|

The parish of

Neilston, both in origin and name, is a very ancient one, and many

of the incidents connected with it date back to a remote antiquity

in the civil and religious history of our country. But,

notwithstanding this, objects of outstanding interest from an

antiquarian point of view are not numerous. The earliest objects of

this character are of ecclesiastical origin. Following on the

missionary enterprise of St. Columba to Iona in the sixth century,

it would seem that quite a number of monks from the monastic

establishments in Ireland came to different parts of Scotland, and

with great zeal entered upon the labours of converting and

civilising its early inhabitants. Of this number was St. Conval.

St. Conval’s Chapel and Well.

This saint was born

in Ireland in the fifth century, and came to Scotland in early life,

primarily as a disciple of St. Mungo or Kentigern, the patron saint

of Glasgow, and landed at Inchinnan on the Clyde. Strange stories

are told of his passage across the Channel—how, in the absence of

regular “shipping,” he was able by a miracle to transport himself

over on a boulder, which is still pointed out at Inchinnan as St.

Conval’s stone, and is credited writh powers of healing through

touch. He was eminent as a confessor, and patron of the churches of

Pollokshaws, Cumnock, and Ochiltree, and had many churches named in

his honour in other parts. Of this class was the very ancient

religious house situated at the primitive township of Fereneze, now

the lands of Chappell at Barrhead. Doubtless this early structure

was a very simple one, possibly at first only a votive cell of mud

and wattle, though in its later history becoming a church of greater

pretension and importance. In the sixteenth century the kirk lands

of this chapel were presented by Lord Semple as part of the

endowment of his collegiate church at Lochwinnoch. The lands of

Chappell lie immediately to the south of Fereneze hills, then

covered by forest; and it is a distinctive feature of this early

church “that its garden sloped back to the hills of Fereneze.” The

important question now is, Are there any relics of this church in

evidence? In the vicinity of the present mansion-house of Chappell

there exist certain substantial remains of a very early wall,

traditionally associated with the chapel of St. Conval. In the

opinion of the present proprietor, Mr. Joseph Watson, who has

investigated this matter thoroughly, these remains are most probably

relics of the boundary wall of the ancient church land, including

possibly part of the foundation of the ancient chapel. There is also

convenient to this mural relic a large dipping well, with abundance

of spring water, from which, it may be safely concluded, the

religious drew their water supply.

Our Lady’s Chapel of Aboon-the-brae,

and Lady-well.

About two miles to

the west of Neilston, on a plateau of the farm lands of Aboon-the-Brae,

overlooking Commore (the great valley), in which lie Waterside and

the Links of Leven, there formerly existed another of those early

religious houses, which, from its convenience to the great road

through Dumgraine Muir to Kilmarnock, has been conjectured to have

been most probably of the character of a hospice and monastery.

There are now no remains of this church visible above ground, but

within the memory of a gentleman still alive, the writer’s reverend

friend, Dean Tracy of Barrhead, certain remains of a pavement or

court were visible on the plateau referred to, such as are to be met

with in old Continental monasteries, by which it was almost possible

mentally to restore the outline of the ancient court of the hospice.

During the existence of Waterside Works, now razed to the ground,

there existed an old structure, little more than a gable partly

built into the other erections, which was out of all harmony with

its surroundings : for while the other windows were everywhere of

the ordinary quadrangular bleach work type, this gable presented

several shapely narrow lancet windows such as are characteristic of

ecclesiastical structures. Indeed, looking at them there was no

getting past the conclusion that the stones of this gable and these

windows had got into plebeian company, and that when Waterside was

being built, they had been brought from the then existing ruin of

the ancient religious house on the plateau of the farm above, hewn

and ready to the builder’s hand.

Many traditional stories have come down the ages from the old chapel

Aboon-the-Brae—such as the finding of hollow stones resembling

holy-water fonts, and, also, statues among the rubbish, by workmen

at different times, and especially of the image said to have been

thrown into one of the linns in Image (or Midge Hole) Glen.

At Aboon-the-Brae is also found the justly celebrated spring known

as the Lady-well, conjectured to have been one of the holy wells of

Scotland. This well has been elsewhere referred to in detail.

In the neighbourhood of Waterside, too, the first High Steward

erected a castle near the old Celtic town of Dumgraine, on the south

side of the Leveni, possibly a hunting seat, convenient to the

forest of Dumgraine, but no relic is known to exist.

ABTHURLIE STONE.

Within the grounds of

Arthurlie, at Barrhead, the property of Mr. H. B. Dunlop, D.L.,

there is a pillar stone of much interest and great antiquity, and

which in its day has passed through many vicissitudes. In its

original condition it is said to have stood in the field immediately

west of the present policies, a field designated the “ Cross-stane-park

” in the plan of the estate. Previous to 1788, there is good reason

for presuming that the structure was in this field and entire, base

and shaft, as it is stated that Gavin Ralston, in whose possession

the estate was at that time, had the upright shaft removed, and the

base on which it stood taken away. The base was spoken of as a

“trough stone,” from being hollowed out on its upper surface, where

probably the end of the shaft was fixed into it. There are said to

be historic grounds for thinking that the stone must have been

erected before 1452, but how much earlier is unknown. This very

ancient pillar is by some thought to be of Danish origin, and to

have marked the last resting-place of some venerated chief of the

name of Arthur; but by the majority of thinkers who have examined

it, it is considered to be much older, and associated in some way

with the memory of Arthur, the King of the Britons, the famous

“Knight of the Round Table,” and champion of many battles against

the Piets and Scots for the independence of the kingdom of

Strathclyde. This aspect of its history is more fully referred to

under “Arthurlie.” The stone is generally spoken of as “Arthurlie

Cross.” The material of which it is composed is a very hard and

compact sandstone, and the shaft is of the following

dimensions:—Height, 6 ft. 6 in.; breadth across the widest part of

the

base, 23 in.;

thickness at the same part, 9 in.; it tapers slightly towards the

top, where its breadth is 18 in. and its thickness 8 1/2 in. The

front and back surfaces of the stone are each divided into three not

quite equal panels, the middle one being the largest. The lower

panel of what is the north surface as the stone stands at present,

is surrounded by a flat moulding which is continued round the margin

of the stone, and divides it into three panels, the lowest of which

encloses a cross in slight relief. The shaft and arms of this

enclosed cross are respectively 3 in. and 2 in. wide, and are

entire, excepting that the lower part of the shaft seems shortened,

probably from the lower end of the stone having been broken at some

time, and possibly also from its base being set about a foot into

the stone on which it at present stands. The upper panels have no

cross, but are filled in with an intricate pattern of tortuous

interlacing rope work, very much after the manner of runic designs.

The pattern is boldly cut, and, considering the reputed great age of

the stone, is fairly well defined. What is now the south, or reverse

side of the stone from that we have just been describing, is also

divided into three panels, but this time more equally, and they are

defined by a rather obscure moulding and filled in with the same

interlacing pattern, blit there is no cross or other symbol. The

centre part of this surface is a good deal worn, and at one place

near the middle the pattern has been almost obliterated by the

tramping of many feet, a condition due to the fact that for many

years the stone did duty as a footbridge across the stream in

Colinbar Glen, at the bottom of “Cross-stane-park,” in which it had

stood originally. The edges of the stone show three panels, and are

traversed from base to top by a linked chain or rope pattern, the

members of which are about f-in. thick and well defined. At about

four feet up from the bottom of the stone, and in the middle of the

surface as regards its edges, there is an iron ring indented into

it, almost flush with the surface, and run in with lead, put there

to receive the end of an iron bolt when the venerable pillar did

duty as a gate-post at the entrance to a field, after its services

as a footbridge were over. But now, in its extreme old age, this

ancient relic has fallen upon better times, and once more stands

erect upon a double block of hewn sandstone at the end of a walk in

the garden, where it is carefully looked after by the present

proprietor, Mr. Henry B. Dunlop, the utilitarian age being past. But

it is doubtful if even now it is in proper position, as what is

presently the north surface should probably have faced the orient.

The top of the stone has been broken off at the point from which the

arms of the cross would spring, and the general appearance of the

shaft at present would indicate that, when complete, the cross would

resemble that cut in the panel on its front.

Capelrig Stone.

On the lands of

Capelrig, in a field to the north of the “Home Farm,” there is an

upright stone, very similar in appearance and general treatment to

that of Arthurlie; both are broken at the top; they are of the same

taper and composed of the same material, a hard sandstone; and as it

is probable that this stone is in its original position, it may

throw some light on the Arthurlie stone, which is certainly not so

at present, and is our reason for referring to it here. In the first

place, it is to be noted that the Capelrig stone is oriented—the

obverse surface to the east, the reverse west, and the edges north

and south—but the stone itself is not nearly so well preserved as

that at Arthurlie. Both surfaces are channelled from the top to

fully half-way down the shaft, as if long splinters had been burst

out of them by frost and exposure, and near the north edge of the

east face there is now a fissure as if the beginning of another

splinter. Both surfaces of the stone are divided into two nearly

equal panels, the dividing and border mouldings being 4 in. and 3

in. respectively. These panels have been filled in with some form of

figuring, possibly of an interlacing pattern, but it is so worn as

to be untraceable, and the pattern on the edges is similarly

obscured. There are no symbols or other specific forms on any part

of the surfaces. If this stone, as is assumed, is in its original

site, then it is flush with the ground, the grass growing rankly

round its shaft, and there is no visible trace of a base or trough

stone, as is claimed for that at Arthurlie. On separating the grass,

the base of the shaft seems packed round with stones, but it must be

set deep in the ground to give it the stability it evidently

possesses. Its measurements are:—Height, 6 ft. 4 in.; greatest width

at base, 30 in.; width at top, 20 in.; thickness at base, 14 in.; at

top, 12 in.

There are also preserved traditional accounts of the “Steed-Stane

Cross,” which, it is said, stood near “Rais Castle,” now in ruins,

at Dovecothall, Barrhead, and “Cross-stobs Cross,” which is alleged

to have marked the grave of the famous Donald Lord of the Isles, on

his defeat at Harelaw in the neighbourhood.

No relic of either of these two stones now exists; but Mr. Dunlop,

of Arthurlie, informed the writer that he remembered, many years

ago, seeing part of the stone from Cross-stobs lying behind the

hedge on the north side of the road leading by Hawkhead to Paisley.

These four stones,

Arthurlie, Capelrig, Steed-Stane Cross, and Cross-stobs, have been

evidently memorial structures and not wayside devotional crosses; a

view which tends greatly to strengthen the inference that

Neil’s-stone, which stood on Cross-stane Brae, was a fifth pillar of

the same character.

DRUID, OR COVENANTERS’ STONES.

On either side of the

footpath leading through the Moyne moor to the Long Loch there are

several stones of evidently considerable antiquity. They are seven

in number, and all lie in one direction, east and west. How they

came to be placed there, or for what purpose, is not known. They are

flat, undressed stones, with no inscription or other markings to

indicate their purpose. They have been variously called Druidical

and Covenanters’ grave-stones. The former they are not so likely to

be, but the latter is not at all unlikely, as they are quite in the

track of moor that leads by the south-west into Ayrshire by Lochgoin,

and we know that the suffering “Men of the Moss hags” during “the

killing time” were frequently in that district; and the further

fact, that it was by the Mearns moor route that a body of their

number marched to join the Pentland Rising, shows they were not

unfamiliar with the locality referred to. “The Covenanters of the

shire of Ayr, headed by several of their ejected ministers, whom

they had cherished in the solitary dens and hidings in the moors and

hills, to which they had been forced to flee from the proclamation

against the field-preacliings, advanced to meet us on our march,”

and “as we toiled through the deep heather on the eastern skerts of

Mearns Moor a mist hovered all the morning over the Pad of Neilston,

covering like a snowy fleece the sides of the hills down almost to

the course of our route, in such a manner that we could see nothing

on the left beyond it.”

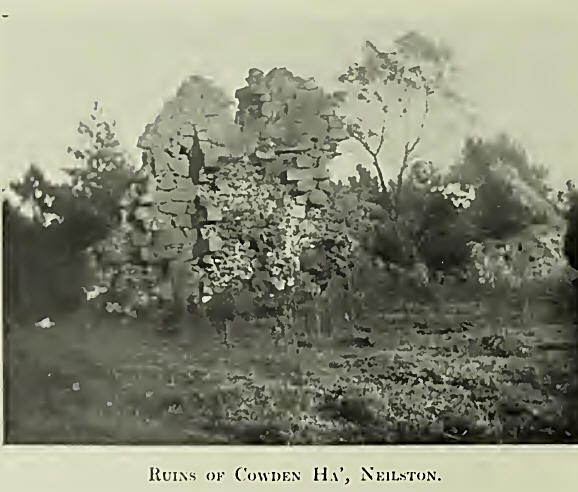

THE RUINS OF COWDENHALL.

The ruins of this

ancient castle occupy the summit of a rising knoll on the south bank

of Cowden Burn, about half a mile to the west of Neilston railway

station. When the “Joint Line” was being built, it became necessary

to alter the turnpike road here, and the hill on which the ruin

stands had to be cut down, on its northern slope; at which time also

the Cowden Burn was diverted from its natural bed, and made to run

in an artificial channel between the north side of the highway and

the line. To judge bv what remains of this ancient mansion, it must

at one time have been a place of considerable size and importance;

and that it was so, is quite borne out by the position accorded to

it in history. It is surrounded bv a number of line trees, ash,

beech, and plane, of quite forest dimensions, whose sturdy trunks

and mighty arms bear evidence of having wrestled with time, and not

unsuccessfully, for many centuries. Sir William Cochrane, afterwards

Earl of Dundonald, derived his first title of Baron Cowden from this

property.

The Spreuls of Cowden were a very ancient family in the parish.

Walter Spreul, who was High Steward of Dumbarton, Senescallus de

Dumbartoim, is the earliest of the family of whom there is any

record. He appears to have been a retainer of Malcolm Earl of

Lennox, from whom he had the lands of Dalquhern, pro homagio

servitio suo—for attendance and bodily service—referring to war

service, doubtless. This was early in the reign of King Robert the

Bruce, probably the beginning of the fourteenth century.

Subsequently to 1441, the property would appear to have been

alienated ; for in 1545 we find Queen Mary granting the castle,

etc., of Cowden to Spreul, for good services. {Reg- Mag. Sigilli,

1546-80.) The family, however, would appear to have failed in the

person of James Spreul, who sold the property to Alexander Cochran,

whose family, we have seen, afterwards became the Earls of Dundonald.

At a subsequent date, the estate became the possession of the

Marquis of Clydesdale, in right of his mother, a daughter of the

Earl of Dundonald. But on the Marquis becoming the Duke of Hamilton,

he sold it, in 1776, to the then Baron Mure of Caldwell, in which

family it still remains.

THE HALL OF CALDWELL.

This picturesque

building has already been referred to in the description of the

Mures of Caldwell, and it will be sufficient here to mention the

fact there dealt with in more detail: that at one period of its

history the property, under the name of Little or Wester Caldwell,

returned a Member to the Scottish Parliament, 1659, and that he was

paid for his services there by the Laird of Caldwell, as we learn

from “the Accounts” of that family.

Previous to the Covenanting times, “when the heart was young,” the

open green in front of the old Hall of Caldwell, we are informed,

was a favourite place for dance gatherings, and that the rival

followers of Terpsichore from Neilston, Lochwinnoch, and Beith, the

parishes adjoining this centre, had regular meetings for dancing

purposes and general enjoyment on summer Sunday evenings. On these

occasions there would, no doubt, be frequently witnessed the feats

of Goldsmith’s “Sweet Auburn,”

“The dancing pair that simply sought

renown,

By holding out, to tire each other down.”

Or that other picture

by Allan Ramsay, when describing similar meetings, in which—

“While the young brood sport on the

green,

The auld anes think it best

With the broon cow to clear their e’en,

Snuff, crack, and tak’ their rest.”

But with the advent

of the more earnest period referred to, those generally innocent and

happy meetings, that helped to while away the heavy hour— when books

were out of the question and reading to a great extent an unlearned

art—got naturally to be discontinued, and they are now merely matter

of very ancient memory.

GLANDERSTON HOUSE.

The lands of

Glanderston, in the beginning of the eighteenth century, were in the

possession of the Mures of Caldwell. Crawford, referring to the

mansion, in his History, speaks of it as a “Pretty one of a new

model, with several well-finished apartments, upon a small rivulet

adorned with regular orchards and large meadows, beautiful with a

great deal of regular planting.” This was in 1697, when it was

rebult, but “Ichabod” has long years ago been written over it ; its

glory has departed. But even in its ruin it was a picturesque old

structure, with crow-stepped gables and dormer windows with peaked

entablatures, and grass-grown gateway and court, with the initials

T.W. and W.M. carved in the lintel over the door, and the date 1697

over the windows. Its last occupant was Mr. Walton, and in it Mr. E.

A. Walton, R.S.A., was born about fifty odd years ago. Forty-five

years ago, the windows were gone and the door owned no latch, and

the wind and storm howled through the casements; but even then there

were several very interesting frescoes on the lobby walls—“A harvest

scene,” scenes of “Moonlight on the waters,” and others—possibly

where the R.S.A. “tried his ’prentice hand,” and if so, they were

certainly the promise of the distinguished artist of the present

day. But now they are gone, and the ruin even has been razed to the

ground, not one stone being left upon another to tell of its

existence. Further information will be found with regard to this

interesting old property under “the Mures of Glanderston.”

NEILSTONSIDE.

This property belongs

to Mr. Speirs of Elderslie, but it was at one time a possession of a

descendant of Sir William Wallace, Scotland’s liberator, whose

family removed to Kelly, in the neighbourhood of Greenock. A few

years ago, when some alterations were being made on the dwelling,

now a farm-house, the tradesmen came upon quite a number of old

Spanish silver coins of various values. But how they came to be

there, record says not.

CURIOUS PRESCRIPTION: A GLANDERSTON

RELIC.

For many years before

the Union of Scotland with England, “the predominant partner,” in

1707, the unsettled state of society and the country generally

offered a direct barrier to the advancement of all intellectual

pursuits; and witchcraft was only too often called in to account for

and explain what was not obvious on the surface. In these

circumstances, it is not very surprising to learn—what the following

ludicrous prescription abundantly shews—that the science of medicine

was at a very low ebb, and that empiricism not infrequently covered

want of knowledge. In any case, the prescription is sufficiently

curious in itself to merit notice, even if it had not been connected

with Glanderston in our parish. Dr. Johnstone was probably a

practitioner who had some status in Paisley. (The letter is from the

Caldwell Papers}

“Dr. Johnstoune to the Laird of Glanderstoun.

“Directions for Margret Polick. Paisley, Octr. 28, 1692.

“Sir,

“The bearer labours under the common weakness of being now more

feard yn is just. As she was formerlie a little too confident in her

own conduct. The spinal bon head hath never been restor’d intirly,

qch will make her sensible all her days of a weakness in a descent;

but will be freed from all achin paines if she nightly anoint it wth

the following oyl, viz. :

“Take a littl fatt dogg, take out only his puddings, & putt in his

bellie 4 ounces of Cuningseed; rost him, and carefullie keep the

droping, qrin boyl a handfull of earth wormes quhill they be leiklie;

then lett it be straind and preservd for use, as said is.

“My humble dutie to your Ladie. I am,

“Glanderstoun,

“Your most humble servitor,

“JOHNSTOUNE.”

LETTER FROM KING JAMES VI. TO THE

LAIRD OF CALDWELL.

The following letter

from King James YI. of Scotland to Sir Robert Mure of Caldwell, the

representative of the family at that period, and who had only

shortly before been knighted by him, is of interest, as reasonably

referring to Neilston parish, and also as shewing the personal care

the king took of matters now wisely left to the management of

ecclesiastical courts. The letter emanates from the royal palace at

Falkland, but does not record the year, but it was most probably

about the end of the sixteenth century, and consequently only

shortly before his accession to the throne of England, in 1603. The

diocese of Glasgow then probably extended westward to the parish of

Dunlop, where it became conterminous with that of Galloway, leaving

little doubt, therefore, that the “parochin” spoken of in the letter

as being “within your bondes” of Caldwell, was the parish of

Neilston, then under the care, as we have elsewhere seen, of Schir

David Ferguson, as curate.

“To our traist freind the Lard of Caldwell.

“Traist freind we greit zou weill. Undrstanding that our belovit

Robert Archbishhope of Glasgw is to repair and travell to the

visitatioun of all kirkis within the boundes of his dyocis, for

ordour taking and refor-matioun of abuses within the samyn according

to his dewitie and charge ; We have thairfoir thoucht gude, maist

effectuouslie to requeiste and desyr zou to accompany assist

manteine and concur with him in all thingis, requisit tending to

gude ordour and refermatioun of all enormiteis, within zour bondes

and parochin ; And to withstainde all sic as ony way wald seame to

impeid or hinder him in that hehalf; As ze will gif pruif of zour

gude aflectioun to our service and do us acceptable pleisour. Thus

we comit zou to God. From Falkland, the 22d day of July.

“James R”

THE TOWER OF THE PLACE OF CALDWELL.

This is another of

those relics that carry the mind back to an early period of the

history of the parish. The ancient “keep” is now in a good state of

repair, having been thoroughly strengthened by the late Colonel Mure,

M.P. It is situated on the summit of a hill overlooking the valley

of Loch Libo. The structure is a quadrangular or square tower, and

consists of three stories ; the walls are of great thickness, and

there are several windows and loop-holes in them. There are many

towers of similar character throughout the country; and, judging

from its style, it was probably built about the middle of the

fifteenth century. The kitchen, or ground flat, enters from the

court; the second flat is reached by an outside stair, while access

is gained to the third flat by a winding stair built in the

thickness of the wall; and the outside on the top, which is

surrounded by a battlemented parapet about three feet in height, is

reached through a hatchway or window in the roof. The ceilings of

all the apartments are built of stone, and vaulted, giving the

greatest strength to the erection. The present tower is but an

outwork of the original building, and in the palmy days of the

castle was connected with several other buildings, and a screen, in

such a way as to enclose a large court: the structures other than

the tower having been demolished during the forfeiture. Some of the

old trees of the avenue leading to the tower are still to be seen at

the top of the hill, the present turnpike road having been cut

through them; and, up till 1879, a number of their companions stood

in the field round the tower. Old and gnarled they looked, and

doubtless, from their elevated position, had wrestled with many a

storm in their younger days. But the hurricane wind-storm of that

winter— the winter after the Tay Bridge disaster—proved too much for

them, and they were all blown down, singularly enough, with their

heads all turned iu towards each other, as having been caught in a

whirlwind; and now the old tower stands alone.

THE OLD WINDOW IN THE CHURCH.

This ancient Gothic

window in the north side of the church is an object of much

architectural interest, which has already been referred to. Its age

is quite unknown, but the stone mouldings and general composition

would seem to point to a period not long after the foundation of the

religious houses, in the other parts of the parish, which were

holden of the Abbey of Paisley. The structure, as we learn from

Crawford, was gifted to the Abbot by De Croc of Crookston. It is

beyond doubt a preReformation relic; but what relation it bears to

that important event, whether of the church of De Croc, is

unascertained; most probably it is of mediaeval origin. The burial

vault of the Mures of Caldwell is situated under this window; and

during the many years this family was in possession of Glanderston,

they were patrons of the church. Referring to this place of

sepulture in 1640, on the occasion of making his testamentary

settlement, Robert Mure, the then Laird of Caldwell, directs,

amongst other things—“my body to be honestlie buryit, according to

my qualitie, besyd my predecessors in the kirk of Neilstoune.”

ANCIENT CROSS IN CHURCHYARD.

In the triangular

space between the walks in front of the church there is a most

interesting recumbent stone, having sculptured on its surface what

is considered to be an ancient Runic cross, all reference to which

is lost in obscurity.

STEWART RAISS.

Of this once

important castle only a very small part remains. The ruin is

situated at Dovecothall, on the south bank of the Levern, and

north-east boundary of the parish, and is remarkable for the great

thickness of its walls. In an assize connected with the lands of the

County in 1545, George Stewart of Raiss proved that the lands in

question at one time belonged to his kinsman, Matthew Earl of

Lennox; and Crawford tells us that he had seen a charter granted by

John Lord Darnley and Earl of Lennox, which puts beyond question the

fact that this property at one period belonged to that once powerful

family. |