|

UNLIKE Gaul, all

Aberdeenshire was divided into five parts. These were the districts

of Mar, the Garioch, Strathbogie, Formartinc and Buchan, a division

which still has a definite signification.

The district of the

Garioch is bounded on the south-west by Mar, on the north-east by

Formartine and Buchan, and on the north-west by Strathbogie. It has

an area of about fourteen miles by eight — the largest diameter

passing in a north-westerly direction from Ardiherald in the east,

so named in Gordon of Straloch’s map, towards the Huntly boundary of

the district in the north-west. It is largely a valley between hills

to the north and south, for the hilly range of Bennachie, though

regarded as essentially a Garioch mountain, is placed by Straloch

just outside the southern boundary of this district. The valley is

abundantly watered by tributaries of the Ury, which has a confluence

with the Don a little to the south of the ancient and royal burgh of

Inverurie, the capital of the district. Thus situated, the

peacefulness of later times, and the industry of its population,

have rendered the Garioch “the Granary of Aberdeenshire.” A visitor

to the district is struck on the whole by a comparative absence of

woodland. There is sufficient evidence, however, that this was not

so always. The forest country in the neighbourhood of Kintore, lying

to the south of Inverurie, was probably more or less continuous with

woodland in the Garioch, and, as we shall learn later, the Garioch

had its own Forester, originally a vassal of the Earl of Mar, and

later of the Crown.

In the end of the

twelfth, or beginning of the thirteenth century, the Garioch emerges

from the rule of the Celtic Maormars, and their vassals the Toisechs,

as an Earldom, in the person of David, Earl of Huntingdon, the third

son of King David I. of Scotland. From that period comes into

clearcr light the mutual struggle and assimilation of North and

South, of Celt and stranger, whether Saxon, Norman, or Norseman, in

this district of Aberdeenshire. That interesting Crusader, Earl

David, does not seem to have retained the Earldom long, which was

next conferred upon a natural son of King William, whose heir dying

childless, it was granted to William Comyn by Alexander III. After

the defeat anti forfeiture of the Comyns by Robert the Bruce, the

Earldom of the Garioch sank to a Lordship, and appears to have been

given as such by that King, possibly as a marriage portion, to his

sister, Christian Bruce, and her husband, Gratney, Earl of Mar, who

was already his brother-in-law, the King having married the daughter

of Donald, Earl of Mar, and the sister of this Gratney.

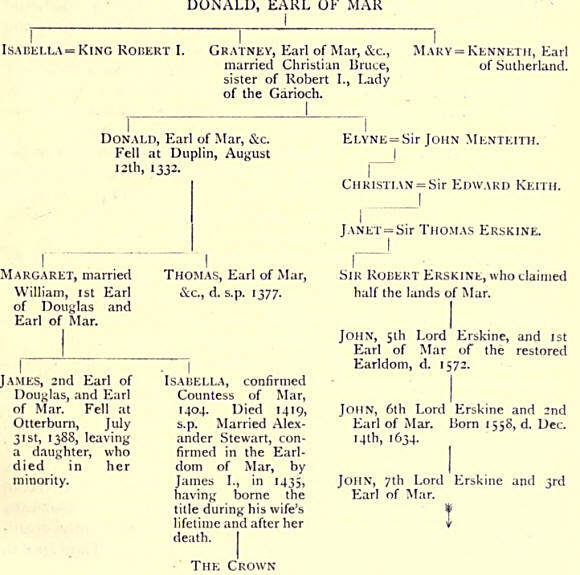

In view of the future

development of this narrative, it will be convenient in this place

to deal as shortly as possible with the genealogical history and

relation to the Garioch of the Mar family.

Donald, Earl of Mar,

was succeeded by his son, Gratney, who, as has been stated, married

Christian Bruce. This Countess of Mar seems to have been Lady of the

Garioch in her own right, for she grants charters within the

regality in that capacity. She carried the Lordship to her husband

and her descendants. They had a son, Donald, who succeeded as Earl

of Mar and Lord of Garioch, and was slain at the battle of Duplin in

1332, and a daughter, Elyne, who married Sir John Menteith. Donald,

who fell at Duplin, left a son, who succeeded him, and was the last

male of his race, dying without issue, and a daughter, Margaret,

who, with her husband, William, first Earl of Douglas, succeeded her

brother. She was the mother of her successor, James, Earl of Mar and

Douglas—the “ kindly Scot,” who fell at Otterburn, without

succeeding issue, in 1388. He was succeeded by his sister, the

Countess Isabella of Mar, who also died without issue, but after

transferring the Earldom to her somewhat unceremonious wooer and

husband, Alexander Stewart, the illegitimate grandson of King Robert

II., and in 1411 the victor of Harlaw. From this transaction a good

deal of future trouble sprang. The instrument of transfer was dated

August the 12th, 1404, and vested the succession in their immediate

heirs, whom failing, in the husband’s heirs. Anxious to give his

acquisition of the Earldom an air of less compulsion, Alexander

Stewart renounced this deed on September 9th of the same year, and

on December the 9th, 1404, a charter giving the succession to the

Countess Isabel’s heirs, in the absence of legitimate descendants ol

herself and Alexander Stewart, received the sanction of Robert III.

(Lord Crawford’s Earldom of Mar, p. 204, et. seq.) Isabel died in

1419, without issue, and Alexander, Earl of Mar, her husband, still

enjoyed the lands and privileges of the Earldom. Although his

services at Harlaw were now a matter of history, he was apparently

dissatisfied with the authority carried by the sanctions of the

discredited Duke of Albany, sometime Regent of Scotland, and

resigned his status and possessions into the hands of James I., who

thereupon granted a charter on the 28th of May, 1426, by which the

Earldom should at Alexander’s death devolve on the latter’s

illegitimate son, Sir Thomas Stewart, and, after the death of Sir

Thomas and the failure of his lawful issue, return to the Crown. Sir

Thomas Stewart predeceased his father without legitimate issue, and

on the death of the Earl himself in August, 1435, the Earldom and

its patronage vested in the Crown in virtue of the terms of the

grant. The King thus purposely ignored the asserted legitimate

blood-claim of Sir Robert Erskine, the great-grandson through two

female descents of Lady Elyne of Mar, the daughter of Gratney, Earl

of Mar, and Christian Bruce. In the pursuance of a larger state

policy, regia voluntas suprema lex, appeared to be a flawless maxim

to the early Jameses, and what Robert III. confirmed, James I.

annulled, the legal value of the charter not depending upon any

question of abstract justice, but upon the royal sanction of a

feudal king—the overlord of all his vassals. But, and this is a

point to be borne in mind, in view of future developments, so far as

they concern our present purpose, the legal force of charters

granted by Alexander Stewart, as Earl of Mar, during his life time,

could not be righteously disputed. It was disputed nevertheless, as

we shall learn in due course. From this time (August, 1435) until

1565, when Queen Mary restored the Earldom of Mar in the person of

John, fifth Lord Erskine, the representative of the displaced Sir

Robert Erskine, the Crown or its representative administered all the

functions of the Earldom of Mar and Lordship of the Garioch. Queen

Mary, however, moved, it is said, by compunction at the iniquitous

conduct of her predecessors, restored the Earldom at the above date

to the Erskine line, not, however, before having conferred that

title in 1561, on the occasion of his marriage with the Earl

Marischal’s daughter, upon her father’s illegitimate son, James

Stewart, subsequently Regent of Scotland. She also conferred with

the title such lands pertaining to it, as were at that time not

allotted to other persons. James Stewart, Karl of Mar, did not,

however, long retain that Earldom, and exchanged it for the Earldom

of Moray, which became his after the fall from favour of the

inconveniently interposing Earl of Huntly. Mary, a true daughter of

the old faith, had thus no apparent compunction in conniving at the

sacrifice of the strongest prop at that time in Scotland, of the

faith in which she died, yet, she is represented as hurt at the

notion that her predecessors should have deemed it advisable to

distribute the Mar estates and resume the immediate superiority of

Mar and the Garioch. No, the theory of royal compunction in the

matter of the Mar peerage cannot be maintained. The Regent Moray was

the illegitimate son of James V., by a daughter of the fourth Lord

Erskine, and sister of John, fifth Lord Erskine, also Regent of

Scotland, in whose person the old Earldom of Mar was restored,

according to some, or a new Earldom of that name created, in the

opinion of others. In view of these circumstances, it is much more

probable that the influence of Moray and the Erskines had a good

deal more to do with the restoration than any compunction on the

part of the Queen as to an injustice perpetrated by her

predecessors. That compunction of Mary’s is doubtless a fa^on de

parler. It will be noted, however, that in granting the title to

James Stewart, the Queen only gave with it such lands as the Crown

at that time retained.

Mary now leaves our

narrative, and is succeeded by her son, James VI one of whose

companions, from his youth up, was John Erskine, Earl of Mar, born

about 1562. He became known as one of the most powerful persons at

the Court of that monarch. The personal ambition of this astute

nobleman seems to have been, not only to wear the ancient dignity to

which his family considered themselves entitled, but also, if

possible, to recover all the lands or fiefs which once belonged to

the Earldom of Mar. This ambition, if realised, would have added

largely to the revenues of the family, at a time when no one in

Scotland was rich. In furtherance of this aim, he instigated that

action of the Scottish parliament, which in 1587 decided that the

ancient possessions of Mar still appertained to the restored

Earldom. But the mere necessity for such action, and the terms of

the grant to James Stewart, prove that the Act was passed to clear

the way for further action in the attempt to recover these lands,

most of which had been held for generations by families which had

rendered doughty service to the Crown in the interval,

and paid the blood

tax at Flodden and at Pinkie. Nay, in the legal processes which

arose out of this matter, the language of insult was not wanting. In

an action by the Earl of Mar to “reduce” Duguid of Auchinhuive, that

member of a county family of repute is curtly described as “one

Duguid,” and a trespasser. With the later developments of the

history of the Mar peerage we are not concerned, but the bearing of

the circumstances just related on the present narrative will appear

in due course. These genealogical facts concerning the succession to

the Earldom of Mar may be conveniently presented in the following

tabular form :—

|