|

PANAROCKEN

We left Soerabaya early

in the morning on the railway for Baraboedoer. The first ninety miles

were through a level country, the richest I had ever seen. The soil is

mostly of decomposed volcanic ash, deep and black, with a clay subsoil.

The principal crop is sugar ; then tobacco, rice, and tapioca, for

export, and fruits of all kinds for local use. There are great sugar

mills all over the country with tall, brick smoke stacks that look like

lighthouses, all whitewashed. In fact, every building in this country is

white. A law compels the natives to whitewash their dwellings, inside

and outside, twice a year for sanitary precautions, which is said to

make them immune from cholera and the plague. At the time of our visit

the place was very healthy, although we were there in the middle of

summer when it was very hot.

To come back to sugar. A

great many men are employed in this industry. We saw them in the fields

everywhere. cutting the cane, transporting it by small railroads to the

mills, and in many places it was hauled in great, heavy, two-wheeled

carts drawn by two small oxen. The roads are perfectly level and very

good. On all the principal roads there is an avenue of trees on each

side, the branches of the trees touching on top, so that the sun does

not reach the road at all. As a rule, there are irrigation ditches on

one side of the road,

A man has charge of a

short piece of road which he has to sweep clean every day, burn all dead

leaves and refuse, and also sprinkle his division with water which he

dips with a pail out of the running stream by the roadside.

Rest houses, built by the

Government, are located every five miles. The houses are built across

the road and are open on all sides. During rain storms teams can drive

under the roof, and travelers can be down on the bamboo beds and rest

themselves. These buildings are kept nicely whitewashed and clean. There

are also small rest houses about one and a half miles apart, between the

larger ones, wherever there are roads. These roads are generally about

forty feet wide.

Sugar cane is hauled to

the mills, and an elevator, like a slab elevator in a sawmill, carries

it to the rollers where it is crushed. The first rollers are not very

close together, the second are closer, and the third squeeze everything

out of the stalk with the assistance of hot water that is sprinkled on

the cane before it goes through these last rollers. The refuse cane is

then carried to the grates to make steam They use extension fronts, the

same as we use in some sawmills. That is an oven in front of the boilers

where the cold cane goes in and nothing but hot flame goes under the

boiler. I do not understand the process of sugar making sufficiently to

explain it, but the juice is carried in troughs, whence it is pumped

into great boilers, and there belied with the exhaust steam from the

engines under a vacuum. After going through several of these, it becomes

thick and is then put into cylinders that revolve very fast. The

centrifugal motion takes the syrup and impurities out of it and the pure

sugar is then delivered into a bin, later being put into sacks, baskets

or mats.

The sacks are just

ordinary strong gunny sacks, well sewed up at the end. The baskets, with

which our steamer was loaded, were something new to us. They are about

four feet long, tapering from two feet at one end to about two and a

quarter at the other. They are strongly made of split bamboo, and are

placed small end down and carefully lined inside with large banana

leaves. The sugar is shoveled in until the mat is full and its top is

securely covered with leaves, then a cover of bamboo is put on and

securely sewed down with bamboo thongs, making a very strong and very

heavy package. They run from five hundred and fifty to seven hundred

pounds when packed with sugar.

In our cargo they

averaged three and one-half baskets to a ton of 2240 pounds, or six

hundred and forty pounds each; but different fare is allowed in

different places. The picul here is one hundred and thirty-six English

pounds, and in China it is only one hundred and thirty-three and

one-third pounds. This sugar was sold on a Java picul basis, and we got

freight on the basis of a Chinese picul, so that on account of the

different customs it is difficult to know and understand exactly what is

meant by a basket of sugar or a picul.

We found the baskets much

larger at Panarocken than at Soerabaya. They are difficult to stow

tight, and it is slow-work finishing up a ship when they get close up

under the beams. The steamer was not quite full, and, even if she had

been, she would have been to her loadline by two hundred and fifty to

three hundred tons. But with bags or mats she would have been down to

her loadline and still have room left. The mats are about two and a half

feet square, made of matting and holding from seventy-five to a hundred

pounds of sugar. They are not very strong, and while they stow well,

there is danger of their breaking.

Most of the mills ship

their sugar by rail to the seaboard. but many of them haul it with ox

carts. There are very large warehouses at all the shipping ports and

very good facilities for handling it. The sugar ports are. beginning

with Soerabaya (which is the principal one), going east—Pasuruan.

Probolingo, Bezukie, Panarukan and Ban-luwangi, which is on the east end

of the island. Then going west from Soerabaya, are, Samarang, Cheribon

and Batavia, which is the capital and important as such but has little

importance from a commercial standpoint. On the south side of the

island, about the center from east to west, is Tjilatjap. the only good

port and the only one of any importance on that side.

Continuing our journey

across the island, after the first ninety miles through a rich country,

there were twenty-miles over foothills, planted out in trees of no great

value.

After crossing- the

foothills we got into another stretch of rich, level ground.

At Solo we changed cars

from narrow to broad gauge. Two hours time brought us to Jokjokarta, for

short called Jokja. This is where the headquarters of the native princes

are situated. They are paid by the Dutch Government, and their palaces

and grounds occupy six hundred and forty acres in the center of the

city. They have from ten to twelve thousand attendants, all living

within the walls of this enclosure. We did not have time to visit the

palaces as it takes time to get a permit, but we visited the water

castle built in 1750 for native princes.

This castle has been

abandoned since it was wrecked by an earthquake and is fast going to

rack and ruin It was surrounded by water and there are many underground

chambers where they would retire during the hot weather. The walls are

thick, and, before modern artillery came into use, it was a very strong

place. The shady avenues around this city are very fine and give one the

impression he is driving through some gentleman's estate in England.

In going along we noticed

that there were no scattered farmers' or peasants' houses to be seen, as

they live in villages fenced or walled in and completely shaded with

trees, so that you cannot see the houses until you are quite near them.

Whenever you see a banana and cocoanut grove you may be sure a village

is there. Every house has a small piece of ground in which are banana

and cocoanut trees, which, together with rice, are used for food.

As this island is about

the most thickly populated part of the world you can imagine the number

of villages there are. On the roads wherever we went there was a

constant stream of people going and coming and generally carrying

burdens; the women carry their burdens on their heads, which gives them

an erect and stately appearance. The people seem to be industrious and

are always working at something. Most of the tilling of the soil is done

by hand.

Considerable rice is

grown here. We saw it in every stage from the sowing of the seed in beds

before it was transplanted, until it was being threshed by being pounded

in a wooden trough. It was then pounded, to get the hull off, in a

three-inch auger hole in the end of a log—a piece of wood like a capstan

bar being used. Some of the people are engaged in cultivating tobacco,

which we also saw in its various stages. There are some very large

factories for the preparation of the leaf before it is shipped to

Amsterdam. It is packed into good solid bales, four feet square, which

are covered with good burlap.

In connection with labor,

it is a remarkable thing that, although there are a quarter of a million

Chinese in Java, I never saw one of them doing manual labor—the natives

do all the hard work. For instance in the sugar mills, after the cane

goes through the mill and they commence to boil the syrup, the Chinese

take charge of it, under the Dutch chemist. The retail business of Java

is done by Chinese, and many of the merchants are very wealthy The

authorities compel them to wear their queues so they will always know

them, but as a great many of them are half caste their pig tails have

dwindled down to the merest string.

BARABOEDOER

From Jokia we left for

Baraboedoer. We took the steam train to a place called Montelan,

twenty-two miles distant. There are no Europeans here, except a few

Government officials. From there we took a four-horse wagonette. The

horses are about the size of a large Shetland pony, and are very hard to

drive. It takes two men to drive them, one sitting in front lashing them

with his whip, while the other runs alongside to lash them. The roads

were level and in excellent condition, with the usual avenue of shade

trees to keep the sun off. The distance from Montelan to Barabjoedoer is

about eight miles, and there are three prosperous villages between the

towns. We met a constant stream of people going and coming all the time,

but could not find a single person who could speak English, so we had to

depend on what we saw for any information we got. There s only a ruin at

Baraboedoer and the Government hotel, called a ''passagrahin," which is

only used for visitors to the ruins, and from a glance at the register,

there are not many, and most of those who do go are from the island. The

American visitors are few and far between.

When we arrived I tried

to pay the driver, but the hotel keeper did not want me to. He kept

saying "Morgen," but as I was not acquainted with the word we could come

to no understanding. He was quite disgusted, but we finally found a book

giving English words with their Dutch meanings, and I found "Morgen" to

mean "tomorrow." So by finding words and using signs we managed to get

along. Darkness comes on very suddenly in the tropics so we had no time

to see anything that night, but the next morning at daylight we started

out.

I must tell about a Java

bed. It is usually seven feet long by eight feet wide, with lots of

pillows and bolsters, the whole covered with mosquito netting stretched

on four poles. There is a sheet over the mattress, but that is all—no

bedding. The netting is supposed to keep you warm enough. All the floors

are cement and some of them are just the bare cement without any mats or

rugs on the floor. All the houses are of one story.

The Temple of Baraboedoer

is a wonderful building. It would be impossible for me to give even a

faint idea of the immensity of the building or of its sculpture. It is

over thirteen hundred years old, and I think it outrivals anything in

the world of its age. It is built on a hill, say three hundred feet

high, the building being one hundred and three feet in height to the

top. The first base is two thousand and thirteen feet in circumference,

then each story recedes about forty feet in diameter and there is a walk

around each story of twenty feet in width. It is seven stories high and

is completely covered with statues and bas-reliefs, except the lower

story, which had not been finished. It is thought that it took many

years to build and carve, and troubles arising between the native

tribes, it was never completed. Fortunately, before leaving, they

covered it with earth, which accounts for its fine state of

preservation. In addition, there was a heavy coating of volcanic ash (it

is in sight of a smoking volcano at the present day), then trees and

shrubs completed the covering. The bas-reliefs are supposed to show all

the events of Buddha's life, from before the time of his birth until

after his death.

I noticed several models

of ships which looked much like the ships used by Columbus. The whole is

built of a very dark colored stone and is surmounted by a dome on which

was a spire, long since demolished by earthquakes The dome was built up

but the Dutch opened it and found within a very large carved image of

Buddha, not completed. This is still open to visitors. The credit of

bringing this great work to light is due to the English. When they got

possession of the island in 1812, the governor had part of it unearthed.

It was a great work, and two hundred men were employed for a long time.

Afterwards the Dutch completed the uncovering of it. At one time they

had a number of soldiers in the vicinity who -wantonly destroyed many of

the figures by shooting at them, and deliberately smashed many. But now

the Government is taking care of it. Every one used to go there and help

himself to whatever he wanted. At that time, many persons and museums

obtained a fine lot of relics from the rums. Several days would be

required to comprehend the extent and magnitude of the structure.

Two miles from here is

Mendoet, another ruin that the Government is restoring. It occupies a

piece of land about two hundred by four hundred feet, and is surrounded

by a paved court and a mound of earth. Likely, it was walled in at one

time. The building is about forty-five feet square and probably

seventy-five high. Inside the building there are three mages of Buddha,

all in a fine state of preservation. The bas-reliefs, and the outside

generally, resemble Baraboedoer, which apparently goes to show that it

was built about the same time and by the same people. There is a large

village surrounding the ruins, but they had no idea of its existence

until a Dutch engineer discovered it in 1835. It will be a fine monument

when the work of restoration is completed.

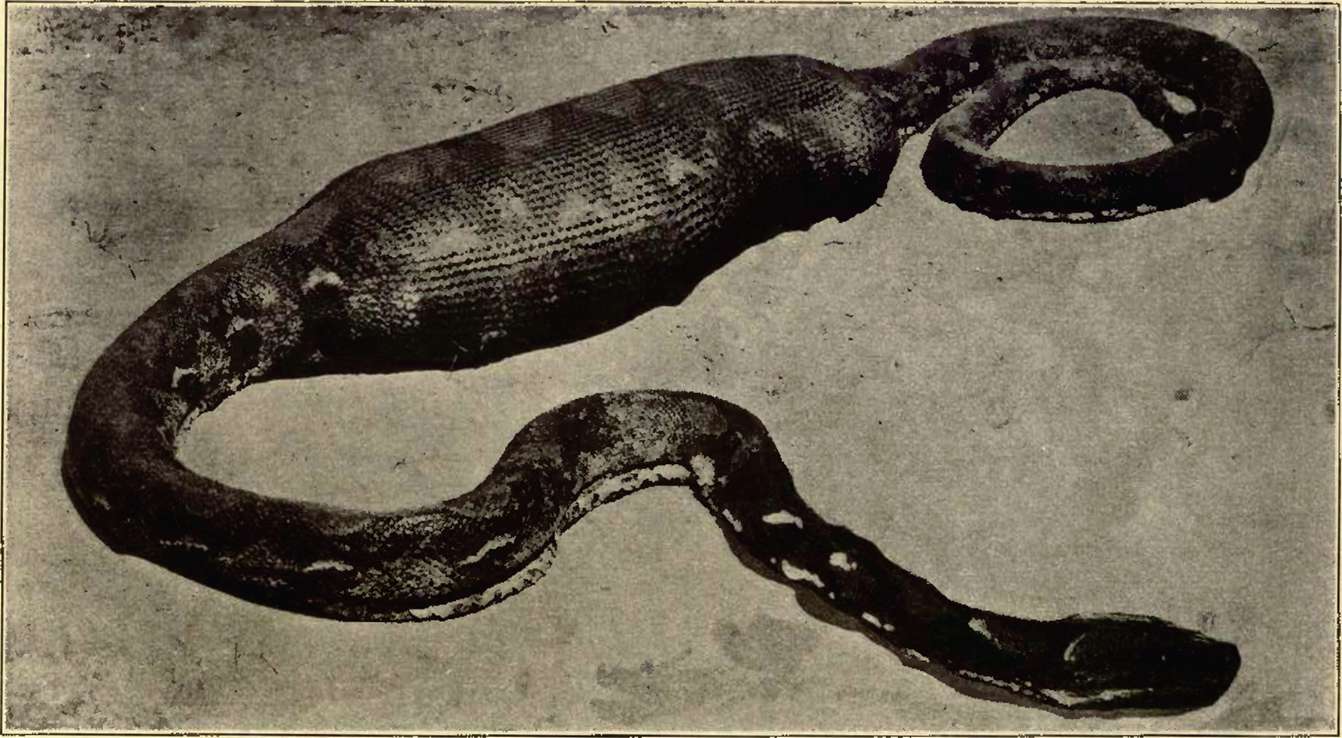

A SNAKE AFTER HAVING DINED ON A SMALL FIG—FASURUAN, JAVA

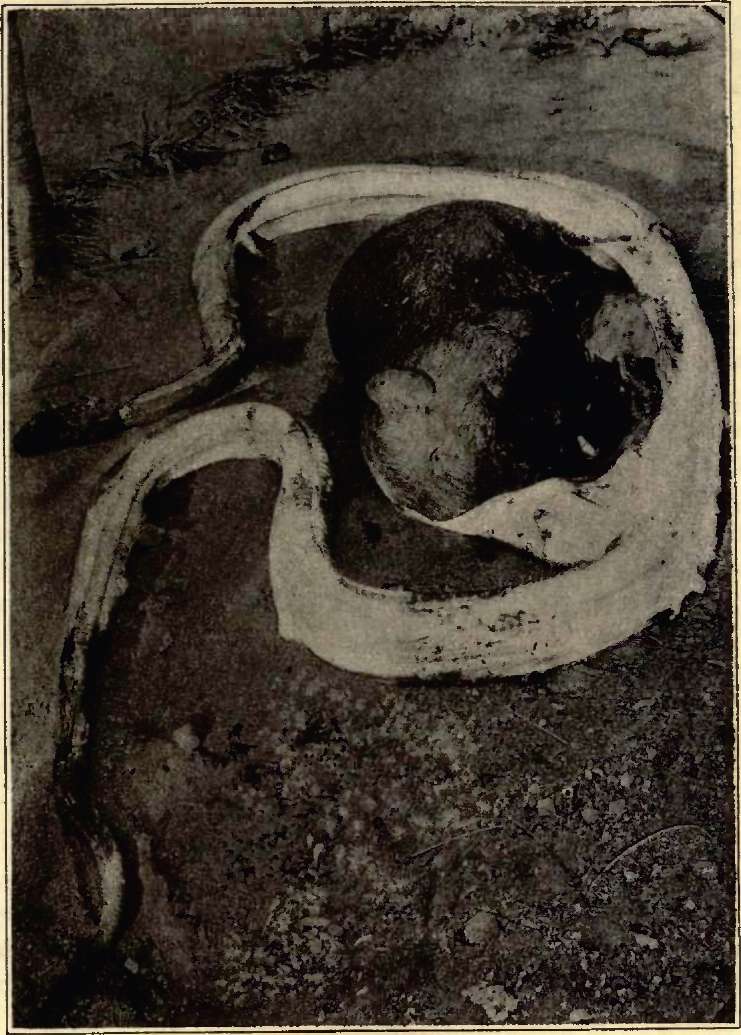

THE SAME SNAKE- EXPOSING TO VIEW THE BOOT OF THE PIG

SOLO

At Solo we saw the

resident Prince's palace. He had a menagerie of wild beasts, and three

elephants kept for state purposes. The royalties keep up a lot of empty

style, and the Government uses them for its own purposes and to keep the

natives quiet, but I noticed a battery of large cannon in a square that

covers the palace, so that at short notice a volley could send all the

grandeur skyward!

We had to retrace our

steps to Soerabaya as we wanted to see a real, live volcano. We left the

cars at Pasu-ruan, a seaport, which formerly was of great importance,

but since the railways have been built trade has gone to Soerabaya There

are a number of good buildings and warehouses situated, as at Soerabaya,

on the sides of the creek or river, where the large lighters load and

discharge their freight. Steamers lay to an anchor a half mile from the

mouth of the river, the navigable part of the river up to the heart of

the town being two miles.

One day while here we

heard a great deal of commotion and on coming near the scene found a

large snake had swallowed a small pig and had been killed by some of the

natives.

The country is very

level. We found it difficult all through the island to talk to the

people, but managed to find some one in most places who could speak a

little French so managed to get on.

At Pasuruan we had quite

a wait but finally got started for the Hotel Tossaira. We went in carts

and the hotel man at the station told us when we came to Passeuan to pay

the men off and two others would be waiting for us. The first went about

ten miles and stopped and wanted us to pay and get out, but as we could

not understand them we came to a deadlock. We would not get out, and

they would not go on. One of them went off and brought a Dutchman, but

we could not understand him any more than the natives. After a great

deal of talk that neither party understood a bright thought struck the

Dutchman. He beckoned me to follow him to where there was a telephone.

He called up a town and got a party on the line and then gave me the

receiver; to my astonishment this party could speak good English. He

explained to me that we were at the end of our first stage, to pay off

our teamsters and take other carts as the horses we had could not climb

the hills. So all the trouble was over and the mob dispersed, as the

whole village had turned out to see the circus with the foreigners.

From here we had two

horses to each cart, one in the shafts and one alongside, but the grade

was very- steep and hard climbing. At first the grade was rocky,

evidently lava from some eruption, but the land was cultivated between

the boulders. We now commenced to see lots of Indian corn, no rice but

plenty of bananas. While the road was steep, it was wide and well made,

and kept in excellent condition. We arrived at Posepo at noon and had

lunch at the Government hotel. After lunch we got saddle horses and two

men to carry our bags, as the grade was steeper from here on, but the

road was just as good and as well kept, and the avenues of trees

continued. A rain storm came on us suddenly and we were drenched. We

came to a native house and took shelter until the storm passed over. We

were now five thousand feet high and the weather was decidedly cooler

than at the seaboard. The house was bamboo throughout, even the roof was

bamboo split in two. One row with the mouth up and then another row with

the hacks up, which made a perfectly tight roof. The smoke found its way

out through the cracks, and consequently into our eyes. The floor was

dirty and the cooking stove was made of stones and clay. Altogether it

was very primitive. The building was about thirty by twenty feet, and

there were evidently two or more families living in the house, for

twenty people who had never seen Americans before, came to take a good

look at us.

It cleared up and we

armed at the Government hotel at Tossaira before dark. The next morning

we were off again on horseback to see the volcanoes. It took us four

hours' riding to get to Bromo, which is the active one. Great quantities

of black smoke were rising from it occasionally, and from a considerable

distance we could hear the most unearthly noise coining out of it. There

are two extinct volcanoes close to this one; in fact, they are all

within three miles of each other. Widoudaren, the first we came to,

looks as though it had cooled down lately as there is no vegetation on

it yet. The same can be said of Batck. This one looks like a perfect

cone flattened on top, the sides all corrugated into deep ravines as the

lava had run down into what is called the sand sea. Looking down on this

sea it looks just like a lake. Some of the natives had come to worship

the fire god and had built wooden steps of teak and bamboo to the top of

Bromo. As it is very steep we left our horses at the foot and walked up

the stairs. The top of the rim is very thin, not more than ten feet, and

the crater is so steep no one could walk down. When the smoke would blow

away from the bottom it looked like great holes, with boiling liquid

inside--the whole yellow with sulphur.

The nearest comparison I

can make to the noise would be standing in a boiler room where there

were several batteries of boilers and all blowing off at the same time.

The ascent from the sand sea to the top of the crater Bromo is about one

hundred and fifty feet and the bottom of the crater looked to be about

the same distance down. All around were great masses of rock and stones

that had been recently ejected. Other places were stretches of molten

lava where it had cooled off into fantastic shapes, generally cutting

deep corrugations into the hillside and all accumulating in a great bank

or ridge similar to the result of a landslide.

This is a very wild

country and from the Bromo we could see three other smoking volcanoes,

the whole making a scene of wild grandeur and desolation. One can have

no idea of the force exerted by a volcano unless he has seen one in

eruption, or has looked at one like this, just recently cooled off.

On the way to the

volcanoes we were surprised to see the hills right up to the top,

terraced and under a high state of cultivation, although some of them

were so steep that it is hard to believe they could be cultivated.

Vegetables and Indian corn are the principal products, but there is also

considerable quinine grown here.

We were on our way before

daylight the next morning to get the train at Pasuruan for Panartfeken

where the steamer "M. S. Dollar" was loading. The country the whole

distance from Pasuruan to Panarocken is level and just as rich as any we

had seen, thereby convincing us that Java is the richest agricultural

island of the world.

The principal productions

on this eastern end of the island are sugar, tobacco, coffee and some

indigo, then fruits of all kinds and rice for the native food. They seem

to have a good telephone system over the island. Foreigners were closely

watched, and we learned that notice of our arrival at the various places

on the island had always been telephoned ahead of us, and we had to have

closely vised passports. But I understand this regulation has been

modified.

VIEW OF A SECTION OF WALL, TEMPLE OF BARABOEDOER |