|

CUNNINGHAM, ALLAN.—This

distinguished poet entered the world under those lowly circumstances, and

was educated under those disadvantages, which have so signally

characterized the history of the best of our Scottish bards. He was born

at Blackwood, in Dumfries-shire, 7th of

December, 1784, and was the fourth son of his

parents, who were persons in the humblest ranks of life. One circumstance,

however, connected with his ancestry, must have gratified the Tory and

feudal predilecting of Allan Cunningham; for his family had been of wealth

and worship, until one of his forefathers lost the patrimonial estate, by

siding with Montrose during the wars of the Commonwealth. A more useful

circumstance for his future career was his father’s love of Scottish

antiquarianism, which induced him to hoard up every tale, ballad, and

legend connected with his native country--a love which Allan quickly

acquired and successfully prosecuted. Like the children of the Scottish

peasantry, he was sent to school at a very early age; but he does not seem

to have been particularly fortunate in the two teachers under whom he was

successively trained, for they were stern Cameronians; and it was probably

under their scrupulous and over-strict discipline that he acquired that

tendency to laugh at religious ascetism which so often breaks out in his

writings. He was removed from this undesirable tuition at the tender age

of eleven, and bound apprentice to a stone-mason; but he still could enjoy

the benefit of his father’s instructions, whom he describes as possessing

"a warm heart, lively fancy, benevolent humour, and pleasant happy wit."

Another source of training which the young apprentice enjoyed, was the "trystes"

and "rockings" so prevalent in his day—rural meetings, in which the mind

of Burns himself was prepared for the high office of being the national

poet of Scotland. The shadows of these delightful "ploys" still linger in

Nithsdale, and some of the more remote districts of Ayrshire; and it is

pleasing to recall them to memory, for the sake of those great minds they

nursed, before they have passed away for ever. They were complete trials

of festivity and wit, where to sing a good song, tell a good story, or

devise a happy impromptu, was the great aim of the lads and lasses,

assembled from miles around to the peat fire of a kitchen hearth; and

where the corypheus of the joyful meeting was the "long-remembered beggar"

of the district; one who possessed more songs and tales than all the rest

of the country besides, and who, on account of the treasures of this

nature, which he freely imparted, was honoured as a public benefactor, and

preferred to the best seat in the circle, instead of being regarded as a

public burden. But the schoolmaster and the magistrate are now abroad; and

while the rockings are fast disappearing, the Edie Ochiltree who inspired

them is dying in the alms-house. May they be succeeded in this age of

improving change by better schools and more rational amusements!

While the youth of Allan

Cunningham was trained under this tuition, he appears also to have been a

careful reader of every book that came within his reach. This is evident

from the multifarious knowledge which his earliest productions betokened.

He had also commenced the writing of poetry at a very early period, having

been inspired by the numerous songs and ballads with which the poetical

district of Nithsdale is stored. When about the age of eighteen, he seems

to have been seized with an earnest desire to visit the Ettrick Shepherd,

at that time famed as a poet, but whose early chances of such distinction

had scarcely equalled his own; and forth accordingly he set off in this

his first pilgrimage of hero-worship, accompanied by an elder brother. The

meeting Hogg has fully described in his "Reminiscences of Former Days;"

and he particularizes Allan as "a dark ungainly youth of about eighteen,

with a boardly frame for his age, and strongly marked manly features—the

very model of Burns, and exactly such a man." The stripling poet, who

stood at a bashful distance, was introduced to the Shepherd by his

brother, who added, "You will be so kind as excuse this intrusion of ours

on your solitude, for, in truth, I could get no peace either night or day

with Allan till I consented to come and see you." "I then stepped down the

hill," continues Hogg, "to where Allan Cunningham still stood, with his

weather-beaten cheek toward me, and seizing his hard brawny hand, I gave

it a hearty shake, saying something as kind as I was able, and, at the

same time, I am sure, as stupid as it possibly could be. From that moment

we were friends; for Allan has none of the proverbial Scottish caution

about him; he is all heart together, without reserve either of expression

or manner: you at once see the unaffected benevolence, warmth of feeling,

and firm independence of a man conscious of his own rectitude and mental

energies. Young as he was, I had heard of his name, although slightly, and

I think seen two or three of his juvenile pieces."

"I had a small bothy upon

the hill, in which I took my breakfast and dinner on wet days, and rested

myself. It was so small that we had to walk in on all-fours; and when we

were in we could not get up our heads any way but in a sitting posture. It

was exactly my own length, and, on the one side, I had a bed of rushes,

which served likewise as a seat; on this we all three sat down, and there

we spent the whole afternoon; and, I am sure, a happier group of three

never met on the hill of Queensberry. Allan brightened up prodigiously

after he got into the dark bothy, repeating all his early pieces of

poetry, and part of his brother’s to me." . . . . "From that day forward I

failed not to improve my acquaintance with the Cunninghams. I visited them

several times at Dalswinton, and never missed an opportunity of meeting

with Allan, when it was in my power to do so. I was astonished at the

luxuriousness of his fancy. It was boundless; but it was the luxury of a

rich garden overrun with rampant weeds. He was likewise then a great

mannerist in expression, and no man could mistake his verses for those of

any other man. I remember seeing some imitations of Ossian by him, which I

thought exceedingly good; and it struck me that that style of composition

was peculiarly fitted for his vast and fervent imagination."

Such is the interesting

sketch which Hogg has given us of the early life and character of a

brother poet and congenial spirit. The full season at length arrived when

Allan Cunningham was to burst from his obscurity as a mere rural bard, and

emerge into a more public sphere. Cromek, to the full as enthusastic an

admirer of Scottish poetry as himself, was collecting his well-known

relics; and in the course of his quest, young Cunningham was pointed out

as one who could efficiently aid him in the work. Allan gladly assented to

the task of gathering and preserving these old national treasures, and in

due time presented to the zealous antiquary a choice collection of

apparently old songs and ballads, which were inserted in the "Remains of

Nithsdale and Galloway Song," published in 1810. But the best of these,

and especially the "Mermaid of Galloway," were the production of

Cunningham’s own pen. This Hogg at once discovered as soon as the

collection appeared, and he did not scruple in proclaiming to all his

literary friends that "Allan Cunningham was the author of all that was

beautiful in the work." He communicated his convictions also to Sir Walter

Scott, who was of the same opinion, and expressed his fervent wish that

such a valuable and original young man were fairly out of Cromek’s hands.

Resolved that the world should know to whom it was really indebted for so

much fine poetry, Hogg next wrote a critique upon Cromek’s publication,

which he sent to the "Edinburgh Review;" but although Jeffrey was aware of

the ruse which Cunningham had practised, he did not think it worthy

of exposure. In this strange literary escapade, the poet scarcely appears

to merit the title of "honest Allan," which Sir Walter Scott subsequently

bestowed upon him, and rather to deserve the doubtful place held by such

writers as Chatterton, Ireland, and Macpherson. It must, however, be

observed in extenuation, that Cunningham, by passing off his own

productions as remains of ancient Scottish song, compromised no venerated

names, as the others had done. He gave them only as anonymous verses, to

which neither date nor author could be assigned.

In the same year that

Cromek’s "Remains" were published (1810), Allan Cunningham abandoned his

humble and unhealthy occupation, and repaired to the great arena of his

aspiring young countrymen. London was thenceforth to be his home. He had

reached the age of twenty-five, was devoted heart and soul to intellectual

labour, and felt within himself the capacity of achieving something higher

than squaring stones and erecting country cottages. On settling in London,

he addressed himself to the duties of a literary adventurer with energy

and success, so that his pen was seldom idle; and among the journals to

which he was a contributor, may be mentioned the "Literary Gazette," the

"London Magazine," and the "Athenaeum." Even this, at the best, was

precarious, and will often desert the most devoted industry; but

Cunningham, fortunately, had learned a craft upon which he was not too

proud to fall back should higher resources forsake him. Chantrey, the

eminent statuary, was in want of a foreman, who combined artistic

imagination and taste with mechanical skill and experience; and what man

could be better fitted for the office than the mason, poet, and

journalist, who had now established for himself a considerable literary

reputation among the most distinguished writers in London? A union was

formed between the pair that continued till death; and the appearance of

these inseparables, as they continued from year to year to grow in

celebrity, the one as a sculptor and the other as an author, seldom failed

to arrest the attention of the good folks of Pimlico, as they took their

daily walk from the studio in Ecclestone Street to the foundry in the

Mews. Although the distance was considerable, as well as a public

thoroughfare, they usually walked bareheaded; while the short figure,

small round face, and bald head of the artist were strikingly contrasted

with the tall stalwart form, dark bright eyes, and large sentimental

countenance of the poet. The duties of Cunningham, in the capacity of

"friend and assistant," as Chantrey was wont to term him, were

sufficiently multifarious; and of these, the superintendence of the

artist’s extensive workshop was not the least. The latter, although so

distinguished as a statuary, had obtuse feelings and a limited

imagination, while those of Cunningham were of the highest order: the

artist’s reading had been very limited, but that of the poet was extensive

and in every department. Cunningham was, therefore, as able in suggesting

graceful attitudes in figures, picturesque folds in draperies, and new

proportions for pedestals, as Chantrey was in executing them, and in this

way the former was a very Mentor and muse to the latter. Besides all this,

Cunningham recommended his employer’s productions through the medium of

the press, illustrated their excellencies, and defended them against

maligners; fought his battles against rival committees, and established

his claims when they would have been sacrificed in favour of some inferior

artist. Among the other methods by which Chantrey’s artistic reputation

was thus established and diffused abroad, may be mentioned a sketch of his

life and an account of his works, published in "Blackwood’s Magazine" for

April, 1820, and a critique in the "Quarterly" for 1820; both of these

articles being from the pen of Allan Cunningham. The poet was also the

life of the artist’s studio, by his rich enlivening conversation, and his

power of illustrating the various busts and statues which the building

contained, so that it was sometimes difficult to tell whether the living

man or the high delineations of art possessed most attraction for many

among its thousands of visitors. In this way also the highest in rank and

the most distinguished in talent were brought into daily intercourse with

him, from among whom he could select the characters he most preferred for

friendship and acquaintance.

Among the illustrious

personages with whom his connection with Chantrey brought him into

contact, the most gratifying of all to the mind of Cunningham must have

been the acquaintance to which it introduced him with Sir Walter Scott. We

have already seen how devout a hero-worshipper he was, by the visit he

paid to the Ettrick Shepherd. Under the same inspiration, while still

working as a stone-mason in Nithsdale, he once walked to Edinburgh, for

the privilege of catching a glimpse of the author of "Marmion" as he

passed along the public street. In 1820, when Cunningham had himself

become a distinguished poet and miscellaneous writer, he came in personal

contact with the great object of his veneration, in consequence of being

the bearer of a request from Chantrey, that he would allow a bust to be

taken of him. The meeting was highly characteristic of both parties. Sir

Walter met his visitor with both hands extended, for the purpose of a

cordial double shake, and gave a hearty "Allan Cunningham, I am glad to

see you." The other stammered out something about the pleasure he felt in

touching the hand that had charmed him so much. "Ay," said Scott moving

the member, with one of his pawky smiles, "and a big brown hand it is." He

then complimented the bard of Nithsdale upon his ballads, and entreated

him to try something of still higher consequence "for dear auld Scotland’s

sake," quoting these words of Burns. The result of Cunningham’s immediate

mission was the celebrated bust of Sir Walter Scott by Chantrey; a bust

which not only gives the external semblance, but expresses the very

character and soul of the mighty magician, and that will continue through

late generations to present his likeness as distinctly as if he still

moved among them.

The acquaintanceship thus

auspiciously commenced, was not allowed to lie idle; and while it

materially benefited the family of Cunningham, it also served at once to

elicit and gratify the warm-hearted benevolence of Sir Walter. The event

is best given in the words of Lockhart, Sir Walter Scott’s son-in-law and

biographer. "Breakfasting one morning (this was in the summer of 1828)

with Allan Cunningham, and commending one of his publications, he looked

round the table, and said, ‘What are you going to make of all these boys,

Allan?’ ‘I ask that question often at my own heart,’ said Allan, ‘and I

cannot answer it.’ ‘What does the eldest point to?’ ‘The callant would

fain be a soldier, Sir Walter—and I have half a promise of a commission in

the King’s army for him; but I wish rather he would go to India, for there

the pay is a maintenance, and one does not need interest at every step to

get on.’ Scott dropped the subject, but went an hour afterwards to Lord

Melville (who was now president of the Board of Control), and begged a

cadetship for young Cunningham. Lord Melville promised to inquire if he

had one at his disposal, in which case he would gladly serve the son of

honest Allan; but the point being thus left doubtful, Scott, meeting Mr.

John Loch, one of the East India directors, at dinner the same evening, at

Lord Stafford’s, applied to him, and received an immediate assent. On

reaching home at night, he found a note from Lord Melville, intimating

that he had inquired, and was happy in complying with his request. Next

morning Sir Walter appeared at Sir F. Chantrey’s breakfast-table, and

greeted the sculptor (who is a brother of the angle) with ‘I suppose it

has sometimes happened to you to catch one trout (which was all you

thought of) with the fly, and another with the bobber. I have done so, and

I think I shall land them both. Don’t you think Cunningham would like very

well to have cadetships for two of those fine lads?’ ‘To be sure he

would,’ said Chantrey, ‘and if you’ll secure the commissions, I’ll make

the outfit easy.’ Great was the joy in Allan’s household on this double

good news; but I should add, that before the thing was done he had to

thank another benefactor. Lord Melville, after all, went out of the Board

of Control before he had been able to fulfil his promise; but his

successor, Lord Ellenborough, on hearing the circumstances of the case,

desired Cunningham to set his mind at rest; and both his young men are now

prospering in the India service."

By being thus established

in Chantrey’s employ, and having a salary sufficient for his wants, Allan

Cunningham was released from the necessity of an entire dependence on

authorship, as well as from the extreme precariousness with which it is

generally accompanied, especially in London. He did not, however, on that

account relapse into the free and easy life of a mere dilettanti writer.

On the contrary, these advantages seem only to have stimulated him to

further exertion, so that, to the very end of his days, he was not only a

diligent, laborious student, but a continually improving author. Mention

has already been made of the wild exuberance that characterized his

earliest efforts in poetry. Hogg, whose sentiments on this head we have

already seen, with equal justice characterizes its after progress. "Mr.

Cunningham’s style of poetry is greatly changed of late for the better. I

have never seen any style improved so much. It is free of all that

crudeness and mannerism that once marked it so decidedly. He is now

uniformly lively, serious, descriptive, or pathetic, as he changes his

subject; but formerly he jumbled all these together, as in a boiling

caldron, and when once he began, it was impossible to calculate where or

when he was going to end." Scott, who will be reckoned a higher authority,

is still louder in praise of Cunningham, and declared that some of his

songs, especially that of "It’s hame, and it’s hame," were equal to Burns.

But although his fame commenced with his poetry, and will ultimately rest

mainly upon it, he was a still more voluminous prose writer, and in a

variety of departments, as the following list of his chief works will

sufficiently show:—

"Sir Marmaduke Maxwell," a

drama. This production Cunningham designed for the stage, and sent it in

M.S., in 1820, to Sir Walter Scott for his perusal and approbation. But

the judgment formed of it was, that it was a beautiful dramatic poem

rather than a play, and therefore better fitted for the closet than the

stage. In this opinion every reader of "Sir Marmaduke Maxwell" will

coincide, more especially when he takes into account the complexity of the

plot, and the capricious manner in which the interest is shifted.

"Paul Jones," a novel; "Sir

Michael Scott," a novel. Although Cunningham had repressed the wildness of

his imagination in poetry, it still worked madly within him, and evidently

required a safety-valve after being denied its legitimate outlet. No one

can be doubtful of the fact who peruses these novels; for not only do they

drive truth into utter fiction, but fiction itself into the all but

unimaginable. This is especially the case with the last of these works, in

which the extravagant dreams of the Pythagorean or the Bramin are utterly

out-heroded. Hence, notwithstanding the beautiful ideas and profusion of

stirring events with which they are stored—enough, indeed, to have

furnished a whole stock of novels and romances—they never became

favourites with the public, and have now ceased to be remembered.

"Songs of Scotland, ancient

and modern, with Introduction and Notes, Historical and Critical, and

Characters of the Lyric Poets." Four Vols. 8vo. 1825. Some of the best

poems in this collection are by Cunningham himself; not introduced

surreptitiously, however, as in the case of Cromek, but as his own

productions; and of these, "De Bruce" contains such a stirring account of

the battle of Bannockburn as Scott’s "Lord of the Isles " has not

surpassed.

"Lives of the most eminent

British Painters, Sculptors, and Architects," published in Murray’s

"Family Library." Six Vols. 12mo. 1829-33. This work, although defective

in philosophical and critical analysis, and chargeable, in many instances,

with partiality, continues to be highly popular, in consequence of the

poetical spirit with which it is pervaded, and the vivacious, attractive

style in which it is written. This was what the author probably aimed at,

instead of producing a work that might serve as a standard for artists and

connoisseurs; and in this he has fully succeeded.

"Literary Illustrations to

Major’s ‘Cabinet Gallery of Pictures.’" 1833, 1834.

"The Maid of Elvar," a poem.

"Lord Roldan," a romance.

"Life of Burns."

"Life of Sir David Wilkie."

Three Vols. 8vo. 1843. Cunningham, who knew the painter well, and loved

him dearly as a congenial Scottish spirit, found in this production the

last of his literary efforts, as he finished its final corrections only

two days before he died. At the same time, he had made considerable

progress in an extended edition of Johnson’s "Lives of the Poets," and a

"Life of Chantrey" was also expected from his pen; but before these could

be accomplished both poet and sculptor, after a close union of twenty-nine

years, had ended their labours, and bequeathed their memorial to other

hands. The last days of Chantrey were spent in drawing the tomb in which

he wished to be buried in the church-yard of Norton, in Derbyshire, the

place of his nativity; and while showing the plans to his assistants he

observed, with a look of anxiety, "But there will be no room for you."

"Room for me!" cried Allan Cunningham, "I would not lie like a toad

in a stone, or in a place strong enough for another to covet. O, no! let

me lie where the green grass and the daisies grow, waving under the winds

of the blue heaven." The wish of both was satisfied; for Chantrey reposes

under his mausoleum of granite, and Cunningham in the picturesque cemetery

of Harrow. The artist by his will left the poet a legacy of £2000, but the

constitution of the latter was so prematurely exhausted that he lived only

a year after his employer. His death, which was occasioned by paralysis,

occurred at Lower Belgrave Place, Pimlico, on the

29th October, 1842.

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this chapter

here

Download this book here

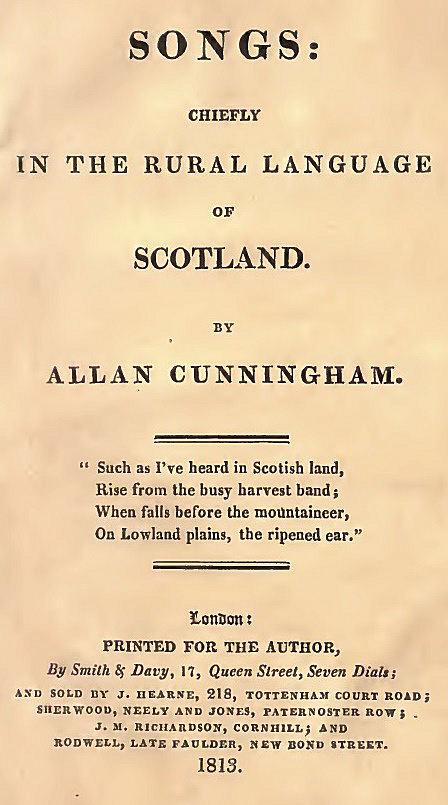

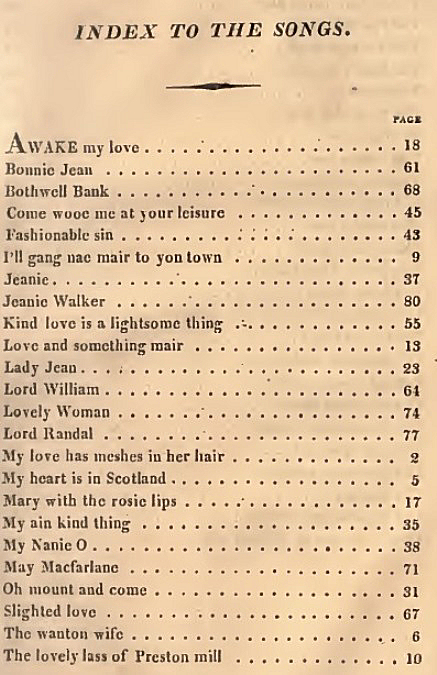

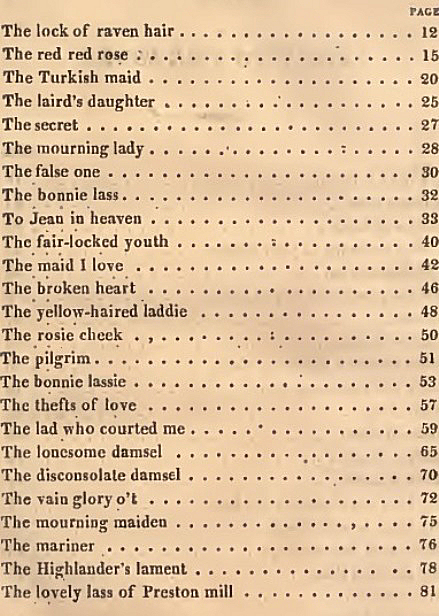

Songs: Chiefly in the Rural Language

of Scotland

By Allan Cunningham (1813)

Download this book here

Other Poems from his 1822 Book

Part 1 |

Part 2

The Songs of Scotland

In 4 volumes |