|

I was born in the parish of

Craignish, in the shire of Argyle, North Britain. My predecessors for some

years back were gardeners to a very ancient family of the name of Campbell,

whose seat gave name to the parish, viz., the Castle of Craignish. My father

had ten children of whom I was the youngest.

When I was about seven years of age my eldest brother married, and he being

bred a gardener, my father willingly dispensed with his place to see him

well settled, and took a small farm where he cultivated a garden, by which

and by the farm he lived pretty comfortably. He lived only four years on

this spot of ground when, being very well recommended, he was taken into the

Duke of Argyle’s garden, where he continued for the most part of the

remainder of his life. My father was never very rich, but had an excellent

spirit, and abhorred anything that was mean; he gave all his surviving

children as much education as was necessary to qualify them for business. At

the age of fourteen years I was hired by a man of the name of Livingstone in

the island of Scarba to teach his children to read and write. In this island

I stayed a year, and then I agreed with a set of honest farmers in a farm

called Killian, three miles west of Inveraray, the capital of Argyle. But

that farm, whereon sixteen families lived very comfortable, was taken by one

Captain Campbell, who kept a great many cattle, so the people were

dispersed, and my school broke up the May following. I then was hired to

teach a more extensive school in the adjoining parish, in a place called

Lochowside, where I continued to teach with great success for three years,

during which time I had the curiosity to learn to play on the bagpipes, an

instrument very much used in that part of the country. I was then

recommended by the minister of that parish and several others to a charity

school in the parish of Strathlachlan, where I continued to teach four

years; the managers of the charity school then thought proper to remove the

school to Strachur, the adjoining parish, and there I remained for two years

more, which I may safely say was the most agreeable part of my life, being

placed among a set of free and hearty gentlemen, who took a great deal of

notice of me and encouraged me very much.

But in the midst of my felicity I received a letter from Mr Lewis Macgregor,

inspector of the charity schools, with an order to remove from Strachur to

the parish of Tongue in the north part of the shire of Sutherland, and there

to teach a school newly erected by the Honourable Society for Propagating

Christian Knowledge. I must own I did not much like this news, being very

well contented with my situation where I was, and wanted no changing. I was

obliged, however, to comply with the order or lose my bread. Accordingly I

went to Greenock and agreed with the master of one of the herring fishing

vessels to take my chest on board and carry it to Badcall, an arm of the sea

in the north of Sutherland near the place where I was to set up school, I

myself choosing to travel it. So having parted with my good friends, the

gentlemen of Strachur, I went to my father’s house at Inveraray where I

stayed two nights, and in May 1776 set out for my journey.

The weather being excessively hot, I was obliged to make short stages. I

halted at Fort William, Fort Augustus, and at Inverness, and arrived at

Tongue about the middle of June, after I had travelled upwards of two

hundred miles. Being arrived at the minister’s house at Tongue, I was

informed that my school was to be erected at the distance of five miles

north-east from Tongue. I rested there that night, and early next morning

proceeded for Skerray (which was my destination), where I was very genteelly

received by Mr and Mrs Mackay of Skerray, and their daughter Anne who was a

widow, having been but a short time married to Mr Mackay of Melness, and

lived in her father’s house since his death. This lady, I may venture to

say, was as well accomplished as any that ever I was acquainted with, and

might have been married to very good advantage if she would, as she had

several good offers, but she chose to live single. The kindness and civility

I met with in this family is beyond my expression; in short, I was offered

to live in the family, and you may think that a stranger, as I then was,

would be glad of the offer.

This gentleman had two promising boys (who were his grandchildren) in his

house, who were both fatherless and motherless; and upon their account I was

extremely well used, the old people being fond of them even to a fault,

especially the grandmother. These two boys I had under my tuition both at

school and at home, and being extraordinarily well liked in the family I was

introduced into the best company in the country. This part of

Sutherlandshire is inhabited by the Mackays, a clan remarkable for their

loyalty, and for their hospitality to strangers, which I experienced very

much. I remained in Skerray’s family for two years, during which time I

lived very happy and might live so all my life only for my rambling

inclination.

About that time (1778) His Grace the Duke of Gordon got a commission to

raise a Highland regiment which was to be called the North Fencibles, and Mr

Mackay of Bighouse having a captain’s commission in that regiment I was

determined to go with him let the consequence be what it would, and that

contrary to the advice of all the gentlemen of the country, and particularly

the captain, who expostulated with me as much as he could to deter me from

enlisting, but all availed nothing. So on the 4th of June 1778 I enlisted

with Captain Mackay as pipe-major of the regiment and to have a shilling per

day. We stayed in the country recruiting till September, and then our party,

consisting of 1 captain, 2 lieutenants, 1 ensign, 5 sergeants, and 103

privates, marched from their different rendezvous to the Meikle Ferry, and

that night got billets in the town of Tain where we were very kindly

received. The next day we proceeded to Campbelltown, near Fort George, and

from thence to Elgin in Morayshire, which was our headquarters. That very

evening we arrived in Elgin I was despatched to the Duke of Gordon’s house,

where I was detained for ten weeks to play the pipes.

In November following the regiment was ordered to the garrison of Fort

George to be disciplined, and I was ordered to join my company at Elgin, but

before I left the duke’s house I received two guineas as a present from His

Grace for my music. We marched to Fort George in three divisions, and being

all arrived took up our quarters there for that winter. Everything was

reasonable in Fort George that year, so that we might have made a very

comfortable living of it if our men had been acquainted with a soldier’s

manner of living, but, what through indolence and excess of drinking, a

great many of them fell sick and some died.

At that time Colonel George Mackenzie, son to the late Earl of Cromarty, was

raising a second battalion for the 73rd regiment of Highlanders, and had his

headquarters at Inverness. He used to come frequently to dine with the

officers of the North Fencibles, where he had an opportunity of hearing me

play the pipes, which so pleased him that he earnestly wished to have me in

his regiment, and applied himself closely to Captain Mackay for my

discharge; but he, judging I would not agree to go abroad, never acquainted

me with the colonel’s design till the colonel himself attacked me in person,

after the 73rd had been embarked at Fort George. As he offered me very good

terms I consented to go, and accordingly I was sent to Gordon Castle post

haste for my discharge, with letters from the colonel and Captain Mackay for

the duke. I arrived at Gordon Castle that night, and next morning had my

discharge signed by the duke, but before I returned to Fort George the

transports with the 73rd on board had sailed. However I had received

directions how to proceed in that case from Colonel Mackenzie, which was to

take passage in the first vessel to London, and proceed from thence to

Portsmouth where I should meet the regiment, as they were to wait there some

time for orders from the War Office.

Agreeably to the colonel’s directions, after coming to Fort George I got

cleared off from the North Fencibles and went to Inverness to buy some

necessary articles, and upon enquiry found that there was a vessel there

taking in goods and passengers for London. So I agreed with her captain for

a cabin passage (for which I paid a guinea and a half, and was found in

victuals and drinks), put my things on board, and went by land to Cromarty,

where the vessel was to call for passengers, which she did. On the 2nd day

of April 1779, I embarked at Cromarty, and the same evening we set sail for

London with a favourable breeze, which increasing soon cleared us of the

firth.

We sailed close along shore after we cleared Peterhead, for fear of French

and American privateers that infested the coast at these times. Our passage

was extremely agreeable, meeting with a great many ships and small craft

that traded along the coast. We likewise met several fishing boats who

supplied us with fresh fish at a very cheap rate. Off Sunderland we joined a

large fleet of colliers bound for different parts of England, and kept

company with them till we came to Yarmouth Roads, they keeping to sea

farther than we wanted. After coming through Yarmouth Roads we anchored in a

small bay waiting for the tide to carry us to the Nore, to which we

proceeded next morning and had a very pleasant prospect of the country on

both sides of the Thames, arriving at Hawley’s Wharf that afternoon after a

pleasant passage of seven days from Cromarty to London.

Being now arrived at the grand metropolis, I was rather at a stand how to

proceed, being an entire stranger. I had no sooner set my foot on shore,

however, than I met two particular school-fellows of mine, then soldiers in

the third regiment of Foot Guards, who being very well acquainted in London

soon found very good quarters for me; and after having drank very heartily

together we parted for that night, having first set a time and place to meet

next day. The day following I waited upon Messrs Bishop and Brummel, agents

to the 73 rd regiment, with letters from Captain Mackay, and an order from

Colonel Mackenzie for whatever money I might have occasion for to bring me

to the regiment. Here I was informed the 73rd was then on board the

transports at Spithead waiting for an order to land, and that I had no

occasion to be in any hurry. The next day I and my old school-fellows met at

Wapping and passed the day very merrily together. I then went to have a view

of Westminster Abbey and several other curiosities in London. And after

having spent a week in London I thought it high time for me to set out for

Portsmouth.

On the 16th April 1779, I left London, and on the 18th I arrived at

Portsmouth, to find Colonel Mackenzie and the most part of the officers of

the 73rd at the Fountain Inn. The colonel expressed a great deal of joy at

my arrival, and showed me all the marks of kindness I could naturally expect

of one of his rank; nor did his goodness stop here but continued always

fresh during my stay in the regiment. Two or three days after my coming to

Portsmouth I settled with the colonel about my bounty and subsistence, and

he very cheerfully laid down twenty guineas of bounty money, and the arrears

of my pay since I left Fort George at one shilling and sixpence per day.

On the 7th May the route came from the War Office for the regiment to land,

which they did the next morning at Portsmouth Common, and the same day

marched to their different cantonments as directed by the route. The

colonel’s, major’s, and Captain Macintosh’s companies, together with the

grenadiers and the light infantry, marched as far as Petersfield in

Hampshire, where they rested for two nights, and on the morning of the 10th

of May the grenadiers and light infantry set out from Petersfield to Alton

and Farnham in Surrey. The whole regiment was dispersed in the different

cantonments allotted, and now, being a little more settled, the colonel

appointed me to his own company and to be pipe-major for the regiment, there

being two more for the grenadier company, and one for the light infantry.

We stayed in these cantonments till the 24th of June, when the two flank

companies joined us at Petersfield, and marched along with us to Hilsea

Barracks where we were joined by the other five companies, and marching all

in a body to Southsea Castle, we embarked on board the transports waiting to

receive us. On the 25th June 1779 we sailed from Spit-head under convoy of

two frigates, with some drafts for different regiments aboard, and two days

after we arrived in Plymouth Sound. On the 27th we landed at Mutton Cove,

and marched directly into Plymouth Dock Barracks, where we remained until

the 24th July, when we received an order to remove from Dock Barracks and

encamp a little beyond Maker Church, on Lord Edgecomb’s estate in Cornwall.

The troops which composed this camp were the 1st battalion of the Royal

Scots on the right, the Leicester and North Hampshire militia regiments in

the centre, and the 2nd battalion of the 73rd regiment on the left.

During our stay in this camp, the French fleet, which was so much dreaded,

appeared off the Ramhead; some of them sailed close by the Sound and had a

fair view of the garrison of Plymouth, the shipping, &c. The formidable

appearance of this fleet, and the nearness of their approach, struck such

terror in the breasts of the inhabitants of that coast, that the most part

of them left their houses and fled to the interior of the country, taking

their cash and most valuable effects with them. They returned, however, in a

few days after the French fleet disappeared. Soon after this the merchants

and gentlemen of Plymouth, and all the little towns adjacent, raised

companies of volunteers for the defence of their country and properties, and

the place all round was fortified with batteries and guns for the better

reception of the French, should they make an invasion on these coasts.

We remained encamped on this ground till the 24th November, then broke up

camp and marched back to our former barracks at Plymouth Dock, and soon

after were informed that we should be among the first troops for foreign

service, but our destination5 was not known. Accordingly, on the 8th

December 1779, we marched from Dock Barracks, and that same day embarked on

board the transports that lay then in Catwater waiting for such troops as

were going aboard. It was my chance to go on board the “Dispatch” transport,

Captain Munro, who behaved very well to the men in general.

We were detained there at anchor waiting for a convoy till the 27th

December, and then sailed from Plymouth Sound under convoy of six sail of

the line and two frigates, and joined the grand fleet under the command of

Admiral Sir George Bridges Rodney off the Ram-head that same evening. The

fleet was really a very pretty sight, consisting of about twenty-four sail

of the line, nine frigates, with a considerable number of armed ships, store

ships, and a great many merchantmen, to the amount of one hundred and fifty.

We continued our voyage with a pleasant gale till the 8th of January 1780.

About four o’clock in the morning we discovered a large fleet bearing down

upon us mistaking us for a convoy of their own, but finding their mistake

they tacked about immediately. Our admiral hoisted a signal for a general

chase, and ordered the transports to lie to with one ship of the line and

two frigates.

The next morning about five o’clock we discovered our own fleet bearing down

very much increased, and soon after we had the happiness of being informed

of the capture of the enemy’s whole fleet, consisting of one sixty-four

ship, five frigates, and twenty-three sail of merchantmen, called the

Carraca fleet, all belonging to Spain, not one of them being able to escape

the vigilance of our brave British tars. The sixty-four is now in our

service and is known by the name of the “Prince William,” that young prince

being then on board the "Prince George” as midshipman, and an eye-witness of

the first grand stroke given to the united forces of France and Spain, then

joined against us. On the 10th January 1780 the 73rd Regiment was ordered to

serve on board the men-of-war on account of the vast number of prisoners

taken in the above fleet.

The troops being shifted, the prisoners properly secured, and everything

being got in readiness to pursue our voyage, we proceeded for Gibraltar. But

our enemies, being fully resolved to intercept us, again made their

appearance in a more formidable manner with twelve sail6 of the line on the

16th January 1780. About twelve o’clock they were observed, and at four in

the afternoon the two headmost of our ships, viz., the “Edgar” and the

“Bedford,” engaged them and resisted their fire for a considerable time

until some more of our ships came to their assistance, and then the

engagement became general. Just about this time the “St Domingo/’ a Spanish

ship of eighty guns, was blown up and every soul on board perished, to the

number of six hundred, among whom were many of the flower of Spain. In the

morning of the 17th victory declared herself on our side by adding to our

fleet five sail of the line, driving two on shore, and blowing up one, the

rest remaining shocking examples of British bravery. After the ships we had

taken were manned and the prisoners properly secured, we set sail and

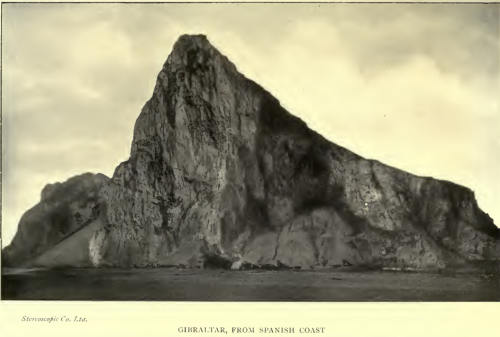

arrived in the Bay of Gibraltar on the 23rd of January 1780, having been for

some days driven by contrary winds behind the Bock, as far as Tetuan.

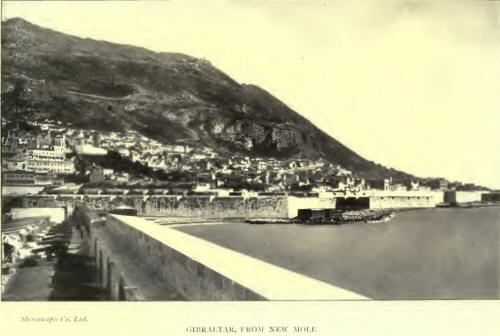

On the 29th January 1780 the 73rd Regiment landed at the New Mole and were

marched to Irishtown, a part of the town of Gibraltar so called. The

inhabitants for the most part having never seen a Highland regiment were

very much surprised at our dress, and more so at the bagpipes. At this time

all the necessaries of life were sold at an exorbitant price, and several

poor families were upon the brink of perishing before we came, but were soon

relieved by the supplies brought by the fleet. Soon after our arrival at

Gibraltar Colonel Mackenzie thought proper to send me to the hospital to

take care of the sick, under the direction of Mr Andrew Cairn-cross, head

surgeon of the regiment, an able surgeon and a humane gentleman, with whom I

continued during the time the regiment stayed in Gibraltar.

The change of climate and likewise of diet had such an effect upon our men

that a great many of them fell sick of the flux, of which numbers died. From

the beginning of the month of March to the end of June, we never had fewer

than one hundred or a hundred and twenty or thirty men sick in the

regimental hospital. Nothing material happened in the garrison till the 7th

of June 1780, when the enemy sent nine fire-ships under full sail from

Algeziras, about one o’clock in the morning, with the intent of burning our

shipping and navy stores, there being in the New Mole at that time over

twenty vessels. But by the vigilance of the “ Enterprize ” frigate and a few

more armed vessels lying in the New Mole, they were all towed round and no

harm sustained. The wood of the remaining parts of these nine ships proved a

good supply, as we were scarce of fuel at the time. We expected a

bombardment by land at the same time if their scheme had taken effect, for

Barcello, the Spanish admiral, had his squadron under sail to intercept our

shipping in case any of them should be under the necessity of quitting their

anchors and going to sea ; but contrary to his expectations all the attempts

proved fruitless, which he had the mortification to behold next morning upon

his return to Algeziras.

In the beginning of October

1780, the enemy began to break new ground in front of their new lines, and

carried on a line of communication between the old lines and their intended

new trenches, which line and trenches they completed in spite of all the

annoyance we gave them, although with considerable loss. The enemy continued

to work on the isthmus erecting batteries, notwithstanding our fire on their

working parties, who were often dispersed by our shells from Willis’ and

other batteries up the heights. At that time the garrison was very much

distressed for want of provisions: the troops were all put on short

allowance, and were paid the deficiency in money. The poor inhabitants7 were

in a much worse situation, having no other prospect than starvation before

them unless the place should be speedily relieved.

On the 12th of April 1781 the long expected English fleet made its

appearance in the Gutt very early in the morning, and as they came round

Cabrita point the enemy’s gunboats attacked some of the ships that sailed

close to the Spanish shore, but were soon obliged to retreat under shelter

of their batteries. But no sooner had the first ship cast anchor in the bay

than the Spanish opened all their batteries, firing with all the fury

imaginable both on the fleet and on the town—the latter they soon set on

fire with their bombshells, some of which fell into the inhabitants’ houses

killing and wounding diverse, others they threw as far as south shed-guard,

and a great many fell harmless among the shipping. The inhabitants fled from

the town to the south in the utmost confusion, exhibiting a most shocking

scene of misery, while the soldiery were for the most part plunged in the

deepest excess of riot, drunkenness, and plunder, notwithstanding the utmost

exertions of the officers.

The inhabitants were furnished with tents and formed a sort of camp near

Blacktown, where they afterwards built themselves huts with the wood the

ruins of the houses in town afforded. The troops then in town, viz., the

12th, 39th, 56th, and 72nd, together with three Hanoverian regiments, viz.,

Hardenburgh’s, Tteden’s, and La Motte’s, were ordered to the south, except

the 72nd, which was quartered in the King’s Bastion bomb-proofs. All the

rest were encamped on the face of the hill, all along from the end of the

south barracks to Europa Gate.

In the month of September 1781 the enemy began to fire from a battery

advanced a great way in front of their old lines, which annoyed us very

much, for they threw some of their shells as far as the Navy hospital and

our camp. This battery was named the Mill* battery. The governor, having

received some intelligence of the number of troops kept in this battery by

some deserters, thought a sally was practicable. Accordingly, on the evening

of the 26th November, an order was issued for all the wine-houses to be shut

up, and all the troops to repair to their different quarters, where they

were to remain till further orders. The 12th regiment and Hardenburgh’s,

with all the flank companies of the other regiments, were ordered to parade

on the Red Sands together with a detachment of the artillery, another of the

artificers, and about one hundred and fifty seamen. At twelve o’clock at

night they all sallied out through Landport, under the command of

Brigadier-General Ross; and no sooner had they passed Lower Forbes’ than the

Spanish patrols fired on them, but not minding them they advanced very

quietly. The patrols, however, alarmed the Mill battery; and they, thinking

that the whole troops of the garrison had sallied out, left their posts in

great confusion, while those that remained were all killed or taken

prisoner.

The artificers, being provided with materials and combustibles for setting

the battery on fire, soon had it in flames while the artillery were busied

spiking up ten mortars and eighteen pieces of cannon. The officer who had

the keys of the magazines was taken prisoner and obliged to deliver them,

and then the magazines were instantly blown up. Thus the great works which

cost the Spaniards so much labour and expense, taking eighteen months to

complete, were all totally destroyed in about an hour. This being done, the

troops returned to garrison in perfect order and without interruption, with

the loss of only four men killed, and one officer, two sergeants, and

twenty-two rank and file wounded, and one missing.

Two officers and ten men were taken prisoner, but one of the officers having

lost a leg died of his wounds on the 29 th December following. It was

computed that the Mill battery stood the enemy upwards of twelve million

dollars. The detachment that stormed and burned the above battery consisted

of 1 colonel, 3 lieutenant-colonels, 3 majors, 26 captains, 65 lieutenants,

14 ensigns, 2 surgeon’s mates, 144 sergeants, 3 drummers, and upwards of

2,000 rank and file.

On the 11th June 1782, a shell from the enemy fell into St Ann’s battery,

broke through a splinter-proof that covered a magazine door, burst open and

blew up the magazine, killing fourteen and wounding seventeen men.

We had different accounts by deserters that the enemy were preparing ten

large battering ships that were to be proof against shot and shell; these

battering ships were intended to make a breach in the wall and then the

enemy were to storm us. Accordingly, on the 13th September 1782, they

brought these ships to their moorings about half-past nine o’clock in the

morning, when a dreadful cannonading commenced from the land batteries of

the enemy as well as these ten battering ships, which they kept up very

briskly till four in the afternoon when we could observe them in confusion,

on account of their ships taking fire from our red-hot balls. When first we

began to fire at them our shot and shell rebounded from their sides and had

not the least effect, but having heated our shot in large stoves prepared

for that purpose, and taking a good aim, our artillery sent their red-hot

balls into their port holes, which having lodged in the opposite side by

degrees set them on fire.

They still kept up an incessant fire until eight at night, when they

slackened greatly, and at ten ceased firing entirely, their ships being all

on fire notwithstanding they had engines to quench it; but all their schemes

proving abortive, they made several signals for assistance to their fleet,

which lay at anchor at Algeziras. When about midnight boats came from the

fleet to carry away these poor wretches, the garrison fired grape among them

which must have done great damage; but two large boats full of men were

picked up, and some on rafts and broken pieces of timber. Very early in the

morning of the 14th Captain Curtis went with our twelve gunboats to save the

poor wretches that were left to perish in the burning ships, and took on

shore about four hundred including officers and men. Before noon they all

blew up one after another, with such a terrible shock that several doors and

windows were forced open and the whole bay was covered with wreckage.

On the 14th I was ordered to go with four men to bring a wounded man to the

hospital from upper All’s Well. Soon after they took up the wounded man a

shell was fired from the enemy which seemed to be directed to the place

where we were, and in escaping from it I fell over a rock, which hurt my

left side, thigh, and knee very considerably. I made shift, however, to get

the wounded man to the hospital. He soon recovered and was discharged fit

for duty, but my hurt was such that I never will get the better of it.

On the night of the 10th October 1782 the combined fleets of France and

Spain lay at anchor at Algeziras, consisting of fifty sail of the line. The

wind blew very hard and drove many of them from their moorings; some ran

ashore on their own coast, others lost their masts, &c. Very early in the

morning of the 11th we perceived a large ship displaying Spanish colours

within a few yards of our walls, and after we had fired a few shots at her

she struck. Captain Curtis went immediately on board of her and had her

moored as well as the weather would permit. The prisoners were instantly

brought ashore, consisting of about six hundred and fifty men besides

officers. The ship proved to be the “St Miguel” of seventy guns, and known

now in the English navy by the name of the “Gibraltar.”

That very evening the English fleet under the command of Lord Howe appeared

in the mouth of the Straits, but only a few light ships and some transports

came to anchor—the rest stood to the eastward. Next day the combined fleet

got under weigh and stood to the eastward likewise. A great concourse of

people of all ranks and denominations assembled on the different eminences

expecting a general engagement, but the combined fleet declined it. The rest

of our transports gave the enemy the slip and unloaded at the Rosia Bay; the

25th and 59 th regiments were also landed to reinforce the garrison, as also

some artificers and artillery, and drafts for the different regiments then

in the garrison.

On the 21st the British fleet, after completing what was their main design—I

mean the relief of Gibraltar—repassed the mouth of the Straits with the

combined fleet close behind. A running fight ensued off the Straits mouth,

but no ships were taken or destroyed on either side. Nothing of note

happened from that time to the 2nd of February 1783, when the firing from

the enemy ceased, and the following day a final period was put to this long

and tedious siege by a cessation of arms on both sides. And during the whole

siege I met with no other hurt than what I have already mentioned on the

14th September 1782.

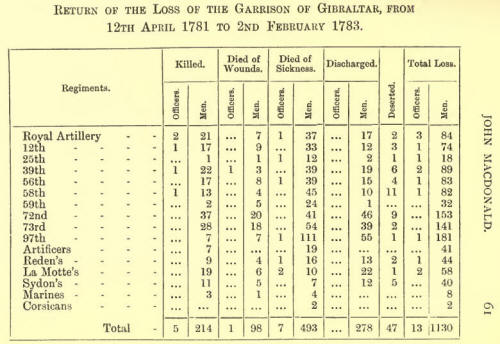

Being intimately acquainted with the clerks of the different regiments then

in garrison, I procured from them a complete return of their different

losses during the siege, which I have collected together as follows:—

After the conclusion of the

war the 73rd regiment was ordered to hold themselves in readiness to embark

for Britain in order to be discharged, and about the beginning of June 1783

an order was issued from the Government for all such as chose to enlist out

of the 72nd, 73rd, and 97th (being all to be disbanded) to enter into any

regiment they liked best. I being sensible that no provision had been made

for me at home, and having then no otherwise but to continue in the army,

agreed with the commanding officer of the 25th8 regiment to teach school in

the regiment for three years. This agreement took place on the 24th June

1783, but I did not give up the charge of the hospital till the 6th of July

following, which day the 72nd and 73rd regiments embarked for Britain.

That evening I joined the 25th and soon after set up school, which I

continued to carry on with good success, and was in every respect very well

used by the officers and the regiment in general. On the 24th of January

1784 I got the payment of Major Edgar’s company (the sergeant that paid that

company being discharged), and on the 13th February following the payment of

the light infantry company, to which I myself did belong. Both these

companies I paid until the 27th of February 1785, when I resigned the office

in consequence of an order from the War Office to discharge all three years’

men who did not choose to enlist for life, and to reduce the regiments to

two sergeants, three corporals, one drummer, and forty-two privates to each

company.

I being one of the number to be discharged, as being unfit for service and a

three years’ man too, left off keeping school in daily expectation of the

governor’s order to be sent home, but time slipped away without a word of

leaving the Rock. At last, on the 12th of June, Colonel Rigby, commanding

officer of the 25th regiment, thought proper to send me to take charge of

the regimental hospital, which I continued to do till the 14th November

following, at which time the reduction of the army took place in Gibraltar.

I was then discharged, and recommended in consequence of the hurt I received

on the 14th September already described.

Just at that time Sir George Augustus Eliott, Governor of Gibraltar, wanted

a butler, the old man who served him formerly in that capacity being quite

infirm and superannuate; and I being well recommended to the governor by his

steward,* with whom I was intimately acquainted, was immediately hired to

come to the family as soon as I had passed the

Board. On the 15th November 1785 all the discharged men were put on board

the “ Admiral Parker ” and “Jane ” transports, and sailing that same day for

England landed at Portsmouth on the 7th December, after riding six days’

quarantine at Mother-Bank. After four days’ stay at Portsmouth, I set out

for London, where I arrived on the 12th December. On the 22nd I passed the

Board, and on the 6th of January 1786 I received my first pension.

Having settled my little business in London, I waited very impatiently for a

ship for Gibraltar till the 6th of February, and that day went on board the

“ Mercury,” Captain Stocker, which sailed down the River Thames and landed

at Gibraltar on the 13th of March, after a tedious and dangerous passage of

five weeks. Immediately after landing I was joyfully received by my friend,

Mr Mackay the steward, and on the 17th March entered on the office of butler

to General Eliott, in which station I continued during his lifetime.

About the beginning of May 1787 General O’Hara arrived from England to take

the command of the garrison of Gibraltar, General Eliott being then called

home. The “Mercury,” Captain Stocker, being then in the bay, was hired to

take the governor and his family home; and having been fitted out for that

purpose and everything got on board, General O’Hara took the command on the

29th May, while General Eliott embarked that same day at the New Mole, and

setting sail immediately we were out of sight of Gibraltar in a few hours.

When we got out to sea the general turned sea-sick and went below to his

cabin, where he continued during the rest of the passage. We had a very

pleasant passage, arriving at Spithead on the 17th of June and the day

following came into Portsmouth harbour, where the general and his retinue

landed and proceeded to London, I being ordered to go round with the ship

and baggage to the River Thames. Accordingly, on the 23rd June we sailed

from Portsmouth, and on the 28th arrived at Horsley Down, but we landed none

of the baggage until the 7th of July on account of the press of business at

the Custom House. Having got all the baggage, &c., examined and passed at

the Custom House, I was ordered to land, and then went to the general’s

house at No. 21 Charles Street, Berkley Square.

On the 6th July 1787 General Eliott was created Lord Heathfield, and took

his seat in the House of Peers accordingly. I remained at my lord’s house in

town until the 12th of August, and then was ordered to a country house he

had taken at Brentford End, near Sion House, the seat of the Duke of

Northumberland, about seven miles and a half from Hyde Park Corner.

July 8th, 1788.—His lordship being in town was suddenly seized with a

paralytic stroke which almost immediately deprived him of the use of his

left side, from the top of his head to the sole of his foot. He was seized

at the door of his town house, and being helped into his carriage ordered it

to be driven to his country house immediately. He was for some days a little

delirious, which soon subsided into a settled sickness. About the middle of

September his lordship gave up the country house and lived constantly in his

town house—which was then at No. 21 Great Marlborough Street—for the

convenience of being nigh the physician who attended him.

In the beginning of March 1789 his lordship began to get a little better and

bought a large house with a garden and about twelve acres of pleasure

grounds at Turnham Green, five miles from Hyde Park Corner. His lordship had

a second paralytic stroke very soon after coming to this house, which

brought him very low, but he soon recovered a little strength and seemed

much inclined to go to Bath for the benefit of the waters. Accordingly, on

the 24th of March we set off for Bath and stayed there for two months.

Another servant and I daily attended his lordship to the Pump Boom and

bathing place during his stay there.

Having received some benefit by drinking the water and bathing at Bath, his

lordship ordered things to be got in readiness for a trip to the Continent

to try the efficacy of the waters at Aix-la-Chapelle in Germany. We set out

for this place in the beginning of June 1789, and having landed at Calais in

France we travelled through part of France, Flanders, and Brabant, and

arrived at Aix-la-Chapelle about the 12th of June. Soon after he took a

country house at a place called Kalkhofen, about a mile from the town, to

have the purer air. And from this place his lordship came every morning to

town to bathe and to drink the water. We stayed there until October and then

returned to his lordship’s house at Turnham Green, where we spent the winter

at home.

In the latter end of April 1790 his lordship applied to his Majesty for

leave to go to Gibraltar to take the command of the garrison, which was

granted to him infirm though he was, for he had often expressed a great

desire to end his days in the place where he had gained such immortal honour

and universal applause. We left England with an intention of going to

Gibraltar over land and arrived at Aix-la-Chapelle about the 12th of May.

Here his lordship attended the baths and water as before until the 5th July,

but that day he felt unwell and towards the evening grew worse. About ten

o’clock at night he was seized with a third paralytic stroke attended with

strong convulsion, and was at once deprived of speech and motion, in which

state he continued until one o’clock the following afternoon, when he

expired, 6th July 1790.

His lordship’s body was embalmed a few days after his death and conveyed to

England, when it was laid in a vault made on purpose in Heathfield Church in

Sussex,* on the 2nd September 1790, in the seventy-second year of his age.

After the death of Lord Heathfield, his son, the present lord, discharged

all his father’s servants, I among the rest.

I remained in London after being discharged from Lord Heathfield’s service,

and meeting with no employment to my liking my money began to grow low.

After a long and fruitless attendance on different gentlemen who gave me

promises of providing for me, I at last engaged with Captain Alexander Gray

of the “ Phoenix,” an East Indiaman, to go a voyage to India in the

character of a servant and to play the pipes occasionally. Accordingly, I

went on board, having rigged myself out for the voyage, and on the 4th April

1791 we left the Downs. On the 1st of May we cast anchor in Port Paya, in

the island of St Iago, belonging to the Portuguese. Two nights after we were

driven from our anchors to sea by a violent gale of wind, and very nearly

struck on a reef of rocks that runs out into the sea on the north-east side

of the harbour; it was twelve o’clock next day before we regained our former

station in the harbour.

After having taken in fresh water and such provisions as the island

afforded, we left St Iago on the 8th of May and, having a favourable wind

for the most part of the rest of the voyage, anchored in the roads of Madras

on the 4th August of that same year. The next day we landed all our

treasures and such passengers as were for Madras, together with three

officers and 220 recruits for the 72nd and 76th regiments. On the 7th August

we left Madras and proceeded to Bengal, and on the 11th were met by a pilot

boat off Balasore roads, which conducted us safely as far as Diamond harbour,

where we moored ship on the 13th and landed the rest of our passengers.

That same day Captain Gray went to Calcutta, and a few days later I and the

rest of the servants followed and lived constantly at the captain’s house in

Bond Street. We stayed in Bengal, sometimes ashore and sometimes aboard,

until the middle of October 1791, and then took on board 450 sepoys with

their officers, and a cargo of rice, paddy, gram, doll, and gee for the army

on the Malabar coast. It was near the end of October before we landed our

troops and cargo at Madras ; and Captain Gray, having a private property of

rice of his own, sent me to be a check on the black man who took an account

of it ashore. The captain had a house in Fort St George at which those on

shore always lived.

In the beginning of November we left Madras roads, and about 4 o’clock the

following morning, the ship being under a firm easy sail, we were overtaken

by such a sudden squall as had very nigh proved fatal to all of us. All

hands were instantly called up, but before the running rigging could be let

go we had scarcely a rag of canvas left. The wind was at that time a little

abaft the larboard beam with the sails braced forward, and the ship being

very light she heeled to starboard so far that we could not stand upon deck

without a hold. As soon as possible we bore away before the wind, set about

taking down the rags left us by the squall, and began rigging up others in

their place. With contrary winds we were three weeks coming to Bengal, and

at last reached Diamond harbour towards the latter end of November.

Having moored ship the captain and some passengers from Madras went to

Calcutta; next day I and the other servants followed. The ship at Diamond

harbour began to take in her cargo about the middle of December, and on the

25th dropped down the river as far as Cox’s Island, where we took in the

last of our cargo. On the 8th January 1792 we left Cox’s Island in the

kingdom of Bengal and proceeded for Madras, where we arrived on the 16th,

and after taking in some passengers and invalid soldiers to the number of

150, we left Madras on the 20th day of January and set sail for England. We

had very favourable weather till we were off the Cape of Good Hope, but were

baffled there with contrary winds for ten days: at last, having got into the

trade wind, we arrived at St Helena on the 3rd of April.

We stayed at St Helena for twelve days taking in water and fresh provisions,

and on the 16th April unmoored ship and set sail. On the 4tli June we

arrived safely at the Downs, where we landed some of our passengers, on the

next day proceeded to Gravesend, and on the 7th of June moored ship in Long

Reach.

At this time Lord Macartney with a large retinue was preparing to go upon an

embassy to China in the “Lion” man-of-war of sixty-four guns, and the

“Hindostan” East Indiaman was ordered for the same expedition to carry part

of his lordship’s suite, and a great many models and other valuable presents

for the Emperor of China. Having left Captain Gray’s service, I was at my

own request recommended by that gentleman to Captain William Macintosh of

the “Hindostan” to go the voyage with him to China. I agreed with Captain

Macintosh, and after buying such things as I wanted for the voyage went on

board the “Hindostan” then lying at Deptford on the 5th of July 1792, and in

a few days we dropped down the river to Gravesend. After taking on board

there the remainder of our cargo, some of my lord’s retinue and part of his

bodyguard, we set sail on the 3rd September to join the “Lion” at

Portsmouth, and after making a little stay at the Downs arrived at Spithead

on the 6th.

It took some time for my lord and his attendants to get in readiness, so

that it was the 26th September before we left Portsmouth, and the next day

we were met by a gale of wind that obliged us to put into Torbay till it

abated. On the 1st October 1792 we left Torbay with a favourable breeze in

company with the “Lion,” and on the 10th anchored in Funchall Bay in the

island of Madeira. We stayed at this place for some days to take in wine and

fresh provisions, and weighing anchor on the 18th arrived at Santa Cruz Bay,

TenerifFe, on the 22nd.

Some of the gentlemen of both ships landed on the island with a view of

exploring their way to the summit of the Peak of Teneriffe, but found it

impracticable after a fruitless attempt of three days, and were obliged to

return half famished with cold and wet. During the time the gentlemen were

ashore we had a very severe gale of wind which parted one of our cables and

obliged us to let down the sheet anchor; by this time we were within a

cable’s length of the shore, which if we had reached we must all have

perished, for nothing but the most dreadful rocks lay before us. The gale

having subsided a little we put to sea, and the next morning got the

gentlemen on board, this being the 27th.

Having got clear of Teneriffe we set sail for St I ago, where we anchored on

the 2nd November in Port Piya Bay; here we supplied the ships with fresh

water and some provisions, and on the 7th set sail for South America. We had

fine weather crossing the equinoctial, aud on the 30th November 1792 dropped

our anchor before the town of St Sebastian on the coast of Brazil, in South

America, but the “Lion” did not come in till next morning. This town or

rather city of Rio Janeiro belongs to the Portuguese, and is very populous

and wealthy. The inhabitants are very fond of buying showy things, such as

watches, trinkets, swords, fuzees, handsome horse - whips, pocket knives,

buckles, &c., for which in general they pay three prices, being very bad

judges and having plenty of money.

Here we stayed until the 18th September, such as had any merchandise going

daily ashore to traffic with the natives. We likewise took on board fresh

provisions, which were purchased very reasonably, and plenty of fresh water.

Both ships weighed anchor on the 18th December, and on the 1st January 1793

anchored at Trestiun de Cuchna, an uninhabited island claimed by no nation.

As it blew very hard we were obliged to weigh next morning, and on the 2nd

February came to another island called St Paul’s, likewise uninhabited. Here

we anchored and caught some of the finest fish I ever saw, and so fat that

they fried themselves. This island appears at night to be an entire volcano

with its lofty top all on fire. The gentlemen who were ashore declared upon

their honour that they had boiled a lobster in ten minutes in one of the hot

springs they found on the island.

Left St Paul’s on 3rd February, made Java Head on the 25th, and on the 1st

March anchored at North Island in the Straits of Sunda, between the Islands

of Sumatra and Java, one of the most unwholesome places in the world, I

believe. Here sickness and death began to rage in both ships. On 4th March

we left North Island and next morning anchored in Batavia roads. We took in

some fresh provisions and other articles at Batavia, especially arrack, a

liquor made here, very good when old but most pernicious to Europeans when

drunk new. We had a good many sick in both ships, particularly in the

“Lion”; and among the rest I had a fit of sickness which, though but of

short duration, had nigh hand carried me off. By the help of God, however, a

strong constitution and good attendance, I soon recovered so far as to be

able to do my duty, but never recovered my former strength while I stayed in

that country.

We lost several of our hands in this place, all young healthy-like men, but

making too free with the new arrack proved fatal to them. Batavia is so very

unwholesome that forty sail of merchantmen lay at moorings there for lack of

hands. Some had two or three on board, and a few had but one. The Chinese

carry on a great trade here.

We continued moving from place to place, from Batavia to North Island,

thence to Angrea Point, St Nicholas Point, Bantam, Onroost and Button

Island, all within the Straits of Sunda, until the 30th April, when we came

to anchor at the Nanka Islands, in the Straits of Banca, and there took in

wood and water. Anchored at Pulo Condore on 19th May, and the day following

had several accidents on board our ship in getting up the anchor. One man

had his thigh broken, another his arm, a third his knee-pan displaced, and a

fourth both his hip joints almost dislocated, besides several small hurts.

This was occasioned by the messenger parting between decks, and the men not

being able to hold on the capstan, it flew round with such velocity that all

the bars flew out in spite of all resistance and did all this damage. We

soon got a new messenger shipped, had the anchor up as soon as possible, and

on the 26th moored the ship in Turanni Bay, Cochin China.

We stayed at Cochin China till the latter end of June, then sailing away

passed the Laderoon Islands, and on the 1st July arrived at Chusan Bay in

China. On the 6th left Chusan Bay, anchored in Tinchufoo Bay on the 21st,

left on the 23rd, and on the 25th moored ship in Tientsin roads, out of

sight of land. On the 2nd August 1793 an order came from the emperor to land

all the gentlemen of the embassy and their baggage, &c., out of both ships,

for which purpose there came upwards of forty junks (as they call their

ships), with presents of live bullocks, hogs, sheep, and different sorts of

vegetables by the emperor’s orders for both ships. All hands were ordered to

work in shifting the presents for the emperor, &c., out of the ships on to

the junks, as our ships could not venture nigher the shore for sand-banks.

On 4th August 1793 Lord Macartney and all his retinue landed in the junks,

and Captain Macintosh being of the number, the command of our ship devolved

upon Mr Mitchell, our chief mate, a sober judicious, good man, and an able

officer. On the 6th August we left Tientsin, and about the latter end of the

month arrived again in Chusan Bay in company with the “Lion” We remained

here till the end of November waiting for the return of the gentlemen of the

embassy, and meantime got the ships fresh caulked, their rigging overhauled,

and everything ship-shape for the homeward bound voyage. At last, on the

27th November, Captain Macintosh and a few more came aboard, but Lord

Macartney and the rest of his suite went by land to Canton.

On the 30th November both ships left Chusan Bay with a fair wind, and

sailing close along shore among a parcel of small islands, our ship ran upon

a sunken rock. She did not rest upon it but she left her false keel behind

her. The next night there came on a most dreadful gale of wind which

continued for three days and nights without intermission; we were going at

the rate of eight knots an hour with bare poles, and towards the end of

December arrived at Wampoa, the anchoring place in the river about sixteen

miles below the city of Canton. On the 28th December Captain Macintosh went

to Canton, and a few days after I and the rest of his servants followed.

Here we had the first news of a war with France from the last arrived ships.

We remained between Canton and Wampoa until the 14th March 1794, and that

day, having got our cargo, passengers, and dispatches on board, set sail,

and on the 17th anchored at Maccoa in Portuguese territory. The next day we

left the roads of Maccoa, and by the 4th April arrived at North Island,

where we took on board wood and water for the homeward bound voyage in

company with the “Lion.” April lAth.—Both ships weighed anchor and Avere

joined by the China East India-men, to the number of eighteen, a Portuguese

ship, and an English whaler. The next morning we were out of sight of Java

Head, in all twenty-two sail. About the middle of June we were met by the

“Sampson,” of sixty-four guns, and the “Argo,” of forty-four, both ordered

by the Government to convoy home the East India fleet, and the next day we

made St Helena. We stayed about eight days at St Helena and were joined by

the Bombay, Madras, and Bengal ships; our fleet then consisting of about

thirty sail, including the three men-of-war. After passing the island of

Ascension we were met by a fleet of outward bound Indiamen, under convoy of

the “Assistance,” of fifty guns, which returned with us, and the East

Indiamen proceeded on their voyage.

August 18th.—We made Cape Clear in Ireland, and a few days after entered the

English Channel with a fine easy breeze, and on the 7th September arrived at

the Downs. I continued in the ship till the 13th, and then left her when the

captain’s property was all landed. Before I left China I laid out every

penny of money I could muster in different articles that I thought would

turn out to advantage, but these things being all contraband goods were

seized the moment we came to anchor by the Custom House officers, and then I

found myself almost destitute. To complete my misfortunes, when I went to

Chelsea for two years’ pension due me I found it stopped for being absent at

the time the pensioners were called in,9 when I was away in China. I made

application to the commissioners of Chelsea for redress, but to no purpose:

I was told that if I re-enlisted into any young regiment then raising I

should have my pension again when I should be discharged.

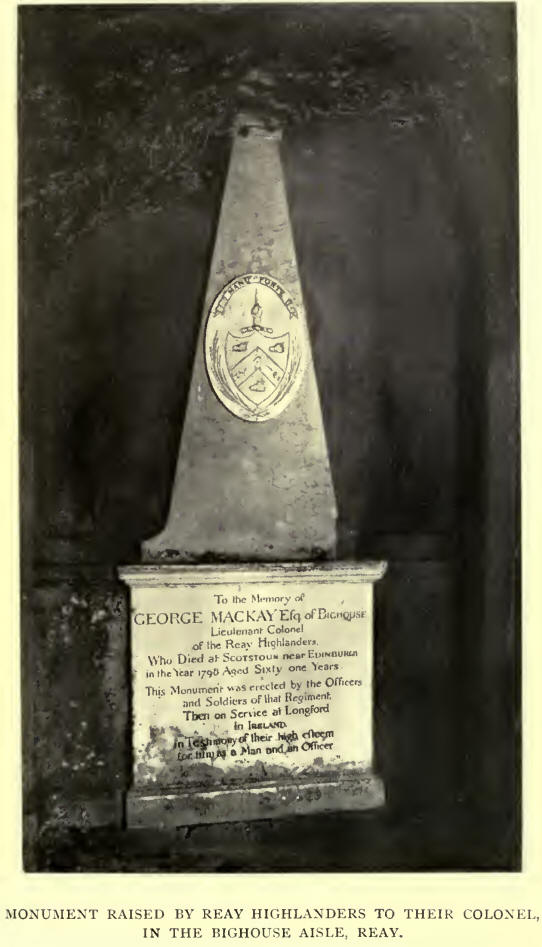

At that time Colonel Baillie* of Rose- ’ hall and Lieutenant-Colonel Mackay

of Bighouse were in London waiting for a Letter of Service to raise a

regiment of fencibles, which was obtained on the 24th October 1794, and on

the 27th I enlisted with Lieutenant-Colonel Mackay as pipe-major of that

regiment, which was afterwards called the Reay Fencibles. I stayed in London

with Lieutenant-Colonel Mackay till the 12th of November, then came with

himself to Edinburgh, and was left there with Lieutenant Munro and

Lieutenant Hunter of the same regiment, who were then recruiting for it in

Edinburgh and the country round. I continued on the recruiting service till

the 14th of April 1795, when the recruiting parties belonging to the Reay

Fencibles were called in to Elgin in Morayshire, which was our headquarters.

The regiment was embodied at

Elgin on the 17th of May 1795, and having received arms and clothing we

marched in two divisions to Fort George about the middle of July, where we

remained until the beginning of October, when we were ordered to Ireland.

Having left Fort George, we marched to Port-Patrick, were safely landed at

Donaghadee on the 3rd November, on the 5th arrived at Belfast, and were

there inspected by General Nugent, when a few men were rejected and sent

home to have their discharge. The regiment began to do duty then and

continued so to do till the 24th April 1796, when there was an order for

reducing all fencible regiments then in Ireland to 500. In consequence of

this reducement I was one of those discharged, on account of my lameness.

Having got my discharge from the Reay Fencibles, Lieutenant-Colonel Mackay

gave me letters to his lady and ordered me home to his own house at Bighouse,

to stay there till he returned to the country himself. Accordingly, all the

discharged men to the number of sixty-five marched from Belfast on the 25th

April, and the day following were landed at Port-Patrick under the command

of Lieutenant Hugh Clark, who returned to the regiment that same day after

settling with all the men before they landed. After landing, we began our

march for different parts of Scotland, I and the rest of the discharged men

from Lord Bray’s country directing our course for the north. We kept

together till we came as far as Badenoch, where I was taken sick and obliged

to keep to the king’s road, the rest taking a shorter cut to Inverness.

I arrived at Fort George very sick and much fatigued with travelling on the

10th of May, but my good old friend Mr Mackay, who was private secretary to

Lord Heath-field when I lived with him, and now an officer of invalides at

Fort George, would not let me go till I was fully recovered from my fatigue

and sickness. In short, I did not leave Fort George till the 24th May, and

on the 28th reached Bighouse, where I was very kindly received by the

colonel’s lady.* Soon after my arrival at Bighouse I was employed in

teaching the younger part of the children to read and write, and when

occasion required to superintend some outwork and to keep accounts.

I was extremely well used at the colonel’s house, but I wished for some

employment by which I might be more independent, as I considered myself one

who might well be spared, having no particular charge there. The colonel’s

lady wished very much that I should set up a school in her neighbourhood,

but the people could not give me proper encouragement, so it was dropped.

About the middle of October I received a letter from Mr Alexander Grant,

Falsaid, and Mr Donald Mackay, Kinside, two respectable farmers in the

parish of Tongue, inviting me to teach their children, as they were

acquainted with me before I left that country. I duly accepted their terms,

and having got a schoolhouse built began teaching on the 15th November with

upwards of a dozen scholars belonging to my constituents and the neighbours

around.

In the month of June following the parish school became vacant in

consequence of the schoolmaster being deprived of his reason, and on the 3rd

October 1797 I was engaged by the Rev. William Mackenzie and the leading men

of the parish to teach this school until a qualified man should be wanted,

or until I should be otherwise provided for. Accordingly, on the 15th

November I left Falsaid much against the will of my constituents, and on the

20th began teaching at Kirkiboll.

I continued teaching the school here until May 1800, with good success, but

being often told by Mr Mackenzie that Lord Reay wished to have a qualified

teacher in that parish in particular, I engaged to teach the parochial

school of Durness, the adjoining parish, and on the 15th May I left off

teaching at Kirkiboll to begin at Durness on the 20th, where I met with

every encouragement from Mr Thomson, minister of the parish, and from all

the other gentlemen in that place, who all contributed to augment my salary

and to render my condition as comfortable as possible.

At my first entrance upon business I boarded, but upon more deliberate

consideration I thought it best to marry, and having fixed my choice I was

married on the 22nd of July 1800 to a young widow whose former husband10 was

an intimate acquaintance of my own in the Reay Fencibles, and by whom she

had two sons. About the beginning of April 1801 there was a general call for

the out pensioners; those of Caithness and the county of Sutherland were

ordered to appear at Dornoch on the 30th of April and 1st May. In

consequence of the above order I appeared and was examined by a doctor, but

was returned unfit for garrison duty. A few only were ordered for garrison,

I think twelve only were kept out of 150 pensioners, the rest were all

dismissed and got at the rate of a penny a mile to carry them home.

On the 23rd of March 1802 my wife was safely delivered of a son, who was

baptised on the 26th and named James Mackay, after my worthy and benevolent

friend the late Mr Mackay of Skerray, as a token of gratitude for the many

favours conferred upon me by that gentleman and the rest of his worthy

family. And on the 29th of April 1804 she bare a daughter, who was named

Anne, after Mrs Mackay of Melness, daughter to Mr Mackay of Skerray.

In 1803 a Bill passed in Parliament for augmenting the salaries of parochial

schoolmasters, requiring at the same time that they should be qualified to

teach Latin. By this Act I was liable to be turned out of office as not

being qualified. I continued, however, to teach the parochial school of

Durness until 15th May 1806; but did not obtain the augmentation. In

November 1805 I engaged with Captain Mackay of Skerray to teach a school in

that district, the salary for which was to be paid by contribution. On the

17th April 1806 my wife was delivered of a daughter, who was baptised after

the name of Betty, for the deceased Mrs Mackay of Skail, sister of the

present Captain Mackay of Skerray, a worthy woman.

On the 21st May I removed with my family from Durness to Skerray, and on the

26th opened school there. Nothing worth mentioning happened until the 24th

of December 1807, when my pension was augmented from £7. 5s. to £12. 18s.

9d. a year by the interposition of Mr Hector Mackay, a gentleman of great

repute in London and who is well acquainted with some of the managers of

Chelsea College. It is true the pensions in general were augmented, but

those who served but a few years (as was my case) required some person of

distinction to represent their case. Otherwise they would be taken but

little notice of.

10 May 1808.—My wife was delivered of a third daughter, who was baptised on

the 14th and named Caroline, after the present Mrs Mackay of Skerray, as a

small tribute of gratitude due to that worthy lady for the many obligations

she has conferred on me and my family, and to which the present Skerray

himself has often contributed in a most obliging manner.

On the 20th May 1808 Captain Mackay was seized by a pain in the bones, which

he was subject to once or twice in the year. He struggled against it for two

or three days but was at last obliged to take to his bed, his sickness

having heightened into a nervous fever. He was sometimes thought to have a

cool bed, but as often relapsed. His greatest complaint was at first in his

bowels with a great compressure upon his breast, which continued till the

4th June when he complained of his head, the fever having taken another

turn, and on the 7th about 8 o’clock in the evening he died. Raising his

hands and eyes to heaven, the last words he was heard to utter were—“Holy,

holy, holy, Lord God of Hosts, who was and is, and is to come; grant that my

soul may have free admission into that glorious place, which I now behold.

That will do: I have now got the victory!” Having thus spoken he let his

hands down by his sides and, I trust, slept in Jesus.

The situation of his family at that time may be easier conceived than

described; his only sister and his three eldest children being so ill of the

fever that they could not be informed of his death, nor were they told of it

until some time after his funeral. Mrs Mackay bore all with a truly

Christian resignation although very low, having been brought to bed only a

few days before her husband fell sick. Thus died a gentleman greatly

esteemed by all who knew him, beloved by all ranks of people, generally and

justly lamented. He was one of the best of husbands, a tender parent, a kind

master. Humane, affable, benevolent, and of the most tender feelings, he

could see none in distress without relieving them if it were in his power.

About the same time an account of the death of Mr Hector Mackay, London,

appeared in the public papers, which happened on the 20th May 1808, and

would have occasioned great grief to all his relatives if it came at any

other time, but Captain Mackay’s death made such a wound in the heart of all

concerned that all other sorrow passed through unnoticed, except Mr Hector’s

own sisters who now must be inconsolable after the loss of so good a

brother, who was also a great support to them.

On the 12th June Captain Mackay’s remains were interred* with all the

solemnity due to his rank. His own company of volunteers fired three volleys

over his grave at the time of his interment. It was not till the 24th June

that his sister and children were so far recovered as to hear the account of

his death, when they were thought out of danger. Miss Jean, sister to the

deceased, on receiving the news of her brother’s death from the Rev. William

Mackenzie, minister of Tongue, was greatly agitated, but Mr Hugh, eldest son

of the deceased, a boy of fourteen years of age, behaved with uncommon manly

resignation ; the rest of the children were all more or less affected,

according as they were sensible of their loss.

The following account of Captain Mackay’s death appeared in the Edinburgh

Advertiser of the 24th June 1808:— “Died at Skerray, on the 7th June, in the

41st year of his age, John Mackay, Esq., Captain of the Volunteer company in

the parish of Tongue, deeply and justly lamented not only by his own family,

but by all within the circle of his acquaintance, being a gentleman of

sincere and unaffected piety, of the greatest honour, and strictest probity,

and who in discharging his relative duties shone with peculiar lustre.”

It may be thought by some that this digression from the narrative of my own

life is rather tedious, and that I have dwelt too long on the death of this

truly worthy man, but such as may think so little know the feelings of my

heart, having lost my only earthly friend and the chief support of my

helpless family. I never dreaded want so long as he lived, as he delighted

in the happiness of his subjects and always regarded the wants of the poor

and indigent. His attachment to me was uncommonly strong, having been his

own teacher when a boy and now teaching his children. The following poem was

composed by a neighbour friend, who was well acquainted with his life and

character from infancy:—

“Fain would my artless muse her tribute lend

To sing the grateful praises of a friend;

A faithful friend he was whose memory dear

From all that knew him claims the melting tear.

Yet not for him need tears of sorrow flow,

He now is far beyond the reach of woe;

But for the relatives whom he has left,

By early death of such a friend bereft.

No artful praises did his fame require,

The simple truth is all we need to hear.

All that the noblest genius could suggest

When said of him would be no more than just.

The Christian graces were in him combined

To all the pleasing charms of nature joined,

A noble aspect, and a graceful mien,

A solid judgment, and a mind serene.

The social duties were his special care,

In true affection none surpassed him there:

The fondest husband, and the parent kind,

The best of neighbours, and the constant friend.

All this he was, and more than I can tell,

But ah! he’s gone whom I had loved so well;

Cold death has called him to an early tomb,

In life’s full strength and youth’s meridian bloom.

To that bless’d land where such pleasures dwell

As thought conceives not or tongue can tell.

In this rejoice, fond partner of his heart,

Death hath no power but o’er his mortal part.

His precious soul hath reached a happier shore,

Where death and sorrow dare approach no more.

On Heaven’s all powerful aid repose your trust,

Although with grief’s corroding cares oppressed.

This pleasing hope should soothe your breast:

Tho’ you must mourn yet he is blessed.”

I continued in this place two years after the death of Captain Mackay, but

soon after that eventful period I felt the effects of the want of my patron,

and my school began to fall away considerably. Some of the grown-up boys

that attended my school enlisted into the army, some went to business; some

of the parents became regardless and withdrew their children, and others who

had children fit for school did not send them. At Whitsunday 1807 one of the

principal farms in the district was laid under sheep, and the people that

were there dispersed. The man who took it, having no children fit for

school, did not consider himself as interested either in me or the school.

My only support now was Mrs Mackay of Skerray, who always stood my friend in

time of need and often relieved my wants as often as she knew of them, and

that without any application made. Being naturally of a charitable

disposition, and knowing how much her worthy husband felt himself interested

in me, she never withdrew her kindness. Nor was I the only one that felt the

good effects of her regard and love to his memory, as I often knew her to

stretch a point to serve any of those whom she knew to be attached to him.

In March 1810 I consulted the minister of the parish about leaving the

district of Skerray, who agreed to my removing to the Melness side, another

district in the same parish, where a schoolmaster was wanted; and Mrs

Mackay, considering it would be better for me, gave her consent. She agreed

the more willingly as her second son James, who attended my school, was to

be sent to a Latin school, and her eldest son Hugh was at the University at

St Andrews. She likewise intended sending her eldest daughter to a

boarding-school at Inverness, so that her youngest daughter only could

attend my school; but the distance being rather far, the road bad and wet,

and the child but delicate, she could reap but little benefit from the

school, especially in the winter season.

Another inducement I had for leaving this place was that I could procure

very little sustenance for my family in it. Even potatoes I had to fetch

from the Melness side, the carrying of which cost me very dear

notwithstanding Mrs Mackay gave me the use of her boat gratis. This

difficulty I hoped to be freed from by removing to the Melness side, as they

rear and sell a great quantity of potatoes, and the land in general yields a

better crop than that of the district of Skerray. My stepson, Robert

Macpherson, enlisted in the 93rd regiment of foot in the latter end of

September 1809, and his brother Hugh followed his example in March 1810, so

that I was deprived of the only help I had, which rendered it the more

necessary for me to remove my family where I could procure the necessaries

of life near hand.

Accordingly, I agreed to go to Melness at Whitsunday after, and on the 15th

May got the most part of my furniture and my whole family carried by boat to

a place called Talmin on the Melness side, where the schoolhouse stands; but

there being no school kept in it since Whitsunday 1808, the roof of it was

entirely out of repair, and the people being busy with their labour could

only spare time to repair the principal room of the dwelling house in the

meantime. As the people were willing, however, the other room and the

school-room were soon repaired, and I commenced school in the beginning of

June. During the month of May and June this year, there was a great

mortality in this parish : no less than thirteen heads of families died in

that short space, besides some women. In short, all the counties of

Sutherland and Caithness were in a less or more degree infected by an

uncommon fever that swept away families, especially on the coast side of

Sutherland. Very few recovered of those that were seized, nor did the

greater part of those that died survive eight days, and some even died on

the third day after they were taken sick. The Almighty has been pleased to

bestow on me and my family a great portion of health during the time that

these fevers prevailed, for which we can never be thankful enough, although

some of our neighbours were called off the stage of life on all sides.

About the beginning of July the sickness abated, and health was restored to

a few who had been ill; and much about the same time the coast of Sutherland

and Caithness became more healthy. On the 9th April 1811 my wife was safely

delivered of a fourth daughter, and on the 17th, the mother being somewhat

recovered, the child was baptised Marion, in memory of the late Mrs Mackay

of Skerray, a gentlewoman of exemplary piety, hospitality, and charity. My

wife continued tender till about the beginning of June.

In the beginning of July 1815 I received a letter from the elder of my

stepsons, who had served as a grenadier in the 93rd Highlanders, informing

me that he was wounded in the right knee and had his right leg shattered by

a grape-shot on the 8th of January 1815, in the unsuccessful attempt against

New Orleans12 in North America, and was at the same time, along with some

others of the different regiments composing that expedition, taken prisoner

and robbed by the American soldiers while lying on the field of battle.

After all fruitless endeavours to preserve his leg he was obliged to undergo

the painful operation of an amputation on the 27th of March, and on the 24th

of June arrived at Hilsea Hospital, where he lay under cure when he wrote

me. He lay there until the 21st October, when he was removed to Chatham

where he remained till ordered to Chelsea to pass the Board on the 4th May

1816. His passage being paid by Government to Cromarty, he procured a

passage from thence to Thurso and from thence to this place, where he

arrived on the 28th May, after an absence of seven years and two months.

His arrival proved a great blessing to my family, for being naturally

adventurous and very industrious, as soon as he came home he set about

fishing or any other employment by which he might help the family; for

although he lost the limb above the knee he travels remarkably well with a

wooden leg, especially on even ground, and is very handy in a boat either in

rowing or sailing. He bought a share of a boat soon after he came home,

which proved very useful to us in such hard times, this year being the

dearest and scarcest ever known in this part of the country. In short, it

appeared to me an instance of the Almighty’s providential care for us, that

this lad came home at the critical juncture of time when we most wanted his

assistance.

He continued with ourselves until the beginning of December 1817, when he

went to teach a Gaelic school in the parish of Durness, and there continued

till the middle of March 1818 (the time for which he engaged), and on the

3rd of April was married to Catherine Mackay, daughter of the deceased Hugh

Mackay, in Hope.

About the break of day on Sunday, the 22nd of March, the roof of the

principal room in the house we occupied fell in, the couple having given

way, being old and rotten, but it pleased God that none of us were hurt.

There were five of us all asleep in the room at the time: when the couple

broke it came down gradually till it rested upon the top of the bed wherein

my wife and I, together with our youngest child, slept. The first crash it

gave wakened us so that we had time to escape to the next room.

The room remained in that ruined state until the 22nd of November following;

the people of the place, whose business it was to repair it, not being