|

Prince Albert having

signified his intention of enjoying the sport of shooting, by having

a battle of the woods of Taymouth, on Thursday the 8th of September,

no one in or about the castle had ever before felt so deep an

anxiety for fine weather as they did that morning, and all were

disheartened when they beheld the sun rising among clouds. Lord

Breadalbane, who was naturally more anxious than any one, w^as early

astir, and roused his brother-in-law, Mr. Baillie of Jerviswoode, to

aid him in making the necessary preparations. Meeting the Prince’s

secretary, Mr. Anson, in front of the house, he said to him, in

allusion to the doubtful appearance of the sky, “The Prince don’t

mind a little rain,—eh, Anson?”—“Oh, no,” replied Mr. Anson, “He

won’t mind a shower.” Accordingly, soon after nine o’clock, ponies

were brought to the door, and His Royal Highness, who had

breakfasted with Her Majesty at eight o’clock, appeared in a black

velvet shooting-jacket, shepherd’s tartan trowsers, a low-crowneil

grey hat, and cloth gaiter-boots, and having mounted, he rode off,

attended by the Marquess and Mr. Anson. Taking the way to the

eastern gate, they went about two miles along the Aberfeldy road,

that they might begin by beating Tullochuille woods, and so come on

westward through the covers of the southern hills. About thirty or

forty foresters only were required at first. They were all fine

athletic men, in Highland dresses of shepherd’s tartan, and each

with his powder-horn slung over his shoulder. They were under the

command of Mr. Bowie Campbell of Clochfoldach. Mr. Baillie of

Jerviswoode joined his noble brother-in-law in the woods, as did Sir

Alexander Campbell of Barcaldine.

The Prince having dismounted, climbed the hill, and, attended by his

own juger, and Mr. Guthrie, head keeper to Lord Breadalbane, he took

his post on a steep slope within the narrow part of an extensive

plantation, whilst the foresters went on for a mile or two

eastwards, in order to beat westwards in his direction. He had three

double-barrelled rifles and fowling-pieces, which were loaded by his

juger, and successively handed to him as he required them, by Mr.

Guthrie, who stood immediately behind him. It was raining; but, as

Mr. Anson had predicted, the Prince made no account of the wet,

being keenly bent upon his sport, which soon became extremely

animating, the distant shouting of the beaters becoming every moment

louder and nearer, till the roe-deer began to come bursting along,

and, with three successive shots, His Royal Highness killed three

very fine ones. The next station was on the western side of a

ravine, in the extensive Croftmoraig hill plantation, through which

runs a little brook, and there, though the wood was much younger,

and consequently denser, the Prince, with great expertness of aim,

shot different kinds of winged and ground game; and an owl, which

was disturbed, having come in his way, was likewise speedily

numbered with the dead. The Prince had then a considerable extent of

old fir wood to traverse, where he had some long shots at black

game, particularly at a black-cock and a grey hen, both of which

were killed at great distances. This is a favourite haunt of the

capercailzie, two of which noble birds fell before the Prince’s gun.

The shooting scene was most interesting to the few who witnessed it,

but it also produced a fine effect to those in the valley below,

whither the shrill shouts of the people, and the smart reports from

the Prince’s rifle, came echoing from afar, whilst the smoke created

by each shot rose out of the wood, and hung lightly over the trees

in the damp air, mellowing the hues of the foliage. The beauty of

all this was increased as the party came westward to the Braes of

Taymouth, opposite to the castle, where His Royal Highness took up

his third position, and had some good sport. But keenly as the

Prince seemed to enjoy the pastime in which he was engaged, he

allowed none of the magnificent prospects, that were every now and

then bursting upon him through openings among the woods, to escape

his notice, and he was continually expressing his admiration of them

to his noble host. Climbing over the high moorland, and beating

around the outside of the larch woods, the Prince killed three brace

of grouse. Some time previous to this, Lord Breadalbane having

thought that there were too few men out, called a Highlander, and

said to him, “Run to the castle, and order fifty or a hundred men

more to come up directly,” a princely command that was obeyed with

all manner of alacrity; and now that the whole body spread

themselves out in line over the heather, they seemed like men

rushing into action. The Prince, getting nimbly over a high wall,

placed himself in a position, whither the beaters, inclosing a large

circle of the wood, and gradually contracting it as they advanced in

his direction, drove so many roe-deer towards him, that he killed

nine without leaving the spot. On his way clown through the open

ground, His Royal Highness observed a fine old black-cock, at about

two hundred yards off, below a little knoll, and showed great skill

as a sportsman by stalking him. Keeping the knoll between him and

the bird, who sat on a hillock with his eye jealously watching the

people above, the Prince crouched down, so as to conceal himself,

and stealing slowly forward, until he got as near to the bird as he

could, he picked him off with his rifle at a long shot.

Whilst descending the Braes of Taymouth, a prospect of remarkable

grandeur burst upon the Prince’s eyes, and he several times

exclaimed to Lord Breadalbane, “That is really beautiful!” The noble

castle was seen from this elevated position forming the central

object in the lovely valley below, with the Royal banner floating

from its battlements. Immediately behind it towered up the

forest-covered face of the hill of Drummond. The numerous figures

moving about the castle, and among the various glades running

everywhere through the mazes of its woodland, gave animation to the

scene—whilst the Tay was seen meandering through the green and

tufted lawns, in its course from the broad sheet of its lake, that

stretched away far westward, until lost amid the distant mountains,

among which Benlawers and Benmore were most conspicuous. At the

nether extremity of the lake, and close to the origin of the river,

was the Ceaunmore, or Big-head—the peninsula, from the venerable

groves of which the pretty church of Kenmore was seen peeping

modestly forth— and the beautiful wooded island in the lake a little

way above, with the ruins of its ancient priory, founded in 1122 by

Alexander I., where his Queen Sybilla died, and where her remains

are deposited.

The Prince proved himself to he a practised shot and a most active

pedestrian. His last stand of this day was in the Tower Park, a

little below the high tower inhabited by the head-keeper.

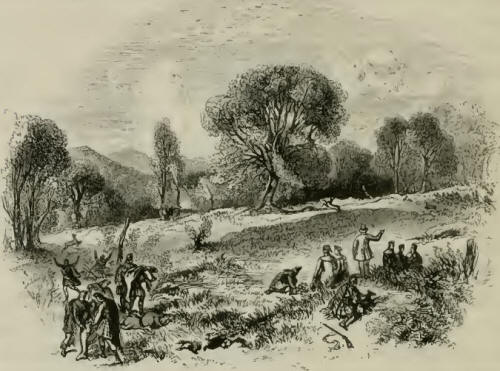

This is a picturesque spot, and the whole scene of the shooting here

was finer than any of the others. A narrow road runs diagonally up

the hanging side of the hill, where there is a circular opening in

the wood, broken by irregular groups of trees. Near one of these

stood the Prince, commanding the pass, with his two attendants;

whilst Lord Breadalbane and the other gentlemen placed themselves on

the skirt of the wood at some distance in his rear, with those who

carried the dead game. The beaters who were driving the wood from

the eastward, forced so many roe-deer on before them at this place,

and closed in so rapidly themselves, that men and roe-bucks became

mixed up together in confusion. The Prince had repeatedly, during

the day, manifested the most perfect coolness and self-command,

having frequently raised his gun to the object, and taken it down

again, because he had reason to suspect that there might be a man in

that direction. His Royal Highness’s care in this particular

delighted the Highlanders. At this last stand five roebucks appeared

together at one moment, and the Marquess called out, “Shoot,

sir!—fire, sir!” to which the Prince replied, without raising his

gun, “No, I will not; for, if I do, I may shoot a man.” And

immediately afterwards, when the animals came out in great numbers,

he let them all escape, except such few individuals as he felt

assured he might shoot without doing injury to any one. Imagine this

glorious scene, a pretty piece of woodland in itself, with the

Prince and his two attendants near a picturesque ash-tree, group

with thorns and other smaller growths; the Marquess, and the

gentlemen that were with him, and the foresters with the game,

forming a fine set of foreground figures. The roebucks, and ground

game of all kinds, bursting from every part of the inclosing woods

and brakes around—and the beaters, obscurely seen within the shadows

of the deeper forest, or, singly catching the light as they advance

into the looser parts of it—whilst the winged game were ever and

anon skimming in wild alarm across the field of sky above—the wild

halloos—the whistles—the clapping of hands—the occasional smart

crack of the rifle—and you have a picture of the most striking and

interesting description.

As the Prince in his homeward way crossed the public road that runs

along the hill, he was recognised by a number of ladies and

gentlemen, who were overjoyed at this favourable opportunity of

beholding him, and he courteously acknowledged the marks of respect

which they paid him. Entering by a door of the park wall leading in

by the battery, the Prince came suddenly on one of the most perfect

of the elevated views anywhere to be enjoyed about Taymouth; for

whilst more extensive prospects are to be obtained from higher

points, and, on the other hand, those of a more pictorial

description may be had by going lower, yet there are few places

about the grounds where the happy medium between the two extremes is

so well preserved. The whole valley—its grand castle—its river— and

its bounding hills—with the bridge, and far-withdrawing lake and

distant mountains, are all seen without looking too much as from the

heavens upon them. His Royal Highness expressed very great delight

in the contemplation of this truly grand scene, and taking a short

cut with Lord Breadalbane across the park, he got to the castle a

little before two o’clock.

The Prince was out altogether about six hours, and the distance he

walked may have been about six or eight miles. Under more favourable

circumstances of weather, a much greater quantity of game might have

been shown him. It was very amusing to hear some of the Cocknies,

who had come the hundred miles to witness these stirring scenes,

call this day’s work deer-stulking, and magnify the fatigues and

perils which the Prince had undergone, till the recital outdid

anything that might have arisen out of real deer-stalking itself, or

that has been recorded in Mr. Serope’s graphic descriptions of that

royal sport. Had the time devoted to this Royal tour admitted of the

Prince visiting the forest of the Black Mount, belonging to the

Marquess, about fifty miles from Taymouth, he might then have

partaken of deer-stalking in right good reality. That part of the

Black Mount, or Corrichibah forest, which is strictly preserved for

deer, contains above 35,000 acres. From the ancient family

manuscript in the Taymouth library, called the Black Book, and from

some other documents, it appears that this extensive district of

wild mountain was preserved as a deer forest from very early times.

If any of the Londoners, who witnessed the battue in the woods of

the Braes of Taymouth, were to try deer-stalking in the forest of

the Black Mount, they would soon be made aware of the difference

between the two kinds of sport, stalking being extremely arduous

there from the very steep and rugged nature of the ground. Some

years ago a poacher, who was pursuing the deer there, lost his

footing, and was killed by falling over a rock.

Her Majesty, availing herself of an

improvement in the weather towards mid-day, set out to walk,

accompanied by the Duchess of Norfolk, and attended by a single

footman in the Royal livery. Although Lord Breadalbane had thrown

the grounds quite open to the public on the previous day, the

strictest orders were now given to exclude every one, that the Queen

might, if it so pleased Her Majesty, enjoy them in perfect privacy.

So literal were the Highland gatekeepers in giving obedience to this

command, that even after they had seen some of the gentlemen who

were living at the castle pass out, they could scarcely be brought

to reamit them, “as they had orders to let no one in who had not a

card of a particular kind,” and a near connexion of Lord Breadalbane

required to exert considerable authority, before he could induce a

gatekeeper to admit one of Her Majesty’s principal Secretaries of

State, and a lord of the bed-chamber. The Queen walked up the

river’s bank, until she came to the slopes of shaven turf, leading

up to the Dairy, which stands on the flattened summit of a very

beautiful little hill, clothed with trees and shrubbery of the

richest luxuriance of growth. It is a lovely spot, and the building

is worthy of the scene in which it is placed. It bears some

resemblance in plan to the dairy cottages of the Swiss chalets, and

is built entirely of dazzling white quartz rock. The western front

commands one of the most beautiful views to be found anywhere in the

grounds, and it is still more perfect when contemplated from the

rustic balcony of the upper story of the building.

The Queen walked in by the first opening that offered itself, which

happened to he the kitchen door. The damsels of the Dairy were

astonished to see so fine a lady, though they could hardly have

guessed that it was the fair Sovereign of these mighty kingdoms.

They showed Her Majesty the rooms, however, which are paved with

tesselated marbles, and of a delightfully cool temperature. The milk

was all laid out in nice brown Rockingham ware, and some of it in

clean wooden milk dishes, which are much preferred by the

dairy-maid. Many of the vessels are of fine raised china. These were

all placed on a shelf running round the apartment. Her Majesty

examined every thing, and made many enquiries, and expressed great

pleasure and gratification with all she saw. With her own hand, she

also essayed the operation of making butter, by turning the wooden

handle of a beautiful little china churn, worked by very nice wooden

machinery. The Queen asked for some oaten cake, but the dairymaids

had nothing of the sort. They, however, produced some cakes of a

more delicate description, which had been sent up to them as a bonne

louche from the castle, and they filled a glass with new milk for

Her Majesty, of which she partook with great good humour and

satisfaction. The Queen carried away with her the simple hearts of

the two dairymaids, who afterwards declared that she was as “humble

a laddy as they had ever seen.”

Upon quitting the dairy, the Queen walked through a bosky part of

the approach, where the pheasants were seen strutting across the

open green turf sloping down from the south side of the dairy,

between thickets of shrubs, the metallic lustre of their plumage

shining in the sun, whilst the active squirrels were frisking nimbly

about, rushing up the stems of the trees on the smallest alarm, or

springing actively from bough to bough, and peeping cunningly at

Majesty from some snug sylvan citadel where they were themselves

unseen.

The Queen pursued her walk along the western approach towards the

gate opening into the square of the village of Kenmore. Mr. David

Duff, the good parish clergyman, chanced to be walking in the

grounds with two friends. Seeing two ladies coming slowly towards

them, with a servant in the royal livery at some distance behind,

they at once suspected that it was the Sovereign, and were speedily

convinced, by the man waving his hand, to give them warning of the

Royal personage who was approaching. Standing aside off the road,

they respectfully uncovered, and the Queen most graciously

acknowledged their homage. Her Majesty at this time was some twenty

yards in advance of the Duchess. The road was wet and miry, in

consequence of the rain that had fallen, but Her Majesty seemed to

be little incommoded by this circumstance. Some time after she had

passed, the servant came back to enquire if there was any path by

which Her Majesty could return by the river-side. Such a path does

exist, the access to it being over an aha! fence by a sort of

drawbridge, but as the gentlemen had not remarked in passing,

whether it was up or down, they felt somewhat nonplussed, and in

their confusion they replied, that they did not know. The Queen took

a peep of the village through the iron grille, and then retraced her

steps by the same way to the castle, having been out nearly two

hours.

After Prince Albert’s return from shooting, the Highlanders were

seen approaching the castle, bearing the slaughtered game. First

came twenty roebucks, each carried between two foresters; next

followed men carrying two capercailzies, nine black game, and six

grouse; and the procession was closed by others with twelve hares,

one partridge, one wood pigeon, several rabbits, and the unhappy

bird of night. These were all exhibited near the foot of the iron

stair leading from the Queen’s gallery, and never was there a finer

subject for a picture than the whole of this scene, with the manly

forms of the Highlanders en groupe, and the dead game on the ground.

The Queen came down stairs to look at it, and a black-cock was

afterwards sent for by Her Majesty, that she might have a closer

inspection of it. The feathers of this bird were afterwards plucked

by the officers of the Highland Guard, and worn as trophies in their

bonnets.

About five o’clock in the afternoon, the

weather being still fair, the Queen’s carriages drew up at the door

of the castle, and soon afterwards Her Majesty came down with the

Prince, and they set out for a drive through the grounds. The

Duchess of Norfolk, and Lady Breadalbane, sat in the same carriage

with the Queen and the Prince, and Lord Breadalbane rode in advance,

for the purpose of directing the route. The Queen’s carriage was

preceded by two outriders, and followed by General Wemyss and

Colonel Bouverie as equerries. The second carriage contained the

Duchess of Buccleuch, the Marchioness of Abercorn, the Hon. Miss

Paget, and the Earl of Morton; and the Duchesses of Roxburghe and

Sutherland, the Countess of Kinnoull, and Lady Elizabeth Gower, were

in a third. Lord Breadalbane led the Queen's carriage along the

avenue to the Kenmore Gate, where Her Majesty found all the roads

outside of the park walls covered with multitudes of people, whose

cheers were so loud, that they were heard at the castle, a distance

of two miles. Turning down towards the bridge, the carriage stopped

under the triumphal arch for a few moments, to allow Her Majesty to

enjoy the magnificent view of the lake on the left hand, stretching

away amid its hills for miles towards the west, with its wooded

island and ruin, and the gay flotilla of boats and yachts—and to the

right, the Tay hurrying in one broad unbroken stream, as if eager to

enjoy his meandering course through those delightful grounds. Whilst

the Queen was contemplating these lovely scenes, a Royal salute was

fired from the flotilla, which greatly heightened the effect to the

eye, and gratified the ear by awakening the grand music of the

mountains. The spectacle was extremely animating. From the bridge

the Marquess led the Queen’s carriage by the garden, and by a new

drive he had recently ordered to be made expressly for Her Majesty,

for about a mile up the margin of the lake, whence they enjoyed

occasional peeps of its surface, where the roebucks are often seen

sipping the pure waters of the shallows, as they ripple gently

towards the shore. The carriages turned up into the Killin public

road, by which they came back to the gate leading into the park on

the northern side of the river. Here the Queen entered the beautiful

broad shaven-turf-terrace, following the course and windings of the

Tay, on its right, whilst the open park stretches along on the left.

At first the terrace is little raised above the surface of the

river, but it afterwards gently ascends to a point where stands a

beautiful faesimile of a fine old English cross, whence a rich and

varied view is enjoyed, looking up the bed of the river towards the

bridge and the village, with all their lovely accompanying features,

serving to throw back the retiring perspective of the blue lake with

its wooded hills and misty mountains. The terrace is now raised a

considerable height above the Tay. the steep bank being covered with

very noble timber, and the drive bordered by bending lines of trees,

throwing a complete shade over it. It preserves this character for

about two miles, affording occasional peeps into the wider grounds

on the south side of the river, where the castle stands, and

sweeping round to the point fortified by the Crown battery, whence a

view opens downwards into the little grassy holm of Inchadnie on the

south side of the stream, occupied by the camp of the Highland

Guard. Some little way beyond this, the Queen recrossed the river

over the noble wooden bridge of Inchadnie, whence Her Majesty

returned through a picturesque portion of the deer park, and by the

bridge over the burn of Taymouth, enjoying during this latter part

of her drive some extremely grand and pictorial views of the castle.

This charming drive, of about an hour and a half, very much

gratified the Queen. After Her Majesty was handed from her carriage

by her noble host, she remained for some time talking with him at

the entrance, admiring the fine stags’ heads, with which it is so

properly ornamented, and inquiring about their history.

Besides the Queen and Prince Albert, and the Marquess and

Marchioness of Breadalbane, the Royal dinner-party this day

consisted of the following- individuals :—

The Duchess of Norfolk,

The Hon. Miss Paget,

The Duke and Duchess of Buccleuch,

Lord and Lady Belhaven,

The Duke and Duchess of Roxburghe,

Sir John and Lady Elizabeth Pringle,

The Duchess of Sutherland,

Sir Neil and the Hon. Lady Menzies,

Lady Elizabeth Gower,

Sir George Murray,

The Marquess and Marchioness of Abercorn,

General Wemyss,

The Marquess of Lorne,

Colonel Bouverie,

Mr. Baillie of Jerviswoode,

Mr. Charles Baillie.

Mr. George Edward Anson,

Sir James Clark.

The Earl of Aberdeen,

The Earl of Morton.

The Earl of Mansfield,

The Earl of Liverpool

The entertainment, to which the Queen sat down towards eight

o’clock, was on the same scale of magnificence as on the previous

day. Her Majesty was in excellent spirits, and conversed freely with

those around her, and with much liveliness and intelligence.

John Mackenzie, the Breadalbane piper, played on the balcony outside

the windows during dinner. The healths of the Queen and Prince

Albert were given as usual, after dinner, and the band played. As

the Queen dislikes sitting long at table, she left the dining-room

early, and the gentlemen arose about ten minutes after Her Majesty,

so that all were in the drawing-room by a little after nine o’clock.

The etiquette of the Court was kept up, and Sir Neil Menzies, Bart,

of Castle-Menzies, and the Hon. Lady Menzies, were presented to the

Queen during the evening, when Her Majesty was pleased to pay some

compliments as to the beauty of their ancient residence, which she

had very much admired. The officers of the 6th Carabineers, and of

the 92d Highlanders, were also presented. In the course of the

evening Mr. Wilson, the vocalist, who had been expressly engaged by

Lord Breadalbane for this occasion, sang in the great hall. By the

Queen’s command, he had previously given in a list of some of those

Scottish songs for which he is so much celebrated, from which Her

Majesty selected “Lochaber no more,” “The Lass o’ Cowrie,” “Pibroch

of Donuil Dhu,” “Auld Robin Gray,” “Will ye gang to the Highlands,

Leezie Lindsay?” and “The Flowers o’ the Forest.” Mr. Wilson sang

all these with his usual powerful effect. No Jacobite song had been

given in the list, but after “The Lass o’ Gowrie,” Her Majesty

commanded “Wae’s me for Prince Charlie,” and “Cam ye by Athol?”

Besides these, Mr. Wilson was commanded to sing “John Anderson, my

Joe,” and “The Laird o’ Cockpen.” The Queen was pleased to express

herself highly gratified with Mr. Wilson’s exertions. Her Majesty

and the Prince retired about eleven o’clock to their private

apartments, and after a little pianoforte music and singing, the

rest of the company dispersed for the night. |