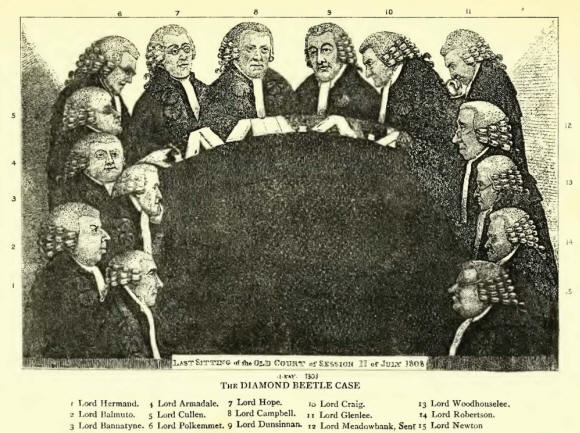

In the jeu d'esprit called the "Diamond Beetle

Case," attributed to George Cranstoun, Esq. (late Lord Corehouse), the

manner and professional peculiarities of several of the Senators

composing the "last sitting'' are happily imitated. The involved

phraseology of Lord Bannatyne—the predilection for Latin quotation of

Lord Meadow-bank—the brisk manner of Lord Hermand—the anti-Gallic

feeling of Lord Craig—the broad dialect of Lords Polkemmet and Balmuto—and

the hesitating manner of Lord Methven—are admirably caricatured. This

effusion, humorous without rancour, was much appreciated at the time,

and is so characteristic, that we need not apologise for giving it a

place here :—

"NOTES

TAKEN AT ADVISING THE ACTION OF DEFAMATION AND DAMAGES,

Alexander Cunningham, Jeweller in Edinburgh,

AGAINST

James Russell, Surgeon there.

"Lord President (Sir Ilay Campbell),—Your Lordships

have the petition of Alexander Cunningham against Lord Bannatyne's

interlocutor. It is a case of defamation and damages for calling the

petitioner's Diamond Beetle an Egyptian Louse. You have

the Lord Ordinary's distinct interlocutor on pages 29 and 30 of this

petition:— "Having considered the Condescendence of the pursuer, Answers

for 'defender,' and so on; Finds, in respect that it is not alleged that

' the diamonds on the back of the Diamond Beetle are real diamonds, or

anything but shining spots, such as are found on other Diamond' Beetles,

which likewise occur, though in a smaller number, on a great number of

other Beetles, somewhat different from the Beetle libelled, and similar

to which there may be Beetles in Egypt, with shining spots on their

backs, which may be termed Lice there, and may be different not only

from the common Louse, but from the Louse mentioned by Moses as one of

the plagues of Egypt, which is admitted to be a filthy troublesome

Louse, even worse than the said Louse, which is clearly different from

the Louse libelled. But that the other Louse is the same with, or

similar to, the said Beetle, which is also the same with the other

Beetle; and although different from the said Beetle libelled, yet as the

said Beetle is similar to the other Beetle, and the said Louse to the

said other Louse libelled; and the other Louse to the other Beetle,

which is the same with, or similar to, the Beetle, which somewhat

resembles the Beetle libelled; assoilzies the defender, and finds

expenses due.' "Say away, my Lords.

"Lord Meadowbank,—This is a very intricate and

puzzling question, my Lord. I have formed no decided opinion ; but at

present I am rather inclined to think the interlocutor is right, though

not upon the ratio assigned in it. It appears to me that there

are two points for consideration; First, Whether the words

libelled amount to a convicium; and, Secondly, Admitting

the convicium, whether the pursuer is entitled to found upon it

in this action. Now, my Lords, if there be a convicmm at all, it

consists in the comparatio or comparison of the Scarabceus

or Beetle with Egyptian Pediculus or Louse. My first doubt

regards this point, but it is not at all founded on what the defender

alleges, that there is no such animal as an Egyptian Pediculus or

Louse in rerum natura; for though it does not actually

exist, it may possibly exist; and whether its existence be in

esse vel posse, is the same thing to this question, provided

there be habiles for ascertaining what it would be if it did

exist. But my doubt is here. How am I to discover what are the

essentia of my Louse, whether Egyptian or not'? It is very easy to

describe its accidents as a naturalist would do—to say that it belongs

to the tribe of assterce (or that it is a yellow, little, greedy,

filthy, despicable reptile)—but we do not learn from this what the

proprium of the animal is in a logical sense, and still less what

its differentia are. Now, without these, it is impossible to

judge whether there is a convicium or not; for, in a case of this

kind, which sequitnr naturam delicti, we must take them

meliori sensu, and presume the comparatio to be in the

melioribus tantum. And here I beg that parties, and the bar in

general— [interrupted by Lord Hermand, Your Lordship should address

ijonrself to the Chair]—I say—I beg it may be understood that I do

not rest my opinion on the ground that Veritas convicii excusat.

I am clear that although this Beetle actually were an Egyptian

Pediculus, it would afford no relevant defence, provided the calling

it so were a convicium; and there my doubt lies.

"With regard to the second point, I am satisfied that

the Scarabceus or Beetle itself has no persona standi

injwdicio; and therefore the pursuer cannot insist in the name of

the Scarabceus, or for his behoof. If the action lie at all, it

must be at the instance of the pursuer himself, as the verus dominus

of the Scarabceus, for being calumniated through the

convicium directed primarily against the animal standing in that

relation to him. Now, abstracting from the qualification of an actual

dominium, which is not alleged, I have great doubts whether a mere

convicium is necessarily transmitted from one object to another,

through the relation of a dominium subsisting between them ; and,

if not necessarily transmissible, we must see the principle of its

actual transmission here ; and that has not yet been pointed out.

"Lord Heemand,—We heard a little ago, my Lord, that

there is a difficulty in this case ; but I have not been fortunate

enough, for my part, to find out where the difficulty lies. Will any man

presume to tell me that a Beetle is not a Beetle, and that a Louse is

not a Louse? I never saw the petitioner's Beetle; and what's more, I

don't care whether I ever see it or not; but I suppose it's like other

Beetles, and that's enough for me.

"But, my Lord, I know the other reptile well. I have

seen them, my Lord, ever since I was a child in my mother's arms ; and

my mind tells me that nothing but the deepest and blackest malice

rankling in the human breast could have suggested this comparison, or

led any man to form a thought so injurious and insulting. But, my Lord,

there's more here than all that—a great deal more. One could have

thought the defender would have gratified his spite to the full by

comparing the Beetle to a common Louse—an animal sufficiently vile and

abominable for the purpose of defamation-—[Shut that door there]—-but

he adds the epithet Egyptian, and I know well what he means by

that epithet. He means, my Lord, a Louse that has been fattened in the

head of a Oypsey or Tinker undisturbed by the comb, and

unmolested in the enjoyment of its native filth. He means a Louse ten

times larger, and ten times more abominable than those with which

your Lordships and I are familiar. The petitioner asks redress for

the injury, so atrocious and aggravated ; and, as far as my voice goes,

he shall not ask in vain.

"Lord Ceaig,—I am of the opinion last delivered. It

appears to me to be slanderous and calumnious to compare a Diamond

Beetle to the filthy and mischievous animal libelled. By an Egyptian

Louse, I understand one which has been formed in the head of a native

Egyptian—a race of men who, after degenerating for nianj' centuries,

have sunk at last into the abyss of depravity, in consequence of having

been subjugated for a time, by the French. I do not find that Turgot, or

Condorcet, or the rest of the economists, ever reckoned the combing of

the head a species of productive labour; and I conclude, therefore, that

wherever French principles have been propagated, Lice grow to an

immoderate size, especially in a warm climate like that of Egypt. I

shall only add, that we ought to be sensible of the blessings we

enjoy under a free and happy Constitution, where Lice and men live under

the restraint of equal laws—the only equality that can exist in a

well-regulated state.

"Lord Polkemmet,—It should be observed, my Lord, that

what is called a Beetle is a reptile well known in this country. I have

seen mony ane o'them in Drumshorlin Muir; it is a little black beastie,

about the size of my thoom nail. The country people ca' them Clocks ;

and, I believe, they ca' them also Maggy-wi'-the-mony-feet; but this is

not a beast like any Louse that ever I saw ; so that, iu my opinion,

though the defender may have made a blunder through ignorance, in

comparing them, there does not seem to have been any animus injur

i-audi: therefore I am for refusing the petition, my Lords.

"Lord Balmuto,—'Am for refusing the petition. There's

more Lice than Beetles in Fife. They ca' them Beetle-clocks there. "What

they ca' a Beetle, is a thing as lang as my arm; thick at the one end

and small at the other. I thought, when I read the petition, that the

Beetle or Bittle had been the thing that the women have when they are

washing towels or napery with—things for cladding them with; and I see

the petitioner is a jeweller till his trade; and I thought he had ane o'

thae Beetles, and set it all round with diamonds; and I thought it a

foolish and extravagant idea; and I saw no resemblance it could have to

a Louse. But I find I was mistaken, my Lord; and I find it only a

Beetle-clock the petitioner has ; but my opinion's the same it was

before. I saj% my Lords, 'am for refusing the petition, I say------

"Lord Woodhouselee,—There is a case abridged in the

third volume of the Dictionary of Decisions, Chalmers v. Douglas,

in which it was found, that Veritas convicii excusat, which may

be rendered not literally, but in a free and spirited manner, according

to the most approved principles of translation, 'the truth of calumnj'

affords a relevant defence.' If, therefore, it be the law of Scotland

(which I am clearly of opinion it is), that the truth of the calumny

affords a relevant defence—and if it be likewise true, that the Diamond

Beetle is really an Egyptian Louse—I am inclined to conclude (though

certainly the case is attended with difficulty) that the defender ought

to be assolzied.—Refuse.

"Lord Justice Clerk (Rae),—I am very well acqainted

with the defender in this action, and have respect for him—and esteem

him likewise. I know him to be a skilful and expert surgeon, and also a

good man; and I would go a great length to serve him, if I had it my

power to do so. But I think on this occasion he has spoken rashly, and I

fear foolishly and improperly. I hope he had no bad intention —I am sure

he had not. But the petitioner (for whom I have likewise a great

respect, because I knew his father, who was a very respectable baker in

Edinburgh, and supplied my family with bread, and very good bread it

was, and for which his accounts were regularly discharged), it seems has

a Clock or a Beetle, I think it is called a Diamond Beetle, which he is

very fond of, and has a fancy for, and the defender has compared it to a

Louse, or a Bug, or a Flea, or something of that kind, with a view to

render it despicable or ridiculous, and the petitioner so likewise, as

the proprietor or owner thereof. It is said that this is a Louse in

fact, and that the Veritas convicii excusat; and mention is

made of a decision in the case of Chalmers v. Douglas. I have

always had a great veneration for the decisions of your Lordships : and

I am sure will always continue to have while I sit here ; but that case

was determined by a very small majority, and I have heard your Lordships

mention it on various occasions, and you have always desiderated the

propriety of it, and I think have departed from it in some instances. I

remember the circumstances of the case well:—Helen Chalmers lived in

Musselburgh, and the defender, Mrs. Baillie, lived in Fisherrow; and at

that time there was much intercourse between the genteel inhabitants of

Fisherrow, and Musselburgh, and Inveresk, and likewise Newbigging; and

there were balls, or dances, or assemblies, every fortnight, or oftener,

and also sometimes I believe every week ; and there were card-parties,

assemblies once a fortnight, or oftener; and the young people danced

there also, and others played at cards, and there were various

refreshments, such as tea and coffee, and butter and bread, and I

believe, but I am not sure, porter and negus, and likewise small beer.

And it was at one of these assemblies that Mrs. Baillie called Mrs.

Chalmers a------, or an---------, and said she had been lying with

Commissioner Cardonald, a gentleman whom I knew very well at one time,

and had a great respect for. He is dead many years ago. And Mrs.

Chalmers brought an action of defamation before the Commissaries, and it

came by advocation into this Court, and your Lordships allowed a proof

of the Veritas convicii, and it lasted a very long time, and in

the end answered no good purpose even to the defender herself, while it

did much hurt to the pursuer's character. I am therefore for refusing a

proof in this case ; and I think the petitioner in this case and his

Beetle have been slandered, and the petition ought to be seen.

"Lord Methven,—If I understand this

a—a—a—interlocutor, it is not said that the a—a—a—a—Egyptian Lice are

Beetles, but that they may be, or —a—a—-a—-a resemble Beetles. I am

therefore for sending the process to the Ordinary to ascertain the fact,

as I think it depends upon that whether there be a—a—a—a—coiivicium

or not. I think also the petitioner should be ordained to

a—a—a—produce his Beetle, and the defender an Egyptian Louse or

Pedicalns, and that he should take a diligence a—a—a—to recover Lice

of various kinds ; and these may be remitted to Dr. Monro, or Mr.

Playfair, or to some other naturalist, to report upon the subject.

"Agreed to."