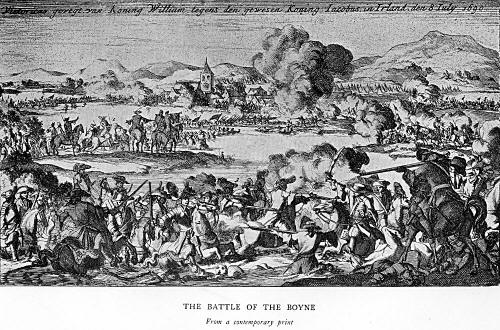

The Vacillation of James—He holds a Council of War,

and finally decides to fight—Nevertheless he sends Six of his Twelve

Field-pieces to Dublin — William's Council of War—Duke Schomberg

overruled—His Chagrin—Tuesday, the 1st of July, 1690—William's Orders

for forcing the Passage of the Boyne—Both James and William neglect to

secure the Bridge of Slane—Count Schomberg forces the Passage at

Rossnaree—Sir Neil O'Neill is slain—The Order of Crossing and how the

Jacobites received William's Forces—Death of Caillemot—Duke Schomberg

plunges into the Fight unarmed—He is killed— Walker of Derry is shot

dead—William heads the Inniskillings—The Jacobites retreat—Flight of

King James to Dublin.

The strongly pronounced contrast between the

characters of the two commanders in the conflict in Ulster was never

more evident than on the eve of battle. Vacillation, which was a marked

characteristic of James, now became painfully and disconcertingly

evident to his generals. He held a council of war, at which it was again

recommended to retreat to the Shannon, and gain time by protracting the

war, rather than risk all upon one contest; and James, feeling himself

to be far from master of his fate or captain of his soul, was perturbed

by conflicting opinions, he himself being much in favour of a project

which had originated with his French allies. It was known that the

French fleet was on the English coast—in fact, on this very day (June

the 30th) it had defeated the united English and Dutch squadrons off

Beachy Head— and that Sir Cloudesley Shovel, with the squadron of

men-of-war which had attended William on his passage, had

received orders to join the Earl of Torrington. The English transports

in Carrickfergus Bay, on which William's army depended for provisions

and stores, were thus left unprotected, and it was proposed to send ten

small frigates and twelve privateers, who had accompanied the French

troops, under Lauzun, and were still at Waterford, to destroy them. A

defeat such as this, it was considered, would disconcert the forces of

William, and, by leaving them dependent on the country through which

they marched, would soon demoralize them to such an extent that a

protracted campaign must inevitably prove a failure. These

considerations, however, gave way before the fact that they were now

face to face with the foe, and it was too late to retreat. Then,

remembering the strength of their position, the Jacobite generals

resolved to await the morrow and the morrow's deeds.

Not so James, who by his lack of determination and

his hesitancy appeared to be resolved to destroy any hope of success

which his army cherished. One moment he decided on a general retreat,

and for that purpose ordered the camp to be raised; but the next minute

he altered his plan, and, sending off the baggage and six of his twelve

field-pieces to Dublin, he apparently made up his mind to risk a battle.

The removal of the baggage was no doubt a good preparation for an

orderly retreat, but it was also a plain intimation to the army that a

retreat was in contemplation; otherwise the reduction of the artillery

must be considered a fatal diminution of strength. James indeed seems to

have thought of nothing so much as means whereby to keep open a passage

in the rear; and all his anxiety appears to have been lest William's

forces should by a flank movement cut off his retreat to the south,

where he had already privately made preparations for his flight to

France. It is evident, also, that he resolved to place himself in such a

position during the battle that he would be one of the first to see on

which side fortune turned, so that in case of defeat he might with ease

make good his escape. Still, with such apprehensions, it is strange how

difficult it proved to persuade him to take any precautions for the

defence of the fords up the river; for late on the eve of the battle he

could only be induced with much difficulty to send Sir Neil O'Neill with

his regiment of dragoons to defend the Pass of Rossnaree, about four

miles from the Jacobite camp towards Slane.

William also called a council of war, at nine o'clock

in the evening, not to take the advice of his officers, but to convey to

them the fact that he had resolved to force the passage of the river

next morning. Rendered impatient by news he had received of political

intrigues in England, and apprehensive, from reports that had reached

him from the Jacobite camp, that James would retreat, he would not

listen to Schomberg's urgent advice against an enterprise that appeared

to be very hazardous. Determined that his plans should not be known, and

suspicious of the fidelity of some of his officers, he merely announced

that he would send to the tent of each officer that night his particular

orders. Schomberg, who appears to have been ignorant of the motives of

William, is said, when the order of battle was delivered to him, to have

remarked that he was more used to giving such orders than to receiving

them. The old general is also said to have been much annoyed at the

overruling of his advice to detach a portion of the army to secure the

bridge of Slane, so as to turn the flank of the Jacobites and cut them

off from the Pass of Duleek. At midnight William made a final inspection

of his forces by torchlight, and issued his final orders, which included

directions that "every soldier was to put a green bough in his hat. The

baggage and great coats were to be left under a guard. The word was

'Westminster'."

The morning of Tuesday, the 1st of July, 1690, dawned

bright and unclouded on the hostile camps. The first movement in the

Williamite army was the march, at sunrise, of a division of 10,000

picked men. William's orders were that the river should be crossed in

three places. The right wing, commanded by Count Meinhardt Schomberg

(one of the Duke's sons), assisted by Lieutenant-General Douglas and

Lord Portland, was to pass at some fords near the bridge of Slane to

turn the left flank of the Jacobite army. The centre, consisting chiefly

of infantry, and commanded by the Duke of Schomberg, was to pass at the

fords in front of the Jacobite camp at Oldbridge, where had been

collected all James's foot, dragoons, and horse, with the sole exception

of Sarsfield's regiment. The left wing, composed exclusively of cavalry,

and led by King William in person, was to pass at a ford not far above

Drogheda, and flank their foes whilst they were engaged.

James had been prepared for the movement of William's

right wing the night before, and he now saw his fatal error in rejecting

the advice of his officers to provide against it. He hastily ordered the

whole of his left wing, which included Lauzun's French division, with

part of his centre, and his six remaining field-pieces, to proceed with

all possible expedition to oppose the flanking division; but it was too

late to obstruct their passage. The troops under Meinhardt Schomberg

marched more rapidly, and the cavalry forced the passage of the river at

Rossnaree, which was gallantly defended by Sir Neil O'Neill, who lost

seventy of his men and was himself mortally wounded. Portland's infantry

and the artillery crossed at Slane, where the bridge had been broken but

the river was fordable. Their progress was at first arrested by a

morass; but finding, on trial, that though difficult it was not

impossible to pass, the infantry marched into it, while the artillery

went round by a narrow tract of firm ground at the back of the marshy

portion. The Jacobites, astonished, turned and fled, while their

opponents, unacquainted with the nature of the ground, advanced

stolidly, though slowly and floundering at every step. The cavalry moved

more rapidly, and drove before them, with slaughter, all who offered any

opposition to their progress.

It was now nearly ten o'clock, and William, having

heard that Count Schomberg had succeeded in crossing, ordered the

advanced body of his centre to pass the fords. This was composed of the

Dutch, the Brandenburghers, the Huguenots, and the Inniskillings.

Solme's Blues were the first to move. They advanced with drums beating

to the brink of the Boyne, and, marching ten abreast, entered the stream

at the highest ford opposite Oldbridge. So shallow was the water here

that the drummers only required to raise the drums to their knees. The

Londonderry and Enniskillen horse followed, and at their left the

Huguenots entered, led by Caillemot, brother of the Marquis de Ruvigny.

The English infantry came next, under Sir John Hanmer and the Count

Nassau; lower down were the Danes; and at the fifth ford, which was

considerably nearer to Drogheda, and at which the water was deeper than

at any of the former, William himself crossed with the cavalry of his

left wing. Thus was the Boyne, for nearly a mile of its course, filled

with thousands of armed men struggling to gain the opposite bank, which

bristled with pikes and bayonets. A fortification had been made by

French engineers out of the hedges and buildings, and a breastwork had

been thrown up close to the water-side. Tyrconnell was there, and under

him were Richard Hamilton and the Earl of Antrim.

When the Dutch reached the middle of the river a

heavy fire was opened upon them from the breastworks, houses, and

hedges, but was ill-directed, and therefore without much effect. As fast

as they reached the opposite bank they formed and attacked the Jacobites,

who fled from their first defences in the utmost disorder; but as their

assailants advanced, fresh troops sprang up from the hedges and ridges

behind, and, multiplied to the eye by the manner in which they were

disposed, presented a far more formidable appearance than was

anticipated. Five battalions bore down upon the Dutch, but they were

repulsed. The Jacobite horse were next directed against them, but with

no better success, and the Dutch had repulsed two attacks when the

Inniskillings and Huguenots arrived to assist them, and drove back with

great slaughter a third body of horse.

General Richard Hamilton, who acted throughout the

day with marked bravery, and who commanded the Jacobite horse, enraged

at the pusillanimity of the foot, distributed brandy among his men, and

then led them furiously against the advancing troops, who had now

cleared most of the hedges and were ready to form on the unbroken

ground. At the same time the French infantry rose suddenly from behind

the low hills in the rear, and advanced in good order to support

Hamilton's charge. The English centre, confounded at this sudden attack,

stood for a moment irresolute. A squadron of Danes, attacked by a part

of Hamilton's horse, turned in mid-stream, being followed into the water

by their pursuers. The latter then threw themselves upon the Huguenots

under Caillemot, who, being unsupported, and having no pikes to

withstand the charge, were broken, and their gallant leader ridden down

and mortally wounded. Four of his men carried him back across the ford

to his tent. As he was borne away he urged on his men, crying to them in

French: "To glory, my lads, to glory!"

The Jacobite foot left to defend the ford were, in

point of numbers, utterly inadequate, and it is stated that very few of

them had muskets, their principal arm being the pike. At the onset they

saw themselves unsupported, and they had already suffered severely

before the horse came to sustain them, so that under the circumstances

they scarcely deserve the epithet of a "mob of cow stealers" which

Macaulay bestows upon them. Tyrconnell, who held the chief command in

the absence of James, behaved like a gallant soldier; but it would have

required more consummate generalship than he possessed to retrieve the

fortune of the day. The Jacobite cavalry fought with much valour, the

only exceptions being Clare's and Dungan's dragoons; and, the latter

having lost their able young commander by a cannon-shot at the

commencement of the action, their discouragement was to a certain extent

excusable. It was also unfortunate for the Jacobites that Sarsfield's

horse accompanied King James as his body-guard, and were thus prevented

from taking any part in the action.

Schomberg, who watched the struggle from the northern

bank, perceiving the distress of the centre, and learning of the death

of Caillemot, now plunged into the river with the impetuosity of a young

man, disdaining to don his cuirass, which was pressed upon him by those

near him. Without defensive armour he rode through the river to rally

the Huguenots, whom the fall of Caillemot had dismayed. "Come on!" he

cried in French to the refugees; "there are your persecutors!" pointing

with his sword as he spoke to the French squadrons serving under King

James. These were his last words. At this moment a troop of Jacobite

horse dashed furiously in his direction. He was surrounded and killed,

receiving two sabre wounds on the head and a carbine bullet in the neck.

About the same time Walker, the gallant Governor of Londonderry, to whom

William had just given the See of that city, was also shot dead. The

King, who believed that clergymen should confine themselves to such

spiritual weapons as the sword of faith and the breastplate of

righteousness, when informed that "the Bishop of Derry has been killed

by a shot at the ford", contented himself by asking: " What took him

there?" The firing had now continued incessantly for about an hour, but

it began to slacken amid the general disorder; the tide had begun to run

very fast and the passage of the Boyne was becoming more difficult. The

battle raged with great fury along the southern shore of the river, the

contest being well sustained by both parties; but the Jacobite horse of

one wing had to resist unsupported the advance of all the horse and foot

of William's left and centre, to which task it was entirely unequal, and

they retired, fighting obstinately.

The day was decided by the approach of William, who

did not cross the river until late in the action. The advance of the

cavalry had been retarded by the unexpected difficulties experienced in

crossing, owing to the bottom of the river which was extremely soft,

indeed so much so that William's own charger was forced to swim, and was

very nearly lost, the King being obliged to dismount and be carried over

by his attendants. As soon as he was on firm ground he took his sword in

his left hand—his right it will be remembered had been wounded the day

before—and led his men to the place where the fight was hottest. They

were charged by the Jacobite cavalry with such violence that they were

driven back. At this moment William, in the midst of the tumult, rode up

to the Inniskillings and cried: "What will you do for me?" He was not

immediately recognized, and one dragoon, in the heat of action,

mistaking the King's identity, was about to shoot him, when William

calmly turned the weapon aside, with the query: "Do you not know your

friends?" "It is His Majesty!" cried the Colonel, and the Inniskillings

received the announcement with a shout of delight. "Gentlemen," said

William, "you shall be my guards to-day. I have heard much of you. Let

me see something of you." At length the Jacobite infantry gave way on

every side. Hamilton again placed himself at the head of the cavalry and

made a desperate attempt to retrieve the future of the day; but though

they made a momentary impression they were soon routed, and he was

himself severely wounded and taken prisoner.

Meinhardt Schomberg had in the meanwhile been

clearing the difficult grounds which had retarded his march, and was now

engaged in a pursuit of the troops opposed to him towards Duleek. Long

before this an aide-de-camp brought news to James that William's forces

had made good their passage at Oldbridge, whereupon the hapless monarch

ordered Lauzun to march in a parallel direction with that of Douglas and

Count Schomberg towards Duleek, which place he reached before the flying

throng of the Jacobite foot. Tyrconnell came up next; and now for the

first time the French infantry rendered good service to their side by

their admirable discipline, preserving their own order and cooperating

with the Jacobite cavalry in covering the retreat. Berwick's horse was

the last to cross the narrow pass of Duleek, with the forces of William

close in the rear; but beyond the defile the Jacobites rallied. Five of

the six field-pieces which James had taken with him in the morning

towards Slane were still available; the sixth had stuck in a bog. At the

deep defile of Naul the last stand was made. It was now nine o'clock;

the fighting had lasted since ten o'clock in the forenoon. The Jacobites

drew up in good order and presented a determined front; seeing which it

was deemed impolitic for so small a force to attack them, and the order

was given for a return to Duleek.

Thus ended the memorable battle of the Boyne, in

which William is said to have lost not more than 500 men, while the loss

of the Jacobites has been variously estimated at from 1500 to 2000,

including Lords Dungan and Carlingford and Sir Neil O'Neill. To William

the day was embittered by the loss of Schomberg and Caillemot. James

fled precipitately to Dublin. William's army lay on their arms at Duleek.

The King's coach had been brought over, and he slept in it surrounded by

his soldiers.