|

Fourth Report of the boar& of supervision — Occurrence of cholera —

Fifth and sixth Reports — Distress in the Highlands and Islands; Sir

John McNeill's Report — "Crofters," "Tacksmen," "Tenants," and "Cottars"

— Kelp manufacture — Results of the Croft and Cottar system — Emigration

the only remedy— Administration of relief in the western districts —

Seventh and eighth Reports --- Sir John McNeill's Reports on Caithness,

and on the free and pauper colonies in Holland — Divergence between the

English and Scottish systems of relief — Present practice in Scotland

—Approximation of the Scottish and English systems—Conclusion.

The fourth Report, like

those preceding, is dated in August, and is arranged in similar order.

The elections are said to have been everywhere conducted satisfactorily,

and "to have terminated without litigation, except in the city parish of

Glasgow, where the contest was unusually keen." The commissioners had

deputed two of their officers to inquire into the proceedings of the

inspectors, and the condition and management of the poor in certain

urban, suburban, and other parishes; and the Reports of these officers,

although for the most part favourable, yet brought to light some defects

and abuses which are said to have been corrected, and which it is hoped

would not again occur.

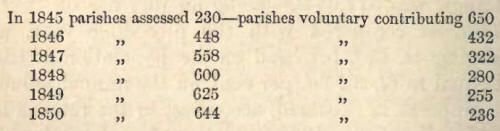

Since the last Report, 23

parishes which had raised the funds for relief of the poor by voluntary

contributions, resolved to raise these funds by assessment. The number

of parishes now assessed was therefore 625, and the number unassessed

255. Twenty-four parishes resolved to change the mode of assessment or

the classification previously adopted, and in 20 the proposed change was

sanctioned, but in 4 the sanction was withheld. In two parishes, the

commissioners say, the discussions which arose about changing the mode

of assessment between persons interested in real property on one side,

and the rest of the ratepayers on the other, have led to dissensions in

the parochial boards. Differences of opinion, it is remarked "are

natural and perhaps inevitable, when questions affecting different

interests are discussed by popular bodies representing those interests

;" but regret is expressed that the discussions in these two parochial

boards should have been conducted in a manner not calculated to promote

harmony amongst the ratepayers, or to facilitate the administration of

the law. Plans and

specifications for the erection of three new poorhouses had been

approved. The number of inmates which these houses were calculated to

accommodate was 1,974, and the population of the six parishes for which

they were intended was 141,082, so that there would be poorhouse

accommodation in these parishes for 1 in 71 of their population. A table

is appended showing that the available poorhouse accommodation in

Scotland, either permanent or temporary, was adapted for 4,360 persons

at the date of the Report; and that when the plans which had been

sanctioned were all completed, there would be room for 2,728 more,

making altogether poorhouse accommodation for 7,088 inmates, out of a

population of 693,558, which is equal to 1 in 97.82 of the inhabitants.

The parliamentary grant (10,000l.) in

aid of medical relief in Scotland, was distributed in conformity with

the plan described in the preceding Report. 53 5 parishes resolved to

comply with the prescribed conditions, but of these only 438 established

their claim to participate in the grant by proving the required

expenditure from their own funds. The commissioners remark, that the

medical relief of the poor which was formerly hardly recognised as a

duty, had since the new law came into operation continued to increase in

efficiency, and with the aid of the parliamentary grant may now, they

hope, be placed on a satisfactory footing. The expenditure for this

purpose in the present year amounted to 33,010l. 12s.11 d., or

2,671l. above what it was returned as being last year; but as

nutritious diet and other matters are supposed to have been included in

that year's expenditure, and as everything not strictly appertaining to

medical relief has been carefully excluded in the present, the increase

has probably been far greater than the above figures indicate. Five

years ago this description of relief was provided in a few parishes

only, and it must therefore be admitted that considerable progress has

been now made towards remedying the deficiency. There are still however

many parishes in which medical relief is said to be very imperfectly

administered, and few in which it is administered with the regularity

that it ought to be, and that it might be without entailing additional

cost; and the commissioners express a confident expectation that "they

shall have the ready co-operation of a great majority of the parochial

boards, in carrying out the rules by which it has been endeavoured to

give more uniformity and regularity to the system, and to place its

administration under such checks as may afford the parochial authorities

and the public a reasonable security that the duty is adequately

performed." In

connexion with medical relief, it is necessary to state that cases of

malignant cholera occurred in Edinburgh early in October 1848, and the

commissioners thereupon made application to the general board of health

for the directions which that board was empowered by the 11th and 12th

Vict., cap. 123, to issue, "for the prevention as far as possible or

mitigation of epidemic, endemic, or contagious diseases." But without

waiting for the receipt of such directions, a circular was addressed to

the several parochial boards calling their attention to the 69t/i

section of the Amendment Act, by which they are required out of the

funds raised for the relief of the poor, to provide medicines medical

attendance, nutritious diet and cordials for the sick, and pointing out

the necessity of their providing for the proper medical treatment "of

all poor persons suffering from symptoms indicating the probable

approach or presence of cholera." If their ordinary means were not

sufficient, they are recommended to increase them forthwith, the

necessity for immediate relief in cases of cholera being too urgent to

admit of delay. The relief necessary to preserve life must, it is said,

be promptly given—the inquiries as to the right to demand it, may be

made afterwards. As

soon as the directions of the board of health were received, copies of

these directions were forwarded to all the parochial boards, together

with suggestions in reference to the duties required from them. A great

responsibility they were told devolved upon the parochial boards, "who

are bound if other parties fail in performing their duties, to see that

none of the directions issued by the board of health are left

unperformed." The formidable scourge appeared first in Edinburgh, but it

soon spread to the neighbouring towns, and early in November it reached

Glasgow, and the manufacturing towns and villages in the south and west

of Scotland. In Dumfries the disease burst forth with great violence,

269 deaths from cholera having occurred there within a month after its

first appearance. At Glasgow the deaths from cholera in one week

amounted to 829. "During the height of the epidemic indeed, all Glasgow

appears to have been affected." d Edinburgh suffered less severely,

although it was first visited, the deaths from cholera recorded there

(including Leith and Newhaven) from the commencement to the 18th of June

following, amounted to 554. The disease appears to have subsided in the

spring, but during the summer and autumn of 1849, it again assumed its

former virulence, attacking most of the principal towns, as well as

certain other localities both in England and Scotland.

The first great outburst of cholera occurred

in India in 1817, and after raging there with fearful virulence for some

time, it extended its ravages over nearly all the rest of the world. In

each of its subsequent visitations, in that of 1831-2 as well as in the

present 1848-9, the cholera also appears to have commenced or had its

origin in India, whence it travelled westward by successive and

well-ascertained stages. On this latter occasion it made its appearance

first at Caubul in 1845. Bombay, Kurrachee and Scinde were attacked in

1846. Afterwards the epidemic extended over Persia and Syria, reaching

Astrakhan at the mouth of the Volga in June, and Moscow in September

1847, Petersburgh and Berlin in June 1848, Hamburgh in September, and

Edinburgh in the beginning of October. On this last occasion the

epidemic travelled at the same rate, and by almost precisely the same

route as in 1831-2. Its effects in the two instances of Glasgow and

Dumfries are noticed above, but there are no means of ascertaining the

number of deaths from cholera in the whole of Scotland. This can however

be done with respect to England through the Registrar-General's Reports,

by which it appears that in London above 14,137 persons died of cholera

in 1849, and that the deaths from cholera throughout England and Wales

in that year amounted to 53,293,—"The decline of the epidemic was more

rapid than its increase. While it was fatal to 20,379 in September,

4,654 died of it in October, 844 in November, and 163 in December."

The pestilence has been far more fatal on this than it was on the former

occasion, the deaths in 1831-2 amounting to 30,924, whilst in 1848-9 the

deaths amounted to 54,398.

This notice of the effects of the cholera in

England, may assist in estimating the effects of the epidemic in

Scotland. In both countries these effects are closely connected with the

condition of the people, and have an important bearing on Poor Law

administration, not only as regards the relief of the poor, but likewise

with regard to the sanitary measures, for the due execution of which the

Poor Law functionaries are under the Nuisances Removal Act made

responsible. The

season under consideration was one of great pressure and difficulty. The

high price of food, a near approach to actual famine in some districts

through the failure of the potato, the stagnation of trade, the dearth

of employment, and the spread of pestilence—all pressing at one time,

seem enough to have embarrassed the resources and paralysed the energies

of the country. But happily the several parts of our social fabric hang

so well together, its gradations are so harmoniously adjusted, and

afford such mutual support, each upholding and assisting the other, that

events which would almost cause the disruption of society under other

circumstances, are here sustained with comparatively little difficulty;

and as soon as the season of trial or privation has passed, the efforts

and the sacrifices which it exacted are no longer thought of, and the

marks of the visitation melt away and disappear before the combined

exertions of a free and united people.

The Report states that the number of

applications complaining of inadequate relief during the year amounted

to 863, of which complaints, 447 were dismissed on the information

contained in the schedules, and after being referred to parochial

boards. In 256 cases remitted to the parochial boards, the grounds of

complaint were removed; and in 4 cases, the ground of complaint not

having been removed, the commissioners issued minutes declaring that the

complainants had just ground of action against their respective parishes

in the court of session. Of the 863 cases submitted to the

commissioners, there remained only one, they say, undisposed of, a

circumstance highly creditable to their zeal and industry.

The applications in the sheriffs' courts

during the year ending 30th June 1849, under the 73rd, 79th and 80th

sections of the Amendment Act, amounted to 1,198. Of the whole number of

cases in which the claims of persons applying for relief were resisted,

a final order in the applicant's favour was made in 251, while out of

'72 cases in which answers were lodged, 426 were either dismissed on the

merits, or abandoned by the applicants themselves. As poorhouses

increase in, the different districts, they will, it is observed,

"furnish parochial boards with a simple method of testing all cases in

which there is reason to doubt the disability or the destitution of

applicants for relief," and a confident hope is then expressed " that

much of the expense of litigation will thus be saved to the parochial

boards, and that the sheriffs will at the same time be relieved to a

great extent of what is to them at present a most troublesome and

anxious duty." The

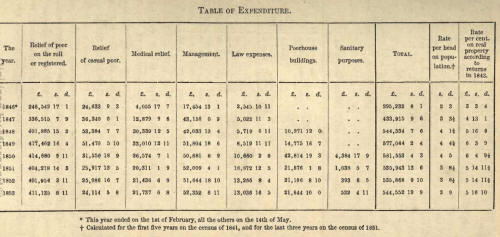

amount expended on the relief and management of the poor for the year

ending 14th May 1849, including 14,775l. expended on poorhouse

buildings, was 577,044l.—being an increase of 32,710l. as

compared with the preceding year, and averaging 4s. 4d. per head on the

population of 1841, and equal to 6l. 3s. 9d. per cent. on the

annual value of real property in Scotland, according to the returns laid

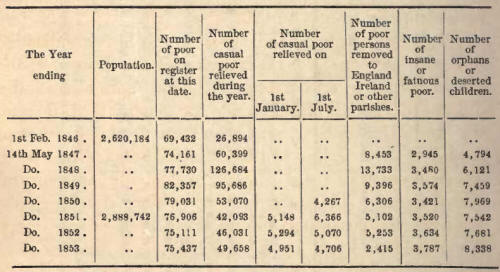

before parliament in 1843. The number of regular poor on the roll on the

14th May 1849 was 82357—being 1 in 31.8 of the population; and the

number of casual poor relieved in the year, was 95,686. While the number

of regular poor has thus increased, the casual poor have we see sensibly

diminished in the present year, as compared with the last; but this

diminution has chiefly arisen from there having been a smaller number of

immigrants from Ireland.

The fifth Report makes no

mention of the elections, and they may therefore be presumed to have

been properly conducted, as was for the most part the. case in preceding

years. The commissioners considered it necessary to send one of their

officers to inquire into the condition and management of the poor in the

county of Galloway, and the result was they say, on the whole

satisfactory, although abuses requiring to be redressed were discovered

in some of the parishes.

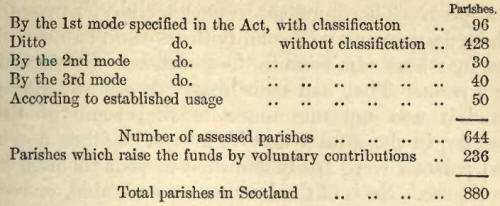

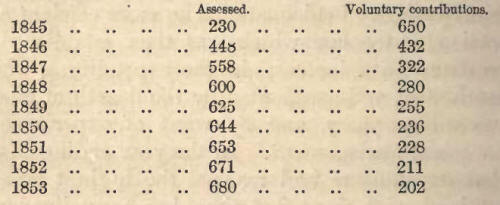

Of the parishes which previously raised

their funds for relief of the poor by voluntary contributions, 19 had,

since the date of the last Report, resolved to raise those funds by

assessment. The parishes assessed therefore, now amounted to 644, and

the number that raised the funds by voluntary contributions to 236. In

21 parishes the parochial boards resolved to change the mode of

assessment or classification formerly adopted, 13 of which changes were

sanctioned by the commissioners, but in 7 the sanction was refused, and

one was still undecided.

The progressive change from voluntary

contributions to assessment, during the five years since the amended law

came into operation, has been as follows-

The funds for the relief of the poor in the

several parishes were raised in the following manner---

The plans and specification for one

additional poor-house only had been approved in the present year, but it

was for a combination of ten parishes, with an aggregate population of

23,133, and was calculated for 362 inmates, so there would be poorhouse

accommodation for one in 64 of the population. The several parochial

boards had been called upon to frame regulations for the management of

their respective poorhouses, in conformity with the 64th section of the

Act; but these, were found to be for the most part so defective, that

the commissioners determined to frame such a complete set of rules and

regulations for adoption by the parochial boards, as would secure

uniformity and efficiency in this highly important. part of parochial

management. These regulations had, it is said, with slight adaptations

to local peculiantics in a few instances, been generally adopted, and

were then in force. They conform very closely to the English workhouse

regulations, and in transmitting them to the parishes having poorhouses,

the cornmissioners addressed a letter to the parochial boards, pointing

out the objects and the importance of these institutions under the new

law, and the altered circumstances of the times in which they were to be

applied. So long, it is said, as relief to the poor was looked upon as

the fulfilment of a charitable rather than a legal obligation,

poorhouses were naturally regarded in the light of almshouses for the

reception of the infirm or friendless poor. The inmates were generally

persons of whose destitution and disability there could be no doubt.,

and by whom admission to the poorhouse was regarded as a boon. They had

their liberty days once a week, "and it was not uncommon to find some of

them begging in the streets and highways." Once a week also persons were

freely admitted to visit them in the poorhouse. Such of the inmates as

were able, or could be induced to engage in any industrial occupation,

received a weekly payment for their work, which they spent as they liked

on their liberty days; "and one of the first petitions presented to the

board of supervision was from the male inmates of a poorhouse,

complaining that the weekly sum allowed them as pocket-money was

unreasonably small."

Under such circumstances it was, the

commissioners observe, unnecessary to establish strict regulations in

the poorhouses, as any misconduct might be punished by expulsion. But

poorhouses must now, it is said, be prepared to receive a new and wholly

different class of inmates—"The altered feelings of the poor in regard

to parochial relief, their more perfect knowledge` of their rights, and

the facilities which the law now affords for enforcing them, have caused

a strong pressure upon parochial boards from a class whose claims it

would be unsafe to admit, without testing the truth of the allegations

on which they are founded." For this purpose a well-regulated poorhouse

is declared to be the best of all tests—"while it furnishes sufficient,

and even ample relief to the really necessitous, it affords the only

available security that the funds raised for the relief of the poor are

not perverted to the maintenance of idleness and vice." But a poorhouse

will, it is added, "be wholly useless as a test, or rather it will not

be a test at all, unless it is conducted under rules and regulations as

to discipline and restraint, so as to render it more irksome than labour

to those who are not truly fit objects of parochial relief." This is so

complete an exposition of the workhouse principle, as recognised and

practised in England, that I give it in the commissioners' own words, in

order to show more clearly the advance founded on experience, the surest

of all guides, which had been made in poor-law administration in

Scotland during the preceding five or six years.

The proper objects for admission to a

poorhouse are described as being of two classes—First all destitute

persons incapacitated by youth or old age or by disease, whether mental

or physical, from contributing in any way to their own support; and who

from being friendless, or weak in mind, or from requiring more than

ordinary attendance, cannot be adequately maintained and cared for by

means of out-door relief, except at a cost exceeding that for which they

can be maintained in the poorhouse. Secondly, all persons applying for

or receiving relief whose claims are doubtful, such as persons suspected

of concealing or misrepresenting their means and resources, or persons

who although not able-bodied, are yet not so disabled as to be incapable

of maintaining themselves; but more especially all persons of idle

immoral or dissipated habits, who if allowed out-door relief would

squander it in drunkenness and debauchery, or otherwise misapply it—For

all such, the poorhouse is held to afford the fittest means of relief.

Poor persons, it is added, "may not be allowed to starve, because they

or their parents are vicious; but the law leaves to the bodies to whom

its administration is entrusted, a choice as to the manner of affording

relief; and if parochial boards desire. to discourage indolence, to

detect imposture, to check extravagance, and to reform or control vice,

they must make work, confinement, and discipline, the conditions upon

which paupers of this class are relieved."

For persons not comprised in. one or the

other of the above two classes, the commissioners are of opinion that it

will be more to the advantage both of such persons and of the parish,

that they should be furnished with out-door relief; "for any systematic

attempt to refuse all relief except to such as may be relieved within

the walls of a poorhouse would, they say, excite a baneful spirit of

discontent amongst the poor and that part of the population with which

they are most closely connected, without effecting any saving to the

funds of the parish; and far from being countenanced, would scarcely be

tolerated by public opinion in this country." The commissioners are

probably right as to the state of feeling in Scotland on this point, and

it might not have been then expedient to press the subject further ; but

it seems clear that the principle which they have with so much force and

truth laid down in their instructional letter, must eventually, and

perhaps at no distant day, lead to the unrestricted use of the

poorhouse, without specific preference or exception of any particular

class, although poorhouse relief may not be applied in every case, nor

its acceptance be universally made a condition on which any relief

whatever should be afforded.

The arrangements for distributing the

parliamentary grant in aid of medical relief, are said to have worked

satisfactorily. 569 parishes had resolved to comply with the required

conditions, but of these only 498 established their claims to

participate in the grant by furnishing the necessary amount of

expenditure from their own resources. The sum returned as being expended

on medical relief in the current year, was 26,574l. 7s.

With respect to insane and fatuous paupers,

returns had been received, accompanied by medical -certificates, of all

those whose removal to an asylum had been dispensed with; and all the

new cases reported, as well as those in which the medical certificates

annexed to subsequent returns did not appear satisfactory, had been

investigated. In 141 new cases the commissioners dispensed with removal,

and in two cases they required that the lunatics should be placed in an

asylum. A considerable number of pauper lunatics, mostly fatuous and

harmless, were now, it appears, kept in the different poorhouses, and

the commissioners are of opinion that for such persons a well-regulated

poorhouse is the best place of refuge. Not only, they say, is the cost

of maintaining such persons in a poorhouse less than half what it would

be in an asylum, but if all the pauper lunatics were to be placed in

asylums, the whole of the accommodation it would be practicable to

provide, would be occupied by a continually accumulating number of

incurables, and the difficulty of obtaining admission for recent and

curable cases would be greater even than it is at present. There are,

the commissioners observe, certain legal objections to placing harmless

pauper lunatics in poorhouses, which might however be overcome by

obtaining licences for these establishments; but if this were done, it

may be feared that some of the parochial boards would, on the score of

convenience and economy, be induced to place in the poorhouses lunatics

susceptible of cure, and who ought to be sent to an asylum. The

commissioners have they say no authority in the matter; "but the

sheriffs of counties, without whose licence no lunatic can legally be

detained, are vested with power to determine this question in each case,

and can require that any lunatic for whom a licence is granted, shall be

placed in an asylum and not in a licensed house."

The number of complaints of inadequate

relief made to the board of supervision in the year amounted to 788, of

which 439 were dismissed on the information appended to the schedules of

complaint, and 97 after reference to parochial boards. In 114 cases the

parochial boards removed, the ground of complaint, but in two cases, the

ground of complaint not being so removed, the commissioners issued

minutes in the terms of the Act, declaring that the applicants had just

cause of action against their parish in the court of session. No case,

it is said, remains undisposed of; and upon the whole, with reference to

these applications and complaints, the commissioners regard the results

of the past year "as exhibiting a marked improvement, not only as

showing a decrease in the number of . applications, but as evincing a

jester exercise of discretion on the part of relieving officers, in

dealing with those demands upon the parochial funds which seemed either

groundless or unreasonable."

The returns of the applications made in the

sheriffs' courts in the present year by persons refused relief, show

that they amounted to 739. In 389 of these cases, answers in resistance

of the claims were lodged on the part of the parochial boards. The

number of cases in which the applications were either dismissed by the

court on the merits, or abandoned by the parties themselves, is stated

to have been 332; so that the resistance made to the claims for relief

appears to have been successful in 314 out of 389 cases, and to have

been unsuccessful in 75.

The amount expended on the relief and

management of the poor in the year ended 14th. May 1850, was 538,738l.

5s. 0½d.; to which must be added for expenditure on poorhouse buildings

42,814l. 19s. 3d., making a total expenditure of 581,553l.

4s. 3½d. The number of regular poor on the roll on the 14th of May 1850,

was 79,031—being 1 in 33.15 of the population; and the number of casual

poor relieved in the year, was 53,070. Many of the casual poor are

however said to be relieved more than once in the same parish, and

sometimes repeatedly in several different parishes. Persons moreover who

are subsequently relieved by order of the parochial board, are in/the

first instance relieved temporarily by the inspector, without such

order; so that the numbers of the casual poor given in the returns,

represent the number of successful applications to the inspector for

temporary aid, rather than the number effectually relieved. The total

number of casual poor and vagrants relieved on the 1st of July 1850, was

4,267, of whom 1,542 were males, and 2,725 were females. By adding these

to the regular poor on the roll on the 14th of Alay, it will appear that

the number of persons receiving relief at one time in one of the summer

months was 83,298, or 1 in 31.40 of the population, according to the

census of 1841. It

appears from the foregoing statements, that there was a continual

increase in the expenditure, as well as in the numbers relieved, until

towards the end of the present year, when a decrease took place in both,

especially in the number of casual poor. 9 This result the commissioners

consider to be highly satisfactory, not only as indicating improvement

in the condition of the working classes, but also as being calculated to

allay the apprehensions excited by a continual increase of expenditure,

and in the number of the poor seeking relief, during several preceding

years. It likewise, the commissioners consider, affords ground for

believing, that while the late Act was designed and has tended to

increase the amount of relief, and to facilitate the means of obtaining

it, the administration established by that Act has been able to regulate

such tendency, and to adjust the expenditure to the actual necessities

of the poor. The establishment of well-conducted poorhouses will, the

commissioners add, contribute materially to confirm this power of

regulating expenditure, without injustice to the poor; and they express

a hope "that experience and observation of the many advantages derived

from possessing the means of affording relief in this form, not only in

urban but also in rural parishes, will lead to the erection of a greater

number of such houses, notwithstanding the present reduction in the

expenditure." The

sixth Report of the board of supervision is dated August 1851. Since the

last Report, 9 parishes which had previously raised the funds for relief

of the poor by voluntary contributions, have resorted to assessment. The

number of assessed parishes was now therefore 653, and the number

unassessed 228, the total number of parishes having been increased to

881, instead of 880, by Firth and Stennis in Orkney which were formerly

considered one parish, being declared separate parishes for poor-law

purposes. Of the 653 parishes at this time assessed, there were only 79

which assess "means and substance."

Plans for the erection of two poorhouses,

and for the enlargement of others, were approved. Six parishes,

containing a population of 8,814, have agreed to combine for the purpose

of providing a poorhouse with accommodation for 80 inmates; and two

other parishes, having together a population of 7,798, also agreed to

combine for a like purpose; but after the arrangements were nearly

completed, and the plans prepared, one of them withdrew, and the measure

was therefore abandoned, at least for the present. In addition to the

parishes which had provided or resolved to provide poorhouses for

themselves, there were 48 other parishes, with a population of 289,048,

which had made arrangements for placing their paupers in neighbouring

poorhouses, under the 65th section of the Amendment Act; and the

commissioners remark, that "the total population to which poorhouse

accommodation for paupers is now more or less available, amounts to

1,062,993, or nearly 2-5 the of the entire population of Scotland."

In the current year, 508 parishes appear to

have established their claim to participate in the Medial parliamentary

grant in aid of medical relief. relief. The entire sum expended in this

species of relief was 20,3111. is. 9d. The population of the parishes

which complied with the conditions entitling them to participate in the

grant was 2,071,478, and of the parishes that had not so complied

548,706. The expenditure on medical relief by the former was 17,257l:

16s. 11d., being about 2d. per head on the population, and by the latter

it was 3,053l. 5s. 8 d., equal to about 11d. per head on the

population. The parliamentary grant seems therefore, in accordance with

the benevolent intentions of the legislature, to have led to a more

liberal administration of medical relief.

The number of applications to the board of

supervision in the present year complaining of inadequate relief was

764, of which number 472 were dismissed on the information contained in

the schedules, and 72 were dismissed after being remitted to the

parochial boards for explanation; in 184 the ground of complaint was

removed, and in 3 cases minutes were issued declaring that the

complainants had just cause of action against their parishes.

The returns of applications on account of

the refusal of relief, continued to exhibit a progressive decrease in

the number of those cases to which the jurisdiction of the sheriffs

extends, as compared with the returns of former years. After pointing

out certain discrepancies in preceding returns, the commissioners

observe—"When we look at the number of cases in which an order was made

by the sheriff for interim relief, which we consider to be an index of

the cases calling for the sheriff's intervention, far more to be relied

on than the number of applications made, the real decrease is apparent.

We find a reduction from 739 to 539, being somewhat more than one-fourth

of the whole number." There is a like diminution under all the other

heads of the return, and the general result is considered to be very

favourable, as affording indications of the satisfactory working of the

law. The decrease

of expenditure on account of the relief of the poor, which for the first

time the commissioners had last year the satisfaction of reporting,

still continued, the entire amount expended in the present year,

including 21,576l. 1s. 8d. for poorhouse buildings, being 535,943l.

13s. 6d., whilst the number of regular poor on the roll on the 14th of

May was 76,906 and the number of casual poor relieved in the year was

42,093. The number of casual poor and vagrants relieved on the 1st of

January and 1st of July respectively in the present year (1851), has

been 5,148 and 6,366. On the 1st of July in the preceding year the

number of such persons relieved was 4,267. While the number of casual

poor relieved throughout the year has thus been considerably less than

in the last, the numbers relieved on each of the two days for which the

returns were made, have we see considerably increased. The increase is

said "to be chiefly attributable to the distress prevailing in some

districts of the Highlands and Islands, and to the temporary relief

there afforded to destitute able-bodied persons who are classed as

casual poor." In

consequence of the distress in the Highlands and Islands above noticed,

and which had prevailed with greater or less intensity since 1846,h the

board of supervision were directed by government to cause an examination

to be made into the state of those districts, and to report on "the

means of rendering the local resources available for the relief of the

inhabitants." The chairman of the board undertook the investigation, on

which he was engaged from the beginning of February to the middle of

April; and the results of his inquiry were embodied in a comprehensive

Report, to the most prominent portions of which we will now advert.

The first step taken on all occasions

throughout the inquiry, Sir John McNeill observes, was to call a meeting

of the parochial boards, which consisted everywhere of the most

intelligent persons of the district, and to explain to them that the

object sought for was the application of local resources, and not the

providing of extraneous aid. Their attention was " directed to the

obligation imposed upon them by the statute, to give adequate relief to

all disabled and destitute persons who apply for it, and to the

necessary consequence, that destitute persons who, from want of

sufficient food, ceased to be able-bodied, had a right to relief." They

were told, that although the recent Act did not give able-bodied persons

out of employment a right to relief, it gave to parochial boards a

discretionary power to afford temporary relief to casual poor, including

able-bodied persons in absolute want; and that viewed merely as a

question of economy, it was well for them to consider whether it might

not be more advantageous to give temporary aid to such able-bodied

persons, than to withhold it until disablement arises through the

pressure of absolute want. The discretion with which they are invested

would, they were told, afford the means in any emergency of applying

their local resources to the temporary relief of destitution, however

arising; "but it was for them to determine in what manner they would use

that power, the exercise of which was left entirely to their own

discretion." The

inquiry included a portion of the mainland, and extended to the islands

of Mull, Skye, Lewis, Uist, Harris, Long Island, Barra, Tyree, and Coll.

Sir John McNeill bears testimony to. the, uniform civility and good

conduct of the working classes in all the places he visited, and this

under circumstances calculated to excite feelings of disappointment; for

they appear, he says, to have formed exaggerated notions as to their

right, under the new Poor Law, of being provided with employment and the

means of subsistence at home, without being compelled to seek for either

elsewhere. They believed that they were legally entitled to the aid they

had been annually receiving from the destitution fund and other sources

since 1846, and its continuance was confidently reckoned on in the

present year. If all else failed, they thought the government, which had

hitherto they said done nothing for the Highlanders, 44 could not refuse

to provide the comparatively small amount of assistance they required,

when so vast an amount had been given to Ireland." Everything he had to

state on these points, was calculated to disappoint the expectations of

the people, yet he remarks —I did not anywhere observe a tone, a look,

or a gesture, that indicated resentment or irritation. They frequently

argued freely, sometimes with considerable ability and subtlety, never

with rudeness, and often with a politeness and delicacy of deportment

that would have been graceful in any society, and such as perhaps no men

of their class, in any other country I am acquainted with, could have

maintained in similar circumstances. Many went away dejected, but none

without some parting expressions of personal kindness and obligation."

The first point to be ascertained was,

whether any distress existed or was likely to arise, so urgent and

extreme as to require assistance beyond what the local resources could

supply. The alarm of famine appeared to be general, and a belief

everywhere prevailed that many persons had perished from want of food,

and that the relief which had been derived from the destitution fund

during the'fout4receding years continued to be still necessary. But on

the other hand, the condition of the inhabitants in regard to health was

seen to be generally good, and not to indicate suffering from want,

although such relief had now been delayed considerably beyond the usual

period. This seemed an important fact, and was deemed to be satisfactory

as regards the present state of the population; and with respect to the

future, it was ascertained that all the parochial boards had authorised

the inspectors "to afford temporary relief iii urgent cases to persons

not entitled by law to demand it"—in fact the parochial boards in the

islands had, it is said, "begun to exercise their discretionary power to

give temporary relief to able-bodied persons in absolute want, from the

commencement of the distress in 1846; had suspended that description of

relief while the destitution fund was in operation; and had

spontaneously resumed it, on a limited scale, when the fund was

understood to be exhausted." The authority which was thus given to the

inspectors, made them responsible for the due administration of relief

in every case. They were liable to be proceeded against criminally, if

from failing to afford "needful sustentation," they allowed any fit

object of parochial relief to perish for want of food; and this

liability would, in the ordinary course of law, operate as a protection

to the poor, and prevent the occurrence of such a painful contingency,

although instances of severe distress might not be altogether prevented.

With the advance of the season and the

exhaustion of the last year's crop, the number of persons requiring

relief would be certain to increase; but it was by no means certain that

many of these persons might not. maintain themselves by employment

elsewhere, and which employment they would probably have sought after,

but for the expectation of finding relief of some kind or in some way at

home. The means of employment in the western districts, is generally

insufficient for the maintenance of the inhabitants throughout the year,

and distress in some part of it must therefore be regarded as the

natural condition of the people, to be remedied only by a decrease in

their number, or by an increase in the means of employment; but both the

remedies are attended with difficulty. The population of these districts

chiefly consists of three classes, each holding land directly from the

proprietor. The 'Crofters' are persons occupying lands at a rental not

exceeding 20l. a year, and are by far the most numerous class.

The ' Tacksmen' have leases or `tacks' generally paying a rent exceeding

50l. a year, and in point of circumstances are the most

considerable of all the classes. Intermediate between these is another

class paying rent of from 20l. to 50l., and who not having

leases are not 'Tacksmen,' and not liking to be classed with the

`Crofters,' are called 'Tenants.' Besides these three classes, who hold

land directly from the proprietor, there is another called Cottars,' who

are numerous in some districts, and who either do not hold land at all,

or hold it only from year to year as sub-tenants. There are no

manufactures except a little knitting, and the 'Crofters' and 'Cottars'

constitute the great bulk of the population.

At one time, nearly all the land in the

western districts appears to have been held by 'Tacksmen' (generally

kinsmen or dependants of the proprietor) with sub-tenants under them.

But many of the lands formerly held by tacksmen, came afterwards to be

held directly of the proprietor by joint tenants, who grazed their stock

in common, and cultivated the arable land in alternate ridges or `rigs,'

hence called 'runrig.' Each person thus got a portion of the better, and

a portion of the worse land; but no one held two contiguous ridges, or

the same ridge for two successive years. Since the early part of the

present century however, the arable land has mostly been divided into

fixed portion -among the joint tenants, who thus became `Crofters,' the

grazing remaining in common as before. This division of the arable land

into separate crofts, no doubt led to improved cultivation; but it also

led to other consequences, to which it is necessary to advert.

Whilst the land was field by joint tenants,

no one could -appropriate to himself any particular share or portion,

his co-tenants having a concurrent right over the whole; but on the

division and absolute appropriation of the arable land, the crofters

generally established themselves each on his own separate allotment.

Their houses were and still are of the simplest construction, erected by

themselves of stone earth or clay, with a covering of turf and thatch.

The furniture consists of a bed, a table, a few stools, a chest, and

some cooking utensils. At one end of the house is the byre for the

cattle, at the other end the barn for the crop. The peat which the

crofter cuts from the neighbouring moss, gives him fuel. His capital

consists of his cattle, his sheep, and perhaps a horse or two; of his

crop that is to support him- till next harvest, and provide seed and

winter provender for his animals; of his furniture, his implements, the

wood-work and rafters of his house, and sometimes a boat or share of a

boat, nets and other fishing gear; with barrels of salt herrings, or

bundles of dried cod or ling for winter use. His croft supplies him with

food and most of his clothing. The sales of cattle pay his rent, and he

lives or rather did live in a rude kind of abundance, comparatively

idle, and knowing little of the daily toil by which labourers elsewhere

obtain a livelihood. Once established on his small farm, the crofter

does not expect to be removed so long as his rent is paid, and the

occupation of the croft becomes in fact hereditary, the son succeeding

the father as a matter of course.

The crofts appear to have been originally

apportioned with a view to the maintenance of a single family. "But when

kelp was largely and profitably manufactured, when potatoes were

extensively and successfully cultivated, when the fishings were good,

and the price of cattle high, the crofter found his croft more than

sufficient for his wants, and when a son or a daughter married, he

divided it with the young couple, who built themselves another house

upon it, Iived on the produce, and paid a part of the rent;" and thus

many crofts which still stand in the rent-roll in the name of one

tenant, became occupied by two three or four families, the population

continually increasing, and a large part of the increase having in this

way accumulated on the crofts.

The kelp manufacture, which at one time gave

employment in the western districts to great numbers of the inhabitants,

contributed to a like result. The process lasted for no more than six

weeks or two months, but it was necessary to provide the people employed

on it with the means of living throughout the year; and small crofts

were assigned to them for this purpose, on the produce of which, with

their other earnings, they were enabled to live and increase. But this

entailed another serious evil, for when the manufacture of kelp was put

an end to by the substitution of a cheaper commodity, the people engaged

in it were thrown out of employment; and as they differed in habits and

language, and had little intercourse with other parts of the country,

they were not disposed to go in search of employment elsewhere, and

clung to their wretched homesteads with a tenacity found only among the

very poor. It is true that emigration to some extent did take place, and

was promoted by the proprietors, who became justly alarmed at the excess

of population beyond the means of employment. But those who emigrated

were for the most part the better description of tenants and crofters,

whose lands were then in most cases let for sheep-farming, by which

higher rents were obtained adding at the same time to the disproportion

between population and employment, and by consequence tending to depress

the condition of the bulk of the people; and thus to render them less

capable of bearing up against extraordinary privation, whether arising

from failure of the crops, the. inclemency of the seasons, or any other

cause. The

foregoing explanations may be regarded as applying to the islands and

western districts generally, and are probably sufficient for enabling

the reader to form a pretty accurate notion of the state of things

existing there. There would of course be shades of difference between

different parts of these districts; but on the whole, the description

above given of the social condition of the people, as well generally as

with particular reference to the proceedings under the Poor Law, will

with little exception be found applicable to all. As however Sir John

McNeill in the course of his investigation examined the principal

islands, as well as portions of the , main land, and reported separately

on each, it may be well to give the substance of a few of these Reports

by way of further illustration.

The population of Skye and the adjacent

islands of Raasay Rona and others parochially connected with it,

according to the census of the present year (1851) is 22,532. The number

of families is 4,335 which gives about five and one-fifth to a family.

The annual value of real property returned to parliament in 1843 was

22,103l. 15s. 5d., thus giving an average of about 20s. per head

on the population. Besides the higher-rented `tachsmen' and 'tenants,'

there are about 1,900 'crofters' at rents not exceeding 10l, the

aggregate of whose rents amounts to about 8,000l., and the

average of each taken singly to 4l. 4s. 1d. The produce of a

croft of this description will not provide a family with food for more

than half the year, so that the crofter must provide for the remaining

half by other means. In addition to these 1,900 families of crofters,

there are 1,531 families of `cottars' making together 3,431 families, or

17,842 individuals, depending either wholly as in the latter case, or

during half the year as in the former, on employment other than the

cultivation of their holdings for the means of subsistence. With the

exception of a little knitting introduced by the committee for the

relief of destitution, there is no manufacture of any kind in Skye, and

the only employment is such as prevails in pastoral and agricultural

districts, with occasional fishing. The rents have nevertheless been

generally well paid, and without the necessity of distraining, as have

likewise the poor-rates. A large quantity of meal has been purchased by

the inhabitants annually, since the potato failure in 1846; and in the

year ending 10th October 1850, according to the returns of the excise,

the whisky duty paid by retailers amounted to 10,855l., which is

"considerably more than double the amount expended on relief by the

destitution fund during the same year, and more than double the

consumption of whisky returned for the same district in 1845, the year

before the distress commenced."

With these facts before us, it is, as Sir

John McNeill remarks, impossible to resist the inference that the

destitution fund could have done little towards supplying the deficiency

of local means; and even when to the relief derived from the fund, is

added the expenditure under the Drainage Act, together with the produce

of the crofts and whatever else could be earned in the district, the

amount would still be insufficient to account for the people being able

to pay rent and poor-rates, to purchase large quantities of meal, to

keep themselves well clothed and the men well shod, and likewise to pay

10,855l. for whisky and probably half as much for tobacco. The

fact is, the labourers of Skye, like the harvesters of Ireland, paid

their rents and provided what extra articles they wanted or wished for,

by the earnings which they occasionally obtained elsewhere. "From the

Pentland Firth to the Tweed, from the Lewis to the Isle of Man, the Skye

men sought the employment they could not find at home." Previous to

1846, the young men only went, but since then the older men have found

it necessary to go. Both old and young however, whether crofters or

cottars, return for the winter, and remain at home mostly in idleness,

consuming their earnings and the produce of their croft, "till the

return of summer and the failure of their supplies warn them that it is

time to set out again."

Those whose means are insufficient to

maintain them through the winter, are necessarily exposed to much

privation, and to these the relief from the destitution fund has been

chiefly afforded; but although this relief is said to have been "

administered with remarkable ability and caution," it is universally

considered to have had a prejudicial effect on the character and habits

of the people, by inducing them to misrepresent their circumstances with

a view to participating in the relief, and causing them -to relax their

exertions for their own maintenance. Indeed with reference to the whole

of these districts, but more particularly to Skye, where the working

classes depend more upon what may be called foreign employment than in

any other, it is said to be the general opinion, "that the effect of the

continued relief after the unforeseen calamity of the first year had

been provided for, was on the whole to diminish rather than to increase

the means of subsistence in succeeding years." That the population

became less frugal, is proved by the greatly increased consumption of

whisky. The

aggregate population of Hull with the smaller islands of Iona, Ulva,

Inchkenneth, and others parochially connected with it was, 8,294

according to the census of 1851. In 1821 the population amounted to

10,612, but it has since then been reduced by successive emigrations.

The annual value of real property returned to parliament in 1843 was

17,576l. 16s. 2d. The ownership of property is more than usually

divided in Mull, the three parishes of which it consists belonging to no

less than twenty-one proprietors, the majority of whom are non-resident,

and all with the exception of four or five have acquired their property

within the last forty years. On all the recently acquired properties the

population has decreased considerably, owing to improvements in

agriculture, the formation of large farms, and the conversion of the

land into pasturage. But on the old hereditary properties there is still

a numerous population of crofters and cottars, and there as well as in

the village of Tobermory much distress has prevailed. The chief produce

has always been cattle and sheep, but previous to 1846 large quantities

of potatoes and barley or bere were annually exported. In 1845 from the

port of Tobermory alone, 15,410 barrels of potatoes were exported, at an

average price of 4s. 6d. per barrel. There is no information of the

quantities sent from other parts of the island, "but it is probable that

the total export of potatoes in that year from the three parishes of

Mull exceeded 30,000 barrels, and brought to the producers at least

6,750l."—Since 1846 no potatoes or bere have been exported, but a

large quantity of meal, probably not less than 15,000 or 20,000 bolls of

140lbs. has been annually imported, which at 18s. per boll would amount

to between 14,0001. and 18,000l.; and if to this be added the

value of the former exports, which have ceased since the failure of the

potato crop, there will appear to be a loss arising out of that failure

of some 20,000l. or 25,000l. annually. Yet the consumption

of whisky has increased since 1845, the quantity of undiluted spirit

sold in that year according to the excise returns, having been 8,701

gallons, whilst in 1850 the quantity sold has been 10,212 gallons. The

expenditure on ardent spirits in 1848 was estimated by the minister of

Tobermory to have amounted to 6,100l.; and as the value of the

meal distributed by the destitution committee in that year was 3,202l.,

it follows "that there was expended on ardent spirits by the inhabitants

of Mull in 1848, a sum equal to double the amount of extraneous aid

furnished to relieve destitution in that year.

The united parish of Kilfinichin and

Kilvickeson in the south-western part of Mull, includes the islands of

Iona and Inchkenneth. In 1755 the population was 1,685. In 1841 the

population had increased to 4,113. Since which year, and in consequence

of the abandonment of the kelp trade, it had been decreased by

successive emigrations, partly voluntary and independent, partly with

the aid of the proprietors; and according to the census of the present

year (1851), the population of the united parish amounts only to 2,999,

or one-fourth less than it was in 1841. The number of crofters is now

160, and the number of cottars about 250; so that there are 410 families

or 2,132 individuals iii the parish depending on wages for the whole or

the greater part of their living, the only employment being

agricultural, with, occasional fishing for cod, ling, and lobsters.

These employments are ordinarily inadequate to affording subsistence for

the labouring population, and in the four years since 1846, the duke of

Argyle appears to have expended in gratuities and wages 1,790l.

11s. 4d. in addition to the revenue derivable from his property in this

parish—"Yet all classes concur in stating that the condition of the

people has progressively declined since 1846; and in 1850, after the

emigration, there were at one time of the inhabitants of this property,

not fewer than 1,000 individuals receiving relief from the destitution

fund."

'1'llc united parish of

Kilninian and Kilmore, cornprising the northern part of Mull, includes

the islands of Ulva and Gornetra as well as some smaller islands. The

land in this parish is divided among nine proprietors, most of whom have

acquired their property within the last twenty years. The population in

1755 was 2,590, and it went on increasing till 1831, when it was 4,830;

since which it has continued to decrease, and by the census of the

present year (1851), it is 3,952. On all the recently acquired

properties except the village of Tobermory, the population has

decreased. In Ulva it has been reduced from 500 to 150, the proprietor

having, as he states, "no alternative but either to surrender his

property to the crofters, or to remove them." Nearly the whole of their

rents were paid from the wages they earned in manufacturing kelp, and

when that failed they were neither able to pay rent, nor to maintain

themselves. In four years there had been expended in wages labour and

gratuities, with a view to giving employment, not only all the revenue

derived from the property, but 3671. in addition. In short, it is

declared that wherever the crofters have remained undisturbed, there

distress prevails, or is only averted by the interposition of the

proprietor, often at a cost exceeding the rental of the property. Many

of the labourers of Mull, like those of Skye, go to the south for

employment in summer, and the number that do so is said to be

increasing. The amount of imports, and the expenditure on whisky, while

the biome produce has so materially decreased, show that their gains

must be considerable. They all however, like the other islanders, return

home for the winter, their attachment to their native soil and

repugnance to mingling with strangers, keeping them from settling among

their southern neighbours, notwithstanding the frequent intercourse

which has of late years been maintained with them.

On the Gairloch property, situated on the

mainland nearly opposite to Skye, an attempt was made five years ago to

enable the crofters to maintain themselves, by introducing improved

anodes of cultivation. The Gairloch tenantry appear to have occupied the

grazing land in common, and to have cultivated the arable land in 'runrig,'

down to 1845 or 1846, when separate crofts were allotted to each. Their

number was then about six hundred, but as the land previously in

cultivation would not furnish each crofter with a sufficient quantity,

waste land was reclaimed for the purpose by the proprietor, the

principle proceeded upon being, that a croft of four or five acres

properly cultivated, with hill grazing for cattle and sheep, was

sufficient for the maintenance of a family and the payment of rent. The

land was successively trenched and drained, the crofters meanwhile

subsisting on the wages they received for performing the work. In about

four years the operation was completed, at an outlay of 6,000l.

in improving the crofts, and 7,000l. more in road-making draining

and trenching on other portions of the estate, making together 13,000l.

expended in payment for labour on this property in course of four years.

Of this amount 3,000l. was, we are told, furnished by the

destitution fund. The crofters were required to adhere to a four-shift

rotation of crops, the house-feeding of cattle, and the preservation of

liquid and other manures, and an intelligent overseer was appointed to

superintend and direct their proceedings. The result however has fallen

far short of what was expected, for although the Gairloch crofters have

undoubtedly benefited by the money expended among them in wages, and

their crofts yield a greater produce, and their mode of management is

generally improved, they are yet unable to maintain themselves by their

crofts for more than half the year, and for the other half are still

dependent on other sources. The improvements made in the crofting system

at Gairloch, at so large an outlay, have therefore failed in producing

results materially differing from those which have attended the system

wherever else it has prevailed.

The state of things exhibited in the

foregoing details, which apply generally to the whole of the western

districts and islands, is unknown in other parts of Scotland. There must

therefore be something peculiar in the circumstances which caused so

great an amount of distress in those districts on the failure of the

potato crop, while a similar failure was comparatively little felt in

other parts of the country. The potato no doubt constituted a larger

portion of the food of the, inhabitants of those districts than was the

case elsewhere, but this alone will not account for the continuance of

distress, after other crops might have been and actually were

substituted for it; neither will it account for the failure of the

efforts which were made to enable the crofters cottars and labouring

classes generally, to produce enough for their own maintenance—" efforts

(it is remarked) so great and persevering, and involving so large a

sacrifice of personal interest on the part of the proprietors, that they

reflect credit not only on those who made them, but even on the country

in which they were made." One of the reasons usually assigned for this

failure is the small size of the crofts, the land which was sufficient

to produce food for a family while the potato flourished, being

insufficient to supply corn enough for the purpose ; and this is

doubtless true, but it is not the whole truth. A man must have the means

of living whilst lie is cultivating his croft, and he must have

sufficient seed, implements, and cattle to make the land productive, so

as to enable him to pay rent. If he has not the menus of providing these

things, or the skill to apply them, he will not be able to obtain a

subsistence from his croft, and the larger it is the more of these

things will he require.

But independently of capital and skill,

which are always necessary to success whether the quantity of land

occupied be large or small, the quality or the soil and the nature of

the climate are also important considerations. Some land is so poor that

with the best management it will yield but a very scanty return, and

there are districts where the climate is so precarious and ungenial that

the ripening of corn crops is far from certain. Both these unfavourable

circumstances of soil and climate prevail to such an extent in the

western districts of Scotland, that oatmeal produced on the eastern

coast at the same or a higher latitude, can be supplied to the

inhabitants of the west at a fourth less cost than it can be produced at

there. The nature of the soil and the uncertainty of the climate are

therefore circumstances which materially add to the difficulties of the

crofter's position in the western districts, and these difficulties are

still further increased by the tendency to an excess of population which

the crofting system necessarily gives rise to. The distress existing

wherever that system prevails cannot be attributed to the failure of the

potato alone, since no such severe and continued distress has been

produced where there were no crofters; and it must therefore be regarded

as a consequence of the potato failure taking place, concurrently with

the prevalence of a system by which men are led to depend for

subsistence on the food produced by their own labour, on land occupied

by themselves. If

the occupancy of land were to be made the sole means of subsistence for

the population, as the crofting system implies, and if it were possible

to furnish every crofter with the necessary capital for this purpose,

the plan advocated by some persons of giving to each family land

sufficient to maintain them and pay rent, would still be found

impracticable. For instance, in the case of Skye, with its 3,431

families—To provide each of these with even as much land as is now Iet

in Skye for 10l., would require more land than both the islands

of Skye and Lewis could furnish, and would require every one paying a

rent above 10l. to be removed; so that even if the requisite

capital could be procured for establishing each family on its own croft,

the division of land into crofts of a size sufficient to supply the

families with food throughout the year, would necessitate the removal of

the larger part of the present population, including all those who

employ labour, or who possess the means of giving employment. This shows

the great disproportion existing between the population and the ordinary

means of subsistence, not only in Skye but in the western districts

generally, the inhabitants of which are said to "have neither capital

enough to cultivate the extent of land necessary to maintain them if it

could be provided, nor have they land enough were the capital supplied

them." Under these

circumstances, the only remedy seems to be emigration. The question is

not new, nor the emergency altogether unforeseen. Distress prevailed in

the same districts in 1837, and again in 1841, and on both those

occasions the necessity for emigration was strongly advocated, as a

means of averting the evils that were otherwise certain to ensue. The

recommendation was partially acted upon, but not to a sufficient extent,

as the present state of these districts abundantly proves.

In commenting on the circumstances of these

western districts, Sir John McNeill remarks—"It is curious, and perhaps

mortifying to observe, how little the difference of management and the

efforts of individuals appear to have influenced the progress of the

population, and how uniformly that progress corresponds to the amount of

intercourse with the more advanced parts of the country, and the length

of time during which it has been established." The proprietor no doubt

has it in his power to promote or retard advancement, "but the

circumstances (it is observed) that determine the progress of such a

people as the inhabitants of these districts, in the vicinity and

forming a part of a great nation far advanced in knowledge and in

wealth, appear to be chiefly those which determine the amount of

intercourse between them. Where the intercourse is easy and constant,

the process of assimilation proceeds rapidly, and the result is as

certain as that of opening the sluices in the ascending lock of a canal.

Where the intercourse is impeded or has not been -established, it may

perhaps be possible to institute a separate local civilization, an

isolated social progress; but an instance of its successful

accomplishment is not to be found in these districts."

This proposition is exemplified by a

reference to the Highland parishes on the borders of the Lowlands,

which, although still inhabited by the original race, are said to be

"hardly distinguishable by their aspect or the condition of their

inhabitants from those which bound them to the south or east. Proceeding

northward and westward, the change is gradual and uninterrupted, till

the utmost limits are reached in the outer Hebrides, where it is

complete." The extent and urgency of the distress, it is added, increase

in like manner with the distance from the centre of civilization and

industry, and are greatest where the intercourse is least. "The state of

the population is most advanced where the intercourse has been longest

established, and there too the distress is less severe, and the prospect

of extrication more hopeful." It follows therefore, that whatever tends

to facilitate and promote intercourse between these districts and the

more advanced parts of the country, ought to be encouraged, as being the

most certain if not the only way of bringing about a state of things

similar to that which exists in other parts, where less than a century

ago the people were as badly situated, but are now self-sustaining and

prosperous. Every attempt at improvement that is opposed to or

inconsistent with this progress of assimilation, will not only be

unsuccessful, but will, it is observed, tend eventually "to subject the

people involved in it to another process of painful transition." Of the

correctness of this opinion there can be no reasonable doubt, and it

behoves the proprietary and influential classes to keep it constantly in

view, in whatever efforts maybe made for ameliorating the condition of

these districts.

With respect to the administration of the Poor Law in the western

districts, it is said to be "on the whole creditable to the local

boards, when the difficulties they have had to contend with almost since

their foundation are taken into account." The composition of the boards

is said to be generally good, and the election of a certain number of

the members by the ratepayers has here as elsewhere given confi dcnce to

their proceedings, and increased their efficiency. The defects are such

as almost necessarily arise from the great extent of the parishes, the

difficulty of communication, and the limited choice of efficient

officers. The funds now raised, are far greater than were raised in

1845, and seem sufficient for meeting the ordinary calls for relief

under the statute. They appear moreover to be fairly assessed, and are

collected with less difficulty and fewer arrears than was to be

expected, considering the number of small ratepayers and the distress

that has prevailed. The parochial boards in the distressed districts,

are now, it is said, relieving all able-bodied persons who are in a

state of destitution, and Sir John McNeilf concludes his Report by

declaring, that "there is good reason to hope that this season (1851)

will pass away, not certainly without painful suffering, but without the

loss of any life in consequence of the cessation of eleemosynary aid."

If hereafter however, the population should be left entirely dependent

on their own resources, "some fearful calamity" will, it is added,

probably occur, unless a portion of the inhabitants remove to where the

means of subsistence are obtainable in greater abundance, and with

greater certainty, than where they now are.

The foregoing description of the distressed

districts of the west, chiefly abstracted from Sir John McNeill's

comprehensive Report, will it is hoped not be deemed irrelevant or

unimportant. The circumstances of these districts are in no , small

degree exceptional, and as the Poor Law applies to them in common with

the rest of Scotland, some account of their actual state appeared to be

necessary for judging of the operation and applicability of the law; and

from no other source could such an account be so appropriately drawn.

We will now turn to the Report of the board

of supervision, the seventh of the series being the next in order. It

appears that several of the parochial inspectors had either failed to

perform their duties, or been negligent and irregular in the execution

of them, and the board of supervision had found it incumbent upon them

to dismiss six, and to accept the resignation of others whose conduct it

would otherwise have been necessary to bring under investigation.

Several of the inspectors likewise were admonished on account of their

failing to observe the regulations, more especially that which prohibits

their deriving any profit or emolument directly or indirectly from

dealings with paupers. Indeed it would seem that the members of the

parochial boards were not themselves altogether faultless in this

respect, there being, it is said, reason to fear that in some cases the

prospect of a preference in executing work, or in furnishing supplies,

had served1 as an inducement for seeking a seat at the board. This is

obviously and perhaps unavoidably a weak point in the system of

parochial management, and it requires a vigilant watchfulness on the

part of the superintending authority. Experience showed that a frequent

examination into the proceedings of the parochial boards was necessary

for securing efficiency and preventing malversation, and a visiting

officer was accordingly appointed, whose duty it was to visit the

different parishes, and report upon the manner in which the law was

administered in each. For this purpose the country was divided into

districts, to be visited in succession, somewhat in the way that the

inspectors' districts are attended to in England.

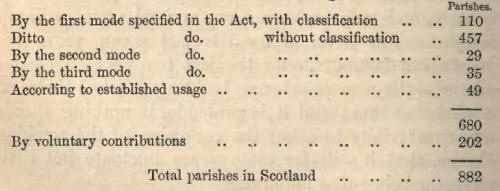

Since the last Report, 18 parishes which had

before raised the funds for relieving the poor by voluntary

contributions, resolved to raise them by assessment. The number of

parishes now assessed was 671, and the number still adhering to the

voluntary system was 211, the total number having been increased to 882

by the parishes of Stronsay and Eday in Orkney, previously conjoined,

being now declared separate parishes. The parishes assessed on "means

and substance" were 5 less than last year, although the number of

parishes assessed is we see considerably greater.

Four parishes in the Isle of Skye,

containing a population of 13,569, had combined for the purpose of

erecting a poorhouse, the plans of which have also been approved, as

have likewise the plans for improving and enlarging several others. The

number of permanent poorhouses in operation was 24. The number of

parishes that have poorhouses either singly or in combination with

others, was 44; and besides these, there were 119 parishes with a

population of 529,761 which take advantage of the existing accommodation

by boarding their paupers in the poorhouses of other parishes. The whole

of the population to which poorhouse accommodation is thus in some way

available, amounted to 1,283,805, or nearly half the entire population

of Scotland. In

reference to a communication from Lord Selkirk, describing the

successful operation of the Kirkcudbright poorhouse, and which is given

in the appendix to the present Report, the commissioners observe, that

"the result has been not only a considerable pecuniary saving to the

combined parishes, but a great diminution of labour to the persons

engaged in the management of the poor; and what is even more important,

a great diminution of the demoralizing effects produced on certain

classes by the temptations of out-door relief, in the absence of

sufficient means of checking abuse by applying an adequate test." The

opinion thus expressed by the commissioners, Will not cause surprise to

those who have attended to the progress of the Poor Law in England; but

that the conclusion should have been drawn from the experience acquired

in administering the law in Scotland, is peculiarly gratifying, and is

calculated to give increased confidence in the soundness of the

principle on which the English workhouse system is founded.

With respect to medical relief, it appears

that 599 parishes have complied with the conditions entitling them to

participate in the parliamentary grant, being 41 more than last year.