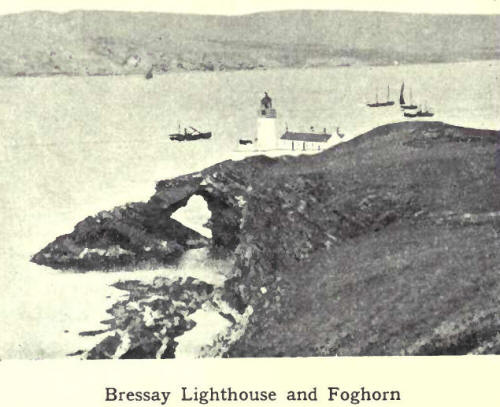

Levenwick, which lies directly ol>l>osite. Passing through Mousa Sound, we have on the right the low-lying grazing island of Mousa with its famous Pictish castle, and on the left Sandlodge, near which are disused copper-mines. Two miles north of Mousa is the low-lying point of Helliness, having at its base the small harbour of Aithsvoe. From here onwards the coast is of varying heights, and broken by the exposed creeks of Fladdabister, Quarff, Gulberwick, Sound and Brei \Vick. Bressay lighthouse, which has a revolving red and white light, visible z6 miles, shows the way to Bressay Sound and the harbour of Lerwick.

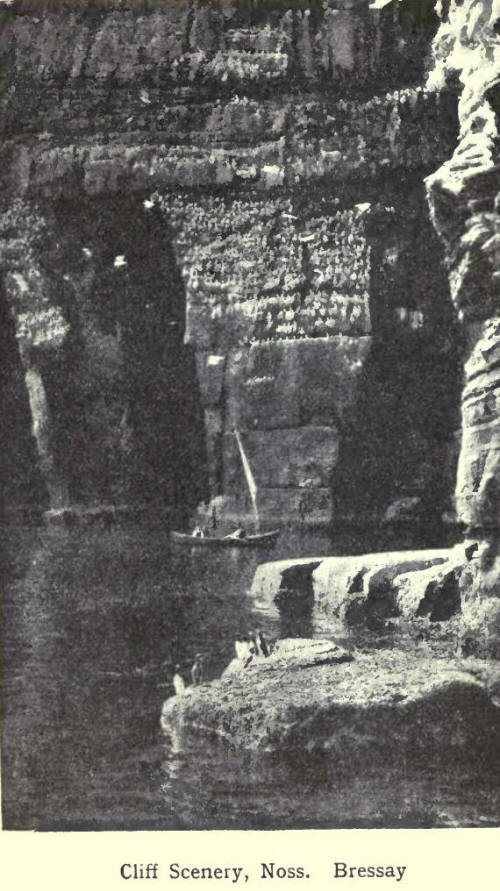

The shores of Bressay are low-lying on the west and north ; but on the south are the high cliffs of the Ord and Bard, the latter having the Orkneyman's Cave and the mural arch of the Giant's Leg at its base. On the east side of Noss Isle the cliffs are also high, forming the favourite breeding-ground of myriads of sea-birds. The diversity of the coast-line, with the sudden transition

from an uninteresting shore to bold, precipitous cliffs, is owing to the dip of the rock-strata. If the dip is to the sea, there is a more or less gradual slope to the shore ; but if the dip is from the sea, then there is the towering cliff, facing the waves like a giant wall. A good example of this is in the island of Noss, which is 592 feet high at the Noup, and gradually slopes down to near sea-level at the western side. The general outline of the cliffs, too, depends on the texture of the rocks. With sandstone, they tower up in regular layers like a wall, bold and massive, with clear-cut caves and tall stacks. With schistose and granite rocks, however, the cliffs are more broken and rugged.

Proceeding from the north entrance of Lerwick harbour, we find a light on Rova Head, with red, white and green sectors, guiding the mariner to and from this narrow channel. The sea is dotted with a number of rocks and holms, requiring a skilled pilot to negotiate. Towards the west open up the fine bays of Dales Voe, Laxfirth, Wadbister Voe and Catfirth; and off the point of Hawksness is the Unicorn rock, on which the ship that was chasing the Earl of Bothwell was wrecked (1567).

Facing the bold promontory of the Mull of Eswick stands the Maiden Stack; to seaward the Hoo Stack and Sneckan; and extending eastward a succession of rocks and skerries, which go by the name of the "stepping stones." Passing the bay of South Nesting, we approach the "bonnie isle" of Whalsay, with the fine bay of Dory Voe opposite. Between Whalsay and the land lie a number of isles, the largest being West Linga, while from the outer side, islands and rocks stretch in an easterly direction, the farthest group being called Out Skerries. The largest of these, Housay, Bruray

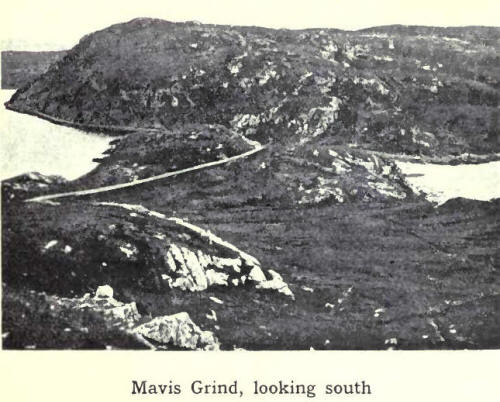

and Grunay, are inhabited; while on a small isle, called Bound Skerry, is erected a fine lighthouse, which shows a bright revolving white light, visible a distance of 18 miles round. Passing Vidlin Voe and doubling the long promontory of Lunna Ness, we reach. Yell Sound. On the right lies the island of Yell ; on the left the triple openings of Swining Voe, Collafirtli and Dales Voe and further on Firths Voe and Tofts Voe, with the ferry of Mossbank between. After OrkaVoe, we round Calback Ness and enter the fine bay of Sullorn Voe, extending about eight miles inland. Only a narrow neck of land separates it from Busta Voe on the west, while a little to the northwards, at Mavis Grind, the distance between Sullom Voe and the Atlantic is only a stone's throw. After Gluss Voe and the pretty bay of 011aberry, Collafirth is reached, and then Burravoe, the farthest roadstead in Yell Sound. Looking back from this point, we view the whole Sound with its many isles and holms, low-lying, and affording good pasture for sheep. The largest are Lamba, Brother Isle, Bigga, and Samplirey. Near Samphrey are the Rumble Rocks, with a beacon to aid navigation.

Returning to Yell Sound, we find on its north side the two harbours of Hamnavoe and Burravoe, in Yell. Proceeding north through the Sound, we pass the bay of Ulsta and the Ness of Sound. From Ladie Voe to Gloup Holm the coast is bold and rocky, with only one inlet, Whale Firth, which runs inland till it almost meets Mid Yell Voe. In the extreme north is Gloup Voe. Blue Mull Sound, which separates Yell from Unst, has the harbour of Cullivoe near the middle and Linga Island at the south entrance. On the east coast of Yell are the fine bays of Basta Voe and Mid Yell Voe, with the island of Hascosay between.

Across Colgrave Sound lies Fetlar, one of the most fertile of the islands. It is elevated towards the northeast, where Vord Hill rises 521 feet. Hereabout the coast is precipitous and very imposing. The principal openings are Tresta Wick in the South and Gruting Wick in the east. Brough Lodge is a calling-place for steamers.

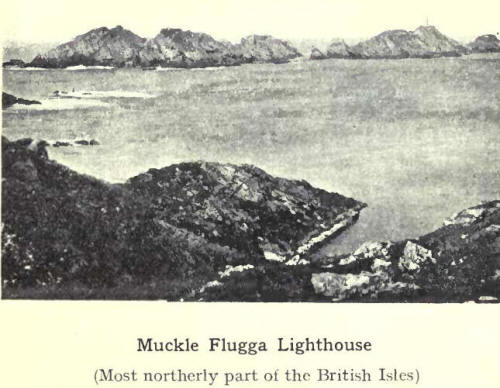

Unst is the most northerly part of the British Isles.

In the south is the harbour of Uyea, cast of which is Muness with Muness Castle. The principal harbour in Unst is Balta Sound, completely protected by the islands of Balta and Huney. Further north is Haroldswick, named after Harold Fairhair of Norway, who landed here on his expedition against his rebellious subjects. After passing the sandy bay of Norwick and rounding Holm of Skaw, we reach the northern extremity of Unst. The heights of Saxa Vord and Hermaness hem in the entrance to Burrafirth. Rising from a group of rocks, about a mile to seaward, is the Flugga, with a fine lighthouse, which shows a fixed light, with white and red sectors. From Hermaness to Blue Mull Sound, the west of Unst is bold and rocky, with only one inlet of importance, Lunda Wick.

8. Round the Coast—(b) Along the West from Fethaland to Fitful Head

A mile or two off the point of Fethaland are the Ramna Stacks, huge rocks like giant sentinels guarding the northern extremity of the Mainland. From this point to the isle of t'vea, and onwards to Ronas Voe, the chief feature of the coast is the high and rugged granite cliffs, which gradually increase in height till the voe is reached. This fine natural Barbour, lying round the base of Ronas Hill, forms, with Urafirth on the opposite side, an extensive peninsula to the westward. The coast line of the peninsula is rugged and much indented, with wonderful caves and subterranean passages, wrought out by the action of the sea, the Grind of the Navir and the Holes of Scradda being the most remarkable. Off the south coast lie the famous Dore Holm with its natural arch, and the Drongs, resembling a ship under sail. Hillswick, in Urafirth, is the terminal port of call for steamers on the west side, and forms a convenient centre for the many fine trout-fishing lochs in the neighbourhood.

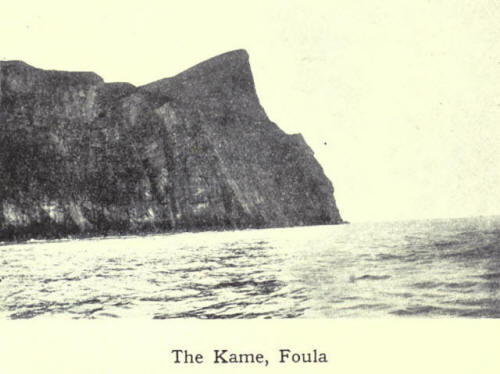

On the east of the extensive bay of St Magnus lies Muckle Roe, with its sea-face of red granite cliffs. To the south are the smaller grazing islands of Vementry and Papa Little, with the channel of Swarbacks Minn between, forming the common entrance to Busta Voe, Olnafirth, Gonfirtli and Aith Voe. Between the last opening and Bixter Voe, on the opposite side, runs an isthmus which connects Aithsting, Sandness, Walls and Sandsting with the other part of the Mainland. The northern side of the peninsula thus formed is pierced by the openings of Clousta Voc, Unifirth and West Burrafirth, while lying off the north-west extremity is the fertile island of Papa Stour, with its high cliffs and beautiful caves, Christie's Hole being the finest. About three miles to seaward are the dangerous rocks of Ve Skerries. The coast from Sandness to Vaila is bold and rocky, the headland of Watsness being the turning-point on this rugged coast. About eighteen miles to the south-west lies the lofty island of Foula. The east side of the island is comparatively low-lying, but the land rises towards the west, where the cliffs tower 1220 feet above the sea. A dangerous shoal, the Haevdi Grund, lies to the east of the island, and it was here that the liner Oceanic was wrecked (1914).

The island of Vaila lies across the mouth of Vaila Sound, and bounds the entrance to the extensive bay of Gruting Voe. From Skelda Ness to Scalloway the distance is about seven miles across an arm of the sea, which runs north and is broken up into many openings. Taken in order, these are Skelda Voe, Seli Voe and Sand Voe ; Sand Sound, the common entrance to the voes of Bixter

and Tresta; Weisdale Voe; Stromness Voe with the tidal loch of Strom; and Whiteness Voe. Lying off the entrance of these two are the islands of Hildasay, Oxna and Papa. Opposite Scalloway, and forming a shelter to its harbour, is the island of Trondra. Further south are East and West Burra and Havra, with the long channel of Cliff Sound on their eastern side. The fertile island of St Tinian, locally known as St Ringans, is joined to the land by a narrow isthmus of sand. To the south lies the isle of Colsay opposite the inlet of Spiggie. The high cliffs of Fitful Head form the termination of the west, as Suinburgh Head of the east. Between lies the fine sandy bay of Quendale, with its background of sand dunes and rabbit warrens, while to the south are the islands of Lady's Holm, Little Holm and Horse Island.

9. Climate

As Shetland is entirely insular, and surrounded by ocean currents considerably warmer than those of other places in the same northern latitude, the climate is wonderfully equable, extremes of heat and cold being rare. The prevailing winds come from the south and west, laden with warm moisture from the Atlantic to temper the atmosphere. Added to that is the general "drift" of the Atlantic towards the British Isles. Of this warm current, Shetland gets its share.

When the air becomes laden with moisture, it is lighter than dry air, and in consequence the barometer is low. Wet and stormy weather usually follows. When the air is clear and dry, then the barometer is high, and good weather may he expected. The former is called cyclonic, and the latter anti-cyclonic types of weather. The atmospheric pressure varies as the storm moves onward ; hence there is usually a falling barometer till the storm is over, succeeded by a rising barometer. The cyclone, as the storm is called, has two motions, a circular motion opposite to the hands of a clock, and a general forward movement as a whole, usually from some point west to some point east. In winter the deficiency of atmospheric pressure in the neighbourhood of Iceland accounts for the procession of westerly gales from the Atlantic during that season, causing the southerly type of wind to prevail over Shetland. In summer the area of low pressure is over Central Asia, which produces a northerly type of wind over the islands, and this corresponds with the dry season of the year.

Take a typical cyclone moving from the Atlantic, and passing, as it often does, between Shetland and Iceland. The weather may be unnaturally warm fQr the season of the year, the sky becomes overcast, the wind backs to the south or south-east, and the barometer falls rapidly. Other premonitory signs inay be a halo or "broch" round the sun or moon ; aurora (Merrie Dancers) high overhead; or a heavy swell in the sea. Wind and rain follow; after a time there may be a sudden lull; the wind shifts to the west or north ; the barometer rises briskly and the clouds clear away, often with a strong gale of wind.

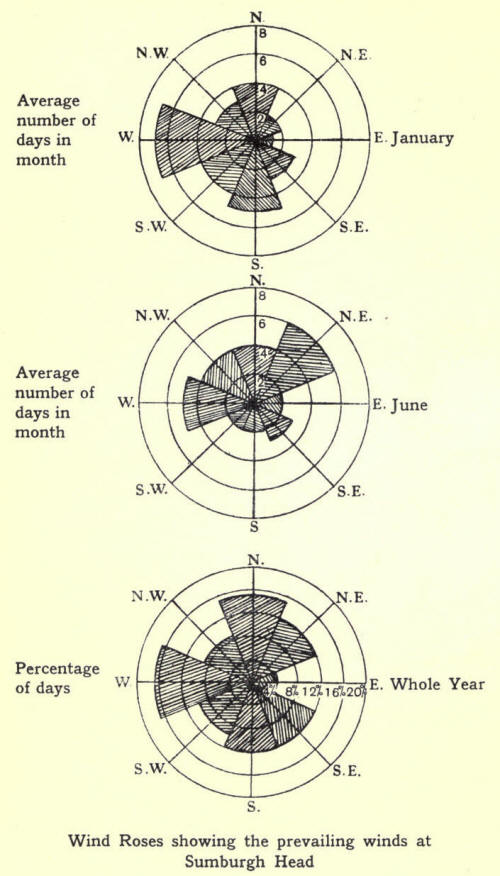

From November to February the prevailing winds are from the south and west, averaging about 5 days for each month, while October has an average of 7 days from the north. From March to June, the prevailing winds are from the north and north-east, which accounts for the cold spring and late summer, the

average being about 4¾ days for each of these months. July is equally divided between west and north, having

days of each; while August has a total of 5 days from the north and September 6 from the west. The wind-rose shows that for the whole year the west wind prevails with 17 per cent. while the east has only 4. January has 7 days of west wind and only 1 of east; June has 6 days from the north-east, and 4 each from north and north-west. The average number of days in the year with calm weather is 27, with gales 37.

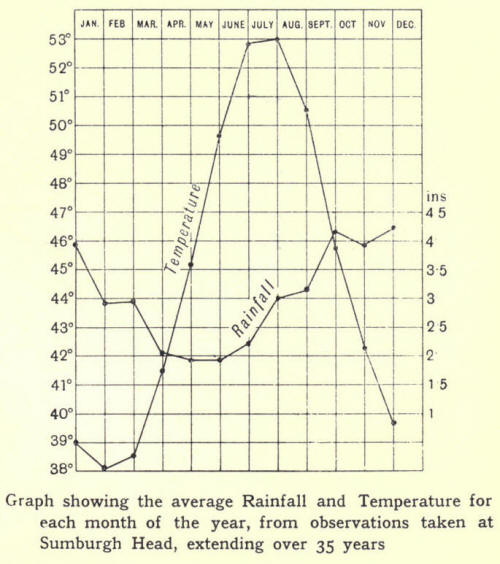

As might be expected from its insular position, the climate of Shetland is moist, and the annual rainfall is about 37 inches, while the number of rainy days in the year amounts to 20-1. This is the record for Sumburgh Head, extending over a period of thirty-five years; but of course the rainfall varies considerably in different parts of the islands. The wet period of the year embraces the months of October, November, December and January; while the dry period, if it can be called such, includes May, June and July—May being driest. Heavy falls of snow are not uncommon; but owing to the sea-breezes and changeable weather, snow seldom lies for any length of time.

The climate is somewhat cold, the mean temperature for the year being 44.7 degrees, while the mean monthly temperature varies from 38° in February and March, the coldest months of the year, to 53° in August, the warmest month. It is found that this mean annual temperature closely approximates to the temperature of the sea (from a depth of 100 fathoms to the bottom) between the Hebrides and Faroe. Thunderstorms are not frequent, and heat waves are usually followed by fog, which is very prevalent in summer and greatly impedes navigation round the coast. The month of May has an average of 8 days of fog, June 12, July and August 10 each, while the whole year shows a total of 75 days.

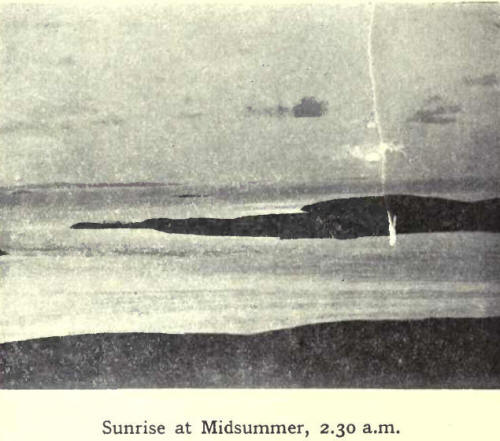

Winter in Shetland is dark and stormy; but this is

to a certain extent compensated for by the long days of summer, from the middle of May to the end of July, when darkness is unknown. That season gives to the islands the poetic name of the "Land of the Simmer Dim."

10. People—Race, Language, Population

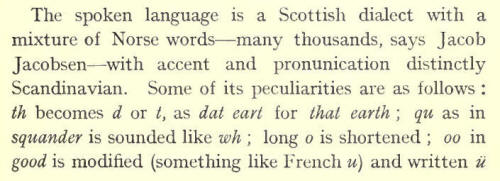

That Shetland was inhabited from remote times is evident from the number of primitive stone implements found all over the islands. The rude hammer and axe; the finely-polished celts and knives; the stone circles and brochs; the burial mounds, with urns and stone coffins—all bear mute testimony to successive stages of progress towards civilisation. Who the earliest inhabitants were it is not easy to discover; but it is generally agreed that for a number of centuries the Picts held sway till supplanted by invaders from Norway. Norse influence began with Viking raids, and then towards the end of the ninth century assumed the form of conquest. Scandinavian domination lasted till 1468. During this period the people were Norse to a large extent in blood and altogether in language, manners and customs; and although Scottish influence has brought about many changes, yet the Shetlander still retains many of the Norse characteristics of his ancestors.

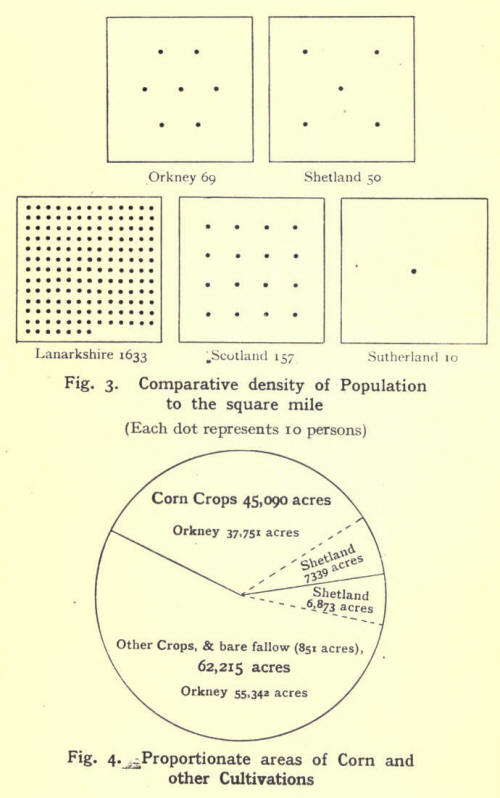

A century ago the population was 22,379, and reached its maximum (31,670) in 1861. After that it gradually decreased, chiefly owing to emigration, to 27,911 in 1911. The density is about fifty to the square mile.

11. Agriculture and other Industries

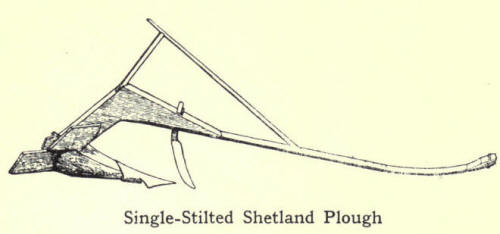

As an agricultural county, Shetland is comparatively poor, and that for various reasons. Although in certain districts the soil is of good quality, and produces crops that compare favourably with any Scottish county, yet much of the land may be classed as indifferent or poor. Only 4 per cent, of the whole land surface is arable. Permanent pasture might be 10 per cent. Fourteen per cent. may thus be taken as the limit of profitable agriculture. The other 86 per cent. is used for grazing. Shetland is a crofting county, but most of the holdings are to small to support a family, unless the men have some subsidiary employment, either as fishermen or sailors. Some 56 per cent, of the male population are classed as farmers or fishermen, or both combined. The result of this divided attention is seen in the backward state of cultivation, up to very recent years. Another important factor was insecurity of tenure. Before the passing of the Crofters Act in 1886 there was no security, and in many cases where a crofter improved his holding. he had to pay increased rent for his pains. But matters are now growing better. The crofter has a fair rent fixed; his tenure is secure, so long as lie conforms to certain legal requirements; and with increased facilities for placing his produce in the market, he has every inducement to give of his labour and intelligence to agricultural work. Up-to-date methods and tools are taking the place of primitive ways and out-of-date implements; and the Board of Agriculture is helping to educate people into better methods of agriculture and dairying. School gardening, now almost universal, is also doing much to encourage the production and use of garden vegetables.

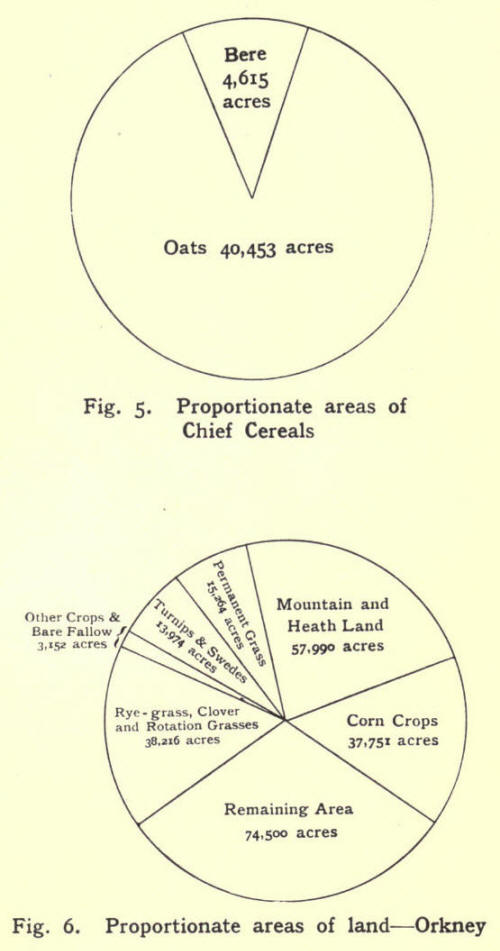

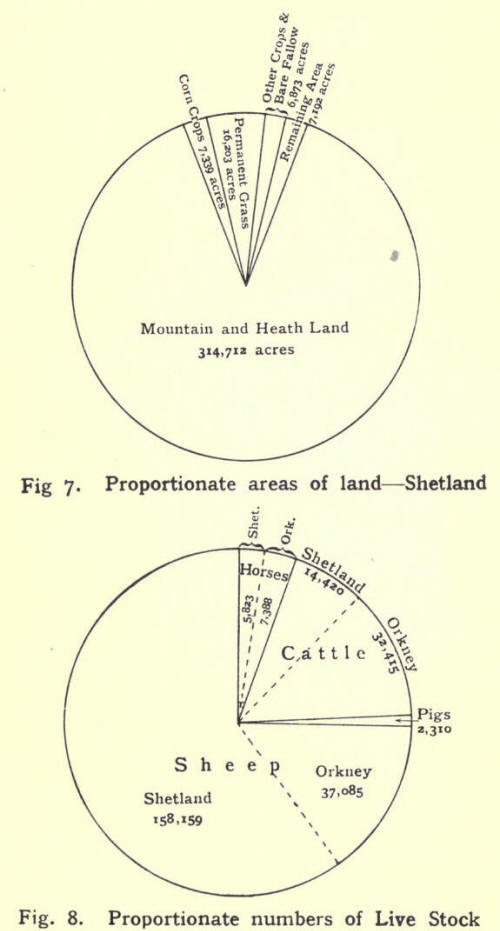

There are 352,319 acres of land in the islands; and of these, only 15,352 acres are under cultivation; while 35,472 acres are laid down to permanent grass. The number of holdings in the islands is 3550, giving an average of 14.3 acres to each holding. Of these, there are 793 under 5 acres; 2021 between 5 and 15 acres; 563 between 15 and 30 acres; 97 between 3o and 50 acres ; 4o between 5o and Zoo acres ; 3o between zoo and 300 acres; and 6 over 300 acres. It will thus be seen that nearly 98 per cent. of the holdings are crofts under 50 acres in extent. Of the arable land, oats is the principal product, extending to 7291 acres, or nearly

one-half; while bere is grown on 1035 acres. Potatoes take up 2795 acres and turnips the half of that, while ryegrass covers 1067 acres. There are 288,962 acres of hill pasture or "scattald" on which each crofter has the right to graze a certain number of sheep, ponies or cattle.

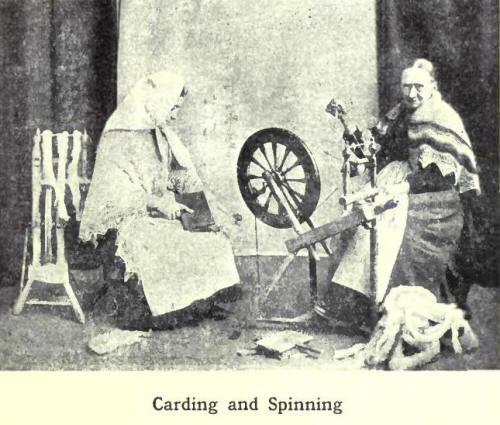

The native sheep are diminutive in size; but the wool, which is made into shawls and other articles, is well known for its softness. Practically every Shetland woman is a knitter; and although this may be reckoned a subsidiary employment, it is a very important one. Large quantities of knitted goods are sent out of the islands every year ; and the money obtained for them is a welcome addition to the too often scanty, earnings of the crofter-fishermen. Over 2000 women are engaged in agriculture, and nearly 3000 in making hosiery.

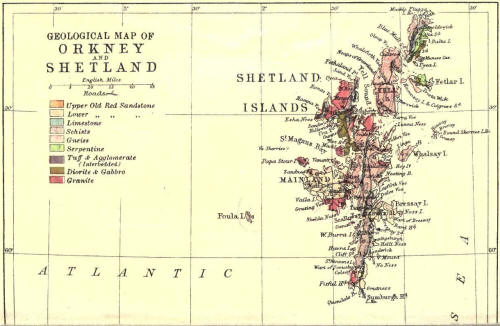

Besides the common grazing ground used by crofters, there are large tracts enclosed as sheep-runs, in which black-faced and other breeds are raised for the southern markets. The total number of sheep in the islands in 1912 was 162,090.

The native breed of ponies—some of them as low as seven hands—is well known. In days gone past they served a useful purpose as beasts of burden; but the coming of roads and wheeled vehicles demanded a larger and stronger type of animal; and now they are bred chiefly for export, to be used in coal mines and for other purposes. The picturesque sight of a long string of these hardy and intelligent little animals, tied head and tail,

each with "kishies" fastened to "clibbers," and the whole strapped up with a "maishie," wending their may Homeward with a load of peats, is now almost a thing of the past, except in districts where roads are few. Horses, large and shall, number 5827.

The native cow, like the sheep and the pony, is also diminutive; but under favourable condition, gives a good supply of milk of excellent quality. There are 15,932 cattle in the islands, of which 6027 are milch-Cows.

Except farming and fishing—with their allied occupations—industries are few in Shetland. Lerwick has two saw-mills. Freestone is quarried at the Knab near Lerwick and at the Ord in Bressay. Copper ore of good quality used to be mined at Sandlodge, and chromate of iron in Unst ; but the low prices for these made working unprofitable, and now only a small quantity of chromate is raised. Another bygone industry is the making of kelp from seaweed—once a source of considerable wealth. It may be revived, as the war (1914) caused a scarcity of potash for use in farming.

12. Fishing

For centuries it has been the custom --lately, however, to a less extent—for the crofter-fisherman to fish in the summer and to work 'on his farm during the rest of the year. Every voe and creek had its fleet of small boats engaged in line fishing; but owing to the depredations of trawlers on the fishing grounds and other adverse circumstances, the system gradually declined. Line industry has now shrunk to very small dimensions, and herring fishing has taken its place. At a few creeks round the coast, small boats still engage in line fishing, while at Lerwick and Scalloway there is a considerable fleet of boats engaged in haddock and long-line fishing. Haddocks and halibut are sent in ice to Aberdeen, while other kinds of fish are salted and dried for export. Lerwick and Scalloway have also kippering kilns.

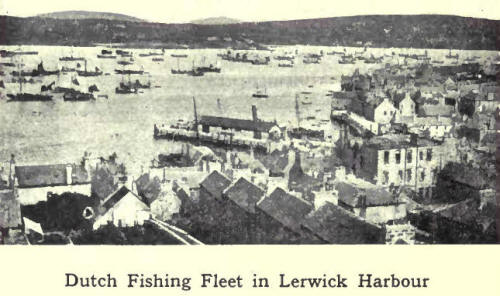

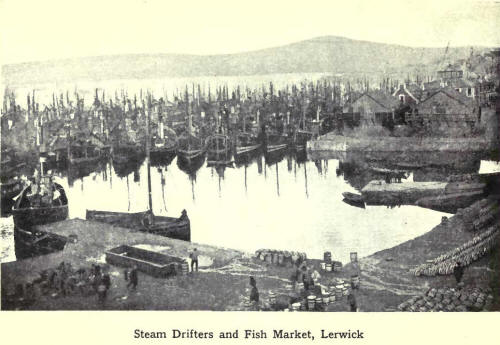

From its position and other natural advantages, Lerwick is an ideal fishing centre, and is now one of the chief fishery ports in Scotland. The Harbour Trustees

have provided pier accommodation, erected a fish market, and in other ways met the demands of this industry.

Round the harbour and along the shores of Bressay Sound a large number of curing yards are erected, each with its wooden jetty, at which the herrings are discharged. There they are taken in hand by a staff of men and women, who clean and salt them in barrels.

They used to be shipped to the Continent--chiefly to Russia and Germany—through Hamburg and the Baltic ports of Petrograd, Libau, Riga, Stettin, honigsberg, and Dantzig.

The fish-offal is collected from the various fishing stations and taken to the factories in Bressay, where up-to-date machinery converts the raw material into articles of commerce, as fish meal for feeding cattle and pigs; oil for tanning; stearin for soap-making and manure.

Other fishing ports are Baltasound, Sandwick, Whalsay and Scalloway. There and at other centres herring -fishing is carried on by sailing boats as well as steam drifters. In other districts deserted curing yards may be seen—relics of the formerly prosperous fishing stations.

The number of boats of all kinds fishing round the Shetland coast in 1913 was 952, and of these 551 were sailing boats with 2332 native men and boys. The number of drifters working from Lerwick and other ports was 380, with 3800 men, mostly Scottish and English fishermen. In addition, there were 5 drifters and 16 motor-boats owned locally, with 99 native and 10 non-resident men engaged. The total value of all these vessels, with their gear, was estimated at £1,045,839. The total quantity of fish landed amounted to 38,585 tons, valued at £347,894. This included shell-fish, herring, mackerel, ling, cod, tusk, saithe, haddock, whiting, halibut, skate, plaice, and dabs. Besides the 6241 persons actually engaged in fishing, this important industry gave employment to about 4000 other workers—gutters, coopers, carters, labourers, and sailors.

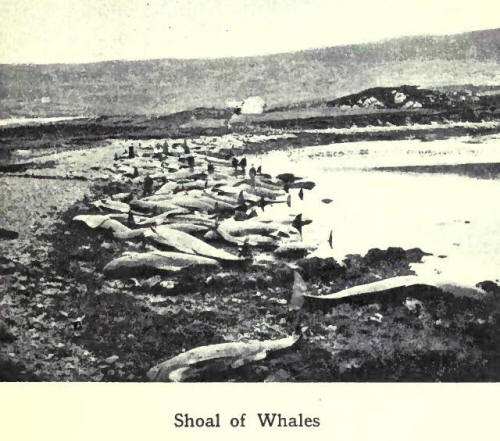

Shetland had three whaling stations, Olna Firth,

Ronas Voe, and Colla Firtli. The men employed were mostly Norwegians.

13. Shipping and Trade

Long after Shetland was annexed to Scotland, trade and friendly intercourse continued to be carried on with Norway and other countries across the North Sea. Dutch and Flemish fishermen also frequented the islands, and established a considerable trade, exchanging foreign produce for fish and articles of native manufacture. ']'here was regular communication with Bergen, Hamburg, Bremen and other Continental ports; and

people from Shetland often travelled to Scotland and England by way of the Continent. As time went on, more direct communication was established with Scotland by means of sailing vessels. Trade was carried on by these till the advent of a steamship in 1836, when the paddle-boat Sovereign began to lily between Granton and Lerwick once a fortnight—afterwards once a week—calling at Aberdeen, Wick and Kirkwall. At the present time four steamers regularly arrive from Leith or Aberdeen each week during summer. One of these makes a weekly trip to Scalloway and ports on the west side. Lerwick is the port of call on the east. In addition to these, another of the North of Scotland Company's steamers does the coast-wise trade on the east side and to the North Isles.

All goods, mails and passengers to and from Scotland are carried by this company's steamers. The imports consist of meal and flour; tea, sugar and butter; feeding-stuffs for cattle ; and the miscellaneous articles that form the stock-in-trade of the draper, the grocer, the ironmonger, and the general merchant's store in town and country. The exports include eggs, dried and fresh fish, wool, hosiery, sheep, ponies and cattle, and . cured herrings. Timber is brought direct from Norway. Coal, salt and empty barrels are imported in specially chartered vessels.

14. History

Little is known for certain of Shetland in early times. If by Thule, visited and described by Pytheas of Massilia, the ancients meant Shetland, then the first mention of the islands in our era is when Tacitus, telling of Agricola's fleet in 84 A.D. says "Dispecta est et Thule," assuming that it was really part of Mainland that the sailors descried in the dim distance. Irish missionaries christianised the natives in the sixth and seventh centuries. The nearness of the islands to Norway naturally led to visits from the Viking raiders and finally to conquest and settlement by them in the ninth century. The Norsemen found two races of people—the Peti or Picts, and the Papae, descendants of the Irish missionaries. Whether these were exterminated or absorbed by the invaders is disputed; but Christianity disappeared before Odin, Thor and other Scandinavian deities.

For several centuries after this, the history of Shetland is hardly separable from the history of Orkney, and that has been already narrated. Though both groups of islands formed one earldom, Orkney was the predominant partner. Shetland received scant attention except as a recruiting ground for fleets or armies. From 1195 to 1379 Shetland was disjoined from Orkney; and, while the latter came more and more under Scottish influence, the former remained under Norse. It was during the period of separation that Norse influence impressed itself most strongly on Shetland.

Norse Shetland had its Althing or Parliament, meeting on the holm in Tingwall Loch under the presidency of the Foud. Each district had its lesser Thing (as Aithsting, Nesting) and its under-Foud, who selected Raadznen or Councillors, and was assisted by the Lawmen or Legal Assessors. The Lawrightman superintended the weights and measures—an important office, since rents and duties were paid in kind. The Ranselman was a kind of parish constable.

15. Antiquities

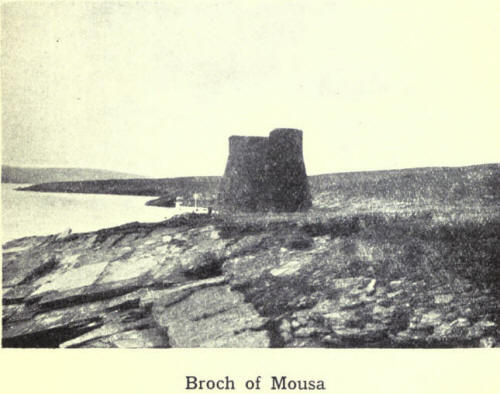

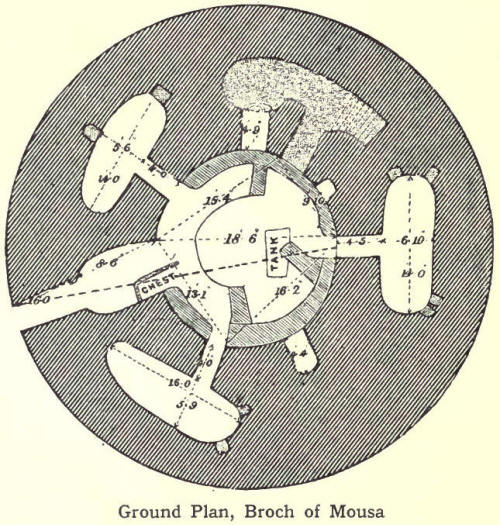

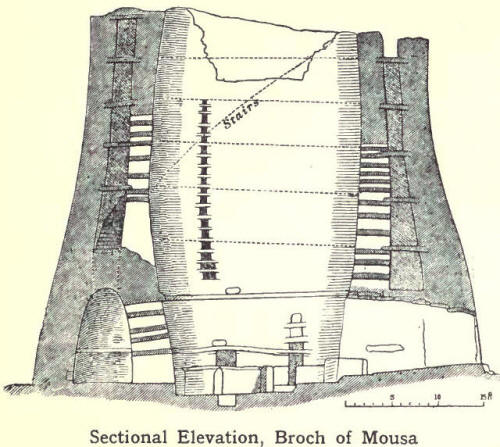

The most conspicuous remains of antiquity in the islands are the Pictish castles or brochs, of which there

are seventy or eighty. Most of them are in ruins; but the one notable exception is that of Mousa Castle, the most perfect of its kind in existence. Another broch is in the loch of Clickimin. Though only a remnant, it conveys a good idea of the massive structure of these buildings.

Standing stones occur in every parish. Other prehistoric relics are the stone circles, the earth-houses or underground dwellings, and "pechts knowes." The

last are artificial mounds of burnt stones and earth. In some of these are found stone coffins or cists, in others urns containing the ashes of the dead.

Implements and weapons of the Stone Age are being continually unearthed. Some are rough and include hammers, clubs, whorls for spinning, stones for pounding corn, whetstones, vessels for liquids. Others are polished, and show a great advance on the rough in

workmanship. These include celts or axes of porphyry or serpentine, locally known as "thunderbolts" and held in veneration by the finder. Another polished weapon is the knife, said to be found only in Shetland.

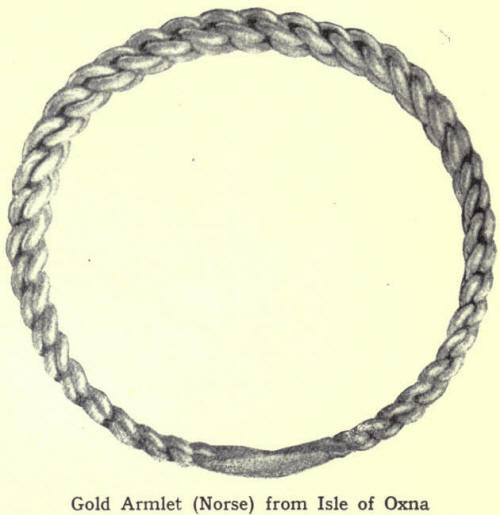

Gold, silver and bronze ornaments of the Viking Age are occasionally discovered—one of the most recent and beautiful a bracelet of gold in the isle of Oxna.

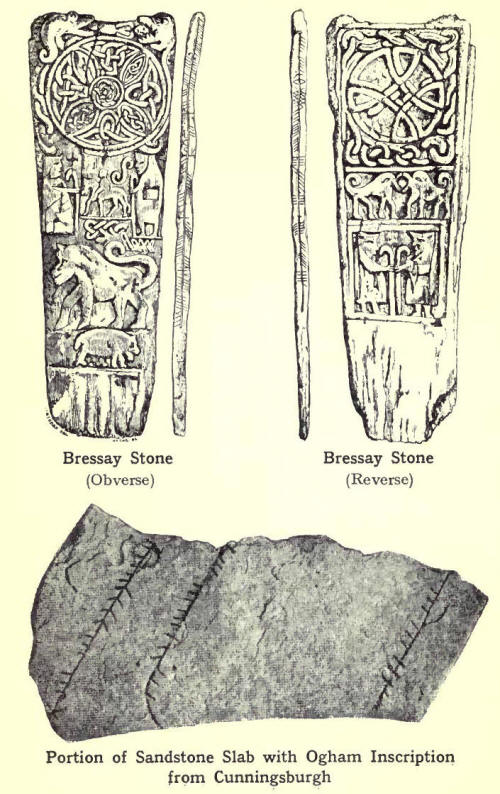

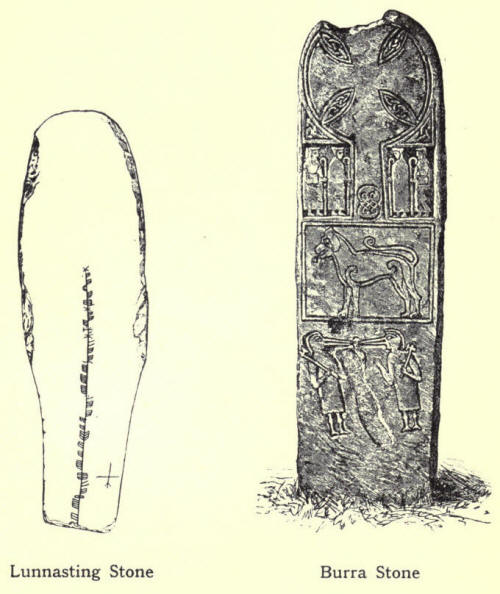

Inscribed or sculptured stones are of two kinds—Celtic, and Norse or runic. Examples of the Celtic are the Bressay Stone, the St Ninian Stone, the Lunnasting Stone, with Ogham inscriptions, and the richly sculptured monument found in Burra Isle. These

are all indications of the Christianity of the pre-Norse days. Four runic stones have been discovered, three in Cunningsburgh and one in Nortlimavine.

16. Architecture

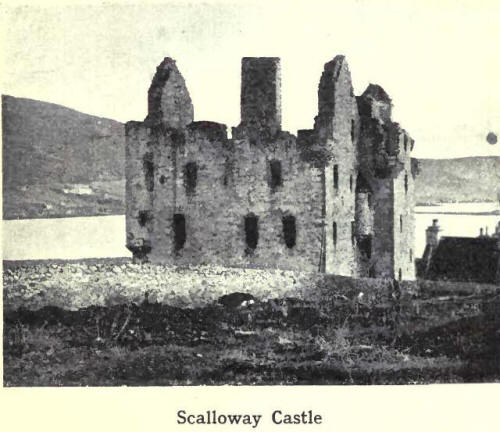

Scalloway Castle, and Muness Castle in Unst, are the only two feudal structures in the islands.

Scalloway Castle was built by Earl Patrick Stewart in 1600, at a time when Scalloway was the capital and the only town in Shetland. Over the gateway was a Latin inscription, adapted from the New Testament contrast between the house founded on a rock and the house founded on the sand-

At Sumburgh is the ruin of Jarlshoff, once a residence of Lord Robert Stewart, and rendered famous in Sir Walter Scott's novel The Pirate.

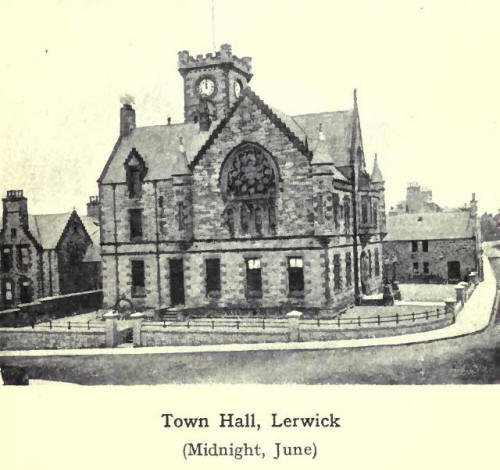

The only building of architectural significance in

Lerwick is the Town Hall, a handsome Gothic building, erected in 1882. Its external decorations include the arms of the town and of the nobles who were connected with the government of Shetland. The main hall is the chief centre of interest. Its beautiful stained-glass windows present a magnificent series of pictures representing the history of the islands from the time of the Norwegian conquest to James III of Scotland, who married Margaret of Denmark.

17. Communications

Till the middle of last century Shetland was almost devoid of roads. All traffic had to go by water, while travelling by land was on foot or on horseback over moorland tracks. The failure of the potato crop in 1846 and following years caused much distress in the islands ; and the food and money sent by the Board for the Relief of Destitution in the Highlands enabled labour to be hired for road-making. Between 1849 and 1852 about 120 miles of roads were constructed, joining Lerwick with Dunrossness on the south, with Scalloway and Walls on the west, and with Lunna, Mossbank and I lillswick on the north ; while a road 17 miles long was constructed through Yell. Under the Zetland Roads Act (1864) roads were improved and extended all over the islands. The County Council now manages all roads and bridges.

The southern terminus of the main road is Grutness, near Sumburgh. From this point to Lerwick the road skirts the east side of the island, with branches leading to various districts. From Lerwick the north road begins by climbing the hill of Fitch. At the bridge of Fitch a branch diverges to Scalloway ; and further on, at Tingwall, is the junction of another route to the ancient capital. Here the main road bifurcates, one fork going in a westerly direction through Whiteness, Weisdale, Aithsting, Walls and Sandness, and terminating at Huxter. The other fork after passing Girlsta and Sandwater, enters the dreary Lang Kame, a stretch of five miles without a single habitation, where, says superstition, the benighted traveller may meet "Da Trows," the goblins of Norse mythology. The road then runs by the Loch of Voe to Olnafirth Kirk. Here it divides—going on the right by Dales Voe to Mossbank, on the left to the narrow neck between Busta Voe and Sullom Voe and thence by Mavis Grind past Punds Water. Again it branches, to Ollaberry on the right and Hillswick on the left. In Yell the chief road runs from Burra Voe to Cullivoe in the north-east. The trunk road in Unst—the best in the islands—stretches from Uyeasound. to Norwick.

18. Roll of Honour

Although Shetland has produced no names of worldwide celebrity, yet many sons of the "Old Rock" have risen to distinction both at home and abroad.

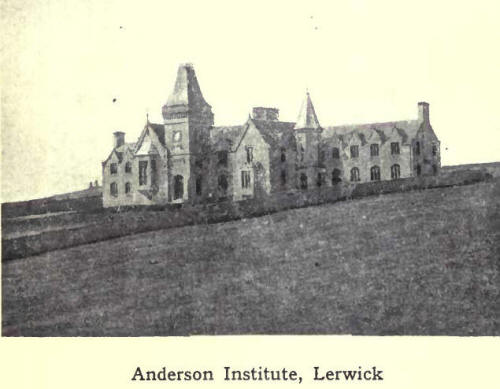

The first place must be given to Arthur Anderson, (1792-1868), who, commencing life as a humble fish-worker at Gremista, near Lerwick, was in 1840 one of the founders of the P. and O. Steamship Company, and ultimately its chairman. Much of his wealth he spent on Shetland. He established the first newspaper in the islands—The Shetland Journal; he started the Shetland Fishing Company, which largely helped to emancipate the crofter-fishermen from their bondage to the landlords ; he introduced Shetland hosiery to the outside world; he was influential in securing steam communication between the islands and Scotland: and,

not to mention more of his benefactions, he founded the Anderson Educational Institute, which is now administered by the Education Authority as a Higher Grade School and Junior Student Centre for the county. Another benefactor was R. P. Gilbertson, a colonial merchant, who presented the Gilbertston Park to Lerwick and founded the Gilbertson Trust for the benefit of Shetlanders.

The islands boast a goodly array of writers, and among these the Edmonston family stands conspicuous. Dr Arthur Edmonston 1775-1841) wrote A View of the

Ancient and Present State of the Zelland Islands; his brother Laurence (1795-1879) was a distinguished Scandinavian scholar and the author of many papers on natural history; Laurence's son, "Thomas, born in 1825, was the discoverer of the Shetland plant arenaria Norvegica, and the author of a Flora of Shetland. At the age of twenty he was elected Professor of Botany and Natural History in Anderson's College at Glasgow; but next year he was accidentally shot dead in Peru, while on a scientific expedition to the Pacific; Thomas's brother, Biot (1827-I906) was joint-author with his sister Mrs Saxby, of The Home of a Naturalist. Dr Saxby wrote The Birds of Shetland. Thomas Gifford of Busta, who died in 1760, was the author of Historical Description of the Zetland Isles; Dr Robert Cowie, of Shetland: Descriptive and Historical; Dr Copeland, of A Dictionary of Medicine; Miss Spence, of Earl Rognvald and his Forebears, and a Memoir of Arthur Laurenson, a scholar deeply versed in Scandinavian lore; Gilbert Goudie, of Antiquities of Shetland, and other works; and John Spence, of Shetland Folk Lore. Of minor poets and vernacular writers we may name Basil R. Anderson; Laurence J. Nicolson, "The Bard of Thule" George Stewart; T. P. Ollason; and J. B. Laurence.

Of men who have risen to distinction in the Government service, the best known is Sir Robert G. C. Hamilton (1836-1895), a son of Dr Hamilton of Bressay. He was at various times Accountant-General of the Navy, Under-Secretary for Ireland, Governor of Tasmania, and Chairman of the Board of Customs.

19. The Chief Towns and Villages of Shetland

(The figures in brackets after each name give the population in 1911, and those at the end of each section are references to pages in the text.)

Balta Sound is a fishing port on the east of Unst. It was formerly a prosperous centre for herrings. (pp. 123, 142.)

Hillswick is a seaport in Northmavine parish in the northwest of Mainland. Hillswick Voe affords sheltered anchorage for vessels. (pp. 125, 156, 157.)

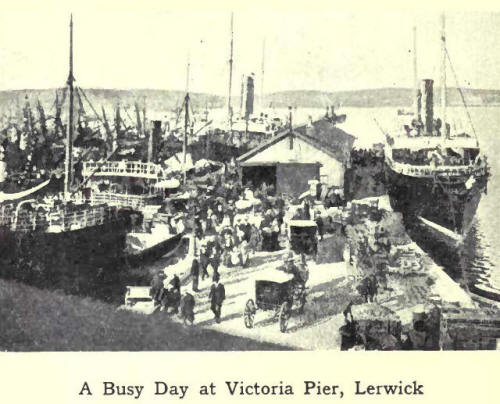

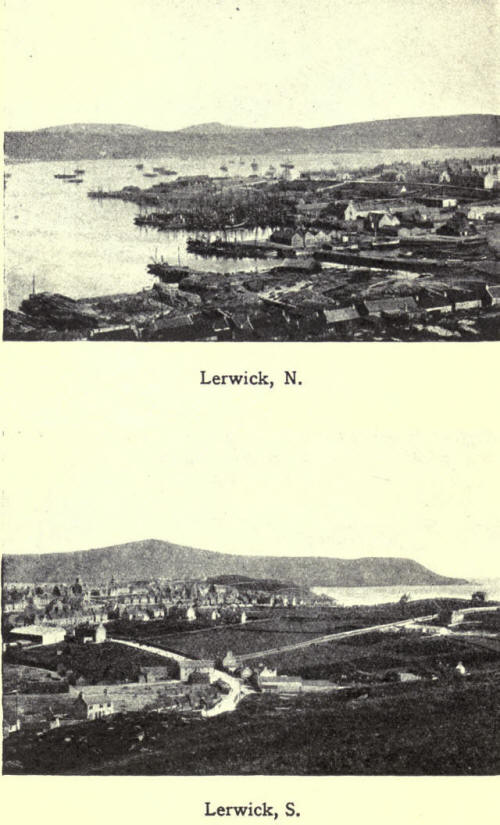

Lerwick (4664), the capital and the only burgh of the county, and the most northerly town in Britain, lies on the west side of Bressay Sound, which forms a safe and commodious harbour. During the Dutch War, Cromwell built and garrisoned the fort. This may be taken as the beginning of the town. In 1781 the fort was put into a state of defence, and named Fort Charlotte in honour of George III's Queen. It is now a Coast Guard Station and Royal Naval Reserve Headquarters. The Old Town, built on the side of a hill facing the harbour, has one narrow and irregular street running parallel to the shore, with numerous lanes branching off at right angles. Some of the houses at the south end of the town are built right into the sea; but elsewhere, the shore has been reclaimed, and an esplanade and wharves take the place of the "Lodberries" of former times. Victoria Pier (erected in 1888), Alexandra Wharf with the Fish Market, and the Boat Harbour, are among the latest harbour improvements. The New Town, which lies on the landward side of the hill, has wide streets and modem houses, the Central School being the principal building; while near by is the Gilbert Bain Hospital. The Docks are situated at the north end of the town, and here also are boat-building sheds, saw-mills and barrel factories. Adjoining the

Anderson Institute is a Hostel for country girl-bursars attending the Institute. This handsome building, the gift of Robert H. Bruce, Esq., of Sumburgh, is the first building of its kind in Scotland. Lerwick has two weekly

newspapers—The Shetland Times and The Shetland News. At Sound, in the vicinity, is a Government wireless station. (Pp. 103, 118, Ito, 139, 140-4-5, 155-6-7-9.)

Scalloway (824), an ancient village, was at one time the capital. It is the chief port of call for steamers on the west, and is a centre for herring and white fishing. The Castle is the chief object of interest. (pp. Io8, 110, 126, 139, 140-2-5, 153, 156.)

Sandwick, in Dunrossness, is a busy fishing centre. (pp. 117, 142.)

You can read the complete book in pdf format here

Shetland Fireside Tales

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION.

When about 14 years ago the Author of "Shetland Fireside Tales" had such misgivings regarding his first literary effort that even the initials attached to the work were a little misleading, he little thought that ever a second edition would be asked for. Not only, however, was the first edition readily taken up, but for many years past a desire for a second has been expressed, both in this country and America. This affords another example of how an Author, who writes for fame, sometimes does not obtain it, while another with no such expectations, but being simply and humbly desirous to express what he knows and feels, finds in the community of human thought and feeling a response to his own. It adds not a little to the Author's satisfaction that in issuing a second edition native publishers can share in any credit due to this as a native effort.

Notes to Shetland

Fireside Tales

Chapters I to

V

Chapters VI

to X

Chapters XI

to XV

Chapters

XVI to XX

Chapters

XXI to XXIV

Poems and

Stories

Shetland Folk-Lore