|

“Prolific May, whose everburning lamp

Through dang’rous seas, between approaching coasts,

‘Mid hidden scares, unseen, and broken rocks,

In pitch of night, directs the doubtful path

Of fearless mariner.’

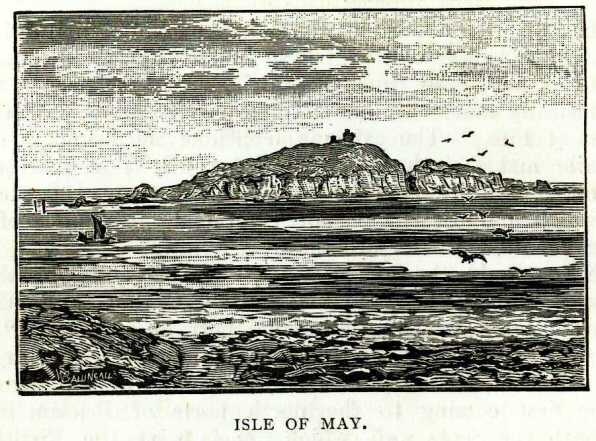

Extent.—This Guide would be incomplete if it did not contain a

chapter on the Isle of May—although its nearest point is five miles from the

Harbour of Crail—since it is historically and otherwise so intimately

associated with the East of Fife. The extreme length of the island is only a

mile and a sixth, its greatest breadth is a quarter of a mile, and it

contains little more than 140 acres, of which a tenth is fore-shore; yet

many memories of no common kind cluster around it.

Name.—In the first part of his History of Fife, Sibbald says that the

May “in the ancient Gothic signifieth a green island;“ but, in the second

part, he says that “the word Maia seemeth to have some affinity with

Moeotoe, the name of some tribes of the Picts, who at the Romans their first

coming to the north parts of Britain, lived besouth the Scots wall, which

ran betwixt the Firths of Forth and Clyde, as Dion, in the life of Severus

telleth us; and it is very probable that a colony of these people first took

possession of it, and gave it the name Maia.”

The Earliest Reference to the Isle of May is found in a fragment of

the Life of Kentigern. It is there stated that the saint’s mother, Thaney,

was, by the order of her father, King Leudonus, placed into a boat made of

hides, carried out into deep water beyond the Isle of May, and there

abandoned. She was put in the coracle at “the mouth of a river which is

called Aberlessic [now Aberlady], that is, the Mouth of Stench, for at that

time there was such a quantity of fish caught there that it was a fatigue to

men to carry off the multitude of fish cast from the boats upon the sand,

and so great putrefaction arose from the fish which were left on the shore,

where the sand was bound together with blood, that a smell of detestable

nature used to drive away quickly those who approached the place.” But the

fish all followed Thaney and her boat to the place where she was abandoned,

and there they remained—so, at least, Kentigern’s unknown biographer says.

He adds that “from that time until now the fish are found there in such

great abundance, that from every shore of the sea, from England, Scotland,

and even from Belgium and France, very many fishermen come for the sake of

fishing, all of whom the Isle of May conveniently accomodateth in her

ports.”

Adrian.—The next notice of the May is by Wyntoun, who, in his

Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland, says that :—

“Saynt Adriane wyth hys cumpany

Come off the land of Hyrkany,

And arrywyd in to Fyffe,

Quhare that thai chesyd to led thar lyff.

At the king than askyd thai

Leve to preche the Crystyn fay.

That he grantyd wyth gud will,

And thaire lykyng to fuiflule,

And (leif) to duehl in to his land,

Quhare thai couth chea it mayst plesand.

Than Adriane wyth hys cumpany

Togydder come tyl Caplawchy.

Thare sum in to the lie off May

Chesyd to byde to thare enday.

And sum off thame chesyd be northe

In steddis sere the Wattyr off Forth.”

Alas ! poor Adrian and his company were not allowed to preach the Christian

faith in peace. The heathen Danes quickly slew the leader and many of his

followers. Wyntoun thus describes the tragedy

“Hwb, Haldane, and Hyngare

Off Denmark this tyme cummyn ware

In Scotland wyth gret multitude,

And wyth thare powere it oure-ghude.

In hethynnes all lyvyd thai;

And in dispyte off Crystyn fay

In to the land thai siwe mony,

And put to dede by martyry.

And apon Haly Thurysday

Saynt Adriane thai siwe in May,

Wyth mony off hys cumpany:

In to that haly Isle thai ly.”

In some of the lists of the Bishops of St Andrews, Adrian is put as the

first. His martyrdom is said to have taken place in 875; and Thaney’s

adventure fully three centuries and a-half earlier.

Monastery Founded.—It was probably because of its association with

Adrian, that King David the First founded a monastery on the Isle of May,

“before the middle of the twelfth century, which he forthwith granted to the

Benedictine Abbey of Reading in Berkshire, recently founded by his

brother-in-law, Henry Beauclerc.” The monks of Reading were bound by the

charter of donation to maintain nine priests on the May to pray for David’s

soul, and the souls of his predecessors and successors, the Kings of

Scotland. Not long afterwards, Swein Asleif wasted the island and plundered

the monastery; but it was greatly enriched by David, Malcolm the Maiden,

William the Lion, and Alexander the Second. Among other gifts, David granted

to the Abbey of Reading the viii of Rindaigros, occupying the angle where

the Tay is joined by the Earn, and there a religious house was also

established. Malcolm the Fourth commanded all good men who fished round the

May, to pay their tithes to the monks as in the time of his grandfather.

William the Lion prohibited all from fishing in their waters without their

leave; and “granted them fourpence from all ships having four hawsers coming

to the ports of Pittenweem and Anstruther for the sake of fishing or

selling fish, and in like manner .of boats with fixed helms.”

Recovered from the English. —For fully a century, the monks of

Reading retained possession of the Priory of May. But it is said that

Alexander the Third was anxious to recover the island from the hands of the

English aliens, as they could use it for spying out the weak parts of the

country. And so, Bishop Wishart of St Andrews bought it, in or about 1269,

from one of the Abbots of Reading, and paid to him 1100 merks of the price.

One of the Abbot’s successors, however, being dissatisfied with the

bargain, tried to overturn it. He sent two representatives to Baliol’s

Parliament at Scone, in 1292, to claim possession of the Priory, or to get

the rest of the price. The Bishop of St Andrews appealed the case to Rome,

and the two attornies appealed to King Edward as Lord Superior of Scotland.

That King, ever on the watch in his designs on the independence of Scotland,

cited Baliol four different times to appear before him. The dispute, with

others of more importance, was finally settled at Bannockburn. All the

rights to the Priory of May were transferred to the Canons of St Andrews in

1318. “In this deed,” says Dr John Stuart, in his Preface to the Records of

the Priory of the Isle of May, “we find the Priory styled as that of ‘May

and Pittenweem;’ and in later documents it is frequently designated as that

of ‘Pittenweem, otherwise Isle of May,’ or ‘Isle of St Adrian of May,’ and

at times as that of Pittenweem alone. This has led several writers to

suppose that originally there were two distinct priories, one of May and

another of Pittenweem, and that the latter was dedicated to the Blessed

Virgin. The explanation seems to be, that the monks of May had, from the

first, erected an establishment of some sort on their manor of Pittenweem,

on the mainland of Fife, which, after the Priory was des-severed from the

house of Reading and annexed to that of St Andrews, became their chief seat,

and that thereafter the monastery on the island was deserted in favour of

Pittenweem, which was less exposed to the incursions of the English, nearer

to their superior house at St Andrews, and could he reached without the

necessity of a precarious passage by sea.” Mr David Cook, in Fifiana,

contests Dr Stuart’s opinion; but, it seems to me, that he has done so

unsuccessfully. The outline of the later history of the Priory is continued

under Pittenweem.

Alienation.—In 1549, the Prior of Pittenweem feued the Isle of May to

Patrick Learmonth of Dairsie, Provost of St Andrews; and the deed of

conveyance, containing an epitome of the history of the Priory, has been

printed by Dr Stuart. “The Prior alleges as motives for the alienation of

the island, its insular situation, at a distance from himself, yielding

little or no revenue, and that on the outbreak of hostilities the place was

wont to be seized by the enemy, and was thus rendered a sterile and useless

possession of the monastery. He therefore granted the island—which he

describes as now waste, and spoiled by rabbits from which the principal

revenue used to accrue, but of which the warrens were now completely

destroyed, and the place ruined by the English—together with the right of

patronage of the church on the island, and of presenting a chaplain to

continue divine service therein, out of reverence for the relics and

sepulchres of the saints resting in the island, and for the reception of

pilgrims and their oblations, according to the use of old times, and even

within memory of man.”

Ruins.—The “stately monastery of stone” had been destroyed by the

barbarous English; but a church remained which was resorted to by the

faithful on account of the frequent miracles there wrought. There is still a

fragment of this church. It has been a plain parallelogram measuring inside

barely 32 feet by 15k. The two windows in the west wall show that it dates

from the thirteenth century. Their external tops are each cut out of one

stone, and internally they are arched and enormously splayed. The most

remarkable thing about this chapel is that it stands almost due north and

south. There can be little doubt that it was long preserved “out of

reverence for St Adrian and the other saints there interred.” The

foundations of some of the other buildings can still be traced. The portion

of a stone coffin which still remains may have been Adrian’s, although that

is unlikely enough; but there need be no hesitation, at any rate, in

rejecting the tradition which seeks to prove that a somewhat similar

fragment, preserved at West Anstruther Church, is a portion of this one, by

asserting that it floated over. The chapel has suffered from alteration as

well as from dilapidation. The oven in the bottom of the south window is

modern; but the large press in the west wall, and the circular tower pierced

with shot-holes are pretty old. The latter has evidently been built at some

time for defence.

No trace seems to be left of the chapel of the “Blessed Virgin,” which is

known to have been on the island. There appears also to have been a chapel,

or perhaps more probably an altar, of St Ethernan. Many curious details of

the pilgrimages of James the Fourth to the May are given by Dr Stuart, but

want of space compels me to omit them.

Old

Lighthouse.—The island only remained two years in Learmonth’s

possession, for it was conferred on Balfour of Manquhany in 1551, and seven

years later it was granted to Forret of Fyngask. It afterwards became the

property of Allan Lamont, who sold it to Cunningham of Barns. Alexander

Cunningham is commonly said to have been the first to erect a lighthouse

upon it. “He built there,” says Sibbald, “a tower fourty foot high, vaulted

to the top, and covered with flag-stones, whereon all the year over, there

burns in the night-time a fire of coals, for a light; for which the masters

of ships are obliged to pay for each tun two shillings—that is, twopence

sterling. Sibbald is certainly wrong about the builder of the Lighthouse,

and he is also inaccurate in regard to the dues. In 1641, Parliament

ratified the letters-patent which had been granted, in 1636, to James

Maxwell of Innerweeke, one of His Majesty’s “bed chalmer,” and to John

Cunynghame, of Barnes, for erecting and maintaining a light on the Isle of

May. According to the letters-patent, they had been granted an impost of 2s

Scots on the ton of all native ships and vessels coming within “Dunnoter and

St tobe’s heid,” and 4s Scots on strangers, for “ilko veadge” —i.e., each

voyage. But, in 1639, the “patenteres” being willing to give all reasonable

satisfaction to the Convention of Burghs, the dues were restricted to 1s 6d

Scots per ton for natives, and 3s for strangers; while all “barkes, creires,

and others weschelles,” during the months of May, June, and July, and 15

days of August, and “Northland victuellers,” were to be free of all duty.

The “patenteres” would not suffer by this restriction, as the members of

Convention obliged themselves to cause their neighbours to “make thankful!

payment,” as also to assist in collecting the dues, and to furnish a list of

the “haill shippes” pertaining to their burghs, with the number of “the

tunes of ilke shipe.” The Act of the Convention was also ratified by

Parliament in 1641. And a new charter, which had been granted by the King to

John Cunynghame, of the lands and barony of West Barns, comprehending “the

Tie landes and Isle of Maij,” was ratified by Parliament in 1645, for his

good, true, and thankful service in “bigging and erecting . . . . ane Light

hotis,” and maintaining the light continually. Two years later, Parliament

ordained that the restricted duty should be peaceably uplifted and enjoyed

by John Cuuynghame, who now had the full right of the gift and patent. In

1651, Sir Patrick Myrtoun of Cambo complained that, owing to the loss of

trade, the lights of the May were no benefit to him, although a great part

of his estate was engaged for the same. Ten years afterwards, Parliament

enacted that the restricted duty should be paid to Sir James Halket of

Pitfirren, and Sir David Carmichaell of Balmadie. The island is included in

a charter granted to the Earl of Kellie in 1671 and ratified in 1672. Before

1790 the duty was let at £280 sterling per annum, but in that year it rose

to £960, and in 1800 it was let at £1500. About 380 tons of coal were

consumed every year; but the light, even then, was not satisfactory, as in a

gale it hardly showed except on the leeward side, where it was of least use.

As the event proved, it was also dangerous. In January 1791, the keeper, his

wife, and five children, were suffocated. One child, who was found sucking

the breast of her dead mother, was saved; and the two assistant keepers,

though senseless, were got out alive. The ashes, which had been allowed to

accumulate for more than ten years, reached up to the window of the keeper’s

room; and having been set on fire by live coals falling from the lighthouse,

and the wind blowing the smoke into the windows, and the door below being

shut, the result was inevitable. The two men who escaped declared that a

sulphureous steam was observed to issue from the heap of cinders for several

weeks before the fatal night on which it burst into flames, and therefore it

was supposed by some that there had been a fermentation among the ashes.

Formerly, the families who resided there lived in houses detached from the

tower, and it was now resolved to re-adopt the old plan. In Sibbald’s time

there was “a convenient house with accomodations for a family,” which may

have become ruinous before 1791. Probably this house and the old tower were

built with the stones of the monastery. The architect who planned and built

the tower was drowned in returning to his house, which led to the burning of

several witches who were supposed to have raised that storm. In a

bombastically written book, entitled The Key of the Forth, or Historical

Sketches of the Island of May, the story of the architect and the witches is

spun out to a great length, being made the ground-work of something like a

tragic romance of love. The old tower, which is now used as a look-out by

pilots, still bears over the door the date 1636. As it is supposed to have

been the first lighthouse erected in Scotland, a special interest attaches

to it. Mr Merson states that an earlier light-house existed on the island,

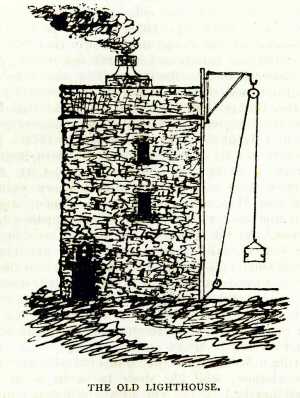

but he gives no authority. The accompanying illustration shows how the coals

were raised. Old

Lighthouse.—The island only remained two years in Learmonth’s

possession, for it was conferred on Balfour of Manquhany in 1551, and seven

years later it was granted to Forret of Fyngask. It afterwards became the

property of Allan Lamont, who sold it to Cunningham of Barns. Alexander

Cunningham is commonly said to have been the first to erect a lighthouse

upon it. “He built there,” says Sibbald, “a tower fourty foot high, vaulted

to the top, and covered with flag-stones, whereon all the year over, there

burns in the night-time a fire of coals, for a light; for which the masters

of ships are obliged to pay for each tun two shillings—that is, twopence

sterling. Sibbald is certainly wrong about the builder of the Lighthouse,

and he is also inaccurate in regard to the dues. In 1641, Parliament

ratified the letters-patent which had been granted, in 1636, to James

Maxwell of Innerweeke, one of His Majesty’s “bed chalmer,” and to John

Cunynghame, of Barnes, for erecting and maintaining a light on the Isle of

May. According to the letters-patent, they had been granted an impost of 2s

Scots on the ton of all native ships and vessels coming within “Dunnoter and

St tobe’s heid,” and 4s Scots on strangers, for “ilko veadge” —i.e., each

voyage. But, in 1639, the “patenteres” being willing to give all reasonable

satisfaction to the Convention of Burghs, the dues were restricted to 1s 6d

Scots per ton for natives, and 3s for strangers; while all “barkes, creires,

and others weschelles,” during the months of May, June, and July, and 15

days of August, and “Northland victuellers,” were to be free of all duty.

The “patenteres” would not suffer by this restriction, as the members of

Convention obliged themselves to cause their neighbours to “make thankful!

payment,” as also to assist in collecting the dues, and to furnish a list of

the “haill shippes” pertaining to their burghs, with the number of “the

tunes of ilke shipe.” The Act of the Convention was also ratified by

Parliament in 1641. And a new charter, which had been granted by the King to

John Cunynghame, of the lands and barony of West Barns, comprehending “the

Tie landes and Isle of Maij,” was ratified by Parliament in 1645, for his

good, true, and thankful service in “bigging and erecting . . . . ane Light

hotis,” and maintaining the light continually. Two years later, Parliament

ordained that the restricted duty should be peaceably uplifted and enjoyed

by John Cuuynghame, who now had the full right of the gift and patent. In

1651, Sir Patrick Myrtoun of Cambo complained that, owing to the loss of

trade, the lights of the May were no benefit to him, although a great part

of his estate was engaged for the same. Ten years afterwards, Parliament

enacted that the restricted duty should be paid to Sir James Halket of

Pitfirren, and Sir David Carmichaell of Balmadie. The island is included in

a charter granted to the Earl of Kellie in 1671 and ratified in 1672. Before

1790 the duty was let at £280 sterling per annum, but in that year it rose

to £960, and in 1800 it was let at £1500. About 380 tons of coal were

consumed every year; but the light, even then, was not satisfactory, as in a

gale it hardly showed except on the leeward side, where it was of least use.

As the event proved, it was also dangerous. In January 1791, the keeper, his

wife, and five children, were suffocated. One child, who was found sucking

the breast of her dead mother, was saved; and the two assistant keepers,

though senseless, were got out alive. The ashes, which had been allowed to

accumulate for more than ten years, reached up to the window of the keeper’s

room; and having been set on fire by live coals falling from the lighthouse,

and the wind blowing the smoke into the windows, and the door below being

shut, the result was inevitable. The two men who escaped declared that a

sulphureous steam was observed to issue from the heap of cinders for several

weeks before the fatal night on which it burst into flames, and therefore it

was supposed by some that there had been a fermentation among the ashes.

Formerly, the families who resided there lived in houses detached from the

tower, and it was now resolved to re-adopt the old plan. In Sibbald’s time

there was “a convenient house with accomodations for a family,” which may

have become ruinous before 1791. Probably this house and the old tower were

built with the stones of the monastery. The architect who planned and built

the tower was drowned in returning to his house, which led to the burning of

several witches who were supposed to have raised that storm. In a

bombastically written book, entitled The Key of the Forth, or Historical

Sketches of the Island of May, the story of the architect and the witches is

spun out to a great length, being made the ground-work of something like a

tragic romance of love. The old tower, which is now used as a look-out by

pilots, still bears over the door the date 1636. As it is supposed to have

been the first lighthouse erected in Scotland, a special interest attaches

to it. Mr Merson states that an earlier light-house existed on the island,

but he gives no authority. The accompanying illustration shows how the coals

were raised.

New Lighthouse.—The old lighthouse was the only private one in

Scotland, and the Commissioners of Northern Lighthouses deemed it wise to

buy the island from the Duke of Portland, who had acquired it by marrying

the heiress of Scott of Balcomie. Accordingly, a bill was introduced into

Parliament authorising its purchase for £60,000. Whenever it became the

property of the Commissioners, they began to erect the new lighthouse, which

is massive and elegant. There is plenty of accommodation for the three

keepers and their families, and an excellent room for the Commissioners. On

the 1st of September 1816, the coal fire was discontinued, and the oil light

exhibited instead. The catoptric or reflecting light was afterwards

converted into a dioptric or refracting one, by Mr Alan Stevenson, who, in

doing so, introduced several important and ingenious improvements.

Operations have this year (1885) been begun to still further improve the

beacon by introducing the electric light, to work which a large

engine-house has been erected. The light-room, which crowns the building at

a height of 240 feet above sea-level, is one of the sights of the island,

and is well worth inspecting. In order to point out the position of the

Carr, and to make the entrance of the Firth safer, another lighthouse was

built on the island in 1843-4. Some interesting notices of the May will he

found in two papers on “Our Lighthouses,” which appeared in Good Words in

1864. There is also a small farm-steading, but the relative fields are few

and small. The latter, when enclosed, have been laid out in the form of a

cross, and are divided among the keepers. One horse, several cows, and a

number of sheep are kept, and poultry besides. The place was lately over-run

with ants; but determined efforts have been made to exterminate them.

Pasture.—Mr Forrester wrote in 1791 that:— “A very intelligent

farmer, who has dealt in sheep above thirty years, and has had them from all

the different corners of Scotland, says, that he knows no place so well

adapted for meliorating wool as the Island of May; he adds, that the fleeces

of the coarsest woolled sheep, that ever came from the worst pasture in

Scotland, when put on the Island of May, in the course of one season, become

as fine as sattin; their flesh also has a superior flavour; and that rabbits

bred on this island have a finer fur than those which are reared on the

mainland.” May mutton is still in some repute, but there seems to be little

faith now in the extra quality of the fleece, and yet the nature of the

pasture may have au effect on the wool. An Australian paper recently

contained an article on the “Change in structure of scrub-fed sheep,” in

which it was stated that these animals having to feed on herbage above,

instead of below, them, were growing longer in the neck and legs and smaller

in the body, and that in course of time there might be produced “a kind of

giraffe sheep—all neck and legs, with small body, little wool, and less

mutton.”

Water.—-Sibbald says that, “the isle is well provided with fountains

of sweet water, and a pool or small lake.” Although there are several

springs and also a small lake, the water is not considered to be either good

or safe. Even the water of the romantically-situated Ladies’ Well is

slightly brackish. And so the keepers are regularly supplied with that

beverage from Crail. Nevertheless, Sibbald’s statement, or a similar one,

has been frequently repeated, in the same way as his erroneously-stated

dimensions of the island, by those who ought to have known better.

Fishermen.—In 1792, Mr Bell said that there were no inhabitants

except the keepers and their wives, but that “there were formerly 10 or 15

fishermen’s families, with a proportionable number of boats.” And Sibbald’s

editor adds, in 1803, that “the want of these families is a considerable

loss to the general interests of the fishery in the Frith; for, placed as

centinels at its entrance, they were enabled to descry and follow every

shoal of herrings or other fish that came in from the ocean.” In the

Burying-ground, which is still pointed out, there is only one grave-stone,

and it is in memory of John Wishart, who died in 1730, aged 45, and “who

lived on the Island of May.” Probably he had been one of the fishermen.

Birds.—There are also inhabitants and visitors of another kind,

bipeds likewise, and very numerous. “Many fowls,” says Sibbald, “frequent

the rocks of it, the names the people gave to them are skarts, dun turs,

gulls, scouts (and) kittiewakes.” Standing on the top of the precipitous

cliffs, it is delightful to watch the fowls circling high o’er head,

nestling on narrow ledges of the rock, or diving in the water 100 feet

below. An interesting paper on the “Isle of May and its Birds” by Mr Agnew,

the head-keeper, appeared in Chamber’s Journal for September 1883.

Caves and Havens.—There are several large caves into which access can

be had at low water, and which are said to have been utilised in former

times by the smugglers. There are two places where passengers can be landed

in good weather, but which are respectively unapproachable when the wind is

in the east or west. At a third point the mails are sometimes landed, and

this leads me to say that no visitor should go without taking newspapers for

the keepers. They are so shut out from the rest of the world

that these are highly acceptable. On the 1st of July 1837, a boat from

Cellardyke, containing 58 passengers, besides a crew of seven, was swamped

at the landing, and thirteen persons, chiefly young women, were drowned.

Boatman. —A better

place for a picnic than the May cannot be imagined. Mr Alexander Watson, the

official “Isle of May Boatman,” sails from Crail every Tuesday in summer,

and every alternate Tuesday in winter. He is also ready to go on any day

with a party, but of course he should get notice. A more cautious or

obliging skipper, or a better guide over the island, could not be desired.

Records of

the Priory of the Isle of May

Edited by John Stuart, LL.D. (1868) (pdf) |