|

THE records of the white

man’s history make small account, if any, of the injustice meted the red

man. Its “talking leaves” are nearly always those of the forked tongue.

Many and many an Indian battle has been misrepresented in the narration

of the details and in the account of the cause. I personally know this

statement to be fact. I have particularly in mind the events that led up

to the so-called *'battle” of the Washita:

In the autumn of 1868 a

band of soldiers in Kansas raided a peaceful village of Cheyennes. The

women were forced to endure the most fiendish treatment before they—like

the children and the men—were horribly mangled. They were attacked and

killed simply because they were Indians. This is the truth.

When the news of the

massacre reached the tribes camped at Fort Dodge and Fort Lamed, they

were so filled with rage and resentment they started immediately on the

warpath—quite as the white men would have done under like circumstances.

It was just before the

time of the big buffalo hunt, when General Philip Sheridan, Commanding

Officer of the Department of the Southwest, sent a Caddo Indian—Caddo

George—with a message to the Cheyennes, Arapahoes, Kiowas, Comanches and

Apaches.

The message said that it

was the wish of the Great Father at Washington that there should be no

more war, and that if they would come in and camp on the Washita River,

there would be peace.

At this the people were

glad. They had been chased across the plains for several successive

summers by the soldiers, and at the prospect of living in peace,

undisturbed even for a season, there was general rejoicing among the

tribes.

So, after a successful

hunt, they went into camp on the Washita. Everything was made snug and

comfortable before the approach of cold weather, and without fear of

disturbance from the soldiers—for had not the messenger brought the word

direct from General Sheridan?

There was nothing to do

but to enjoy. The young men gave themselves up to singing and dancing at

night and to dreaming in the daytime; the old men to telling stories of

the days before the intruding white man came, and to playing their games

in the fireglow; while the merry laughter of children at play and the

voices of happy women at work, all spoke of peace and good will. Even

the savage dogs became amiable from much feeding, and the boniest ponies

grew fat from plenty of grass.

In every tepee were fire

and meat and merry hearts.

Came a north wind. It

made the water of the river hard. It shook snow from its wings. But the

fires burned the brighter, the robes were drawn the closer, and the

laughter was all the cheerier.

My foster-mother, whose

mother was a Cheyenne, had taken us children on a visit to the Cheyenne

camp but a short distance up the river. There was a feast in

Grandmother’s tepee while the wind howled and the snow swirled and

drifted and the sparks flew upward.

It was far into the night

when the camp grew quiet and the fires grew dim and I snuggled down

under the soft robes close to Mother. I fell asleep thinking of the fun

I would have with the boys on the morrow, when the sun should reach the

place of short shadow.

Crack! Crack! Crash!

Crash! came shots and volleys mingled with strange shouts. The warriors

in our tepee sprang up, with ready guns in hand. Their practised ears

told them at once the dread meaning of it all.

Hastily buckling on their

belts, they gave their war cries and plunged out into the snow to meet

the invading enemy. For a little while the women remained with us

children in the tepee. But guns and voices grew louder, came nearer, and

the shouts of soldiers and the screams of women and children mingled

with the flash and crash of guns, the clatter of horses, the twang of

bowstrings and the defiant whoops of the surprised but stout-hearted

warriors. The camp was in the death grapple. The soldiers fought for

glory; the Indians for home and loved ones.

Bullets whizzed through

the tepee and Mother pushed us children out of it ahead of her so that

none should be left behind.

In the snow, which was

waist deep to me, I became separated from her and the others in the

confusion, and I lost my robe. A soldier on horseback came dashing

toward me, and I dived under a pile of brush. His gun blazed as he

passed me. The noise was carried on farther down the river but I lay

still, shivering from the cold—I was naked but for a small piece of

blanket about my loins.

Calling to the women and

children came an old warrior with his arm dangling at his side. I

crawled out to him.

“Come on, boy,” he said,

“we’ll go yonder with the women and children and die with them.”

He took me to Mother and

the other children. He had gathered a number of them into a little clump

of trees. I huddled down between Mother’s knees and she wrapped the

bottom of her robe about me. I was just beginning to feel warm, when

little See-Seh —Arrow-head, my foster-brother—fell limply against me.

Mother took him in her arms. The blood was trickling from his breast. As

he was dying she called to the other women,

“The soldiers are going

to kill us all. Let us go upon the long trail with a song.”

They joined in the death

chant while women and children were struck down all about us.

The few survivors were

finally driven off like a herd of animals. A man on muleback drove us,

and he swung and lashed out at us with a lariat all the way to the place

where Custer sat upon his horse and waited.

My own father, California

Joe, was General Custer’s chief of scouts in that fight, and I believe

it was he who drove us.

We huddled down again in

the snow, and watched the smoke and fire coming from the tepees. The

soldiers were destroying them, together with the provisions and the

winter robes.

After a while there was

the sound of many guns at some distance from us. We thought the soldiers

were killing the warriors whom they had taken prisoners; but they were

only shooting the horses. They killed nearly a thousand.

It must have been in the

afternoon when the soldiers started us down the river. I walked a while,

but my feet were frozen and my whole body was so numb, that I fell down

in a snowdrift. My older brother, Tsaeepahgo (One Horse), took me upon

his back and carried me. When Mother saw how cold I was, so cold that I

could scarcely cling to his neck, she took the robe from her shoulders

and wrapped it around me. Otherwise I might never have come through the

suffering.

In history—the white

man’s history—the “Battle of the Washita” is called a great victory. But

that is always the way. White men’s massacres of Indians are always

victories; Indian victories over white men always massacres. Indian

strategy is treachery; white men’s treachery, strategy.

Eight years later General

Custer led the Seventh Cavalry into the Sioux country to do to them what

he did to our people. The outcome of that raid is alluded to as “The

Custer Massacre.” It was not a massacre. It was a battle and an Indian

victory. Chief Gaul simply outgeneralled Custer, and in defending their

families and their homes, the warriors did to the invading white men

exactly what the invading white men would have done to them.

But if ever there was a

massacre of human beings under heaven, it was in our camp on the

Washita, on November 27, 1868, when one hundred and three men, women and

children were killed, after being promised peace and safety. But one

side of the Indian’s story has been told, and that side the white man’s.

So it is my belief that the foregoing true account of the facts has

never before been written.

We had nothing to eat on

the day of the battle and at night we slept in the snow without fire. On

and on the soldiers drove us through the snow while the children moaned

and the women bit back their grief-cries for the sake of the men, who

walked along,, grim-faced and silent.

My frozen feet were so

sore and swollen, I could not stand. The older boys carried me until

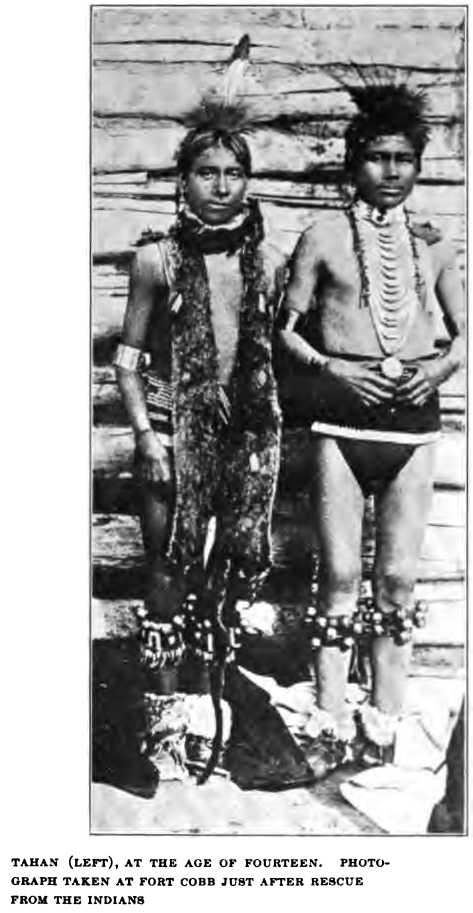

finally we reached Fort Cobb. Here we remained all winter closely

guarded by soldiers.

Spring came and my feet

were well. One day as I was playing in the warm sunshine, two white men

came along and looked at me fiercely. One of them grabbed me by the arm.

Wolf-like I snapped my teeth upon his hand, and bit and scratched with

all of my might, until with an exclamation he gave me a slap and let me

go. I ran into the brush and hid until darkness fell, then crept to

Mother and told her what had happened. She cautioned me to keep away

from the white men. They would either kill me or steal me, she said.

Instead, they caught me

one day, took me to an officer’s tent and brought Mother there. After a

long talk between the Indians and the officers, I learned that I was to

be taken away among the white people, for it was felt certain I was a

captive. Finally they found Indians who told of the Kiowa raid and of

the death of my own mother. From their description of our cabin and its

location, an old scout identified me. Then I was told that, within a few

days, I would be handed over to my own father—California Joe.

I did not know my father.

I did not want to go. I could not find my foster-father, Zepkhoeete. I

seemed to belong nowhere, to nobody. I wanted to creep away like a

wounded coyote, and die.

When I again saw my

foster-father, I was no longer a child; and never, since the day they

took me from her, have I seen my good foster-mother who sacrificed so

much for me.

At the ranch to which

they took me, I soon grew heartsick for the camp. It was with great

difficulty that they could make me understand them when they talked to

me, and I could not make them understand me.

I slept out by the

corral. One night the call of the camp was too strong. I mounted a good

horse and hit the trail leading northward.

On the second day I fell

in with a number of Indians returning from a raid with several good

horses and other booty. They were the most peculiar looking lot I had

ever seen. They called themselves Estizeddelebe—Brave, Dangerous People.

At first they did not

seem inclined to allow me to stay with them, but one of the young

warriors whose language I did not understand took my part. As I was not

particular where I went, so long as I did not have to return to the

white people, I accompanied my new friends to their camp. It was at the

foot of some big mountains.

A glad surprise awaited

me there. I found the parents of Nacoomee and Nacoomee herself—the

little playmate of my childhood days. |