ANY sunny afternoon, on

Fifth Avenue, or at night in the table d'hote restaurants of University

Place, you may meet the soldier of fortune who of all his brothers in

arms now living is the most remarkable. You may have noticed him; a

stiffly erect, distinguished-looking man, with gray hair, an imperial of

the fashion of Louis Napoleon, fierce blue eyes, and across his forehead

a sabre cut.

This is Henry Ronald Douglas Maclver, for some time in India an ensign

in the Sepoy mutiny; in Italy, lieutenant under Garibaldi; in Spain,

captain under Don Carlos; in our Civil War, major in the Confederate

army; in Mexico, lieutenant-colonel under the Emperor Maximilian;

colonel under Napoleon III, inspector of cavalry for the Khedive of

Egypt, and chief of cavalry and general of brigade of the army of King

Milan of Servia. These are only a few of his military titles. In 1884

was published a book giving the story of his life up to that year. It

was called “Under Fourteen Flags.” If to-day General MacIver were to

reprint the book, it would be called “Under Eighteen Flags.”

Maclver was born on Christmas Day, 1841, at sea, a league off the shore

of Virginia. His mother was Miss Anna Douglas of that State; Ronald

Maclver, his father, was a Scot, a Ross-shire gentleman, a younger son

of the chief of the Clan Maclver. Until he was ten years old young

Maclver played in Virginia at the home of his father. Then, in order

that he might be educated, he was shipped to Edinburgh to an uncle,

General Donald Graham. After five years his uncle obtained for him a

commission as ensign in the Honourable East India Company, and at

sixteen, when other boys are preparing for college, Maclver was in the

Indian Mutiny, fighting, not for a flag, nor a country, but as one

fights a wild animal, for his life. He was wounded in the arm, and, with

a sword, cut over the head. As a safeguard against the sun the boy had

placed inside his helmet a wet towel. This saved him to fight another

day, but even with that protection the sword sank through the helmet,

the towel, and into the skull. Today you can see the scar. He was left

in the road for dead, and even after his wounds had healed, was six

weeks in the hospital.

This rough handling at the very start might have satisfied some men, but

in the very next war Maclver was a volunteer and wore the red shirt of

Garibaldi. He remained at the front throughout that campaign, and until

within a few years there has been no campaign of consequence in which he

has not taken part. He served in the Ten Years’ War in Cuba, in Brazil,

in Argentina, in Crete, in Greece, twice in Spain in Carlist

revolutions, in Bosnia, and for four years in our Civil War under

Generals Jackson and Stuart around Richmond. In this great war he was

four times wounded.

It was after the surrender of the Confederate Army, that, with other

Southern officers, he served under Maximilian in Mexico; in Egypt, and

in France. Whenever in any part of the world there was fighting, or the

rumor of fighting, the procedure of the general invariably was the same.

He would order himself to instantly depart for the front, and on

arriving there would offer to organize a foreign legion. The command of

this organization always was given to him. But the foreign legion was

merely the entering wedge. He would soon show that he was fitted for a

better command than a band of undisciplined volunteers, and would

receive a commission in the regular army. In almost every command in

which he served that is the manner in which promotion came. Sometimes he

saw but little fighting, sometimes he should have died several deaths,

each of a nature more unpleasant than the others. For in war the obvious

danger of a bullet is but a three hundred to one shot, while in the pack

against the combatant the jokers are innumerable. And in the career of

the general the unforeseen adventures are the most interesting. A man

who in eighteen campaigns has played his part would seem to have earned

exemption from any other risks, but often it was outside the

battle-field that Maclver encountered the greatest danger. He fought

several duels, in two of which he killed his adversary; several attempts

were made to assassinate him, and while on his way to Mexico he was

captured by hostile Indians. On returning from an expedition in Cuba he

was cast adrift in an open boat and for days was without food.

Long before I met General Maclver I had read his book and had heard of

him from many men who had met him in many different lands while engaged

in as many different undertakings. Several of the older war

correspondents knew him intimately; Bennett Burleigh of the Telegraph

was his friend, and E. F. Knight of the Times was one of those who

volunteered for a filibustering expedition which Maclver organized

against New Guinea. The late Colonel Ochiltree of Texas told me tales of

Maclver’s bravery, when as young men they were fellow officers in the

Southern Army, and Stephen Bonsai had met him when Maclver was United

States Consul at Denia in Spain. When Maclver arrived at this post, the

ex-consul refused to vacate the Consulate, and Maclver wished to settle

the difficulty with duelling pistols. As Denia is a small place, the

inhabitants feared for their safety, and Bonsai, who was our charge

d’affaires then, was sent from Madrid to adjust matters. Without

bloodshed he got rid of the ex-consul, and later Maclver so endeared

himself to the Denians that they begged the State Department to retain

him in that place for the remainder of his life.

Before General Maclver was appointed to a high position at the St. Louis

Fair, I saw much of him in New York. His room was in a side street in an

old-fashioned boardinghouse, and overlooked his neighbors’ backyard and

a typical New York City sumac tree; but when the general talked one

forgot he was within a block of the Elevated, and roamed over all the

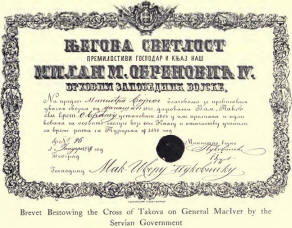

world. On his bed he would spread out wonderful parchments, with

strange, heathenish inscriptions, with great seals, with faded ribbons.

These were signed by Sultans, Secretaries of War, Emperors, filibusters.

They were military commissions, titles of nobility, brevets for

decorations, instructions and commands from superior officers.

Translated the phrases ran: “Imposing special confidence in,” “we

appoint,” or “create,” or “declare,” or “In recognition of services

rendered to our person,” or “country,” or “cause,” or “For bravery on

the field of battle we bestow the Cross”.

As must a soldier, the general travels “ light,” and all his worldly

possessions were crowded ready for mobilization into a small compass. He

had his sword, his field blanket, his trunk, and the tin despatch boxes

that held his papers. From these, like a conjurer, he would draw

souvenirs of all the world. From the embrace of faded letters, he would

unfold old photographs, daguerreotypes, and miniatures of fair women and

adventurous men: women who now are queens in exile, men who, lifted on

waves of absinthe, still, across a cafe table, tell how they will win

back a crown.

Once in a written

document the general did me the honor to appoint me his literary

executor, but as he is young, and as healthy as myself, it never may be

my lot to perform such an unwelcome duty. And to-day all one can write

of him is what the world can read in “Under Fourteen Flags,” and some of

the “foot-notes to history” which I have copied from his scrap-book.

This scrap-book is a wonderful volume, but owing to “political” and

other reasons, for the present, of the many clippings from newspapers it

contains there are only a few I am at liberty to print. And from them it

is difficult to make a choice. To sketch in a few thousand words a

career that had developed under Eighteen Flags is in its very wealth

embarrassing.

Here is one story, as told by the scrap-book, of an expedition that

failed. That it failed was due to a British Cabinet Minister; for had

Lord Derby possessed the imagination of the Soldier of Fortune, his

Majesty’s dominions might now be the richer by many thousands of square

miles and many thousands of black subjects.

On October 29, 1883, the following appeared in the London Standard: “The

New Guinea Exploration and Colonization Company is already chartered,

and the first expedition expects to leave before Christmas.” “The

prospectus states settlers intending to join the first party must

contribute one hundred pounds toward the company. This subs scription

will include all expenses for passage money. Six months’ provisions will

be provided, together with tents and arms for protection. Each

subscriber of one hundred pounds is to obtain a certificate entitling

him to one thousand acres.”

The view of the colonization scheme taken by the Times of London, of the

same date, is less complaisant. “The latest commercial sensation is a

proposed company for the seizure of New Guinea. Certain adventurous

gentlemen are looking out for one hundred others who have money and a

taste for buccaneering. When the company has been completed, its

shareholders are to place themselves under military regulations, sail in

a body for New Guinea, and without asking anybody’s leave, seize upon

the island and at once, in some unspecified way, proceed to realize

large profits. If the idea does not suggest comparisons with the large

designs of Sir Francis Drake, it is at least not unworthy of Captain

Kidd.”

When we remember the manner in which some of the colonies of Great

Britain were acquired, the Times seems almost squeamish.

In a Melbourne paper, June, 1884, is the following paragraph:

“Toward the latter part of 1883 the Government of Queensland planted the

flag of Great Britain on the shores of New Guinea. When the news reached

England it created a sensation. The Earl of Derby, Secretary for the

Colonies, refused, however, to sanction the annexation of New Guinea,

and in so doing acted contrary to the sincere wish of every

right-thinking Anglo-Saxon under the Southern Cross.

“While the subsequent correspondence between the Home and Queensland

governments was going on, Brigadier-General H. R. Maclver originated and

organized the New Guinea Exploration and Colonization Company, in

London, with a view to establishing settlements on the island. The

company, presided over by General Beresford of the British Army, and

having an eminently representative and influential board of directors,

had a capital of two hundred and fifty thousand pounds, and placed the

supreme command of the expedition in the hands of General Maclver.

Notwithstanding the character of the gentlemen composing the board of

directors, and the truly peaceful nature of the expedition, his Lordship

informed General Maclver that in the event of the latter’s attempting to

land on New Guinea, instructions would be sent to the officer in command

of her Majesty’s fleet in the Western Pacific to fire upon the company’s

vessel. This meant that the expedition would be dealt with as a

filibustering one.”

In Judy, September 21, 1887, appears:

“We all recollect the treatment received by Brigadier-General Macl. in

the action he took with respect to the annexation of New Guinea. The

General, who is a sort of Pizarro, with a dash of D’Artagnan, was

treated in a most scurvy manner by Lord Derby. Had Maclver not been

thwarted in his enterprise, the whole of New Guinea would now have been

under the British flag, and we should not be cheek-by-jowl with the

Germans, as we are in too many places.”

Society, September 3, 1887, says:

“The New Guinea expedition proved abortive, owing to the blundering

shortsightedness of the then Government, for which Lord Derby was

chiefly responsible, but what little foothold we possess in New Guinea

is certainly due to General Maclver’s gallant effort.”

Copy of statement made by J. Rintoul Mitchell, June 2, 1887:

“About the latter end of the year 1883, when I was editor-in-chief of

the Englishman in Calcutta, I was told by Captain de Deaux, assistant

secretary in the Foreign Office of the Indian Government, that he had

received a telegram from Lord Derby to the effect that if General

Maclver ventured to land upon the coast of New Guinea it would become

the duty of Lord Ripon, Viceroy, to use the naval forces at his command

for the purpose of deporting General Macl. Sir Aucland Calvin can

certify to this, as it was discussed in the Viceregal Council.”

Just after our Civil War Maclver was interested in another expedition

which also failed. Its members called themselves the Knights of Arabia,

and their object was to colonize an island much nearer to our shores

than New Guinea. Maclver, saying that his oath prevented, would never

tell me which island this was, but the reader can choose from among

Cuba, Haiti, and the Hawaiian group. To have taken Cuba, the

“colonizers” would have had to fight not only Spain, but the Cubans

themselves, on whose side they were soon fighting in the Ten Years’ War;

so Cuba may be eliminated. And as the expedition was to sail from the

Atlantic side, and not from San Francisco, the island would appear to be

the Black Republic. From the records of the times it would seem that the

greater number of the Knights of Arabia were veterans of the Confederate

Army, and there is no question but that they intended to subjugate the

blacks of Haiti and form a republic for white men, in which slavery

would be recognized. As one of the leaders of this filibustering

expedition, Maclver was arrested by General Phil Sheridan and for a

short time cast into jail. This chafed the General’s spirit, but he

argued philosophically that imprisonment for filibustering, while

irksome, brought with it no reproach. And, indeed, sometimes the only

difference between a filibuster and a government lies in the fact that

the government fights the gunboats of only the enemy while a filibuster

must dodge the boats of the enemy and those of his own countrymen. When

the United States went to war with Spain there were many men in jail as

filibusters, for doing that which at the time the country secretly

approved, and later imitated. And because they attempted exactly the

same thing for which Dr. Jameson was imprisoned in Holloway Jail, two

hundred thousand of his countrymen are now wearing medals.

The by-laws of the Knights of Arabia leave but little doubt as to its

object.

By-law No. II reads:

“We, as Knights of Arabia, pledge ourselves to aid, comfort, and protect

all Knights of Arabia, especially those who are wounded in obtaining our

grand object.

“III—Great care must be taken that no unbeliever or outsider shall gain

any insight into the mysteries or secrets of the Order.

“IV—The candidate will have to pay one hundred dollars cash to the

Captain of the Company, and the candidate will receive from the

Secretary a Knight of Arabia bond for one hundred dollars in gold, with

ten per cent interest, payable ninety days after the recognition of (The

Republic of) by the United States, or any government.

“V—All Knights of Arabia will be entitled to one hundred acres of land,

location of said land to be drawn for by lottery. The products are

coffee, sugar, tobacco, and cotton.”

A local correspondent of the New York Herald writes of the arrest of

Maclver as follows:

“When Maclver will be tried is at present unknown, as his case has

assumed a complicated aspect. He claims British protection as a subject

of her British Majesty, and the English Consul has forwarded a statement

of his case to Sir Frederick Bruce at Washington, accompanied by a copy

of the by-laws. General Sheridan also has forwarded a statement to the

Secretary of War, accompanied not only by the bylaws, but very important

documents, including letters from Jefferson Davis, Benjamin, the

Secretary of State of the Confederate States, and other personages

prominent in the Rebellion, showing that Maclver enjoyed the highest

confidence of the Confederacy.”

As to the last statement, an open letter I found in his scrap-book is an

excellent proof. It is as follows:

“To officers and members of all camps of United Confederate Veterans: It

affords me the greatest pleasure to say that the bearer of this letter,

General Henry Ronald Maclver, was an officer of great gallantry in the

Confederate Army, serving on the staff at various times of General

Stonewall Jackson, J. E. B. Stuart, and E. Kirby Smith, and that his

official record is one of which any man may be proud.

“Respectfully, Marcus J. Wright,

Agent for the Collection of Confederate Records.

“War Records Office, War Department, Washington, July 8, 1895.”

At the close of the war duels between officers of the two armies were

not infrequent. In the scrap-book there is the account of one of these

affairs sent from Vicksburg to a Northern paper by a correspondent who

was an eyewitness of the event. It tells how Major Maclver, accompanied

by Major Gillespie, met, just outside of Vicksburg, Captain Tomlin of

Vermont, of the United States Artillery Volunteers. The duel was with

swords. Maclver ran Tomlin through the body. The correspondent writes:

“The Confederate officer wiped his sword on his handkerchief. In a few

seconds Captain Tomlin expired. One of Major Maclver’s seconds called to

him: * He is dead; you must go. These gentlemen will look after the body

of their friend/ A negro boy brought up the horses, but before mounting

Mac-Iver said to Captain Tomlin’s seconds: ‘ My friends are in haste for

me to go. Is there anything I can do? I hope you consider that this

matter has been settled honorably?"

“There being no reply, the Confederates rode away.”

In a newspaper of to-day so matter-of-fact an acceptance of an event so

tragic would make strange reading.

From the South Maclver crossed through Texas to join the Royalist army

under the Emperor Maximilian. It was while making his way, with other

Confederate officers, from Galveston to El Paso, that Maclver was

captured by the Indians. He was not ill-treated by them, but for three

months was a prisoner, until one night, the Indians having camped near

the Rio Grande, he escaped into Mexico. There he offered his sword to

the Royalist commander, General Mejia, who placed him on his staff, and

showed him some few skirmishes. At Monterey Maclver saw big fighting,

and for his share in it received the title of Count, and the order of

Guadaloupe. In June, contrary to all rules of civilized war, Maximilian

was executed and the empire was at an end. Maclver escaped to the coast,

and from Tampico took a sailing vessel to Rio de Janeiro. Two months

later he was wearing the uniform of another emperor, Dom Pedro, and,

with the rank of lieutenant-colo-nel, was in command of the Foreign

Legion of the armies of Brazil and Argentina, which at that time as

allies were fighting against Paraguay.

Maclver soon recruited seven hundred men, but only half of these ever

reached the front. In Buenos Ayres cholera broke out and thirty thousand

people died, among the number about half the Legion. Maclver was among

those who suffered, and before he recovered was six weeks in hospital.

During that period, under a junior officer, the Foreign Legion was sent

to the front, where it was disbanded.

On his return to Glasgow, Maclver foregathered with an old friend,

Bennett Burleigh, whom he had known when Burleigh was a lieutenant in

the navy of the Confederate States. Although to-day known as a

distinguished war correspondent, in those days Burleigh was something of

a soldier of fortune himself, and was organizing an expedition to assist

the Cretan insurgents against the Turks. Between the two men it was

arranged that Maclver should precede the expedition to Crete and prepare

for its arrival. The Cretans received him gladly, and from the

provisional government he received a commission in which he was given “

full power to make war on land and sea against the enemies of Crete, and

particularly against the Sultan of Turkey and the Turkish forces, and to

burn, destroy, or capture any vessel bearing the Turkish flag.”

This permission to destroy the Turkish navy single-handed strikes one as

more than generous, for the Cretans had no navy, and before one could

begin the destruction of a Turkish gunboat it was first necessary to

catch it and tie it to a wharf.

At the close of the Cretan insurrection Maclver crossed to Athens and

served against the brigands in Kisissia on the borders of Albania and

Thessaly as volunteer aide to Colonel Corroneus, who had been

commander-in-chief of the Cretans against the Turks. Maclver spent three

months potting at brigands, and for his services in the mountains was

recommended for the highest Greek decoration.

From Greece it was only a step to New York, and almost immediately

Maclver appears as one of the Goicouria-Christo expedition to Cuba, of

which Goicouria was commander-in-chief, and two famous American

officers, Brigadier-General Samuel C. Williams was a general and Colonel

Wright Schumburg was chief of staff.

In the scrap-book I find “General Order No. II of the Liberal Army of

the Republic of Cuba, issued at Cedar Keys, October 3, 1869.” In it

Colonel Maclver is spoken of as in charge of officers not attached to

any organized corps of the division. And again:

“General Order No. V, Expeditionary Division, Republic of Cuba, on board

Lilian ” announces that the place to which the expedition is bound has

been changed, and that General Wright Schumburg, who now is in command,

orders “ all officers not otherwise commissioned to join Colonel

Maclver’s ‘ Corps of Officers.”

The Lilian ran out of coal, and to obtain firewood put in at Cedar Keys.

For two weeks the patriots cut wood and drilled upon the beach, when

they were captured by a British gunboat and taken to Nassau. There they

were set at liberty, but.their arms, boat, and stores were confiscated.

In a sailing vessel Maclver finally reached Cuba, and under Goicouria,

who had made a successful landing, saw some “ help yourself ” fighting.

Goicouria’s force was finally scattered, and Maclver escaped from the

Spanish soldiery only by putting to sea in an open boat, in which he

endeavored to make Jamaica.

On the third day out he was picked up by a steamer and again landed at

Nassau, from which place he returned to New York.

At that time in this city there was a very interesting man named

Thaddeus P. Mott, who had been an officer in our army and later had

entered the service of Ismail Pasha. By the Khedive he had been

appointed a general of division and had received permission to

reorganize the Egyptian army.

His object in coming to New York was to engage officers for that

service. He came at an opportune moment. At that time the city was

filled with men who, in the Rebellion, on one side or the other, had

held command, and many of these, unfitted by four years of soldiering

for any other calling, readily accepted the commissions which Mott had

authority to offer. New York was not large enough to keep Maclver and

Mott long apart, and they soon came to an understanding. The agreement

drawn up between them is a curious document. It is written in a neat

hand on sheets of foolscap tied together like a Com-mencement-day

address, with blue ribbon. In it Maclver agrees to serve as colonel of

cavalry in the service of the Khedive. With a few legal phrases omitted,

the document reads as follows:

“Agreement entered into this 24th day of March, 1870, between the

Government of his Royal Highness the Khedive of Egypt, represented by

General Thad-deus P. Mott of the first part, and H. R. H. Maclver of New

York City.

“The party of the second part, being desirous of entering into the

service of party of the first part, in the military capacity of a

colonel of cavalry, promises to serve and obey party of the first part

faithfully and truly in his military capacity during the space of five

years from this date; that the party of the second part waives all

claims of protection usually afforded to Americans by consular and

diplomatic agents of the United States, and expressly obligates himself

to be subject to the orders of the party of the first part, and to make,

wage, and vigorously prosecute war against any and all the enemies of

party of the first part; that the party of the second part will not

under any event be governed, controlled by, or submit to, any order,

law, mandate, or proclamation issued by the Government of the United

States of America, forbidding party of the second part to serve party of

the first part to make war according to any of the provisions herein

contained, it being, however, distinctly understood that nothing herein

contained shall be construed as obligating party of the second part to

bear arms or wage war against the United States of America.

“Party of the first part promises to furnish party of the second part

with horses, rations, and pay him for his services the same salary now

paid to colonels of cavalry in United States army, and will furnish him

quarters suitable to his rank in army. Also promises, in the case of

illness caused by climate, that said party may resign his office and

shall receive his expenses to America and two months’ pay; that he

receives one-fifth of his regular pay during his active service,

together with all expenses of every nature attending such enterprise.”

It also stipulates as to what sums shall be paid his family or children

in case of his death.

To this Maclver signs this oath:

“In the presence of the ever-living God, I swear that I will in all

things honestly, faithfully, and truly keep, observe, and perform the

obligations and promises above enumerated, and endeavor to conform to

the wishes and desires of the Government of his Royal Highness the

Khedive of Egypt, in all things connected with the furtherance of his

prosperity, and the maintenance of his throne.”

On arriving at Cairo, Maclver was appointed inspector-general of

cavalry, and furnished with a uniform, of which this is a description:

“It consisted of a blue tunic with gold spangles, embroidered in gold up

the sleeves and front, neat-fitting red trousers, and high

patent-leather boots, while the inevitable fez completed the gay

costume.”

The climate of Cairo did not agree with Maclver, and, in spite of his

“gay costume,” after six months he left the Egyptian service. His

honorable discharge was signed by Stone Bey, who, in the favor of the

Khedive, had supplanted General Mott.

It is a curious fact that, in spite of his ill health, immediately after

leaving Cairo, Maclver was sufficiently recovered to at once plunge into

the Franco-Prussian War. At the battle of Orleans, while on the staff of

General Chanzy, he was wounded. In this war his rank was that of a

colonel of cavalry of the auxiliary army.

His next venture was in the Carlist uprising of 1873, when he formed a

Carlist League, and on several occasions acted as bearer of important

messages from the “King,” as Don Carlos was called, to the sympathizers

with his cause in France and England.

Maclver was promised, if he carried out successfully a certain mission

upon which he was sent, and if Don Carlos became king, that he would be

made a marquis. As Don Carlos is still a pretender, Maclver is still a

general.

Although in disposing of his sword Maclver never allowed his personal

predilections to weigh with him, he always treated himself to a hearty

dislike of the Turks, and we next find him fighting against them in

Herzegovina with the Montenegrins. And when the Servians declared war

against the same people, Maclver returned to London to organize a

cavalry brigade to fight with the Servian army.

Of this brigade and of the rapid rise of Maclver to highest rank and

honors in Servia, the scrap-book is most eloquent. The cavalry brigade

was to be called the Knights of the Red Cross.

In a letter to the editor of the Hour, the general himself speaks of it

in the following terms:

“It may be interesting to many of your readers to learn that a select

corps of gentlemen is at present in course of organization under the

above title with the mission of proceeding to the Levant to take

measures in case of emergency for the defense of the Christian

population, and more especially of British subjects who are to a great

extent unprovided with adequate means of protection from the religious

furies of the Mussulmans. The lives of Christian women and children are

in hourly peril from fanatical hordes. The Knights will be carefully

chosen and kept within strict military control, and will be under

command of a practical soldier with large experience of the Eastern

countries. Templars and all other Crusaders are invited to give aid and

sympathy.”

Apparently Maclver was not successful in enlisting many Knights, for a

war correspondent at the capital of Servia, waiting for the war to

begin, writes as follows:

“A Scotch soldier of fortune, Henry Maclver, a colonel by rank, has

arrived at Belgrade with a small contingent of military adventurers.

Five weeks ago I met him in Fleet Street, London, and had some talk

about his ‘expedition.' He had received a commission from the Prince of

Servia to organize and command an independent cavalry brigade, and he

then was busily enrolling his volunteers into a body styled ‘ The

Knights of the Red Cross/ I am afraid some of his bold Crusaders have

earned more distinction for their attacks on Fleet Street bars than they

are likely to earn on Servian battlefields, but then I must not

anticipate history.”

Another paper tells that at the end of the first week of his service as

a Servian officer, Maclver had enlisted ninety men, but that they were

scattered about the town, many without shelter and rations:

“He assembled his men on the Rialto, and in spite of official

expostulation, the men were marched up to the Minister’s four

abreast—and they marched fairly well, making a good show. The War

Minister was taken by storm, and at once granted everything. It has

raised the English colonel’s popularity with his men to fever heat.”

This from the Times,

London:

“Our Belgrade correspondent telegraphs last night:

“‘There is here at present a gentleman named Maclver. He came from

England to offer himself and his sword to the Servians. The Servian

Minister of War gave him a colonel’s commission. This morning I saw him

drilling about one hundred and fifty remarkably fine-looking fellows,

all clad in a good serviceable cavalry uniform, and he has horses.'”

Later we find that:

“Colonel Maclver’s Legion of Cavalry, organizing here, now numbers over

two hundred men.”

And again:

“Prince Nica, a Roumanian cousin of the Princess Natalie of Servia, has

joined Colonel Maclver’s cavalry corps.”

Later, in the Court Journal, October 28, 1876, we read:

“Colonel Maclver, who a few years ago was very well known in military

circles in Dublin, now is making his mark with the Servian Army. In the

war against the Turks, he commands about one thousand Russo-Servian

cavalry.”

He was next to receive the following honors:

“Colonel Maclver has been appointed commander of the cavalry of the

Servian Armies on the Morava and Timok, and has received the Cross of

the Takovo Order from General Tchernaieff for gallant conduct in the

field, and the gold medal for valor.”

Later we learn from the Daily News:

“Mr. Lewis Farley, Secretary of the ‘League in Aid of Christians of

Turkey/ has received the following letter, dated Belgrade, October 10,

1876:

“‘Dear Sir : In reference to the embroidered banner so kindly worked by

an English lady and forwarded by the League to Colonel Maclver, I have

great pleasure in conveying to you the following particulars. On Sunday

morning, the Flag having been previously consecrated by the Archbishop,

was conducted by a guard of honor to the palace, and Colonel Maclver, in

the presence of Prince Milan and a numerous suite, in the name and on

behalf of yourself and the fair donor, delivered it into the hands of

the Princess Natalie. The gallant Colonel wore upon this occasion his

full uniform as brigade commander and Chief of Cavalry of the Servian

Army, and bore upon his breast the ‘Gold Cross of Takovo' which he

received after the battles of the 28th and 30th of September, in

recognition of the heroism and bravery he displayed upon these eventful

days. The beauty of the decoration was enhanced by the circumstances of

its bestowal, for on the evening of the battle of the 30th, General

Tchernaieff approached Colonel Maclver, and, unclasping the Cross from

his own breast, placed it upon that of the Colonel.

“(Signed) Hugh Jackson.

“Member of Council of the League.”

In Servia and in the Servian Army Maclver reached what as yet is the

highest point of his career, and of his life the happiest period. He was

general de brigade, which is not what we know as a brigade general, but

is one who commands a division, a major-general. He was a great favorite

both at the Palace and with the people, the pay was good, fighting

plentiful, and Belgrade gay and amusing. Of all the places he has

visited and the countries he has served, it is of this Balkan kingdom

that the general seems to speak most fondly and with the greatest

feeling. Of Queen Natalie he was and is a most loyal and chivalric

admirer, and was ever ready, when he found any one who did not as

greatly respect the lady, to offer him the choice of swords or pistols.

Even for Milan he finds an extenuating word.

After Servia the general raised more Foreign Legions, planned further

expeditions; in Central America reorganized the small armies of the

small republics, served as United States Consul, and offered his sword

to President McKinley for use against Spain. But with Servia the most

active portion of the life of the general ceased, and the rest has been

a repetition of what went before. At present his time is divided between

New York and Virginia, where he has been offered an executive position

in the approaching Jamestown Exposition. Both North and South he has

many friends, many admirers. But his life is, and, from the nature of

his profession, must always be, a lonely one.

While other men remain planted in one spot, gathering about them a home,

sons and daughters, an income for old age, Maclver is a rolling stone, a

piece of floating seaweed; as the present King of England called him

fondly, “that vagabond soldier."

To a man who has lived in the saddle and upon transports, “neighbor”

conveys nothing, and even “comrade” too often means one who is no longer

living.

With the exception of the United States, of which he now is a

naturalized citizen, the general has fought for nearly every country in

the world, but if any of those for which he lost his health and blood,

and for which he risked his life, remembers him, it makes no sign. And

the general is too proud to ask to be remembered. To-day there is no

more interesting figure than this man who in years is still young enough

to lead an army corps, and who, for forty years, has been selling his

sword and risking his life for presidents, pretenders, charlatans, and

emperors.

He finds some mighty

changes: Cuba, which he fought to free, is free; men of the South, with

whom for four years he fought shoulder to shoulder, are now wearing the

blue; the Empire of Mexico, for which he fought, is a republic; the

Empire of France, for which he fought, is a republic; the Empire of

Brazil, for which he fought, is a republic; the dynasty in Servia to

which he owes his greatest honors has been wiped out by murder. From

none of these eighteen countries he has served has he a pension, berth,

or billet, and at sixty he finds himself at home in every land, but with

a home in none.

Still he has his sword, his blanket, and in the event of war, to obtain

a commission he has only to open his tin boxes and show the commissions

already won. Indeed, any day, in a new uniform, and under the Nineteenth

Flag, the general may again be winning fresh victories and honors.

And so, this brief sketch of him is left unfinished. To be continued.

Download the book "Under Fourteen Flags" (pdf)