|

Increase of Wood-Pigeons and other Birds — Service to the Farmer of

these Birds — Tame Wood —Pigeons: Food of — The Turtle-Dove — Blue

Rock-Pigeons — Caves where they Breed — Shooting at the Rocks near

Cromarty.

Owing to the decrease of

vermin, that is, of all the carnivorous birds and beasts of the country,

there is a proportionate increase in the numbers of the different living

creatures on which they preyed. I do not here allude to game only, but to

all the other ferae naturae of the district. Wood-pigeons, blackbirds,

thrushes and all the smaller birds increase yearly in consequence of the

destruction of their natural enemies. The wood-pigeon in particular has

multiplied to a great extent. The farmers complain constantly to me of the

mischief done by these birds, whom I cannot defend by giving them the

credit of atoning for their consumption of corn by an equal or greater

consumption of grubs and other noxious insects, as they feed wholly on

seeds and vegetables. An agricultural friend of mine near this place, who

had yielded with a tolerably good grace to my arguments in favour of the

rook, pointed out to me the other day (March 6th) an immense flock of

wood-pigeons busily at work on a field of young clover, which had been

under barley the last season. "There," he said, "you constantly say that

every bird does more good than harm; what good are those birds doing to my

young clover?" On this, in furtherance of my favourite axiom, that, every

wild animal is of some service to us, I determined to shoot some of the

wood-pigeons, that I might see what they actually were feeding on; for I

did not at all fall into my friend's idea that they were grazing on his

clover. By watching in their line of flight from the field to the woods,

and sending a man round to drive them off the clover, I managed to kill

eight of the birds as they flew over my head. I took them to his house,

and we opened their crops to see what they contained. Every pigeon's crop

was as full as it could possibly be of the seeds of two of the worst weeds

in the country, the wild mustard and the ragweed, which they had found

remaining on the surface of the ground, these plants ripening and dropping

their seeds before the corn is cut. Now no amount of human labour and

search could have collected on the same ground, at that time of the year,

as much of these seeds as was consumed by each of these five or six

hundred wood-pigeons daily for two or three weeks together. Indeed, during

the whole of the summer and spring, and a considerable part of the winter,

all pigeons must feed entirely on the seeds of different wild plants, as

no grain is to be obtained by these soft-billed birds excepting

immediately after the sowing-time and when the corn is nearly ripe, or for

a short time after it is cut. Certainly I can enter into the feelings of a

farmer who sees a flock of hundreds of these birds alighting on a field of

standing wheat or devouring the newly sown oats. Seeing them so employed

must for the moment make him forget the utility they are of at other

times. For my own part I never shoot at a wood-pigeon near my house, nor

do I ever kill one without a feeling of regret, so much do I like to here

their note in the spring and summer mornings. The first decisive symptom

of the approach of spring and fine weather is the cooing of the

wood-pigeon. Where not molested, they are very fond of building their nest

in the immediate vicinity of a house. Shy as they are at all other times

of the year, no bird sits closer on her eggs or breeds nearer to the abode

of man than the wood-pigeon. There are always several nests close to my

windows, and frequently immediately over some walk, where the birds sit in

conscious security, within five or six feet of the passer-by, and there

are generally a pair or two that feed with the chickens, knowing the call

of the woman who takes care of the poultry' as well as the tame birds do.

I have frequently attempted

to tame young wood pigeons, taking them at a very early age from the nest.

They generally become tolerably familiar till the first moult; but as soon

as they acquire strength of plumage and wing, they have invariably left

me, except in one instance which occurred two years ago. I put some

wood-pigeon's eggs under a tame pigeoen of my children's, taking away the

eggs on which she was sitting at the time. Only one of the young birds

grew up, and it became perfectly tame. It remained with its foster

parents, flying in and out of their house, and coming with them to be fed

at the windows. After it had grown up, and the cares of a new nest made

the old birds drive it out of their company, the wood-pigeon became still

tamer, always coming at breakfast-time or whenever he was called to the

window-sill, where he would remain as long as he was noticed, cooing and

strutting up and down as if to challenge attention to his beautiful

plumage.

However, like all pets,

this poor bird came to an untimely end, being struck down and killed by a

hen-harrier. I never on any other occasion saw a wood-pigeon remain

perfectly tame if left at liberty ; and if they are entirely confined they

seldom acquire their full beauty of feather. The bird seems to have a

natural shyness and wildness which prevent its ever becoming domesticated

like the common blue rock-pigeon.

It is very difficult to

approach wood-pigeons when feeding in the fields. They keep in the most

open and exposed places, and allow no enemy to come near them. It is

amusing to watch a large flock of these birds while searching the ground

for grain. They walk in a compact body, and in order that all may fare

alike, the hindmost rank every now and then fly over the heads of their

companions to the front, where they keep the best place for a minute or

two, till those now in the rear take their place in the same manner. They

keep up this kind of fair play during the whole time of feeding. Almost

every kind of seed is eaten by them, and the farmers accuse them of

destroying their turnips in severe snow and frost. They feed also on fruit

of all kinds, both the wild berries, such as mountain-ash, ivy, etc., and

also upon almost all garden fruits that are not too large to be swallowed.

Numbers of them come every evening to my cherry-trees, where they

fearlessly swallow as many cherries as they can hold, although the

gardener may be at work close at hand. Strawberries also are occasionally

laid waste by them; and in the winter and early spring they devour the

young cabbage and lettuce-plants. Where acorns are plentiful, the

wood-pigeons seem to prefer them to anything else ; and the quantity they

manage to stow away in their crop is perfectly astonishing.

There are many months of

the year, however, during which they are compelled, nolens volens,

to feed wholly on the seeds of wild plants, thereby saving the farmers an

infinity of trouble in weeding and cleaning their lands. The wood-pigeons

breed here great numbers, the large fir-woods and ivy-covered banks of the

river affording them plenty of shelter. Their greatest enemy in the

breeding-season is the hooded crow, who is constantly searching for their

eggs, and from their white colour, and the simplicity of the nest, he can

distinguish them at a great distance off. The sparrowhawk, too, frequently

carries off the young birds, when nearly ready to fly, taking them out of

the nest. It is a curious fact, but one I have very often observed, that

this hawk, though I have seen him in the vicinity of the wood-pigeon's

nest, and have no doubt that he has known of the young birds in it, never

carries them off till they have attained to a good size, watching their

daily growth till he thinks them fit to be killed.

In game-preserves

wood-pigeons are certainly of some use, both in affording to vermin a more

conspicuous and more favourite food than even partridge or pheasant, and

in taking the attention of the larger hawks from the game. But he also

does good service in giving notice of the approach of any danger, loudly

flapping his wings as he flies off the trees on the first alarm. And at

night no bird is so watchful. I have frequently attempted to approach the

trees where the wood-pigeons were roosting ; but even in the darkest

nights these birds would take the alarm, affording in this respect a great

contrast to the pheasant. The poor wood-pigeon has no defence against its

enemies excepting its watchful and never-sleeping timidity, not being able

to do battle against even the smallest of its numerous persecutors.

Though the turtle-dove

never breeds here, and is supposed never to visit this part of the

country, I have twice seen a pair about my house, both times towards the

end of autumn. Last year a pair remained for about three weeks here, from

the middle of October to the beginning of November, when they disappeared,

probably returning southwards, not being nearly so hardy a bird as the

wood-pigeon. Besides the wood-pigeon, we have considerable numbers of the

little blue rock-pigeon breeding along the caves and rocks of the coast,

and feeding inland in large flocks. On the opposite coast of Ross-shire

and Cromarty, very great numbers are found during the whole year. The

caves there are much more extensive, and the rocks less easy of access,

than they are along our coast by Burghead, Gordonston, etc.; the

rock-pigeons therefore make those rocks their head-quarters.

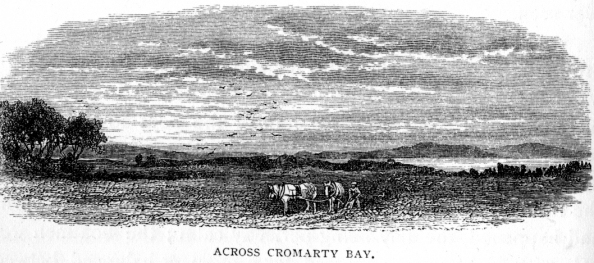

Being at Cromarty early in

last June, I made an excursion along the rocks, for the double purpose of

seeing the coast, which is peculiarly bold and magnificent on the

Ross-shire side of the Cromarty Ferry, and also of shooting some pigeons

and other birds which bred in the caves and cliffs.

Having hired a boat and

crew, we started from Cromarty at the first of the ebb on a bright calm

day, with the little wind that there was coming from the west. If the

slightest east wind comes on, the roll of the sea from the German Ocean is

so heavy on these rocks that it is impossible to approach them. This is

also the case for some days after an east wind has been blowing, as there

still remains a considerable swell. On nearing the west end of the rocks,

which are several hundred feet high, we disturbed a good many cormorants,

who were resting on some points of the cliff, and basking with open wings

in the morning sun. Some parts of the rocks were quite white with the dung

of these birds. In the ivy-covered recesses, far up, were every here and

there a pair of small hawks, and rabbits hopping about high over our

heads, along narrow paths on the face of the rock. I shot a rabbit at a

great height with a rifle, and he came tumbling over and over, till he

finally fell right into a hawk's nest, to the great astonishment of the

young birds. Innumerable jackdaws breed in every crevice. As we rowed

farther on, we came opposite a large cave, which the boatmen told me was a

great place of resort for the pigeons. So, stopping our course, the men

shouted, and out came a large flock of these birds, flying directly over

our heads. I killed two or three, and the rest flew on, winding round the

angles and headlands of the coast with inconceivable rapidity. Having

picked up the birds, I landed with great difficulty on the rocks, and

making my way over the slippery seaweed, got into the cave, which extended

some distance under the cliffs. There were several pigeons' nests, though

none that I could get at; but I shot a couple of young ones that had left

the nest. The reverberation that succeeded the report of the gun in the

arched cave nearly deafened me.

Soon afterwards we landed

at another point ; and here, following the example of one of my crew, I

crept through a small aperture on my hands and knees, which led into a

large and nearly dark cave, said to be the abode of otters. Before I could

set fire to some dry fir-roots, which we brought with us, my dog was

barking furiously, some distance within the cave. We got our light and

went to examine what he had. By the tracks, he had evidently come on an

otter, who had made his escape into a small hole which seemed to go into

the very heart of the rocks, and from which we had no chance of extracting

him. This cave was too damp for the birds, but was much marked with the

footsteps of otters. Though the entry was so small, the cave itself was

both lofty and extensive.

As we floated along the

coast, stopping at the mouths of several caves, and occasionally landing,

we put up several large flocks of pigeons, and here and there cormorants

and other sea-birds. On one shelf of the rocks, far up above the sea, was

the nest of the raven. It was once inhabited by a pair of eagles, but is

now quietly tenanted by the raven. These birds had flown; but both young

and old were flying about the tops of the cliff, croaking and playing

fantastic antics, as if in great astonishment at our appearance ; for I

fancy that they have very few visitants here. I tried a shot at one with a

rifle-ball, but only splintered the rock at his feet.

Some of the caves were of

great extent, and very full of pigeons, old and young, several of which I

killed. The birds were nearly blue; here and there a sandy-coloured one,

but no other variety. Having made our way a considerable distance along

the coast, and the tide being now quite out, we landed on a green pot of

grass that stretched down between the rocks to the water's edge. Above our

heads, and in every direction, were heron-nests; some built in the

clusters of ivy, and others on the bare shelves of rocks. The young ones

were full grown, but still in the nests standing upright and looking

gravely at us. Though I thought it a shame to make any of them orphans, I

took the opportunity of killing three fine old male herons, whose black

feathers I coveted much for my salmon-flies; sitting quietly at the foot

of the rocks, I could distinctly see which birds were well supplied with

these feathers as they flew in to feed their young over my head. The

feathers that are so useful in fly-dressing are the black drooping

feathers on the breast of the cock heron : neither the young bird nor the

hen bird has them. While resting my men here, I sent rifle-balls through

three of the herons, each of whom afforded me a goodly supply of feathers.

Looking with my glass to

the opposite coast of the firth, I could distinctly see the long range of

sandhills between Nairn and the Bay of Findhorn, and could distinguish

many familiar points and nooks. While resting here, too, a large seal

appeared not above a hundred and fifty yards out at sea, watching us with

great attention, but would not come within sure range of my rifle. As we

returned homewards, the pigeons were in great numbers flying in to the

caves to feed their young. A pair of peregrine falcons also passed along,

on their way to a rock where they breed, farther eastwards than we had

been.

We saw too a flock of goats

winding along the most inaccessible-looking parts of the cliff; and now

and then the old patriarchal-looking leader would stop to peer at us as we

passed below him, and when he saw that we had no hostile intention towards

his flock, he led them on again, stopping here and there to nibble at the

scanty herbage that was to be found in the clefts of the rocks. In one

place where we landed, my dog started an old goat and a pair of kids, who

dashed immediately at what appeared to be a perpendicular face of rock,

but on which they contrived to keep their footing in a way that quite

puzzled me. The old goat at one time alighted on a point of the rock where

she had to stand with her four feet on a spot not bigger than my hand

where she stood for a minute or two seemingly quite at a loss which way to

go, till her eye caught some (to me invisible) projections of the stone,

up which she bounded, looking anxiously at her young, who, however, seemed

quite capable of following her footsteps wherever she chose to lead them.

We caught sight also of a badger, as he scuffled along a shelf of rock and

hurried into his hole.

As the evening advanced,

the cormorants kept coming in to their roosting-places in great numbers,

and I shot several of them. We saw a good many seals as we approached the

stake-nets near the ferry, but did not get any shots at them; and at one

place two otters were playing about in the water near the rocks, but they

also took good care to disappear before we came within reach of them ; and

as I wished to get back to Cromarty before it was late, I would not stop

to wait for their reappearance. I was much pleased on the whole with my

day's excursion—the beautiful scenery of the rocks, with the harbour of

Cromarty, and the distant hills of Ross-shire and Inverness-shire, forming

altogether as magnificent and varied a view as I have ever seen.

On an excursion along these

same rocks I was once nearly drowned. I had just killed a pigeon that had

dropped in the water in a recess between the rocks. We rowed in after it,

and just as I was leaning over the bow of the boat to pick it up, a

rolling swell of the sea lifted the boat nearly upright, grating her keel

on the edge of the rock. I was hoisted with the bow of the boat into the

air, and holding on looked round to see what had happened, the day being

perfectly calm ; the boatmen were pale with fright as we appeared for a

moment balanced between life and death, the chances rather in favour of

the latter. The same wave, however, as it receded, took us twenty or

thirty yards out to sea, and the men immediately rowed as hard as they

could to get a good offing. The wave that had so nearly upset us was the

forerunner of a heavy swell and wind from the east which was coming on

unobserved by us, for we had been wholly intent on our sport. I never

could understand how our boat could have righted again after the position

she was in for a few moments. The face of the rocks was too perpendicular

at the place to admit of our making good a landing had we been upset. Once

away from the rocks we were safe enough, and rigging out a couple of

strong lines with large white flies, we caught as many fish of different

kinds as we could pull in during our way over to Cromarty. A large gull

made two swoops at one of the flies, and had not a fish forestalled him,

we should probably have hooked him also. I do not know a day's sport more

amusing than one along these rocks on a fine summer day, what with the

variety of birds and the beauty and grandeur of the scenery, taking good

care, however, to avoid the rocks when there is the least wind or swell

from the east or north.

|