|

RIDING the Marches of the

burgess estates was in days not very remote a tremendous function in Lauder.

It was celebrated on the King's birthday, and the notables of the burgh,

having assembled on horseback before the town-hall, drank his Majesty's

health before proceeding to business. The circuit having been completed to a

point about three-quarters of a mile from the town, it was the custom of the

mounted portion of the company to race from there to the town-hall, and the

last quarter down the straight broad street must have been an exhilarating

spectacle. After this there were lashings of meat and drink, and they

toasted the King and one another, after the old hearty fashion, for the rest

of the day and a considerable part of the night. In those days, too, a man

used to parade the town in the early hours of the morning, thumping a big

drum to get the people out of bed. The morning horn that is still blown down

the main street to summon the cows may prematurely disturb the night-dreams

of degenerate visitors from Edinburgh and the like, but nothing less than a

big drum under the window would presumably have penetrated the slumbers of

the local stalwarts of olden days.

The old kirk of Lauder stood

in what are, now at least, the policies of the castle, and the Scottish

Parliament has more than once sat in it. The present one is comparatively

modern. The natives of these counties, like most east coast Saxons, have no

great gift of song, though hearty enough in the matter of Sunday hymns. What

is sometimes frivolously designated a cock-and-hen choir, seems the rule in

such country churches as I happen to know. That they are still a

church-going people hereabouts, there is little doubt, Lauder kirk, like

others of the kind, being full of men on Sunday mornings. What has vanished,

though within my time, or almost vanished, and mercifully too, is the

long-coated, top-hatted funereal broad-cloth uniformity, which was once so

rigid, even among the labourers, perhaps particularly among them. Nowadays

there seems as much variety and liberty in dress among the men of a country

congregation as south of the Border.

The one moment of the week

when Lauder street presents a really animated appearance is when the stream

pouring down front the Established Church meets the up-flowing tide from the

United Free Kirk after Sunday morning service. The two churches—there are

now only two, unless the Wee Frees, to whom the House of Lords gave all the

cash, are counted—seem to get along well together, though why the dissenting

church continues to set up for itself, since patronage, the old bone of

contention, has long been abolished, no one may judge from ordinary ethics.

The reasons are clouded in subtleties and dogmas that a southerner might

perhaps get a glimmering of if he boarded in the family of a U.F. Kirk elder

for a year, and applied himself at the same time to the controversial

literature of the last eighty years. Maybe, too, there is something in it of

the invincible Scottish conservatism, such as tends to keep the masses

Radical from sheer tradition, and would probably keep them so, as Scotsmen

of the other persuasion declare, if the two political parties exchanged

programmes! The dissenting church has ample funds, so why upset things even

when there is no longer anything left to dissent from in the Church of

Scotland. Tradition, esprit de corps, and lingering jealousies, no doubt,

have something to do with what to the alien seems an anomaly. Perhaps the

tradition of rigid Calvinism, if not always practised, is, in theory at any

rate, dear to the heart of the Scottish dissenter, and he fears the broader

standpoint of the Established Church.

But the rigid sabbatarianism

has enormously softened. Golf and other games are usually barred, but that

is nothing. Cycling, country walks, secular reading are as usual in the

south as in rural England, or, at least, are regarded with apparent

toleration. The herding together at street corners of the young men on

Sunday, is far more of an institution than in any part of England, except

the extreme north. There is nothing theological whatever in these

gatherings, but very much the reverse. Even if not actually ill-mannered, to

sensitive confers and goers of the weaker sex, as inevitable subjects of

collective comment not always leaning to respectful admiration, these

otherwise harmless corner-boys seem rather a blemish to the sabbatarian calm

of a Scottish village. No one, possibly, but some U.F. elder would deny for

a moment that they would be much better employed playing football. One is

almost inclined to long for one hour of the old-fashioned elder, who cleared

the streets with a whip, except that lie would not be over-nice in his

discrimination, and the harmless pedestrian would suffer with the brazen

corner loafer. Times indeed have changed. "D'ye no ken ye're whustlin'?"

even from a servant, whose years entitled him or her to make free in so

solemn a cause, was no time-honoured joke forty years ago, even in the

Lothians, but a readily provoked rebuke on the Sabbath day to light-hearted

youth, though it may be feared he took it as a joke. Scottish Calvinism, in

the person of the preacher at any rate, every one knows had its lighter

side, whereas modern Welsh Calvinism has no gleam of such humanities about

it. It is impossible to conceive a humorous story emanating from a Welsh

chapel, though many good stories come out of Wales. It was an Aberdonian in

Lauder who introduced me to the shade of his celebrated townsman Dr. Kidd,

who was in his day, I believe, a perfect autocrat in the pulpit. A stranger

in a red waistcoat, on one memorable occasion, had taken his seat in a

front. pew, and in a manner made himself unconsciously a mark for the

doctor's eye. Unfortunately he fell asleep at the "fifthly" or "sixthly,"

and the preacher, pausing in his sermon, pointed at him and shouted: "Wake

up that man!" The usual measures being applied with success, the sermon was

proceeded with. In two or three minutes, however, the unrepentant recusant

was nodding again. "Wake up that red-breasted sinner in the front pew!"

shouted the doctor. During the pause that ensued the usual remedies were

again successfully applied by his neighbours, and the backslider was once

more brought up to the scratch. Unintimidated, however, and unabashed, he

was seen in a short time to be once more in a state of unconsciousness by

the hawk-eyed cleric, who this time entirely lost patience. Snatching up a

small Bible which lay handy on the pulpit desk, he hurled it with unerring

aim, and hit the delinquent squarely on the side of the head. "There, sir,"

he cried, "if you won't hear the Word of God, at least you shall feel it."

For the rest of the discourse

there was no more trouble, and the doctor finished his message of peace and

goodwill to his flock without further disturbance. The ash is a prominent

tree throughout Berwickshire. It flourishes exceedingly, and grows in places

to a great size. It was probably grown about farmhouses long before forestry

became a cult of the Lowland Iairds, being useful for farm implements in the

primitive days, and also planted on boundaries. It is an old saw, too, a

propos of its quick growth, that the ash will buy the horse before the oak

will buy the saddle. The mountain ash has everywhere magic virtues. It is

sometimes alluded to as indicating a dark age in Lauderdale, because herds

of cattle a century ago were to be occasionally seen with a branch of the

rowan tree tied to their left horns as a specific against some current

disorder. Rank superstition is not so dead as people seem to think.

Calvinism did not, I fancy, greatly influence it one way or the other in

Scotland. It has almost killed it in the last fifty years in Wales, though

no British people, I suppose, could be more unlike in temperament than those

of the Teutonic districts of Scotland, and the Celtic Welsh. But in an

English parish on the Welsh Border to-day, not at all out of the way, and

almost wholly Anglican in creed, if that matters anything, the mountain ash

is not merely regarded, but utilised for its magical influence in a manner

even more remarkable than its application to the horns of the Lauderdale

cattle 100 years ago. A rite connected with it is firmly believed in as a

specific against whooping-cough, when the complaint is in the village. A

particular rowan tree, standing in a wood a mile away, is resorted to, a

small incision is made with a knife in the trunk, and a hair of the sufferer

is inserted in the slit. The trunk of one is entirely scarred with these old

marks, and an adjoining tree has been commenced upon within the last three

years. At this moment there are two or three fresh incisions, with lately

plucked hairs adhering to them, and I have seen them and touched them within

the last few weeks. Furthermore, natives of the parish living in distant

parts seem to retain their primitive faith, and, when this juvenile ailment

is in the household, send hairs home to their friends to insert in this

magic tree in the heart of a wild wood. In a too curious inspection the

other day, I accidentally snapped a fresh one, and have felt vaguely

uncomfortable that a whole family may be still whooping on that account.

Some archaic accessories to

wedding celebrations are even yet kept up in Lauderdale. "Running the brae"

is one of these. This is performed by the attendant youths, who race across

a field, the goal and prize being a silk handkerchief, held at the corners

by the bride and bridegroom. The winner also kisses the bride, and wears the

handkerchief as a trophy at the ensuing dance. Cradling, which was mentioned

as being long extinct in the Merse, is, I am credibly informed, still

occasionally practised in Lauderdale. Railroads are commonly credited with

the destruction of these old-world customs. The railway to Lauder may have

killed its posting business, but as a disturber of rural peace and

simplicity, this one may surely be regarded with equanimity!

Penetrating the sentinel

heights that guard the vale, of which Boon Hill, though it carries no camp,

is the most conspicuous, an interesting, rather solitary country spreads

away eastward along the foot of the Lammermoors, towards the Merse. The

moors here present no bold wall, such as does their northern side to the

dwellers in Lothian plains, to golfers upon distant shores and to ships upon

the sea, but spread gradually downward in wide breadths of reclaimed or

half-reclaimed land, merging by degrees with the normal landscape of the

lower level. At the edge of these moorish, half-tamed, and thinly planted

sweeps, which trend upward to the heather, lies the ancient seat of the

distinguished house of Spottiswood of that ilk. Not ancient in a literal

sense, for the building is comparatively modern, and is, I believe, only

occasionally occupied by shooting tenants. It stands amid fine old timber

upon a long southerly slope, with far-stretching belts of well-grown

plantings enclosing its home pastures. There is about it that measure of

fascination, which a certain aloofness from the world, and a rather lonely

surrounding country, seems to impart by very contrast to a snug and

luxuriant abiding-place in its midst.

The Spottiswoods of

Spottiswood are a very ancient stock, and have contributed men of mark to

Scottish history since time in such things began. An Archbishop Spottiswood

of Glasgow crowned Charles I. at Holyrood. His son was Secretary of State,

but in 1643 was captured at Philiphaugh, tried by the Parliament, and

executed. Another son of the house was Governor of Virginia early in the

eighteenth century. He was very popular, and excellent company, and tales

are there told about him to this day. A great many title-deeds in that

ancient commonwealth start with his signature, being originally Crown

grants, as he had a fancy for exploring in a comfortable sort of way with

plenty of congenial friends, spare horses, servants, and good meat and

drink, and granted a good deal of what was then wild land to all he had a

fancy for. I had his signature and seal myself in a tin box on this account

for several years, though in a century and a half it had grown very wan and

yellow. The well-known London printing house of Spottiswoode is a

comparatively recent offshoot of this interesting cradle on the slopes of

the Lammermoors.

But far the most vivid

personality connected with its more recent ownership is Lady John Scott, the

heiress of the house, who married a son of the Duke of Buceleuch, and came

back here to spend a long widowhood, and to die only about fifteen years

ago. She was a notable personage, and well known to all ranks throughout the

country. She had a keen taste for literature, for antiquities, and folklore,

a passion for her ancestral home, and all that pertained to it. She wrote a

good deal of poetry—some of it in the vernacular, or, to be more precise, in

the old Scottish tongue. There is not a Scot in the world, I suppose, or an

Anglo-Saxon of any kind, of middle age or over, who does not know " Annie

Laurie." Lady John Scott wrote it, or rather edited an impassioned

out-pouring of a Kirkcudbrightshire laird, by name Douglas, on the Miss

Laurie of Maxwelltown, who was breaking hearts—his, at any rate, we must

suppose—about the year 1700. It required some editing! I have seen the

original version, and can remeznher one verse. It ran, I think, thus:—

"She's backit

like a peacock,

She's breasted like a swan,

Her face it is the fairest

That e'er the sun shone on,

That e'er the sun shone on.

She's jimp aboot the middle

And she has arollin' e'e;

An' for bonnie Annie Laurie,

I'd lay me down and dee."

The gifted lady of

Spottiswood had a fine enthusiasm and feeling for her native soil, and what

is more, lived upon it. She had just a little weakness for erecting curious

stone archways and other little monuments here and there, which may cause

brief shocks to the scarce wanderer taken unawares in his pilgrimage along

the leafy ways of Spottiswood. In the Lodge, by the same hand, is embedded a

stone bearing a Latin inscription not worth recording here, which was

brought from Archbishop Spottiswood's house in Glasgow. The place generally

looked rather forlorn, and the outskirts of the policies not a little

unkempt, as if the glory had departed. But it was a chill drear autumn day

when I was there. The leaves shivered above in the high beech trees, and

moaned in the pine woods. The Twinlaw Cairn, which I had hitherto failed to

reach, showed close at hand on the edge of the Lammermoors, the two cairns

standing boldly out against the sky on the summit of a broad hill, and their

story is dramatic to a degree.

A body of English, how

composed and by whom led is not revealed, invading this country on a certain

occasion, was met by a Scottish army just here on this southern slope of the

Lammermoors. When the two sides were arrayed for battle, the course which

James I1'. in later days at Flodden is said to have proposed to Surrey,

though in that case in the person of their two illustrious selves, struck

one of the two leaders as a happy notion. It was a pity, he urged, that so

many brave men should be sacrificed, while the issue could just as well he

decided by a champion selected from either side, and provide entertainment

at the same time for both armies. This was agreed to, and champions having

been chosen they rode out between the armies, and a fierce encounter ended

in the victory of the Scottish warrior.

Like lions in

a furious fight,

Their steeled falchions glean,

Till from our Scottish warrior's side

Fast flowed the crimson stream.

With deafening din on coats of mail,

The deadly blows resound,

Till the brave English warrior

Did breathless press the ground."

Thus a seventeenth-century

ballad celebrates in long shadowy retrospect the clash of arms. But it was

then came the real part of the tragedy. . For when the father of the

victorious champion, Edgar of Wedderlee, which adjoins Spottiswood, gazed

upon the expiring Englishman, as was supposed, a cry of agony burst from his

lips. For he recognised by some unmistakable mark a son of his own that had

been carried off in childhood by English Borderers, and reared as one of

themselves, and that he had in consequence been slain by his own brother. So

the two armies in sorrowful sympathy for the grief-stricken parent and

brother on the one side, and the gallant dead upon the other, set to work to

build two cairns, passing the stones from hand to hand from the burn beneath

to the high ridges where they now stand, conspicuous to the eye over half

Berwickshire. The farm of Flass lies at the foot of the sloping moors, just

beneath them ; and as we were lately on the subject of superstitions, it may

be noted as having been in 1736 the scene of a sacrificial offering of a

horse, which was burnt alive during some malignant disease among the stock

of the neighbourhood.

Walking down from the groves

of Spottiswood over some rough pastures and some apparently unreclaimable

mosses to the hamlet of Wcstruther, Wedderlee, in full sight of Twinlaw

Cairns, stands as it should, rather sadly in a patch of woodland upon the

long foothill sweep, fulfilling now, I think, but a modest function. The

Lammermoors roll away behind it, and the two Dirrington laws, near

Longformacus, rise cone-shaped against the horizon. The Edgars had to sell

it in 1737, and the departure of the only son and heir from the halls of his

ancestors was delayed till nightfall—to throw an appropriate gloom over the

occasion, says a biographer; while the country folk handed down the fact in

its double significance: "It was a dark nicht when the last Edgar rode out

o' Wredderlee." There even exist writers who have seen in him the original

of Edgar Ravenswood. Westruther is an isolated hamlet, and possesses an

ancient but abandoned little kirk of barn-like device, with broad stone

stairway and platform outside each gable-end leading into the galleries like

the steps up to a granary or loft. There is also an old stone mounting

block, and more graves in the wide green churchyard—Edgars of Spottiswood,

no doubt, among them—than you would fancy this sparsely peopled country

could have filled in a thousand years.

For three miles below Lauder

the river curves between its red banks through wide meadows, and shorthorn

cattle cool their legs in its stony shallows. By the roadside here and

there, beneath the shadows of umbrageous oaks and soaring ash trees, stand

real old-fashioned homesteads in which, or upon their sites at one time or

another, lived various members of the Lauder clan. One of these, St.

Leonard's, has a Latin inscription let into the wall of what is held to be a

fifteenth-century chapel, and of which I could only make out that the first

four words were "Deus est Eons vitae." The highway crosses the Leader to its

eastern bank by a stone bridge, which may he aptly regarded as dividin;

Upper from Lower Lauderdale. Berwickshire, too, here crosses the river,

which henceforward, running down to Earlston and the Tweed, parts that

county for much of its beautiful course from Roxburghshire, with its

disconcerting habit of thrusting fragments into the vitals of its

neighbours. There are no more meadows and farms in the valley now. The hills

press in, and, for the most draped in tangled woods, rise to an imposing

height above the Leader, and leave it but a narrow trough in which to fret

its downward way. It is a beautiful gorge, whether standing in the clear

stream below or looking down from the high road far above through vistas of

foliage on to its flashing waters.

The angler for a purely

nominal consideration can fish practically the whole of Upper Lauderdale,

and down this lower wooded glen to the beautiful seat of Carolside which

lies embowered in its depths. The Leader is a natural trout stream of the

finest qualities, and in emulating the achievements of the widow's cruse,

and keeping up its stock against unbridled onslaughts, it is even more

wonderful than the Whiteadder. For it is neither so long, nor fed by so many

tributaries, nor so inaccessible as the upper portion of its easterly

neighbour. It is a silvery rather than an amber stream as the other, a

distinction which the fisherman, at least, will recognise. Fishing, as will

be imagined, is a popular pursuit in Lauderdale, and the native angler has

to Put up betimes with the company of strangers from all the south-eastern

towns, as well as from Edinburgh and even the Lanarkshire collieries.

Fishing clubs, native and alien, hold competitions here, and yet there are

plenty of trout. Heaven knows why, and yet I can swear to it from ocular

demonstration! though an east wind, a bright sky, and low water were not

conducive to heavy baskets. But such testimony is neither here nor there. In

the club competitions the baskets are weighed with jealous care, and the

results are printed in the Scotsman and other papers. There is no room for

embroidery on these occasions at any rate. Here, as in the Whiteadder, ten-,

twelve-, and fourteen-pound baskets—which may mean anything from twenty-five

to fifty fish--are quite often scored by the prize winner, to say nothing of

the much greater number of unrecorded private achievements on other

occasions. And with all this, as good a judge as there could well be told

inc the river was actually improving, and that he had killed this year more

large fish between one and two pounds than he had ever done before. I leave

this problem, like that of the Whiteadder, for he to solve who may. It is no

use discussing the mystery with Scotsmen of these districts, who think it is

natural and have never been used to anything else. They take it for granted

that no amount of rod-fishing, fly or worm, makes any difference to a river,

and that the supply of trout the next ti car will always be found equal to

the very formidable demand. And so it is, and has been apparently ever since

the time of Robert Bruce, or William the Lion. I should be inclined to

gather, however, from riverside traditions and printed statistics, that the

catches probably fell off very much about forty years ago, but I can see no

sign or find any evidence that they have fallen off since, which is all that

matters. At any rate, the above figures speak for themselves, and no

pessimistic note is ever heard on these riversides, such as on English

mountain rivers, by comparison almost unfished, is so chronic.

The Leader, like all these

Border rivers, is fished more with worm than fly by the humbler type of

artist, who generally pockets every fish, however small, and yet it

flourishes ! An angling competition where fifty competitors sit upon

camp-stools in a row by a sluggish river watching a float seems quite a

reasonable entertainment and not out of harmony with this more sedentary and

gregarious form of sport. But to the southern sportsman a competition of

fly-fishers ranging for miles through nature's most beautiful and secluded

haunts, is generally an abhorred notion. Among companions, to be sure, there

may be at times a certain suppressed sense of rivalry in a day together, but

the principle of competition is inadmissible and rigidly disclaimed. It

spoils trouting. But Scotsmen, though not all, of course, revel in it. The

Edinburgh clubs vary, I fancy, in their social ingredients, some consisting

of the higher, others of the humbler members of society. Occasionally, I

believe, the competition is confined to one river—any unpreserved part of

it. At other times the competitors may select any water, provided it is not

a private preserve. I think both fly and worm are usually permitted, for the

latter in clear water is rated in the north as equally artistic. From the

facts here given, the reader may derive the natural impression that with a

nation of fishermen these streams would be lined with anglers. But this is

really not the case. The working-man may be fairly constant in the evening

upon handy water, and on really good (lays is much in evidence, provided he

can get away, which, after all, is not often.

In the first half of a bright

September under unfavourable, but by no means impossible conditions, eight

miles of the Leader lay almost as unnoticed as a duke's preserve, and I had

a few half-days which, if not prolific, were by no means barren, and always

delightful for the charm of the river itself and its surroundings. One day

about noon, after successfully outwitting a half-pound fish that was rising

in an overhung pool beneath the old Lauder pele tower of Whitslade, I espied

an angler—a gentleman obviously, with two attendants—coming upstream in the

water. I sat down and waited for him in anticipation of those friendly

interchanges of current experiences, and such like, that are customary

between strangers on the river bank. He was thrashing away, too, at a great

rate, and in the apparently careless fashion of a man who has done his

serious work, and is going back to catch a train or trap, for which, on this

particular day, there seemed ample reason. "What is the matter with the

fish?" he called out as he got within speaking distance.

I said I didn't know, that I

had been out since ten and only had half-a-dozen.

"I have been out since

eight," he said, "and have only seven." So I thought we were going to have a

comfortable chat, particularly as he was a stranger, and on the look-out for

local tips. Not a bit of it. He went down into the water again just above

me, and flogged away for his very life. He had a man on the bank with a

landing net, and another attendant, who proved to be the river watcher; for

soon afterwards he caught me up to crave a sight of my ticket (a half-crown

one, good for a year). "Who is that gentleman?" I inquired. "Why, that's Mr.

B.," with a note of surprise, almost of reproof. "And who is Cllr B.? I.

suppose he wants to catch the two o'clock train at Lauder."

"Mr. B.! I. thocht ye'd hae

ken't who he was He's won the gold medal of the club in Edinburgh twice

running, and if lie wins it the day he keeps it for his ain."

"He's not running for the

train, then?"

The watcher thought this a

great joke, though it wasn't intended as such.

"Na! na! he won't be awa'

frae the river afore nicht, and he's the only member on the Leader, too, the

day."

"Where are the others?"

He mentioned several other

streams of familiar name within forty miles of Edinburgh, over which they

were presumably distributed.

After another half-hour,

inspired by the superhuman energies of the gold medallist, which proved

things to be getting worse instead of better, I reeled up and went home,

devoutly thankful that I was not entered for a piscatorial Derby and my

reputation committed to a breathless ten-hour fight against untoward

conditions, Next day in Lauder I met the man who had been carrying the

landing net for the Edinburgh champion, and naturally put the inevitable

query. The northeast wind, and the glitter of the day had defied all the

efforts of even so great an artist, and I learned that only a single fish

was the reward of a whole afternoon's labour. But my informant turned out to

be the local champion, and, according to his own account, he had arranged a

private match with this hero from the metropolis, to which he looked forward

with apparently the utmost confidence.

Down in the leafy depths

below, towards Earlston as I have said, lies Carolside. A modern house, but

on the site of an old one, it is surrounded by gardens of some repute, while

the Leader races along the foot of the well-timbered sloping park, overhung

on its further side by red sandstone cliffs, feathered by wild woods. Back

in the hills on the Berwickshire side, and reached by a steel) road, is

Ledgerwood, familiar to antiquarians for the Late Norman chancel still

embodied in the present kirk. My own acquaintance with this interesting

uplifted corner had been already made under the pleasant and illuminating

auspices of the Berwickshire and Northumberland Natural History and

Antiquarian Society. It rained steadily, however, and with no little vigour,

for a good part of the day. Philosophy and zeal were both required on the

part of the members of both sexes, and were not, I think, found wanting. The

landscape was a wet blur, but the Norman chancel arch, and some interesting

old mortuary inscriptions and other details were at least tinder cover.

Keeping the rain out and the heart up, in a full brake on a wet day, when

the open country is the chief raison d'etre of an expedition, is a true test

of umbrellas, waterproofs, and philosophy. But, at any rate, a company

neither `vet nor despondent sat down afterwards to dinner at the hotel at

Earlston.

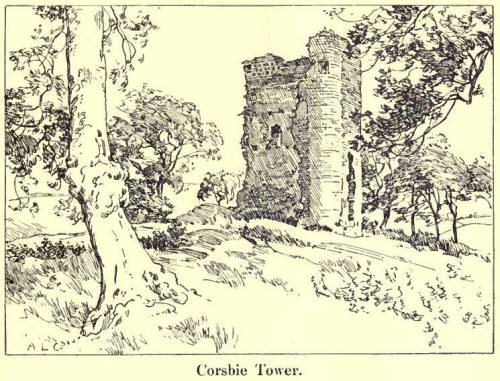

A half mile below Ledgerwood

church, in a marshy flat that once made a virtual island of the green knoll

on which it stands, is Corsbie Tower, an old pele of the Cranstouns, who, it

will be remembered, assisted at the wiping out of the last active Lauder of

Lauder. And reverting once more to that notable family, Carol-side seems to

have been actually the last spot owned by any of them in Lauderdale. An

eccentric old gentleman, says a recent historian of the family, well known

in Edinburgh, where he mainly lived, as Beau Lauder, wore garments so

belated in fashion as to be the sport and joy of the city gainins, who

dogged his steps. For long after such decorative apparel had died out, the

cocked hat, scarlet coat, laced ruffles, silk stockings, and shoes fastened

with gold buckles studded with gems, of Beau Lauder were familiar upon the

streets of Edinburgh. But his means, apparently, were not in accord with his

gaily-caparisoned exterior. He lived alone, and was accidentally burned to

death sitting in his chair in 1793, thus extinguishing the last family links

with Lauderdale.

At Earlston, the narrow

valley of the Leader opens for a short space, and the little town lies

pleasantly above the river, where the road and railroad from Gordon, Duns,

and elsewhere come through an opening in the hills. Earlston has little of

the external quaintness of Lauder, and, being on a through railroad, and

near things, and doubtless busier, has probably few of those archaic

characteristics which make the other a place unto itself. But Earlston has a

genius loci of very high distinction, in the shade of Thomas of Earceldoun

(an old name for Earlston), better known as Thomas the Rhymour; and what is

more, the very thirteenth-century stone building now smothered in ivy, which

formed his residence, still stands conspicuous for all to see.

Concerning Thomas the Rhymour,

his poetry, his prophecies, and the mysteries associated with his name, Sir

Walter Scott, in the Minstrelsy, gives practically all the known historical

facts. His period trenched so closely on that of Wallace, Bruce, and Edward

I., that he apparently foresaw the coming dangers to Scotland. A Saxon in a

North Saxon land, he is supposed to have absorbed the old Arthurian Cymric

legends, and to have applied them more or less to the situation of the

Lowland Scots, threatened by the power of Edward I. In his lifetime he was

regarded as a seer, and at his death prophecy and its fulfilment were freely

attributed to him. He is thought to be the author of Sir Tristrem, a version

of the Cymric legend, best known in the form of Tristrem and Yseult. It is

written in the North Saxon vernacular, and is one of the earliest, if not

the earliest, specimens of English style. The fragments of poetry attributed

to the Rhymour deal with mystery and adventure, and in descriptions of

Nature, both in her summer dress and in her savage and weird aspects. He was

spirited away by an amorous Queen of the Fairies, with whom he dallied for a

long period in fairyland, which gave his utterances and prophecies naturally

greater weight. lie is mentioned by several writers of immediately

succeeding generations, and it seems that his wraith had the credit of

wandering about amid the scenes in Lauderdale where he had walked and

written so much in life. In short, there is a curious blend of undoubted

authenticity and mystery about the man and his works, and they have been

always an attractive subject for speculation and controversy. Among other

things, his predictions as to the union of the crowns were freely quoted,

much as were those of the early Welsh bards foretelling the settlement of

Anglo-Welsh animosities by the succession of a Welsh prince to the throne.

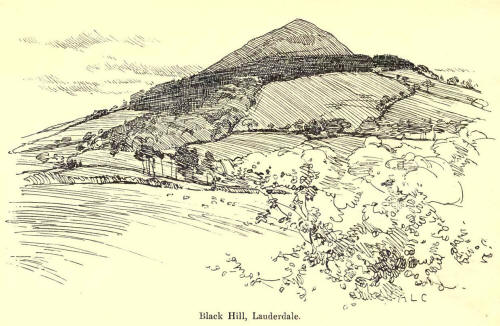

Still onward between the two

counties, through beautiful and woody depths with sloping timbered parks and

pastures, and bosky steeps, shooting up into lofty, and here even rugged

hills, the Leader for these last four miles pursues its resounding course.

Much of it runs through the estate made familiar by the well-known Scottish

ballad "The broom of the Cowden knowes," which together with that of "Leader

haughs and Yarrow," was written by Crawford 200 years ago. The high road

winding along the breast of the hill above towards the Tweed and Melrose

affords a continuous view of what is, perhaps, the most striking bit of

Lauderdale, with the Black hill lifting its pointed cap a thousand feet

above.

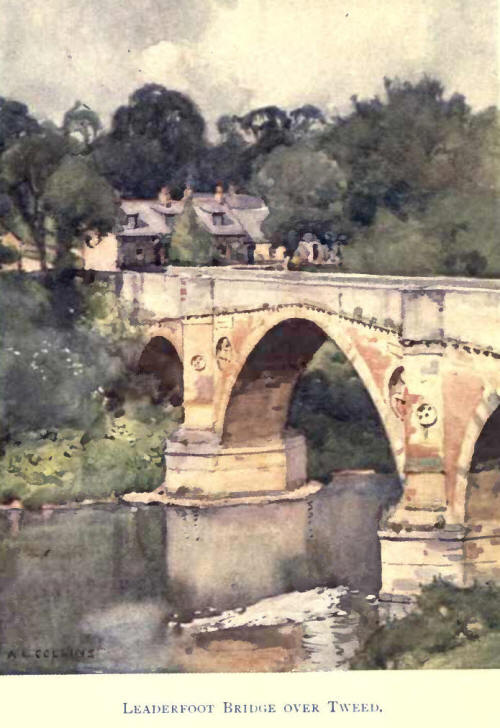

Both the Leader and the

highway, the one to deliver its tribute, the other to mount a noble old

stone bridge, join the Tweed within almost a stone's-throw of one another.

It is a fitting place to end our journey. For the downward prospect from the

many-arched stone bridge of the broad shallows of the greater river into

which the Leader rushes out of her woody depths is a scene well worthy to be

numbered among the fairest we have wandered in all these chapters. I may

fairly leave my reader to cross the Tweed under other auspices into the

Scott country, and into scenes celebrated by pens innumerable. The scheme of

my modest intentions ends abruptly here at Leaderfoot. hitherto we have not

often trodden upon soil, whether plain or mountain, that is ever pressed by

the foot of alien travellers, or that the outer world, speaking generally,

knows anything about. Across this bridge, however, the situation wholly

changes. Up to its first arch my conscience is in this respect tolerably at

ease. The bridge at Leaderfoot might almost stand for the Rubicon between

the known and the unknown. Beyond it both our pen and pencil would most

assuredly lose such justification as I have ventured to proffer for them. A

sense of the fitness of things, so far as this and our pleasant labours are

concerned, calls here for an abrupt halt, and none too soon, for the

limitations of space to which I had proposed to confine these chapters. Just

beyond, the Eildon Hills with their

sharp peaks rise high into

the sky. Melrose, Abbotsford, and Dryburgh are all close at hand. And there

are further changes, too, of another and assuredly less pleasant kind, as

you cross over from the seclusion of Lauderdale into the Scott country.

Nothing, to be sure, has sullied the reposeful seclusion of Dryburgh, the

stately ruins of Melrose, or the suggestive charm of Abbotsford within their

several hounds. But villas, hotels, and hydros, the dust of brakes, motors,

and hired traps, the going and coming of tourists from many lands, make

their immediate neighbourhood seem almost like another world to any one

coming suddenly out of the quiet local life of the Merse, the Lammermoors,

East Lothian, and Lauderdale. |