APPENDIX

INTRODUCTION

This monograph* began as an address to the Celtic

Society of Wolfville, Nova Scotia. So many challenging questions were

raised that a systematic study was undertaken by its author, in order to

prepare a toponymical roster and to analyse its significance.

* From Watson Kirkconnell, "Scottish Place Names in

Canada," A Paper Delivered at the Third Annual Meeting of the Canadian

institute of Onomastica Sciences, York University, Toronto, June 13,

1969, in J.B. Rudnyckyj, ed., Onomastica, No. 39 (Winnipeg,

1970).

THE PEOPLES AND SURNAMES OF SCOTLAND

At the outset, one should remember that Scotland,

from which the Scottish Canadians have come, is not homogeneous in

either race or language. In other words, there is no "Scotch race" and

no "Scotch language." The ethnologist, whose definition of race is based

on physical characterisitcs and measurements, distinguishes carefully

between the flaxenhaired ex-Scandinavians in the extreme north, the

"Black Breed" in the Western Highlands, the red-heads in the Eastern

Highlands, the tall, dark-haired, blue-eyed Galwegian blend, the short,

dark Strathclyde type, and the Anglo-Danish mixture of the Lowlands

generally. So far as language is concerned, the English of the Lowlands

is still waxing and the Gaelic of the Highlands is waning. The Welsh

language of the Kingdom of Strathclyde, which persisted from the fifth

century until the eleventh, has disappeared, and the Norse that was

spoken in the Shetlands as late as the eighteenth century survives only

in a host of place-names and dialect terms. Still older linguistic

traces, found on Roman maps and no doubt borrowed by them from

primordial people, are the Clyde (Clota), the Nith (Novius),

the Hebrides (Hebudes) and the Orkneys (Orcades).

Clan-names, while not identical in pattern with the racial and

linguistic background, are nevertheless clear evidences

as to diversity of national origins. Gaelic in origin are the clan-names

Angus, Campbell and MacGregor. Norman-French are Bruce, Cummings,

Fraser, Grant and Sinclair. Ultimately Norse are Gunn, Lamont,

Macdonald, MacLeod, MacNeill (of Colonsay) and Sutherland. English are

Johnson, Leslie and Stewart (although this final family was originally

Breton and came over with the Normans).

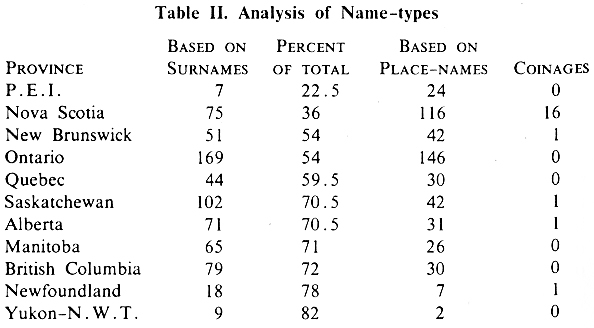

Since the majority of Scottish place-names in Canada

are actually based on surnames, some analysis of the latter is in order.

The main types are occupational, descriptive, patronymic and

territorial. Examples hereunder will be limited to actual place-names in

Canada.

Examples of occupational names are Avenir (OF.

avener, oat merchant), Faulkner (falconer), Gardiner (gardener),

Lymburner (lime-burner), Milner (miller), Pender (impounder of strayed

cattle), Sclater (slater), Sellars (M.E. seler, a saddler),

Shearer (cutter of cloth), Spence (dispenser of food from the larder)

and Stewart (originally the "steward" or chief manager of the royal

household). Patronymic derivatives of occupational names are Macoun or

Macgowan (son of the Gow or blacksmith) and MacIntyre (son of the

carpenter).

Descriptive names are Auld (old), Young or Yonge,

Baine (G. ban, white or flaxen-haired), Reid (red-headed), Duff

(F. dubh, dark), Campbell (G. Caimbeaul, crooked

mouth), Cameron (G. cam-shron, hooked nose), Strang, strong, or

else OF. estrange, a foreigner), and Tod (nickname, "the fox").

Patronymic names may be Scandinavian (with a

suffixed-son), Gaelic (with a prefixed Mac "son of"), and English

(with a suffixed genitival -s).

Formed on the Scandinavian model are Allison (son of

Ellis), Anderson (son of Andrew), Dawson (son of Dawe or David),

Ferguson (son of Olr. Fergus, the grandfather of Saint Columba),

Jameson (son of James), Matheson (son of Matthew), Paterson or Patterson

(son of Patrick), Ni-colson (son of Nicol), Robertson (son of Robert),

Robinson (son of Robin), Simpson (son of Sim or Simeon).

Gaelic patronymics have a wide range of application.

Based on straight personal names are MacAdam (son of Adam), MacAlister

(son of Alexander), MacAlpine (son of Ailpean), MacArthur (son of

Arthur), MacAulay (son of Amhalghaidh), MacCormack (son of Cormack),

MacCreary and Macrorie (son of Ruadhri), MacEwen (son of Ewen),

MacFarlane (son of Bartholomew), MacGregor (son of Gregory), MacKay or

MacKee (son of Aodh), MacKendrick (son of Henry), MacKenzie (son of

Coinneach), McKim (son of Simon), MacKinnon (son of Fhionnghain),

MacLaren (son of Laurence), MacLaughlin (son of Lachlann), MacMahon (son

of Matthew), MacMurdo (son of Murdoch), MacNaughton and Mac-Cracken (son

of Neachdain), MacNeill (son of Neill), MacTavish (son of Tammas, i.e.

Thomas), MacVeigh (son of Bheatha), MacWatters (son of Walter).

Of special note are Macdougall or Macdowall (son of Dougal, eldest son

of Somerled, Norse Lord of the Isles), Macdonald (son of Donald, eldest

son of Reginald, second son of Somerled), Maclver (son of Ivarr, a

famous Norse chief), and MacKellar (son of Hilarius, bishop of Poitiers).

A common ingredient in many old names was the Gaelic Gille,

"servant," applied especially to those who were consecrated to the

service of a saint or of the church in general. This was an element in

the older forms of the following surnames: MacBride (son of the servant

of Bride, the virgin abbess of Kildare, d. 525), MacCallum (son of the

servant of Calum), McClintock (son of the servant of St. Findan),

MacLean (son of the servant of St. John), MacLesse (son of the servant

of Jesus), MacLen-nan (son of the servant of St. Finnan), McLure (son of

the servant of Odhar), McMunn (son of the servant of St. Munn). Also

associated with the church are MacMillan (son of the tonsured man),

Macnab (son of the abbot), MacPherson (son of the parson), and

MacTaggart (son of the priest). More general are MacEachern (son of the

horse-lord), Macintosh (son of the chieftain), McKague (son of Olr.

Tadhg, or the poet), McNeily (son of the poet), MacGillivrary (son

of the servant of judgment), and MacLeod (probably, son of an old Norse

warrior, Ljot-ulf, "ugly wolf").

Many a Highland name can shift gears into a Lowland

equivalent, depending on the habitat of its owner, e.g. MacIan (MacKean)-Johnson,

Macdonald-Donaldson, MacAdam-Adamsonn, MacNeill-Neilson,

Mac-Nichol-Nicholson, MacTavish-Thomson, and MacMahon-Matheson.

Examples of the English genitival suffixes are

Sellars and Watts.

Hundreds of Scottish surnames are of territorial

origin, i.e. they represent the family's original estate or feudal

lands. Since these are also place-names, there is often a doubt as to

which came first in the Canadian toponymy, the hen or the egg. Wherever

the place-name has had wide currency in Scotland as a surname, it has

seemed reasonable to count it as a surname in Canada. Thus Gordon

is the name of a little place in Berwickshire with which some

genealogists first associate the family, but it is undoubtedly the

family and not the obscure village that is recorded on the Canadian map.

Similarly, although the name Douglas is derived from the "black

water" (G. dubh glas) of a stream in Douglasdale, it is the

family and not the river that is set down in Canadian gazetteers. In

like manner, Blair, Buchan, Caldwell (i.e. "cauld well"), Cochrane,

Dundas, Drummond, Glenelg, Harris, Kippen, Lewis, Lumsden, Ross, Selkirk

and Sutherland would all seem to have been chosen as Canadian

place-names on a surname basis.

SCOTLAND'S MAP AND THE MIGRATIONS

My preliminary survey of place-names by shires on

Scotland's map was undertaken hand in hand with the reading of J.M.

Gibbon's Scots in Canada (Toronto, 1911), Wilfred Campbell's

The Scotsman in Canada: Eastern Canada (Toronto and London, 1911),

George Bryce's The Scotsman in Canada: Western Canada (Toronto

and London, 1911), and Hazel C. Mathews's The Mark of Honour

(Toronto, 1965). It became evident that the bulk of Eastern Canada's

Scottish place-names were to be associated with mass migrations in

1770-1840 from Inverness, Argyle, Ross, Sutherland, Caithness,

Perthshire, Moray, Skye and the Hebrides. In this period, thousands of

crofters were being evicted from the glens, partly by their old

chieftain-landlords and partly through the destruction of cottage

weaving by the Industrial Revolution. A considerable element in the

settlement consisted of Highland regiments which, after Culloden and the

defeat of the Jacobite uprising of 1745, had been recruited into the

British army, especially after 1757. Marion Gilroy's record,

Loyalists and Land Settlement in Nova Scotia (Public Archives of

Nova Scotia, 1937), shows heavy land grants to Loyalist immigrants,

mostly Highland veterans, after 1783, in what are now the counties of

Shelburne, Digby, Annapolis, Antigonish and Guysborough. Not a single

Loyalist grant was made in Horton and Cornwallis townships, Kings County

which had been solidly settled by New England "Planters" in 1761, nor in

the Lunenburg South Shore area, settled in 1749-53 by Germans, Swiss and

French Huguenots. In Hants County, in a proposed township of "Douglass,"

a whole battalion of the 84th Highland Regiment simply evaporated,

leaving 115,000 acres to escheat to the crown. Most of those in

Shelburne left the country before 1800, but an island of Highland

population persists in the "Argyle" area, between the Acadians of

Pubnico and the Acadians of Clare. After the close of the Napoleonic

Wars, and especially after 1820, a severe economic depression swept the

industries of the Scottish Lowlands and these also poured their harassed

citizens into Canadian settlements.

Mostly unrepresented in Nova Scotia are place-names

from the shires of Ayr, Banff, Berwick, Bute, Dunbarton, Kincardine, the

Lothians, Nairn, Peebles, Roxburgh, Selkirk, Wigtown and Kirkcudbright.

Immigrants from these areas either came too late to affect the naming of

communities or did not set up the block settlements that so often

perpetuate their own choice of names.

All parts of Scotland are represented in the

place-names of Prince Edward Island; their gross number would have been

much greater had it not been for a plague of absentee landlords and for

the ambitions of surveyors and political persons to have their

names perpetuated. Settlement goes back to the enterprises of Judge

Stewart, of Cantyre, Argyllshire, in 1771; of Captain John MacDonald, of

Glenaladale, in 1772; and of Wellwood Waugh, of Lockerbie, Dumfriesshire,

in 1774. In 1803, Lord Selkirk brought in a contingent of 800 from Ross,

Inverness, Argyle, and especially Skye.

The pattern of Scotch place-names in New Brunswick is

not unlike that in Nova Scotia, although there is nothing like the

continuing Highland concentration in Cape Breton and Antigonish. In the

1780s, the Loyalists established several regiments (largely Scotch) on

the St. Croix and St. John rivers; and there were settlements, direct

from Scotland, on the Lower Miramichi and in the county of Restigouche.

This latter plantation, largely of fisher-folk, on the Restigouche River

and its estuary, has been buried under a community of Acadian French who

swarmed in here from exile when the interdict on their presence was

removed in 1764.

In Lower Canada, the ultimate province of Quebec, the

most important Scottish settlements were those of the Fraser

Highlanders, whose mountaineer regiment had scaled the Heights in 1759

and won the battle of the Plains of Abraham.

In Ontario, where no fewer than eleven counties

(Bruce, Carleton, Cochrane, Dundas, Elgin, Glengarry, Lanark, Lennox,

Perth, Renfrew and Stormont) bear Scottish names, the roster of Scottish

place-names is by far the largest in all Canada, yet early mass

settlements left a special mark. Such were the Roman Catholic regiments

of Glengarry, the Talbot settlements of Argyle Highlanders in Elgin

county, the Sutherland crofters in Zorra, and the thousands from Lanark,

Renfrew and the west of Scotland who flocked to Lanark county in

1820-21. Veteran resettlement (as in the days of the Caesars) and

economic hardship in Scotland were major factors in the situation.

The opening up of the Western provinces came at least

two generations later. Not only did immigration agencies (including

those of railways and steamship lines) then recruit from all parts of

Scotland; but, thanks to the C.P.R., the younger sons of Scotch-Canadian

farmers in Ontario swarmed to the Prairies in their thousands. Still

earlier had been the striking participation of Scots in the fur trade

activities of the Hudson's Bay Company and the Northwest Company. They

also played the leading role in the drama of exploration that put the

names of Fraser, Simpson and Mackenzie on the maps of the Canadian West

and North.

It is sometimes interesting to look for traces of a

single known migration. Thus in 1774 a considerable settlement of

Lowlanders from Dumfriesshire came to Prince Edward Island. Three years

later some of the group, overwhelmed by a plague of grasshoppers, joined

the Protestant Highlanders at Pictou. Today, in Prince Edward Island,

there is still a "New Annan," and on the mainland, thirty miles

northwest of Pictou, there is another "New Annan." Other Dumfriesshire

place-names, ascribable to other, later migrations, are Annan, Kirkland

(Lake), Moffat and Thornhill in Ontario, Gretna and Thornhill in

Manitoba, Bankend in Saskatchewan, and Kirkpatrick in Alberta.

On the other hand, a very considerable contingent of

Highlanders from Glenlyon, Perthshire, who settled on the north shore of

the Ottawa River near Lachute in 1819, have left no toponymic trace

except for Thurso (Caithness) and Lochaber Bay (Inverness), neither one

relevant to the area of their origin. After 150 years, a substantial

remnant of lineal descendants is still in the area of settlement.

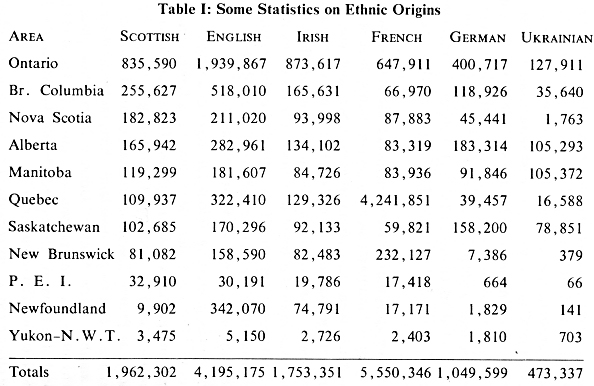

THE SCOTS IN THE CENSUS

When in a search for the place of the Scots in

Canadian life one turns to the Federal Census of 1961, one arrives at

the following Scottish totals by provinces, as compared with Canadians

of English, Irish, French, German and Ukrainian origin. The provinces

are printed in the descending order of Scottish representation.

These statistics do not reveal their full

significance at a first glance. Thus the 835,590 Scots of Ontario, while

they are almost as numerous as all the other Scots in Canada put

together, are nevertheless inferior in Ontario to either the English or

the Irish and only 29 per cent more numerous than the French. The only

province where the Scots are clearly in first place is little Prince

Edward Island. The Scots are in second place, behind the English, in

Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Manitoba and British Columbia. Both the

English and the Irish outnumber them in Newfoundland; while in Alberta

and Saskatchewan they rank numerically behind the English and the

Germans. Even in the frontier areas of the Yukon and the Northwest

Territories, they run second to the English. Another sort of yardstick

is the survival of Gaelic in Nova Scotia, where 3,702 (mostly in Cape

Breton) in the 1961 Census still reported it as their mother tongue.

Although the English in Canada outnumber the Scots by slightly more than

two to one, their ratios to the present total populations of their

respective mother countries form a striking contrast; for while the

English-Canadians are equivalent to 9½

per cent of England's 1961 population, the Scotch-Canadians are

equivalent to 38 per cent of Scotland's population. The Canadian Irish

are similarly equivalent to 41 per cent of the total population of

Ireland (North plus South). At the time

of Confederation, in 1867, the Scots and the Irish together outnumbered

those of English extraction and played a very prominent role in the

politics of the new nation. Some 20 of the 34 "Fathers of Confederation"

were Scots. The ingredients of these three peoples (English, Irish,

Scotch) in Canada's national amalgam is thus very different from that in

the "British Isles." The presence of a French sub-nation is another very

difficult factor, and now we have nearly five million European-Canadians

who are neither British nor French. The Canadians are to be a national

blend sui generis.

UNFULFILLED BLUEPRINTS FOR "NOVA SCOTIA"

In 1613, (Sir) Samuel Argall, a Kentish-man in the

employ of the Virginia colony, led a naval expedition to the Bay of

Fundy and destroyed the Acadian settlements as an alleged infringement

of the Virginia charter. The region remained under British control until

1631, when Charles I, in order to persuade Louis XIII

to hand over the dowry long overdue on his Bourbon wife,

Henrietta-Maria, gave the Acadian lands (along with "Canada") back to

France. In the meantime, in 1621, Sir William Alexander, a Scottish

gentleman at the English court, had been given by James I a royal

warrant for the development of a great "New Scotland" here, by a company

of Scottish Adventurers. In the Latin text of the warrant, the

territory's name was rendered as "Nova Scotia," and this is about all of

the original enterprise that remains three and a half centuries later.

For a brief time, however, there was great promotional activity.

Alexander's notable book, Encouragement to Colonies, was

published in 1624; and in the same year an Order of Baronets of Nova

Scotia was instituted. Bands of colonists were sent out in 1628 and

1629-30.

In maps prepared by Sir William, many toponymical

details were worked out (on paper). "New Scotland" was subdivided into

two provinces: "New Caledonia" (the modern Nova Scotia, Prince Edward

Island and Southern Newfoundland) and "Alexandria" (after his own name),

consisting of our New Brunswick, Gaspésie and

Anticosti. Cape Breton Island became "New Galloway." Our modern St. John

River was named the "Clyde" and the St. Croix River the "Tweed."

appropriately separating "New Scotland" from "New England." Our Bay of

Fundy was named "Argall Bay." after the man who had destroyed the

Acadian Port Royal in 1613. The Bay of Chaleurs was to be the "Firth of

Forth." All this paper empire collapsed in 1631, when Charles I snatched

Sir William Alexander out of his new domain and handed it over to

France. It was reconquered in 1654 by a fleet from Cromwell's England

but was restored to France again in 1667 by an ever-obliging Charles

II: It came permanently to England in 1713 by

the Treaty of Utrecht. Sentimental modern Scots may day-dream over Sir

William's geographical terms that remained unimplemented by the course

of history.

TYPES OF SCOTTISH PLACE-NAMES IN CANADA

Scottish place-names in Canada are of five main

types:

(a) Actual place-names from Scotland, such as

Aberdeen, Argyle, Perth, Melrose.

(b) Such place-names with an added element, such as New Aberdeen,

Argyle Head, Perth Road, Melrose Hill.

(c) Scottish surnames, such as MacDonald, Currie, Duncan, Ferguson.

(d) Scottish surnames with an added element, such as MacDonald's

Corners, Currie Road, Duncan Cove, Ferguson's

Falls.

(e) New coinages, such as Skir Dhu ("Black Rock"), Loch Ban ("White

Lake"), and Beinn Breagh ("Beautiful Mountain").

FACTORS INFLUENCING CANADIAN TOPONYMY

For an immigrant toponymically this land, the size of

Europe, was not a a tabula rasa, ready for the imprint of new

names. For upwards of 30,000 years it had been occupied by a vast

network of aboriginal tribes, so diverse that 176 different Amerindian

languages are still recognized in Canada today. Every stream, lake, bay

headland and village already had its native name, and thousands of these

still survive, from Merigomish, Antigonish and Tatamagouche in the east,

through Quebec, Ottawa and Toronto, to Okanagan, Chilliwack, and Nanaimo

in the far west. While some of the largest lakes (such as Ontario, Erie,

Huron, Nipigon, Winnipeg, Manitoba and Winnipegosis) retain native

names, thousands of other lakes and rivers had their Indian names

calqued into English in the pioneer days. Virtually all of the famous

explorations of the land by the white man were actually guided by

Indians who already knew the terrain intimately and had access to its

languages.

Earlier than the Scots in much of Canada were the

French, and these as they settled staked out their own claims to the

naming of places and natural features. They total over six millions

today, and their towns provide a striking pageant of municipalized

saints - Sainte Anne de Beaupre, Sainte Anne de la Pocatiere, Sainte

Anne des Chenes, Sainte Anne des Monts, Sainte Anne des Plaines, Sainte

Anne du Lac, and all their sisters and brothers. Also competing with the

Scots in toponymic aggressiveness were the English and the Irish. In

Ontario, for example, the English-Canadians have their London (on the

Thames), Stratford (on the Avon), Bath, Brighton, Durham, Portsmouth,

Southampton, York and hundreds of others. In the same province, the

Irish-Canadians have townships named Cavan, Galway and Monaghan and

villages named Dublin, Enniskillen and Killarney. Nova Scotia has its

Londonderry and Alberta its Cork.

Also competing during recent decades for a place in

the toponymic sun are five million Canadians of European nationalities

other than British and French. Thus the Icelanders have given us Arnes,

Gimli and Hecla; the Hungarians Esterhazy and Bekevar; and the

Ukrainians (among scores of other place-names) Halicz, Sich, Julish and

Yasna Olana. The Scottish place-names in Canada have had to run the

gauntlet of a host of competitors.

In that struggle for survival, some of the more

rugged Scottish names have failed to acclimate themselves for Canadian

usage. We look in vain for Ecclefechan, Ardnamurchan, Sligachan and

Ballachulish. John Milton, in his Sonnet XI,

derided cacophonous Scottish surnames - "Gordon, Colkitto [i.e., G.

Coll ciotach, "Coll the left-handed or crafty"], or Mac-donnel, or

Galasp [i.e. Gillespie]. . . that would have made Quintilian stare and

gasp" - but three of the four have "grown sleek" to our mouths.

Pronounceability, however, has no doubt a bearing on viability.

Still another difficulty has sometimes lain in the

opposition of officialdom and its friends. The assigning of names to

territorial areas and post offices has been commonly in the hands of the

Establishment, which has been prompt to donate toponymic immortality to

politicians and their cronies. Scots from Prince Edward Island are ready

to tell of this sort of chicanery, especially along the east coast. Back

in the 1830s, in opening up what became Victoria County, Ontario, a

block settlement of Highlanders from Argyllshire and Islay wanted its

wholly Scotch township called "Caledonia," but the Family Compact

government in Toronto insisted on calling it "Eldon," after the lord

chancellor. One cannot get too indignant at this today, however, when

one discovers that the name "Caledonia" occurs six times in Canada,

three times in Nova Scotia, twice in Ontario, and once in Prince Edward

Island, all to the great confusion of postal clerks.

Since 1897, attempts have been made by the Federal

Government to achieve a tactful avoidance of so much duplication. A

"Canadian Permanent Committee on Geographical Names," with headquarters

in Ottawa, has been able, by discretionary consultation with the

provinces, to spread hundreds of totally new names across the Canadian

West in areas that were being opened up for the first time. There is no

"Caledonia" west of Ontario.

Notice may be taken of the wartime drive of public

emotion to change place-names. Thus, in 1824, "Berlin" was the

cheerfully accepted name for a city in Waterloo County, Ontario, an area

first settled in the early 1800's by Swiss-German immigrants from

Pennsylvania, later reinforced by settlers direct from Germany. In 1916,

however, under excited mass pressure from Ontario Anglo-Canadians, the

name was changed to "Kitchener", after Field Marshall Lord Kitchener,

who was drowned at sea in that year. Similar ultra-patriotic clamour

during World War II, demanding the suppression

of "Swastika" as the name of a community in the Timiskaming district of

Northern Ontario, was successfully blocked by the town's citizens, who

insisted that they had chosen the old folk-symbol as their municipal

name long before Hitler and his Nazis had adopted it as a political

trade-mark.

TOPONYMY AND DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGE

Even where a place-name may once have been happily

appropriate for a community, population changes may come to render it

meaningless. The tides of immigration ebb and flow, bringing totally new

racial stocks to the surface. A differential birth rate may serve to

replace one nationality by another. Canadians are a nomadic people,

streaming from the Prairies and the Maritimes to the affluent employment

centres of Ontario and Quebec, as well as from rural parts to the cities

in every province. We have suffered a hemorrhage of population to the

U.S.A. that runs to many millions. The total population of Canada is

almost equalled by the number of present-day Americans whose ancestors

(or themselves) once lived in Canada.

A number of instances will illustrate the story:

(a) "New Edinburgh,'' in Digby County, Nova Scotia,

was founded and its streets were carefully laid out in 1783 by a

Scottish U.E. Loyalist, Anthony Stewart, but demographic changes in the

area have made it an Acadian French fishing-village. Of its 40

telephones in 1968, some 39 were French (15 Doucets, 13 Amiraults, etc.)

and only one Scottish (a MacCormack).

(b) Shelburne, Nova Scotia, was founded in 1783 by

U.E. Loyalists, and by 1786, with a population of over 10,000, it was

the largest town in British North America. But the site was ill chosen,

storms swept away wharves and warehouses, free rations were cut off at

the end of 1786, the settlers fled to England, to Upper Canada, or even

back to the U.S.A., and by 1816, according to the Surveyor-General of

the province, only 374 persons were left in the town.

(c) In 1784, Preston, Nova Scotia, named by its

Scottish Loyalist founders after towns in the Lothians and Berwickshire

(unlike Preston, Ontario, which was named after Preston in Lancashire),

began its career as a toponymic transplantation from Scotland. In 1814,

however, it was used as a depot for Negroes rescued from slavery after

the burning of Washington, D.C.; and today the community is solidly

Negro.

(d) About 1773, a contingent of Scottish fisher-folk

settled along the south shore of the Restigouche River and its estuary,

and established such centres as Campbellton and Dawnsonville. Still

earlier, however, a flood of Acadians, returning in 1764 from the

deportations of 1755, settled on both shores of the Bay of Chaleurs. The

Acadians' greater numbers and greater prolificity have submerged the

Scottish communities and made them a small minority in a largely French

population.

(e) The same process of French replacement is well

advanced in the Eastern Townships of Quebec and in the famous old

Highland Scottish county of Glengarry.

(f) Colonsay and Saltcoats, shown as apparently

Scottish in my place-name list for Saskatchewan, have actually, since

1900-13, become Hungarian communities.

(g) In like manner, the seemingly Scottish towns of

Gretna (Manitoba) and Balgonie (Saskatchewan) are now almost completely

German.

Expansion rather than shrinkage of the Scots may be

noted in the case of Halifax, Nova Scotia. Founded by the English in

1749, and given a famous old Yorkshire name, it has so attracted

enterprising Scots from all parts of the Maritimes that its 1968

telephone directory listed 2400 "Macs," some 475 of whom were "Macdonalds."

Monuments to Burns and Scott dominate its public gardens and its "North

British Society" is perhaps the most powerful organization in the town.