IN THE HIGHLANDS AND IN HIS FAMILY.

The privilege of having for many years enjoyed the

constant presence of a man of true genius can never be forgotten. And if

remembrance might recall much of the wealth of Professor Wilson's great

intellect, yet rather does it boast to acknowledge the "good words,"

with which, during his sojourn upon earth, he soothed the sorrows of

dependents, or rejoiced the hearts of children. Nothing was more

interesting than some one of those rural rambles which I had the

opportunity of enjoying in his society—days which stand out from the

circle of time as favoured spots in my memory.

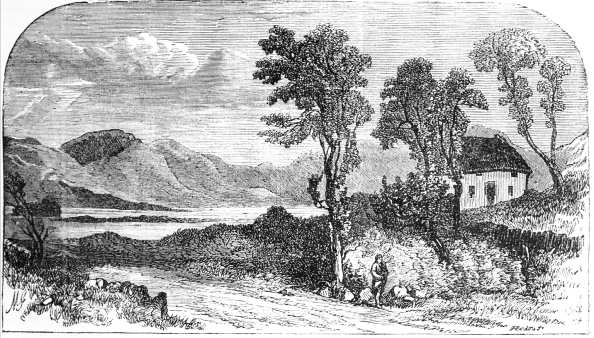

No place was more frequently sought or seen than the

beautiful mountain-land of the Highlands, where, for days, by the banks

of Loch Awe, John Wilson would wander in silent meditation with the

things of nature. His enjoyment was then intense; and his countenance,

as it lighted up in the presence of a beautiful scene, was in itself a

study. His bright, clear blue eye rested upon the landscape with an

expression of love and gratitude. His own fine words describe the effect

of some such scene upon his own mind—

"The sterner thoughts of manhood melt away

Into a mood as mild as woman's dreams,

And leave the soul pure and serene

As the blue depths of heaven."

Ben Cruachan was an almost constant object of his

admiration; and the head of the Lake at Cladich was the chosen

resting-place during his sojourn in that region. Many were the views he

selected as suited for the skill of the artist; and often he regretted

his want of powers to transcribe with the pencil what he so nobly did

with his pen. Although he had an intuitive knowledge of art, and was led

directly, in a picture gallery, to the best paintings—detecting, even in

inferior works those marks of excellence which an ordinary eye would at

once have passed over, and have condemned the whole as worthless—he

exercised a somewhat tyrannical command over any one who possessed the

accomplishment of drawing, not unfrequently insisting upon

impossibilities, and expecting that something in the landscape more than

the art could easily admit should be introduced upon the canvas.

Firm and stately in step, with a free and joyous look

would he walk, anticipating the pleasures of a long summer's day.

Entering a boat, a few moments found it gliding silently over the glassy

surface of the water, among the bays and islands of this fairy place,

resting where fancy led him; alternately gazing on the beautiful scene

before him, or reading some favourite poet, and not unfrequently

conversing with the boatman, who was guide for the day's excursion. One

island in particular was a favourite point of rest, and there he always,

for some short time, would wander about, or, sitting down, with a volume

upon his knees, was soon lost to the recollection of all outward things.

Spenser's "Fairy Queen" was the subject of his mental occupation during

this summer's ramble, and an essay upon which is well known to readers

of hia works to form one of his noblest criticisms.

Once, while rambling about this island, a beautiful

and picturesque tableau appeared, passing in solemn and striking effect,

which did not fail to call forth what was ever one of the most

remarkable traits of Professor Wilson's mind, a tender and ready

sympathy in the hour of sorrow. Rising from a large stone which he had

selected for his seat, and laying down the volume of Spenser he had been

reading, he stood close to the edge of the island; his still uncovered

head was raised | erect, and he watched, with a sad eye and grave

countenance, the approach of a boat that slowly and silently took its

way across the waters towards a long, bare island, that lay like a green

snake on the face of the lake. "Hush!" said he to his daughter; "it will

pass close by us;" and he bowed with reverence to the heavy, dark boat

Professor Wilson—from a cameo.

as it skirted the edge of the island upon which he

stood. It was a funeral party, bearing to his last home a poor old

Highland cottager; there were men and women sitting on either side of

the coffin, which was partially covered with a tartan plaid, upon which

lay a large sprig of heather. At the head of the coffin stood, with a

sad and downcast expression, a young man, brown and weather-beaten,

rough in exterior from hard labour and exposure. He was the chief

mourner; near to him sat a very old woman, too far on her own journey

near the other shores of life to evince any outward expression of grief.

But over the whole company there was visible that decent and grave

bearing never at any time wanting at a Scottish funeral. Each one had

doubtless his own awe-struck feelings awakened by the thought of that

"day when he goes down to the grave to await the judgment of the Lord."

Solemnly following the slow and measured stroke of the oar, the only

sound which fell upon the ear at that moment, he watched the

sad-burdened boat, that formed a melancholy contrast to the broad light

of the mid-day sun that gilded every object upon which its rays fell.

While the grassy grave received the last green sod which was to inclose

for ever his aged remains, the warm-hearted Professor, with words of

sympathy linked the inevitable doom of the loftiest and the lowliest in

our common pilgrimage.

Our ramble was prolonged to Kilchurn, and often was

arrested by views of unequalled beauty. But the little incident now

mentioned was soon perceived to have induced a mood of mind too habitual

to his deep and constant heart.

Professor Wilson had one image that never left him

day or night, and seldom failed to plunge him into a state of mental

dejection most touching to witness. The death of his wife lay heavy upon

him. He long continued to suffer the most poignant grief for her loss,

and never altogether laid aside the sorrow of mourning. He sometimes

spoke of her, and never did so without drawing tears from the eyes of

those who knew how he had loved her. It is certain he never ceased to

think of her. The night she died he was nearly bereft of reason. But God

strengthened him, and he survived for seventeen years the chosen

companion of his life.

In the outward nature he loved so well, many a fond

hour was spent. Nothing escaped his eye ; as ready to find amusement as

instruction, he read the book of nature under every phase, extracting

from objects which the every-day observer would pass over as unmeaning,

an interest that clothed what he saw with new life. Never was he more

charming than when so inspired ; for his power of eloquence required not

the loud applause of hundreds to give it éclat—it

was as noble, proud, and unsurpassed in the fastnesses of the Highlands,

before his own child and a rude and ignorant peasant, as it could be

within the walls of a university. If his subject was philosophy within

doors, it was the philosophy of nature without; if the one subject found

its text in the wisdom of the learned who had taught before him, the

other found its text in the wisdom of God, who was the beginning, and is

for ever.

How often the remembrance of that fine countenance

must visit the memory of those who have seen it kindled by the kindness

of joy, or saddened by the gloom of sorrow. The deep music of that

voice, too, can never pass away to be forgotten as an empty sound, for

it was full of genuine love and feeling, speaking to the heart, and to

be trusted to the last. If John Wilson had possessed no other gifts of

nature to distinguish him, he would have been distinguished by one at

least—a total absence of affectation; clear and open as day, he walked

the earth an upright man, without disguise ; a nobility of nature, which

needed not rank to mark his birth, gave to his bearing something which

art has never been able to give, so that the actual presence of this man

lives in memory alone.

Having gained some cottages after a slow and steady

pull up the hill—interrupted now and then by sudden stoppages to look

round at the lake gleaming with light, and laden with endless

reflections, so that the eye saw as it were two lakes, and all the

mountains and islands preserved in an unbroken mirror of glass—not a

word was spoken, no epithets of admiration fell upon the silence of the

hour, but the whole figure of the man was roused into one embodied

voice—his soul was moved within him—expression's marvellous power

conveyed more than the rapture of human tongue. Adoration could tell its

story another way; but no one ever had such power in the passion of

silence as this true and unaffected son of nature. The name of these

cottages and that of the inhabitant of one of them has escaped my

memory. He had been a student in days past of Professor Wilson's, and

was at that time schoolmaster in this retired spot. A short rest in his

snug little parlour, a glass of milk, and other hospitality, was

partaken of, with some kind words of remembrance and pleasant talk.

Approaching sunset, and limited time to return to Cladich by the lake,

would not permit of a long seat under this humble roof.

Cladich, Loch Awe

A view, too, was to be looked at from the high ground

at the back of the cottage—this was imperative. So sauntering onwards, a

tempting grassy knoll, covered with wild flowers, offered still further

repose from a somewhat fatiguing walk. Sitting down, a new object of

interest was evidently discovered. Upon a small tuft of grass, quivering

beneath its weight, waved heavily from one blade to another, a large,

woolly, yellow honeybee. In an instant, that kind blue eye saw the sad

case of the hapless insect, whose preservation in life and restoration

to health began without loss of time. "Poor fellow," said the Professor,

"he is evidently very sick, we must try and restore him; no doubt, he

has come a great distance. He is completely done up. Not a leg to stand

upon. Don't hurt him. Leave him to me; I will manage the fellow. Come

along, sir," and so saying, he gently lifted the honey-laden bee, and

laid it upon his hand. "He is far too sick to think of stinging,

otherwise I would not trust such a glorious fellow. What a size he is!"

The poor bee, confused and faint, weakly tumbled from side to side on

its long way across the broad palm of its preserver's hand. "Look at

him; he is better already—the sun revives him. He is a cunning fellow; I

believe he knows that Kit North, who loves all living things, is at this

moment watching over him. Now, sir, how do you feel? Ah! there he goes;

I fear his end is at hand. No; he is better again. We shall change his

position; even a bee is a discriminating creature, and hates monotony.

There now, sir, creep upon my coat sleeve; you have all the world before

you where to choose a place." Slowly, more steadily and surely, the

large, gentle bee, crawled, with an effort of revived life, up the folds

and down the creases of the coat, and at last secreted itself in a dark

fold, where, out of sight, it formed new strength to enable it in a

short time to creep from its hiding-place to encounter the beams of the

evening sun. Once more visible, his kind friend encouraged him to open

his wings, which once or twice most ineffectually he tried to do. At

last, with a mysterious and sudden energy, and a strong buzz of

animation, he flew right away, and was very soon lost in the blue ether

on his way to the land of his fellow bees. "He is the finest bee I ever

saw; I should know him again among a thousand. How very sick the poor

fellow was; nothing but fatigue, however; he is all right, and by this

time the hive rejoices in the sound of his voice."

Nothing can be imagined more purely simple and

enjoyable than those wanderings in the country. The Professor laid aside

every care, and threw himself as it were into the arms of nature. All

day long, a voice of rejoicing animated those who were with him; and, as

has already been remarked, his silence was not less instructive than his

eloquence, for it indicated reverence, meditation, and inward communion

with the Invisible.

John Wilson had no one quality, physical or mental,

in measured portion, but a redundancy of all. But there were moments

when this luxuriance was cast aside, and these were in the quiet

retirement of his house, when he carried about in his arms his infant

grandchildren, and tended them like a nurse. Many an hour was spent in

the society of this dawning life. In the midst of this happy band

endles3 plans Were devised to amuse, enliven, and improve their minds.

He even de-dared that no one understood the management of children

better than himself.

His favourite grandchild was a little boy who stood

third in the group of his grandchildren, a beautiful and

intelligent child, who bore from a very tender age a remarkable

resemblance to his grandfather. Toys or trifles were never given to

these children, but many wise words, and such sound advice as will never

leave their minds, but, along with recollections of many playful devices

for amusement, take part in their memories. There was a small copy of

Milton that was in constant use; it was a little, thick book, rather

tattered. It had been exposed during a fishing excursion to

vicissitudes, such as might happen to anything contained in the

coat-pockets of one who always waded without much thought as to whether

the water reached above the ankles or waist. Milton had been soaked, yet

this particular Milton was beyond price, and went with Professor Wilson

and this grandchild by the name of "Dumpy." It was never lost or

mislaid, for if the one did not know where it was the other did—was

certain of its whereabout, and so it lay between them. One day this

child had been walking in Edinburgh with his grandfather—a hot summer

day. The old man, feeling somewhat fatigued and overcome from heat,

proposed they should rest a while. The nearest point of repose was the

projecting base of George the Fourth's statue, at the head of Hanover

Street. Perfectly indifferent to the passers-by, or to any remark so

novel a position might call forth, the companions sat down—the stately

man, and pretty, long brown-locked boy. While they rested, no time was

to be lost—instruction and delight took the place of idle gazing—inert

dolce far niente had no meaning there.

"Dumpy" was at hand —passages were read aloud and explained. It is

doubtful if Milton was ever read before in the thoroughfare of a great

town, with no other auditor than a little boy.

The year that brought him the great grief of his

life, by laying his wife in her grave, kept alive every association of

sorrow, in imposing upon him a duty, which his benevolent nature readily

accepted. An old and faithful servant, who for many years had come and

gone in his household, finally came to reside with his family, in order

to be carefully nursed, as she was pronounced to be dying of

consumption. At that time Professor Wilson had gone to the country for

change of air and scene, hoping to find some benefit near the beautiful

woods of Hawthornden. He hailed with delight the idea that a sojourn in

that salubrious neighbourhood would be beneficial to the poor invalid

who had come to be taken charge of by his daughters. His interest in her

case was very great. Everything that kindness could suggest was done. As

long as she was able to walk, he would go with her to the garden or

avenue of the house, amusing her, and consoling her with cheerful words.

It soon happened

that she became worse, and lingered for some months in great suffering.

During that time, nothing could exceed the sympathy and tenderness shewn

her, to devise comfort for her at night, in order to shorten those

dreary watches that too often, alas! visit the dying who have no earthly

friends near, to give a word of comfort, or raise a cup of water to

their parched lips. This poor sufferer was saved such desolation. Night

after night Professor Wilson arose from his bed to see if he could do

anything to mitigate the pain, or make the weary pillow less hard.

Fainting-fits used to seize the invalid suddenly, and if alone her

distress was very great. To be made aware of the approach of these

attacks, he gave her a whistle which he always wore hanging from a

button on his coat, in order to call his dogs, when inclined to ramble

too far among fields, and trespass on proscribed ground. This

whistle—which he laid each night upon a table by her bedside—was the

signal that should call him to her assistance. Many a time the shrill

sound fell upon his ear; he was ever ready to hear it, even through the

long passage that separated his room from the part of the house where

she lay. He never left her till the fit passed off, and always called

some one to attend after he returned to his room. When she died, he

followed her to the grave, and shewed her memory the respect that was

due to a faithful and trustworthy servant.

A nature so kind and a heart so disinterested readily

won the respect and affection of dependants. Servants grew old in his

service, and became so attached, that even when no longer required, they

were unwilling to leave him.

The reaction of faithful love from a servant to his

master, finds a touching example in the conduct to Professor Wilson of

one who, for the long period of thirty-six years, considered himself

bound by contract with his own heart to serve, honour, and obey him,

even after his services had been during a considerable period dispensed

with ; but • nothing could make this warmly attached creature separate

himself from the interests of his master, for such he considered him

until the hour he died. The early part of Professor Wilson's life was

spent at the lakes of Westmoreland. Upon the banks of one of the most

beautiful, he chose his residence. And the tourist who now visits the

lovely Lake of Winandermere, seeks as an object of interest the once

dwelling-place of Wilson—Elleray, that "terrestrial paradise," so dear

to the poet's heart, not less on account of its unsurpassed beauty, than

its having been the home to which he first led the wife of his

youth—where with her he lived, until circumstances in his own position

made it imperative for him to leave that cherished place, and all its

associations of care and hope, to seek in the world a success that would

bring him independence and comfort. Faults not his own had deprived him

of a handsome fortune. A life of labour was henceforth to be his—the

fruits of which he has left to posterity.

Boating was his favourite amusement, and while in

Westmoreland, he had quite a little fleet upon Windermere. Among

his boatmen

there was one

who was a great favourite—known only by the familar appellation

of "Billy." This man, from the hour he first became an inmate at Elleray,

never looked upon any other place as his home, or any other man as a

master than Professor Wilson. He came with him to Scotland, and acted as

domestic servant. Poor Billy was charming, full of character and talent.

Alter a time he married, and with his Scottish wife he returned to

pretty Bowness, a little village that skirted Lake Windermere, not far

from beloved Elleray, and where Billy again resumed his calling as

boatman. However, after a while, Professor Wilson went annually with his

family to Elleray, and Billy, wherever he might be, in service or out of

it made no matter, was sure to find his way to Elleray, where he took up

his abode as long as the master of his affection remained there, without

any regard to the duties incumbent upon him as the servant of another.

It was an understood thing with Billy's conscience, that his original

master was in reality his only one, whether bound to him by the laws of

bondage or not. Many a happy summer passed on, and this kind creature's

attachment seemed to become stronger and stronger. At last, in the

course of time, the yearly family visits to Elleray ceased—the place was

let. Billy was nearly brokenhearted ; but the clouds cleared off—the

sunshine of his life once more brightened the horizon. One season,

having been hired by a gentleman as his boatman, he accidentally heard

from him that Professor Wilson was to be in the country, in the course

of a day or two. Joyful intelligence!— Billy was off next day, and

arrived at Elleray. There he found the realisation of the good news. He

did not return to the gentleman's service that summer. So well-known was

the adoration he bore his old master, that no one ever interfered with

any arrangement he might make, while the loadstar of attraction was

near. Time again breaks the chain, but Billy is never lost sight of.

Professor Wilson looks kindly after his interest, and saved him from

poverty and distress. To Elleray he often went, and lingered about the

haunts of his master. On one occasion, some wood was to be cut down

there for sale. The smaller sort, set apart tied in little bundles,

might be bought separate. The day of the sale found Billy there. Lot

after lot was sold; he too must have his share; his offering was small,

but it was enough to get what he desired. In the after part of the day,

Billy was seen sitting weeping upon his little heap of wood, which with

a heavy heart he carried to his cottage, where it was laid aside in a

place of safety. It was his master's wood— could he burn it? No, not for

worlds! To see his master once more, still continued the uppermost

thought in his heart. And so to Edinburgh he went, and never again left

it, but remained an inmate of Professor Wilson's house for several

years, doing any little work which his enfeebled body was able for, and

very frequently acting as nurse to the merry race of grandchildren, he

was so proud to tell stories to, of that wonderful man who, at his

hands, came forth burnished with all the lustre and valour of a "Sir

Lancelot de Sac." At last poor Billy fell sick, and grew weaker day by

day; his devoted love found ample return, in kind and unwearied

attention from the master he served so faithfully. The evening he died,

Professor Wilson walked from his house in town into the country, where

his poor old servant, a short time before, had been removed in order to

get some change of air. His wife had been sent for from Westmoreland.

She came to attend him in his last hours, which gently and peacefully

were brought to a close. The old man, pale and worn, with weak and

fading eye, sought to rest it to the very last upon his master's face,

whose hand was clasped in his, while for more than an hour, he sat

watching the departing breath. When the last sigh was given, and silence

had set its eternal seal over the mortal remains of his single-hearted

and humble friend, Professor Wilson rose from the side of the bed, where

he had sat, with a solemn and sad countenance, stood for a moment or two

gazing at the wasted form of his faithful old servant; then, stooping

down, he kissed, with tender remembrance of so true a nature, the damp

forehead of the dead man. "Poor fellow, he is gone, and we are all going

too. I shall lay his head in the grave, in some quiet, green spot,

pleasant to the memory." He was buried in the beautiful Warriston

Cemetery, in the outskirts of the town.