|

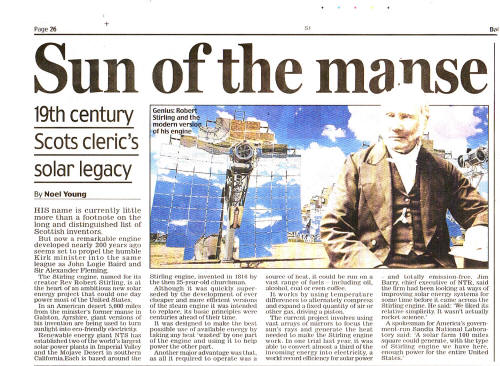

Robert Stirling, inventor of the Stirling

engine, was born at Gloag, Methvin, Perthshire on 25 October, 1790 and was

the third of a family of eight children. His father was Patrick Stirling,

son of Michael Stirling of Threshing Machine fame and his mother was Agnes

Stirling, daughter of Robert Stirling, farmer in the Cromlix, Dunblane.

In 1850 the simple and elegant dynamics of

the engine were first explained by Professor McQuorne Rankine.

Approximately one hundred years later, the term "Stirling

engines" was coined by Rolf Meijer in order to describe all types of

closed cycle regenerative gas engines. Perhaps his most important

invention was the "regenerator" or "economizer" as he

called it. This is used today in Stirling engines and many other

industrial processes to save heat and make industry more efficient.

Stirling engines are unique heat engines

because their theoretical efficiency is nearly equal to their theoretical

maximum efficiency, known as the Carnot Cycle efficiency. Stirling engines

are powered by the expansion of a gas when heated, followed by the

compression of the gas when cooled. The Stirling engine contains a fixed

amount of gas which is transferred back and forth between a

"cold" end (often room temperature) and a "hot" end

(often heated by a kerosene or alcohol burner). The "displacer

piston" moves the gas between the two ends and the "power

piston" changes the internal volume as the gas expands and contracts.

Stirling engines are being studied at NASA

for use in powering space vehicles with solar energy!

Robert was a bright lad and, from 1805 to

1808, attended Edinburgh University, where he studied Latin, Greek, Logic,

Mathematics and Law. His younger brother James was later to attend at the

age of 14 and became a Civil Engineer of some fame.

Robert enrolled as a student of Divinity at

Glasgow University in November 1809 and completed five sessions. He was a

model student there. On 15th November 1814, he was enrolled at Edinburgh

University as a Student of Divinity, where again his conduct was

exemplary. In 1815, Robert Stirling was examined by the Presbytery of

Dunbarton and, after the usual tests, found competent to preach the

Gospel, a license being issued to this effect on 26th March, 1816. In

1816, he was presented by the Commisioners of the Duke of Portland to the

second charge of the Laigh Kirk, Kilmarnock. He

appeared before the Presbytery of Irvine, who unanimously agreed on his

suitability and, after satisfactory execution of varied trials had him

ordained Minister of the Second Charge of Laigh Kirk on 19 September,

1816.

At an early age, Robert had been introduced

to engineering by his father, Patrick Stirling, who had assisted his own

father, Michael, in the maintenance of his threshing machines, and had

always shown a keen interest in anything mechanical, and in particular in

sources of power for machinery. On 27th September, 1816, he applied for a

patent for his now well famed engine. He had his patent enrolled on 20 Jan

1817. He had been working on this engine for several years before moving

to Kilmarnock, and his research continued there.

In Kilmarnock, he met up with a certain

Thomas Morton, with similar interests in new ideas. He was the son of a

brick manufacturer, who had served an apprenticeship as a turner and

wheelwright, and then set up in this business on his own account. He was

responsible for several innovations including a new improved carpet loom.

He also erected a novel observatory at Morton place, in the year 1818.

When the two men got together, Rev. Robert

arranged with Morton for the use of premises at Morton Place, where his

experiments continued. These were specially built for them. Stirling was

to use them for some 20 years. His experiments embraced more than the

Stirling Heat Engine. He was, like Morton, also interested in astronomy

and was not long in acquiring the skills which Morton could give him in

the manufacture of lenses. His brother James closely followed the

experiments and encouraged

his brother greatly in his research.

Robert Stirling was married, on 10 Jul

1819, to Jean Rankin, daughter of William Rankin, wine merchant in

Kilmarnock, and Jean McKay. She was born at Kilmarnock on 27 Jun 1800.

Their family turned out to be as inclined to engineering as the father.

Patrick Stirling, born 29 Jun 1820, became

a famous Railway Locomotive Engineer.

Jane Stirling, born 25 Sep 1821, fed ideas of her own to her bothers.

William Stirling born 14 Nov 1822, was a Civil Engineer and Railway

Engineer in South America. Robert Stirling, born 16 Dec 1824, was a

Railway Engineer in Peru.

David Stirling, born 12 Oct 1828, followed in his father's footsteps and

became the Minister of Craigie, Ayrshire.

James Stirling, born 02 Oct 1835, was another well known Railway Engineer.

Agnes Stirling, born 22 Jul 1838, was a gifted artist whose talents were

confined to the family.

Robert Stirling was a gifted speaker and

was beloved by his flock. He died at Galston on 06 Jun 1878, leaving a

heritage in his engine which has yet to see its full potential.

Click

here to see a Stirling engine that runs of a cup of coffee

From the book "Stirling Cycle

Engines" by Andy Ross

Everywhere, it seems, interest is

picking up in the Stirling engine. The prestigious Jet Propulsion Lab

recently reported that the Stirling is one of the two most promising

alternative automobile engines for the future, offering silence, long life,

improved mileage, and greatly reduced pollution. Ford Motor Company

announced it has installed an experimental Stirling in a sedan for testing

as part of its current research effort on the Stirling. The Energy Research

and Development Administration recently entered an eight year $110 million

contract with Ford for development of a Stirling automobile engine. In

Sweden, work is said to be progressing very well toward the development of a

Stirling suitable for delivery vans and other vehicles.

By no means is all of the current

interest in this old engine related to powering road vehicles. In Athens,

Ohio a great deal of development work is being done on a Stirling powered

heat pump for home heating. In this application, gas or other fuel is used

to run a small Stirling engine, which in turn drives a conventional heat

pump to heat or cool a home. This may seem like a complicated way to provide

heat when compared with the conventional method of simply burning the gas

and using that heat directly. But the fact is that the Stirling heat pump

approach provides a great deal more heating for the same amount of gas,

because it makes a more efficient use of the high temperature flame of the

gas. Even at today’s gas prices, it is anticipated that such devices could

pay for themselves in gas bill savings in three or four years.

In Holland, where the revival of

interest in the Stirling engine first began about forty years ago, air

liquifying machines based on the Stirling cycle are being produced and sold

world-wide.

In India, South America, and other

places around the world, the Stirling is receiving attention as a potential

power source for pumping irrigation water and doing other farm chores;

because, unlike the gasoline engine, it can use almost any combustible

substance for fuel, including sticks and straw. As the price of oil

continues to rise, the multifuel capacity of the Stirling becomes one of its

most important virtues.

Nor is all the current interest in the Stirling solely

for utilitarian purposes; hobbyist Norris Bomford spent several years

developing a Stirling engine to propel his graceful rowing skiff over the

lakes and rivers of England. The engine, which pushes his craft at a gentle

three to four miles per hour, is so quiet that builder Bomford can indulge

in his two favorite recreations at the same time — boating and listening to

classical music on a portable record player.

Many other hobbyists in England and

North America have discovered for themselves the intriguing challenges

presented by designing and building their own small Stirling engines. The

first international power competition for these model engines has been held

in London, under the auspices of the well-known Model Engineer

magazine, and it promises to become an annual event.

What is a Stirling?

What is a Stirling engine? Like the

gasoline, diesel, and jet engines with which we are all familiar, the

Stirling is a heat engine; that is, an engine that derives its power from

heat. But unlike those other engines, the Stirling obtains its heat from

outside, rather than inside, the working cylinders. In this respect, the

Stirling is similar to that charming old workhorse of the industrial

revolution, the steam engine.

This difference, between external and

internal combustion, is one of the main reasons for the widespread current

interest in the Stirling. An internal combustion engine, that is an engine

that burns its fuel inside its working cylinders or chambers like the

gasoline, diesel, or gas turbine engine, is generally rather particular

about its fuel. A gasoline engine may be modified to run on hydrogen,

methane, or propane; but it will not run on salad oil, straw, coal, or peat.

When one thinks of a small gasoline engine, one tends to think of it as a

self-contained little powerpak; perhaps it would be more appropriate to

think of it as a power plant with an oil refinery attached to it!

Of the three internal combustion

engines mentioned, the gas turbine is probably the most omnivorous with

respect to fuel; yet even it is limited indeed when compared to the

Stirling. Quite literally, any source of heat, as long as its temperature is

high enough, will do to power a Stirling. This last statement is no doubt

true of any other externally heated engine, like the steam engine, but

interest has focused on the Stirling as the externally heated engine of

choice because it holds the promise of making the most power for a given

supply of heat (or fuel) of the practical alternatives presently known.

Thus, the Stirling can directly use

concentrated solar energy, or it can burn kerosene, coal, straw, wood,

sawdust, cardboard, discarded Christmas trees, or any other combustible

substance imaginable.

It can also use stored heat. Certain

salts give off great amounts of heat for their weight in the process of

cooling from their liquid to their solid state. With a salt such a lithium

fluoride, this change of state occurs at a high temperature, in the

neighborhood of 1550°F, which is an excellent temperature for the hot end of

a Stirling engine. When space-age techniques of thermal insulation are

employed in conjunction with these salts, it has been found that a very good

thermal storage battery can be made from which to run a Stirling engine.

This is similar to the electric motor-storage battery system, except heat is

stored instead of electricity. The thermal battery-Stirling system is

superior, however, in that it can be recharged (electrically reheated) much

faster and it can store over eight times more shaft power per pound than a

lead-acid battery.

But even when it is burning a

conventional fuel, such as gasoline or diesel fuel, a Stirling has an

important advantage resulting from its basic design. That is, its combustion

takes place against hot surroundings at atmospheric pressure, and not

against cooled cylinder walls at elevated pressures as is the case in the

gasoline engine. Combustion under the conditions in the Stirling produces

practically no carbon monoxide or unburned hydrocarbons, and the level of

nitrogen oxides is also relatively low. In terms of these three pollutants,

the Stirling is about the cleanest heat engine imaginable, and this accounts

for the present interest in the engine by automakers.

|