|

"I

AM a man of sentiment only," says Tommy in "Tommy and Grizel," speaking

for his creator, Sir James Barrie. He would be different if he could, we

feel, and yet, what man is more noble than the man of sentiment? This

particular "man of sentiment" came from "I

AM a man of sentiment only," says Tommy in "Tommy and Grizel," speaking

for his creator, Sir James Barrie. He would be different if he could, we

feel, and yet, what man is more noble than the man of sentiment? This

particular "man of sentiment" came from

that land of conquerors, Scotland, as long ago

as 1883, eager to subjugate literary England. As journalist, as essayist,

as novelist, as playwright, he has caught us completely in the web of his

phantasy, and made us all willing

partners in his dreams. Last of

all, he has entrapped that most concrete and matter-of-fact institution,

the cinema, and has voyaged to America, there to watch over the adventures

of Peter Pan

in film form.

Sir James Matthew Barrie was born at

Kirriemuir, in Perthshire (the

"Thrums" of so many of his books), on

the 9th May, 1860. His boyhood was passed at Kirriemuir and at Dumfries,

where his elder brother was inspector of schools. In "‘Margaret Ogilvy,’

by her son J. M. Barrie," most of the secrets of that son’s childhood are

laid bare. First and foremost Barrie was certainly not born with a silver

spoon in his mouth, for he writes: "On the day I was born we bought six

hair-bottomed chairs, and in our little house it was an event

. . .

they had been laboured for."

Barrie must have passed a joyful

childhood, since no child could have had a more delightful mother than

"Margaret Ogilvy," who brought him up. A rich imaginative atmosphere

helped to eke out their slender financial resources. By schemes and plans

and economies, all entered upon in a spirit of laughing adventure, the

means were found for Barrie to be put to school at Dumfries Academy. From

there he proceeded to Edinburgh University—a

step

which involved the most thrilling adventures of all in domestic economy.

Mother and son played a game together of pretending that "it would be

impossible to give me a college education." But, continues Barrie, "was I

so easily taken in, or did I know already what ambitions burned behind

that dear face?"

Nevertheless, her son’s true

education took place neither at Dumfries nor at Edinburgh, but by

"Margaret Ogilvy’s" own fireside. "We read many books together when I was

a boy, ‘Robinson Crusoe’ being the first (and the second)." When he was

eleven, James and his mother had fully embarked on a career of literary

phantasy together. "Margaret Ogilvy" suggested that her son should write

tales for himself. "I did write them, but they by no means helped her to

get on with her work, for when I finished a chapter I bounded downstairs

to read it to her, and so short were the chapters, so ready was the pen,

that I was back with new MS. before another clout had been added to the

rug" (which Margaret was making).

Thus mother and son shared a life in

which the imagination surpassed all else in importance. Through the attic

window of their cottage, Barrie "could see nearly all Thrums." Looking out

from this window, Barrie, imbued with that intimate blending of keen

perception and whimsical fancy which his mother and he had so much

developed in their daily life, unconsciously, and without premeditation,

wove in his mind the materials which were later to be incorporated in his

"Auld Licht Idylls," "Margaret Ogilvy," and "A Window in Thrums." His

mother shaped his mind in these happy days at Kirriemuir. All his fancy,

all his sentiment, all his whimsical charm, originated in the years he

spent with the delightful, tender-hearted "Margaret Ogilvy."

In 1882, Barrie graduated from

Edinburgh University as M.A. In his earliest days at Edinburgh Barrie had

revived his childish dreams of authorship, and had written a three-volume

novel. Mother and son packed up the MS. with the greatest care and sent it

off to a publisher. "The publisher replied that the sum for which he would

print it was a hundred and—however, that was not the important point (I

had sixpence); where he stabbed us both was in writing that he considered

me a ‘clever lady.’ I replied stiffly that I was a gentleman, and since

then I have kept that MS. concealed. I looked through it lately, and, oh!

but it is dull. I defy anyone to read it."

Determined to be an Author

About the time he left the

university, two maiden ladies asked Barrie what he was to be. "When I

replied brazenly, ‘An author,’

they flung up their hands, and one exclaimed reproachfully, ‘And you an

M.A. !‘" For in Scotland then all

M.A.’s aspired to the ministry. But Barrie’s mind was made up; an author

he would be, so he cast about for the best avenue of approach to the

literary Muse.

Owing to his sister seeing an

advertisement in a paper for a leader writer on the Nottingham Journal,

Barrie obtained his first journalistic appointment—for he had decided,

on "Margaret Ogilvy’s" advice, to approach literature through journalism.

He went to Nottingham in February, 1883, and for eighteen months and more

he wrote often as much as four columns a day of political leaders and

miscellaneous articles signed "Hippomenes," and "A Modern Peripatetic."

For those who would learn more of his Nottingham experiences, Barrie has

published a full record of them in his "When a Man’s Single."

"An Auld Licht Community"

The Journal’s leaders,

however, did not absorb all his Scottish energy, and Barrie was busy

"trying journalism of another kind and sending it to London, but nearly

eighteen months elapsed before there came to me, as unexpected as a

telegram, the thought that there was something quaint about my native

place." Acting on this thought he wrote an article entitled "An Auld Licht

Community," and sent it off to the St.

James’s Gazette.

The article was accepted. Barrie was

over-joyed with his good fortune, and also with the St. James’s

Gazette. "To this day," he wrote (before the paper was incorporated

with another), "I never pass its placards in the street without shaking it

by the hand." Moreover, the editor of the

Gazette soon

wrote asking for more; and so, early in 1885, Barrie bade farewell to

Nottingham, and moved to London, where he contributed regularly to the

St. James’s Gazette, the Anti-Jacobin, and the

Edinburgh Evening Dispatch.

Shortly after his arrival in London,

Barrie collected together his "Auld Licht" sketches and, with their

publication in the form of a book in 1888, he may be said to have

graduated formally from journalism to literature. He was lucky in being

able to leave journalism while he still enjoyed the fun of it all—before

he had grown oppressed by the dreary task of daily grinding out the

maximum number of words upon nothing in particular in the minimum number

of minutes.

A New Vein of Humour

Quick on the heels of "Auld Licht

Idylls," which is a group of sketches portraying the

adherents of a particular community in

Kirriemuir, came "A Window in Thrums" (1889),

and "The Little Minister" (1891). In these books Barrie worked a new and

rich vein of Scottish humour. He appeared as something entirely new in

English letters, a whimsical and sentimental humorist, who was yet as

racy, as full of local colour and idiomatic phrase as Dickens or Sterne.

He again, in his own inimitable way, did what Dr. Johnson claimed for

Samuel Richardson—"enlarged the knowledge of human nature and taught the

passions to move at the command of virtue."

First Successful Novel

Hitherto, he had mainly been content

to appear as a droll, but "The Little Minister," his first successful

novel, made him ambitious for a novelist’s laurels. In consequence,

"Sentimental Tommy" (1896), and "Tommy and Grizel "(1900) made their

appearance. In these two works Barrie touches the sentimental chord almost

exclusively—one might almost say he exploits his own sentiment a trifle

ruthlessly.

His genius is not entirely fitted to

analyse, to construct, to theorize over his puppets; he had not the manner

to follow up the then recent triumphs of George Meredith and Thomas Hardy.

Of course, his novels have their ardent devotees; but, without

exaggeration, one might say that their place, in comparison with his

plays, is no more important than the place George Bernard Shaw’s "Novels

of My Nonage" take in relation to his great creations for the theatre.

Before the plays, however, we must

consider Barrie’s children’s books, for in "The Little White Bird" and

"Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens" Barrie has scored a success as personal

and as positive as Lewis Carroll’s. Sentiment for its own sake was the pit

which yawned beneath Barrie’s feet in his novels, the pit into which he

sometimes vanished. In "The Little White Bird," however, he blends

delicate pathos with fairy laughter in exactly the right proportions with

an indescribable deftness of artistic touch. It is a children’s book— but

one for children of all ages, the older the better, perhaps.

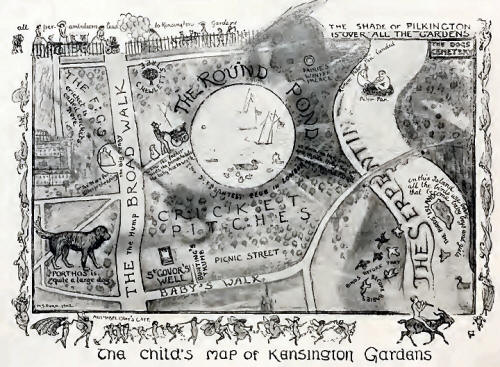

"Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens,"

of course, is one of childhood’s most supreme joys. How many thousands of

small hearts have thrilled when someone has started to read (possibly for

the fiftieth time) that entrancing narrative which begins to unfold with

the magic words: "Kensington Gardens are in London where the king lives."

It is, very possibly, the quintessence of Barrie, an idyll into which he

has managed to distil more fairy essence into anything else he has done.

Barrie first attacked the theatre

with a play called Walker, London, a play which has now been

largely and justly forgotten. It met nevertheless, with some success, and

he follow it up quickly enough with The Professor's Love Story

(1895), which Mr. Granville Barker has called "about as cynically bad a

play any man of its author’s calibre could expect to write, tried he never

so hard." So far Barrie had been trying his hand, had been experimenting

to see if his fancies and ideas were suited to the glamour of the

footlights.

Production of Quality

Street

However, these experiments bore

ample fruit in Quality Street, that charming echo of Napoleonic

Wars, which was produced with immense success during 1903. Quality

Street first showed us, on the stage, the Barrie with whom we are now

all so familiar—the dramatist, all taste and sensibility, whose dialogue

can paint a picture more surely and delicately than all the art of

scene-painters and the resources of wardrobe mistresses.

The Admirable Crichton

quickly followed Quality Street (both plays, in

fact, being produced in the same year), and Barrie took another step

forward. As daringly as ever he balanced his romance on the edge of the

impossible yet he added a spice of satire to his humorous sentiment.

The remarkable idea of the complete

Butler Crichton changing places with his master, Lord Loam, on a desert

island, and doing so naturally and quietly, is one of Barrie’s most elfin

inspirations of genius. The play scored an instant and immense success. It

has been equally successfully revived since. With The Admirable

Crichton, moreover, Barrie stepped into the foremost rank of

playwrights.

The Spell of Imagination

There is not space here to mention

all his subsequent plays. He has written a play about politics in What

Every Woman Knows. At less you think it is going to be a play about

politics; but Barrie (as usual) takes you in completely, and really the

echoes of politics only resound in the background, for Barrie could never

flatter politics with his serious attention—the things of the imagination

held him too completely in happy thraldom.

In 1904, Peter Pan was first

played in theatre. It has remained an annual fixture ever since, and is

the stage counterpart of Barrie’s children’s books, which have already

been mentioned. Completely at liberty to cast possibility to the winds, to

follow his fancies unrestrained, Barrie is here absolutely at his ease,

treating the theatre as a gigantic toy. Mr. Darling, who will not take his

medicine, the children’s Newfoundland dog nurse, John’s top-hat turned

into a chimney-pot, the pirates, the ticking crocodile, the Indians, the

great appeal, "Do you believe in fairies?" (made to the audience that the

dying fairy may be restored to life)—all these, and many more, crowd into

our memories.

Courage of Their Faith

The very unreality of the play is

its main strength, especially with children. Maeterlinck and Barrie,

almost alone among modern playwrights, have been bold enough to put

creatures quite divorced from life on to the stage, without ostentatiously

labelling their pieces "Fable," or" Allegory," or some such name. They

have been brave enough to put into practice their faith that the

imagination, beyond all else, is what counts.

The reader may complain, having read

thus far, that while something has been said of Barrie’s works, little or

no mention has been made as to what manner of man he is himself. To which

objection only one answer can be given, namely that, apart from his works

and what autobiographical details he himself has chosen to reveal, we do

not know. We do know, however, that unlike most literary men, Barrie does

not indulge in many recreations. In his younger days he could wield a good

bat at cricket, but beyond this sport, and the great solace which he

derives from his much loved pipe, he has very few hobbies indeed.

Fondness for Tobacco

The fact must not be neglected—how

evident it is—that Barrie enjoys tobacco as much as any other man might

enjoy billiards or collecting rare pieces of china. He is a devoted

servant to the "fragrant weed." He has even gone to the extent of proving

his devotion in a little book which he called "My Lady Nicotine."

There is a story told which, if it

be true, well illustrates the author’s intense dislike for all unnecessary

conversation. One day a lady visitor made an unexpected call on Barrie and

found him smoking in a room, in company with one of his male cousins.

For a long time she tried her utmost

to engage the author in conversation, choosing her subject with a tact

which would have done considerable credit to a diplomat. The attempt was a

miserable failure. Apart from giving monosyllabic answers to her

questions, Barrie remained silent, puffing away at his briar.

At last, in desperation, the visitor

left the room, chagrined that success had not rewarded her efforts. About

an hour later she returned. The two men were still in their same

positions, clouds of smoke were still ascending from the two pipes, and

the same silence enshrouded them.

"Well, you

are having a

lively time!" she exclaimed sarcastically.

"Fine," drawled Barrie. "We haven’t

spoken a word since you went away."

Rector of St. Andrews

University

Sir James Barrie is a member of the

Athentaeum Club. He was created a baronet in 1913, and has been Rector of

St. Andrews University in his native country. But all these external

details, and the many more that could be added of a like nature, do not,

in his case, give us much information. The details of the lives of many

men, of many great men, disclose the secrets of their character and

ambitions, but such a method is useless in dealing with Barrie.

The only ways in which we can learn

anything about such as he, is by reading his books, by going to see his

plays, and by listening to his rare speeches—which are surely delightful

methods. On the rare occasions when Barrie can be persuaded to adopt the

role of public speaker, he sometimes gives interesting revelations of

incidents that happened in his boyhood days, the days that are

ever-present in his memory.

Of his schooldays he has a fund of

whimsical anecdotes. He has told the public how he suffered from the

terrible habit of reading "penny dreadfuls," and the way in which he was

cured. The following is the actual account he gave of his terrifying

experience:—

In those tender days, I used, when

in funds, to devour secretly penny dreadfuls, containing exclusively

sanguinary matter. They were largely tales about heroic highwaymen and

piracy on the high seas; but what most enamoured me were the stories of

goings-on at English boarding-schools. Those were the schools for me.

The masters were sneaks, and the

boys blew them up with gunpowder. My mind became so set on explosions that

when a Sassenach sent me a box containing mysterious red and blue tubes I

placed them one by one near the fire, and darted back in confidence that

they would go off. I dare say I wept when I discovered that they were only

coloured chalks.

In "Chatterbox" I read an article on

the dire future in store for those that read. penny dreadfuls. I tried to

stand up to it, but when black night fell I stole off to a distant field,

my pockets stuffed with back numbers, a shovel concealed up my little

waistcoat, and deep in the bowels of the earth I buried the evidence of my

guilt.

Some Characteristics

Barrie is the sort of man who makes

his elfin Peter Pan remark "To die would be an awfully big adventure." He

is the sort of man who conceives of a London police constable as the hero

of a play, and then makes him as whimsical, as poetic, and as fanciful as

he is himself. The sort of man who, though he knows literature from the L

to the last E, yet writes always so simply and unpretentiously that

everyone can understand him, even what someone has called "those small

aborigines, whose cave-dwellings and rock-shelters are under piano and

table." In short, Barrie, like Peter Pan, is the sort of boy who never

grows up.

Tremendously shy, or else we should

know much more about him than we do, Barrie has become a great force in

our English theatre. He has founded no school, because his genius is far

too intensely individual to afford much food for professional disciples.

But, desperately laying his shyness aside, he slips into the theatre

whenever his plays are being produced, and in the most tentative and

hesitating way he makes suggestions. Suggestions, moreover, on which the

most gifted and experienced of actors are only too delighted to seize. In

a word, he has transformed the acting in London.

You can read an

e-taxt of Peter Pan here

See an

account of James Barrie with genealogy from John Henderson

An

Edinburgh Eleven

Pen Portraits from College Life

By James Barrie

The Little White Bird

In 1902 J.M. Barrie published 'The Little White Bird', a pretty

fantasy, wherein he gave full play to his whimsical invention, and his

tenderness for child life, which is relieved by the genius of sincerity

from a suspicion of mawkishness. This book contained the episode of

"Peter Pan," which afterwards suggested the play of that name.

We are now in the process of serializing this book with

a chapter per week intil complete.

CONTENTS

Chapter I - David

and I set forth upon a Journey

Chapter II - The Little Nursery Governess

Chapter III - Her Marriage, her Clothes, her Appetite and an Inventory

of her Furniture

Chapter IV - A Night-Piece

Chapter V - The Fight for Timothy

Chapter VI - A Shock

Chapter VII - The Last of Timothy

Chapter VIII - The Inconsiderate Waiter

Chapter IX - A Confirmed Spinster

Chapter X - Sporting Reflections

Chapter XI - The Runaway Perambulator

Chapter XII - The Pleasantest Club in London

Chapter XIII - The Grand Tour of the Gardens

Chapter XIV - Peter Pan

Chapter XV - The Thrush's Nest

Chapter XVI - Lock-Out Time

Chapter XVII - The Little House

Chapter XVIII - Peter's Goat

Chapter XIX - An Interloper

Chapter XX - David and Porthos Compared

Chapter XXI - William Paterson

Chapter XXII - Joey

Chapter XXIII - Pilkington's

Chapter XXIV - Barbara

Chapter XXV - The Cricket Match

Chapter XXVI - The Dedication

Margaret Ogilvy

By her son J. M. Barrie, Second Edition (1897) (pdf)

A Window in Thrums & Auld Light

Idylls

By J. M. Barrie (1913) (pdf) |