|

Ancient, customary, and common law Celtic law of succession Celtic

marriages No general change of law AEstimatio personarum Ancient

law of compensation Criminal law Wager of battle Compurgators

Trial by battle Trial by fire and water Law of ordeal Proof by

witnesses gradually admitted Penalties of theft Penalty of slaughter

Four pleas of the Crown Laws of Galloway Galloway customs Law of

sanctuary Church girth Famous sanctuaries Stow in Wedale

Lesmahago Inverlethan Tyningham.

It requires no evidence to

convince us that there existed a system of law in Scotland, before the

great revolution in the dynasty and institutions of the country that

followed the death of Macbeth. Wherever society exists, life and the

person must be protected. Wherever there is property, there must be rules

for its preservation and transmission. Accordingly, in the most ancient

vestiges of the written law of Scotland, we find references to a still

earlier common law, Assiza terras the law of the land lex Scotiae

evidently of definite provisions and received authority.

It has been very

confidently asserted that in Scotland we have not, and never had any

Common Law. To answer that monstrous proposition, I need only call your

attention to the law of primogeniture. It is certainly no act of

Parliament, or ancient ordinance before Parliamentary times, or adoption

from the Roman code, to which we owe this foundation of our heritable

rights. What excludes sisters from the succession in heritage, whilst they

have it in moveables? What gave representation in land from the earliest

times, whilst we have only last year adopted it in personal succession?

Certainly no written law that can be pointed out in our statute book.

If the assertion had been

that there was nothing or but little of local and peculiar in our common

law, it might be assented to with less difficulty. I believe Scotland, at

the different eras of her history, used the laws of the people cognate to

her then dominant race. Whilst under a Celtic sway, her laws were those

which have received a certain shape and definiteness, from their longer

use and greater cultivation in Ireland; and her customs (the most

important part of law) were those maintained in the wilds of Galloway, as

long as the Celtic language prevailed there; and which are only now

disappearing among the patriarchal tribes of the Highlands. You will not

expect me to prove this proposition, which is in itself so likely that it

seems to throw the burden of proof upon the controverter of it. The only

facts we have, capable of historical record, to prove the existence of a

peculiar Celtic law in Scotland, are connected with the institutions of

succession and marriage.

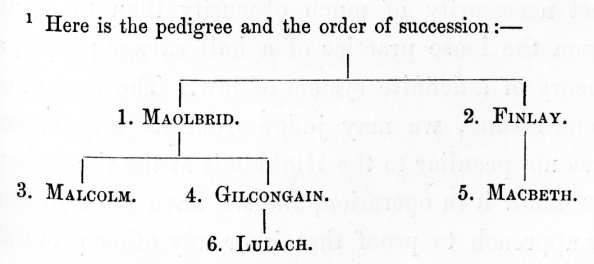

The law of succession was

according to the law which is called, in Ireland at least, the law of

Tanistry a system which depended upon a descent from a common ancestor,

but which selected the man come to years fit for war and council, instead

of the infant son or grandson of the last chief, to manage the affairs of

the tribe, and who was recognised as the successor, under the name of

Tanist, even during the life of the chief. To take one instance, from the

ancient history of Moray, a district which long continued to pay respect

to its ancestral Maormors. Maolbride is the first known Maormor; he left a

son Malcolm, but the office or dignity did not descend upon him, but went

to Finlay the brother of Maolbride. After Finlay's death, Malcolm at

length succeeded to his father's place ; he was succeeded in turn by his

brother Gil-congain. Gilcongain was succeeded by Macbeth, the son of

Finlay; and after Macbeth had lost his local dignity and his crown with

his life, he was succeeded in the maormorship by Lulach, the son of

Gilcongain; the maormorship thus passing, in as many generations, to the

brother, nephew, brother, nephew, and cousin-german.

In the competition for the

crown of Scotland [. between Bruce and Balliol, where no art of the most

dexterous advocate was omitted, Bruce pleaded that as nearer in degree, he

should exclude the representative of the elder line; and to illustrate

this, he alleged that anciently, in the succession to the king-dom of

Scotland, the brother was wont to be preferred to the son of the deceased

king; and he cited a number of instances in which this took place.

Balliol, while he denied the inference, did not question the truth of the

examples; but he alleged that the son, and not the brother, was the

nearest in degree. Lord Hailes remarks upon this argument, "Here Balliol

attempted to answer Bruce's argument without understanding it. Bruce

supposed an ancestor to be the common stock, and the degrees to be the

persons descending from that stock. Hence the king's brother stood in one

degree nearer the common stock than the king's son."

I have said that the law of

marriage was viewed as one of the peculiarities of the Celtic race, but

there is nothing more likely to mislead us in a subject necessarily of

much obscurity than to found upon the loose practice of a half savage

people, a theory of a definite system of law. The system of hand-fasting,

we may judge from its very name, was not peculiar to the Highlands at the

time when we know it in operation, and we have no evidence or approach to

proof that it or any other peculiar customs of marriage were recognised in

Celtic Scotland after the introduction of Christianity had given one rule

of marriage and legitimacy to the whole Christian world (unless we are

obliged to except England).

When the Anglicising policy

of the descendants of Malcolm Canmore had everywhere throughout Scotland

thrust aside the ancient race, the institutions and laws of Saxon England

rapidly spread over our country. There are some indications, however, that

on the whole these were not much opposed to the old usages of the old

people. Let it be remembered that that was a peaceful revolution, at least

not effected by open war or conquest. If there had been any fundamental

change introduced in the rights or laws of the people, it must have given

rise, if not to disputes, at least to a general expression of resentment

amongst the parties suffering by the change (for all changes of law

produce suffering to some party), but in the recorded transactions and

chronicles of that time we do not find a trace of any violent or general

alteration of law, except in the matter of succession, which I have

already alluded to; a change which ought in fact to be treated as part of

the great feudal system then introduced, and spreading rapidly over all

Britain.

At the earliest period,

then, of which we have information of an authentic kind, the laws and

institutions of Scotland did not differ materially from those of the other

northern nations of Europe. Even that vestige of an earlier age which I

have' pointed to, the preference of the brother to the son in succession,

amongst the patriarchal clans, was, as I have already shown you, of

frequent occurrence in Saxon England, and we cannot doubt that it must

have taken place amongst all rude peoples, where the law was not yet

strong enough to support a young and untried heir.

The system of the

estimation or valuation of persons according to their class, and in

connection with it, the adoption of pecuniary penalties and compensation

for crimes, prevailed with us as with the other northern nations. We find

a price or value set upon every one according to his degree, and different

amounts of injury taxed with minute and affected precision.

In a fragment which I conceive to be the oldest written portion of the

laws of Scotland, and which was known and proscribed as barbarous by

Edward I. in 1305, we have some details of this system. The chapter is

called "The Laws of the Brets and Scots." Unfortunately, our earliest

version of it is in Norman French. The system of compensation prescribed

in it, commences at the top of society. The estimation, or appraising as

we should say in vulgar parlance, of the king of Scots, was a thousand

cows, or three thousand of the coin called ores, each of which was equal

to sixteen pennies. The king's son, or an earl, was estimated at seven

score cows and ten. An earl's son, or a thane, at a hundred cows. The son

of a thane, at sixty-six cows and two-thirds. The nephew of a thane, or an

oget-theyrn was estimated at forty-four cows, and 21 2/3d and, says the

law, all lower in the parentage are to be considered as villeins

translated in the Latin version "rustici" and in the Scotch, "carlis;" the

estimate of a villein was sixteen cows. The estimate of a married woman is

less by a third part than that of her husband. If unmarried, it is equal

to that of her brother.

The compensation prescribed

for drawing blood is graduated with equal minuteness: "The blude of the

hede of ane erl or of a kingis sone is ix ky. Item the blude of the sone

of ane erl or of a thayn is vi ky. Item the blude of the sone of a thayn

is iii ky. Item the blude of the nevo of a thayn is twa ky and twapert a

kow. Item the blude of a carl, a kow."

I have not troubled you

with the ancient Scotch terms applicable to these laws of compensation.

Some of them are more or less intelligible to the Celtic scholar; but I

cannot venture to speak of etymologies from that language, of which I am

entirely ignorant. There is no reason to doubt, from the similarity of the

laws, that the terms Cro, galnis, and enach, are nearly equivalent to the

Wers, wites, and Bots, of the old English law.

Among laws deriving their

remote origin from a society where the lands were not individual property,

but held in common, we should seek in vain for any early provisions

concerning the inheritance or the transmission of land. Transactions and

contracts were also unknown, or so simple that they had not yet required

the attention of the lawgiver. Hence the preponderance in those early

codes, of laws regarding crimes, over those more subtle distinctions which

the complicated relations of commerce demand. Our oldest laws are full of

provisions regarding the proof and punishment of theft and murder. The

murderer taken red-hand (layun-darg in Gaelic), or the thief caught with

the fang or bak-berand or hand-habend, was "justified," we may believe,

without any unnecessary and inconvenient delays of process. It was where

the matter was not quite so plain; where an accusation was brought and

denied, that the peculiarities, as we consider them, of the old law

appear. If we may trust to the eras of our published laws, it would seem

that in the reign of David I., a man accused of theft might clear himself,

either by doing battle, or by the purgation of twelve leal men.

[Gif ony appelis ony man in

the Kingis court or in ony othir court of thyft it sall be in the lykyng

of hym as beis appelyt, quhether he wil bataile or to tak purgacioun of

xii leil men with clengying of a hyrdman.]

You will observe that there

is nothing here said of the evidence of witnesses on either side. By our

old law, indeed, little use was made of that kind of evidence. If the

accused denied, he did not call witnesses cognisant of the facts; but was

bound to find compurgators to swear for him, that they believed him

guiltless men of the vicinage, and knowing the character of the parties

accusing and accused.

The number of compurgators,

which varied from one to thirty, seems to have been determined by the

nature of the crime and the characters both of the accuser and the

accused. When goods were stolen from the poor and weak, who had no help of

man, but were under the king's protection, if one man swore upon the holy

altar, as the use was in Scotland, and before worthy witnesses, that he

knew the thief, and named him, the individual so accused was bound to

restore the goods if he could not establish his innocence.

If it could be proved by

two "leil" men that an individual had violated the king's peace in gyrth,

he was at once punished according to the nature of his crime.

In William's reign, if a

man habit and repute a thief was pursued by the suit of one barony and

could find no borch, he was hanged.

Twenty-four leil men were

necessary to "clenge a man anent the king," and if he was "appealed" of

felony or of life or limb, the compurgators must be found in the

sheriffdom where the crime was perpetrated. If a priest was adduced in

warrant for theft, and declared that the thing challenged was reared by

himself, he was bound to prove that by the oaths of three worthy men

approved by the lords of the town. A lord, from whose prison a thief had

escaped, was obliged to clear himself of being accessory to the theft's

escape by twenty-seven men and three thanes.

In the case of burgesses

the law of acquittance was a little different. If a burgess was prosecuted

by the provost for breaking of assize, and in complaints between an

uplandman and a burgess that might be settled by oath, the law prescribed

"clenging by six hand." If a burgess was challenged for theft by an

uplandman, or if he was challenged to do battle after the age of fighting,

he was to clenge him by the oath of twelve of the neighbourhood. A man

accused of theft might choose purgation of twelve leil men with clenging

of a hyrdman," or to do battle.

When there was as yet no

trust reposed in the evidence of witnesses, if the accused or the defender

failed in bringing his sufficient band of compurgators, his last resource

was in the "judicium Dei," where the theory of the law trusted to the

direct intervention of the Deity to decide the rights of parties. The

first and most usual mode of this appeal was the judicial combat, or wager

of battle; and solemn laws and rules were made for its mode of procedure;

and courts and reverend churchmen and judges and monarchs sat to witness

the combat, where the strong man overcame the weak and still forced

themselves to believe that God decided the cause.

In the earliest of our

laws, restrictions were introduced in the application of trial by battle.

Churchmen were specially exempted from it, which had not always been the

case; and men above sixty might decline the combat. Burgesses had

privileges with regard to it. The burgesses of king's burghs might claim

combat against those of burghs dependent on subjects, but could not in

their turn be obliged to grant them the combat. Knights and free tenants

might do battle by proxy. Those of foul kin were bound to fight in person.

After the judgment was

pronounced ordaining trial by battle, or by the other ordeals of

fire or water, it was no longer open to compound the cause for a penalty;

and any lord of a court lending himself to such a transaction forfeited

his court.

During the judicial combat

the strictest silence was preserved. The judges of Galloway enacted, that

he who should speak in the place where battle was waged, after silence was

proclaimed, should forfeit ten cows to the king; and that if any one

should interfere with his hand, even to the extent of making a signal, he

should be in the king's "mer-eiament of lyf and lym."

Among the common privileges

and prerogatives of jurisdiction granted to the greater monasteries, was a

right of trial by fire and water. The earliest charter of the abbey of

Scone by Alexander I. (and we have few earlier in Scotland), confers such

a jurisdiction, and I believe the place in which the actual ordeal was

held, was the little island in Tay, which lies midway between the abbey

and the bridge of Perth. We find nowhere the details of the application of

the ordeal of hot iron in Scotland. It was considered as somewhat the more

honourable of the two; and by the laws of England, parties declining

combat by reason of age or maiming, were to purge themselves by hot iron,

if free men, and by the ordeal of water, if of servile rank. This last

among other barbarities was revived when, to the disgrace of humanity and

of an age that called itself c civilized, our courts of justice were

occupied with the discovery and punishment of witches. I do not know if

the results then are to be taken as any test of the old system of trial

and torture. In many instances the poor wretches, persecuted to madness,

not only admitted the whole of the charge against them, but went beyond

what the imaginations of their accusers could conceive, and disclosed

hellish mysteries and impossible horrors as taking place in their own

presence or in their own persons.

David I. saw the abuses to

which such a system of trial was liable, and, in one instance, he provided

that his own judge should always be present in the court of the Abbot of

Dunfermline, to see that justice was duly administered. It is extremely

probable that he passed a general law to the same effect, though it has

not been preserved to us. In 1180 a statute of William the Lion enacted,

that "na baron have leyff to hald court of lyf and lym, as of jugement of

bataile or of watir, or of het yrn, bot gif the scheriff or his serjand be

thereat, to see gif justice be truly kepit thar, as it aw to be."

But all ordeals were

falling into disrepute at the earliest time when we can mark our law in

operation. A statute of King William enacted, that if one were accused by

a certain number of persons of repute, he should underlie the ordeal of

water; but if, in addition to those accusers, three witnesses could "be

found to speak to the fact, he was not to undergo the ordeal, either of

fire or water, "but hastily to be hangit." [Quha sa ever efter lentyrn

nixt efter the deliverans of oure Lord the King be chalangit of thyft or

that he has gevin thyft-bote and that may be tayntit on hym be the greyff

of the towne and thre othir lele men he sale be tane and underly the law

of wattir. And gif forsuth anent the samyn thar may be witnessing of thre

lele men of eld to-gidder with the forsaid witness thruch na batal sal he

pas na to wattir na yet to yrn bot hastily he sal be hangit. Alsua leffull

it is to na man to take redemp-cion for thyft efter dome gevyn of wattir

or of batal.Assize R. Willelmi, a.d. 1181.]

In 1230 a statute of

Alexander II. was passed which has been twisted ingeniously in some of our

old law manuscripts, to import an entire abolition of the ordeals of fire

and water. [The King Alysandir has statut that gif ony man chalangis ony

othir man of thyft or of reyflake & the defendour wil put him on a gud &

leil assise & the assise sal mak him clene quhit sal he be & the followar

sal be in the amercyment of the King or of the Erl or of the baron gif it

be of thyft. And gif the defendour be foul thar sal be done on hym

rychtuis dome. And it is to wyt that fra this tym furth thar sal be no

jugement done (on him) thruch dykpot na yrn.Star tuta R. Alexandri II.,

a.d. 1230.]

The title given to this law

in the Ayr MS. is, "Deletio legis fosse et ferri et institutio visneti,"

and it supports that title by a curious misreading of the law. The statute

of Alexander only gave the accused the choice of putting himself upon an

assize, and declared, that one who has already been acquitted by an assize

shall not for the same offence be required to undergo the ordeals. When

judgment by assize or jury was introduced we cannot tell, nor when the

custom of ordeal was abolished. The laws I have quoted to you seem to mark

it in a state of transition. In certain civil causes of the greatest

importance, the proof, even in the time of David, was by an assize of

twelve good men (assisa bonce patrice). That took place in pleadings under

brieves of mortancestry and novel diseisin. [It is statut that breiffis of

Mortancestre & new dyssesing neirr mair sal be impleydit be challange of

the party askand hot allanerly be an assyse of the gud cuntre & nane othir

ways, and na challangis lyis thar to for quhi tha xii the quhilkis ar

chosyn of the gud men of the cuntre till an assise sal say allanerly thar

entent and thar veredyk eftir the poyntis and the artikyllis of bayth the

breiffis and eftir that as that assyse pronouncis in veredyk rycht sa that

dome sal be geyffin to the partiis.Assize R. David, 35.] At least as

early, the Church courts of Scotland were in the use of taking and

recording in writing the evidence of witnesses; and assizes of sworn men

were used as the rude machinery for trying other civil causes. It would

set at defiance all our notions of the sense of men, and the value of

experience, if any country, having in some points admitted proof by

witnesses, could long have adhered to a settlement of questions the most

important to mankind, by the ordeals of fire or water, or still more to

that law which really declared the strong hand to be always in the right.

The penalties of theft were

not with us so heavy as in England; but the compounding of theft or

protection of a thief were very carefully guarded against. By the ancient

law of Berthynsak, summary procedure was established with a thief caught

with his burden, such as a sheep or a calf, but you will observe there was

there no capital punishment. [Of byrthynsak that is to say of the thyft of

a calf or of a ram or how mekil as a man may ber on his bak thar is no

court to be haldyn bot he that is lord of the land quhar the theyff is

tane on swilk maner sall haf the scheip or the calf to the forfalt. And

the theiff aw to be weil dungen or hys er to be schorn. And that to be

done thar sal be gotten twa lele men. Na man aw to be hingit for les price

than for twa scheip of the quhilkis ilkane is worth xvi d.Assize R.

Willelmi,]

Another statute of

undoubted antiquity, although its precise date cannot be fixed, prescribes

the gradations of punishment for different degrees of theft. [Giff ony be

tane with the laff of a halpenny in brugh he aw throu the toun to be

dungyn. And fra a halpenny vorth to iiij. penijs he aw to be mare sairly

dungyn. And for a payr of shone of iiij. penijs he aw to be put on the cuk

stull and eftir that led to the bed of the toune, & thar he sal forsuer

the toune. And fra iiij. penijs til viij. penijs & a ferthing he sal be

put upon the cuk stull and eftir that led to the hed of the toune and thar

he at tuk hym aw to cut his eyr of. And fra viij. penijs and a ferthing to

xvi. penijs and an obolus he sal be set upone the cuk stull and eftir that

led to the hed of the toune and ther he at tuk hym aw to cut his othir ear

of. And efter that gif he be tane with viij penijs and a ferding he that

takis him sal hing him. Item for xxxij penijs. j obolus he that takis a

man may hing him. Fragmenta Collecta 42.]

If a thief took refuge in "Gyrth,"

or sanctuary, he could lose neither life nor limb, but enjoyed the king's

peace. Nevertheless, he was bound to restore as much as he stole; to make

amends to the king according to the law, and to swear on the holy relics

or the book of the Evangel, "that fra that time furthwartis, never mair he

sal do reyflake na thyft."

While, as I mentioned, a

value was set upon every man, and by that rule, a fine could be imposed

for injury done to his person, and much more for his slaughter, at the

same time, undoubtedly the legal and strict punishment of murder was

death. We cannot discover from the imperfect relics of our ancient code of

customary law, how this seeming inconsistency was reconciled. It is at

least exceedingly probable that it lay with the kindred and friends of the

murdered man to abstain from prosecuting to the utmost those accused of

his death, where their feelings of indignation and vengeance could be

solaced with a pecuniary compensation. The law had not yet pervaded all

society; and public justice was scarcely separated in men's minds from

private revenge.

It was not the estimation

of the person alone that, by those old laws, ruled the amount of the

penalty for slaughter. That, indeed, was the assythment paid to the

kindred of the slaughtered man, but another penalty was due if the peace

of the king or other lord had been violated by the shedding of his blood.

The person guilty of the slaughter of a man within a place where the

king's peace was proclaimed, forfeited nine score cows. The manslayer

within the peace of an earl or king's son, incurred a forfeit of four

score and ten cows; and so progressively in the lower degrees of rank.

It was no doubt with a

laudable intention that the sovereign, in the profuse distribution of

rights of jurisdiction to subjects in Scotland, reserved what were long

called the four pleas of the Crown murder, rape, fire-raising, and

robbery. It was intended that at least those great crimes and their

punishment should be removed in some degree from private influence. At a

later time, and under a different system of penalties, it became a point

of economical policy to preserve for the impoverished Crown a jurisdiction

which afforded so large an income, by the fines and escheats of the

justiciar's court.

There was only one province

of the Scotch king's dominions that we find asserting peculiar customary

laws. We know little of the early history of the district now called

Galloway. It had scarcely come under the confirmed dominion of the kings

of Scotland in the reign of Malcolm Canmore. We have seen the rude

insubordination of its people, under his son David at the Battle of the

Standard. The native lords were still too powerful for the distant

authority of the sovereign. William the Lion had a code of laws for its

government (assisa mea de Galweia), and judges for administering them.

They met at several places, and we have still records of a few of their

decisions, some of which are remarkable. [At Dumfries it was iugit be the

iugis of Galoway that gif ony Galoway man be convickyt ouder be batal or

be ony other way of the kingis pece brokin the king sal haf of hym xij**

ky and iii gatharionis or for ilk gatharion ix ky the quhilk ar in numer

xxx and vij. Na Galoway man aw to haf visnet but gif he refuse the law of

Galoway and ask visnet. Item thar the samyn day be the samyn iuges it was

iugit that gif ony in the palice quhar that batal is wagit quhair pece

sulde be haldin hapins for to spek outan thaim that ar to keip the palice

the king sal haf of hym x ky in forfalt. And gif ony man puttis his hand

to or makys a takyn with his hand he sal be in the kingis merciament of

lyf and.lym. Assize R. Willelmi.] Among other places, the judges of

Galloway are found at Lanark prescribing rules to the Mairs of the

province regarding the mode of collecting the King's kane.

For long after that time,

Galloway continued to be governed according to its own peculiar laws. In :

the reign of Robert Bruce, its people had not yet acquired, nor perhaps

desired, the right of trial by jury, but practised the mode of purgation

and acquittance according to their ancient laws those very laws of the

Brets and Scots which Edward in vain endeavoured to abolish. As late as

1385, Archibald Douglas, lord of Galloway, while undertaking in Parliament

to further the execution of justice within his territory, protested for

the liberty of the law of Galloway in all points.

At a time when the

punishment of crime, and the compensation even for accidental damage,

depended on the feelings or caprice of individuals, it was the highest

humanity to interpose between the wretch fleeing from vengeance and

justice, and his pursuer armed with the powers of the law, but stimulated

by private motives. And here the Church raised its arm in mercy. It had,

indeed, from the earliest time of Christianity, been held sacrilege to

violate a church with bloodshed; but it was a subsequent invention to

proclaim for it a right of sanctuary ; to declare that persons fleeing to

the Church, or to certain boundaries surrounding it, should for a time at

least, and under certain conditions, be safe from all persecution. Much

doubt has been expressed regarding the constitution and privileges of the

church sanctuaries of Scotland. Without going into the very curious

Teutonic antiquities of the subject, or speculating upon the times when

among our forefathers, as in Judaea of old, places of refuge were

anxiously provided " that the slayer may flee thither which killeth any

person unawares" "that the manslayer die not until he stand before the

congregation in judgment"I would observe, that by the canon, and the more

ancient ecclesiastical law, all churches were held to afford protection to

criminals for a limited period, sufficient to admit of a composition of

the offence, or, at any rate, to give time for the first heat of

resentment to pass over before the injured party could seek redress. In

several English churches there was a stone seat beside the altar, where

those fleeing to the peace of the Church were held guarded by all its

sanctity. One of these still remains at Beverley, another at Hexham. To

violate the protection of the frith-stol the seat of peace, or of the

fertrethe shrine of relics, behind the altar, was not, like other

offences, to be compensated by a pecuniary penalty : it was bot-leas,

beyond compensation. [There is an English notice of a breach of sanctuary

and its punishment by ecclesiastical authority in 1312. The bishop of

Durham heard with dismay that certain children of evil had incurred

excommunication by withdrawing from the church of the Carmelites of

Newcastle, some who had fled thither imploring church protection for the

safety of their lives; and afterwards, when the guilty person is

discovered, namely, Nicholas le Prorterhe is sentenced to appear

bare-headed and bare-foot, wearing only a linen robe, at the door of the

church of St. Nicholas of Newcastle, every Sunday for a whole year, and

there to be publicly scourged (fustigatus) by the curate, in presence of

the assembled congregation, and from thence scourged to the church of the

Carmelites, all the way confessing his fault. Moreover, he is to have the

same penance at the church of St. Nicholas and the cathedral church of

Durham, on three days of Whitsun week.]

That the Church thus

protected fugitives among ourselves, we learn from the ancient canons of

the Scotican councils; where, among the list of misdeeds against which the

Church enjoined excommunication, after the laying of violent hands upon

parents and priests, is denounced "the open taking of thieves out of the

protection of the Church." But though all were equally sacred by the

canon, it would seem that the superior sanctity of some churches, from the

relics presented there, or the reverence of their patron saints, afforded

a surer asylum, and thus attracted fugitives to their shrines rather than

to the altars of common parish churches. We must not be surprised that in

rough times even Holy Mother Church was not always able to afford

protection to her suppliants against the avenger of red-hand; and it was

to strengthen her authority, and to support what in the circumstances of

society was a salutary refuge against rash vengeance, that the Sovereign

at times granted his sanction to particular ecclesiastical asylums.

The most celebrated, and

probably the most ancient of these sanctuaries, was that of the church of

Wedale, a parish which is now called by the name of its village, "the

Stow." There is a very ancient tradition, that King Arthur brought with

him from Jerusalem an image of the Virgin, "fragments of which,"says a

writer in the eleventh century, "are still preserved at Wedale in great

veneration." About the beginning of his reign, King William issued a

precept to the ministers of the church of Wedale, and to the guardians of

its "peace," enjoining them " not to detain the men of the Abbot of Kelso

who had taken refuge there, nor their goods, inasmuch as the Abbot was

willing < to do to them, and for them, all reason and justice."

In the year 1144, David I.

granted the Church of Lesmahago as a cell to Kelso, and by the same

charter conferred upon it the secular privilege of sanctuary in these

terms "Whoso, for escaping peril of life or limb, flees to the said

cell, or comes within the four crosses that stand around it; of reverence

to God and St. Machutus, I grant him my firm peace." To incur the censure

and vengeance of the Church was sufficiently formidable; but to break "the

king's peace" brought with it something of more definite punishment. It

was not the mere mysterious divinity that doth hedge a king: "The king's

peace" was a privilege which attached to the sovereign's court and castle,

but which he could confer on other places and persons, and which at once

raised greatly the penalty of misdeeds committed in regard to them. By our

most ancient law, the penalty of raising the hand to strike within the

king's girth was four cows to the king, and one to him whom the offender

would have struck; and, as I have already mentioned, for slaying a man "in

the peace of our lord the king," the forfeit was nine score cows to the

king, besides the assythment or composition to the kin of him slain "after

the assise of the land."

In granting the same

privilege to Inverlethan, Malcolm IV. ordains, "that the said church, in

which my son's body rested the first night after his decease, shall have a

right of sanctuary in all its territory, as fully as Wedale or Tyningham;

and that none dare to violate its peace ' and mine,' on pain of forfeiture

of life and limb.'' Of the sanctuary of Tyningham, thus mentioned as of

almost equal celebrity with Wedale, we have but little further

information.

The Scotch law of sanctuary

or girth was early ascertained with much precision, and carefully guarded

from the danger of encouraging crime by affording an easy immunity to

fugitives. In later times, and during a period of intolerable misrule,

among other temporary enactments for the suppression of homicide, the

Parliament of Scotland enacted that whoever took the protection of the

Church for homicide should be required to come out and undergo an assize,

that it might be found whether it was committed of "forethought felony,"

or in "chaudemelle;" in case it should be found of chaudemelle, he was to

be restored to the sanctuary, and the sheriff was directed " to give him

security to that effect before requiring him to leave it." |