|

There are several glens in the parish which possess

all the beauty and charm that result from a combination of wood and

stream and rifted rock, with the ever-changing light and shade that

afford such pleasure and delight to persons of a contemplative and

poetic nature. Of these, perhaps the finest is Killoch Glen. This

picturesque and romantic ravine is situated on the southern slope of

the Capellie range of hills, nearly opposite the town of Neilston.

Both its banks are finely wooded with well-grown trees, and it has

been celebrated in song as the early home of the crawflower,

anemone, and primrose. The glen is a comparatively short one, and

consists of two parts, the upper and the lower glens. The trap

formation at the top of the upper glen which separates it from the

hollow meadow-land beyond and to the west of it, bears evidence of

having been worn down by the overflow of water, probably from a lake

formed there by the ponded-back water of the Capellie burn that now

flows past the old mill and under the bridge on the Capellie road.

The upper reach of the glen is short but picturesque, and the

descent from the trap which separates it from the lower glen is

rapidly made by a series of broken rocks, and as the water plunges

over them a succession of foaming white falls is produced, which,

when the burn is in flow, have a grand appearance, especially when

viewed from below. Tannahill and his friend Scadlock have both sung

the praises of this truly delightful glen. In times of drought, when

the burn water is low, many pot-holes are observed in the bed of the

stream. In some places these have been worn into one another, giving

rise to many fantastic shapes, which have been from time immemorial,

in one way or another, associated with “The Witch of Killoch Glen.”

The smoother parts between the holes are her “floor,” and her

“hearth”; while the cavities, according to their shape and depth,

are her “cradle,” her “water-stoups,” and her “grave”; and it is

surprising how these objects are outlined in the part of the glen

referred to.

“Down splash the Killoch’s wimpling wave,

As through the glen the waters rave,

Far o’er the witch’s eerie grave,

Frae crag to linn,

Yon beetling rocks, they wildly lave,

Wi’ gurgling din.”

The Killoch burn, very shortly after leaving the

glen, as already stated, joins the Levern.

The Kissing Tree.—From Killoch Glen across Fereneze Braes to Paisley

there is, and has been from time immemorial, a footpath, or

right-of-way. From this path on the top of the hill on an early

morning in summer, when the sun’s rays are bursting athwart the

broad expanse below, one of the finest and most extensive views is

to be had of the surrounding country, a view which will well repay

the early riser for his trouble. Formerly the “Kissing Tree,” which

was well studded with nails, stood on the crest of the hill by the

side of this walk, connected with which tradition has it that the

swain who succeeded in driving a nail into its gnarled trunk at the

first blow was entitled to claim the osculatory fee. The tree has,

however, long since disappeared, carrying with it the nailed record

of many victories.

Midge Glen, or Image Glen.—This glen is inferior in beauty to none

of its size. In general contour it presents all the evidence of

having, through the ages, been scooped out of the trap formation

which forms its bed by the action of the river Levern. About

half-way through the. glen there is a sudden bend in it, the river

being turned from a nearly eastern to a nearly northern course, due

to the solid trap on the eastern hank, against which the water

impinges, having resisted its denuding power and deflected it from

its course. The river enters the head of the glen under a quaint old

bridge, immediately after leaving the “Links of Levern.” These links

are remarkable in the regularity and completeness of their formation

and in the way they wind about through the meado^-land above the old

bridge, in what is doubtless the silted up remains of an ancient

loch. Immediately on entering the glen, where it passes the ruins of

the old grain mill, the stream is dashed over a series of shelving

rocks which form two beautiful waterfalls. The banks of the defile,

especially the southern bank, as has been stated when dealing with

the Levern, are well wooded, and the “right-of-way” through the

glen, an old church path, is a delightful walk, as throughout its

course it overlooks the bed of the river, the waterfalls, and the

old mill. The walk seems to be much enjoyed by the people.

Polleick Glen.—This is a delightfully wooded glen, situated on the

outcrop of the carboniferous formations at the west end of the

village of Uplawmoor. It is not a long glen, but in its course there

are several fine waterfalls, and some charming “bits” from an

artistic point of view. The stream which flows through it rises in

Dumgraine moor and the meadow-land of Linnhead farm, and passes

under the bridge on the road leading from Uplawmoor past South

Polleick. On leaving the glen, it flows past Caldwell station and

joins the Lugton just immediately after the latter has left Loch

Libo.

Colinbar Glen.—This glen extends from Wraes grain mill to Arthur-lie

bleaching works, and has some fairly good wood on its banks. Kirkton

burn flows through it, and at its eastern end there is a pleasant

walk under the shadow of some trees.

Wauk-Mill Glen.—This glen reaches from the eastern or lower

reservoir of Gorbals gravitation works, at Balgray, to Darnley old

mill, a ruin on its right bank. It receives the overflow or service

water, which represents the continuation of the Brock burn, after it

has been ponded up, with other streams, in the reservoirs. Nature

has cut this glen through the outcrop of the carboniferous

formations of the Levern valley, the coal, clay, and lime-stone of

which are plainly visible on the northern side of the glen, where

they are being wrought by adit workings. The filters connected with

the reservoirs above are placed to the south of the glen, and

between them and the southern margin of the stream there is a very

agreeable walk, from the road leading from Barrhead to Upper Pollok

castle, through the glen to Darnley on the Glasgow Road. This ravine

is highly picturesque, being beautifully wooded with tall,

well-grown trees, under whose umbrageous shadows ferns of many kinds

grow in great luxuriance, and the stream murmurs in tranquil

solitude.

Evidence of Glaciers in the Parish.

That the valley of the Levern, like most of the great

valleys of Scotland, has been traversed by glacier ice during the

“great winter of our land” is amply borne testimony to by the

grooved markings left along the Fereneze and Capellie hill slopes

and alongside of Loch Libo on the exposed sandstone formation at

Uplawmoor wood ; and also by the famous inter-glacial beds in Cowden

Glen, and especially by the great glaciated surface on the

lime-stone formation at the Lugton outlet of the valley, in addition

to large sandbanks and gravel formations to the east of the loch and

at Killoch Glen, Gateside, and other places.

The direction of these groovings seems to indicate that the glacier

movements were in a north-easterly to south-westerly direction, from

probably what was the great ice field of our country at the time,

the dreary elevation of the moor of Rannoch. From the height at

which the markings can be traced on Capellie hills, the ice seems to

have quite filled the valley, and before denudition took place the

valley had probably more trap ash in it than at present. As the ice

age began to pass off and the rigours of the climate became

ameliorated, the valley glacier would seem to have been retarded in

its westward progress by the trap formations which so much narrow

the valley at the entrance to Cowden Glen, during which period the

sand, boulders, and boulder clay, were probably deposited—found in

such abundance in this locality as to suggest the existence of a

moraine.

When laying the sewage pipes from Levernbanks to Crofthead; and in

making the septic tank at Killoch Glen, great beds of sand had to be

dealt with, that at Killoch being quite stratified ; and everywhere

there were abundance of boulders. During operations for the

enlargement of Crofthead Thread Works some years ago, extensive sand

beds were also passed through. The cutting covered several acres,

and at the face the embankment had a depth of thirty feet. “At this

depth the sand was found to rest upon boulder clay, and this again

upon volcanic ash. But towards the surface the ash was found

interbedded with loose sand.” The boulders exposed during the latter

operation varied in size, many of them weighing several tons, and

requiring to be shattered with dynamite before they could be

removed. They were striated and non-striated, angular and

sub-angular, and many of them had travelled far.

In the course of constructing the Lanarkshire and Ayrshire Railway

in this neighbourhood, one of the cuttings passed through a

considerable extent of sand and gravel on Kilburn farm, evidently an

extension southward of the corresponding formations quarried for

many years on the adjoining farm of Holehouse. It was observed at

the time, that these deposits were laid down in such well-defined

stratified beds as to indicate the operation of water, probably some

ancient lake in the locality, which in some remote way had been

associated also with the valley glacier, ponding back the waters of

the higher lands, now the Levern, in the direction of Midge Glen,

where there is evidence that a much larger body of water once

existed than passes through it at the present day; at which time,

also, the natural channel of outlet for the stream would appear to

have been more easterly than the present course through Crofthead

mill.

It is quite in consonance with the existence of such

a lake, that some years ago, in a field on Holehouse farm, which

would then be covered by its waters, a beautifully finished,

evidently neolithic stone celt was found, which is in the writer’s

possession. A drain was being cut in one of the lower fields to

collect water for the supply of the then Holehouse laundry, during

an interdict of their supply from the Levern, and the celt was found

at an unascertained depth below the present land surface. In an

adjoining field was also found a stone sinker, or possibly a

whetstone. This stone is 5 inches long, by 2½ broad, and has a hole

through one end of it, which has been formed by drilling from either

side. The stone is in the writer’s possession. How long this lake

may have continued, there is nothing to indicate, but it most

probably existed well into neolithic times, when some primitive

savage or native, paddling over its surface, or possibly engaged in

the more deadly enterprise of war, lost the celt overboard, to be

subsequently restored to light by a modern drain-maker; whilst the

sinker, which the peaceful ploughshare revealed in long subsequent

ages, may have broken away from the primitive tackle. These

discoveries open up wide fields for reflection. The stone of which

the celt is made is “Water of Ayr-stone,” and as no such stone is

found in this locality, we have evidence of very early

trading—barter possibly, or possibly worse— or the celt may have

been part of the booty after some tribal battle with their

neighbours from the district of Ayr, and subsequently lost from the

canoe in the lake. As to the stone sinker, one can readily imagine

what grief the savage fisherman—not this time a disciple of honest

Isaac, but rather, a very early forerunner—would display when he

found that his tackle had given way, and the sinker it had cost him

so much pains and trouble to drill and make had gone to the bottom,

and was lost to him for ever.

The Lands and Properties of Neilston.

King David I., when he ascended the throne of

Scotland, was forty-four years of age ; of mature judgment, and

possessed of some education and refinement from his connection with

the Court of England, where his sister was Queen to Henry I. He was,

besides, a baron of England, and possessed large estates in that

country. His friends and followers from England were chiefly Normans

who came to settle in Scotland, as many of their fellow-countrymen

had done before during the reign of his father, Malcolm Camnore. By

them the feudal system, already established in England by the

Conqueror, and introduced into our country in the reign of

Alexander, became established, and from them most of the ancient

nobility of Scotland claim to derive their Norman descent. Prominent

among those who followed the king from England was Walter Fitz

Alan,— a scion of a Norman family in Shropshire, whose ancestor, the

first Walter, had come to England with William the Conqueror, and to

Scotland in the reign of Can more, to whom he acted as Dapifer. For

him the king seemed to entertain the highest esteem and regard, and,

for some eminent but unnamed special services, appointed him Lord

High Steward of Scotland —Senescallus Scotia?—an office which

afterwards became hereditary in that family. In addition to this

high favour and signal reward, and to enable him the better to

maintain his exalted position, large gifts of land were made to him,

including nearly the whole of what is now Renfrewshire, and much of

Ayrshire—King’s Kyle and Kyle Stewart in that county—lands which in

the beginning of the fifteenth century were erected into a Princedom

by King Robert III. for his son. Amongst the retainers of the High

Steward, who had accompanied him northward to Scotland in the king’s

service, was Robert de Croc, whose ancestors appear to have also

come to England with William the Conqueror, although there is an

opinion that he may have been of Saxon origin, from the prefix “de”

being seldom used in his name. Following the example of the great

Norman monarch, who had divided the rich lands of England amongst

those followers who had helped him in the great conquest, the

Steward would appear, almost immediately after receipt of the royal

honours and gifts from King David, to have begun sub-dividing them

with his retainers and followers, and accordingly, amongst the

earliest references there is to the lands of Neilston, The Register

of the Monastery of Paisley, circa 1170, shows that already these

lands, including nearly the whole of the parish, were in possession

of the ancient family of de Croc, whose principal residence was

Crookston, probably so called from the owner’s surname, the lands

being then named Crooksfeu. Subsequently to this date the lands of

Neilston passed into possession of a collateral branch of the same

illustrious family by marriage, when Robert Stewart, third son of

Walter, second High Steward of Scotland, took to wife the daughter

and heiress of Robert de Croc, designated of Neilston, as about the

twelfth century the greater part of the parish belonged to that

family. The lands of Glanderston formed part of the lordship of

Neilston, and, through the marriage of Lady Jane Stewart, also of

the High Steward’s family, with John Mure of Caldwell, they came

into the Caldwell family. John Mure of Caldwell disponed the lands

to his second son, William Mure (1554), in whose family they

remained until 1710, when the Mures of Glanderston, on the failure

of the elder line, inherited the Caldwell estates, and thus united

the lands of Glanderston to Caldwell again, after they had been

separated for a period of one hundred and fifty years. In 1774,

these lands were acquired by Speirs of Elderslie from Mr. Wilson,

and in that family they still remain.

In 1613, the Laird of Glanderston married Jean, daughter of Hans

Hamilton, rector of Dunlop. This lady’s brother, James, rose to

eminence in Ireland, being created first Viscount Clandebois, and

latterly Earl of Clanbrissil, honours which became extinct in 1798.

The Laird of Glanderston had issue by his wife, Jean

Hamilton:—William, afterwards Laird of Glanderston ; Ursula, who

became the wife of Ralston of that Ilk; Jean, who married John

Hamilton of Halcraig; Margaret, who became the wife of the minister

of the Barony Kirk, Glasgow. This somewhat eccentric clergyman,

Zachary Boyd, whose bust occupied a niche over the west arch in the

inner quadrangle of the old University in High Street, translated

parts of the Bible into a kind of rhyme, of which the following

quatrain may be taken as a specimen :—

“Jonah was three days in the whaul’s bellie,

Withouten fyre or caunill,

And had naething a’ the while,

But cauld fish guts to haunil.”

The MS. is in the College Library, Glasgow, but was

never published.

Lochliboside, the property of J. Meikle, Esq., of Barskimming and

Lochliboside.—This estate extends along the north side of the

valley, past Shilford, and joins that of Caldwell at Loch Libo, and

there is a charter to show that it was from an early period a

possession of the Eglinton family: “Charter by King Robert Second to

his dearest brother Hugh of Eglinton, knight, of the lands of

Lochlibo within the barony of Renfrew : To be held by Hugh and

Egidia his spouse, the King’s dearest sister, and their heirs,

Stewards of Scotland, for giving yearly ten marks sterling for the

support of a chaplain to celebrate divine service in the Cathedral

Church at Glasgow.” Dated at Perth, 12th October, 1374. In the

fifteenth century it was still an Eglinton possession, and became

pledged in a curious way as part of a marriage dower: “Indenture

between Sir John Montgomery, Lord of Ardrossan, and Sir Robert

Conyngham, Lord of Kilmaurs, whereby the latter ‘is oblgst to wed

Anny of Montgomery, the dochtyr of Sir Jone of Mungumry, and gyfe to

the said Anny joyntefeftment of twenty markis worth of hir mothers

lands.’ Sir John is bound to give Sir Robert for the marriage three

hundred merks and forty pounds, to be paid by yearly sums of forty

pounds from the lands of Eastwood and Loychlebokside.”

Neihtonside and Dumgraine lie to the south-west of the parish. A

large part of the property is rough moorland and marshes. During

some estrangement between Queen Mary and the Lennox family, we find

it treated as rebellious, and under date 36th April, 1548,—this was

before the death of Darnley, which took place on 9tli February,

1567,—“The Queen (Mary) granted to Robert Master of Sempile and his

heirs and assignees for services rendered by him, his friends and

relations, etc., the lands of Crookston (Crooksfeu), and

Neilstonside, also Inchinnan, with castles, towers, mills, multures,

fishings, etc., the advowsons of the churches, benefices of chapels

of the same, which fall to the Queen by their forfeiture of Matthew,

sometime Earl of Lennox.” In 1755, Neilstonside belonged to John

Wallace, a lineal descendant of Scotland’s great liberator, but is

now the property of Mr. Speirs of Elderslie. “The principal branch

of the Wallaces of Elderslie failing in the person of Hugh Wallace

of Elderslie, who died without succession. John Wallace of

Neilstonside was his heir.”4 There would appear to have been at one

time an old Celtic town of Dumgraine, near Waterside ; that the

castle of Walter Fitzallan, the first High Steward of Scotland,

appointed by King David I., circa 1140, was built at this place on

the south side of the Levern. (Semple.)

The lands of Fereneze are now the possession of Admiral Fairfax and

Auchenback, long a possession of the Earls of Glasgow, was purchased

some years ago by David Riddell, Esq., Paisley.

The estates of Capellie and Killochside are owned by A. G.

Barns-Graham, Esq., of Limekilns and Craigallion.

Chappell, the site of an early religious house attached to the Abbey

of Paisley, is the property of Joseph Watson, Esq., writer, Glasgow

and Barrhead.

But since the period of the early possessors of the lands now

enumerated, time has wrought enormous changes in the parish. In the

greater number of instances all that remains to show that these

ancient and noble owners through hundreds of years ever held

possession here, are a few ruins fast crumbling into oblivion, as

their owners have done long ages ago. Cowden Castle, which gave the

first title of Lord to the family of Cochrane, afterwards Earls of

Dundonald, is now a shapeless ruin on the hillside in Cowden Glen;

the lands of Lochlibo, at one time the property of the Earl of

Eglinton; Raiss Castle, east of Barrhead, in 1488 the property of an

ancient family named Logan, subsequently a possession of Lord Ross,

and afterwards of the Earl of Lennox, who granted it by charter to

Alexander Stewart, consang. suo, and of the family of Lord Darnley,

a son of whose house became the unfortunate husband and king to

Queen Mary of Scots ; the broad acres once owned in the parish by

the Earls of Glasgow,—have all changed hands, so that the motto,

“New men in old acres,” might very fittingly be applied to the

greater number of the proprietors of land in the parish of Neilston

at the present day.

Roads and Highways.

In few things have there been greater improvements in

recent times throughout the country generally, than in the condition

of the public roads that pass through parishes from one centre of

population to another ; and the parish of Neilston has participated

in this modern movement. The Romans—that mighty and intrepid

people—in the great military ways they constructed in their march

northward through Britain, were possibly the earliest road-makers in

our country; and their works have never been excelled for solidity

of construction. But it does not appear that the inhabitants

profited much by their example in road-making; and it was not until

Telfer and Macadam, the great engineers— especially the latter,

whose name is still preserved in the designation, “Macadamised

roads”—demonstrated the principles of road construction, that any

real improvement was effected in this direction. Before their time,

the roads were in such a wretched condition that travelling was

difficult and dangerous. We are told that in rainy weather there was

only a slight ride in the centre of the road, between two channels

of deep mud, and that, so late as 1669, the “Flying Dutchman”

stage-coach took thirteen hours to cover fifty-five miles, which was

considered a wonderful feat; and that even in the vicinity of the

Scottish capital the roads were such, that riding was always

preferred. When the military roads constructed by General Wade

through the Highlands made such a thing practicable, we learn that

his chariot, drawn by six horses, produced a great sensation in his

progress through the territory of the clansmen. It had been brought

from London by sea, and, when passing along the roads, the people

ran from their huts, bowing, with bonnets off, to the coachman, as

the great man, altogether disregarding the quality within. In those

days burdens were mostly carried on horseback ; and, to give the

animals secure footing and ensure them against sinking under their

loads, the roads in general were so made as to secure a rocky

bottom, and no attempt was made, by the slightest circuit, to avoid

steep places. For example, in making the old Glasgow and Kilmarnock

road, which skirts the southern border of our parish, the writer was

credibly informed by a gentleman of long experience as a road

surveyor, that the method adopted by Sir Hew Pollok, Bart., of Upper

Pollok, and the gentlemen associated with him in laying off the

undertaking, was to proceed to the top of one hill and then look out

for another in the direction they meant to go, and so continue; the

result being, that the road has a good and substantial bottom, but

is quite a “ switchback,” a constant succession of up and down hills

for much the greater part of its way, and therefore ill-suited for

vehicular traffic. So much was this found to be the case, as to

necessitate the construction of the “ New Line” of road some years

after, when the stage-coach had to be provided for. In our own

parish, where the Turnpike Act was long in being adopted (though

introduced into Scotland in 1750), the condition as regards roads

was nearly identical. The Kingston road to Kilmarnock being such a

“switchback” of hills and hollows, as to necessitate the building,

about 1820, of the new turnpike road from Glasgow, through the

Levern valley by Lugton, to Kilmarnock, Irvine, and Ayr, at a cost

of about £18,000. The parish roads at this period were even more

deplorable, before Statute Labour was converted into money payments,

in 1792.

Statute Labour Roads.

Formerly, the roads of the parish other than

turnpikes, being intended for local communication only, were kept up

by tenants, cottars, and labourers giving so much of their personal

labour yearly as served for their maintenance; the consequence of

this loose arrangement was, that not unfrequently they were allowed

to lapse into a very dilapidated condition. The writer remembers

being told by a Neilston farmer, that in his young manhood—the

beginning of the nineteenth century—in the parish of Kilmacolm,

where his father was also a farmer, he was sent with a load of hay

to near Govan, and that the condition of the roads was such as to

quite preclude the use of any kind of cart, and that the load of hay

had to be taken on the horse’s back. This, however, was a common

enough practice at the j:>eriod referred to in country districts,

and it is to this practice that we owe the term “load,” being just

as much as a horse could carry conveniently as a load of any

commodity. In the present day, to realize something of the condition

of such roads in our parish, it is only necessary to travel over the

relic of a reputed once public thoroughfare that passes from the

east side of Harelaw dam on the Moyne road, past Snypes farm to the

“Flush,” at the junction of roads from Barrhead and Neilston to

Mearns ; or the similar old road, the remains also of a once public

way, which passes along the top of the hill, by the farm of

Bank-lug, above Loch Libo, to Greenside and Dunsmuir road. But,

happily, these conditions are now gone, and by the Local Government

(Scotland) Act, 1889, the County Council now provides for the

maintenance of the highways, which include main roads and most of

their branches, everywhere throughout the parish, which, under the

superintendence of our vigilant surveyor, Mr. Robert Drummond, C.E.,

are kept in a thoroughly good condition ; while the bypaths, old

church roads, rights-of-way, and all roads other than highways, are

under the supervision of the Parish Council.

Toll Bars in the Parish.

Closely associated with the roads of the parish were

the tolls by which they were formerly kept up ; and, as this system

is now relegated to the limbo of past devices, not likely to be had

recourse to again, a few words regarding tolls may come to interest

those of a future generation who will know nothing of them from

practical knowledge. Toll primarily meant money paid for the

enjoyment of some special privilege or monopoly in trade. But

latterly it came to have a much broader meaning, and by Act of

Parliament, Customs of many kinds were recognised as

tolls—turnpikes, railways, harbours, navigable rivers and canals,

were all brought under its operation. Our interest, of course, rests

with the first of these, the turnpike, or road tolls. The first Act

of Parliament for the collection of tolls on the highways in

Scotland came into force, as already stated, in 1750. The principle

underlying this mode of taxation was, of course, “ that they who

used the roads should pay for their upkeep,” and at one period there

might have been a superficial sense of equity in this mode of road

upkeep, but after the introduction of railways, the whole position

was changed, and it soon became apparent that much injustice was

being practised on some branches of industry that others were

largely exempted from. For example, some large business concerns or

contractors, by the facilities railway stations afforded them, could

have quite a number of horses on the road from one year’s end to

another, and yet pay no toll ; while another contractor could not

move a load of coal from a pit, or stone from a quarry, without

having to pay toll dues on every cart. The toll bars were placed on

the turnpike roads by the Road Trustees, a public body empowered by

Act of Parliament to do so at their discretion; and they were

generally so placed as to intercept all horse or cattle or vehicular

traffic entering or leaving the parish, or passing through it. The

charges varied at different toll bars, but it is not apparent on

what principle, and vehicles varied according to the number of

horses by which they were drawn. At Neilston toll, on Kingston road,

the charge was 6d. for each gig and horse, 2d. for a riding or led

horse; Shilford toll the same ; Dovecothall toll the same; Kingston

toll was 4½d. for horse and gig, and l^d. for single horse; Dunsmuir

toll the same.

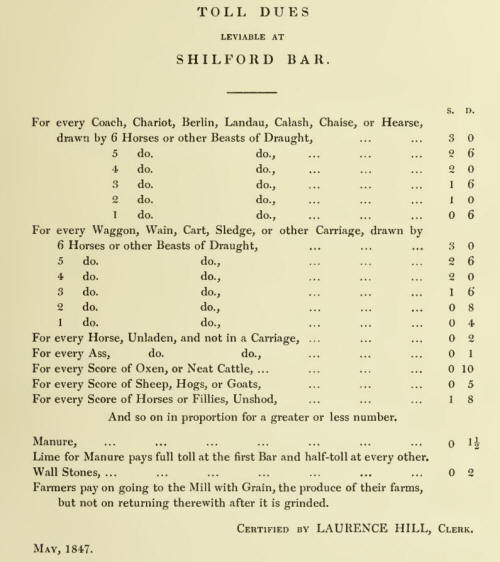

The following table indicates the dues leviable at most of the tolls

in the parish, a copy of which usually hung on a board outside the

tollhouse, for reference when the charges were disputed, as

sometimes occurred :—

The tolls were rouped annually, and, for our parish,

in Paisley. There was usually a dwelling-house attached to the toll

bar, in which the toll-keeper and his family resided ; gates, with

wickets for foot passengers at either end, were stretched across the

highway to intercept traffic ; and there was generally some one of

the family on the look out for traffic at night. This system of

collecting toll dues often entailed a considerable amount of

annoyance to the traveller ; as on a stormy winter day, or in a

hurricane of wind and rain in the middle of the night, when wrapped

up in waterproof or overcoat for protection—as was often the lot of

the country medical practitioner—it became necessary to strip to

procure the needful sixpence. But, happily, this clumsy mode of

tax-gathering is gone ; abolished by the “Roads and Bridges Act of

1878,” which came into force throughout Scotland, w here not

previously adopted, on 1st June, 1883. This arrangement applied,

however, to main turnpikes only; roads other than turnpikes being

dealt with under the Statute Labour Roads system until 1889, when

they were included as highways, and taken over by the County

Council. |