|

Grouse's Nest — Partridge Nest — Grouse-shooting — Marten Cat — Witch:

Death of — Stags—Snaring Grouse — Black Game: Battles of — Hybrid Bird —

Ptarmigan-shooting — Mist on the Mountain — Stag Unsuccessful Stalking —

Death of Eagle.

I FOUND the nest of a grouse with eight eggs,

or rather eggshells, within two hundred yards of a small farm-house on a

part of my shooting ground, where there is a mere strip of heather

surrounded by cultivated fields, and on a spot particularly infested by

colley-dogs, as well as by herd-boys, et id genus omne. But

the poor bird, although so surrounded by enemies, had managed to hatch and

lead away her brood in safety. I saw them frequently afterwards, and they

all came to maturity. How many survived the shooting-season I do not know,

but the covey numbered eight birds far on in October. If the parent bird

had selected her nesting-place for beauty of prospect, she could not have

pitched upon a lovelier spot. The nest was on a little mound where I

always stop, when walking in that direction, to admire the extensive and

varied view—the Bay of Findhorn and the sand-hills, the Moray Firth, with

the entrance to the Cromarty Bay, and the bold rocky headlands, backed by

the mountains of Ross-shire. Sutherland, Caithness, Inverness, and

Ross-shire are all seen from this spot; whilst the rich plains of Moray,

dotted with timber, and intersected by the winding stream of the Findhorn,

with the woods of Altyre, Darnaway, and Brodie, form a nearer picture.

It is a curious fact, but one which I have

often observed, that dogs frequently pass close to the nest of grouse,

partridge, or other game, without scenting the hen bird as she sits on her

eggs. I knew this year of a partridge's nest which was placed close to a

narrow footpath near my house; and although not only my people, but all my

dogs, were constantly passing within a foot and a half of the bird, they

never found her out, and she hatched her brood in safety.

Grouse generally make their nest in a high

tuft of heather. The eggs are peculiarly beautiful and game-like, of a

rich brown colour, spotted closely with black. Although in some peculiarly

early seasons the young birds are full grown by the 12th of August, in

general five birds out of six which are killed on that day are only half

come to their strength and beauty. The loth of the month would be a much

better day on which to commence their legal persecution. In October there

is not a more beautiful bird in our island; and in January a cock grouse

is one of the most superb fellows in the world, as he struts about

fearlessly with his mate, his bright red comb erected above his eyes, and

his rich dark-brown plumage shining in the sun. Unluckily, they are more

easily killed at this time of the year than at any other; and I have been

assured that a ready market is found for them not only in January, but to

the end of February, though in fine seasons they begin to nest very early

in March. Hardy must the grouse be, and prolific beyond calculation, to

supply the numbers that are yearly killed, legally and illegally. Vermin,

however, are their worst enemies; and where the ground is kept clear of

all their winged and four-footed destroyers, no shooting seems to reduce

their numbers.

I cannot say that my taste leads me to rejoice

in the slaughter of a large bag of grouse in one day. I have no ambition

to see my name in the county newspapers as having bagged my seventy brace

of grouse, in a certain number of hours, on such and such a hill. I have

much more satisfaction in killing a moderate quantity of birds, in a wild

and varied range of hill, with my single brace of dogs, and wandering in

any direction that fancy leads me, than in having my day's beat laid out

for me, with relays of dogs and keepers, and all the means of killing the

grouse on easy walking ground, where they are so numerous that one has

only to load and fire. In the latter case, I generally find myself

straying off in pursuit of some teal or snipe, to the neglect of the

grouse and the disgust of the keeper, who may think his dignity

compromised by attending a sportsman who returns with less than fifty

brace. Nothing is so easy to shoot as a grouse, when they are tolerably

tame; and, with a little choice of his shots, a very moderate marksman

ought to kill nearly every bird that he shoots at early in the season,

when the birds sit close, fly slowly, and are easily found. At the end of

the season, when the coveys are scattered far and wide, and the grouse

rise and fly wildly, it requires quick shooting and good walking to make

up a handsome bag; but how much better worth killing are the birds at this

time of year than in August ! If my reader will wade through some leaves

of an old note-book, I will describe the kind of shooting that, in my

opinion, renders the sporting in the Highlands far preferable to any other

that Great Britain can afford.

October 20th.—Determined to shoot across to Malcolm's shealing, at the

head of the river, twelve miles distant; to sleep there; and kill some

ptarmigan the next day.

For the first mile of our walk we passed

through the old fir woods, where the sun seldom penetrates. In the

different grassy glades we saw several roe, but none within shot. A

fir-cone falling to the ground made me look up, and I saw a marten cat

running like a squirrel from branch to branch. The moment the little

animal saw that my eye was on him he stopped short, and curling himself up

in the fork of a branch, peered down on me. Pretty as he was I fired at

him. He sprang from his hiding-place, and fell half way down, but catching

at a branch, clung to it for a minute, holding on with his fore-paws. I

was just going to fire at him again, when he lost his hold, and came down

on my dogs' heads, who soon despatched him, wounded as he was. One of the

dogs had /earned by some means to be an excellent vermin-killer, though

steady and staunch at game. As we were just leaving the wood a woodcock

rose, which I killed. Our way took us up the rushy course of a burn. Both

dogs came to a dead point near the stream, and then drew for at least a

quarter of a mile, and just as my patience began to be exhausted, a brace

of magnificent old blackcocks rose, but out of shot. One of them came back

right over our heads at a good height, making for the wood. As he flew

quick down the wind, I aimed nearly a yard ahead of him as he came towards

me, and down he fell, fifty yards behind me, with a force that seemed

enough to break every bone in his body. Another and another blackcock fell

to my gun before we had left the burn, and also a hare, who got up in the

broken ground near the water. Our next cast took us up a slope of hill,

where we found a wild covey of grouse. Right and left at them the moment

they rose, and killed a brace the rest went over the hill. Another covey

on the same ground gave me three shots. From the top of the hill we saw a

dreary expanse of flat ground, with Loch A-na-caillach in the centre of

it, a bleak cold-looking piece of water, with several small grey pools

near it. Donald told me a long story of the origin of its name, pointing

out a large cairn of stones at one end of it. The story was, that some few

years ago—" Not so long either, Sir (said Donald); for Rory Beg, the auld

smuggler, that died last year, has often told me that he minded the whole

thing weel "—there lived down below the woods an old woman, by habit and

repute a witch, and one possessed of more than mortal power, which she

used in a most malicious manner, spreading sickness and death among man

and beast. The minister of the place, who came, however, but once a month

to do duty in a building called a chapel, was the only person who, by dint

of prayer and Bible, could annoy or resist her. He at last made her so

uncomfortable by attacking her with holy water and other spiritual

weapons, that she suddenly left the place, and no one knew where she went

to. It soon became evident, however, that her abode was not far off, as

cattle and people were still taken ill in the same unaccountable manner as

before. At last, an idle fellow, who was out poaching deer near Loch A-na-caillach

late one evening saw her start through the air from the cairn of stones

towards the inhabited part of the country. This put people on the lookout,

and she was constantly seen passing to and fro on her unholy errands

during the fine moonlight nights. Many a time was she shot at as she flew

past, but without success. At last a pot-valiant and unbelieving old

fellow, who had long been a serjeant in some Highland regiment, determined

to free his neighbours from the witch; and having loaded his gun with a

double charge of gunpowder, put in, instead of shot, a crooked sixpence

and some silver buttons, which he had made booty of somewhere or other in

war time. He then, in the most foolhardy manner, laid himself down on the

hill, just where we were then standing when Donald told .me the story,

and, by the light of the moon, watched the witch leave her habitation in

the cairn of stones. As soon as she was gone, he went to the very place

which she had just left, and there lay down in ambush to await her return.

"'Deed did he, Sir; for auld Duncan was a mad-like deevil of a fellow, and

was feared of nothing." Long he waited, and many a pull he took at his

bottle of smuggled whisky, in order to keep out the cold of a September

night. At last, when the first grey of the morning began to appear, "

Duncan hears a sough, and a wild uncanny kind of skirl over his head, and

he sees the witch hersel, just coming like a muckle bird right towards

him,—'deed, Sir, but he wished himsel at hame; and his finger was so stiff

with cold and fear that he could na scarce pull the trigger. At last, and

long, he did put out (Anglic, shoot off) just as she was hovering over his

head, and going to light down on the cairn." Well, to cut the story short,

the next morning Duncan was found lying on the cairn in a deep slumber,

half sleep and half swoon, with his gun burst, his collar-bone nearly

broken, and a fine large heron shot through and through lying beside him,

which heron, as every one felt assured, was the caillach herself. "She has

na done much harm since yon (concluded Donald); but her ghaist is still to

the fore, and the loch side is no canny after the gloaming. But, Lord

guide us, Sir, what's that ?" and a large long-legged hind rose from some

hollow close to the loch, and having stood for a minute with her long ears

standing erect, and her gaze turned intently on us, she trotted slowly

off, soon disappearing amongst the broken ground. But where are the dogs

all this time ? There they are, both standing, and evidently at different

packs of grouse. I killed three of these birds, taking a right and left

shot at one dog's point, and then going to the other.

Off went Old Shot now, according to his usual

habit, straight to a rushy pool. I had him from a friend in Ireland, and

being used to snipe-shooting, he preferred it to everything else. The

cunning old fellow chose not to hear my call, but made for his favourite

spot. He immediately stood, and now for the first time seemed to think of

his master, as he looked back over his shoulder at me, as much as to say,

" Make haste down to me, here is some game." And sure enough up got a

snipe, which I killed. The report of my gun putting up a pair of mallards,

one of which I winged a long way off, "Hie away, Shot," and Shot, who was

licensed to take such liberties, splashed in with great glee, and after

being lost to sight for some minutes amongst the high rushes, came back

with the mallard in his mouth. " A bad lesson for Carlo that, Master

Shot," but he knows better than to follow your example. We now went up the

opposite slope, leaving Loch A-na-caillach behind us, and killing some

grouse, and a mountain hare, with no white about her as yet. We next came

to a long stony ridge, with small patches of high heather. A pair of

ravens, rising from the rocks, soared croaking over us for some time. A

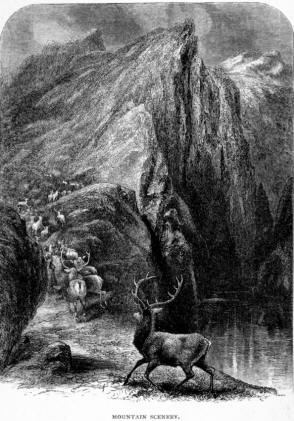

pair or two of old grouse were all we killed here. But the view from the

summit was splendidly wild as we looked over a long range of grey rocks,

beyond which lay a wide and extensive lake, with several small islands in

it. The opposite shore of the lake was fringed with birch-trees, and in

the distance were a line of lofty mountains whose sharp peaks were covered

with snow. Human habitation or evidence of the presence of man was there

not, and no sound broke the silence of the solitude excepting the croak of

the ravens and the occasional whistle of a plover. "Yon is a fine corrie

for deer," said Donald, making me start, as he broke my reverie, and

pointing out a fine amphitheatre of rocks just below us. Not being on the

look-out for deer, however, I did not pay much attention to what he said,

but allowed the dogs to range on where they liked. Left to themselves, and

not finding much game, they hunted wide, and we had been walking in

silence for some time, when on coming round a small rise between us and

the dogs, I saw two fine stags standing, who, intent on watching the dogs,

did not see us. After standing motionless for a minute, the deer walked

deliberately towards us, not observing us until they were within forty

yards; they then suddenly halted, stared at us, snorted, and then went off

at a trot, but soon breaking into a gallop, fled rapidly away, but were in

sight for a long distance. Shot stood watching the deer for some time, but

at last seeing that we took no steps against them, looked at me, and then

went on hunting. We killed several more grouse and a brace of teal.

Towards the afternoon we struck off to the shepherd's house. In the fringe

of a birch that sheltered it we killed a blackcock and hen, and at last

got to the end of our walk with fifteen brace of grouse, five black game,

one mallard, a snipe, a woodcock, two teal, and two hares; and right glad

was I to ease my shoulder of that portion of the game which I carried to

help Donald, who would at any time have preferred assisting me to stalk a

red deer than to kill and carry grouse. Although my day's sport did not

amount to any great number, the variety of game, and the beautiful and

wild scenery I had passed through, made me enjoy it more than if I had

been shooting in the best and easiest muir in Scotland, and killing fifty

or sixty brace of birds.

In preserving and increasing a stock of

grouse, the first thing is to kill the vermin of every kind, and none more

carefully than the grey crows, as these keen-sighted birds destroy an

immense number of eggs. The grouse should also be well watched in the

neighbourhood of any small farms or corn-fields that may be on the ground,

as incredible numbers are caught in horsehair snares on the sheaves of

corn. A system of netting grouse has been practised by some of the

poachers lately, and when the birds are not wild they catch great numbers

in this manner; and as in nine cases out of ten the shepherds are in the

habit of assisting and harbouring the poachers, as well as allowing their

dogs to destroy as many eggs and young birds as they like, these men

require as much watching as possible. I have generally found it entirely

useless to believe a word that they tell me respecting the encroachments

of poachers, even if they do not poach themselves. With a clever sheep-dog

and a stick I would engage to kill three parts of every covey of young

grouse which I found in July and the first part of August; and, in fact,

the shepherds generally do kill great numbers in this noiseless and

destructive manner. As the black game for the most part breed in

plantations, where sheep and shepherds have no business to be found, they

are less likely to be killed in this way. But the young ones, till nearly

full grown, lie so close, that it is quite easy to catch half the brood.

When able to run, the old hen leads them to

the vicinity of some wet and mossy place in or near the woodlands, where

the seeds of the coarse grass and of other plants, and the insects that

abound near the water, afford the young birds plenty of food. The hen

takes great care of her young, fluttering near any intruder as if lame,

and having led him to some distance from the brood takes flight, and

making a circuit returns to them. The cock bird sometimes keeps with the

brood, but takes good care of himself, and running off leaves them to

their fate. Wild and wary as the blackcock usually is, he sometimes waits

till you almost tread on him, and then flutters away, giving as easy a

shot to the sportsman as a turkey would do. At other times, being fond of

basking in the sun, he lies all day enjoying its rays in some open place

where it is difficult to approach him without being seen.

In snowy weather the black game perch very

much on the fir-trees, as if to avoid chilling their feet on the colder

ground : in wet weather they do the same.

During the spring, and also in the autumn,

about the time the first hoar-frosts are felt, I have often watched the

blackcocks in the early morning, when they collect on some rock or height,

and strut and crow with their curious note not unlike that of a

wood-pigeon. On these occasions they often have most desperate battles. I

have seen five or six blackcocks all fighting at once, and so intent and

eager were they, that I approached within a few yards before they rose.

Usually there seems to be a master-bird in these assemblages, who takes up

his position on the most elevated spot, crowing and strutting round and

round with spread-out tail like a turkey-cock, and his wings trailing on

the ground. The hens remain quietly near him, whilst the smaller or

younger male birds keep at a respectful distance, neither daring to crow,

except in a subdued kind of voice, or to approach the hens. If they

attempt the latter, the master-bird dashes at the intruder, and often a

short melee ensues, several others joining in it, but they soon return to

their former respectful distance. I have also seen an old blackcock

crowing on a birch-tree with a dozen hens below it, and the younger cocks

looking on in fear and admiration. It is at these times that numbers fall

to the share of the poacher, who knows that the birds resort to the same

spot every morning.

Strong as the blackcock is, he is often killed

by the peregrine falcon and the hen-harrier. When pursued by these birds,

I have known the blackcock so frightened as to allow himself to be taken

by the hand. I once caught one myself who had been driven by a falcon into

the garden, where he took refuge under a gooseberry bush and remained

quiet till I picked him up. I kept him for a day or two, and then, as he

did not get reconciled to his prison, I turned him loose to try his

fortune again in the woods. Like some other wary birds, the blackcock,

when flushed at a distance, if you happen to be in his line of flight,

will pass over your head without turning off, as long as you remain

motionless. In some places, apparently well adapted for these birds, they

will never increase, although left undisturbed and protected, some cause

or other preventing their breeding. Where they take well to a place, they

increase very rapidly, and, from their habit of taking long flights, soon

find out the cornfields, and are very destructive, more so, probably, than

any other kind of winged game. A bold bird by nature, the black-cock, when

in confinement, is easily tamed, and soon becomes familiar and attached to

his master. In the woods instances are known of the blackcock breeding

with the pheasant. I saw a hybrid of this kind at a bird-stuffer's in

Newcastle : it had been killed near Alnwick Castle. The bird was of a

beautiful bronzed-brown colour, and partaking in a remarkable degree of

the characteristics of both pheasant and black game. I have heard also of

a bird being killed which was supposed to be bred between grouse and black

game, but I was by no means satisfied that it was anything but a

peculiarly dark-coloured grouse. The difference of colour in grouse is

very great, and on different ranges of hills is quite conspicuous. On some

ranges the birds have a good deal of white on their breasts, on others

they are nearly black : they also vary very much in size. Our other

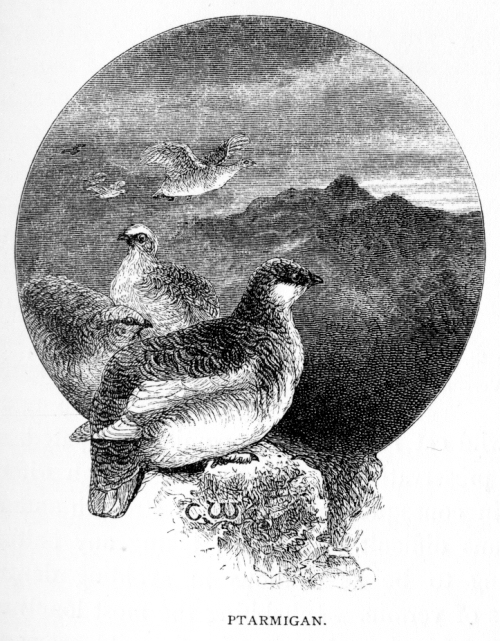

species of grouse, the ptarmigan, as every sportsman knows, is found only

on the highest ranges of the Highlands. Living above all vegetation, this

bird finds its scanty food amongst the loose stones and rocks that cover

the summits of Ben Nevis and some other mountains. It is difficult to

ascertain indeed what food the ptarmigan can find in sufficient quantities

on the barren heights where they are found. Being visited by the sportsman

but rarely, these birds are seldom at all shy or wild, but, if the day is

fine, will come out from among the scattered stones, uttering their

peculiar croaking cry, and running in flocks near the intruder on their

lonely domain, offer, even to the worst shot, an easy chance of filling

his bag. When the weather is windy and rainy, the ptarmigan are frequently

shy and wild; and when disturbed, instead of running about like tame

chickens, they fly rapidly off to some distance, either round some

shoulder of the mountain, or by crossing some precipitous and rocky ravine

get quite out of reach. The shooting these birds should only be attempted

on fine calm days. The labour of reaching the ground they inhabit is

great, and it often requires a firm foot and steady head to keep the

sportsman out of danger after he has got to the rocky and stony summit of

the mountain. In deer-stalking I have sometimes come amongst large flocks

of ptarmigan, which have run croaking close to me, apparently conscious

that my pursuit of nobler game would prevent my firing at them. Once, on

one of the highest mountains of Scotland, a cold, wet mist suddenly came

on. We heard the ptarmigan near us in all directions, but could see

nothing at a greater distance than five or six yards. We were obliged to

sit down and wait for the mist to clear away, as we found ourselves

gradually getting entangled amongst loose rocks, which frequently, on the

slightest touch, rolled away from under our feet, and we heard them

dashing and bounding down the steep sides of the mountain, sometimes

appearing, from the noise they made, to be dislodging and driving before

them large quantities of debris; others seemed to bound in long leaps down

the precipices, till we lost the sound far below us in the depths of the

corries. Not knowing our way in the least, we agreed to come to a halt for

a short time, in hopes of some alteration in the weather. Presently a

change came over the appearance of the mist, which settled in large fleecy

masses below us, leaving us as it were on an island in the midst of a

snow-white sea, the blue sky and bright sun above us without a cloud. As a

light air sprang up, the mist detached itself in loose masses, and by

degrees drifted off the mountain side, affording us again a full view of

all around us. The magnificence of the scenery, looking down from some of

these mountain heights into the depths of the rugged and steep ravines

below, is often more splendid and awfully beautiful than pen or pencil can

describe; and the effect is often greatly increased by the contrast

between some peaceful and sparkling stream and green valley seen afar off,

and the rugged and barren foreground of rock and ravine, where no living

thing can find a resting-place save the eagle or raven.

I remember a particular incident of that day's

ptarmigan-shooting; which, though it stopped our sport for some hours, I

would not on any account have missed seeing. Most of the mist had cleared

away, excepting a few cloud-like drifts, which were passing along the

steep sides of the mountain. These, as one by one they gradually came into

the influence of the currents of air, were whirled and tossed about, and

then disappeared; lost to sight in the clear noonday atmosphere, as if

evaporated by wind and sun.

One of these light clouds, which we were watching, was suddenly caught in

an eddy of wind, and, after being twisted into strange fantastic shapes,

was lifted up from the face of the mountain like a curtain, leaving in its

place a magnificent stag, of a size of body and stretch of antler rarely

seen; he was not above three hundred yards from us, and standing in full

relief between us and the sky. After gazing around him, and looking like

the spirit of the mountain, he walked slowly on towards a ridge which

connected two shoulders of the mountain together. Frequently he stopped

and scratched with his hoof at some lichen-covered spot, feeding slowly

(quite unconscious of danger) on the moss which he separated from the

stones. I drew my shot and put bullets into both barrels, and we followed

him cautiously, creeping through the winding hollows of the rocks,

sometimes advancing towards the stag, and at other times obliged suddenly

to throw ourselves flat on the face of the stony mountain, to avoid his

piercing gaze, as he turned frequently round to see that no enemy was

following in his track.

He came at one time to a ridge from which he

had a clear view of a long stretch of the valley beneath. Here he halted

to look down either in search of his comrades or to see that all was safe

in that direction. I could see the tops of his horns as they remained

perfectly motionless for several minutes on the horizon. We immediately

made on for the place, crawling like worms over the stones, regardless of

bruises and cuts. We were within about eighty yards of the points of his

horns; the rest of the animal was invisible, being concealed by a mass of

stone behind which he was standing. I looked over my shoulder at Donald,

who answered my look with a most significant kind of silent chuckle; and,

pointing at his knife as if to say that we should soon require its

services, he signed to me to move a little to the right hand, to get the

animal free of the rock, which prevented my shooting at him. I rolled

myself quietly a little to one side, and then silently cocking both

barrels, rose carefully and slowly to one knee. I had already got his head

and neck within my view, and in another instant would have had his

shoulder. My finger was already on the trigger, and I was rising gradually

an inch or two higher. The next moment he would have been mine, when,

without apparent cause, he suddenly moved, disappearing from our sight in

an instant behind the rocks. I should have risen upright, and probably

should have got a shot; but Donald's hand was laid on my head without

ceremony, holding me down. He whispered, " The muckle brute has na felt

us; we shall see him again in a moment." We waited for a few minutes,

almost afraid to breathe, when Donald, with a movement of impatience,

muttered, "'Deed, Sir, but I'm no understanding it,"—and whispered to me

to go on to look over the ridge, which I did, expecting to see the stag

feeding, or lying close below it. When I did look over, however, I saw the

noble animal at a considerable distance, picking his way down the slope to

join some half-dozen hinds who were feeding below him, and who

occasionally raised their heads to take a good look at their approaching

lord and master. " The Deil tak the brute," was all that Donald said, as

he took a long and far-sounding pinch of snuff, his invariable consolation

and resource in times of difficulty or disappointment. When the stag had

joined the hinds, and some ceremonies of recognition had been gone

through, they all went quietly and steadily away, till we lost sight of

them over the shoulder of the next hill. "They'll no stop till they get to

Alt-na-cahr," said Donald, naming a winding rushy burn at some distance

off; " Alt-na-cahr " meaning the " Burn of many turns," as far as my

knowledge of Gaelic goes. And there we were constrained to leave them and

continue our ptarmigan-shooting, which we did with but little success and

less spirit. Soon afterwards a magnificent eagle suddenly rose almost at

our feet, as we came to the edge of a precipice, on a shelf of which, near

the summit, he had been resting. Bang went one barrel at him at a distance

of twenty yards. The small shot struck him severely, and, dropping his

legs, he rose into the air, darting upwards nearly perpendicularly, a

perfect cloud of feathers coming out of him. He then came wheeling in a

stupified manner back over our heads. We both of us fired together at him,

and down he fell with one wing broken, and hit all over with our small

shot. He struggled hard to keep up with the other wing, but could not do

so, and came heavily to the ground within a yard of the edge of the

precipice. He fell over on his back at first, and then rising up on his

feet, looked round with an air of reproachful defiance. The blood was

dropping slowly out of his beak, when Donald foolishly ran to secure him,

instead of leaving him to die where he was; in consequence of his doing

so, the eagle fluttered back a few steps, still, however, keeping his face

to the foe. But coming to the edge of the precipice, he fell backwards

over it, and we saw him tumbling and struggling downwards, as he strove to

cling to the projections of the rock—but in vain, as he came to no stop

till he reached the bottom, where we beheld him, after regaining his feet

for a short time, sink gradually to the ground. It was impossible for us

to reach the place where he lay dead without going so far round that the

daylight would have failed us. I must own, notwithstanding the reputed

destructiveness of the eagle, that I looked with great regret at the dead

body of the noble bird, and wished that I had not killed him, the more

especially as I was obliged to leave him to rot uselessly in that

inaccessible place.

|