ON 10th October 1814, as stated above, the Society

issued its first policy of assurance on the life of David Wardlaw for the

sum of £1000, and its second on the life of Patrick Cockburn for £500—the

two men who shared between them responsibility for its foundation.

The

infant Society was now fairly under way for better or worse; but it

cannot be denied that, for some years after this, its prospects were the

reverse of encouraging. On 6th February 1815 the Manager reported that

the number of persons insured was thirty, their annual premiums amounting

to £738 : 9 4, besides entry money [Every person

effecting insurance became a member of the Society, and paid 10s. for

every £100 assured as entry money. This rule continued in force till 1847,

when entry money was commuted for a trifling addition to the annual

premiums.]; that £500 had been lodged with the

British Linen Company, and £281 in the Bank of Scotland. The solvency of

the concern depended upon what claims might arise upon this slender

capital. Happily, no considerable claims fell due at this critical stage;

the first arising through the death of Mr. Brodie on 21st January 1816 for

£oo. The minute directing payment of the claim illustrates alike the

cautious procedure of the directorate and the tardiness of communication

with the Highlands.

6th May 1816.—Upon the subject of the demand by Mr.

M'MilIan for the £500 insured upon Mr. Brodie's life, the meeting desire

the Manager to intimate to Mr. M'Millan that, altho' they are not bound by

the terms of the certificate to pay this loss sooner than three months

after proof of Mr. Brodie's decease shall have been made to the

satisfaction of a Court of Directors, which, admitting Mr. M'Millan's

letter of 8th April last (but only received at the office of the Society

on the 4th instant) to be such a proof; could only be understood to be

payable as three months from this day, yet they are willing to wave [sic]

any objection arising from this omission to the term of payment and to

consider it payable as on the 21 of July next, 6 months from the period of

Mr. Brodie's death. And they further direct it to be intimated to Mr.

Brodie's representatives that they are willing to pay the money

immediately—discounting the interest till the 21 of July upon a proper

discharge of the certificate by the persons entitled to receive the money.

Besides the good fortune attending the Society in the absence of heavy

claims during its initial stage, Mr. Cockburn's vigilance in resisting

inroads upon the Expense Fund must be accounted as having contributed in

no slight measure to its stability. Thus in July 1815, when a proposal was

considered for leaving the premises in "Society," Brown Square, [It

was by chance, not by design, that the first office of the Scottish

Widows' Fund Society was situated in a detached portion of Brown Square

named "Society." Readers of Redgauntlet may remember that Alan Fair-

ford's father moved from "his old apartments in the Luckenbooths" to Brown

Square, which is thus described by Scott in Note E to that romance "The

diminutive and obscure place called Brown's Square was hailed about the

time of its erection as an extremely elegant improvement upon the style of

designing and erecting Edinburgh residences. Each house was, in the phrase

used by appraisers, 'finished within itself,' or, in the still newer

phraseology, 'self-contained.' It was built about the year 1763-4 and the

old part of the city being near and accessible, this square soon received

many inhabitants, who ventured to remove so moderate a distance from the

High Street." Howbeit, before 1815 well-to-do families had deserted Brown

Square and migrated into the new town which had arisen on the north side.]

where business had hitherto been transacted, and renting an office "in a

more centrical situation," the directors inclined to accept the offer of a

house at the south-east corner of North Bridge Street, at a rent of £28 a

year; but when their recommendation came before the Extraordinary Court on

7th August, Mr. Cockburn vigorously and successfully opposed incurring

this additional expense. He said that, while "he certainly did conceive

that the Society having a place of business in a conspicuous part of the

town would tend very much to make the Society better known to the public,

and might be the means of acquiring a more extended accession of members,

the only objection he had to the measure was the additional expence that

must be incurred, which the present state of the Expence Fund was totally

unable to bear. He begged leave to press upon the meeting that one great

means, and in his opinion the principal and most effectual means of

encouraging an extension of the scheme, was a strict adherence to

economy." He then proposed that the directors and other friends of the

Society should undertake to guarantee "the risk of the rents and taxes."

The suggestion was adopted, and the six ordinary directors present each

gave a several guarantee of £5 making £30 in all.

However, the house in

North Bridge Street was not taken, and the office of the Society was

continued in the house of the Manager in Society, Brown Square, until

Whitsunday 1817, when it was transferred to his office at 71 Princes

Street.

It has been shown how closely the model of the Equitable Society

had been followed in forming the Constitution of the Scottish Widows'

Fund; but it soon became clear to the directors that the circumstances of

an office doing business in London were very different from those of one

in Edinburgh. The Equitable had made no effort to establish a provincial

connection, obtaining as much business as its directors cared to undertake

from members resident in London for the whole or part of the year;

wherefore they never appointed any agents. [A letter

from Mr. Morgan is engrossed on the minutes of 15th December 1817, denying

a report, circulated, no doubt, from interested motives, "that the

Equitable had ceased to take fresh business owing to the magnitude of its

engagements." New regulations, he said, had been adopted, which would

enable the Society to carry on business "to any extent without the least

danger of rendering it unmanageable from the magnitude of its concerns or

of becoming a sacrifice to the cupidity of too numerous a class of

proprietors."] Matters were different in the smaller and poorer

capital of Scotland ; unless external sources could be tapped, the

operations of the young Society were destined to continue on a somewhat

insignificant scale. Moreover, it had been set forth in the prospectus

that the purpose of the promoters was to extend the benefits of insurance

"to all parts of the United Kingdom," a design which could not be

accomplished without agents. Accordingly, by a resolution of the

Extraordinary Court on 7th August 1815, Mr Lewis Grant, bookseller,

Inverness, was appointed the first agent of the Society, to receive as

commission half the entry money and 1/4 per cent on the premiums of

members introduced by him. Before the end of the year, agents had been

appointed in Glasgow, Aberdeen, and Annan. [The

commission to agents was increased on and November 1818 to one-half entry

money and 2 1/2 per cent on renewals.] Thus the foundation was laid

of that widespread system which is now carried on through agents. Had

relations with the Equitable been less cordial and more competitive, the

managers of the English Society might surely have taunted their Scottish

foster-child with the sobriquet of the Importunate Widows, seeing that the

directors had set about obtaining business through the energy of agents.

Still the business hung fire. The gentlemen connected with the promotion

had by this time exhausted their powers of persuasion upon their personal

friends, and there was little or no response to the advertisements which

had been inserted in the press. And so it came to pass that on 20th

November 1815 the directors determined that "from the state of the funds

and business of the Society it was impossible, and in the present

circumstances seemed to be quite unnecessary," to employ both a manager

and secretary. They therefore desired Mr. Wotherspoon to take over the

whole management unaided; but whereas the removal of the secretary Mr.

Alexander Stewart's name from the list of officials "might possibly have

some effect with the public injurious to the Society or to Mr. Stewart

himself," they requested Mr. Stewart to allow his name to be retained as

secretary, although his active duties would be discontinued. The services

of Mr. Wotherspoon and Mr. Stewart having been unremunerated up to this

stage in the existence of the Society, it was decided to allot one-half of

the entry money received and two-thirds of the additions to premiums, and

to divide the amount in the proportion of two-thirds to Mr. Wotherspoon

and one-third to Mr. Stewart. Further, in consideration of Mr. Stewart's

"trouble in preparing materials for setting the establishment on foot and

in conducting the business prior to 1st January 1815," a grant of £150 was

allotted to him out of the preliminary Expense Fund. These details,

trivial as they may appear, are not without interest when read in

connection with the present dimensions of the plant reared from the seed

sown one hundred years ago by Mr. Wardlaw and his colleagues, and nursed

into growth by Messrs. Cockburn and Wotherspoon.

Some features in the transactions during 18 16 may be noted as follows.

Agents continued to he appointed in various places, a necessary condition

being that each should have an interest in the Society by insurance to the

amount of £500. So when Mr. Dugald Bannatyne, postmaster, Glasgow, while

willing to accept appointment as agent, demurred on account of advanced

age to the stipulation that he should insure his life, it was explained to

him that the necessary insurance might be effected upon the life of any

third party in which he had an interest.

It was agreed to defray the

charges for postage incurred by agents, "but with regard to stationery the

directors consider this article is too trivial to be admitted as an

article of charge."

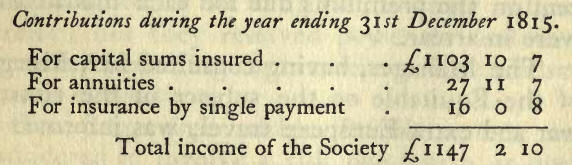

When the first balance sheet was submitted for

consideration of the directors on 5th February 1816, it showed what a

trifling amount had been received in respect of annuity insurance

(originally intended as the principal, or even the sole, business of the

Society) compared with the premiums on capital sums assured.

There was at the credit of the

Society's bank accounts a sum of £1037 : 0 : 11, which the Manager was

directed to invest in three per cent Consols at a price of £61 "or

anything under it." As this was the first investment by the Society, which

now possesses funds invested to the amount of £21,500,000, it may be noted

that £499: 6 : 6 was applied to the purchase of five per cent Consols, [The

average price of five per cent Navy Stock during March 1816 was £89.

Before the end of the year it rose to £95 :3 : 4. The three per cents

bought at £61 were sold in May 1917 at £72.] and £499 : 6 : 6 to

that of three per cents.

No claim against the Society had emerged during

the year ; and the directors considered that, even if Mr. Brodie's death

had occurred in 1815, instead of on 21st January 1816, and his claim of

£500 had become chargeable against the funds of 1815, the Society's

affairs were in a better state "than they would have been, had they

corresponded with the calculated expectation."

The first instance of

declining a proposal (for £ boo payable at death) is minuted on 18th March

1816, no reasons being given.

The first forfeitures of policies by two

members were reported on 29th July, but it was afterwards agreed to repone

them upon a payment of 2 1/2 per cent on the premiums due for each month

they were in arrear.

The Manager, having consulted Mr. Morgan of the

Equitable on the subject of the risks in war and extra-European travel,

was informed by him that his Society charged one-fifth extra premium to

cover the risk of the military profession, adding that, "in the whole

course of the recent war from 1794 to 1815, I do not believe we lost more

than five or six lives by the fire or sword of the enemy." This is less

instructive than most of Mr. Morgan's statements, for it does not present

any estimate of the number of those who, holding policies in the

Equitable, went on active service during the period mentioned, nor does

it, apparently, take account of those who died of disease. Naval officers,

and army officers serving on board ships, were called on to pay, in

addition to one-fifth extra on the premiums, 3 per cent on the sum

assured. "I do not say," continued Mr. Morgan, "that ours is a right

charge. On the contrary, it appears to me to be rather higher than it

ought to be, especially in time of peace."

So also thought the directors

of the Scottish Widows' Fund, who, "taking into view the present pacific

state of Europe," fixed i per cent in time of peace on sums assured, and 2

per cent in time of war as the extra rate to cover military service; but

they reserved power to deal with every case according to its merits and

the circumstances of the time.

Yachting, even within British waters, was

considered to involve a risk one-fourth as great as that incurred by a

soldier in time of war. The question arose in connection with an insurance

for £1000 on the life of Sir William Maxwell of Monreith, [The

present writer's grandfather. It so happens that some years later his

yacht, the Dirk Hallerick, went down at her moorings in a gale, and was

lost.] and was settled by the addition of 1/2 per cent or £5 a

year.

It may be noted that the island of St. Vincent, in the British

West Indies, bore at that time a very insanitary reputation. A proposal

for insurance having been received from a resident there, the Manager

consulted several London offices in order to ascertain the additional

rates in force for that island. He found that every office declined to

assure lives there, except the Pelican, which charged an extra rate of £8

:8s. per cent on the sum assured. Wherefore the Scottish directors decided

that "in the present state of the Society it would not be prudent to enter

into insurances of this extraordinary kind."

Mr. Wotherspoon having been

in failing health for some time, his partner in the firm of writers, Mr.

John M'Kean, W.S. and Accountant, was appointed Joint-Manager in March

1817, and, on Mr. Wotherspoon's death on 16th November 1818, Mr. M'Kean

was appointed sole Manager. Mr. Wotherspoon's case was a somewhat pathetic

one; he had laboured four or five years in the formation of the Society,

yet was debarred by the state of his health from making any provision by

insurance. Accordingly, two years after his death, the directors awarded

his representatives £100 (in addition to £150 already paid to them) and

£50 in consideration of the Society's office having been housed for two

years in Mr. Wotherspoon's residence. Mr. Patrick Cockburn, also, received

£400, "which," reported the committee appointed to deal with these

matters, "we submit to be a very moderate allowance" for the valuable

services rendered.

It was natural that the committee should desire to

recognise in a substantial manner the time and trouble which Mr. David

Wardlaw had given from the beginning; but he anticipated any action of

that nature on their part by a letter from which the following is an

extract.

EDINBURGH, 2nd Nov. 1820.—It is not my intention to make any

claim of remuneration for any services that I have performed in the

business referred to. Having been the first inventor of the scheme, and

viewing it as a plan that will ensure great public advantage to the

country, I am sufficiently repaid by the prosperity which it has already

had, and with the prospect of increasing success which the circumstances

of the Society now hold out. I beg, therefore, that you will record an

entire discharge on my part for all the trouble which I have had in the

preliminary part of the institution.

But while I thus disclaim any

pecuniary recompense on my own account, I beg leave to add that the

services of Messrs. Cockburn and Wotherspoon, which were of a more

laborious and professional nature, deserve an ample recompense, and I have

no doubt that their claims will therefore meet with all due consideration.

In recognition of Mr. Wardlaw's valuable services and their disinterested

character the directors ordered that, so soon as there should be a

sufficient balance at the credit of the Expense Fund, a piece of plate of

the value of fifty guineas should be purchased and presented to Mr.

Wardlaw with a suitable inscription.

[The funds of

the Society did not admit of this presentation being made until the first

period of investigation in i8z, when the grant was increased to zoo, and a

massive silver salver was presented to Mr. Wardlaw bearing the following

inscription:

"Presented by THE SCOTTISH WIDOWS' FUND LIFE

ASSURANCE SOCIETY, instituted 1st January 1815, to DAVID WARDLAW of

GOGARMOUNT, with whom the formation of this national institution

originated, and whose valuable services have throughout the past and most

trying years of the Society's progress tended greatly to promote those

gratifying results, which appeared so prominently at the First Periodical

Investigation of its affairs, 1st January 1825."

The "Wardlaw Plate" is

now in possession of the Society, having been purchased at the dispersal

of the effects of Mr. Wardlaw's representative in 1911.

The grants to

Mr. Cockburn and Mr. Wotherspoon's representatives were to bear interest

from 1st January 1815; but, true to the principle so stoutly upheld by Mr.

Cockburn himself, the directors, in approving the report of the committee,

minuted on 10th November 1820, "that the granting of the allowances

mentioned does not affect the stock or general fund of the Society, the

said sums being only exigible from the preliminary Expense Fund when it

will be sufficient to meet these claims, which cannot probably be the case

for a considerable time."

Dr. Andrew Duncan the younger, having been an

extraordinary director from the beginning, had also acted for the Society

during four years and three months in medically examining proposed

insurers. For so doing he received no remuneration from the Society, nor,

it appears, from the persons he examined. It is not surprising, therefore,

that he should write to the Manager as follows:-

14th April 1819.- I may

take this opportunity of stating that, although I am ready and desirous at

all times to assist the Society with my professional knowledge, such as it

is, there might be devised some way of making a remuneration for the

trouble with which it is occasionally attended, and the responsibility

which always accompanies it. I see that some of the London offices have an

office-bearer under the title of Consulting Physician. Whether they have

any salary or emoluments I do not know; but I should be well pleased to be

thus officially connected with yourself and the Society.

In accordance

with this suggestion, Dr. Duncan was appointed consulting physician as

from 3rd May, the fee being afterwards fixed at half a guinea for each

person examined.