|

This is intended to be a

chapter of mosaics, for it contains many and parti-coloured fragments,

pieced together as skilfully as I can, relating to the scenery, people,

and traditions of my native county. The above heading has been chosen

because the dominant outward feature of interest in Caithness is the

almost continuous succession of lofty mural precipices which form the

coast line, and because the chief human associations, past and present,

of the county, lie along the rugged, rocky fringe of its shores.

This most northern county

on the mainland of Scotland has many peculiar, if not unique, features.

Occupying the north-east corner of the country, its form is rudely

triangular, though the lines are warped and curved by many a cape and

bay. The northern side faces the cold Arctic Ocean and the Orkney

Islands ; the eastern lies fully open to the wild storms of the North

Sea ; while the south-western border, touching these two at their

landward extremities and so completing the triangle, runs along the

waving line over moor and mountain, which divides the county from

Sutherland. On that boundary march there are elevated ridges toward

the north, and toward the

south clusters of mountains, some of which rise like cones or pyramids

over the low moorlands around. Apart from this more elevated strip along

the borders of Sutherland, the county of Caithness is for the most part

a widely-extended plateau, high above sea level, and varied over most of

its surface by shallow valleys and gentle undulations. The dreary and

almost treeless character of the interior, with its “moors and mosses

many o’,” has perhaps no attractions for the ordinary traveller; and

only certain parties, who have themselves come from beyond the

“herring-pond,” will agree with the American who said that Caithness was

“the finest clearance” he had ever seen. Yet there are many who ought to

take an interest even in the inland regions of the county. To the

geologist, for example, the Old Red Sandstone yields a plentiful crop of

fossil remains and other objects well worthy of his attention and study.

To the noble Hugh Miller, Caithness was a happy hunting ground from

which he gathered rich scientific spoils. Many remember the humorous

squib which was suggested by his rambles over the Old Red Sandstone,

“Tobacco and whisky cost

siller,

An’ meal is but scanty at hame ;

But gang to the stane-mason Miller,

He’ll pang wi’ ichth!olites yer wame ;

Wi’ fish as Agassiz has ca’d them

In Greek like themsel’s hard and odd,

That were baked in stane pies afore Adam

Gie’d names to the haddocks an’ cod.”

To the antiquarian and

historian also, every parish in the county offers a wide and rich field

for research. The cliffs and bays of the coast line are thickly studded

with ancient towers and castles. Their battlements and walls exhibit

every stage of ruin and decay, but the very winds which whisper and wail

around them are scented with romance. To an observant and curious eye,

even the tamest valley or barest ridge has something to show. Let any

one look at a full-sized Ordnance Survey map of Caithness, and he will

find it dotted all over, north, south, east, and west, with the

significant words in German lettering, “Picts Ho.” or “Picts’ Houses.”

These were the rude dwellings of the original inhabitants of the county.

In many cases the stones have been ruthlessly scattered, and the sites

torn up with the plough, yet not a few still remain in a wonderful state

of preservation. Some of these houses have been carefully uncovered and

examined, and have disclosed objects of interest and value which are

fitted to throw much useful light upon the old-world life of the

inmates.

These are outward and

visible features, but I cannot overlook one which is as real and

significant as any of them, though it makes no appeal to the eye of the

traveller. We have all seen old maps, on which the real or reputed sites

of battles are marked with tiny crossswords. If the same system were

adopted in the drafting of a map of Caithness, the significant signs of

old conflicts would be almost as numerous as Picts’ houses on the face

of the county. No wonder it might be so, for there is an ancient

couplet, often quoted to this day, which declares,

“Sinclair, Sutherland,

Keith, and Clan Gun,

There never was peace where these four were in.”

Here I must make bold to

repeat a question to which. I have never yet found or been offered an

answer. Why were the far-famed Mackays omitted from these lines ?

Certain I am that they did more fighting in Caithness than any other

clan except their traditional enemies, the native Sinclairs. Perhaps the

gifted poet could not squeeze an additional name into his line. On the

other hand the Guns, or Gunns, were not particularly prominent in the

strifes of these bloody days—at least not in Caithness—and their

omission from the couplet would do little wrong to history. That being

so, I venture to suggest that in future the couplet should run thus :—

“Sinclair, Sutherland,

Keith, and Mackay,

There never was peace when these four were nigh.”

If you search the old

clan records, you will find yourself perfectly bewildered with the

never-ending, ever-stirring tale of raid and rapine, duel and skirmish,

pitched battle and chronic warfare, of which these moors and valleys

were the arena for generation after generation. Thus has it come to pass

that it cannot safely be said of almost any twenty square yards in the

county, Here at least no foeman’s blood ever stained the soil. In

imagination, yet with almost no risk of error anywhere, you may sprinkle

the map all over with the fatal sign of the cross-swords.

There can be no question

that the coast scenery is the dominant feature of interest to the

traveller in Caithness. The petty tourist, who pays a flying visit to

Wick and Thurso and then declares he has seen Caithness, should be

banished south of the Grampians at once—to the Isle of Dogs if you like.

Meantime he may skip the rest of this paragraph, and of several which

follow. The northern shores from Drumholistan in the Reay country to

Duncansbay Head, and the eastern shores from Duncansbay Head to the

Orel, are overshadowed throughout five-sixths of their length, by mile

upon mile, mile upon mile, of brown cliffs, whose brows are firmly knit

against wind and storm, and relax not even in the sunshine. These rocky

flagstone walls have been built up in hundreds upon hundreds of

layers—some of considerable thickness, like tiers of actual

masonry—others thin and ragged like the uncut leaves of a book lying

upon the table. As an eminent authority has graphically said, “The faces

of the precipices are constantly etched out in alternate lines of

cornice and frieze, on some of which vegetation finds a footing, while

others are crowded with sea-fowl.” This iron-bound coast is withal

characterized by profuse diversity of detail. At close but irregular

intervals, the cliffs are cut from top to bottom by deep narrow ravines

called “goes” (pronounced gyoes, in one syllable), whose walls resound

with the breaking of the surf which heaves between them. Many and

marvellous also are the caves which open their ungainly mouths to the

tide and blast—some narrow and dark like the dens of wild beasts, others

with temple-like interiors of pillar and aisle and groined roof. Yet

again we note another feature of these iron defences against the ocean.

Detached from cliff or shore stand isolated masses of rock, called

“stacks”— some of equal thickness from base to summit, like broken

columns in the forum of Pompeii, others like elongated cones which taper

upward and point to the sky above. Without doubt they once formed part

of the sea-walls themselves, but storm and wave have cut them off from

their parent strata. Disinherited and lonely though they be, they still

stand erect and defiant in presence of the attacking foe.

In addition to many

smaller indentations of the sea, there are two wide breaks in the

rock-walls which are the fence and defence of the county. These are

Sinclair Bay on the east coast and the double bay of Thurso and Dunnet

on the north. With precipitous cliffs at their seaward extremities, they

are fringed with wide sunlit sweeps of yellow sand, where with arched

neck and curling mane may be seen

“The white steeds of ocean

that leap

With a hollow and wearisome roar.”

No one needs to be told,

and yet no one can fully realise, how dangerous and deadly this coast

has ever been to the “toilers of the deep,” sailors and fishermen alike.

Many a brave life has been quenched, and many a stout craft dashed into

fragments off these cruel heights. Over these things it is no shame to

drop a tear ; but not to all, nor at all times, have they been occasion

of grief. We are taught to pray “ for those in peril on the sea,55 but I

fear this was not always the spirit of those who dwelt on the Caithness

seaboard. To many, even in days not very long gone by, a wreck on the

coast was a godsend—a kind providence, for the chance of plunder was too

good to be foolishly despised or thrown away. We need not wonder that

this should be the opinion of any or every man who was a self-elected

and self-appointed “receiver of wreck!” There were in the good old days

many such native officials, and ofttimes they even quarrelled over their

individual rights and privileges.

As there were not a few

of this way of thinking in the far north, it will surprise no one to

learn that the erection of lighthouses oil our headlands and skerries

was not regarded with much favour. Many were not much concerned even to

hide or disguise their disapproval. One of these, a grim, northern

fisherman, expressed his mind slily but plainly enough to Mr Stevenson,

the noted lighthouse engineer. The latter had on one occasion hired a

boat to carry him somewhere on an errand of duty. As they sped along, Mr

Stevenson, in a tone of interest and sympathy, said to the boatman,

“How is it that your

sails are so poor and tattered?” The skipper was equal to the occasion,

for he replied with some emphasis,

“If it lied been God’s

mill that ye liedna built sae mony lichthooses, I wud hae gotten new

sails last winter.”

It is not likely that Mr

Stevenson pursued that line of conversation further; the boatman was

evidently not one who was very open to conviction on the subject.

Besides, all questions which lie on the border line between divine

sovereignty and human responsibility are full of risk and difficulty. It

would be wise on the whole to avoid controversy regarding them. One of

our modern poets goes so far as to suggest that the sea itself considers

it very good sport to hurl vessels on their doom and force the hot tears

of many a wife and mother. Does not Swinburne speak of

“the noise of seaward

storm that mocks With roaring laughter from reverberate rocks The cry of

ships near shipwreck ”

If the scenery of

Caithness is in many respects unique, so are the people, by which I mean

the great majority of the inhabitants. As to race and blood, they stand

out in bold relief from the natives of any other part of Great Britain,

but are closely allied to the islanders of Orkney and Shetland. You

remember how Daniel Defoe treats this subject in his famous cynical

piece, “The True-born Englishman,” a defence of William of Orange

against the race prejudices of his day. After enumerating the various

elements, Romans, Gauls, Saxons, Danes, Picts, and others, out of which

the English nation has been formed, he goes on to say,

“From this amphibious,

ill-born mob began

That vain, ill-natured thing, an Englishman.

The customs, sirnames, languages, and manners

Of all these nations are their own explainers :

Whose relics are so lasting and so strong,

They’ve left a shibboleth upon our tongue ;

By which with easy search you may distinguish

Your Roman-Saxon-Danish-Norman-English.”

The poet had good reason

to scourge such a mongrel people for their pretended or boasted purity

of blood ; but to the people of Caithness the reproach of mixed elements

scarcely at all applies. As briefly as possible let me try to tell their

story.

Who may have inhabited

Caithness or any other part of our islands in the days of Moses no one

can tell, and no one is the worse for his ignorance. We must come down

nearly to the beginning of the Christian era before we get into our

fingers any threads of fact regarding the early occupation of Britain.

One or two centuries before Christ, powerful tribes of Aryan origin

spread over Western Europe, and crossed over also to the British Isles.

Some say they came from Central Asia, some say from the northern slopes

of the Alps, some say from the southern shores of the Baltic, some say

from Africa and Spain; as to the actual whence, there is no real

certainty. They were, however, the Celtic branch of the Aryan family,

and after their settlement in Britain, were driven westward and

northward by the Jutes, Saxons, and Angles, who came after them from the

Continent at a later period.

One branch of the Celts

retreated into Wales and Cornwall, another possessed themselves of

Ireland, the Isle of Man, and the Scottish Highlands, even as far north

as Caithness. As for the old aborigines, few and weak as they probably

were, they must have been either extinguished or absorbed by the

invaders, who for all practical purposes may be considered the primitive

inhabitants of the country, at least in historic times. Thus the Celtic

hordes—to whom probably the name Picts or Picti first belonged, because

some of them painted their persons—occupied Caithness for some time

before, and for several centuries after, the birth of Christ. Then came

a great, though a gradual revolution, the beginning of which dates from

the year 780 or thereabouts. The Norse and Danish Vikings—so named from

their sheltering and skulking in the “viks” or bays—began to make their

savage descents upon the northern islands and counties of Scotland.

These sea-kings and their crews were for generations the terror of

Western Europe. Fearless alike either of storm or foe, they swept down

upon the seaboard of Caithness to ravage and destroy. Towns and villages

were sacked and burnt, and the inhabitants scattered, slain, or carried

into slavery. With graphic touch the poet thus pictures to us one of

these sea-kings,

“From out his castle on

the strand

He led his tawny-bearded band

In stormy bark from land to land.

“The red dawn was his

goodly sign,

He set his face to sleet and brine,

And quaffed the blast like ruddy wine.

“The storm-blast was his

deity ;

His lover was the fitful sea ;

The wailing winds his melody.

“By rocky scaur and beachy

head

He followed where his fancy led,

And down the rainy waters fled,

“And left the peopled

towns behind,

And gave his days and nights to find

What lay beyond the western wind.”

By-and-by the Vikings

entirely changed their policy and tactics. They came, not to raid and

depart again, but to remain and colonise. They acted the part of the

camel who asked room in a tent for his head, and then, forcing his whole

body in, dispossessed the inhabitants. The Norsemen founded settlements

here and there on the coast, and ere long pressed the old Celtic

inhabitants backward further and further into the interior. Thus did

they leave to the former possessors only a strip of country parallel

with the march of Sutherland-shire. Between the two races there was a

border land, but no fixed boundary stone. Even to this day we can

roughly define the extent and limits of the Scandinavian conquest and

occupation by the Norse names on the northern and eastern side of the

line, and the Celtic on the western and southern. To a keenly observant

eye the distinction is visible in the prevailing physical type, for

those of Viking blood may be known

“By the tall form, blue

eye, proportion fair,

The limbs athletic, and the long light hair.”

The contrast may also be

noted in the character and habits of the two races; and there are many

evidences of it in their language, and some even in their music. As to

the last named element, it is worthy of note, and may surprise some

people to know, that the bagpipe is rarely to be heard in Caithness. No

doubt it is an ancient and honourable instrument, for a high authority

has declared,

“And Music first on earth

was heard

In Gaelic accents deep,

When Jubal in his oxter squeezed

The blether o’ a sheep;”

but in the Scandinavian

county it is an exotic—an imported article from Sutherland—and little

esteemed by the sons and daughters of the Norsemen. As a consequence of

these statements I hope one excellent result will appear. We hear some

people, for whom we entertain the sincerest pity, express in very

vehement language their abhorrence of the bagpipe. In most cases this is

no more than a proud pretence, but they have now an opportunity of

proving their sincerity. If they like the north, but dislike the

bagpipes, let them go to Caithness, and the nearer to John O’ Groat’s

the better. As soon as this book is afloat, I shall expect to hear of a

great demand for summer lodgings in the county. Please avoid the towns,

however, for they are at times tainted with the Celtic musical element.

These statements

regarding the people of Caithness would hardly be considered up to date

were I to omit mention of two other circumstances. While the large

majority of the inhabitants are of Scandinavian blood, there does exist

a considerable Celtic element, due not so much to the remaining

descendants of the old race, but still more to the scores and scores of

families who were driven out of Sutherland early in this century by the

cruel policy of eviction. These very naturally settled for the most part

in the parishes nearest to their native county, among people many of

whom were of their own blood and language. Of Saxon blood also there are

undoubtedly some traces among the families of Caithness. Methinks I now

hear some ignorant Southerner express his wonder that any one of Saxon

lineage, and therefore knowing better things, should wander and settle

so far north, even for gold or for love. It might be sufficient to reply

that his wonder will not diminish either the fact or its significance.

But we have a better instrument of retort within reach. In this

connection I cannot resist the temptation to refer to a common reproach

and a delusion connected therewith. It has sometimes been said in the

south that “no fools come from Scotland,” because those who in point of

fact leave Scotland show themselves wise by so doing. That being so, the

number of Scotsmen who have found their way to England is supposed to

be, to say the least of it, remarkably large. Now I have a nice little

fact to offer as a gift to our English friends. It is asserted, and has,

I believe, been proved, that in proportion to the population of the two

countries, there are more Englishmen resident in Scotland than Scotsmen

resident in England. It is sometimes quite delightful to make that

statement to a typical John Bull, and to watch its effect. If that dose

appears not to be sufficient, you may add this other, that, according to

the same proportion, Scotland is, when tested by taxation, the richest

country in the world. One can take a malicious pleasure in driving these

points home upon the class of “ small ” southerners, if they are at all

disposed to crow over “poor Scotland.”

Had space permitted, I

might here review the formative influences, such as natural scenery,

social conditions and institutions, history, and religion, which made

the Norsemen what they were, and have to so large an extent moulded the

people of Caithness into what they are. With a bare and simple statement

I must pass from that tempting theme. As compared with the Celts and the

Saxons, the sons of the Vikings are characterised by restless energy,

sturdy independence, singular adaptability, and frank generosity. When

we remember that the inhabitants of our whole eastern seaboard, from

John o’ Groat’s at least as far as the mouth of the Humber, are tinged

with the same blood, we can understand how great has been the Norse

influence in the formation of the British character, and how many and

manifest its results in our national history and development.

Here I might be tempted

to indulge at some length in a dissertation on the origin and fortunes

of the family— for, strictly speaking, it should not be a clan—to which

I have the honour to belong. These are matters of quite peculiar

interest to me, but I have at least one good reason for reticence and

brevity. So far as the far past is concerned, I should scarcely be able

to say much to the credit of my ancestors. Even were I able to produce

evidence of high character and noble deeds on the part of some of my

“forbears,” I should be checked by the salutary warning that

“They who on glorious

ancestry enlarge,

Produce their debt instead of their discharge.”

The truth is that my case

very much resembles that of Sydney Smith, of whom some one inquired as

to the decease of one of his progenitors. In reply, the humourist made

the significant confession, “ Well, he disappeared suddenly at the time

of the assizes, and we asked no questions.” If not quite so dark as is

hinted at in these neatly-chosen words, the history of the Sinclairs is

for the most part a record of rapine, blood, and strife, and any little

traits or incidents of a more pleasing kind are only

“rari nantes in gurgite

vasto.”

It is said that on one

occasion Columba, the noble missionary of Iona, was asked to invoke a

blessing on a warrior’s sword. He responded in the remarkable words,

“God grant that it may never drink a drop of blood.” Not for many

generations was such a prayer uttered, or at least its burden fulfilled,

in the case of a Sinclair’s sword. They fought with every clan who dared

to claim an inch of soil in Caithness, and appear at more than one

period to have possessed the whole county. They were, however, most

unfortunate when they ventured on expeditions far away from home. How

wofully unfortunate they were, the more prominent chapters in their

history will show! I shall only mention two instances.

The first of these takes

us back into the early part of the sixteenth century. James IV. of

Scotland had quarrelled with his brother-in-law, Henry VIII., and set

out with a large army for the invasion of England. The Scotch army

encamped upon the hill of Flodden, and on its northern slopes was

fought, in 1513, the blackest battle in the annals of the northern

kingdom. William Sinclair, Earl of Caithness, and 300 of his men were on

the right wing of James’s array, and even after others had fled from the

scene of disaster fought to the bitter end. It almost looked like the

extinction of

“The lordly line of high

St Clair,”

for the Earl fell on the

field, and seareely a man— perhaps not one at all—returned to tell the

tale. When leaving home on that fatal occasion the Sinclairs had worn a

green uniform, and had crossed the lofty ridge of the Ord, the southern

boundary of the county, on a Monday. Ever since it has been an unwritten

law that no one of the name should ever wear that luekless colour, or

eross the Ord on the same unpropitious day of the week. Well might the

Sinclairs of Caithness at that date join in the pathetic lament,

“Dool for the order sent

our lads to the Border,

The English foranceby guile wan the day ;

The Flowers of the Forest that fought aye the foremost,

The prime of our land lie cauld on the clay.

“We’ll hae nae mair liltin’

at the ewe milkin’,

Women and bairns are heartless and wae ;

Sighin’ and moanin’ on ilka green loanin’,

The Flowers of the Forest are a’ wede away.”

The second great

misfortune to the Sinclairs took place about a century later, in 1612,

during the war of young Gustavus Adolphus against Norway and Denmark.

Colonel George Sinclair crossed to Norway with a force variously

estimated at from 300 to 1400 men, but most probably about 900, with the

intention of finding his way over the mountains to Sweden. These troops

were levied “on the sly,” and the “root of all evil” was not wanting in

the project. The Scotch king and government did what they could to

prevent its execution, and threatened that the leaders would be “put to

the horn,” that is, declared to be outlaws after three blasts of the

horn at the cross of Edinburgh. When Sinclair and his men landed in the

Romsdal Fiord; they met with unexpected and serious resistance. They

were attacked in a narrow defile in Gudljrandsdalcn by large bodies of

the peasantry, who, at a critical spot, hurled great masses of rock down

upon them. Colonel Sinclair fell among the rest, and at least half his

men were slain. Next day upwards of 100 more were put to death ; and

only some eighteen escaped with their lives. A monument on the high road

below the scene of conflict marks the grave of the leader, who was a son

of John, the Master of Caithness, of whom we have by-and-bye an even

more tragic story to tell. The people of Norway are proud of their

victory over the Sinclairs, and it has frequently been made the subject

of song. Here are the first and last verses of a free translation of one

of these ballads :—

“To Norway Sinclair

steered his course

Across the salt sea wave,

But in Kringelen’s mountain pass

He found an early grave.

To fight for Swedish gold he sailed,

He and his hireling band :

Help, God; and nerve the peasant’s arm

To wield the patriot brand.

“Oh many a maid and mother

wept

And father’s cheek grew pale,

When from the few survivors’ lips

Was heard the startling tale.

A monument yet marks the spot

Which points to Sinclair’s bier,

And tells how fourteen hundred men

Sunk in that pass of fear.”

In justice to my

clansmen, I must here take leave to repel an insinuation, and also to

correct an error. In some accounts of the fatal expedition, and

especially in a ballad by one called Storm, the Sinclairs are

represented as having burnt and plundered wherever they went. They are

even accused of having slain children at their mothers’ breasts. All

this is absolutely untrue. One Envold Kruse, a local stadtholder,

reporting officially on the subject, says, “ We have also since

ascertained that those Scots who were defeated and captured on their

march through this country, have absolutely neither burnt, murdered, nor

destroyed anything/' Again, in the last verse quoted above, the number

of Colonel Sinclair’s band is stated at 1400 men. Space would fail me to

enter fully into a discussion of these figures. This, however, after

careful and exhaustive investigation by competent authorities, may be

held as proven, that the Caithness men cannot have been more than 900 at

the utmost, and that 500 is probably nearer the correct figure.

As a foil, though but a

partial one, to these stories of disaster, it may be well to note one of

the Sinclair chiefs, who was a distinguished patriot and soldier. This

was Sir William Sinclair, who played his part so bravely at the battle

of Bannockburn that King Robert the Bruce, in acknowledgment of his

valorous exploits, presented him with a beautiful sword. On the broad

blade was inscribed this legend: “Le Roi me donne, St Clair me porte,”

i.e., The king gifts me, St Clair carries me. At a later date, the

gallant knight again showed his devotion to his monarch. Before he died,

King Robert charged

Lord James of Douglas to

have his heart embalmed, carefully borne to the Holy Land, and finally

deposited in the Holy Sepulchre. After the king’s decease, Sir William

Sinclair was one of the knights who set out with Douglas on his pious

errand to Palestine; but he fell, as Douglas himself did not very long

after, in an encounter with the Moors in Spain.

Before coming to more

modern times and more civilised ways, let me here insert two weird old

stories, the scenes of which are in different parts of the county. One

at least of these is undoubtedly founded on fact, though over what is

true not a little that is mythical and imaginative has grown, like the

lichen on the lettering of an old tombstone. It is neither my business

nor my intention to attempt to disentangle these elements; and,

therefore, I shall present the traditions just as they have shaped

themselves in my memory, after somewhat careful inquiry and study.

The first, and perhaps

the more doubtful of these, which I shall make also the briefer, is a

story of the Bruan coast, some ten miles south of Wick. Nowhere, even on

the Caithness seaboard, are the rocks and caves and goes more

fantastically wild and imposing. Only those who have sailed along

beneath their shadows know their varied and marvellous attractions. It

is not, however, with these that we have at present to do.

At a particular spot on

this iron-bound coast, there is a bold rock or cliff, which the Gaelic

people call “Leac na on,” i.e., the rock of gold. The traveller will

easily find a civil and obliging Bruan man to point out its situation.

The story connected with that rock and its name is one of treachery and

cruelty. For a moment I thought of calling it also a story of love, but

the sequel will show why that word has been omitted. A Caithness

chieftain, probably a Sinclair, though I hope not, seems to have

possessed lands and a residence on this coast. He had wooed and won a

Danish lady or Princess, but we have no record of their courtship, if,

indeed, anything of the kind ever took place. She seems, however, to

have consented to make Caithness her adopted home. At length, the time

of the marriage drew near, and it was decided that the ceremony should

take place on this side the North Sea, Embarking in a Danish vessel, she

sailed for the land of her adoption, and might surely hope for an

affectionate welcome from her lover. She certainly did not come

empty-handed, for the vessel bore the lady’s splendid dowry of gold and

treasure. But alas ! what a fickle, treacherous, cruel creature is man,

though he be a Caitlmessman, or even a Sinclair! The chieftain was more

in love with the dowry than with the lady. Under pretence of securing

her safety, it had been arranged that a bright light should be exhibited

on the coast, toward which the Danes might with confidence steer their

vessel. The greedy, heartless lover fixed that light purposely on the

most dangerous cliff he could select, and the result, unfortunately, was

entirely in accordance with his fell design. At dead of night, when not

a glimmer of light shone in the sky, the bride’s vessel struck the fatal

rock, and in a few brief moments, falling back in shattered fragments,

sunk beneath the waves. The Danish lady and her convoy perished with the

wreck, for not a hand was extended to rescue them. The chieftain roared

with delight at this primary success of his project, but most probably

did not after all gain his ultimate end. In his day it would be no easy

matter, if, indeed, possible at all, to fish up the gold and other

treasure from among the seaweed and rocks. We should all be sorry to

think that the wretch was made one penny the richer by the spoils. Let

us hope that they still lie among the

“Wedges of gold, great

anchors, heaps of pearl,

Inestimable stones, unvalued jewels,

All scattered in the bottom of the sea.”

If even now the Danish

gold and jewellery are there, we shall leave them undisturbed in the

spirit of the poetess who sings—

“Yet more, the depths have

more! what wealth untold,

Far down, and shining through their stillness, lies!

Thou hast the starry gems, the burning gold,

Won from ten thousand royal argosies!

Sweep o’er thy spoils, thou wild and wrathful main!

Earth claims not these again!”

Of the many ruined

castles which stud the cliffs of Caithness, the Sinclairs once possessed

the great majority, for most of them belonged to one branch or other of

that powerful family. Probably one of the oldest of these is the

venerable Castle of Keiss, on the western shore of Sinclair Bay,—a ruin

indeed, yet how stately and firm on its rocky basement. Its main walls

are still wonderfully entire, and its lofty turrets and gables are

visible far over land and sea. On the opposite side of the same spacious

bay, and crowning cliffs of wild grandeur, stand the twin Castles

Sinclair and Girnigoe, the chief stronghold of the Earls of Caithness in

the old days of blood and iron. The very image of that grim and gaunt

fastness recalls the questions and replies of Heine’s song—

“Hast thou seen the castle

olden,

High towering by the sea!

Crimson—bright and golden

The clouds above it be.

Down stooping, it appeareth

In the glassy wave below ;

Its lofty towers it reareth

Where the clouds of even glow.

Well have I seen it towering

That castle by the sea ;

And the moon above it lowering,

And the mists about it flee.

The winds and waves rebounding—

Say, rang they fresh and clear?

Heard’st thou from bright halls sounding

Music and festal cheer.

The winds and waves were sleeping,

But from that castle high

The sound of wailing and weeping

Brought tears into my eye.”

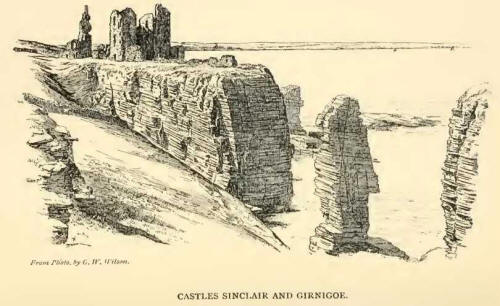

Castles Sinclair and

Girnigoe are perched on a bold, rocky promontory which runs out almost

parallel with the cliffs of the mainland, a deep, wild goe rocking its

surging waters between. Castle Sinclair, the more modern and yet the

more ruinous, stands on the neck of the projecting cape; while Castle

Girnigoe, the older and yet the more perfect, occupies the crown of the

rock, ancl its walls seem at one time to have extended far beyond the

present structure. The twin strongholds may be said to have a joint

tenancy of the peninsula, and once-a-day a drawbridge over a yawning

gulf connected their walls and chambers. Far out upon the point of the

cliffs where they first dip downward toward the sea, are the remains of

an oubliette or secret dungeon. Thence, through a trap door, and by a

steep slide on the face of the rocks, communication might be had with

the waters and boats below.

On the ground floor of

Castle Girnigoe, three or four separate chambers yet remain in a fair

state of preservation. From a comer in one of these, a flight of broken

steps leads down to a damp, vaulted dungeon, dimly lit from a narrow

aperture in the wall. This was the scene of the terrible tragedy, of

which we must presently tell the sad history. If ruins could feel or

manifest the sense of shame, then surely, Girnigoe ! thou mightest well

blush even in thine old age!

“Yet, proudly mid the tide

of years,

Thou lift’st on high thine airy form

Scene of primeval hopes and fears,

Slow yielding to the storm!”

Certainly, if Goethe be

right in describing architecture as petrified music, Castles Sinclair

and Girnigoe sound out one of the most gruesome dirges or laments that

was ever embodied in stone.

About the middle of the

sixteenth century, George Sinclair, Earl of Caithness, became bitterly

incensed against his eldest son, John, the Master of Caithness and his

father’s heir. The cause of disagreement has been variously stated.

According to one account, the Earl had a bitter feud with the

inhabitants of Dornoch in Sutherlandshire, and had sent his son, along

with the chief of the clan Mackay, to punish them. The townspeople had

promised certain concessions, and had given three hostages as a pledge

of their fidelity. The angry, treacherous Earl ordered these men to be

executed forthwith. His son, and Mackay of Strathnaver—to their credit

be it said—refused to carry out his decision, and so the rupture took

place between them and him. The young Master, to escape the anger and

resentment of his father, took refuge with his ally Mackay in the Reay

country, and resided there for several years. This absence from home

gave rise to two other causes of offence and suspicion. In the first

place, rumours from time to time reached the Earl that his son and

Mackay were plotting against him, and even cherished designs against his

life. Moreover, as in many such cases, we must have regard to the

counsel, “ Cherchez la femme; ” and in this instance, it will yield

something. The chief of the Mackays had, it is said, a charming

daughter, who quite captived the Earl’s son, and eventually became his

wife. This gave great offence to his father, who, being by this time a

widower, was himself contemplating matrimony again. He resented the idea

of his son’s outstripping him, and first becoming the father of another

heir to the earldom. Moved by these or such like causes of offence, the

Earl, who was naturally jealous and cruel, laid a plot to ensnare both

his rebellious son and his traditional enemy at once. He invited them to

come to Castle Girnigoe, and professed the most sincere anxiety to be

reconciled to them both.

Trusting to the Earls

good faith, they rode together, on horseback and unattended, to the

fatal towers on Sinclair Bay. As they were entering by the drawbridge,

the Chief of the Mackays noticed what he considered an unusual and

unnecessary force of armed men on duty. Taking alarm at once, he turned

his horse’s head on the very bridge, and fled with all speed. The young

Master was, however, less fortunate. He was at once seized and thrust

down into the damp and gloomy cell in the under regions of Girnigoe; and

there he lay, in cruel neglect and solitude, for many years. His first

keeper was one Murdo Roy, who planned the escape of his young and

gallant prisoner. The plot was discovered by William, the Earl’s second

son, and Murdo was summarily executed for his kindly intentions toward

his ward. His head for some time after adorned the castle walls. A short

time after poor Murdo s fate was thus sealed, William entered the

prisoner’s cell, and the brothers had an angry altercation. At length

John, who was a man of powerful physique, and therefore called Garroiv,

the strong, sprang, fettered though he was, upon his brother, and

actually crushed his life out in an iron embrace. It is but right to add

that William had espoused his father’s side, had threatened his

brother’s life, and would not have been much grieved to have the heir

out of his way.

During these events the

Earl was absent from home, but immediately on his return, lie appointed

two keepers, by name James and Ingram Sinclair, to watch the young

Master, so that he was guarded more carefully and treated more cruelly

than ever. As to the part latterly played by these gaolers, traditions

differ. According to one story, they plundered the castle in the Earl’s

absence, fled with the spoils, and left the Master of Caithness to

perish of famine in his cell. Another version, more circumstantial, and,

alas ! far more revolting, seems unfortunately the true one, or at least

nearer to the sad truth. It is said that the two Sinclairs, instigated

by the Earl himself, deliberately compassed the death of the poor

captive—and that by a most inhuman method. Having starved their victim

for a few days, they then set before him an abundant supply of salt

beef, of which he ate voraciously. Then, when raging thirst came upon

him, they refused him even a drop of water, and left him to die in

writhing agony. The inscription on his tombstone in the old churchyard

of Wick, speaks of him as “ane noble and worthie man, who departed this

life the 15th day of March, 1576.”

The old Earl, the father,

died in Edinburgh in 1583, and was succeeded by George, the son of the

murdered Master. This George very soon took opportunity to avenge his

father’s death upon the brothers Sinclair. One of them, Ingram, was to

be married, and the new Earl, to make his vengeance the more terrible,

chose the wedding day for his purpose. He first met James, who was

making his way to the happy festivities, ran him through with his sword,

and left him a corpse by the roadside. Proceeding yet further on his

bloody errand, he found Ingram with some companions beguiling the time

before the ceremony in a game of football. The Earl approached him at

once, saying, in a tone of cheery innocence, “Do you know, one of my

corbies {i.e., crows, a familiar name for pistols) missed fire this

morning". At the same moment, as if to examine it, he drew a pistol from

the holster on his saddle, and shot the bridegroom dead upon the spot.

Instead of a happy bridal came a double funeral, and no one was bold

enough or strong enough “to bell the cat,” and bring the Earl to

justice. It may even have been thought that he was fully justified in

wreaking vengeance on the men who so cruelly murdered his father. These

were not the days of longspun, wearisome trials. The whole story is but

a specimen of many such deeds and scenes in the old days in Caithness;

let us hope that the one now recorded is the most unnatural and inhuman

of all. If any one thinks that such things never have been done, and

never could be done, south of the Grampians, let him turn to the year

1402, in the kingdom of Fife, and find out what became of the Duke of

Rothesay, the King’s son, in the palace of Falkland. Two blacks do not

make a white; but the question here is, which is the deeper black, and,

really, there seems little to choose between the two cases.

More than perhaps any

other county in Scotland, Caithness has, during the past thirty years

especially, been passing through stage after stage of rapid transition,

almost amounting to revolution. This is true in regard to politics,

social conditions, and religious questions alike.

Public opinion and

sentiment have undergone changes, the pace of which has become more and

more rapid every year. Some of “the adorers of time gone by” have been

weeping and wailing profusely. My own opinion is, that in these changes

there has been much to regret, but far far more to cause rejoicing. It

is not my purpose here to discuss the pros and cons of these various

currents in the minds of men. Two things, however, I think I may do

without offence, namely, state in a few words some of the motive causes

of change and offer a few slight illustrations of the contrast between

the dead or dying past and the living present.

Among the active forces

which have caused upheaval, four seem to me to be the most powerful and

prominent. These are, the spread of education, railway extension, the

wider diffusion of press influence, and the pressure of hard times as

regards the harvests both of land and sea. Only on the first of these

shall I venture to speak ; and though sorely tempted to write chapters,

I must restrain personal feeling and impulse, and be content with a few

sentences. Education was, without doubt, the first of the forces of

change to operate upon Caithness. Fifty years ago, there were many

shrewd and prosperous men in the county, whose training, even in the

three R’s—Reading, Riting, and Rithmetic—was very imperfect indeed. Let

me instance one rather amusing case. It was that of a shoemaker who

provided the Sheriff of the county with boots. The worthy tradesman had

with no little trouble and pains drawn up an account to be presented to

his customer ; yet, when it was completed, lie found, to his chagrin,

that he could not read it himself. Once and again he had made the

attempt and failed; but at length a happy thought gave him immediate

relief and comfort. Turning to a friend, he exclaimed, with a satisfied

smile, “Weel, I canna mak’t oot, but d— cares, it’s gaun til a better

scholar than masel.” What a comfort to know that the Sheriff could read

so well. Such is the story. Even thirty years ago such a case must have

been somewhat rare in the county. At that time the schools of the county

were admirably taught, and the standard of education wonderfully high.

As one evidence for the truth of these statements, I may mention that at

that period, Caithness sent to Edinburgh more students in proportion to

her population than any other county in Scotland, with the possible

exception of Dumfries. There is also one rural parish which may, without

fear of rivalry, claim as natives a larger number of professional men

scattered all over the world than, perhaps, any other in the country.

This general diffusion of sound and well advanced education paved the

way for the breaking up of many an old tradition and sentiment embedded

in the life of the community. Thus has it come to pass that in many

questions affecting especially the Church and the land, “ the axles are

so hot that we have long-been smelling fire.5’ To vary the figure we may

say that what an eminent statesman lately called “ the invisible

creeping wind of public sentiment ” has been blowing about many old

leaves.

In the regions of social

life and of politics, it may be of interest to chronicle some forms or

aspects of change, even though I refrain from pronouncing any opinion

upon them.

Among what are called the

middle classes, the humble and homely ways of half a century ago are

fast passing away. Contentment and simplicity are more rarely found,

while pride and luxury are manifesting themselves in growing measure.

Some one has contrasted these conditions in the following plain and

pithy lines :—

“Man to the plough,

Wife to the sow,

Son to the flail,

Daughter to the pail,

And your rents will be netted ;

But man tally-ho,

Daughter piano,

Son Greek and Latin,

Wife silk and satin,

And you’ll soon be gazetted.”

Very sorry should I be to

apply these words to the middle-class people of Caithness as a whole.

Still, they indicate, in an exaggerated and therefore harmless form, the

direction in which things are tending. Let us hope that in no case will

the sad end with which the lines close be realised. If we look a step

lower in the social scale, what do we find ? Among the small farmers and

crofters the changes in progress have been not so much in social

condition, for that as yet has been little altered, but in political

feeling and aspiration. Twenty or thirty years ago, the minds of these

men were as to great questions in a listless, almost stagnant,

condition.

Within the last decade

the land question has set the heather on fire, and burns on hundreds if

not thousands of hearths in the valleys and villages of Caithness. What

many would call a social rebellion smoulders all over the county, arid

there are not so many now-a-days disposed to echo the pious wish :—

“Bless the squire and his

relations,

And keep us all in our proper stations.”

It is an undoubted

fact—welcome it or bewail it, whichever you please—that Radicalism more

or less extreme is rampant in almost every parish.

Not less real though

perhaps less patent are the changes in relioious thought and customs.

Into these I cannot fully enter, but I may gather as from the surface of

things a few indications of the contrast between the then of fifty years

ago and the now of 1890. Nowhere in all Scotland did there exist at the

earlier period a more dogged and determined conservatism in matters

religious than in Caithness. As to outward forms many would sing, con

amove,

“Old customs! Oh I love

the sound!

However simple they may be;

"Whate’er with time hath sanction found

Is welcome and is dear to me.”

It is the fashion with

some people to stigmatize that spirit in unmeasured terms as if it were

only and wholly evil —the fruit of nothing but tyranny and ignorance.

Those who so speak show on their own part a want of knowledge no less

than of breadth and charity. Among many things which seem to most of us

grotesque and foolish, the candid eye can take note of many things which

were good and noble. It is therefore in no carping or jeering spirit

that I touch upon the lighter side of some phenomena in religious life

which are now little more than memories.

Among the good folks of

Caithness half a century ago the office of the Christian ministry

commanded a singular measure of deference and respect. This was due to

the character both of the office itself and of the men, generally

speaking, who discharged its duties. There were, for example, certain

amusements which might be permissible or barely so among ordinary

Christians, but which were not to be tolerated for a moment in one of “

the cloth.” You remember the cynical charge addressed by Sydney Smith to

a young clergyman :

“Hunt not, fish not, shoot

not,

Dance not, fiddle not, flute not;

Be sure you have nothing to do with the Whigs,

But stay at home and feed your pigs ;

Above all, I make it my particular desire

That at least once a week you dine with the Squire.”

The first six counsels at

all events are in full accordance with the common opinion of religious

people in the far north at that period. Any man who practised such

things would be denounced and boycotted by those who were reputed the

best of the people. Exception, however, was made in favour—if so it can

be called—of the “moderate” ministers. They were considered so

hopelessly wrong in other respects that no one cared to criticise too

nicely any questionable thing they might do.

A curious incident

bearing upon this point occurred in the case of the famous “Apostle of

the North,” Dr John Macdonald of Ferintosh. Some details may have

escaped my memory, but I believe that what follows is in the main

correct. His father, James Macdonald, was catechist in the parish of

Reay, and was a man of high religious repute. His son John was born in

the depth of winter, and the father carried his child through wreaths of

snow to the manse that he might be baptized. The minister was from home

; he had gone out shooting with the laird; but the catechist, nothing

daunted and bearing his tender load, went in pursuit over the snowy

moors, and at length, after no little labour, came up with his pastor.

The ceremony was performed there and then, simply and briefly. Stepping

out upon a frozen sheet of water, the minister broke a hole in the ice,

lifted the all but frozen element between his fingers, and dropped it on

the child’s face with the usual formula. That boy became the wonderful

preacher of after years, and often with pawky humour declared that his

baptism was but a foretaste of the cold treatment he ever after received

at the hands of the “ Moderates.5’ No evangelical who cared for his good

name and influence would £0 shooting with the laird, and have to be

hunted in such a fashion.

Since godly ministers

were held in such high estimation, curious results sometimes followed.

Young preachers were tempted to imitate the old; and, as usual, what

they reproduced was often the very faults or foibles of the model. The

most remarkable thing is that at times a young man was highly thought of

because there was some resemblance in his person or manner to a very

weakness or oddity of a greater than himself. A highly respected

minister in Caithness, about the year 1830, was the Rev. Archibald Cook

of Bruan, who was commonly spoken of as Archie Cook. He was a man of

deep piety and quaint genius, but was also peculiar and somewhat

eccentric. In his day, a young man, newly fledged, preached in a

Caithness Church. After service, there were many comments on his

performance—mostly of an unfavourable kind. One good old woman, however,

abounding in Christian charity, found out one peculiar excellence at

least in the neophyte. Being asked by a neighbour what she thought of

him, she at once replied,

“Oh, wumman/am thinkan

lie’s a rayal godly, gracious young man. He coughs jist like Airchie

Cook.”

I have even been assured

that the qualification mentioned was the means of his appointment as

pastor over that very congregation. It may not be wise to show any

countenance to such a view, for it might produce effects at which one

shudders among the rising ministry. We do not wish to find in the pulpit

analogies of infinite variety to the Alexandra limp or Archie Cook’s

cough.

If in these old days the

ministers were carefully fenced in by restraints in one direction, so

were the people by laws and statutes in others. Here, however, I must

confess that I go back more than two hundred years for my illustration.

It appears that, even at that early period, the offence of

non-church-going was sadly prevalent. If so, it was not for lack of

strong enactments on the subject. Here is an extract from the Session

Records of the parish of Canisbay :—

“December 27,

1652.—Ordained yt (y for th, or the, all through) for mending ye people,

ye better to keepe ye Kirk, a roll of ye names of ye families be taken

up, and Sabbathlie, yt they be called upon by name, and who bees notted

absent sail pay 40d. toties quoties.” The last two words simply mean

that “as often,” as the offence was committed, “so often” should the

penalty be inflicted. The worthy minister who first quoted this extract

fifty years ago, touchingly remarks, “ This is a most salutary

regulation.” I believe that, even down to his day, the law might have

been enforced; who would dare to attempt it now? But mark, I pray you,

what a wistful, plaintive ring there is about the minister’s

declaration. Can the 40d. have anything to do with it? How the stipends

and spirits of ministers would mount up, and the coffers of the Churches

bulge out, if such a source of revenue could be tapped in this wealthy

but degenerate nineteenth century! No wonder many good people in this

world are adorers of the past! Must I add a line more? No wonder that

many more profanely prefer the present!

An old custom, not yet

extinct, but fast losing its hold, was the “reading of the line” in the

public service of praise. As some may not understand that expression, it

may be well to state its meaning. When the minister “gave out ” several

verses of a Psalm to be sung, the precentor proceeded to read aloud the

first line with strong intonation, and then led the congregation in

singing it. He then read the second line in the same fashion, and again

led off the volume of united praise; and so on with each line of the

verses announced from the pulpit. The practice probably originated in

the fact that many worshippers in the Highlands were unable to read

either their own or any other language. In that ease, it served the

useful purpose of enabling all to join in the praises of the sanctuary.

Through those congregations in which the services were conducted in

Gaelic, the “reading of the line” became common in Caithness, even in

those parishes where the English language was the medium of worship. No

stranger can have any idea of the importance attached to this custom in

the north. It has been adhered to with the utmost tenacity, and dies

hard. When attempts have been made in certain parts of the country to

secure its abandonment, bitter wrangling and sometimes even serious

disruption in congregations have been the consequence. The “reading of

the line” has even been accounted an essential in spiritual worship, and

any word or action tending to its disparagement has been regarded as

nothing less than sacrilege. Some who can see nothing either specially

good or specially evil in the practice may be disposed to ask on what

grounds its sacred character has been supposed to rest. That question I

cannot fully answer, but this I do know, that it has sometimes been

defended on grounds of Scripture. The words in the prophecy of Isaiah,

“line upon line, line upon line” have been quoted as an argument and

warrant for the practice. It is not likely that the custom will long

survive unless provided with some better defence.

The false interpretation

put upon the prophet’s words is no better and no worse than another of

which I have heard. A very different application of the passage was once

made not many miles from Grangemouth in Stirlingshire. Two brothers

called Little—please note the name—possessed a small property in that

district. They were bachelors, and, perhaps, a little lonely, so upon

one occasion they invited both the parish minister and the parish

schoolmaster to dinner. The brothers occupied opposite ends of the

table, while the two guests sat vis-a-vis at the sides. During dinner,

or more probably towards its close, the elder brother took up the

prophet’s words, and applied them skilfully to the group around the

table. Extending his left hand toward the schoolmaster, he said, “Line

upon line;” reaching out his right toward the minister, he said,

“precept upon precept;” touching his own breast, he said, “here a

Little;” pointing across to his brother, he said, “and there a LittleIn

Caithness the reading of the line” is to a large extent a thing of the

past. Improved education and taste are both against it, and its days are

numbered.

Before closing this

chapter, it may be noted that among the old ministers and people of

Caithness, quiet humour was both displayed and appreciated. Moreover, it

was not considered out of place in its moderate application even to

sacred things. There is, I know, one clergyman still alive and much

respected in Caithness, who could supply many choice illustrations of

the truth of what I have said. Many have long wished he would give them

to the public. Those who like myself are natives of the county, but have

lived very little in it, must be content with small store of these sweet

morsels. Let me offer one or two out of the small stock I possess.

It has always been a

marked characteristic of the religious people of Caithness, that they

made large use of Scripture language and illustration even in the

affairs of everyday life. This arose from no irreverence, but from the

strong hold which the sacred diction had taken of their minds. Their

speech was saturated with the words and phrases of Holy "Writ. On one

occasion two or three of “ the Men ” came to visit my father at the

manse. It may be well to mention for the information of some readers,

that these pious laymen of religious repute and influence were called “

Men,” as some one has said, “ not because they were not women, but

because they were not ministers.” They were elders of the Church and

leaders of the people in spiritual matters. W ell, a few of them came

from a considerable distance, and knocked at the kitchen door of the

manse. The servant invited them to enter, provided them with seats, and

asked what message she would carry to her master. One of them, speaking

for all, gave this peculiar reply. “Tell ’im ’e be keepan’ ’is picklies

o’ whate because 5e Midianites hev come.” When the girl delivered her

message, my father’s smile told that he understood its meaning perfectly

and at once, and he went downstairs immediately to give his visitors a

cordial welcome. Perhaps I should repeat the words in a form

intelligible to all. “Tell him to be keeping his pickles of wheat

because the Midianites have come.” Now, what did the message mean? In

the book of Judges we read that Gideon “threshed wheat by the wine

press, to hide it from the Midianites.” So the worthy men, clothing

their words in Scripture language, intended to say, “If the minister has

any precious truths or experiences which he does not care to communicate

to others, let him hide them, for we are like the Midianites—we shall

steal them if we can.” There is something far more than merely delicate

humour in the story.

On one occasion a most

worthy minister in the parish of Latheron offered to drive me as far as

the Ord, the boundary headland of Caithness, on my way southward to

Ross-shire. As we were passing Dunbeath, we overtook a somewhat

doubtful-looking character, who asked if he might get a “lift,” and

assured us he would trespass on our kindness only for “a mile and no

more.”

“Come away, then,” said

Mr M., the minister, in a kindly tone; “get up behind.”

On we went at a fair

pace, and the mile was soon covered. Our new acquaintance kept up a

lively conversation with the minister, whom he had at once recognised.

By-and-bye the second mile was more than past, and he still kept his

seat. At last Mr M. thought it high time to give the stranger a hint,

and he did it with no less delicacy than humour.

“Do you know, friend,”

said the minister, “you have reminded me very forcibly of one of the

injunctions given by our Lord to His disciples?”

“Indeed—indeed!—what was

that?” replied the stranger, much interested, and apparently gratified.

“Well,” said Mr M.,

turning half round, “don’t you remember the words, ‘ Whosoever shall

compel thee to go a mile, go with him twain?”

The stranger was silent

for a little while, and then, evidently desiring to ponder the words

alone, bade us a grateful “Good-bye" and stepped down from his seat.

The following are two

illustrations from the sayings of eminent preachers belonging to

Caithness. On a certain occasion one of these announced as his text the

words in Revelation, “There was silence in heaven for the space of

half-an-hour.” He began his discourse by declaring, with much emphasis,

“Well, friends, this is a sad intimation for the female portion of my

congregation.” It strikes me I have heard the same remark attributed to

some southern divine. Perhaps I am wrong; I shall be glad if my memory

fails me in this particular. If two, or even more, have said it, may it

not be because great minds often arrive without any collusion at the

same important conclusion?

Another Caithness

minister was once discoursing on the duty of Christians to “wash one

another’s feet.” Here is a quaint extract from the sermon—taken down

however, before the days of shorthand.

“One way in which

disciples wash one another’s feet is by reproving one another. But the

reproof must not be couched in angry words, so as to destroy the effect;

nor in tame, so as to fail of effect. It must be just as in washing a

brother’s feet—you must not use boiling water to scald, nor frozen water

to freeze them.”

Some of the ministers of

Caithness in these old days were narrow in opinion, severe in censure,

arbitrary in rule, and harsh in doctrine; but most of them were also men

of genuine piety, much kindliness of heart, and warm hospitality; a few

at least bore the stamp of lofty genius. They “served their

generation”—they were not sent or meant to serve ours ; and as a body

they deserved the high respect in which they were held by the people. |