|

The War in Louisiana.

That the people of

Louisiana were not overwhelmingly in favor of secession was shown by the

events of the winter of 1860-61. At the presidential election in November,

1860, the vote was: Breckinridge, 22,681; Bell, 20,204; Douglas, 7,625.

Upon learning the result of the election, Governor Moore called the

legislature in special session, and that body ordered a constitutional

convention to meet in January, 1861, at Baton Rouge. The vote for

delegates to the convention showed that the people were divided about as

follows: for immediate, separate secession, 20,448; for united action of

the South, 17,296. The convention which met January 23, passed, three days

later, an ordinance of secession by a vote of 113 to 17. The military

posts and arsenals in the state were seized and occupied, and for nearly

two months the "Republic of Louisiana" had control of all its own affairs.

On March 21 the convention ratified the Confederate Constitution and

Louisiana became one of the Confederate States. To the service of the

Confederacy the state contributed some leaders of signal ability, among

them Benjamin, Slidell, Roman and Kenner of the civilians, and Beauregard,

Polk, Bragg and Taylor of the army. And until cut off from the rest of the

Confederacy by the opening of the Mississippi, Louisiana sent more than

its quota of troops to guard the upper frontier of the South.

During the first year the

war fever ran high. All were united, it seemed, against a common foe. The

parishes made appropriations for the support and pay of their soldiers;

the city of New Orleans spent all its available funds to aid in the

mustering of troops, and all over the state private individuals made

generous contributions to aid the movement. There was for a year but

little thought of danger from invasion. True, the coast was blockaded and

the commerce of New Orleans was destroyed, but the eyes of most

Louisianians were turned to the Virginia frontier. The troops raised in

the state were rapidly sent out, and by November, 1861, 24,000 had gone,

while nearly 30,000 more were being assembled and organized.

The proper defense of

Louisiana was neglected by both the Confederate and the state governments.

Vicksburg was relied upon to hold the upper gateway of the Mississippi,

while Forts Jackson and St. Philip, on opposite sides of the Mississippi

River, seventy-five miles below New Orleans, with some batteries at

Chalmette, guarded the lower part of the state. General Lovell, with 3,000

militia, was in command at New Orleans, and a fleet of seventeen light

vessels lay on the river.

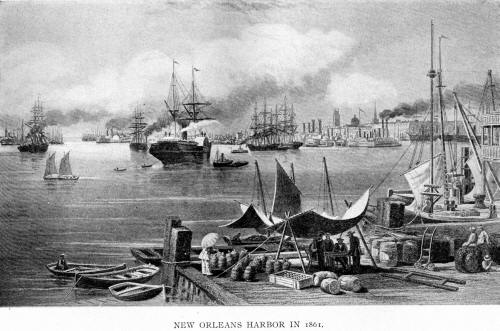

The Federals planned from

the first to open the Mississippi River, capture New Orleans, and thus cut

the Confederacy in two. New Orleans was the most important city in the

South; it controlled the lower Mississippi and it was the crossing point

for supplies from the "West; it also contained stores, factories,

shipyards and arsenals belonging to the Confederate government. The

capture of the city was planned during the winter of 1861, and in April,

1862, Admiral Farragut entered the mouth of the Mississippi with

forty-three vessels carrying 302 guns. On April 19 he appeared below Forts

Jackson and St. Philip, and began a bombardment which lasted four days.

Across the river between the forts were placed obstructions bound together

with chains, to prevent the passage of hostile vessels. Farragut sent a

gunboat to break the chain and then ran his fleet past the forts,

destroyed the weak Confederate fleet and steamed up to New Orleans.

Hearing that the Federal fleet had passed the

forts, General Lovell destroyed the government supplies which consisted of

cotton, tobacco, sugar, boats, etc., and prepared to evacuate New Orleans,

which could not be defended against a bombardment. On April 26 Farragut's

fleet appeared before the city. The river was high and his guns commanded

every part. To a demand for the surrender of the city, Monroe, the mayor,

answered that he had no military authority and hence could not comply.

Farragut threatened to bombard the city, but refrained when he learned

that the forts below had surrendered to Commodore D. D. Porter. The

transports came up with an army of 15,000 men under Gen. B. F. Butler, and

on May 1 the city was turned over to him. The loss of New Orleans was a

severe blow to the Confederacy. The place now served as a starting point

for other Federal expeditions, and it was only a matter of a short time

until the whole river would be opened.

Butler's rule of the conquered city is still

bitterly remembered. He made use of every conceivable means of humiliating

the white people left in his power. He displaced at once the local

officials and ruled by martial law. The property of Confederates was

confiscated and sold, often to the profit of Butler's friends; heavy

assessments were levied upon Confederate sympathizers; hundreds of spies

were employed to watch the more important citizens and to locate property

that had been hidden; men and women were arrested and sent to Ship Island

under negro guards one man, William B. Munford, was hanged because he

had taken down a United States flag raised in New Orleans before the

surrender. Butler disarmed the inhabitants and forced 60,000 to take the

oath of allegiance to the United States. He practically destroyed slavery

in the city by encouraging the slaves to leave their masters, by enlisting

them into the army and by issuing supplies to them. He and his brother

were interested in the contraband trade in cotton, cattle and supplies

which was carried on between New Orleans and the districts held by the

Confederates, and both made fortunes while in Louisiana. Butler became

involved in a controversy with the foreign consuls in New Orleans, from

one of whom he had taken a large amount of coin. After investigation,

President Lincoln ordered Butler to restore it.

But General Butler was, and still is, hated

most for his famous Order No. 28, which read as follows:

"As the officers and soldiers of the United

States have been subject to repeated insults from the women (calling

themselves ladies) of New Orleans, in return for the most scrupulous

non-interference and courtesy on our part, it is ordered that hereafter

when any female shall by word, gesture or movement, insult or show

contempt for any officer or soldier of the United States she shall be

regarded and held liable to be treated as a woman of the town plying her

avocation."

The order aroused

indignation not only in the South but in the North and abroad. But it is

only typical of Butler's general attitude toward the people under his

rule. Much to the relief of all he was superseded in December, 1862, by

Gen. N. P. Banks.

Butler was no general and accomplished little toward occupying other parts

of the state. Admiral Farragut went up the river, captured Baton Rouge,

the capital, bombarded and burned Bayou Sara, and ran past the batteries

of Vicksburg. The Confederates were anxious to regain Baton Rouge in order

to be able to get supplies down the Bed River and across the Mississippi.

On Aug. 5, 1862, Gen. John C. Breckinridge, with 3,000 men from Vicksburg,

attacked the Federal garrison at Baton Rouge under General "Williams. It

was expected that the ironclad Arkansas would come down from Vicksburg to

aid in the attack, but her engines gave out, and a few miles above Baton

Rouge she was fired and abandoned by her crew. Breckinridge drove the

Federals to the river under cover of their gunboats, but owing to the loss

of the Arkansas was obliged to retire. The Confederates now, in order to

secure the supplies that came down the Red River, fortified Port Hudson

above Baton Rouge.

After the fall of the state capital, Governor Moore established his

government at Opelousas and began to raise a small army. Gen. Richard

Taylor, son of Gen. Zachary Taylor, was sent from the Virginia army to

command the Confederate troops in Louisiana. He raised a small but very

good army, and during the rest of the time held the Federals in check

along the Teche and the Atchafalaya.

Hostilities in 1863 were confined to that part

of the state below Alexandria along the Red River and along the Teche.

Banks made little headway against the inferior forces of the Confederates.

In March, 1863, the Trans-Mississippi Department, embracing all of the

Confederacy west of the Mississippi, was organized, and Gen. E. Kirby

Smith was placed in command with headquarters at Shreveport, which had

been made the capital of Louisiana. Taylor acted under his command. Banks

first massed 25,000 men at Baton Rouge as if for an attack on Port Hudson,

but in April this force was transferred to the Teche country and the

Federals started for the interior of the state. Taylor, with his small

force, could only fight and fall back. There were engagements at Bisland,

Opelousas, New Iberia and Bayou Vermilion, and on May 1 the Federals

finally reached Alexandria by land and river. Taylor was then ordered to

send 4,000 men to Vicksburg, so with the remainder he fell back and ceased

operations. In June, Banks left Alexandria and carried his forces to

besiege Port Hudson, which, after withstanding the bombardments by the

fleet and repelling two assaults by the army, was surrendered on July 9.

Vicksburg had fallen on July 4, and the Mississippi was now open and the

Confederacy cut in two.

While Banks was before Port Hudson General

Taylor made use of the opportunity to drive the Federals out of southern

Louisiana. During the month of June he regained the territory almost to

New Orleans, and was planning an attack on the city when he heard of the

fall of Vicksburg and Port Hudson. During the remainder of 1863 Taylor

carried on the usual defensive campaign along the Teche. The year ended

with all of the state under Confederate control with the exception of New

Orleans, the banks of the Mississippi and the country between Berwick Bay

and New Orleans. In

1864 the Federals began a fourth campaign into the interior of the state.

Commodore Porter with seventeen vessels, and Gen. A. J. Smith with 10,000

men went up Red River; General Franklin with 18,000 men marched up the

Teche; General Steele with an army of 7,000 moved down from Arkansas upon

Shreveport. Taylor, who had been slowly falling back with 8,800 men under

Generals Mouton, Thomas, Green and Prince Polignac, stopped at Mansfield

for battle. Taylor's troops, though greatly outnumbered, were eager to

fight, and Bank's army was defeated in detail. Taylor pursued the Federals

four miles to Pleasant Hill, where the next day a drawn battle was fought

and Banks made a disorderly retreat down the Red River. Taylor wanted to

pursue Banks and destroy his army, but Kirby Smith, who feared Steele's

column which was coming down from Arkansas, diverted some of Taylor's

troops to go against Steele. Banks continued to retreat down the Red

River, laying waste the country as he went. Taylor's small forces harassed

him and cut off many of his men. On May 20 he reached the Mississippi and

the pursuit ceased. At no time had the pursuing force been one-third as

large as the Federal army. Taylor, who had not agreed with Smith as to the

conduct of the campaign, asked to be transferred east of the Mississippi;

the Federals withdrew to New Orleans and the war in Louisiana was ended.

Reconstruction During the War.

The political history of Confederate Louisiana

during the war was almost insignificant. Governor Moore, after the fall of

Baton Rouge, moved the capital first to Opelousas and then to Shreveport,

and from Shreveport he administered the government until the end of 1863.

In January, 1864, he was succeeded by Henry W. Allen who proved to be a

most successful war governor. He enlisted men, gathered and distributed

supplies, began manufactures, and above all put heart into the people.

Both governors worked in harmony with the Confederate administration,

civil and military.

The political history of that part of the state held by the Federals is

important because it illustrates the beginnings of "Reconstruction." While

under Butler's administration martial law ruled, yet there were signs of

the coming reconstruction. The port of New Orleans was opened to commerce;

slaves were practically emancipated by being enlisted into regiments or by

being allowed to leave their masters and choose employers; in September

Butler ordered all citizens to take the oath of allegiance, and proceeded

to confiscate the property of Confederates and their sympathizers. In

June, 1862, Provost Courts were established, and, in August, Gen. George

F. Shepley was made military governor. He revived three of the Civil

District Courts in the city and confined the work of the Provost Court to

criminal cases. In December Shepley ordered that an election for members

of Congress be held. B. F. Flanders was chosen to represent the first

district, and Michael Hahn the second. Only those who had taken the oath

were allowed to vote. Flanders and Hahn were allowed seats in Congress,

but their terms expired on March 4, 1863.

In December, 1862, a provisional court of

unlimited jurisdiction appointed by President Lincoln was organized in New

Orleans. Charles A. Peabody was the judge, and he and the other officials

were Northern men. Peabody also took charge of the provost courts. The

Federal circuit and district courts were opened. In April, 1863, the

Supreme Court of the state was reorganized with Peabody as chief justice.

Then followed the establishment of a criminal court, a probate court,

recorders' courts, and a few parish courts near New Orleans. Thus by the

end of 1863 the judicial system was reorganized in New Orleans, though by

the military appointment of outsiders, who were subject to military

control. Political

reconstruction was not so successful. During the Butler r้gime the

elements of a radical Republican party gathered in New Orleans and "Union

Associations" were formed. The men composing the "reconstruction" party in

New Orleans during the war were, in general, of contemptible character.

They were adventurers from the North, turncoats, and a very few genuine

unionists. The first form of organization was the Free State General

Committee which, in January, 1863, announced as its principles that the

state constitution was destroyed by the war, and that a general convention

should be held to make a new one. T. J. Durant was the leader of the most

radical section. In

June, 1863, a more conservative movement began. The radicals, led by

Durant, favored negro suffrage, and were upheld by General Shepley. Banks

wanted the mulattoes only to be given the right to vote at first, and

favored the more conservative party which maintained that the state

government was simply suspended and that it should be revived, not

reorganized, by a new constitution. Little was done in 1863 for two

reasons: first, Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation did not affect the

slaves of New Orleans and the adjoining parishes, and hence the radicals

could not use them in their scheme of voting; second, Banks was unable to

extend his lines and enlarge the territory held by the Federals. However,

Shepley registered the voters in New Orleans, and in November, 1863, the

conservative faction elected two members of Congress who were not admitted

to seats. The negroes of the city held mass-meetings and demanded

political privileges.

Economic reconstruction, like judicial

reorganization, made more progress in 1863 than political reconstruction.

Banks, like Butler, enlisted negroes into the army, but his main purpose

was to make them work on the plantations. He established a Free Labor

Bureau and gave it control over the black laborers. Written contracts were

required and wages were paid in all cases; the laborers were held strictly

to work; schools for negro children, and a Free Labor Bank were

established. Banks's plan for the negroes resulted in no financial success

for the planters, but it did keep the negroes from loafing about the city

and prevented disease and destitution.

In 1864 reconstruction began in earnest.

Lincoln's proclamation of Dec. 8, 1863, favored the plans of the more

conservative faction in New Orleans and displeased the radicals. In

January, 1864, the Free State Committee held a nomination meeting, which

split up into two factions. The majority went with the so-called moderates

and nominated Michael Hahn for governor and J. Madison Wells for

lieutenant-governor. The radicals, the "Free State" party, nominated B. F.

Flanders, and the independent conservatives nominated J. Q. Fellows, who

stood for "the rights of all, the Constitution and the Union." The vote

resulted: for Hahn, 3,625; for Fellows, 1,139; for Flanders, 1,007. Hahn

was by birth a Bavarian, and had been in Congress from Louisiana for one

month in 1862. He was inaugurated March 4, 1864, and on March 15, Lincoln

conferred upon him the powers formerly exercised by the military governor.

On March 28 an election was held in southeast Louisiana for delegates to a

constitutional convention, which met in April and drafted a new

constitution for the state. The members of the convention were not in

favor of negro suffrage, and were unwilling to grant even the limited

suffrage suggested by Lincoln in a letter to Hahn to negroes who owned

property, or who had been soldiers. However, the legislature was

authorized to extend the suffrage if it saw fit. Banks later explained

that the limited suffrage failed because of the opposition of those who

wanted all or nothing. Slavery was abolished and public education provided

for. In September, 1864, the constitution was ratified by a vote of 4,664

to 789. This was less than the 10 per centum vote desired by Lincoln, and

shows how little popular support the reconstruction had. Durant and the

extreme radicals carried on constant opposition to the Hahn

administration. Lincoln's proclamation of July 8, 1864, a sort of reply to

the Wade-Davis bill, indicated his purpose to stand by the reconstruction

establishments in Arkansas, Tennessee and Louisiana, but Congress refused

to admit the Louisiana representatives elected in September, 1864. The

legislature met in October and elected Hahn and E. King Cutler to the

United States Senate. The bitterest partisan spirit was manifested by the

governor and the legislature, and the law officers of the state were

directed to prosecute the leading Confederates under charges of perjury

and treason. Seven presidential electors were chosen by the legislature,

but their ballots, cast for Lincoln, were rejected by Congress in 1865.

Hahn, elected senator, resigned the governorship on March 4, 1865, and was

succeeded by J. Madison Wells, the lieutenant-governor.

Reconstruction Under President Johnson,

1865-1867. The

surrender of the Confederate armies east of the Mississippi did not

necessarily embarrass at once the forces of the Trans-Mississippi

Department, which could easily retire before the Federals. Some leaders

planned to continue resistance, hoping to get the aid of France; others

proposed to take the Confederate forces into Mexico and join Maximilian.

Governor Allen, convinced that there was no hope, insisted that the

Trans-Mississippi Department be surrendered. A convention of the

Confederate governors of Louisiana, Arkansas, Texas and Missouri was held

at Marshall, Texas, and advised Kirby Smith to surrender the Department,

which was done on May 26.

On June 2 Governor Allen issued a farewell

address to the people of Louisiana. He advised them to accept defeat with

good grace, take the oath of allegiance, go to work and win back

prosperity. To escape imprisonment he then went into exile and died a year

later in the City of Mexico. The whole state now came under the control of

the Federals and the Wells state government, and the reconstruction period

had really begun.

Conditions in Louisiana at the beginning of reconstruction were better

than in some other Southern states. With the exception of the Mississippi

and Red River valleys and the country south of Alexandria there had been

no wholesale devastation by the Federals, while whole regions of the state

had not been touched by them. Banks's experiments with free negro labor

had resulted in some valuable experience for Louisiana planters. The

courts and the state government, reorganized in and around New Orleans

during the war, were rapidly extended over the state. The loss of property

had been immense, and in North Louisiana there was much destitution and

resulting suffering. The negroes outside of New Orleans, freed by the

surrender, left the plantations to wander about. The canals, levees,

steamboats, railways and roads had gone to ruin. Plantations were going

back to forest. To such, conditions the Confederate soldier returned.

When President Johnson

inaugurated his work of restoration he merely continued the government he

found in Louisiana. So Governor Wells extended the system turned over to

him by Governor Hahn. The President's amnesty proclamation of May 29,

while proscribing the leaders, allowed the majority of the Confederates to

participate in the government. Throughout the summer of 1865 Wells

continued his work of reorganizing the state government. People began to

settle down to their old habits of life and work. Slowly society righted

itself and the future seemed hopeful. The relatively small number of

radical agitators was almost lost sight of after the return of the

Confederates. The

military authorities, the Freedmen's Bureau, and the President himself

treated the government of Louisiana as simply provisional, and frequently

interfered with the civil officials. No Confederate was allowed to hold

office who had not been pardoned by the President. The negroes soon came

under the absolute control of the Freedmen's Bureau. An election of state

officials and members of the legislature was held in November, 1865. Wells

was a candidate for governor and was supported by a few of the former

radicals and by most of the ex-Confederates who thought it best to elect a

governor who had no Confederate record. There was a movement in favor of

reelecting Governor Allen, then in Mexico, who wanted to return to

Louisiana, but who refused to be considered a candidate for any office. If

he had consented to be a candidate he would have been elected, but some of

the former Confederate leaders, knowing Allen's wishes, issued an address

pointing out the unwisdom of such a course, and Governor Wells, who feared

Allen as an opposing candidate, sent a lying message to him that it would

not be safe for him to return to Louisiana that Johnson was unwilling.

In the election Allen received 5,497 votes, and Wells 22,312. Albert

Voorhies, a Democrat, was chosen lieutenant-governor, and the legislature

had a large Democratic or Conservative majority. The election for members

of Congress was also held at this time, and all of those elected were

Democrats or Conservatives. The extreme radicals refused to take part in

the election, but united with the negroes and elected Henry C. Warmoth as

delegate to Congress from the "Territory of Louisiana," as they called it.

The legislature was composed of able men; it

was perhaps the ablest "Johnson" legislature that met in 1865. It ratified

the Thirteenth amendment and elected Randall Hunt and Henry Boyce to the

United States Senate in place of Hahn and Cutter, who had been refused

admission. A great majority of the whites regarded the constitution of

1864 as a fraudulent document, and the legislature recommended that it be

submitted to the people to be voted upon. The legislature ordered an

election of city officials in New Orleans which was still ruled by

military appointees. Wells, who was about to go over to the radicals,

vetoed the act, using rather violent language in regard to ante-bellum

political conditions. The act was passed over his veto, the election was

held and John T. Monroe, who had been removed in 1862 by General Butler,

was elected mayor. The military authorities refused to allow him to serve

until he was pardoned by the President.

Two parties in the state now favored a new

constitution: the extreme radicals, who, after the Confederate majority

secured control of the state government, wanted a fundamental law

disfranchising the Confederates and granting suffrage to the blacks; and

the Democrats or Conservatives, who disliked the so-called constitution of

1864, and wanted it submitted for approval or disapproval of the people. A

committee was sent to interview President Johnson, who opposed the holding

of a new convention and the matter was dropped by the conservatives. The

radicals continued to demand the exclusion of Confederates from

citizenship. As time

went on Governor Wells became more and more radical and lost the support

of those who had elected him. Lieutenant-Governor Voorhies was now looked

upon as the real head of the state administration and the representative

of the whites, and in political matters he so acted, he and "Wells

becoming rivals. The

Louisiana radicals, encouraged by the attitude of Congress and instigated

by radical leaders in Washington, now planned a political revolution for

the purpose of getting control of the state government. The convention of

1864, fearing that the constitution framed by it might not be adopted, did

not dissolve sine die, but adjourned to meet at the call of its president.

The adoption of the constitution rendered another meeting unnecessary and

terminated the existence of the convention. Now, however, the extreme

radicals called upon the former president, Judge Durell, to reconvene the

convention. He refused, and on June 26 about twenty-five of the former

members chose as chairman Judge E. K. Howell of the Supreme Court, who had

been a member of the convention of 1864, but who had resigned before the

convention adjourned. He accepted the position and issued a call for the

convention of 1864 to reassemble on July 30, 1866, and asked Governor

Wells to hold an election to fill vacancies. The latter did so, but named

September 3 as the day for the election.

The radicals, now led by ex-Governor Hahn, met

July 27 and agreed not to wait for the elections, but to hold the

convention on July 30 as first planned. Violent speeches were made for the

purpose of rousing the negroes, who, in great numbers, flocked to the

meeting. Dr. A. P. Dostie declared that the convention would be held or

the streets of New Orleans would run with blood. Between July 27 and 30

the negroes of the city were organized and armed, and excited to the

fighting point by radical speakers. The lieutenant-governor telegraphed to

Johnson, asking whether the military officials would interfere if the

courts should order the arrest of the members of the so-called convention,

Judge Abell having stated in a charge to the grand jury that the

convention was illegal. Johnson replied that the military would sustain

the courts. General Baird, who commanded the troops in the absence of

General Sheridan, was asked to station troops near the convention to

prevent a conflict. Baird wired to Secretary Stanton for instructions, but

received none. Stanton, it transpired later, knowing that trouble was

threatened, deliberately withheld the matter from the President and left

Baird without instructions. The courts declared the convention illegal,

but Judge Abell was arrested by the United States commissioner because of

his charge to the grand jury. Governor Wells did nothing in the crisis,

though his sympathies were with the radicals. General Baird, at the

request of Lieutenant-Governor Voorhies, agreed to station troops near the

meeting place of the convention, but was misled by the radicals as to the

time of meeting and the troops arrived too late.

Twenty-nine members met in Mechanics'

Institute at twelve o'clock, July 30. Governor Wells, hearing that a riot

was imminent, deserted his post and left the city. A procession of negroes

marched to the convention hall with flags and music. In front of a

building a negro fired a pistol into a crowd of whites; the latter fell

upon the procession and the riot began. The blacks fled into the

convention hall and fired from windows and doors at the whites. The police

came up at this time and joined in the attack on the blacks, who were

still firing from the building. The whites broke into the hall and shot

and beat and arrested the negroes and conventionists. Forty-four negroes

and four whites were killed and one hundred and sixty-six wounded. The

cause of the riot lay in the inflamed feelings of the whites, who believed

that the radicals at home and in the North were planning to destroy their

political liberty, to disfranchise them, and place them under the rule of

the blacks. The

outbreak furnished valuable campaign material to the radicals. A

congressional committee was sent to investigate. The majority report of

this committee blamed the "rebels" and the President; the minority report

held responsible the radicals, the incendiary proceedings of the

conventionists and the trifling conduct of Governor Wells.

Governor Wells now allied himself openly with

the extreme radicals, and issued proclamations and published addresses

intended to further the plans of those who favored white disfranchisement

and negro Suffrage. He declared that the United States troops would have

to be kept in the state in order to maintain order.

In December, 1866, the legislature met and

remained in session until the passage of the Reconstruction Acts in March,

1867. Governor Wells, in his message, urged the legislature to ratify the

proposed Fourteenth amendment and to provide for negro suffrage. The

proposed amendment was rejected by a unanimous vote. The legislature

discussed again the revision of the constitution of 1864, but nothing was

done before the passage of the Reconstruction Acts. Joint resolutions were

adopted, instructing the attorney-general to test in the courts the

constitutionality of the Reconstruction Acts, but Governor Wells vetoed

the resolutions and assumed authority to proclaim them in force in

Louisiana. An attempt was then made to impeach Wells on charges of

embezzlement in 1840 and unwarranted exercise of authority in 1867. But

General Sheridan at once assumed military control of the situation, and

the Congressional plan of reconstruction was inaugurated.

Congressional Reconstruction, 1867-1868.

Under the Reconstruction Acts Louisiana became

a part of the Fifth Military District commanded by Sheridan.

Lieutenant-governor Voorhies made an attempt to secure the cooperation of

other Southern states for the purpose of testing the Reconstruction Acts

in the courts, but the attempt failed. The conservative leaders, such as

General Beauregard and the members of the legislature, now advised the

people to submit and make the best of the situation.

General Sheridan was a tyrannical ruler. For a

while Governor Wells was retained in office, though subject in all

respects to the military, but on June 3, 1867, Sheridan removed him as an

"obstruction to reconstruction." Thomas J. Durant, the radical leader,

refused the office and it was given to B. F. Flanders. Many other removals

of civil officials were made; among those displaced were Attorney-General

Herron, Mayor Monroe, Judge Abell, nearly all the city officials in New

Orleans and some parish officials. Sheridan insisted that all officials

should actively support reconstruction. Registrars were set to work to

enroll those given the suffrage under the Reconstruction Acts, and before

September, 84,436 blacks and 45,218 whites had been registered.

These figures foretold the nature of the

government that was to be, and in consequence the whites lost heart. At

the voting in September on whether or not a convention should be held,

there were 75,083 votes for holding a convention and against it 4,006,

most of the whites having stayed away from the polls.

The despotic methods of Sheridan caused so

much ill-feeling in Louisiana that President Johnson relieved him, and

offered the command of the Fifth District to Gen. George H. Thomas, who

declined it. Gen. W. S. Hancock was then placed in command. During the

interim between Sheridan's and Hancock's administration, Gen. Joseph A.

Mower was in charge of Louisiana. He was wholly under the control of the

radical leaders at Washington and in Louisiana, and he endeavored to

hasten the process of the reconstruction before Hancock should arrive.

Mower was even more radical than Sheridan; among the many removals made by

him was that of Lieutenant-governor Voorhies. Under Sheridan and Mower no

one was permitted to serve on a jury who was not a registered voter, and

thus the juries fell into the hands of blacks and low-class whites.

"When Hancock arrived he reversed the radical

policy and endeavored to rule justly. He revoked Sheridan's orders in

regard to juries, replaced some officials who had been removed by Sheridan

and Mower, and allowed the civil authorities to perform their functions.

Governor Flanders disapproved this leniency and resigned. To succeed him

Hancock appointed Joshua Baker, a former Democrat who had opposed

secession. On

November 23, six days before Hancock reached Louisiana, the reconstruction

convention met in New Orleans. The negro members outnumbered the white two

to one. The convention was in session until March 7, 1868. The

constitution framed by it disfranchised practically all who had taken

active part in the war on the Confederate side. These could regain the

right of suffrage only by signing a paper stating that the "rebellion was

morally and politically wrong," or by actively supporting the

Reconstruction Acts. Large salaries were provided for $8,000 for the

governor, eight dollars a day for members of the legislature, etc.

Equality of the races was ordered in public places, public conveyances and

in the schools. The convention ordered an election for the purpose of

ratifying the constitution and for the election of state and local

officials. The constitution was adopted by a vote of 51,737 to 39,076,

over 30,000 negroes refraining from voting. The legislature was radical;

H. C. Warmoth, radical, was elected governor, and Oscar J. Dunn, a negro,

lieutenant-governor. Warmoth, who was from Illinois, had been a Federal

soldier, but had been dismissed for expressing too strong Democratic

sentiments. Hancock

left Louisiana before the legislature met. He had, during the winter,

removed some of Sheridan's appointees who had proved to be corrupt.

General Grant ordered them reinstated and Hancock thereupon asked to be

relieved. Gen. E. C. Buchanan succeeded him and completed the

reconstruction of Louisiana. The legislature met in June, ratified the

Fourteenth amendment and elected two carpet-baggers, William P. Kellogg

and John S. Harris, to the United States Senate. General Buchanan then

placed Warmoth and Dunn in charge of the government, and on July 13

declared Louisiana "reconstructed."

The Administration of Governor Warmoth,

1868-1878. For

more than eight years 1868-1877the government of Louisiana was

controlled by adventurers from the North and a few native corruptionists

kept in power by the votes of degraded and ignorant blacks, and by the

armed forces of the Federal government. Dishonesty in public office was

the rule, not the exception. Governor Warmoth's accession to office was

followed by a short period of tranquillity, but the seeds of discord had

been sown and soon the trouble came. During the presidential campaign of

1868 there were serious conflicts between the blacks organized in the

Union League and the whites, who belonged to secret orders such as the

Caucasian Clubs, Knights of the White Camelia, etc. Dangerous riots

occurred in New Orleans and in St. Landry Parish. In order to give the

carpet-bag state government military protection, the legislature, in 1868,

provided for a body of armed men known as the Metropolitan Police, which

was transformed by the governor into a small standing army, subject to his

absolute control. The governor also had large powers of appointing and

removing greater than was ever enjoyed by the governor of any other

state. The law

forbidding separate public schools for the races caused the whites to

become hostile to the school system, and they refused to allow their

children to attend. The schools fell entirely into the hands of the

negroes. Soon the embezzlement of the school funds by the officials

seriously interfered with the operation of the negro schools. The Pea-body

Education Fund paid to the white private schools the share of its money

due to Louisiana. The Louisiana State University at Alexandria, which,

after the destruction of its buildings in 1869, was located temporarily at

Baton Rouge, refused to open its doors to negroes, and in consequence,

after 1872, its appropriations were withheld and it slowly went to ruin.

Though the Louisiana State University (then

called the State Seminary) was not mentioned in the constitution of 1868

as an institution that must open its doors to negroes, the old University

of Louisiana, a New Orleans institution, was directed to admit both races

to its law, medical and academic departments. This seriously crippled the

institution, though there is no evidence that any negroes ever attended.

The state debt rapidly grew to enormous

proportions. In January, 1869, it amounted to $6,777,300; a year later it

was $28,000,000, and in November, 1870, it reached $40,000,000. Local

debts were heavy also, that of New Orleans reaching $17,000,000 in 1870.

Warmoth denounced the legislature for bribery and corruption. He said that

he himself was offered $50,000 to sign a bill. The mere running expenses

of the legislature in 1871 were as follows: Senate, $191,763.85; House,

$767,192.65 an average of $113 a day for each member. The House had

eighty clerks at high salaries, yet only 120 bills were passed.

Warmoth, though corrupt as any, frequently

showed signs of a better spirit. In 1869 he secured the passage of a

general amnesty act. He endeavored to make a compromise by which the races

might have separate schools in spite of the constitution, and though he

grew rich while in office, he loudly denounced the worst of the thieving

by others. His attitude in this matter caused him to be severely censured

by the baser elements of his own party, and he drew toward the Democrats.

By 1871 the Republican party split into two factions, one headed by

Warmoth and supported at times by Democrats; the other known as the Custom

House faction was composed of the leading carpet-baggers, headed by S. B.

Packard, United States Marshal, and George W. Carter, speaker of the

House. This faction wanted to impeach Warmoth and thus get control of the

spoils. In 1871 Lieutenant-governor Dunn died, and Warmoth managed to get

another negro, P. B. S. Pinchback, a creature of his, elected to the

vacancy. For some weeks early in 1872, a state of war existed between the

two factions. Warmoth's friends were once shut out of the legislature and

he himself arrested under the Enforcement laws and haled before Packard.

Next he used his great influence to have Carter deposed as speaker of the

House. Carter and Packard then organized another body which they called

the "true legislature," and raised forces to seize the State House.

Conflicts occurred in the streets, and a mob raised by Packard and Carter

was kept out of the State House only by the aid of Federal troops.

The Kellogg Usurpation, 1872-1877.

When the presidential campaign of 1872 opened,

Warmoth and his faction declared for the Liberal Republicans and united

with the Democrats. The Custom House faction declared for Grant, and

nominated for governor William Pitt Kellogg, and for lieutenant-governor

C. C. Antoine, a negro. The Democratic nominees, John McEnery for

governor, and Davidson Penn for lieutenant-governor, were supported by

Warmoth and received a majority of the votes.

But the problem of counting the votes was most

complicated. To count the ballots and declare the results was the duty of

the Returning Board. Three members of the board being candidates were no

longer eligible, and Warmoth appointed others to take their places. Then

the three who had thus lost their places formed a new body known as the

Lynch board, and Kellogg got an order from Judge Durell restraining the

other board from counting the votes. Warmoth, not to be beaten, now signed

and promulgated a bill passed by the last legislature which gave to the

Senate the appointment of the returning board, called the Senate to meet

and elect a board, and meanwhile appointed, as he had the authority to do,

a temporary board known as the De Feriet board. By this board McEnery was

declared elected.

President Grant, in accord with his usual policy in Southern affairs,

sided with the radical party, refused to recognize the count of the De

Feriet board, ordered the troops to support the other faction, recognized

as acting governor the negro Pinch-back, whose term of office as

lieutenant-governor had expired a month before, and accepting the

impeachment of Warmoth by the Kellogg faction, ordered the dispersal of

the McEnery administration. Committees of citizens were organized to go to

Washington to lay the case before President Grant, but the latter sent

word that the visit would "be unavailing." In January, 1873, Kellogg

succeeded Pinch-back and the Kellogg legislature began its session.

But the McEnery government did not entirely

cease to exist. There were country districts where the people recognized

it alone, and here and there bodies of militia were organized to support

it. A congressional investigating committee declared that McEnery was the

de jure governor, and recommended that an election be held under Federal

control in order to give Louisiana a government which the people would

support. This proposal was rejected by the radicals in Congress. Kellogg

could enforce his laws only by using the Metropolitan police and the

Federal troops. Riots occurred frequently; six office-holders were shot in

Red River parish; in Grant parish there was a pitched battle between the

whites and the blacks; in St. Martin's Col. Alcibiade de Blanc, who had

been the head of the White Camelia, raised a force of whites and drove out

the Metropolitan police sent by Kellogg to force the people to pay taxes;

in New Orleans a body of whites attacked the police stations, but were

repulsed by the police and the soldiers. In March, 1873, all the

Democratic members of the legislature were thrown into prison. It was

clear that Kellogg would not be able to rule the country districts, and

would have difficulty in holding New Orleans.

For a while the Democrats of Louisiana had

done as in other Southern states, that is, had tried to form a party

composed of both races. This had failed in every state. But the year 1874

marks the beginning of the widespread "white man's movement" which finally

cast out the reconstructionists. In Louisiana this movement was swiftly

organized into "The White League," with the best men of the state as

leaders. The White League declared for free government by white men. In

August, 1874, a state convention of the order was held in Baton Rouge. It

was evident from the proceedings that revolution was at hand.

During the next month arms were gathered, the

militia organized and drilled, and plans made for the overthrow of the

Kellogg government. On September 14 a mass-meeting in New Orleans demanded

the resignation of Kellogg, who fled to the United States Custom House to

the protection of the Federal troops. The White Leagues assembled, were

organized as state troops under Gen. Frederick N. Ogden, and ordered to

attack the Kellogg Metropolitans under Generals Longstreet and Badger. The

latter made but slight resistance and the city fell into the hands of the

whites. McEnery being absent, Lieutenant-governor Perm was formally

inaugurated on September 15, and peace seemed at hand. But President

Grant, faithful to his policy, refused to recognize the white government,

sent troops and war-vessels to New Orleans and ordered General Emory to

replace Kellogg. This was done without resistance the whites always

making it a point not to resist Federal troops and the city again fell

under Kellogg's control.

Though the radicals controlled the election

machinery, the elections in November, 1874, went in favor of the white

party. They elected fifty-seven representatives to fifty-four for the

radicals, four of the six members of Congress, and several state officers.

But the returning board under J. Madison Wells counted in a radical

majority for the House and the radical state officers. To support this

count President Grant ordered Sheridan to New Orleans, with instructions

to take command if he saw fit.

The legislature met on Jan. 4, 1875. Kellogg's

guards excluded the Democrats who had been counted out by the returning

board, but the remainder, some of the radicals being absent, elected L. A.

Wiltz speaker, and admitted to seats the contesting Democrats. Kellogg

then sent Colonel De Trobriand with Federal troops to eject nine

Democratic members. When this was done the other Democrats, led by Speaker

Wiltz, left the hall. The radicals then elected Michael Hahn speaker.

Sheridan telegraphed to Grant that if the latter would declare the members

of the White League to be banditti, he, Sheridan, would do all else that

was necessary, that is, hang them when caught.

So great was the indignation everywhere

aroused by the high-handed acts of Kellogg, Sheridan and Grant, that

Congress sent a committee to Louisiana to adjust affairs. This committee

framed an agreement, which the Conservatives ratified, known as the

"Wheeler Adjustment." By this compromise all of the Democratic members of

the legislature were seated, and the Democratic majority thus created in

the lower house agreed not to impeach Kellogg for any acts committed prior

to the adjustment. This was all that the white man's party could expect

while Grant remained president.

After the Wheeler Adjustment there was

comparative quiet in Louisiana until the fall of 1876, when the

presidential campaign began. In the lower house of the legislature an

attempt was made to abolish the corrupt returning board, but Kellogg and

the Republican senate defeated the measure. Other attempted reforms

failed, but with a Democratic House no dangerous laws could now be passed,

and there was even some constructive legislation. An investigating

committee found that the governor and auditor were guilty of

misappropriating public funds and recommended the impeachment of both.

Governor Kellogg was impeached by the House for offenses after the Wheeler

Adjustment, but the Senate, by giving less than an hour for the

preparation of the case, defeated the impeachment.

In the campaign of 1876 state issues, rather

than national affairs, interested the people of Louisiana. Every effort

was made by the whites to secure control. Gen. F. T. Nicholls was the

Democratic candidate for governor, and S. B. Packard, of unsavory fame,

was the candidate of the negro Republican party. The whites, encouraged by

previous partial successes and by Democratic victories in other states,

were confident, and used their influence to secure peaceful elections. The

result was the quietest election held since 1866. The Democrats secured a

large majority, but the returns had still to be counted by the returning

board, of which J. M. Wells was president.

On the day after the election it became

evident that if Hayes failed to secure every electoral vote from the three

Southern states where the count was disputed Louisiana, South Carolina

and Florida Tilden would be elected president. So the Republicans

claimed the votes of all these states. President Grant invited a committee

of prominent Republicans to visit each of the disputed states to watch the

count. The Democrats also sent "visiting statesmen. '' Wells offered the

vote of Louisiana to Tilden for a million dollars, but the offer was not

accepted. The other side made good offers, and the Republican state and

presidential tickets were declared elected. The Democrats sent contesting

returns to Washington, and the matter was not settled in favor of Hayes

until the last days of Grant's administration.

Meanwhile, in January, 1877, both Nicholls and

Packard were installed as governors in New Orleans, and the White League

militia again marched out and took possession of the city. General Grant

was for the first time slow to send military aid to the radicals. The

whites recognized only the Nicholls government. By a sort of trade between

the Democrats and Republicans at Washington, the vote in Louisiana was

allowed to be cast for Hayes, while in return the Democratic state

governments in South Carolina, Louisiana and Florida were to be recognized

as legal. Consequently when Hayes became president he gave no support to

Packard, who was governor of Louisiana by as much right as he, Hayes, was

president. On April 29 the troops were withdrawn and the Packard

government went to pieces. Kellogg, who had been chosen United States

senator by the defunct Packard legislature, was admitted, while Henry M.

Spofford, who was elected by the Nicholls legislature, which was

recognized by the President as the legal legislature, was not seated.

By the trading the whites secured nearly all

that they wanted, but the policy of the "Washington administration was

disgraceful. The leading carpet-baggers and scalawags were given Federal

offices, and most of them left the state.

So ended the reconstruction experiment in

Louisiana. Its results were for the most part bad. The whites were

afterward solidly Democratic while the opposing party was not respectable;

the whites had become intensely opposed to any real participation in

government by the negro; the constant struggle against the corrupt and

oppressive carpetbag-negro government and the necessary use, at times, of

violent methods resulted in lessening respect for law and government. The

races were made unfriendly; in character neither white nor black had

profited by the struggle in the mire of reconstruction; the public schools

in the state had ceased to exist; the State University had been four years

without appropriations. The extravagant corruption of the carpetbaggers

had left the state bankrupt; long years of economy and heavy taxation were

necessary before the finances were again in good order. During the

reconstruction there had been no economic progress; in 1877 the state, in

wealth and products, was far behind what it was in 1860. To heal the

wounds of war and reconstruction was the task of a generation.

Bibliography. Annual Cyclopedia, 1860-1877

(New York, 1861-1878); Ficklen, J. R.: Reconstruction in Louisiana, to

1868 (in Mss.); Fleming, W. L.: Documents Relating to Reconstruction

(1904); Fleming, W. L.: Documentary History of Reconstruction (2 vols.,

Cleveland, 1906-1907V. Fortier, Alc้e: History of Louisiana, Vol. IV. (New

York, 1904); Phelps, Albert: Louisiana (Boston, 1905).

Walter L. Fleming,

Professor of History, Louisiana State University. |