|

The year Nineteen Hundred

and Fourteen will never be forgotten. Not only did it witness the

outbreak of the greatest war in history, but it marked a series of

anniversaries bearing on war. This wonderful year was the six hundredth

anniversary of the Battle of Bannockburn, which not only set Scotland

free, but forms a landmark in the art of war by showing that Infantry is

the backbone of an army. This year was the two hundredth anniversary of

the accession of the House of Hanover, which, by rousing a large part of

Scotland to arms on behalf of the Stuarts, made the subsequent

commandeering of the Scot for the purposes of national defence at once

timely—and timorous. And this year was the hundredth anniversary of the

Peace with France and with America, thereby closing down a prolonged

period of real national defence, which made Scotland feel acutely for

the first time the full price of the Union with England.

But although all these

historic events have an inter-dependent connection beyond the facile

similarity of date; although we are once more discussing for the

thousandth time the subject of defence and citizen service as a problem

of current politics; and although men are writing naval and military

history and compiling regimental records at a rate unknown to us

before—almost as if to checkmate the Angells who are piping for

Peace—this book has not been planned as a livre de circonstance, however

“ topical ” its appearance at this particular moment may be, except in

as much as none of us can escape from streams of tendency.

Nor has it been primarily

conditioned by my keen interest in the House of Gordon, which has

contributed so largely to the whole art of war. On the contrary, my

absorption in the family of Gordon has arisen from a previous and boyish

interest in soldiering, for I was writing, in 1887 and 1888, on the

history of the Wapinschaw, the Covenanting skirmishes in Aberdeenshire,

the Jacobites and the Volunteers before I ever tackled the enormous

subject of Gordon genealogy; and my immediate re-introduction to the

latter was the professional necessity of having to describe the part

played by the Gordon Highlanders in the capture of the heights of Dargai

in October, 1897.

But the subject of

soldiering had attracted me long before any of these things. One of the

earliest recollections of my childhood is a slender, blue-boarded

quarto, in the' centre of which stood a gilded isosceles triangle

bearing the words—spelt phonetically as if for nursery use—Ye Nobell

CHEESE-MONGER. At that time, of course, I did not know what an isosceles

triangle meant, or that the appellation “ Cheese-monger ” had any touch

of the ludicrous; but the first page of the volume, printed in colours,

was irresistibly comic to my childish eye. It showed a crowd of coatless

Lilliputians tugging grotesquely at ropes to pull down backwards the

martial-cloaked, cleanshaven figure of the Duke of Gordon from his

granite pedestal in the Castlegate; while another group in front was

engaged with equal enthusiasm in elevating towards the about-to-be

vacated site the figure of a dumpy man in a green uniform and bushy

whiskers, looking a little alarmed at the honour that was being thrust

upon him. I say this picture struck my childish fancy, not from the

retrospective standpoint of one of those psychological prodigies of Mr.

Henry James’s imagining, but because the anonymous artist, Sir George

Reid, had sketched unerringly an irresistibly comic situation, of which

the bearded Joey and Harlequin is the locus classicus. Besides this, the

rare occasions on which the book was shown to us—for it was one of six

copies produced (in 1861)—was enough to make the occasional perusal of

it something like a red-letter day; and,, furthermore, I used to “play

at soldiers” in a tunic and belt, with the word “Bon-Accord” on it,

which my father had worn as a fellow member with the aforesaid artist of

the Cheese-monger’s Volunteer corps.

In picturing the Duke as

a Prometheus, bound helpless before the advance of the Cheese-monger,

the satirist—it is strange that he rarely, if ever, again lent his pen

to humour—was instituting no comparison between the social status of his

Grace and the grocer. While he was primarily aiming at pitting the

amateur, the Volunteer, against the professional, he was also viewing

both from the standpoint of the civilian of that period, just as Punch

itself was doing; thereby, with a kefen, though perhaps unconscious,

sense of history, seizing on our traditional and deep-seated attitude as

a nation to the business of soldiering. To take but one example,

everybody knows the difficulty which was experienced in establishing a

Standing Army, for it figures to this day in the preamble of the Army

Annual Bill, by which the Army is rhetorically renewable year by year:—

“Whereas the raising or keeping of a Standing Army within the United

Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in time of peace, unless it be by

the consent of Parliament, is against the law?

As a people we do not

understand the Army qua Army; we recognise it as but one of the

instruments of State, the purpose of which is to uphold the honour of

the Nation. When that honour is not at stake, the instrument always

tends to become rusty. When danger arises, we begin sharpening the old

instrument and improvising new ones for the emergency; the South African

War was an absolutely typical example, and precisely the same thing has

been done in the war of 1914.

It is of such

improvisation that this volume treats. It is not a history of Highland

regiments like Stewart of Garth’s classic work. It is not an account of

Scotland’s military system from early times after the manner of Lady

Tullibardine in the case of Perthshire. It is not an application of Mr.

Fortescue’s 1803-1814 treatment of the County Lieutenancies; and it is

not a history of the Volunteers, the force to which we have come to

apply the term Territorial. It is an account of how two counties,

Aberdeen and Banff, contributed to the herculean efforts put forth by

the United Kingdom from 1757 to 1814 to extend her frontiers and to hold

what she already possessed. I have confined myself to these two counties

(except in including the two Strathspey regiments) because Kincardine

was always associated with Forfarshire and Elgin and Nairn with

Inverness, as Banffshire itself became in the matter of Militia. Indeed,

Aberdeenshire alone of the north-east counties has always been a

distinct unit.

I have used the word

Territorial,1 not in the modern restricted use

which connotes the old Volunteering, but because the whole effort of

recruiting—and not the subsequent tactical disposition of the forces so

raised—in the north during the period under review was conducted with a

frank recognition by the State of local conditions. First, in the dase

of Regular regiments it was carried out under the aegis of the great

territorial lords; later on, in the case of some of the Fencible

regiments, under the influence of professional soldiers who had some

local connection; then, in the case of the Militia, Volunteers and Local

Militia under the management of the Lord Lieutenants, with or without

the compulsive aid of the ballot. My last, main aim has been not to

describe the actual service of these forces when raised, but to show the

mechanism used to raise them, for, difficult as it is to find the data,

this is really the most useful fact for the modern reader to understand.

In this introduction I shall sketch the general principles under which

the various regiments in the north-east of Scotland from 1759 to 1814

were raised.

The spirit of

territorialism, not to say parochialism, was the pivot of this

mechanism; indeed, it was so dominating that the ultimate reason why the

mechanism was set in motion tended to become obscured. The opening

statement of Mr. Fortescue in his County Lieutenancies and the Army is

to a large extent true of Scotland— “The military system of England from

the close of the Middle Ages to the Nineteenth Century was practically,

though with superficial differences, the same. To every place which

required a garrison a small permanent force was indissolubly attached,

and for the purposes of war an army was improvised.” Thus a place like

Aberdeen had its “blockhouse,” under the control'of the Town Council;

and the Army, such as it was, was as visible, as local, a fact as any

other aspect of municipal control.

In the country districts

the laird became the pivot, and the raising of troops was as much a

personal matter as the levy of the old feudal lords in return for tenure

of land. The Highland regiments recall the fact to this day better than

any other type of troops, for they wear in their uniforms the mottoes

and the badges of the individual families concerned in their creation,

such as "Bydand” and the stag’s head of the Gordon Highlanders, and the

appearance of the arms of the company commanders, for the time being, on

the pipe banners. Many other instances might be cited ; suffice it for

the moment to say that the spirit of territorialism with all its

idiosyncracies conditioned, in varying degree, all the troops raised in

the north-east of Scotland during the period, 1759-1814, under review,

and it has been strongly reasserted on four subsequent occasions—the

raising of the Volunteers in 1859; Cardwell’s allotment of infantry

regiments to territorial recruiting districts in 1872 (when the Gordons

got “Bydand” and the stag’s head in lieu of the Sphinx and the word

“Egypt” for cap badge) ; Childers’ linked, or rather “welded,” battalion

system of 1881; and Lord Haldane’s Territorial and Reserve Forces Act of

1907, which aims at making national defence an integral part of local

government.

Now in view of these

facts it is very curious that soldiering has not been considered a

matter of real territorial interest among us. Nothing proves this point

more clearly than its meagre treatment in local newspapers and the

indifference shown by nearly all local historians —past masters of the

minute as they are—to anything dealing with defence, or what is called

“the military,” a phrase which sums up the separateness of the army from

citizenship. Thus a book like the late Mr. A. M. Munro’s history of Old

Aberdeen has nothing to tell us of the Aulton Volunteers; and Dr.

Cramond confined his reference to the subject in Banff to a nonpareil

note hidden away among the Town Council minutes. The irony of Sir George

Reid in “Ye Nobell Cheesemonger” was thoroughly characteristic of the

attitude of his period. Not only has the subject been treated with

indifference, but in actual practice soldiering for long encountered

active opposition. So far as Regular soldiering is concerned, every man

of middle age can recall that in his youth it was almost anathema, and

will recognise the verisimilitude of Mr. R. J. MacLennan’s wit in his

volume of Aberdeen sketches, In Yon Toon:—

Miss Macpherson—“It’s a

terrible thing aboot Mrs. Thomson’s loon, isn’t it?”

Mrs. Simpson—“O, fit was

that. I didna hear o’t.”

Miss Macpherson—“He’s

jined the sojers.”

Mrs. Simpson (raising her

hands heavenwards)—“Jined the sojers, has he? Eh, my good! An’ his

mither will be richt pitten aboot. Aye, an’ this her washin’ day, too.

Eh, my! ”

This point of view has

largely changed in recent years, and it would no longer be possible to

re-create a Nobell Cheese-monger; yet the spirit underlying such

incidents, and exhibiting antagonism to the centralised military ideal

has not been wholly exorcised, as the policy of the Aberdeen Town

Council on the use of the Links as a rifle range has served to show us.

That attitude is due to no unpatriotic contrariness; it is created by

local conditions, which were much more antagonistic in the period dealt

with by this inquiry.

It has therefore been far

from easy to get at data for the present volume, especially in reference

to the mechanism employed in raising troops. Luckily there is a large

number of documents at Gordon Castle dealing with the regiments raised

by the 4th Duke of Gordon, and I have to thank the Duke of Richmond and

Gordon for the privilege of examining them at my leisure. The charter

chests of other families engaged in raising men might furnish similar

papers, but I have not been able to get access to them. Such documents,

of course, tell us little or nothing about regiments once they had been

handed over to the State. Here we must consult the War Office papers now

housed at the Public Record Office, London; and extensive as the data

are, the wholesale destruction of documents in the past shows us that

the military authorities could be as indifferent as the civilian local

historian. The old system by which regiments kept their own records,

carting them about with other impedimenta, was thoroughly bad and

involved serious —and from some points of view, not

unnatural—destruction from time to time. Many of the documents that have

been preserved have not been seen by students. This was especially the

case with the series of Volunteer pay rolls, all of which had to be

specially stamped for me to examine, showing that they had never been

given out to the public before. I have also examined minutely the Home

Office series of documents known as “Internal Defence,” the trackless

desert of which was first traversed, and to such good purpose, by Mr.

Fortescue in The County Lieutenancies and the Army (1909), his journey

throughout the whole 326 volumes and bundles being, of course, much more

exhaustive and exhausting—he says it was “maddening” to write his

book—than one confined to two counties. These documents alone form my

excuse for dealing with the Militia and Volunteers, for both forces had

already been tackled by Colonel Innes and Mr. Donald Sinclair. That,

however, has only added to my difficulty, for I have had to incorporate

the new material without rewriting their work and thus cumbering space

needlessly.

The personal side of the

subject remains most imperfect in the absence of Description Registers

and the biographies of officers. To follow that up completely would

require a knowledge as extensive as Mrs. Skelton’s in Gordons under

Arms, plus a genealogical equipment such as probably no individual

scholar possesses. The greatest difficulty is presented by the

Volunteers, as if these officers had been shy of publicity, foreseeing

the ridicule cast by Mr. Meredith on the great Mel the tailor in

Evan Harrington) which was published in the very year that Sir George

Reid immortalised the Cheese-monger.

I am very well aware that

some of my conclusions on the influence of territorialism may be

regarded by some readers, especially professional soldiers, as highly

controversial. But there can be no doubt whatever that national

aspirations and local idiosyncracies largely conditioned the efforts to

raise troops in the middle of the eighteenth century. We are all

familiar with the facile theory that when Great Britain set out on her

sixty years of world-conquest in 1757, she had only to beckon to her

northern people and that soldiers sprang to attention like gourds, if

only because the spirit of military adventure satisfied the martial

hunger of a race that had been reared on fighting, but had been

deliberately starved for forty years by reason of its exploits on behalf

of Jacobitism. There could be no more misleading interpretation of

history, no greater blindness to the essential territorial fact, for the

simple reason that the half century of Union had not obliterated

Scotland’s individual consciousness; her point of view still differed

greatly from that of the dominant partner.

In the first place,

Scotland had been friendly on political, temperamental and dynastic

grounds with England’s traditional enemy, France. When the fruits of the

Union seemed likely to be spoilt by some of the Scots’ preference for

the essentially French line of Stuart, France had become unusually

friendly to these aspirations; so that we find a Scots officer, Thomas

Gordon, who had been transferred to the English Navy, deliberately using

his professional opportunities to make French aid to the Jacobites the

more available. But even if she had been inspired with the English bias,

Scotland was far removed from that strip of Channel which kept England

constantly on the alert. Indeed, so far from rousing Scotland, the sea

had a terrifying effect at any rate on the Highland levies, and more

than one mutiny arose out of the soldiers’ intense dislike, even horror,

of ships. When at last Scotland was threatened by France as part and

parcel of the United Kingdom, the danger, as the minister of Aberarder

plainly told the Duke of Gordon in a remarkable letter of 1778, was “too

remote” to make some of the inland districts worry. Indeed, from every

point of view, the reasons why Scotland should buckle on her armour

against France were far less obvious than in the case of England.

The reasons why Scotland

was not so predisposed as England was to take to soldiering went further

than the greater absence of motive. For ten years before the opening of

the great campaign for the possession of India in 1757, the best part of

warlike Scotland had been deliberately dispossessed of whatever arms she

possessed, the dominant partner being thoroughly frightened at the

possibility of another pro-Jacobite attempt, despite the fact that the

disarming Acts of 1716 and I725 had actually contributed to encourage

the hopes of the exiled house of Stuart. The Act of 1746 (19 Geo. II

cap. 39) “for the more effectual disarming the Highlands in Scotland”—an

extraordinarily “absent-minded” move seeing that the interrupted

campaign in the Low Countries against the brilliant Marshal Saxe was

being renewed at this very moment—was even more drastic, involving part

of Dumbarton and Stirling, and the whole of Argyll, Perth, Forfar,

Kincardine, Aberdeen, Banff, Nairn, Elgin, Inverness, Ross, Cromarty,

Sutherland and Caithness. The prohibition of the Highland dress—not

removed till 1782— was another blow in the same direction; while the

Heritable Jurisdictions Act of 1747 broke, up the feudal power of the

great landowners in such a way as to frustrate their later desire to

raise troops. The fear of the Highlanders rising again is brought out in

a letter which Lord Findlater wrote to the Duke of Newcastle on July 8,

1748 {Add. MSS., 32,715 f. 323) : —

It is said that ther is

an intention to turn the two Highland Regiments [the names are not

given] into Independent Companies to be sent to the Highlands. ... I am

sure it wou’d prove a most pernicious scheme, for it wou’d effectively

spread and keep up the warlike spirit there and frustrate all measures

for rooting it out. . . . It would be dangerous to scatter such a number

of military Highlanders in their own country. . . . No Highlanders ought

to be employed in the Highlands, but a small number of pick’d ones to

serve for guides for the regular troops.

The disarming edict

affected whole communities as well as individuals. Thus, Aberdeen was

deprived of its ordnance in 1745, lest it should fall into the hands of

the rebels, and this led to a strong protest from the Provost, July 11,

1759, when the coast towns were becoming frightened of France, all the

more as Regular troops had been withdrawn to fill up the gaps in our

scattered army. On July 12, 1759, the Lord Provost of Edinburgh, as

praeses of the Convention of Burghs, memorialised the Secretary of

State, Lord Holdernesse, as follows (.P.R.O.; S.P. Scotland-, series 2:

bundle 45: No. 59): —

The Burroughs of Scotland

which are situated on the East Coast from the river Tay northwards,

having represented to the annual Convention of the Royal Burroughs now

mett here, that in consequence of the orders given to the troops

gathered among them to march thither, they will be in a very dangerous

situation; for, being disarmed by law, they are altogether unable to

defend themselves from the enemy, who may attack them successfully even

with ships of very small force.

The Convention having

heard their representative, and being desireous that something may be

done for their safety and security while the troops are removed at a

distance, have directed me as their praeses humbly to lay their case

before your lordship.

We are far from

complaining of the measure of the removal of the troops, being sensible

that these orders have been given for weighty and good reasons. We only

beg your lordship will have the goodness to represent to our most

gracious Sovereign the present defenceless, and, therefore, dangerous

state of these burroughs, that he may be pleased to give out orders for

their safety as he shall see proper, and which the public security will

best admitt of. If a 40- or a 20-gun ship could be spared from the

service, and ordered to cruize from Fifeness to Buchanness, we are

hopefull that the evils we dread would hereby be effectually prevented.

But this we humbly suggest with the greatest submission.

Even when the luck turned

in our favour, as in the capitulation of Quebec, and after arms had been

sent—400 stand were given to the town in August, 1759 (W.O. i.,

614)—Aberdeen felt as nervous as ever, because the people did not know

how to use these arms. Thus, the Magistrates wrote to Holdernesse on

October 21, 1759 (Ibid. No. 84) : —

It is with great

reluctancy we presume to trouble your Lo’p. at this critical juncture,

when you are overburdened with publick affairs. But necessity obliges us

to have recourse to your Lo’p. for relieff and assistance, when we are

threatned with such immediate danger.

Your Lordship knows there

are no troops on the East Coast of Scotland betwixt the Murray ffrith

and the Frith of Forth, so that this town, being a place of the greatest

consequence for the number of its inhabitants and manufactures betwixt

the two ffriths, and situate centrically betwixt them in an open sandy

bay, where a number of troops could be landed in a very short space of

time, and so we are much exposed to the invasion of a forreign enemy,

and there is great reason to believe, may be the first place that will

be attacked. And tho’ His Majesty and the Ministry have been graciously

pleased to furnish us with some arms and ammunition, yet, our citizens

having been long out of use of arms, it cannot be expected that they are

in case to oppose a forreign enemy without the assistance of regular

troops.

We are making the best

use we can of the arms sent us, and are learning our citizens to the

proper exercise of them, and, were there regular troops to mix with

them, and animate them to action, we are hopeful they would do great

service.

As we are presently so

much exposed and in a defenceless state, we must implore His Majesty and

the Ministry to order a regiment of Regular troops to be cantoned along

our coast, and make this the head quarters, so as they may quickly

repair to any place that may be attacked. It will likewise be most

necessary to order as many as can be spared of the King’s Ships to

cruize along our Coast, and protect us against the invasion of a

forreign enemy with which we are daily threatened.

Not only was Aberdeen

robbed of arms, but it was deprived of the men who could have borne

them, for the memorial goes on to state:—

We have of late furnished

a vast number of men, as well for the land as the sea service, and gave

large bountys for their encouragement; and, as we pay our taxes

regularly, we humbly apprehend we are entitled to the Government’s

protection. And therefore we beg leave once more to implore His Majesty

and the Ministry to comply with this our most humble and earnest

request.

A case in point is quoted

in the Aberdeen Journal, March 16, 1756, which shows how compulsion was

forced on the local authorities:—

On Tuesday last [March 9,

1756] there was a very hot Press for mariners and seafaring men, which

was conducted with the greatest secrecy, vigilance and activity. The

Provost, having received Orders from # above, concerted the plan of

operation with Colonel Lambert, commanding Holms’s regiment here; and in

the forenoon of that day parties were privately sent out to guard all

the avenues leading to and from the town, as also the harbour mouth;

and, immediately before the Press began, guards were placed on all the

ports of the town. A little after two o’clock, the Provost, Magistrates,

Constables and Town Sergeants, with the assistance of the military, and

directed by Colonel Lambert, laid hold on every sailor and seafaring man

that could be found within the harbour and town, and in less than an

hour, there were about 100 taken into custody, and, after examination,

35 were committed to gaol as fit for service. Since that time several

more sailors have been apprehended, as also land men of base and

dissolute lives; and on Sunday last [March 14] were brought in from

Peterhead and committed to gaol six sailors who were sent to town under

a guard of General Holms’s regiment. There are now from 40 to 50 in

prison on the above account, and the Press still continues.

Nothing could show more

poignantly—if you have any imagination —the intense hunger for fighting

men; but this kind of raid appeased only one form of the hunger, namely

the clamant necessities of the State, which ran to earth any kind of

men, anywhere and anyhow. But it left two other maws, mainly local, not

only unsatisfied but more hungry than ever. If it appeased the great,

and mostly unseen, campaign of aggression carried on by the nation at

large, it neglected

the less showy

necessities of internal defence, leaving the coastwise communities

robbed of their manhood, and consequently panic-stricken at the thought

of invasion. Then it starved the great landlords, who for very definite

reasons of their own were beginning to raise regiments from among their

vassals, very much as the feudal squires had been doing centuries

before, and who found men increasingly difficult to get, until at last

their personal and financial resources became thoroughly exhausted in

the process and their task had to be taken up by the local authorities.

Faced by the local fact,

the Government at last began attacking the problem, so far as the north

was concerned, on much more sympathetic lines by recognising that

territorial needs must be met by territorial means and that it was

highly advisable to raise infantrymen by consent instead of by the

hole-and-corner and antagonising tyranny of the Press Gang for a service

which was really alien to the genius of the people.

"The new policy was

opened in 1757, the year after the Press Gang raid which I have

described, which witnessed the inauguration of Clive’s decisive campaign

in India. The old fear of Jacobitism was going (as we see by the

interesting fact that even old Glenbucket’s grandson, William Gordon,

was granted permission by the Sheriff Depute of Banffshire to wear arms

again), and the new hope of arming the Highlanders for the service of

the State was begun. On January 4, 1757, the Hon. Archibald Montgomerie,

nth Earl of Eglinton (1726-96) got a commission to raise a regiment (the

77th), while the 78th was raised by the Hon. Simon Fraser, de jure 12th

Lord Fraser of-Lovat (1726-82), under commission dated January 5, 1757.

Of course, neither Montgomerie nor Fraser invented the idea of utilising

the Highlander for soldiering. That must be credited to the Black Watch

which, I believe, Mr. Andrew Ross is right in tracing back, not to 1725

as Stewart and all his imitators state, but to 1667, when the 2nd Earl

of Atholl got a commission to raise men to be a constant guard for

securing the peace in the Highlands, and “to watch upon the braes.” .

The idea had also been taken up again in 1745 when the 4th Earl of

Loudon raised a Highland regiment which fought at Prestonpans and was

afterwards taken to Flanders. But the Rebellion put a complete end to

this kind of military experiment, and nothing more was done until 1757,

when Montgomerie and Fraser got their commissions to raise two Highland

regiments of the line, the 77th and 78th, to help the nation in the

ambitious adventures afoot on the Indian and Canadian continents.

The necessity of the

nation was just the opportunity that the Highland chiefs wanted.

Montgomerie, of course, was a Lowlander, though he was connected by

marriage with the Highlands, and had always been loyal. But Fraser had

been reared in the atmosphere of rebellion, and had served under the

Prince in the ’Forty-Five, being attainted like his father, the

notorious Lord Lovat. The rebel chiefs had come to see that something

more was necessary than a sulky acceptance of the new House of Hanover;

they felt that they must do something positive ; and their territorial

position, even if the feeling of clanship was on the wane* gave them the

chance of helping the State in its great hour of need.

Montgomerie tapped

Aberdeenshire for two companies—one of them being commanded by a son of

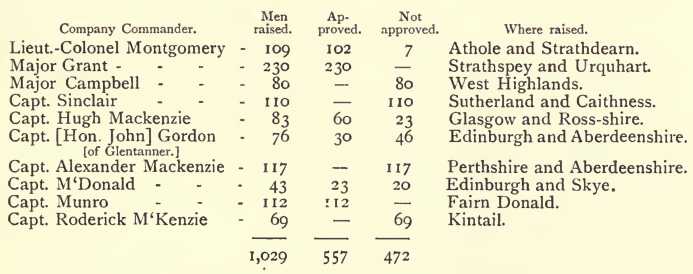

the 3rd Earl of Aboyne—as we learn from the “state” of his regiment,

dated Nairn, March 9, 1757 (W.0. 1 : 974)- The amazing point about this

return, which shows 10 companies, is the number of men rejected, 472

recruits being “not approved ” out of a total of 1,029.

“The draughts intended

for sergeants and corporals are not included in the above return.”

Fraser kept more to his

native county of Inverness, but he, too, had a Gordon officer—Cosmo

Gordon, of unknown origin, who was killed at Quebec in 1760.

Nothing more was done for

two years; but in 1759 the growing necessities of the situation—the

compaigns against the French in India and Canada, and the threat of

invasion—called for further efforts. The Secretary at War, Lord

Barrington, issued a memorandum which strikingly illustrates the

clamorous need for soldiers {Add. MSS. 32,893, f. 62):—

Whereas the King’s

Dominions are publickly threaten’d to be invaded by the French, who are

making great and expensive preparations for that purpose: And whereas

some of His Majesty’s Corps of Troops in Great Britain are not so full

as at such a juncture might be wish d, especially at a season of the

year when it can not be expected that they should be immediately

compleated by the usual methods of recruiting;

Declaration is hereby

made that any man may inlist in the Army on the following conditions:

He shall not upon any

account or pretence whatever be obliged to go out of Great Britain, even

tho’ the Regiment wherein he serves should be sent abroad :

He shall be intitled to

his discharge on demand at the end of the War, or sooner in case it

shall appear to His Majesty that the French have layM aside their

design! of invading Great Britain.

The North tackled the

problem much more energetically by raising three totally new

regiments—the 87th (Keith’s); the 88th (Campbell of Dunoon’s) ; and the

89th (the Duke of Gordon’s). It is with the last that I start this book,

for though Aberdeenshire contributed both to Montgomerie’s in 1757 and

to Keith’s, the 89th was the first complete corps produced by the

north-east of Scotland. I may add that I have gone into the foreign

service of the 89th at greater length than that of any of the other

regiments dealt with for the simple reason that it has hitherto been

much neglected by military historians, although it did excellent work in

India under Hector Munro.

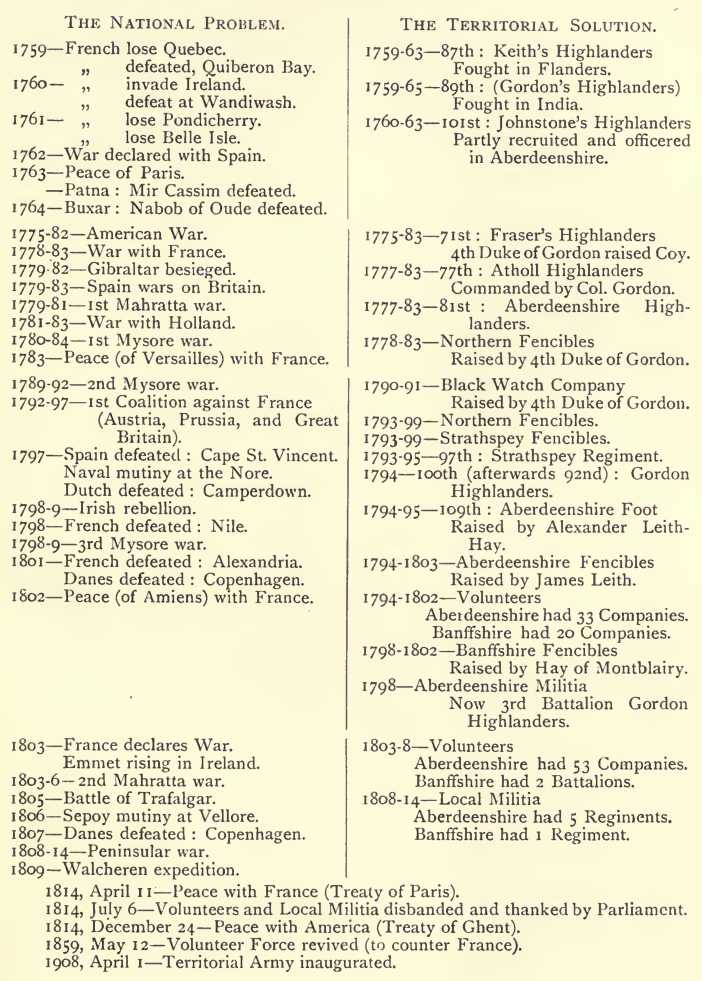

From the moment in 1759

when these big efforts were put forward, down to 1814, when the Peace

with France and with America called a long halt, the north-east of

Scotland was perpetually thinking of soldiers. The necessities of the

national situation synchronise exactly with local efforts as the

following parallel statement of outstanding events prove:—

Such were the vast

enterprises undertaken by the State, and such the aid afforded by our

district. On the one hand you find a grandiose Foreign Policy (the one

local newspaper contained little else than foreign “ intelligence,” its

information about the soldiering that was going on being of the most

meagre kind); on the other, you are confronted, and some readers may be

bewildered, by an extraordinary particularism, based on a complete, and

perhaps necessary, submission to local conditions. This, of course, was

not the monopoly of the district; it was national; for, if Seeley’s

doctrine of the absentmindedness of our “expansion” seems too obvious to

some critics, there can be little doubt that the policy of defence was

one long series of experiments in the art of opportunism to suit the

ideals of an island race, reaching a climax in 1803 in Addington and his

Secretary for War, Lord Hobart, whose “blindness,” “weakness” and

“folly,” evoke the wrath of Mr. Fortescue. The War Office was

conditioned by this particularism, by the mental outlook of the Scot in

general and the Highlander in particular, first in the matter of getting

men, and secondly in the art of keeping them once they had been got; and

the authorities had to pay a heavy price for any attempts, conscious or

not, to over-rule local sentiment.

First, with regard to

getting men, the State was confronted by everything making for

clannishness. It must be remembered that the Highlanders were

essentially home birds, devoted to their own district, to their own

friends and leaders; the world-famous wandering Scot was almost

exclusively of the Lowland type. The Celt’s love of his native soil,

which has informed so much of our politics, and which is so finely

expressed in the “ Canadian Boat Song,” was so intense that it strongly

militated against the success of such a small adventure as the Jacobite

march to Derby, even though the clans were intensely interested in the

main object of the exploit. Therefore when they were asked to support a

scheme in which they did not feel themselves personally involved and

which meant not merely a departure from their native glens but a journey

across the seas, it became very difficult to induce the Highlanders to

support it. If they agreed to go, it was only on condition that they did

so with the people they knew and under the command of the leaders they

respected, so that casual recruiting among them would have been next to

useless; you had to recruit the whole clan, as it were, and establish a

Highland Regiment, which considered itself as much a unity in the heart

of the whole army as a foreign embassy remains inviolable territory in

the capital in which it is placed. This feeling remained potent for a

long time after the original impulse of the Highland regiments had

become obscured. A picturesque example of it is cited by Sergeant

Robertson in his interesting Diary. Speaking of the Battle of Orthes

(February 27, 1814) he says (p. 129): —

Here the three Highland

regiments met for the first time—namely the 42nd, 79th and 92nd; and

such a joyful meeting I have seldom witnessed. As we were almost all

from Scotland, and having had a great many friends in all regiments,

such a shaking of hands took place. The one hand held the firelock and

bayonet, while the other was extended to give the friendly Highland

grasp, and the three cheers to go forward. Lord Wellington was so much

pleased with the scene that he ordered the three regiments to be

encamped beside one another for the night as we had been separated for

some years, that we might have the pleasure of spending a few hours

together and make inquiry about our friends and to ascertain who

survived and who had fallen.

But even within a

Highland regiment there were differences between different septs to be

reckoned with, so that we find groups of men of one surname declining to

march to a rendezvous with groups of men of a different name, with whom

there may have been long outstanding controversies. And when they

reached such a rendezvous there were cases—even so late as 1793, as the

Northern Fencibles had to reckon with—when a Highland officer demanded

that the men he had raised should be confined to his company, the

military exigencies of distributing men over the whole regiment being

quite incredible to him. Another great difficulty in getting men arose

out of the jealousies of the leaders who set out about raising

regiments. The War Office did not raise them, in the beginning at least,

directly. It assigned the task to individual magnates, under licence,

and simply took over the regiment when completed. How the regiment was

actually gathered together was a matter of small concern to the War

Office. The consequence was that rival recruiters vied with each other

in offering inducements, so that bounties increased with the necessity

for troops until the price rose in some cases to as high as £50 and £60

a head. One recruiter would invade the territorial domain of another and

annex men by hook or by crook, local jealousies being fanned to a

sort of civil war—waged,

ironically enough, because of the common enemy of the State.

Aberdeenshire affords two striking cases in point —the conflict in 1778

between the Northern Fencibles, raised by the Duke of Gordon, and the 81

st Regiment, raised by his kinsman, the ca * Hon. William Gordon. Again

in 1794 the Duke was seriously hampered in raising the Gordon

Highlanders by the efforts put forth by Leith-Hay to raise the 109th,

the houses of Gordon and of Leith rallying round their respective

leaders, while the Corporation of Aberdeen inclined to favour Leith-Hay.

Both the 81st and the 109th soon disappeared, but that was because the

influence of their organisers was not sufficiently strong with the

authorities, as the Duke’s was, to keep them going. The story of these

conflicts, represented of course entirely by private documents and not

in the War Office archives, makes extraordinary reading. It need hardly

be said that human nature took full advantage of such a situation, until

recruiters were faced by all sorts of V' compulsions from their quarry.

For instance, small farmers would agree to give a son in return for an

enlargement of their holding, or a greater security of tenure or some

similar quid pro quo; while the laird also would exercise pressure by

threatening tenants guilty of small offences, such as annexing wood or

game, or doing something that was more or less punishable. It is

necessary to underline these facts because Stewart of Garth, who has

been copied by nearly every writer on the subject, gives a point blank

denial. Ever on the defensive so far as the Highlanders were concerned,

he lays it down (Sketches of the Highlanders, ii., 308) : —

It has been alleged that

these services [of tenants in the field at the call of the lairds] were

not unbought, as the sons of tacksmen and tenants were sent by their

parents to fill up the ranks of Highland regiments on a direct or

implied stipulation of abatement of rent, or on some pecuniary or other

advantage to be received, for the service of the youths who came forward

to take up arms at the call of their chiefs and lords. Circumstances do

not confirm this view of the subject.

In reply to which you

have only to read the letters sent to the Duke of Gordon by tenants in

purely Highland districts; letters which I have little doubt could be

matched by others in the charter chests of the great landlords, for

there is no reason to believe that the Duke’s tenants were more worldly

wise than those of other landlords.

If it was difficult to

raise men, it was nearly as difficult to retain them, even when they

passed into the keeping of the State. For a long time, indeed, the

Highlanders were unable to differentiate the two factors—the individual

subject who induced them to join and the nation as a whole for which

their services were required. The State spoke through the voice of the

individual, and the individual was expected to keep to the terms which

he proposed, and which tended to vary with national exigencies. Here we

see an inevitable clash between national temperaments, between the

Scot’s logicalness and the inherent opportunism of the dominant partner,

just as strong to-day as it was then, when the force of events made it

almost necessary. Thus, if a regiment was raised on the n Fencible plan

to serve in Scotland and an attempt was made to march it across the

Border or transport it to Ireland, the rank and file simply declined,

greatly to the amazement of a man like Colonel , Woodford, commanding

the Northern Fencibles of 1793, who had been ' trained in the obedient

school of the Grenadier Guards. In the case of regiments of the line,

attempts made to draft men from one corps to another were equally

repudiated, while the efforts to get the Highland corps to sail abroad

led to open mutiny. The classic case is that of J the Black Watch in

1743, which has been set forth so sympathetically by Mr. Duff MacWilliam.

The War Office, applying the legal standard, shot three of the resisters

and drafted a great many of them—“victims of deception and tyranny,” to

whom Mr. MacWilliam proudly dedicates his book. “The indelible

impression” which this made on the minds of “the whole population of the

Highlands, laid,” as Stewart of Garth is bound to admit, “the foundation

of that distrust in their superiors which was afterwards so much

increased by various circumstances.” A full corroboration of Stewart’s

statement occurs in the remarkable letter written by the minister of

Aberarder in 1778, to which too much attention cannot be paid : —

The people have been

successfully deceived since the middle of the last war by all the

recruiting officers and their friends. It has constantly been, since

that period, the common cant that the recruits were only enlisted for

three years or a continuance of the war; yet, they saw or heard of those

poor men being draughted into other regiments after their own had been

reduced, and thus bound for life, instead of the time that they were

made to believe. . . . The people will not be convinced, not even by

giving them written obligations. . . . They have been so often cheated

that they scarce know when to trust.

So disastrous indeed was

the effect of penalising the Black Watch, that when the Atholl

Highlanders, commanded by the Laird of Farskane, took up the same

attitude exactly forty years later, Parliament and the authorities

declined to punish a single man. Intensely pro-Highland and patriotic,

and imbued with the theirs-not-to-reason-why of the old soldier, Stewart

is compelled to devote a whole chapter to eight of these mutinies—“very

distressing events ” he calls them —extending from 1743 to 1804; and his

whole tone is that of sympathetic apology for the “peculiar disposition

and habits of the Highlanders.”

One of these

“peculiarities” was a fierce resentment against the infliction of the

brutal punishments then meted out to soldiers. Stewart insists again and

again that Highlanders had to receive preferential treatment, not so

much because their “ crimes ” were less serious, but because their

temperament made such expiation highly prejudicial to the State’s chance

of gaining the services of their countrymen. He maintains for instance

(ii., 313) :—

The corporal punishments

which are indispensable in restraining the unprincipled and shamelessly

depraved, who sometimes stand in the ranks of the British Army, would

have struck a Highland soldier of the old school with a horror that

would have rendered him despicable in his own eyes and a disgrace to his

family and name. The want of a due regard to, and discrimination of,

men’s dispositions has often led to very serious consequences.

The more minute

investigations of modern historians completely corroberate Stewart’s

attitude.

It is extremely important

to note that even after the territorial organiser of a regiment had

placed his corps on the “ Establishment,” his influence with the men

remained and was made use of. Thus, when Colonel Woodford failed to make

anything of the Northern Fencibles, he had to send post-haste to Gordon

Castle for his brother-in-law, the Duke of Gordon, to go south and

pacify the men; and similarly when the Strathspey Fencibles became

restive at Dumfries in 1795, Sir James Grant, who had raised the

regiment, was sent for, “but unfortunately he arrived too late.”

A City of Aberdeen

Regiment Declined.

So far, I have been

dealing with regiments raised under the personal influence of the great

landed magnates; for little was done to encourage corporate bodies. A

striking case of this refusal was experienced by the City of Aberdeen,

which got thoroughly alarmed like the rest of the country after the

disastrous surrender of Burgoyne at Saratoga in October, 1777. Early in

December the town of Manchester volunteered to raise a battalion of

eleven hundred men at its own expense. Liverpool shortly afterwards

followed this example, and was immediately imitated by Glasgow,

Edinburgh and Aberdeen, and the offers of all except Aberdeen were

accepted. The Aberdeen offer4 was forwarded to

Lord Suffolk, the Secretary of State for the North, by Provost Jopp on

January 10, 1778, as follows (Aberdeen Town Council Archives):—

My Lord,—The City of

Aberdeen, having on many occasions'* given the strongest assurances of

their zeal and attachment towards His Majesty’s person and government;

and having beheld with indignation the rise and progress of a rebellion

and revolt in the British Colonies in America, which seems to be grown

to an alarming height:

Have resolved at this

critical juncture most humbly to offer to His Majesty every assistance

in their power for the better enabling Government to prosecute with

vigour the American War and for reducing the rebellious Colonies to

their former state of allegiance and subordination. And I have the

honour to inform your Lordship that they have opened and are now

carrying on successfully and with all possible dispatch a subscription

for the purpose of raising a body of men for His Majesty’s Service.

I have taken the liberty

to inclose for your Lordship’s perusal a Memorial on this subject, and

have to request that your Lordship will be pleased to lay the same

before His Majesty for his gracious acceptance. If this Memorial should

contain anything improper, it must be imputed to my having had no

opportunity of knowing what conditions Government has been pleased to

allow other Corporations in like cases.

I must beg leave to

remark to your Lordship that the circumstances of a new corps [the 8ist

Regiment] of one thousand men to be raised by Colonel [the Hon. William]

Gordon, whose officers are mostly named from this corner and county, may

render the immediate procuring of recruits more difficult, and may

require that the period for completing any corps we may be able' to

raise be not limited, or at least not to a very short space. At the same

time, assuring your Lordship that every effort will be made for carrying

this design into execution with all possible dispatch; we hope that your

Lordship will be pleased to signify to us His Majesty’s pleasure as soon

as may be.

The City’s proposals were

embodied in the following memorial: —

1. That a body of men

shall be enlisted at the expense of this City to be put upon the

Establishment as a separate Corps, provided they shall amount to 500 or

upwards, and, if under that number, to be embodied in Independent

Companies.

2. That the community be

allowed to recommend officers who are to be approved by His Majesty,

vizt.; If 500, a Lieutenant-Colonel Commandant, Major, Captains and

Subalterns for the different Companys; it being understood that no

Officers above the rank of Lieutenants shall be recommended but such as

are of approved merit and have served with reputation in the Army,

several of whom have already offered their services on this occasion.

3. If 700 or upwards, a

Colonel, Lieutenant-Colonel, Major, etc.

4. Pay to commence from

the time allowed to other Corps now raising.

5. Cloathing, arms, etc.,

to be furnished by Government.

6. The Order from War

Office for inlisting to be addressed to the Provost of Aberdeen with the

ordinary power of delegation.

N.B.—In order to be able

to procure men with more facility, might engagement be made that such as

desire it may have a discharge at the end of the American War ?

To this enthusiastic

offer, Lord Suffolk returned a polite refusal on January 23, 1778 : —

Having had the honor of

laying before' the King your letter of the 9th [sic] inst. with the

Memorial enclosed in it, I am now to inform you that the fullest sense

is entertained of the zeal and attachment of the City of Aberdeen

towards His Majesty’s person and government as well as of the

constitutional principles which induce the Corporation to the proposal

of enlisting a body of men at their own expense to be put upon the

Establishment as a separate Corps.

As, however, it is not at

present intended to accept any new levies beyond what are already under

the consideration of Parliament, I am on this account to decline the

offer: at the same time that I once more assure you on the justice done

to the loyal and constitutional motives from which it originates.

The Fencible Movement

of 1778 and 1793.

To anyone who considers

the magnitude of our operations at this time and the complications

arising out of France’s alliance with America (February), with the

declaration of war on us (July 10, 1778), the refusal of the Government

to accept the help of Aberdeen may seem extraordinary. As a matter of

fact, it was thoroughly typical of the hugger-mugger, hand-to-mouth

management of our military preparations throughout the whole period. It

is true that the new levies to which Suffolk referred included twelve

regiments of the line—the 72nd to the 83rd inclusive—of which nine were

Scots, but it is also true that for some time before this date the

difficulty of getting men had been growing so acute that a compulsive

measure, known as the Comprehending Act (18 Geo. III. cap. 53), had to

be passed; and a less exigent type of troops, the Fencibles, was raised,

in the absence of Militia, which Government declined to allot to

Scotland till 1797, though England had had its Militia Act in 1757. One

of these Fencible regiments was raised in 1778 by the 4th Duke of

Gordon, who found out that nineteen years of Regular soldiering had more

or less satisfied his vast tenantry. The conditions of service in the

Fencibles were voluntary enlistment (for a Government bounty of three

guineas per man). The service was confined to Scotland, except in the

case of the invasion of England. The men were not to be drafted; and the

officers were to be chosen by the raiser of the regiment. Perhaps it was

the belief in the discrimination of the individual magnate to choose

good officers, as compared with the conflicting views of a corporation,

that made Government favour the recruiting proposals of the former; in

any case, the State’s refusal was not a happy way to treat municipal

enthusiasm, and may account for much of the antagonism that has not

infrequently existed between the War Office and Town Councils.

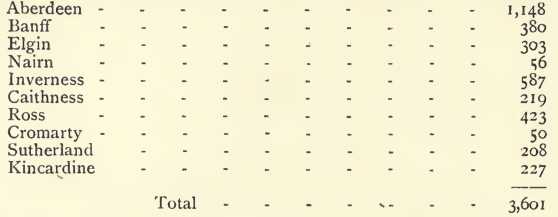

In 1782 a bill was

introduced into Parliament “ for the better ordering the Fencible Men in

that part of Great Britain called Scotland.” It provided for 12,500

privates being “annually formed into corps, companies, and battalions to

learn the use of arms, and to qualify themselves in case of actual

invasion, or rebellion existing within Great

Britain, to march out,

and act within Scotland, against any rebels and invading enemies.” The

quotas of the northern counties were:—

This spurt in regiments

lasted only five years, for with the Peace of Versailles, 1783, many

regiments were disbanded, including the 77th, the 81st, and the Northern

Fencibles, and then the old laxness set in until the next crisis ten

years later. The situation has been admirably summed up by Mr. Fortescue

(County Lieutenancies, p. 3):—

From 1784 until 1792 Pitt

allowed the military forces of the country to sink to the lowest degree

of weakness and inefficiency, and in 1793 he found himself obliged to

improvise not merely an army, but, owing to the multiplicity of his

enterprises [with Austria and Prussia against France], a very large

army. He fell back on the old resources of raising men for rank [which

signified the grant of a step of promotion to all officers and of a

commission to all civilians who would collect a given number of men],

and calling into existence new levies, allowing the system to be carried

to such excess that the Army did not recover from the evil for many

years. Never did the crimps reap such a harvest as in 1794 and 1795 ;

and never was a more cruel wrong done to the Army than when boys fresh

from school, in virtue of so many hundred weaklings produced by a crimp,

took command of battalions and even of brigades, over the heads of good

officers of twenty and thirty years’ standing. In 1793, the bounty

offered to men enlisting into the line was ten guineas; within eighteen

months the Government was contracting with certain scoundrels for the

delivery of men at twenty guineas a head, and long before that the

market price of recruits had risen to thirty guineas.

The new crisis in

national affairs was met by the raising of twenty-two corps of

Fencibles, including the Duke of Gordon’s Northern Fencibles and James

Leith’s Aberdeenshire Fencibles; and a great many regiments of

Regulars—thirty thousand were enlisted between November, 1793, and

March, 1794—to which the North-East contributed the 100th (Gordon

Highlanders) and the 109th. Besides that, a totally new force was

created in 1794, namely the Volunteers, which I shall describe more

particularly later on. In addition to these, Sir James Grant raised the

97th and the Strathspey Fencibles, which, though rather out of our

district, have been included because the Grants were rivals of the

Gordons and because both these corps exhibit strong traces of the

vicious system to which Mr. Fortescue refers. The method of raising men

for rank had hitherto been confined to Independent Companies, and had

therefore led to no higher rank than that of Captain. But it was now

extended to the raising of “ a multitude of battalions, which, for the

most part were no sooner formed than they were disbanded and drafted

into other corps,” thereby showing that the personal principle animating

the earlier territorial corps had broken down. Mr. Fortescue describes

the vicious situation (British Army, vol. iv., part i., p. 213):—

The Army-brokers . . .

carried on openly a most scandalous traffic. “In a few weeks,” to use

the indignant language of an officer of the Guards, “they would dance

any beardless youth, who would come up to their price, from one newly

raised corps to another, and for a greater douceur, by an exchange into

an old regiment would procure him a permanent situation in the standing

Army.’'

The evils that flowed

from this system were incredible. Officers who had been driven to sell

out of the Army by their debts or their misconduct were able after a

lucky turn at play to purchase reinstatement for themselves with the

rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. Undesirable characters, such as keepers of

gambling houses, contrived to buy for their sons the command of

regiments; and mere children [you may remember the story of the

baby-Major “greetin’ for his parritch ”] were exalted in the course of a

few weeks to the dignity of field officers. One proud parent, indeed,

requested leave of absence for one of these infant Lieutenant-Colonels

on the ground that he was not yet fit to be taken from school.

The Gordon

Highlanders.

In this sordid and inept

welter, the Gordon Highlanders, first numbered the 100th and then the

92nd Regiment, stand forth with flying colours; and remain with these

colours flying to the present day; whereas their immediately local

rivals, Grant’s 97th and Leith-Hay’s 109th, vanished a few months after

they were raised, as victims of the vicious system by which they were

partly officered. Indeed, of all the many regiments raised in our

district in the period under discussion the 92nd with the Aberdeen

Militia alone have survived, and few British regiments have captured the

public imagination like the Gordons.

I should like to add one

word of explanation about this distinction. It has been said that the

fame of the Gordons is due to the indiscriminating praise of “Cockney”

war-correspondents, especially at the time of Dargai. It has also been

hinted that my own work on the house of Gordon has had an influence in

“booming” the regiment. Both suggestions only prove the inadequate

historical equipment of critics who make them. The Gordon Highlanders

from the very first have been popular, and have always been “ boomed.6

The best proof of this statement is to be found in the bibliography

appended to the present volume. The 75th Regiment, now forming the 1st

Battalion of the Gordons, came into existence in 1787, seven years

before the 92nd. It has had a splendid fighting career; and yet not one

single monograph, not even of pamphlet size, has been written about it.

Almost the only attempt to tell its story is that made by

Lieutenant-Colonel Greenhill Gardyne in his Life of a Regiment, where he

devotes some chapters to the old 75th as the 1st Battalion of his main

subject. The same holds true of the iconographia of the two corps, for

beyond Eschauzier’s print of 1833 there is scarcely a picture of the

75th.

Why should this be the

case? The Gordons are not the oldest Scots regiment; they do not possess

the longest “ honours ” ; they have not been unduly praised by Aberdeen

writers—rather, indeed the contrary, for we pride ourselves on our sense

of proportion, and it is only of comparatively recent years that the

Gordons have been intimately associated with their present depot. The

main reason of their popular fame is that they have always had the touch

of personality about them, and have not merely been a unit in an

indiscriminating military organisation. This personal touch was imparted

to them with the raising of the regiment, which was enthusiastically

forwarded by the Duke of Gordon and all the members of his family,

notably by his brilliant consort, Jane Maxwell, who is said to have

kissed the recruits. Whether that is true 01* not, it has become an

integral part of a sort of saga, and is now boldly illustrated in the

official recruiting literature of the regiment. The personal touch was

continued by the service of the Duke’s popular and handsome heir, the

Marquis of Huntly, immortalised in Mrs. Grant of Laggan’s “Highland

Laddie.” Again, this personal feeling was greatly aided by the fact that

the first recruits were to a large extent Highland, and the officers

have been mostly Scots. The Gordons, indeed, are to my mind a splendid

example of what the best type of territorialism can do for a regiment—to

preserve traditions and esprit de corps, and to ensure a continuity and

preservation of individuality, which are of first rate value in forming

the character of a regiment in the British Army.

The Grampian Brigade.

Before passing on to the

next type of military force which was raised, namely the Militia,

reference must be made to an abortive scheme to raise a new combination

of Highlanders, which was to be called the Grampian Brigade. Nominally

promulgated by the Duke of York, it was forwarded on February 22, 1797,

as a circular letter to the Duke of Gordon by his great friend, Dundas,

then Home Secretary (Gordon Castle Archives') : —

I submit to your Grace’s

view a plan which the Duke of York has put into my hands. I own I was

very much struck on the perusal of it.

Perhaps at the time the

laws were made for restraining the spirit of clanship in the Highlands

of Scotland the system might be justifiable by the recent circumstances

which gave rise to that policy. It has for many years been my opinion

that those reasons, whatever they were, have ceased, and that much good,

instead of mischief, may on various occasions arise from such a

connexion among persons of the same Family and Name. If this sentiment

should be illustrated by the adoption of any such measure as the

accompanying paper suggests, I shall have reason to be still more

fortified in that opinion. I have not, however, thought it right to give

His Royal Highness any advice on the subject without having some ground

to judge how far there was a likelihood of its being carried into

existence. The most obvious method of doing so is by addressing myself

to your Grace and to other persons suggested as the proper cements [sic]

of the different classes of Families referred to.

If the plan takes place

it does not occur to me there can be any reason of distinguishing such a

levy as this from other Fencible corps in respect of establishment and

pay.

The Plan was to raise

16,000 men for internal defence by embodying the Highland Clans to be

employed in Great Britain or Ireland in case of actual invasion or civil

commotion or the imminent danger of both or either. Each clan was to be

formed into distinct corps not exceeding 600, nor less than 200 private

men in each.

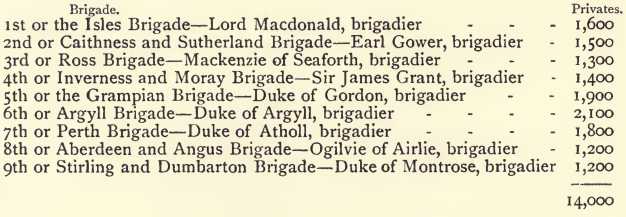

There were to be nine

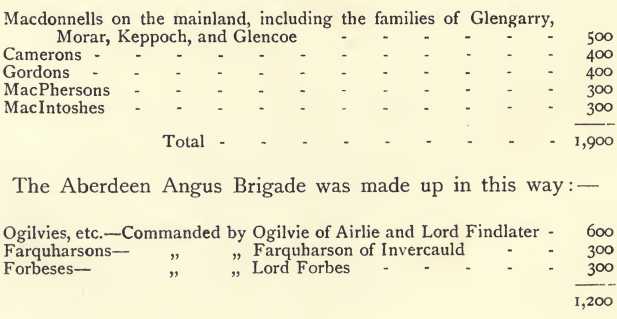

separate brigades, utilising the clans in the following proportions: —

The 5th or Grampian

Brigade, 1,900 strong, with the Duke of Gordon as brigadier, was to be

constituted thus : —

The Plan was accompanied

by some explanatory “ remarks ” disclosing the theory underlying it: —

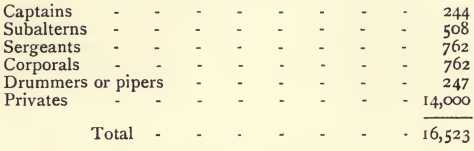

The total of officers

and men in the nine brigades and 40 battalions was to be :—

The Plan now proposed for

embodying the Highland Clans is formed upon the principles which seem

calculated to obtain the unanimous approbation of all ranks of people in

the Highlands and to make it a popular measure.

The Highlanders have

been, and still are, warmly attached to their Chiefs and ancient

customs, particularly in regard to the ranking and marshalling of the

Clans. The present arrangement completely embraces these views, as each

Clan forms a distinct Battalion, commanded by their natural Chief or

Leader, more or less in a number according to the strength of the Clan,

whilst the dignity of the great Chiefs and proprietors is equally

supported by placing each at the head of a Brigade.

Considerable attention is

also paid in forming each Brigade of Clans which are naturally attached

from local situation or otherwise co one another, as well as to their

Brigadier.

From the ordinary

avocations of the Highlanders in general it is obvious that no equal

number of men in any one district in the Kingdom can be employed with so

little injury to agriculture and manufactures. At this moment they may

be justly considered the only considerable body of men in the whole

kingdom who are as yet absolutely strangers to the levelling principles

of the present age, and therefore they may be safely trusted

indiscriminately with the knowledge and use of arms.

They admire the warlike

exploits of their ancestors to a degree of enthusiasm ; and, proud to

see the ancient order of things restored, they will turn out with

promptitude and alacrity.

As all the Clans have a

number of men in the present Fencible Regiments, each Chief will be

allowed to complete his serjeants and corporals from among his kinsmen

in those corps for the purpose of drilling his battalion expeditiously;

and, moreover, that each regiment may be furnished with some officers of

knowledge and experience, the Chiefs will be permitted to take a certain

proportion of their Officers from the Line, or the half pay list. This

will be attended with no difficulty, as there is no Clan which has not a

number of gentlemen in the Army; and in order to induce officers of the

Line to enter into the Clan levy, it will be a subject for consideration

whether one step of promotion may not be given to them. It will,

likewise, be subject for future consideration what the rank of the field

officers commanding corps shall be, and what the proportion of staff

officers shall be to each corps.

When the Duke received

the scheme, he immediately transmitted it to the chiefs of whom he was,

as it were, the superman, and he did so in a thoroughly tentative

spirit, for the time had long gone past when he could ride roughshod

over them as his ancestor, the first duke, had done. The replies of the

heads of the great Highland families on his estates—namely, the

Macphersons, the Mackintoshes, the Macdonnells, and the Camerons—must

have soon convinced him that the scheme would not work. These documents

are remarkably interesting. Macdonnell, dating from Glengarry House,

March 7, was cautious:—

Having seen only parts of

the Plan, [I] must defer remarks for the present, as I purpose doing

myself the honour of waiting on your Grace in about twelve or fourteen

days hence at furthest.

Macpherson, dating from

Cluny, March 6, was sceptical: —

Your Grace must be very

sensible that this country has already been much drained by different

levies—so much so that, if the number now proposed were taken out of it,

there would be a great danger of a totall stop being made to the

operations of husbandry; and, tho’ I have not the smallest doubt of the

loyalty of the inhabitants, I have my fears that they would not readily

agree to leave their homes in the manner proposed. But if the Plan of

enrolling into volunteer companys be thought a good measure, I have no

doubt (should there be no interference) that six companies of 50 men

each would readily turn out in this country; by which is meant the

Lordship of Badenoch, from Lochaber to Strathspey, these companys to be

supplied with light arms, accoutrements, and clothing by Government, to

be drilled, separately, two days in the week as near their own homes as

possible, being paid for these days, and not to be called from hence on

any account except in case of invasion, and that we confine our service

to the coast ’twixt Inverness and Aberdeen; and that such services are

not to be expected or demanded but during an invasion or civil commotion

within that district.

These, my lord, are my

ideas on the subject, and I take them from my knowledge of the state of

the country and the sentiments of the people. But should your Grace

think of a better plan, or one more conciliating to the minds of the

people, I shall readily and chearfully concur with you, as far as I can,

in any way your Grace may think most effectual for thwarting the views

of our inveterate enemy against our Gracious Sovereign, our Country and

happy constitution.

The [Volunteer] Company,

tho’ drilled separately for the convenience of the inhabitants, will

march and act in a body, should there be occasion for it.

Æneas Mackintosh, writing

on March 16 from London, whither he had taken his wife for the benefit

of her health, was also dubious.

I feel myself at this

distance—without any communication with the other Gentlemen, heads of

families—incapable of giving a decided opinion. Although I have every

inclination to give effect to any Plan that may be suggested . . . yet,

upon the first idea being suggested, it appears to me that from the

great drain the country has already sustained, it will be almost

impossible to raise the body of men proposed, if they are liable to be

sent to England, but especially to Ireland. And, I conceive, I need not

remind your Grace how little influence the chieftains retain at this day

in comparison of what it was half a century ago. Whatever arrangement it

may ultimately be decided to carry into effect for the real internal

defence of Scotland, your Grace may rely its having my best wishes, and

any personal aid in my power shall not be wanting.

A very different tone was

adopted by Cameron of Lochiel, who wrote a significantly rude letter

from Glasgow, by return of post, March 6: —

[I] am clearly of opinion

that every exertion in the present time must be used by those who have

power and interest in the Highlands; and, as far as relates to myself, I

am ready to come forward not only on account of the situation of my

country, but the great satisfaction I shall feel at leaving your Grace’s

regiment [the Northern Fencibles], which I am perfectly dissatisfied

[with], and am not the only one; I am convinced if all the circumstances

were known to you, you would not be surprised.

In reply to your Grace’s

question whether the men would go to Ireland, I don’t know what they

would do, They have already been asked by Lieutenant-Colonel Woodford

[the Duke’s brother-in-law who commanded the Fencibles] and refused him.

Nothing, my Lord Duke, would have induced me to be in this corps but the

idea of affording my neighbour, the Duke of Gordon, every assistance in

my power, which, I hope, will always be the case. Therefore, should it

so happen that

I am called on by your

Grace to come forward according to the Plan proposed, I shall expect

that same friendly assistance from you by which each of us ought at all

times to be governed.

Whatever the Duke may

have thought, his uncle, Lord Adam Gordon, then Commander of the Forces

in Scotland, had summed up the Celt in his own mind, for he wrote,

August 5, 1795, giving as one of his reasons for opposing the proposal

to commute in part the loaf of wheaten flour to oatmeal “ the suspicious

nature of the Highlanders ” and their jealousy.

Perhaps it was to this

Grampian Brigade proposal that, according to a letter from Lord Fife to

his Deputies, November 9, 1803, the Lord Lieutenancy of Banffshire had

proposed in March, 1797 (.H.O. 50: 59), to fix alarm signals along the

coast to announce the approach of an enemy by erecting flagstaffs at

Trouphead, Melrose Head, the Hill of Redhyth, Logiehead and Portknockie

Head. The alarm signal for calling out the people in the more inland

parts of the county was to be by the ringing of the church bells, “

which were directed to be rung at funerals and on other occasions in

knells only; but when used as a signal to be rung in loud peals.” But

this idea, like the Brigade itself, melted away, for, the alarm “ having

subsided, the only signal post that was ever erected in consequence of

the resolutions was one on Trouphead, put up by Mr. Garden of Troup,”

who about the same time built a fort at his own expense {H.O. 50 : 94).

Although the raising of

the Gordons showed that the personal equation was still a factor in

territorial soldiering, the reception of the Grampian Brigade scheme

proved that the wholesale raising of Highland regiments was played out.

Indeed, for that matter, the system of I entrusting the organisation of

troops to private individuals was coming to an end—only two Highland

regiments were raised after this date— and the task was transferred to

the local authorities, equipped with the compulsive machinery of the

ballot. It was not merely that the financial resources of individuals

were becoming unequal to the strain, but the need for men was increasing

at an enormous rate and no one could see the end of it. So the State,

which had been so chary of entrusting the task of raising troops to

Corporations in Scotland, was at last driven , to that expedient.

The Militia.

So great had the strain

become that in February, 1797, the Bank of England was compelled to

suspend cash payments. In the same month, a French fleet bore down on

Wales, and in May a mutiny broke out in the Navy at the Nore. True,

Jervis had defeated the Spaniards at Cape St. Vincent, February 14, and

in October, Duncan was to defeat the Dutch at Camperdown; but the year

opened in panic, and part, of that panic resulted in the extension on

July 19, 1797, of the Militia Act (37 Geo. III. cap. 103) to Scotland.

The measure involved the

most serious aspect that soldiering had yet presented, with the

exception of the Comprehending Act of 1778. It approximated the

conditions of Territorial soldiering as we know it to-day in point of

the administrative body,, the Lords Lieutenant, entrusted with raising

it, though by introducing the ballot—which differentiated the Militia

from the Fencibles—it relied on a new machinery.

Mr. Fortescue says that

in Scotland the Militia had been unknown until 1797; but this is not

quite correct. There had been a sort of a Militia since September 23,

1663—Mr. Andrew Ross traces its tangled history minutely in the Military

History of Perthshire (i., 104-124)—when a force of 20,000 Foot and

2,000 Horse was raised. In October, 1678, it was reduced to one fourth;

but even at that, a “Method of turning the Militia of Scotland into a

Standing Army,” was advocated in a pamphlet of 1680 (in the British

Museum). The measure of 1797 differed considerably from this early

Militia, though, curiously enough, it authorised the raising of a force

only a little larger than the 1678 Militia.

England had been equipped

with a Militia in 1757 by an Act, which provided for passing the entire

manhood of the nation through the force by ballot in terms of three

years, though it was not strictly enforced and lost much of its value.

Attempts to extend the measure to Scotland were made in 1760, 1776, 1782