The history of the Scottish people is

largely a history of Scotsmen who have emigrated from the land of their

birth. The Fates decreed, apparently, that it was to be the dark lot of

Caledonia to educate her sons and then send them to far places. All through

the centuries this has been so, nor will we see it changed, for the

practical genius of the Scot, and the more pleasing aspects of his nature,

do not expand freely in Scotland. In order that he may grow, the Scot must

be transplanted while young. Rooted in his native soil he remains hard,

gnarled, and knotty, like a Scotch fir leaning stubbornly against the winds

of a rocky headland.

During the past ten years, 391,903 Scots

left their native land, reducing the population of the country from

4,882,497 to 4,842,980. Of the 391,903 emigrants, 328,000 sailed from these

islands. What became of the remaining 60,000? There is only one answer—they

trekked across the border and settled down in England. No other country in

the world received such copious transfusions of vigorous blood at so little

cost.

Yet Scotland, somehow, survives this

perennial blood-letting. Indeed, in spite of her appalling losses of

population, she has grown, slowly, like the oak, and, like the oak,

hardening her texture in the tedious process. At the time of Parliamentary

Union there were 1,093,000 people in Scotland ; it has taken more than two

centuries to achieve an increase in population of 3,749,980. When we compare

these population figures with those of England, for the same period, we

begin to understand what has been called The Tragedy of Scotland. Only a

hardy breed could survive the conditions that these figures connote.

The earliest Scots did not leave their

country. On the contrary, they clung tenaciously to their barren acres and

their primitive huts, fighting savagely against a succession of covetous

invaders. They defended their dismal hinterland against the disciplined

Roman legions, and with a degree of success that puzzled and irritated the

military masters of Europe. Agricola, with all his skill as a military

strategist, had a hard time battling his way north to the Firth of Forth,

and in that airt he ran into the red-headed Caledonians. It was no use

pitting Romans against these wild men from the Highlands, so, just as a

precautionary measure, Agricola built his line of forts from the Firth of

Forth to the Firth of Clyde. The Caledonians remained in their mountains

till Agricola went back to Rome, then they pushed the forts over.

Rome, however, was too proud to overlook

this sort of thing, and the Emperor Hadrian went north to take a look at

things. He must have seen a good deal of the Caledonians, for he backed up

and built his sod wall between the Tyne and the Solway. This soft barricade

only aroused the curiosity of the Picts and the Scots of the Lowlands, and

after inspecting it carefully they swarmed over it, invaded South Britain,

did some killing, and headed home with booty. Another good Roman reputation

was tarnished.

Lollius Urbicus was the next great Roman

general to be sent against the tribesmen of North Britain. He followed

Agricola's road to the Firth of Forth, and built another huge wall across

the waspish waist of the country, naming it in honour of his emperor

Antoninus. It was a fine achievement in military architecture, but it did

not keep the redheaded raiders in their own territory, and Lollius had to

admit that he was beaten. The Caledonians opposed his massed troops with

guerilla tactics, and in this type of warfare, with cold steel to the fore,

the men from the Highlands were, as they have always been since, unbeatable.

Something had to be done about them,

however. The prestige of Roman arms was at stake. Ignoring his generals, the

Emperor Severus took the problem in hand himself. With an immense army at

his command, he marched into North Britain, and kept on marching till he was

within sight of Lossiemouth. He had killed a number of Caledonians, but when

he came to make a tally of his own army on the shores of the Moray Firth, he

discovered that he had 50,000 fewer soldiers than when he started on his

march. That settled Severus. He made a dignified but smartly executed

retreat to the border, built a stone wall between the Tyne and the Solway,

and sent his regrets to Rome. That was the last

attempt made to keep the Picts and Scots out of

England. Rome, with trouble piling up nearer home, was quite content to

leave the tribes of North Britain [This term is still used to signify

Scotland, and the English are blamed for perpetuating its use. As a matter

of fact, the diminutive letters "N.B." are printed on the notepaper of most

of the county families and successful tradespeople of Scotland to-day.] to

their own devices.

In their turn, the Norsemen

and the Danes had their fling at Caledonia. Sometimes they met with success

; often they were repulsed; always they were stubbornly resisted. They, too,

left traces of their successive invasions, for many of them remained in the

country to which they came to ravish, raising fair-haired, horse-faced,

high-shouldered children. The blood of those vigorous pagans from across the

seas flows strongly in the Orkneys to-day, and further south. Phlegmatic

blood, but strong in courage and with the old love of questing in it. The

pagan pirates came to North Britain to weaken and conquer it; they left it

stronger, and unconquered, but facing the worst enemy it had yet

encountered—England. The fibre of the northern tribesmen was to be tested

and toughened by nearly five centuries of savage warfare with their southern

neighbours.

The lot of the common people

of Scotland at this period was one of perennial poverty, but the stately

ruins which dot the countryside are mute evidence of the certainty that

civilizing influences were at work. The records of the benign and

enlightened ecclesiastical outposts that were established were swept away by

the raging fires of war and religious bigotry; but there is not the

slightest doubt that, nurtured by these centres of culture and learning, the

long-repressed genius of the country flowered briefly in the twelfth

century. [King David I of Scotland (1124-1153) made ecclesiastical history

by his whole-souled support of the Church. He almost beggared the country by

building such famous monasteries as Melrose, Dundrennan, Holyrood, Dryburgh,

and Newbattle.]

We catch glimpses of this

vague but interesting era in the ruins of beautiful monasteries, in

convincing historical evidence that agriculture was on a diversified and

progressive basis in the lowlands, and in the fact that scholars of wide

renown came out of the country. Michael Scot emerged from the mists to

impress England and Europe with his learning :

A wizard of such dreaded

fame, That when, in Salamanca's cave, Him listed his magic wand to wave, The

bells would ring in Notre Dame.

It appears, also, that

Michael studied medicine on the Continent, for he returned to Scotland with

a reputation for the successful treatment of leprosy, gout, and dropsy, and

he compounded a pill called "Pilulae Magistri Michaelis Scoti", which, like

some of these modern pills that are wrapped in pretty boxes, was both

popular and potent. Michael assured Scottish sufferers that it was

"guaranteed to relieve headache, purge the humours wonderfully, produce

joyfulness, brighten the intellect, improve the vision, sharpen hearing,

preserve youth, and retard baldness". Had he lived to-day, this healer would

undoubtedly have thought of many other diseases that would have yielded to

his powerful concoction.

This mysterious character was

born in 1175, and was probably the first Scot who studied at Oxford

University. His passion for mathematics, astrology, and the occult sciences

took him to Paris and Rome, and his genius so impressed Europe that he was

invited to join the glittering galaxy of savants that was a feature of the

Court of Frederick II. While basking in the

sunshine of that monarch's patronage, Michael translated Aristotle and wrote

several books that dealt with astrology, alchemy, and his dark occult

theories. He foretold Frederick's death in 1250, and having guessed well in

that instance, set the date of his own departure from this sphere, adding

the interesting detail that he would be killed by a stone weighing less than

two ounces. From that day onwards he wore an iron helmet. Fate, however,

caught him with his hat off. He was in church one day, and at the Elevation

of the Host removed his helmet. Crack ! A small stone fell from the lofty

roof of the church, killing him instantly but vindicating his reputation as

a prophet of doom. Another faded vignette salvaged from that remote era

shows that the Scots had already begun to take a kindly interest in the

education of the English. It is surely a curious historical fact that Lady

Devorguila, daughter of Alan, the last of the old Kings of Galloway, was the

benefactress of Balliol College, Oxford. Following the death of her husband,

John de Balliol, in 1269, this devout lady built a house in Horsemonger's

Lane, in St. Mary Magdalene's Parish, on the site of the existing college,

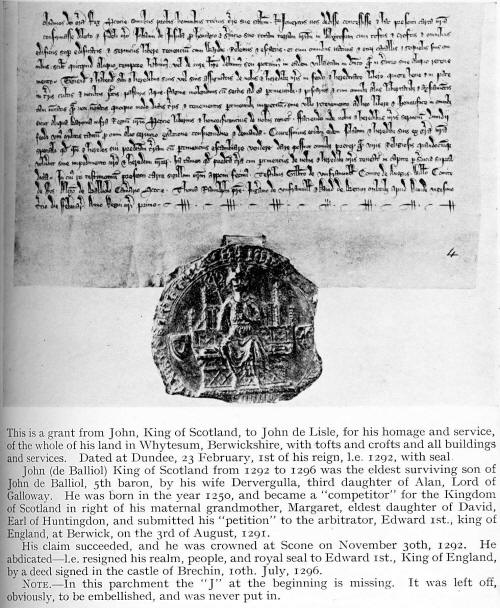

and in 1282 gave her scholars statutes under her seal.

Two years later she purchased

a tenement known as Mary's Hall, which was "to be used as a perpetual

settlement for the principal and scholars of

the House of Balliol". This

domicile was called New Balliol Hall. The revenues of the college in those

days would not buy cigarettes for the brilliant lotus-eaters who stroll

through their studies at Balliol to-day. They produced only one shilling and

sixpence per week for each scholar. Lady Devorguila, however, made up the

deficiencies by substantial gifts, and when she died the college was

supported by her son, King Balliol of Scotland. The son's generosity, in

fact, was so boundless that he ended up by handing Scotland over to the

English, and we will catch a revealing glimpse of the conditions that

produced the modern Scot as we pause a moment to see how Balliol was driven

to the miserable extremity of bartering his country for his freedom.

When that incorrigible

meddler, Edward I of England, bullied the Scottish barons into accepting

John Balliol as their king on the 17th of November, 1292, the bloodiest

chapter in Scotland's history opened. Balliol was a weakling. He tried to

stand out against Edward, and by way of counteracting the latter's pressure,

established the Franco-Scottish Alliance. The fight for Scottish

independence was in earnest, and it proved to be the most gruelling test to

which the tenacity of the race has ever been subjected. Edward led an army

against the prosperous town of Berwick-on-Tweed, and to show the Scots that

he was not a man to be treated lightly when coveted new territory, he razed

the town and put its inhabitants—men, women, and children—to the sword. That

slaughter completed, he led his army north to Perth, and there celebrated

his victories. It did look as if he had crushed the Scots completely, and a

day or two later Balliol, stripped to his underwear, handed the Bishop of

Durham the white wand of abject surrender.

Edward, however, made the

same mistake that so many other would-be conquerors of Scotland made—he

underestimated the unconquerable spirit of the common people. Balliol had

surrendered the independence of their country ; they had not. So, just when

Edward's English satraps thought they had the country tamed, Sir William

Wallace drew his sword in the town of Lanark, and he did not lay it aside

until he met England's soldiers "beard to beard", and had swept the hated

invaders back into their own country. The first great hero of the common

people of Scotland was betrayed by the landed class, who should have been

the last to desert him, and by their connivance he was hanged, castrated,

and beheaded in London ; but he had shown England what made the heart of

Scotland beat strong and true—the courage of the common people. It was this

courage of which Robert Bruce became the symbol after Wallace's dismembered

body had been scattered throughout Scotland ; it was this courage which

sustained the new King in his wanderings following his shabby coronation ;

and it was this courage which, at Bannockburn, on the 24th of June, 1314,

inflicted upon English arms the greatest defeat they have ever sustained in

fair fighting.

England had learned, as Rome

had learned, that she was dealing with a race that would not accept defeat.

Well might Christopher Marlowe put these words into the mouth of Edward

II:

And as for you, Lord Mortimer

of Chirke,

Whose great achievements in our forrain warre,

Deserve no common place, nor meane reward:

Be you the generall of the levied troopes,

That now are readie to assaile the Scots.

The levied troops did not

succeed, however. Scotland's independence had been fought for and won at

terrible cost, and although the struggle against "the auld enemie" was to

last for centuries, the country had been united by common sacrifice, its

real strength had been revealed, and in the white heat of the endless war

against a more powerful country the people were tempered to the hardness

which was to make their descendants the wonder of the modern world.

Their determination to be

free was immovable. A curious proof of this almost fanatical resistance to

England's attempted domination may be seen in the letter which the Barons of

Scotland addressed to the Pope in April of 1320:

We know [they wrote in

Latin], and from the chronicles and books of the ancients gather, that among

other illustrious nations, ours, to wit the nation of the Scots, has been

distinguished by many honours; which passing from the greater Scythia

through the Mediterranean Sea and the Pillars of Hercules and sojourning in

Spain among the most savage tribes through a long course of time, could

nowhere be subjugated by any people however barbarous; and coming thence one

thousand two hundred years after the outgoing of the people of Israel, they,

had many victories and infinite toil, acquired for themselves the

Possessions in the West which they now hold after expelling the Britons and

completely destroying the Picts, and although very often assailed by the

Norwegians, the Danes, and the English, always kept them free from all

servitude, as the histories of the ancients testify.

The sins committed by the

Edwards against Scotland are solemnly enumerated to the Most Holy Father at

Rome; Robert Bruce is praised for delivering the country from the oppressors

; but this ringing declaration, which carries a warning to the Scottish

King, follows:

But if he were to desist from

what he has begun, wishing to subject us or our kingdom to the Kings of

England or the English, we would immediately endeavour to expel him as our

enemy and the subverter of his own rights and ours, and make another our

king who should be able to defend us. For, as long as a hundred remain

alive, we will never in any degree be subject to the dominion of the

English. since not for Glory, Riches or Honours we fight, but for Liberty

alone, which no good man loses but with his life.

Such was the spirit that

sustained Scotland during the early part of the fourteenth century. In those

dark days it could be kindled only in the hearts of a valiant and

intelligent breed, and we are not surprised, therefore, to find the country

giving promise of its future genius by producing, here and there, men who

became eminent in the intellectual world. Even in those far-off days, these

scholarly men found their way into England. One of the first of them was

John de Duns, sometimes called Scotus. He was born at the end of the

thirteenth century, and was the first of the long line of grim and learned

Scots who have held Professorships at Oxford University. John was almost too

good to be true, if we are to swallow the following tribute to his genius,

penned by a contemporary Cardinal:

Among all the scholastic

doctors, I must regard John Duns Scotus as a splendid sun, obscuring all the

stars of heaven by the piercing acuteness of his genius; by the subtlety and

the depth of the most wide, the most hidden, the most wonderful learning,

this most subtle doctor surpasses all others, and in my opinion, yields to

no writer of any age. His productions, the admiration and despair even of

the most learned among the learned, being of such extreme acuteness, that

they exercise, excite, and sharpen even the brightest talents to a more

sublime knowledge of divine objects, it is no wonder that the most profound

writers join in one voice, "that this Scot, beyond all controversy,

surpasses not only the contemporary theologians, but even the greatest of

ancient or modern times, in the sublimity of his genius and the immensity of

his learning!"

It is perhaps advisable to

add that the testimonial was not written by a Scot. It may seem to be a

trifle lacking in scholarly reserve, and the cynic might point out that John

left very little evidence of his sublime genius. Nevertheless, this most

subtle doctor was an authentic character, for he was appointed Professor of

Divinity at Oxford University in the year 1301. Only a hazy picture of him

comes across the intervening centuries, but it is one, if we may judge by

his writings, of a monkish, pragmatic pedant who specialized in turgid

denunciations of unbelievers.

Three centuries were to pass

before Scottish scholars were heard of again, for the weary struggle with

England reduced the country to a state of poverty and ignorance. The clashes

became more serious as the years rolled on. Hatred of England had been bred

into the blood and bones of the Scots; from the end of the thirteenth

century they hated their southern neighbours with a hatred that lay cold in

their very vitals. Back in 1388, just before the bloody battle of Otterburn,

the Earl of Douglas said to his French ally, De Vienne: "My friend, you

shall see that our army shall not be idle, and as for our Scottish people,

they will endure pillage, and they will endure famine, and every other

extremity of war, but they will not endure English masters."

In view of the almost magical

manner in which Scotsmen rise to positions of authority in England to-day,

the last observation of the Douglas was prophetic.

War had become the normal

condition in Scottish life. Armies moved back and forth across the border,

leaving chaos and death behind them. Raiders rode at night through the

debatable lands. There was no peace or security for anybody, and under these

disturbed conditions of existence trade languished, agriculture became a

lost art, and the people sank deeper and deeper into the mires of poverty

and ignorance.

AEneas Sylvius, afterwards

Pius II, paid the country a visit in 1413, and he

had this to say about it when he got back to Rome:

It is an island joined to

England, stretching two hundred miles to the north, and about fifty broad, a

cold country, fertile of few sorts of grain, and generally void of trees,

but there is a sulphureous stone dug up which is used for firing. The towns

are unwalled, the houses commonly built without lime, and in villages roofed

with turf, while a cow's hide supplies the place of a door. The commonalty

are poor and uneducated, have abundance of flesh and fish, but eat bread as

a dainty. The men are small in stature, but bold ; the women fair and

comely, and prone to the pleasures of love, kisses being esteemed of less

consequence than pressing the hand is in Italy. Nothing gives the Scots more

pleasure than to hear the English dispraised.

Much blood was to be spilled

on both sides of the border before the ancient enmity was softened ; but

even so, it is possible to discern, in the turbulent reigns of the Stuart

kings, a gradual but inevitable converging of the destinies of the two

countries. Perhaps the feeling grows upon the student of history because the

Stuarts, with all their faults, indicated that they had a larger conception

of statesmanship than the great majority of the rowdy Scottish barons who

surrounded them.

So, as we enter the sixteenth

century, we see the dawn of peace glimmering dimly on the border. The

darkness lifted when James IV of Scotland married

Margaret Tudor in 1503. That talented man died at Flodden, and his son,

James V, died at Solway Moss; but the very

violence of the fighting which these tragic events connoted seemed to

presage the end of it all, and the light still glimmered over the Pentland

Hills.

Mary, the infant daughter of

James V, succeeded to the throne, and the curtain

rose slowly on the most poignant tragedy of Scottish history. Both countries

drifted further into the angry waters of religious intolerance:

And pulpit, drum ecclesiastic,

Was beat with fist instead of a stick.

Inflamed by the harsh

eloquence of John Knox, Scotland rallied to the Reformation. In England the

fanatics burned bishops at the stake, and Queen Elizabeth became head of the

Anglican Church.

The drama of the century

rushed to its climax. Mary came back from France, married the degenerate

Darnley, fought her protracted duel with the implacable Knox, and at the end

of the pathetic struggle abdicated the throne in favour of her infant son

James. For Mary Stuart nothing remained but the insults of the Scottish

rabble, the long years in English prisons, and the axe at Fotheringay. For

her son James a great destiny loomed up, for on the night of 24th March,

1603, Sir Robert Carey, riding a jaded horse, arrived at Holyrood Palace

with the news that Queen Elizabeth was dead, and two days later another

messenger brought the Scottish King word that the Privy Council of England

had chosen him to succeed the Maiden Queen.