|

Curiosities of the census—Quaint characters—The Bohemians of

the East — Mendicant friars—Actors and jugglers—The Story Teller—"After a

wary day"—A visitor in camp—His appearance—His receptii in—The gaping circle

of listeners—The story—"Petumber and Mahaboobun"— The story of their love—A

rival- —Plot and counterplot—The drama develops—Petumber's sudden

return—Confusion of the wicked plotter— Jealousy—Wifely fidelity—The

darkened bath chamber—Assumption of a strange character—The furious

sandal—Crack!—"T mg-ng-ng!" —Acting up to his character—"Ulug-glug-glng!" —

Another good story—"The Brahmin and the Bunneah"--Sanctity and pretensions

of the Brahmins—Their pow er on the wane—Progress of mi idem thought—An

enlightened Hindoo on the decadence of priestcraft— Bentlicence of British

rule.

It is

a trite observation that "one half the world does not know how the other

half live," and certainly it is very applicable in regard to many of the

modes of livelihood practised in what the poet calls the "gorgeous East." To

the student of human nature, or to a contemplative philosopher, the mere

nomenclature of callings in the Indian census would give rise to many

curious speculations.

There is, for instance, the Haddick, or

Bone-setter, corresponding to our veterinary

surgeon, but with this difference, that the Indian bone-setter relies

chiefly on the efficacy of certain mantras or

charms, and curious medicaments which have been handed down to him through a

long series of generations, and which are supposed to possess some, occult

virtue, which, when applied under certain conditions which are rigidly

prescribed by tradition, -will effect a cure. Matrimonial agents are quite

common. Public scriveners, or writers of correspondence for love-sick swains

and modest maidens, may be found in every bazaar.

Of course the snake-charmer is a character which is never by

any chance left out of any book treating of the East. Professional

witch-finders—Ojahs, as

they are called—are also common to every village community, although to

English readers they recall a state of things now happily passed away from

our history.

Byragees, jogees, fakirs, the

whole fraternity, that is, of mendicant monks, hare-brained religions

enthusiasts, begging friars, and transcendental nostrum-mongers, come across

your path in every direction, and number frequently among their ranks some

of the veriest scoundrels in all the Eastern world, who find the garb of the

religious anchorite a convenient cloak to cover designs of the deepest

rascality.

Even amongst these wandering devotees there are numberless

orders and sub-sections, all of whom have well-defined and specific

functions.

Some are known by marks peculiar to the worship of certain

gods and goddesses emblazoned on some prominent part of their

persons—breast, forehead, arms, &c.,

&c.

Many of these wandering mendicants doubtless belong to

organised gangs, affiliated to each other by passwords and signs.

Put in all large aggregations of humanity in the East they

are sure to catch the eye by reason of their wild outlandish look, their

strange manners or extravagant dress, or some distinctive difference winch

separates them from the common herd.

Then there is the counterpart of the old Roman augur or

soothsayer, one of whom is attached to every menage of

any great importance in an Indian province.

There are beings like the old witch of Endor, who profess

to be able "to summon spirits from the vasty deep," and whose

services are more often called into requisition than the casual observer

might imagine.

There is the Master of Ceremonies, who will take charge of

any feast or merry-making you may wish to give to your retainers or friends.

There is the Bam

Boopeah, i.e.

literally, the man of twelve changes, who will masquerade for

you or your guests in twelve or more guises. He will assume all sorts of

characters: make himself, by a Protean twist of countenance, or readjustment

of dress, a lady of fashion, a woman of low degree, a hireling dancer, a

policeman, a planter, an angel or a demon, just as may suit the whim of the

actor, or the requirements of the audience.

Then there is the professional well-sinker, who does nothing

but sink wells, diving down in the water like a seal or an otter, scooping

out the sand or soil from beneath the massive wooden plates from which the

superincumbent girth of the well is made, thus allowing it to sink by slow

degrees.

There is the bear leader, with his muzzled great brown bear

from the mountain districts, trained to dance for the delectation of the

village youngsters. There is the professional hawker—not the pedlar who

peddles wares as with us "Western nations, but the man who hawks—who trains

the gerfalcon and the kestrel, and who is in fact the modern prototype of

the old falconer of mediaival story.

The dyer, the potter, the weaver, the Nooneah,

or saltpetre maker, the caster of nets, the weaver of the same, the mender

of ditto, the village barber, the man who pares your nails, the professor of

heraldry who will write you out a genealogy suitable to your circumstances

ami varying in splendour according to the amount of our remuneration, are of

course common occupations, and such as might be expected.

All these, and numberless other castes and subdivisions of

castes, ply their busy vocations in the populous East, and are all

recognised under the iron thraldom of that curious caste system which is at

once the wonder and reproach, the shackle and the salvation, according as it

is looked at by different minds, of the marvellous social cosmogony of the

Hindoo world. But among all the multifarious occupations which come under

the purview of an observant "dweller in tents " in an Indian district, none

appeal more quickly to a man of keen observation than the numerous classes

who make their livelihood (often very precarious) by ministering to the

amusement of the people.

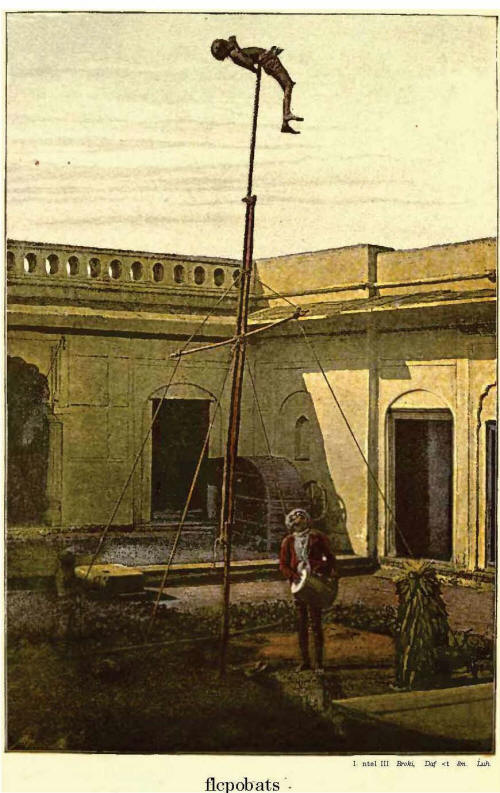

The musicians, the astrologers, the wizards, the enchanters,

the quacks, the acrobats, the bear leaders, the prophets and soothsayers,

the dancers and posture-makers, the snake-charmers, sword-swallowers,

fire-eaters, bards, improvisatores, reciters of ancient legends, the

singers, and the thousand-and-one Bohemians, who drift about in the by-wash

of the great surging flood of humanity that rolls ceaselessly around the

dweller in the East—all these appeal at once to your sense of the

incongruous, to your sense of the picturesque, and being so utterly

different from anything we have in our conventional Western civilisation,

they challenge the attention, and attract the inquiry of the observer at

once. Whole chapters could be written describing their peculiarities,

whimsical instances connected with the pursuit of their vocations; and,

indeed, many a time in my lonely life in India I have been under a deep debt

of gratitude to many a one of these poor wandering performers, who have

wooed me out of sad reflections or gloomy meditations by their

mirth-inspiring antics, or their clever impersonations and really marvellous

tricks. Of the jugglers alone, a whole book might be written.

The sleight of hand of the East is incomparably more finished

and artistic, seeing that it is done in most cases with the aid of no

paraphernalia whatever, than anything we are accustomed to in Europe.

But I never remember to have enjoyed a more hearty laugh than

at the recital on one memorable occasion of a most ridiculous story by one

of these wandering professional

raconteurs, and

which I will, with the reader's permission, now endeavour to reproduce.

I cannot

hope to give it with the same drawling mimetic

art, which made it so funny in the narration the first time I heard it; but

as I have never seen it in print, and think it is new to collectors of these

quaint old tales, I venture to give it here.

One night, after a long, weary, hot day's hard work in one of

my Belahie villages, trying to come to some settlement with a lot of

refractory assaviies, who

would neither pay rent nor take advances, and who had subjected my good

temper and patience to a prolonged and severe strain, I had gone out in the

evening to have a shot at some ducks which had been observed by my servants

in the vicinity of a shallow lagoon near my camp. I had found the brutes shy

and wary. I had shot at several snipe and missed everyone, and had got

bogged up to the middle in a quaking miry clinging morass. My gun had been

badly cleaned, and was kicking like a borrowed horse. The fact is,

everything had gone against me. My liver was out of order, I was in a

despondent frame of mind, and—must I confess it?—in a desperately bad

temper.

To add to my troubles, my dakman had not brought my usual

mail from the head factory. I had nothing to read, and, saddest fate of all,

had nothing to drink and was short of tobacco.

I had got back to the tents, bathed, had dinner and lay down

on my camp bed, restless, discontented and weary, but withal in a very

sleepless mood. The dogs were all tied up at some distance away, and had

been fed by the mahter or

sweeper. My servants had finished their evening meal, and with the points of

their chvjjkuns—a

sort of tight boddice— unloosed, were enjoying the otium

cum dignitate of

a well-earned rest, and were chatting together narrating the events of the

day; when suddenly on my irritated nerves there broke the sound of a cheery

persistent voice, trolling the well-known patter, in a sing-song nasal tone,

of one of these professional story-tellers.

My first impulse was to get up and kick the fellow out of the

precincts of the camp.

I felt so thoroughly "hipped" myself, that I seemed to take

it as a personal insult that anybody in such a weary hot night, amid all the

depressing surroundings, should dare to be cheerful.

There must, however, have been some subtle magnetic influence

or spell in the very tones of the fellow's voice; as presently, raising

myself languidly on my elbow, I found myself surveying with some little

interest, through the open sides of the tent, the appearance of the

new-comer.

He was a grizzled, sun-dried, weather-beaten old fellow, clad

in the most tattered raiment possible, having a greasy skull cap on his

head, merry eyes peeping over a network of wrinkles on each cheek, a broken

nose surmounting a gaping cavern of a mouth, in the inner excavations of

which could be seen two or three yellow glimmering stumps, and altogether

the man looked like a good-natured gnome, some such apparition as might have

been expected to have jumped out bodily from a page of Hans Andersen; and

before I well knew whether to forbid his nearer approach or not, he,

seemingly quite oblivious of my presence, passed the door of the tent, and

with an air of easy familiarity, making himself quite at home, squatted down

by the side of my retainers, who were now wide awake, and gave the man all

the hearty welcome due to an old acquaintance, and one who was evidently a

well known character amongst them.

I lay back and watched.

The usual salutations passed. The new-comer, with the

dexterous ease of a man who knows human nature thoroughly well, and as if by

the exercise of some magic art, was presently the recipient of a bit of

native leaf tobacco from this one, a little chunam from

that one, and betel mit from a third, and indeed all seemed anxious to press

something upon him.

My old bearer gravely

took the mouth-piece of his hubble

bubble

from his lips, and offered it to the old fellow, who took two or three

whiffs.

The old Khansammah, or Butler, Mussulman though he was, came

over with Ins attendant, from where they had been lying apart; and tying up

the points of his chupkum as

he advanced, he made the usual grave Mussulman's salutation, and stroking

his beard with the air of one who is expecting to hear some good thing, he

joined the gathering circle.

My syce and "grass

cuts," who

had been busy combing their well-oiled locks and titivating themselves

generally, suspended the operations of their toilet and gathered around.

Even my grave and dignified old raoonshec seemed

to have felt the impulse of some subtle charm, for he too, with one or two

of the village patwarris, or accountants, came up i 1 their reverent

fashion, with their flowing white robes around them, and gave a pleasant nod

of welcome to the merry-looking little dried chip, who seemed so suddenly to

have become the cynosure of all eyes. By this time my mearims had almost

vanished. I had forgotten all about my liver, and I found myself sitting up

on my pallet, with my ears and my senses on the qui

rive, in

the endeavour to find out what was going on.

Through the half-open Khanats, I

could see without being myself perceived.

The servants seemed to fancy that I must be sound asleep, and

after cracking sundry jokes which seemed to put all his audience in a good

humour, a supplicatory chorus went up from every voice, beseeching him to

tell them a story.

Now I cannot hope, as I have said, to reproduce the action,

the gestures, the facial expression, the inimitable drollery of the raconteur.

The man was a horn actor. Two or three times I found myself

heaving with silent laughter, as he illustrated the various points of his

narration. But this was the story—and you must just take it in my halting

imperfect way; and indeed my only object in occupying your time by giving

it, is because I think the whole picture is one peculiarly characteristic of

tent life in an Indian frontier district, and may serve a useful purpose in

bringing strongly before the mental eye of the reader, some presentment of

the living reality of the life we lead in the remote villages of such an

Indian planting district as I have been endeavouring to describe.

The old fellow had a curious habit, when he seemed to be

searching for a word, of making a quaint clicking sound with his tongue,

then lie would cock his head to one side like a magpie. lie would wag his

old noddle, loll Ins tongue out from amid his gleaming stumps, moistening

lis dry lips, leeringly roll his beady twinkling eyes around, winking at his

audience ; shrug his shoulders like a French dancing-master, sway his body

in unison with the incidents of the story ; and altogether seemed to

mesmerize his audience into complete accord with the varying developments of

his plot; and to tell the honest truth, I must confess that I never heard a

story better told, sweeping as the assertion may appear, and J never enjoyed

any narration with a keener relish, than that of this cunning old artist as

he related the following tale. Thus he began:

"There was once in a village, which I will not name, a man

whom I shall call Petumber." I must give it in the following words but

naturally the story loses a great deal of force by the translation.

"Petumber was a great strong soft-hearted fellow, who was the

best runner and the best wrestler, but the kindest-hearted young man in the

village, always willing to help a neighbour in a difficulty."

And here followed a long description of the various kindly

acts Petumber was wont to do to his neighbours.

For instance this was one. An old woman who was shrewdly

suspected of being a witch, had a favourite nanny-goat which had fallen into

a well, and at the risk of his life Petumber had been lowered down, and

rescued the unfortunate beast.

"Well, time went on, and, as will happen to young men,

Petumber fell in love—with whom think ye? Maii.vbooulN, the

loveliest fay of all the village, daughter of a rich freeholder; and being a

finely-made, good-looking young man, having a fair patrimony, numerous cows

and a fair amount of plough bullocks, his suit was looked upon with some

degree of favour by Malraboobun's relations, and he had reason to believe he

was not altogether uninteresting to the fair Maliaboobun herself."

Put there was an Iago in the case.

Of course he was the exact antithesis of Petumber. This rival

was a swarthy, beetled-browed, bandy-legged character, whose name was Bal

Khrishun, and he also had set his affections on the peerless Mahaboobun. In

the wrestling matches in the village arena, things were so equally balanced,

that although Petumber was the stronger of the two, Bal Khrishun knew more

tricks of the ring, and sometimes was able to snatch a dubious victory from

the broad-chested, open-hearted Petumber by cunning and stratagem, but never

by fair and open play.

Of course Bal Khrrishun was painted as a very Machiavelli—a

double-faced, cowardly, chicken-hearted, scheming scoundrel.

Then came a recountal of all the black deeds he had done.

He was a usurer; he was constantly fomenting strife among

parties in the village, and altogether quite up to the usual three-volume

touch as the villain of the piece.

H e

seemed however to have acquired some strange malign ascendency over the

gentle Maliaboobun, by working on her fears and her timid half-confessed

preference for Petumber, inasmuch as he continually let drop veiled threats

and vague hints as to some evil that he could bring over Petumber, and he

skilfully contrived to make the poor girl to some extent put herself in a

false position by his cunning strategy, that she appeared to listen to his

addresses, while in reality she only dissembled, to appease if she might his

malignant nature.

This part of the story was very cleverly worked out, and the

old man managed to bring his hearers, and myself too, to a perfect pitch of

interest as he described how on one occasion Petumber came upon Bal Khrishun

making overtures to his lady love, which she with tears feebly endeavoured

to resist, anil Petumber's righteous indignation being roused at the sight

of Mahahoobun's evident perturbation, he smote his cowardly rival to the

earth, and left him muttering dire threats of revenge.

Subsequently the two young lovers were united in the sacred

bonds of wedlock, and Bal Khrishun registered his vow of vengeance, and

commenced to scheme against the wedded peace of the loving couple.

B y

a series of skilful combinations, by hints and innuendoes and

cunningly-contrived stratagems, he succeeded in making Maliaboobun rather

jealous of her lord.

Then he contrived to beguile Petumber away to a distant part

of the country, on a pretext that a distant relation was at the point of

death, and wished to leave Petumber some money.

Meanwhile a kindly fairy in the shape of the old woman, whose

goat had been rescued from the well, appeared on the scene, and began to

play a hand in the game.

She had not been an unobservant spectator of the duplicity

that was being practised by the wily and unscrupulous, yet cowardly Bal

Khrishun.

Petumber's rascally rival hail in fact arranged to carry off

Maliaboobun vi

et armis.

A litter borne by soxne "lewd fellows of the baser sort," who

were in his pay, and attached to his service, was to be in readiness in the

mango tope, at

a given hour, and under the pretext that Petumber had sustained a severe

accident, and was wishful to see his loved Maliaboobun before he died, she

was to be inveigled into the litter away from her home, under the charge of

the seemingly good Samaritan, the perfidious Bal Khrishum.

The old woman, however, had got an inkling of what was going

on, and intercepting Petumber on his journey, gave him sufficient warning of

the plot that was being hatched against his domestic peace, to make him at

once change his plans and hurry back.

All this was sketched out with infinite art, by the merry old

story-teller, and I had, as I hope my reader has, become quite interested in

the development of the plot.

My group of servants were listening with open mouths. Now and

then they would laugh heartily at some quaint allusion, or some skilful

touch thrown off by the story-teller, and anon they would hold their breath

as the interest of the drama thickened.

And so we come back to the habitation of Petumber, which was,

as Eastern houses go, large and commodious, with several apartments, and

attached to the sleeping-room, one of those cool, retiring resorts, known as

the oJwosoJ

JcJiana, or

bath-room. Around one side of this room were ranged a number of tall, portly

brass water pots or jars, quite such as we have been accustomed to read

about in the good old story of Ali Paba or the Forty Thieves—just such jars

as Ali Paha hid the robbers in, when he scalded them to death with boiling

oil.

Well, the wily Bal Khridiun, dressed in his best, and taking

advantage of Petumber's absence, came up to put his nefarious scheme into

execution. With I suppose a not unnatural coquetry, the fair Maliaboobun,

mindful that this was an old flame of hers, and not wishing to ihe too hard

upon him, met him with the utmost kindness, and this so raised the wicked

desires and vain hopes of the evil-minded Bal Klirishun, that he began to

venture on rather dangerous retrospections and began to press his claims

upon Maliaboobun's regard, with a slightly greater degree of amorous ardour

than was strictly compatible with the relationship winch actually existed

between them.

Just at this critical moment, with his heart full of

conflicting emotions, boiling with indignation at the duplicity and trickery

to which he had so nearly been a victim ; having been fully informed of the

plot that was being hatched against his domestic peace by the treacherous

Bal Khrishun; Petumber came rushing up to the house in a state of pent-up

fury; and Pal Klirishun's coward conscience taking alarm at the sight of the

indignant husband striding towards the house, he exclaimed in accents of

horror-stricken inquietude, "Arrec

Bapre Bap,—Behold

Petumber!! What is to be done ?! I Alas! I am a dead man, and you are a

ruined woman, unless you hide me from the wrath of your incensed husband."

The situation was too critical to allow of calm reflection 01-philosophic

thought.

Maliaboobun, not unnaturally, felt to some extent the

prickings of conscience, and with a woman's natural wish to avoid bloodshed

and strife, acting upon the impulse of the moment, she hurried Bal Klirishun

into the ghoosal

khana, crammed

him down with trembling and hurried fingers among the row of brass pots, and

told him for Heaven's sake to assume the character of a brass pot himself,

as his very life depended upon it, and if he did not want to ruin her

altogether, she would dissemble and find some way of getting him out of this

perplexing predicament. Then with a parting injunction to keep up his

assumed character, and with a very portentous reminder that Petumber would

not hesitate at taking life when once his passions were roused, she left the

cowering, trembling, cowardly rascal in the semi-obscurity of the damp ghoosal

khana, and

hurried out with palpitating heart to meet her incensed lord.

His first word convinced her that concealment was useless,

and that he knew all that had transpired.

With choking accents of jealous rage, he demanded that she

should produce the miscreant who was endeavouring to sap the foundations of

his domestic tranquillity; and she, beseeching him to restrain his

impetuosity, made a clean breast of it, and while heaping every epithet of

womanly scorn on the head of the miserable Bal Khrishun, whose

double-dealing and vile treachery she now clearly saw, she so contrived to

reassure her husband of her fidelity and love, that the first quick mad

current of his wrath was turned aside, and he determined not to take the

life of his rival, but to teach him a lesson which he would not readily

forget.

You must bear in mind that alb this was recounted as an

actual fact.

The story-teller, if I have succeeded in impressing the

reader sufficiently with an estimate of his wonderful skill had now reached

the very climax- of his dramatic art.

The auditors were agape with eager interest and attention.

Being informed by the clinging wife that the hated rival was

even now in the gfamal

khaaa, Petumber

strode to the aperture in the wall leading into the inner darkened room,

swept aside the drapery which depended from the arch, and bending upwards

his brawny leg he took from its place upon his shapely foot the heavy wooden

sandal which he wore (a high-heeled, brass-bound, heavy galbadunec, which

is worn by travellers when going through the jungles. It has a large wooden

stud, which goes between the great toe and the next-one to it, and is very

useful in keeping the wearer's bare foot off the ground in going through

grass or jungle where snakes might he numerous).

With this in his hand, the angry Petumber, peering into the

obscurity, saw the green glare in the eyes of the abject, cowering, and

hated Bal Khrishun.

His teeth were chattering with fright, and knowing that his

very life depended on his remaining undiscovered, he bent all his thoughts

to keep up the assumption of the character of the brass pot, and determined

at all hazards to act as if he really were one.

Of course he was in ignorance that Maliaboobun had already

divulged his secret. He felt, naturally enough, that his very life depended

on his seeming to be for the time a very brass pot, and nothing else. And

here the original conception and intense dry humour of the situation comes

in.

As quick as thought, Petumber, with unerring aim, launched

his heavy sandal straight between the eyes of the luckless Bal Khrishun.

The crack started the blood flowing from his unlucky sconce,

but he, true to his assumed character, responded with a loud, sonorous,

reverberative "Tung!—tung—ng—ng!"— as the sandal rattled on his skull.

Petumber, thinking that he was being mocked, fancying that he

was being made a butt of, and experiencing a redoubled intensity of wrath,

took up the other sandal, and sent it flying after its fellow, propelled

with all the force of his powerful arm, right between the eyes once again of

the hapless Pal Khrishun. This time he could not altogether suppress a

stifled groan; but, shaking with terror, and still true to the character he

had assumed, lie again sang out " Tung—ng—ng—ng!" The wrath of Petumber now

knew no bounds.

Forgetful of prudence and his promise to his wife, and all

else, except to thrash his adversary, he seized a stout bamboo stick which

stood handy against the wall, and rushed upon the prostrate Bal Khrislmn and

with lusty whacks began to belabour his luckless carcase. Still keeping to

his self-imposed character, the hapless Lothario began rolling about,

imitating a brass pot when it is half full of water and overturned upon the

floor.

At every whack "Tung—ng, glug—glug!—tung—ng, glug glug!" came

from his miserable lips, until at length human nature could stand it no

longer; and after having his body whacked and battered, and Ins nose and

face bruised beyond all recognition, he emitted a dismal yell, and rushed

from the house as if all the furies were after him, ami was never again seen

in the village.

There is such a vein of humour pervading the whole story that

I have thought it well to give it at some length. The general idea, I know,

is that the village Hindoo is rather a melancholy, saturnine creature, with

no sense of humour, but any one who has lived as long as I have amongst the

merry residents of the upland districts of Parneah and Bhairgulpore, would

soon know how erroneous an estimate this is of native character.

With this, however, I think we may take our leave of the

hapless Bal Khrishun. and only hope that Petumber and Maliaboobun lived to a

good old age, and saw troops of children growing around them, in peace and

quiet prosperity.

It is only fair to state that I gave the narrator a handsome bucksheesh, and

certainly felt quite indebted to him for one of the pleasantest evenings I

ever remember to have spent in my tent life.

Perhaps it would, not be out of place to conclude this

chapter by another rather good story which illustrates the marvellous way in

which Western ideas are making progress in the minds of the natives.

It is all very well for half-informed critics at a distance

to decry the efforts of missionaries, of schoolmasters, civil servants,

planters and merchants, and of the many institutions which,, under the

fostering beneficence of British rule, are slowly but surely effecting a

real revolution in native modes of life and thought. The influence of

Western civilisation is evident in every department of industry in India.

The very food and clothing of this most interesting and

conservative people is being affected by the introduction of Western

fashions.

All the modern appliances in the arts and sciences are being

rapidly introduced.

Municipal institutions flourish in most of the towns, and the

criminal law is being administered under a penal code, which, for

comprehensiveness and excellence in its provisions, can hardly be excelled

in any part of the civilised world. With all this, however, the contrasts

one meets with in every Indian district are, as I have already observed,

very striking.

Within the sound of the shrill whistle of the locomotive, yon

will find a temple dedicated to some horrible eight-armed idol, or possibly

decorated with the most obscene sculptures, and consecrated to the

procreative forces in nature, within the shelter of whose courtyard deeds of

infamy are perpetrated, incredible almost in their horrible obscenity.

These are the dark shades of Paganism, but happily evidences

are not wanting to show that the bright beams of "the Sun of Righteousness"

are splintering and shivering the gloomy mass of shadow.

Within a few hundred yards of the busy clank of the

engine-room of an indigo factory you may haply find a reputed witch, a

witch-tinder, a wizard, a magician, an astrologer, or one of these strange

and curious castes, a description of which I gave in the opening of this

chapter, and the simple villagers are quite ready still to believe that

through the mantras or

spells of some of these uncanny practitioners, he or she can blight their

crops, destroy their cattle, influence their destiny, cast spells, work

divinations, and "raise the devil generally."

The Brahmins are of course the reputedly holy and sacred

caste.

As among the Levites of old there were different grades, so

are there different binds of Brahmins. There are wandering Brahmins, who

lead a lazy, vagabondish, itinerant life, certain of a meal wherever they

halt for the night, and sure to be made a guest, by virtue of their caste,

at any house where they may sojourn, at any time whenever the whim seizes

them.

Others are attached to various temples, hold and cultivate

the various temple lands, amass wealth from the rich endowments, and, like "Jeshurnn"

of old, "wax fat," although they get too lazy even to " kick." Others again

officiate as fuinily priests, purohits as

they are called.

These get attached to wealthy families, and perform a rule corresponding

exactly to that of a domestic chaplain in a wealthy nobleman's family at

home.

Brahminism under various modifications is no doubt the

religion of the vast mass of Hindoos generally.

The sanctity of the Brahmin, the necessity for his priestly

office in all the duties of life, forms the fundamental basis of the

gigantic system of sacerdotal supremacy which their superior cunning and

organisation have established during the long course of centuries. To refuse

a Brahmin food is to call down condign punishment from the skies. To beat

him is to consign yourself to an eternity of woe; but to spill his blood, or

even to be the remote cause of having his blood spilt, brings down upon your

head eternal wrath, which is shared by all your relations who have preceded

or may come after you, and actually includes even your neighbours in the

evil consequences of such awful impiety. Such is the orthodox faith re Brahmins.

An amusing incident in exemplification of the fact I have

just stated, that Western ideas are beginning to permeate the masses, and an

illustration of "the little leaven that will finally leaven the whole lump"

of Oriental superstition and credulity, occurred not long ago.

One of these oleaginous, self-complacent, peripatetic,

sacerdotal "loafers," on a begging expedition, like a mendicant friar of

old, came one day and set him down at the door of a grain-seller who was

reputed to be wealthy, but was also suspected of being rather heterodox—in

other words a freethinker, and a dissident from the old school of Hindoo

thought.

The lazy, fat Brahmin was determined to test the Bunncalis orthodoxy,

and, sitting down by the door, demanded, with all the haughty imperiousness

of a high-caste Brahmin, some refreshment.

The Bunneah, however,

had determined that he would no longer pander to this constant drain upon

his resources, for he remembered that he had a family to support, and taxes

to pay, and had to work hard himself for his living.

He was not averse to alms-giving in the abstract, and indeed,

as a rule, the better classes of Hindoos are conspicuously benevolent.

So he did not stint Ins charity when a deserving object was

presented to his notice, but he justly thought that this perpetual blackmail

levied by able-bodied but indolent priests, be they Byragee,

Movlvie, or Brahmin, was

but a premium on laziness, and altogether "too much of a good thing."

So that, being in this mood, it was in vain that the Brahmin

clamoured for a meal. The Bunneah, like

John Grundy's wife in the song, "heard as if he heard him not."

Others of the more pious or less enlightened villagers

pressed their presents of food on the clamorous Brahmin, but his obstinacy

and priestly intolerance were now roused, and lie was determined to

vindicate his arrogant pretensions, and break the spirit of the recalcitrant Bunncoth.

So passed the first day—hierarchical statement of right on

the one hand, against modern heterodox defiance on the other.

On the second day the Brahmin, still persistent, but now

really hungry, poured forth all the curses and comminations of his

stock-in-trade upon the Bunneah's devoted

head, accompanying these with mantras, muttered

spells, and open objurgations.

Still obdurate was the Oriental John Knox.

Finding that the Bunneah did

not care so much as he expected for his ban and malison, the chagrined

Brahmin began to lacerate his arms, cutting himself like one of the priests

of Baal, no doubt thinking that the awful consequences resulting from having

the blood of a Brahmin at his door would break the proud spirit of the

grain-dealer, and force him into submission.

N ot

a bit of it.

The hard-hearted Bunneah was

determined to maintain the position which he had taken, and although the

roused and horror-stricken neighbours crowded around him, and piteously

implored him to make his peace, with the Brahmin, and so avert the dire

consequences, so they imagined, of having sacred blood spilt among

them—that, in fact, their unhappy village might not be consigned with all

its inhabitants to dreadful pains and penalties. Still, however, the

undaunted grain-seller turned a deaf ear to their imploring entreaties.

On the third day the oily old priest, now goaded to

desperation, possibly maddened into an excess of Oriental fury—one of those

paroxysms which come upon Easterns in moments of strong excitement—and

thinking, by a bold move—a coup

dc main, as

it were—to terrify the Bunneah into

submission, be, after solemnly abjuring the obstinate heretic by the names

of all the gods, calling down upon him and upon all the villagers the dire

penalties due to one who was guilty of the death of a heaven-descended

Brahmin, made for a deep well that was situated in the courtyard, and (the

proceedings having attracted nearly all the inhabitants), amid

horror-stricken cries from the crowd of onlookers, and agonising wailings

and a thrill of superstitious dread, plunged down sheer into the gloomy

depths of the well.

The pious villagers were paralysed with horror.

The men tore their hair and their garments, the women

screamed and beat their breasts, and every one in horror-stricken accents

shrieked aloud.

Would nothing move the obduracy of this determined old

iconoclast?

Yes; the Bunneah seemed

at last to relent.

His face betrayed conflicting emotions.

He rushed to the well, the excited crowd gazing with intense

interest at his every action.

Bending over the well, in whose humid depths the floating

form of the discomfited priest was dimly discernible, he besought the

Bralmrin not to drown himself.

You can fancy how the heart of the half-submerged

sacerdotalist leaped for joy at having at length, as he exultantly thought,

established the triumph of orthodoxy.

Behold, now, the reward of his persistency had come after all

Ins long fasting, humiliation, and suffering.

Unwinding his long, strong silken puggree, the Bunneah lowers

it slowly down. With trembling eager fingers it is grasped by the Brahmin.

The Bunneah hauls

up the spluttering unfortunate; but when he reached the top of the well,

guess the awful revulsion of feeling, the supreme dumbfouiiderment he must

have felt, as the strong, vigorous fingers of the Bunneah tightened

on his wrists, and deftly tied these with the puggree which

had just served as a draw-rope; and then, amid the outcries and lamentations

of the shrieking crowd, he hauled the half-drowned and wholly crestfallen

Brahmin off to the nearest police station, and charged him under the l'enal

Code with an attempt to commit suicide.

The sequel is short.

Under the Indian Penal Code this offence is visited with a

minimum punishment of two years imprisonment.

As the case was so clear, the full penalty was inflicted.

This did more to break down the absurd pretensions of the

Brahmins in that village than many a long argument could ever have done.

But this is only one of a hundred indirect ways in which

missionary teaching and English example are bearing fruit.

Doubtless the Brahmin reflected in his cell on the mutability

of human affairs, and must have come to the orthodox conclusion that "the

Church was going to the dogs" altogether.

If I might be permitted the obvious reflection, is not this

an expressed idea with sacerdotalists in other latitudes, and with priests

who are not Brahmins?

Take some of our advanced ritualists, for instance, with

their vain equipments and foolish ceremonies, really offering a "stone" to

the people in place of the Bread of Life, giving the " serpent" of priestly

arrogance and pretentiousness instead of the wholesome "fish" of Divine

Truth, and estranging from the Church the sympathies and support of aB those

in the community who, like our bunneah, are

perhaps not the least advanced and intelligent in their ideas. Possibly so.

But on these matters I am old-fashioned.

The moral is perhaps worthy of some little consideration.

Lest some of my readers may think the story of the Brahmin

and the Bunneah overdrawn, and as further illustrative of the change in the

mental attitude of the more progressive and liberal-minded natives towards

their old faith and old caste exactions, let me give an extract or two from

a most interesting book written by Sahib Chunder Bose, of Calcutta, himself

formerly, I believe, a high caste Hindoo, and which is well worth the

perusal of any one who wishes to see "The Hindoos as they are." Indeed, that

is the title of the book, published in 1881. Loudon: Edward Stanford, 55

Charing Cross, and Newman and Co., Calcutta.

At page 108, speaking of Doorga Poojah Festival, the learned

Baboo writes:

"On the third or last day of the Poojah, being the ninth day

of the increase of the moon, the prescribed ritualistic ceremonies having

been performed, the officiating priests make the hoam and dlwjcinanto, a

rite, the meaning of which is to present farewell offerings to the goddess

for one year, adding in a suitable prayer that she will be graciously

pleased to forgive the present shortcomings on the part of her devotees, and

vouchsafe to them her blessings in this world as well as in the world to

come. "This," says the Baboo, "is a very critical time for the priests,

because the finale of

the ceremony involves the important question of their respective gains." He

then shows how the priests—generally three in number—fight among themselves

for the biggest share of the fees, and will not complete the ceremony by

pronouncing the last prayer till the knotty question of the distribution of

fees is satisfactorily settled. He thus proceeds: "It is necessary to add

here that the presents of rupees which the numerous guests offered to the

goddess during the three days of the Poojah, go to swell the fund of the

priest, to which the worshipper of the idol must add a separate sum, without

which this act of merit loses its final reward in a future state. The

devotee must satisfy the cupidity of the priests or run the Ash of

forfeiting divine inerey. "When

the problem is ultimately solved in favour of the officiating priest

who actually makes the Poojah, and sums of money are put into

the hands of the Bralnnins, the last prayer is read. It is not perhaps

generally known," adds the writer, "that the income the Indian ecclesiastics

thus derive from this source supports them for the greater part of the year,

with a little gain in money or kind from the land they own."

At page 155, speaking of the Saraswati Poojah, the following

very suggestive sentences occur: "In every chatoospah, or

school, the Brahmin Pundit and his pupils worship this goddess with

religious strictness. The Pundit, setting up an image, invites all his

patrons, neighbouring friends and acquaintances on this occasion. Every one

who attends must make a present of one or a half rupee to the goddess, and

returns home with

the hollow benediction of the Brahmin." (The

italics are mine.) "To so miserable a strait have the learned Pundits been

reduced of late years, that they anxious!} look forward to the anniversary

of this festival as a small harvest of gain to them as the authoritative

ministers of the goddess. They make from fifty to one hundred rupees a year

by the celebration of this Poojah, which keeps them for six months; should

any of their friends fail to make the usual present to the goddess, they are

sure to demand it as a right." And in a pregnant footnote he adds :

"A gift once made to a Brahmin must be continued from year to

year till the donor dies; in some cases it is tenable from one generation to

another."

At page 187 he says: "If Manu were to visit Bengal now, his

indignation and amazement would know no bounds in witnessing the sacerdotal

class reduced to the humiliating position of a servile, cringing and

mercenary crowd of men. Their original prestige has suffered a total

shipwreck. Generally speaking, a Brahmin of the present day is practically a

Soodra (the most inferior class) of the past age, irretrievably sunt in

honour and dignity. Indeed it was one of the curses of the Vedic period that

to be a Brahmin of the present, Kaliyagu, would

be an impersonation of corruption, baseness and venality."

And he sums up by saying:

"He" (the Brahmin) "can no longer plume-himself on his

religious purity and mental superiority, once so pre-eminently

characteristic of the order. The spread of English education has sounded the

death-knell of his spiritual ascendency. In short, his fate is doomed; he

must bear or must forbear, as seems to him best. The tide of improvement

will continue to roll on uninterruptedly," etc., etc.

So much for Baboo Sahib Chunder Bose, His view is undoubtedly

the correct one in great measure, and little wonder need be felt that the

erstwhile " lordly Brahmin " bitterly hates the white-faced beefeaters from

across the "Black Water," and would hail the day with glad acclaim that

would see the last of our red-coats swept into the river or the sea.

The classes like the Bunneah, however—the trading, industrial

and cultivating classes—do not, I am willing and glad to believe, share in

this dislike of British rule; and after all, these are the people,

the mainstay of any system of government; and our chiefest and proudest

boast as conquerors of India is, that we have consolidated the rule we won

by the sword through the grateful recognition of an

emancipated people, that we seek to do justly by them, and endeavour to

reign in their affections, and govern by their free good will! |