|

It is unfortunate that so

little has been written about the Highlands by natives of the country,

who being acquainted with the state of society and manners, would be

able to give an intelligent and unbiassed account of the social

condition of the country in the past, and not left us dependent upon

what has been written by strangers, many of whom were prejudiced, and

who, even though they would have been incline to treat us fairly, could

hardly have done so from their want of knowledge of the language,

customs, and institutions of the people. That there were many

Highlanders even at a remote period who could have done so, there is not

any doubt, for, though there were no schools of learning in the country

previous to the Reformation, many of the Highland youth of good families

got a fair education in Edinburgh and Aberdeen, and some went abroad,

even to France and Italy. Martin, who wrote an account of his tour to

the ‘Western Isles about the end of the seventeenth century, says that

he was not only the first native, but the first who travelled in these

islands, to write a description of them. He makes a complaint which

might very well be repeated at the present day, “That the modern itch

after knowledge of foreign places is so prevalent, that the generality

of mankind bestow little thought or time upon the place of their own

nativity.” and adds, “It is become customary in those of quality to

travel young, into foreign countries, while they are absolute strangers

at home.”

This has left us with

very little knowledge of the social life of the Highland people during a

very interesting part in their history.

During those years

between the Reformation and the “45,” the Highlanders occupied a veiy

prominent part in Scottish History, and it is their misfortune to have

their deeds recorded by historians who showed no disposition to do them

justice. While their bravery and military prowess could not be

denied,—as in disparaging their bravery that of their opponents would be

still further degraded,—the meanest and most mercenary of motives were

attributed to them. The chiefs were represented as being actuated not by

sympathy or principle, but from their inherent love for rapine and

disorder, while their followers were supposed to have no choice in the

matter, but to blindly follow their chiefs without questioning the

object or cause.

We are not so much

concerned in the meantime as to the part the Highlanders took in the

events of those stirring times. Many of the facts are recorded in

history, and their bitterest enemies cannot deny them the credit which

is their due, and we may hope some day to see a History of Scotland that

will do them the justice their conduct deserves. Our purpose at present

is to give so far as we have been able to gather from the limited

sources at our command, an account of the social life in the Highlands

during the last century, and the early part of the present, before the

great changes consequent on the introduction of the sheep-farming system

took place.

Life in the Highlands in

those times was very different indeed from what it is at the present

day.

In a purely pastoral

country like the Highlands, nearly the whole population was necessarily

occupied in one way or another about the land, and everyone must

consequently have more or less land, according to his station, for the

maintenance of his stock, which constituted the wealth of the country.

The land was divided in the first instance in large tacks among the

chieftains or head men, who occupied what was termed “so many peighinnor

penny-lands, and for which they paid a certain tribute annually, partly

in kind and partly in money, in support of the dignity of the chief.

These men again let out portions of the land to the common men of the

tribe, for which they received payment in kind and also in services,

such as cutting and stacking peats, tilling the ground, and securing the

crops, &c.

These services were

rendered according to a regular system, so many days at peat cutting, at

spring work, or harvest, &c. When the services were rendered for land

held direct of the chief, they were termed Morlanachil or Borlanachcl.

When for lands held of the tacksmen, they were termed Cariste. So long

as the patriarchal system prevailed, these services were neither so

severe nor so degrading as they became in later years, when the chiefs

lost all interest in their people. When the strong arms and loyal hearts

of his clansmen formed his only wealth, the chief was very careful of

the comfort of his people, and the tacksman were bound to treat them

justly, as the chief could not depend upon the loyalty of an unhappy

people. When, however, with altered circumstances, after the passing of

the “Hereditary Jurisdiction Act,” they lost the power they formerly

held, of combining together for the purpose of warfare, their love for

their people ceased; farms were let to the highest bidder, and in most

instances, south-country shepherds and stock raisers, took the place of

the Highland gentlemen tacksmen. Then the position of those who were

left as sub-tenants, became uncomfortable in the extreme. The former

tacksmen, from their kindly nature and clannish sympathies, would

naturally treat them kindly, but the new-comers, whose only interest was

the making of money, considered them only as lumber in the way of their

sheep and cattle, and services which formerly were rendered as an

indirect way of maintaining the dignity of their chief, soon became

degrading in their eyes, and very grevious to be borne.

The land held by the

members of the clan under the old system, was divided into townships,

usually leth-pheighinn, or half-penny land to the townships. Penny-lands

were of different sizes, probably according to their value, or custom of

the district.

Skene says, that the

average township in the Mid Highlands consisted of 90 acres within the

head dyke, of which 20 acres were infield, 15 acres were outfield, 10

acres meadow, 35 acres green pasture, and 10 acres woody waste, and the

moorland behind the dyke 250 acres.

The arable land was

usually held on the runrig system, a third of the land being divided by

lot every three years, while each had a stated amount of stock on the

hill pasture. Besides the regular rent charge, each member of the clan

contributed according to his means on great occasions, such as the

marriage of a son or daughter of the chief. These contributions, in the

aggregate, frequently amounted to a good deal. It was customary, even on

the occasion of the marriage of an ordinary clansman, for the neighbours

to make a contribution of useful articles so as to put the young couple

in a good way of house keeping.

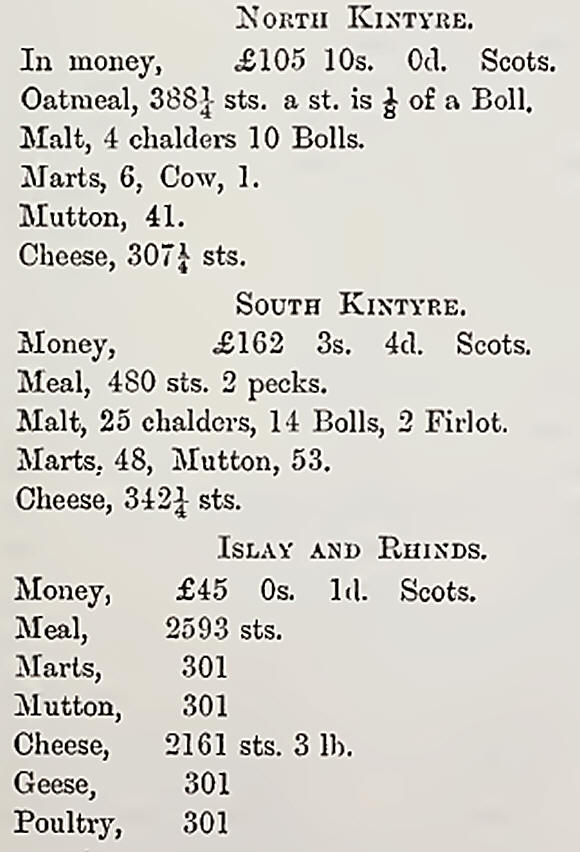

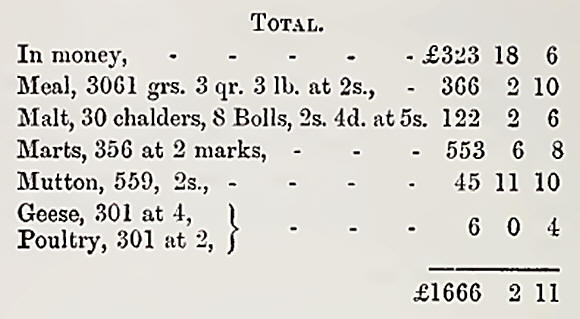

The rent book of a

Highland chief in the olden time would be a very interesting study to

day, with its payments in kind. In the old “Statistical Account’’ of

Scotland, Dr. Smith, of Campbeltown, gives a most interesting statement

of the rental of the district of Kintyre and Islay in 1542, then in the

possession of the Lord of the Isles—

At the time of which we

write there were no slated houses in the Highlands, with the exception

of the castle of the chief and chieftain. The common houses were built

upon the same plan as many of the crofters’ houses of the present day,

with the fire on the middle of the floor. Many of them had the cattle in

the one end of the building, with only a wattle partition plastered with

clay, dividing them from the part occupied by the family. Many more had

barns and stables apart from the dwelling, but were irregularly placed.

From the ruins of hamlets still easily traceable on every hill side, it

can be seen that the habitations of the tenants of former days were

built more substantial, and with more ideas to comfort than the huts of

their successors the crofters.

One cannot, on examining

the ruins of the many castles in the Highlands, but be struck with the

extraordinary strength of the buildings, and it is difficult to imagine

that they could have been the work of the barbarians our ancestors are

supposed to have been, if we believe all we are told by the historians.

In order to give them strength they were built on the ledges of rocks,

or on the most inaccessible promontories, which would make it a very

difficult undertaking, even with all the machinery of the present day.

What it must have been in those days it is difficult to imagine. These

buildings took such a time to put up, and cost so much labour, that it

is not astonishing that the minor gentry contented themselves with

houses of a less pretentious kind.

In foretelling the many

changes that were to come over the country, Coinnecich Odhar, mentions

among other things, that there would be a “Tigh geal air gach cnoc,” a

white house on each hillock, which has been verified in some districts

at least. It is a source of astonishment to strangers visiting the

Western Isles, that the people are content to live in such houses, as

many of them inhabit. From a careful study of the Highland question, I

have become convinced that it is more the misfortune than the

inclination of the people, which causes such an apparent want of desire

to improve their surroundings. I am satisfied that notwithstanding the

insecurity of tenure in the past, they would not content themselves in

such houses were it not the great difficulty of procuring timber, there

being very little growing timber in the islands. This is easily seen, as

in those districts in the Highlands where wood is easily procurable, the

houses are of a superior class, and even in the islands, whenever a

crofter made a little money, his first care was to improve his dwelling,

though frequently at the risk of an increase of rent.

The rearing and dealing

in cattle was by far the most important industry in the country, and

even the principal gentry were engaged in it. They collected all the

cattle, which they bought up usually in the month of September, and

drove them to the Southern markets. The transporting of a drove of

cattle in those days, was a laborious work, as well as a very risky one.

In many cases they had to pay tribute for permission to pass through the

land of a clan with whom the owner did not happen to be on good of

terms. They often ran the risk of encountering some of the Ceathctrnachs,

or broken men who infested the mountain passes on the road, and losing

some of the droves, unless the drovers were strong enough to hold their

own.

In many cases the drovers

did not pay for their herd till their return, and then they went round

their customers, and paid them with scrupulous honesty. Most of them

being gentlemen of honour and position in their respective districts,

the people considered the transaction safe. When occasionally they were

disappointed, the unfortunate thing was that they had no redress—there

was no petitioning for cessio in those days. Rob Donn, the bard, who was

frequently employed as a drover in the interest of his chief, Lord Reay,

and others, composed a very scathing elegy on the death of one of these

characters, who died at Perth, on his way home from the South.

From the want of roads,

cattle was the only commodity that could make its own way to the market,

the small Highland breed of sheep which was reared in the country at

that time, was not usually sent to the Southern markets—this breed of

sheep which is now nearly extinct, with the exception of some few still

reared by the crofters in the Island of Uist, is a hardy little animal,

the wool of which is very fine, and the mutton exceedingly sweet and

tender. I have seen some rams of this breed, with as many as four, or

six horns.

The honourable profession

of “cattle lifting” was not classcd as a common theft—far from it. Many

a Highlander is still proud of his “cattle lifting” ancestors. It was

customary for a young chieftain before being considered capable of

taking part in the affairs of his clan, to make a raid upon some other

clan with whom they were at feud, or into the low country, whence they

considered every man had a right to drive a prey. Some clans obtained a

greater notoriety than others as cattle lifters. The MacFarlans were

such adepts at the work, that the sound of their gathering tune “Togciil

nam bo” was enough to scare the Lowland bodachs of Dumbartonshire. The

MacGregors, again, had a world wide reputation in the profession, while

the MacDonalds of Glencoe and Keppoch, and the Camerons in the Mid

Highlands, were not far behind them in excellence, and my own clan in

the North rejoiced in the flattering patronymic of “Claim Aoidh nan

Creach.” It so happened that those clans who bordered on Lowland

districts, were more given to pay their neighbours those friendly

visitations. In several districts there are corries pointed out where

the cattle used to be hid ; as a rule they are inaccessible, but from

one narrow opening, which could easily be defended against any rescuing

party. It is peculiar that a very high code of honour obtained among

even the most inveterate reivers. A Highland reiver would never stoop to

anything less than a cow from a rich man; the property of the poor was

always safe from them. Private robbery. murder, and petty thefts were

hardly known. It may be said there was nothing to steal, but there was

comparative wealth and poverty as elsewhere, and the poorer the people

were, the stronger the temptation to steal, and the stronger the

principle must have been which enabled them to resist it.

This scrupulous honesty

was not confined to the property of their own kinsfolk, the effects of

strangers who might happen to be among them were equally safe. They were

most scrupulous in paying their debts, and such a thing as granting a

receipt or a bond for money lent, would be considered an insult—Dh

’fhalbh an latha sin!

There was an old custom

of dealing with people who did not pay their debts. The neighbours were

convened and formed into a circle with the debtor in the centre. He was

there compelled to give a public account of his dealings, and if the

judge considered that he had not done fairly, a punishment called “Thin

chruaiclh ” was administered to him. He was caught by two strong men by

the arms and legs, and his back struck three times against a stone.

The instruments of

husbandry in those days were of the rudest description. With the smaller

tenant the greater part of the tillage was done with the ccis-chrom,

same as now used by the crofters in many districts. The plough then in

use was entirely of wood, with perhaps an iron sock, and was drawn by

four, and often by six horses. The horses were yoked abreast, and were

led by a man walking backwards, another man held the plough, and a third

followed with a spade to turn any sods which might not happen to be

turned properly. The whole arrangement was of the most primitive

description, and would look very amusing at the present day.

The harrows had wooden

teeth, and sometimes brushwood in the place of the last row, which

helped to smooth the ground. There being no roads in many districts,

carts could not be used, so that goods had to be carried on horse back,

in two creels, hung upon a wooden saddle with a thick rug made of

twisted rushes neatly woven together. The burden had to be divided, so

as to balance on the animal’s back—if this could not be done it was put

on one side, and stones put to balance it on the other. There was also a

form of sledge used for carrying any heavy article; it was shod with

iron, and dragged after the horses like a harrow; another form had trams

like a cart. The first was called Losgunn, the latter Carn-slaocl. These

are still used in districts where there are no roads.

Such a thing as a gig or

carriage was, of course, out of the question in those clays; indeed,

there are people living, who remember when the first spring conveyance

came to Skye. The remains of this ancient luxury are still to the fore.

It has hail an eventful history, first in the honored services of the

laird, when it carried thereof the island, and was the admired of all

beholders. Then it became the bearer of the laird’s factor; from that it

came down the hill to the service of a tacksman, and finally settled

with a small country innkeeper, where it ended its busy days.

Before the erection of

meal mills, the corn was all ground with the quern, two flat stones

fixed, the one upon the other, the upper having a handle to turn it

round, and a hole in the centre by which the corn was put in; this was

very laborious work. I have seen the quern even yet at work when the

quantity of corn was so small, as not to be worth while sending to the

mill. It is astonishing the quickness with which a smart person could

with this appliance prepare a quantity of meal. A friend of mine on one

occasion had a good example of this. Visiting an old woman in the

heights of Assynt, she was pressed to wait and get something to eat,

whereupon the old matron went out to the barn, took in a sheaf of corn,

and in a minute whipped the oats off with her hand, winnowed it with a

fan at the end of the house, then placed it on the fire in a pot to dry;

after that it was ready to be ground, and then, being put through a

sieve, was ready to bake. The whole thing was done within an hour, from

the time she took in the sheaf of corn, till the cakes were on the

table, and my friend says she “ never tasted better.”

The diet of former days

was very simple, and no doubt accounts for the immunity of our ancestors

from many of the forms of sickness, with which their more degenerate

posterity are troubled. They were at that time, of course, necessarily

restricted to the resources of our own country, which were much better

suited to build up a healthy constitution, than the foreign luxuries of

the present day.

Martin, whom I have

already mentioned, gives the following account of the diet of the people

of Skye, about 200 years ago:—

“The diet generally used

by the natives consists of fresh food, for they seldom taste anything

that is salted, except butter; the generality eat but little flesh, and

only persons of distinction eat it every day and make three meals. All

the rest eat only two, and they eat more boiled than roasted. Their

ordinary diet is butter, cheese, milk, potatoes, colworts, brochan i.e.,

oatmeal boiled with water. The latter, taken with some bread, is the

constant food of several thousands of both sexes in this and other

islands during the winter and spring, yet they undergo many fatigues

both by sea and land, and are very healthful. This verifies what the

poet saith—Popvlis sat est Lymphaque Ceresque: Nature is satisfied with

bread and water.”

As far back as the year

1744, in order to discourage the use of foreign luxuries, at a meeting

of the Skye Chiefs, Sir Alexander MacDonald of MacDonald, Norman MacLeod

of MacLeod, John MacKinnon of MacKinnon, and Malcolm MacLeod of Raasay,

held in Portree, it was agreed to discontinue and diseountenance the use

of brandy, tobacco, and tea.

Though they could not be

said to be addicted to drink, the Highlanders of that period used a

considerable quantity of liquor, but more as a daily beverage than in

drams, as at the present day. Martin relates some curious drinking

customs. When a party retired to any house to transact business and had

a refreshment, it was usual to place a wand across the doorway, and it

would be considered the utmost rudeness for anyone to intrude, while it

remained there.

Ale formed a great part

of the beverages of those days, and houses for the sale of ale were

numerous, even in Tiree. It was not till the latter end of last century

that whisky was sold in these houses.

Drinking at marriages and

funerals was frequently carried to excess, particularly the latter. At

marriages the dancing and other amusements helped to evaporate some of

the exuberance, but at funerals, they drank to keep down their grief,

and as they had often to carry the bier a long distance, they took

frequent refreshments by the way, and more after the burial, with the

result that very unseemly conduct often took place. The Highlanders are

not more blameworthy in this respect than others, for the same was

practised in all parts of Scotland at that period. These barbarous

customs are happily gone, which we have no reason to regret.

The marriage feasts were

great affairs. They lasted usually for four days—dancing, feasting, and

singing songs, being kept up the whole time. The dancing usually took

place in a barn, which in some districts, was a building of considerable

dimensions, and the friends coming from a distance, for whom room could

not be found in the house, were put to sleep in outhouses on

shake-downs, or billeted in the neighbouring houses.

It was on the occasion of

a wedding of this description, that Rob Dunn composed the well known

song, “Briogais Mhic Ruairiilh.”

In the olden times the

pipe and the song were frequently heard in every Highland clachan, and

the youths of the country could enjoy themselves in a rational manner.

Shinty, putting the stone, tossing the caber, and other manly exercises,

were freely engaged in, the different districts and parishes vying with

each other in friendly rivalry, but the Calvanistic doctrines of the

Highland clergy preached all the manliness out of the people, and I

don’t think that even they will be bold enough to assert that they have

preached anything better into them.

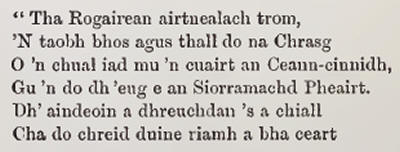

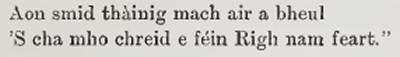

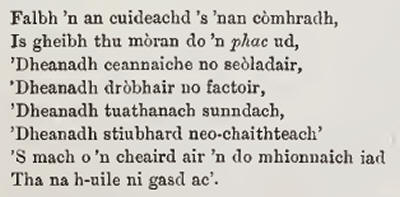

As Rob Donn so very

graphically says of them—

Join their clubs and

society

You’ll find most of the pack of them

Fit for pedlars and sailor?,

Fit for drovers or factors,

Fit for active shrewd farmers,

Fit for stewards, not wasteful,

Their sworn calling excepted,

Fit for everything excellent.

It is wonderful after all

how tenacious our old mother tongue has been of its life. It seems the

insane policy of denaturalizing the Highlanders, in order to civilize

them, has not been an idea of modern years. As far back as 1795, an Act

of Parliament was passed beginning thus—<l Our Sovereign Lord,

considering that several of the inhabitants of the Highlands are very

refractory in paying to the chamberlains and factors, the rents of the

Bishopric of Argyle and the Isles, which now His Majesty has. been

graciously pleased to bestow upon erecting of English Schools for the

rooting out of the Irish Language (Gaelic) and other uses.”

Strange that after two

hundred years of this denaturalizing process, the Gaelic language is

spoken by more people now than it was then, and looks quite robust

enough to stand two hundred years yet.

As might be expected from

the rude implements of husbandry in use, the ignorance of the best modes

of agriculture, as well as the want of roads and communication with the

southern markets, there were occasionally seasons of severity owing to

bad harvests, and in such times, the poor people were reduced to sore

straits, and were it not for the kindly feeling which existed among the

different classes of society, serious consequences might have happened,

but in those times those that had, shared with those who had not.

In seasons of severity,

many had recourse to a very barbarous means of increasing their store of

provisions, by bleeding the cattle and mixing the blood with meal, which

was said to make a very nourishing diet.

Besides the usual butter

and cheese, they made many preparations of milk, such as “crowdy ”—that

is, the curdled milk well pressed, and cured with a little salt and

butter. “Onaich” or frothed whey. This was done with a stick having a

cross on the end, over which was placed a cord made of the hair of a

cow’s tail. This instrument was worked round in the whey swiftly between

the two hands, which quickly worked it into a thick froth.

Another more simple

preparation was the. “Stajjag,” made of cream, with a little oatmeal

stirred into it. After the introduction of the potato, there was no

famine in the Highlands till the unfortunate failure of that crop in the

year 1846-7, and owing to the changes which had taken place by divorcing

the people from the soil; that famine is counted the severest that is

known to have visited the country. Of course, it must be understood that

the Highlands was not the only part of the country that had these

periodic visitations of famine; such were quite common in these times in

the most fertile districts of England, before the principles of

agriculture were so well understood. It is, however, melancholy to

reflect that while other districts of the country have been making great

strides forward in social progress, and that while in every other place

“two blades of grass grow where only one grew before,” in the Highlands,

the reverse is the case. Where corn and barley waved a hundred years

ago, heather and rushes grow luxuriantly to-day —a sad comment on our

civilization and progress !

For a picture of the

Social State of the Country about the end of last century, the following

extract from the old “Statistical Account of Scotland,” 1792, referring

to the parish of Assynt, by the Rev. William Mackenzie, minister of the

parish, is perhaps the best estimate we could have of the condition of

the Highlands at that period—“Properly speaking, though many here are

poor, they cannot be represented as a burden on the parish. The natives

are all connected by alliance. When any one becomes old and feeble, the

nearest relations build a little comfortable house close to their own

residence; and even there the distaff and spindle are well managed.

These old matrons nurse the children of their relations; the songs and

airs of Fingal and ancient heroes are sung in the Gaelic tongue, to

which the little children dance. Old men are prudently engaged in

domestic affairs, such as repairing the houses of the neighbours, &c. In

short, they share with their relatives all the viands of the family. At

this period the poorest stranger, even though he be unacquainted, finds

charity and safe shelter; but there is a very great distance (and now no

places as of old) in this wilderness betwixt this parish and the inn at

Brae of Strath o’ Kill. Such being the condition of the poor in Assynt

Parish, there are no public funds. The little trifle of money that is

collected every Sabbath day after divine worship is served, is yearly

distributed amongst the most friendless and deserving poor.”

SECOND PAPER

He knows but little, I

think, of Highland history who does not admit and deplore the absence in

our day of some of those splendid elements of character, the kindly

feelings of mutual confidence that bound the people to each other and

all to their chiefs, the conditions of life and surroundings under which

the people lived, so favourable as these were to the strengthening of

those ties and the development of those traits of character for which

our ancestors were distinguished. Contrast those times with the present,

and look upon the almost distracted condition of the

Highlands—agricultural and almost every other industry on the verge of

ruin ; and instead of the old feelings of mutual confidence and

attachment to their chiefs, you have almost everywhere a discontented

people, in some districts at open variance with their proprietors, the

natural successors of those to whom in a former age they were so firmly

attached. Look at the wilderness aspect of those straths and glens,

which even in times and under circumstances less favourable to

agriculture and stock-rearing in the Highlands, supported thriving

contented communities. Look at the uncomfortable condition of the

landless masses, who either struggle on patches of unsuitable soil or

form the unproductive populations of the towns and sea-coast villages ;

and I think it must be admitted that whatever difference of opinion may

exist as to the causes and remedies, there can be no difference of

opinion as to the fact that the social condition of the Highlands is not

satisfactory, and contrasts unfavourably with the past, in days not long

gone by.

It is sometimes said that

the mere rehearsal of grievances and wrongs, which, to say the least,

originated in a past age, and for which a past and departed generation

is mainly responsible, is neither fair nor of much practical effect

towards having those grievances remedied. To this it may be replied that

could there now be traced on the part of the Highland landowners, or

that section of the public press which supports their past policy,

symptoms of a generous acknowledgment of those wrongs, and a desire to

trace the present agitated state of the Highlands to something like the

natural causes, then, I say, we might be expected to (and readily would)

draw a veil over much of what is regretable and even discreditable in

the past treatment of the Highlanders. We might then be asked from

henceforth to say nothing more about the clearing of the straths and

glens, or that purely commercial policy which, to make room for sheep

and deer, drove the best of the people into exile, or to the morally as

well as physically unhealthy atmosphere of the towns.

Where, however, in all

the public utterances of landlords and that section of the press just

referred to, do we find a trace of such an acknowledgment On the

contrary, is not the present unfortunate social condition of the

Highlands attempted to be traced to almost every cause and influence

except those which will by-and-bye be found the real ones

In illustration of this,

perhaps I may be allowed to refer to that excellent and sympathetic

address recently delivered to this Society by our late chief, Lochiel.

It may be taken as representing the views of the best and most

sympathetic among our Highland lairds. In the efforts that must soon be

made to heal the breach that apparently in the Highlands is widening

between the owners and occupiers of the soil, Lochiel’s expressed

opinions must always deservedly exert a most important influence. In

dealing, in that address, with the present agitation in the Highlands,

he, however, as I humbly think, falls into two common errors. He

under-estimates its importance and traces its origin to circumstances

and incidents by far too recent and local in their character. He says—

“The history of the

agitation in the North is short. It began not a very long time ago. It

was insinuated by the quasi famine, owing to the bad harvest of 1882,

and was brought into more prominence by debates in the House of Commons,

and it finally received more notoriety by the appointment of the Royal

Com mission.”

This short and ready

explanation of the present condition of the Highlands is not

satisfactory to many who have given the subject some earnest impartial

attention. Many—and their number is increasing—believe that the present

agitation originated not two years or twenty years ago, but that it

originated many years ago along with, or rather out of, that policy of

the depopulation of the rural districts which so much altered and

disturbed the social life of the Highlands. Every small holding

extinguished so as to increase the size of the big sheep farm, every

acre of ground thrown out of cultivation to increase the dimensions of

deer forests —these, and not a recent bad harvest, were the incidents

that helped to develop it; and what more than the appointment of the

Royal Commissioners gave this agitation its recent activity and

notoriety, is the development of Mr Winans’ deer forest, which, not

content by the swallowing of thousands of acres of good laud stretching

from the East to the West Coast of Scotland, threatens to clear off the

land of their ancestors the entire community of crofters and cottars,

not even tolerating the bleat of Murdo Macrae’s pet lamb on the fringe

of tins huge forest. These matters surely had, and have, something to do

with the present condition of the North; and yet in Lochiel’s excellent

speech they found not a single reference.

There is, however,

another class of speakers and writers who, when dealing with the present

state of the Highlands, not only ignore the primary causes of the

present trouble, but assume a tone and give expression to sentiments

that certainly are not calculated to soothe the irritations that

unhappily exist. I refer to those who profess to see in this movement an

agitation originated and fostered by external influences only. By such

critics those who venture to condemn the depopulating of the past, or

demand the redress of present grievances, are branded as outside

agitators, actuated by selfish and unworthy motives. Now, although the

history of this movement warranted this tone and these insinuations in a

greater measure than it does, I think it is an exceedingly ill-advised

method of dealing with such a social agitation, especially among

Highlanders. To attempt to suppress a constitutional agitation for the

remedy of recognised and well-defined grievances by mere bullying ; to

drag the names of respectable and loyal citizens who express sympathy

with the people through the press in columns of sarcasm and ridicule, is

as foolish as it is unfair. Such treatment has a two-fold pernicious

effect on this or any similar movement; it deprives the agitation of the

advice and influence of many who, while quite in sympathy, are too

sensitive to face the sneers and sarcasms to which connection with such

a movement exposes them. But this is not all, for just in proportion as

the more sensitive (not unfrequently the more real) people are

alienated, in the same ratio does the control and guidance of the

agitation fall into the hands of those whose personal feelings are not

so sensitive, and who on that very account will, in the final

adjustment, show less regard to the feelings and interests of the other

party in the conflict.

I do not know that there

are many lessons that the modern history of Europe teaches more forcibly

than this, or an error more frequently repeated in dealing with

agitations for the redress of social and political wrongs.

After references to the

case of France and of Ireland, the speaker proceeded :—

It is to be hoped,

indeed, from the past history and character of the Highland people, we

may say it is absolutely certain, that this Highland movement will never

show any trace of similarity to that of France or Ireland. At the same

time, I hesitate not to say that should this agitation in the future

develop a more objectionable tendency, the responsibility will rest on

the apathy of those who are now appealed to for reasonable remedies. To

any one who has given the least attention to the past history of the

Highlands, the theory that the present agitation and the unfortunate

relationships existing in some places between proprietors and people is

the mere outcome of outside influences and agitators, is as unlikely as

it is absurd.

The present agitation

would never have originated, far less assumed its present importance,

did there not exist in the conditions and surroundings of the people

abundance of that material on which such agitations flourish. The

feelings and sentiments of a people, especially the Highland people,

towards their superiors and landlords could never have undergone such a

manifest change at the bidding of any outsider, however influential, or

under the promise of rewards, however tempting. A little less than a

century and a half ago the powerful influence and threats of the English

Government was brought to bear on the Highlanders to induce or compel

them to turn their backs on their chiefs and the cause they supported.

What a strange contrast does the conduct of the people of that time

present to the present. Then neither the threats, the promises, nor the

dazzling reward of £30,000 offered by the Government, would induce the

men and women of Skye to forsake their chiefs or the prince whom they

believed to be their sovereign. Now the scene is changed, and the

Central Government has to send the military to Skye to enforce those

obligations which, in a former age, no pressure or reward would induce

the people to violate. Such a change as this indicates in the temper and

relationship of proprietor and people affords surely food for

reflection, not only to the proprietors, but to the nation as well. When

troubles surround our wide-spread interests abroad, and when even still

more alarming dangers manifest themselves in our large towns at home, it

is surely not a time to alienate the affections of a people always the

most loyal and law-abiding—a people who have more than once proved the

country’s protection in the hour of need.

In the face of the abuse

heaped on those who now venture to sympathise with the present

grievances, and condemn the policy which has so depopulated the rural

districts in the Highlands, it may not be out of place to notice that,

if they err, it is in the company of many with whom it is no small

honour to have any association whatever.

That the Highland people

have got but scant justice has been quite as earnestly expressed in the

past as it is in the present day; and that by men and women with whom,

in point of culture, patriotism, and sound sense, the modern critics

will bear no comparison. Nearly a century ago, and just when in the new

departure in the Highlands sheep and deer were replacing men, that lady

of culture, Mrs Grant of Laggan, in some of those splendid “ Letters

from the Mountains,” took occasion to denounce the clearances, and

express her sympathy with the people. General Stewart of Garth, who

thoroughly appreciated the character of the Highlanders and their

military value to the nation, reiterated the same opinions. Hugh Miller,

whose deep philosophical mind and scientific mode of thinking and

writing would surely place him above suspicion as a mere agitator, saw

the wrongs inflicted on the people, and denounced them in the severest

language. The Macleods of Morven wept and sung melancholy dirges over

the desolations that surrounded their once populous parishes. And what

shall I say of that brave and gallant youth who, to the grief of his

countrymen, recently lost his life in that struggle that has now cast

such a halo of melancholy interest over the Soudan. In John A. Cameron,

of the Standard, the Highlanders lost their latest and best friend. His

life, short as it has been, was far too real to allow vague theories and

sentiments have for him any attraction, and yet his chivalrous nature

responded to some of the grievances of his native Highlands. During the

earlier troubles in Skye his stirring letters to the Standard newspaper

gave the social condition of the North an interest to the higher circles

of English society that it never had before, and from the publicity thus

obtained good will follow. Some of his latest literary work before

leaving for the Nile were, I think, papers in some of the magazines

bearing on Highland subjects. In one of these he drew public attention

to the degenerating composition of the Highland regiments, deploring

that some of these were fast becoming Highland in name only, by the

necessity of filling the ranks from the large towns. Another, a paper

entitled “Storm Clouds in the Highlands,” is full of melancholy

interest, giving ample promise that had he lived the best interests of

his native Highlands would have in him an earnest advocate. If it were

really necessary to say more to vindicate the justice of the claims made

on behalf of the Highlands by referring at greater length to the

character of those who in the past as well as the present recognised and

advocated those claims, I might furnish you with a list long enough of

Scotchmen and Englishmen whose very names and association with this

movement should protect it from the harsh criticism we are so accustomed

to hear. When the critics and newspapers who ridicule the efforts of

those who in the present day advocate land law reform in the Highlands

shall be forgotten, a future age will set its proper value on the

services rendered by such men as Professor Blackie, Mackay of Hereford,

and the ever-increasing band who are at present fighting the people’s

battle. I would not refer to this matter so much for the mere object of

indicating the character and motives of the Highlanders and their public

friends, even if this were necessary, as it is not, but I avail myself

of this opportunity of protesting against harsh and unfair insinuations

on public grounds, and in the interest of law and order throughout the

Highlands, and as such criticism has a tendency to irritate and rouse

feelings once awakened not so easily calmed down.

It is hardly necessary

for me here to say that the greatest obstacle in the way of social

reform in the Highlands at present is the conduct of those of the people

who, in their efforts to obtain redress, do not strictly adhere to

constitutional and peaceable means, and who, while able to do so, refuse

to discharge obligations which honour and morality demand. Highlanders

should at this time in particular remember that every act of

lawlessness, as well as every unreasonable demand, throws discredit on

their movement, and frustrates the best efforts of their friends.

Let me now assume that

what I have so far been pointing out is to a certain extent at least

correct; let me take for granted that you admit that there are in the

circumstances and surroundings of the people grievances that call for

remedies; let the characters and motives of those who advocate those

remedies be at least respected; let landlords and factors, county

officials, and a section of the press, for a time at least, sheathe

those weapons of cold indifference and active irritation which have

hitherto marked their attitude towards this movement; and then, and not

till then, I venture to say a foundation lias been obtained on which

good will and mutual co-operation may yet build a future of peace and

prosperity for the Highlands.

I say mutual

co-operation, for if the present condition of the Highlands is to be

improved, three parties must co-operate, each fulfilling their

respective obligations—the Legislature, the proprietors, and the people.

Speaking generally, this combined action must tend in the immediate

direction of gradually reversing the policy which has for so long

influenced land legislation, estate management, and the system of

agriculture in the North.

The unnatural exodus of

the people from the rural districts into the large towns and villages

must be stopped : not by any arbitrary or artificial means, but by

creating in the rural districts conditions of life and surroundings more

attractive than at present exist. This process of clearing the people

from the rural districts, and the natural effect of rapidly increasing

the population of the towns, is unhealthy and dangerous. The whole

tendency of the present land laws and systems of estate management

encourages this process. What of the land that is not idle and

unproductive is year by year passing into fewer hands ; there is thus

less labour needed and less food produced. A first step in the right

direction would, I think, be the immediate alteration of those laws of

entail and primogeniture that at present bind up so much land in the

nominal hands of those who have neither the power or the means to

develop its resources. A veto must at the same time be put on the

further increase of deer forests, or such other arrangements as

withdraws the land from its proper use, and limits the quantity.

Without the active

interference of the Legislature, I think that from the present state of

agriculture in this country, and the evident collapse of the past system

of large farms, the good practical sense of the proprietors will

encourage an immediate increase in the number and size of small

holdings. Legislation must, however, give the tenant a tangible security

of tenure, and an undoubted claim to whatever improvements he makes or

additional value he adds to his holding, with a perfect right to dispose

of his interest in the same to the best advantage. In connection with

this, it is often said that security of tenure with or without leases

already exists on most estates in the Highlands. In reply to this, it

need only be said that that security of tenure a man holds dependent on

the goodwill of his proprietor or the customs of the estate, is by far

too unsatisfactory aud precarious, compared with that security

established by law. A change of proprietorship, a mere dispute with one

of the estate officials, may disturb the former, while the latter is

dependent only on his proper performance of his lawful obligations, and

is much more conducive to independence and a greater incentive to

industry. Placed in a satisfactory position in his tenure and in his

rights to his improvements, I do not know that it would be desirable to

fix rents by legal processes such as the proposed land courts. This, I

fear, would tend to create new difficulties, and lead to frequent and

expensive litigation, adding to the objectionable extent to which our

social and business arrangements are already in lawyers’ hands. An

agricultural holding, like other places of business, must always be more

or less affected by other circumstances than the position and nature of

the soil, such as the amount of industry and intelligence brought to

bear upon it; and no land court, however impartial, can on the whole so

surely and safely determine the value of such holdings as the healthy

action of the natural law of supply and demand.

Here, however, we are at

once confronted with the great difficulty in the Highlands, the limited

quantity of land available for the multiplication of small holdings. At

present the tenant looking out for such is placed at an enormous

disadvantage ; he has to make terms for a commodity the value of which

is naturally increased, and the supply of which is restricted by the

long operation of unhealthy influences. This, however, is surely a

difficulty that the wisdom of Parliament and the proprietors ought to be

competent to deal with. The unprofitable history of large farms for the

past few years, and the greater success attending the smaller holdings,

clearly indicate that even in the interest of the rent-roll the increase

in the number of the latter is advisable. The alternative of deer

foresting large farms falling vacant, so much acted on of late, is one

not in favour with popular opinion—in fact, it is not only in the rural

districts but in the large towns becoming regarded as a social evil,

limiting the food-producing capacity of the country. Any one who studies

the signs of the times can see that “ the coming democracy” has its eye

on this and similar alienation of land, and if these matters once become

the subjects of practical legislation, we may depend upon it that the

reforms effected will be much more drastic than the reasonable

concessions that are now demanded.

But let me now suppose

that the difficulty of the present limited area of land available for

small holdings be got over by the voluntary breaking up of the large

farms and the compulsory curtailment of deer forests, we are again

confronted with the next difficulty, the want of means on the part of

the great body of the people to stock such holdings. Now, every one

admits that in the present condition of the Highlands this is a

difficulty, but I cannot help thinking that it is a difficulty to some

extent exaggerated, and a difficulty very much occasioned by the policy

of the past, for which the people are less responsible than is usually

admitted. On this account, the inability of the people to stock the land

ought to be referred to in a more kindly and considerate manner than is

sometimes done. If many of our Highland people have not the means to

stock the land with, we must not forget that they once had means, and

stock too, but in many instances by the sudden evictions from their

holdings, they were compelled to part with stock at little value, and

the want of subsequent employment soon dissipated the little means that

the expenses of removal left.

In their present

condition, however, the difficulty of want of capital is surely not

insurmountable. Once let the Highland crofter have security in his

tenure, and a legal right to whatever increase of value he gives his

holding in the form of stocks or other improvements, and I am bound to

say that the necessary aid will be forthcoming when required.

To the merchant, the

banker, and capitalist there is no safer investment than the

requirements of the holders of moderately sized holdings on such secure

footing as 1 have indicated. The scale of their operations does not

expose them to the risks and expenses attending a more extensive system.

The circumstances are better known to themselves and more readily

ascertained by those who have dealings with them. Money invested on the

security of industrious Highland small farmers and crofters, and thus

employed in developing the resources of the Highlands, is surely as safe

and well employed as in those foreign securities that have within recent

years swallowed up so much of even Highland capital. I am told on

reliable authority that within a few years back considerably over a

quarter of a million of money has been lost to Inverness and

neighbourhood in investments of this class—surely a strong argument for

seeking safer and more creditable investments at home.

For the investment of

such capital, the Highlands at this moment offer a wide, profitable, and

patriotic field. The food-producing powers of this couutry are being

neglected, so that year by year we are becoming more and more

dangerously dependent on foreign supplies. Not only in the towns, but in

country villages and rural districts, the people almost live entirely on

foreign food, and not only those commodities for the production of which

our soil and climate are unsuitable, but those articles which could be

grown and produced in this country better than in almost any other.

Every shilling’s worth of such food imported is so much added to the

wealth of the nation we buy from, and is equally so much reduction in

the wealth of our own. With, I suppose, about 35,000,000 of people in

this country to provide food for, the British agriculturist has a wide

field for the sale of his produce. If, as I have said before, we make a

large allowance for such articles for the production of which our

climate and circumstances may not be suitable, and in the position to

compete with the foreign farmer, there is still a wide field in other

articles in the production of which the British farmer, and particularly

the Highland crofter, might profitably compete.

In a magazine the other

day I came across some statistics of foreign food importations that in

the present condition of this country generally, and in the Highlands

particularly, were almost staggering. This writer, quoting reliable

Board of Trade statistics, says that we import annually, apart from

wheat and other kinds of grain, over £38,000,000 in articles that could

easily and profitably be produced at home. I shall only mention a few of

these, and in round numbers :—

Pork, cured and fresh ...

... ... £8,000,000

Butter ... ... ... ... ... 11,400,000

Cheese ... ... ... ... ... 4,700,000

Eggs ............... 2,400,000

Lard ............... 1,800,000

Onions ... ... ... ... ... 1,000,000

Potatoes ... ... ... ... ... 130,000

And ten other articles of

a similar class. Now, if we have in this country, and in the Highlands

particularly, the two great factors in food production, the land and the

people, is it too much to say that if not in the interests of the people

themselves, then in the wider interests of the nation, these two should

be brought together.

We must not forget,

however, that other remedies are proposed for the improvement of the

social condition of the Highlands, and to one of these in particular I

wish to draw your special attention. It is, you are aware, proposed that

it would be better for us to buy our food from abroad than produce it at

home, and the people are asked to improve their condition by emigrating

to other lands. I shall not take up your time at present by refer-ing to

the fallacy of the former remedy, but I have a word to say as to the

latter. I am not going to disparage emigration as a powerful and often

successful means in improving the condition of the people ; and when

carried out under such favourable circumstances and generosity of spirit

as seem to be the case on the estates of Lady Gordon Cathcart, I think

such a remedy is deserving of praise. I confess, however, that I look

with grave suspicion on many of the emigratory proposals now made to the

Highlands. We have seen over and over throughout the Highlands that

emigration, on however large a scale from a given district, does not

improve the condition of those who are left, as the land thus vacated is

not appropriated to them. In cases like these, emigration, as a remedy,

is only a mockery. Districts might be named where the present population

is only a percentage of what it once was ; and yet the condition of the

remnant left is worse than in the days of alleged congestion. This

indiscriminate emigration from the Highlands may be one of the causes of

the present poverty. From an industrial point of view the best portion

of the population are driven away—the young, the active, and the more

intelligent —leaving behind those less able to do for themselves. The

former, to become our keenest competitors in the productive industries

of other lands ; while the latter become year by year the unproductive

classes at home. Looking at the matter broadly, and in the light of much

of what has come under my own observation, I am not sure that the

glowing prospects of the successful career of the Highland emigrant is

too often realised, at least in the measure expected. Of course there

are many instances of emigrants getting on well in the land of their

adoption; but, at the same time, I suspect that there are many cases of

emigrants suffering privations, hardships, and ultimate failure,

intensified by the absence of the soothing influences of home and

kindred; and I suspect that the history of Highland emigration furnishes

as many sad tales of this sort as throws a shade of gloom over the

bright side of the picture. Last year a remarkable instance of the

uncertainties and hardships attending emigration came under our notice

here. I understand that the facts are still under investigation, and may

yet attract some attention. Shortly after the troubles that made the “

Braes ” famous, a body of Skye people (including some of those who were

conspicuous in that trial) were induced to emigrate to North Carolina.

According to the apparently-truthful story of two of the men who came

back to collect as much as would bring home their families, their fares

to the port of shipping, as well as their passage to North Carolina,

were paid, they knew not by whom. The prospect of plenty work and good

wages was held out to them on arrival, with other brighter prospects for

the future. On their arrival, however, they discovered to their bitter

disappointment that both promises and prospects were a delusion. Where

work was obtained, the only wages given was the bare food, and the

houses provided were the small one-roomed huts (as one of the men

remarked) once occupied by slaves. The 70 emigrants, scattered over the

country at long distances from each other, struggled on in the hope of

better treatment so long as the means they brought with them lasted.

Their condition, however, getting worse instead of better, and the food

and the climate telling injuriously on their health, those who could do

so left the place. The poor men who told this story in Inverness and

other places had no means left to bring back their families. By the kind

assistance of some friends and countrymen they have, I trust, by this

time been enabled to rescue the remaining members of their families from

the desperate condition into which they consider themselves to have been

misled. The melancholy tale of the hardships and disappointment

experienced by this small band of Skye emigrants is, I suspect, if all

were known, not unfrequent in the history of emigration from the

Highlands. The sufferings experienced by the earlier emigrants to the

North American colonies are matters of history, and when one ponders

over such records as these, one is forced to ask the question, is

emigration really the only alternative 1 Can no other means be found to

relieve the congestion of population in certain districts in the

Highlands by presenting opportunities for migration to other districts

where the presence of an industrious people would be a mutual benefit to

themselves and the proprietor. What has already been done in this

direction gives ample encouragement to do more. Let me give you one

instance. Between 30 and 40 years ago a large number of the inhabitants

of a Highland glen I know of had to leave owing to the new estate

arrangements of large farms characteristic of those times. I suppose

that the large majority of those people shared the common fate usually

attending such changes, either emigrating or finding shelter in the

Lowlands. By what seems to have been a chance more than anything else,

however, some IS or 20 families got a settlement on a piece of not very

promising land on the southern side of Knockfarrel, in the neighbourhood

of Strathpeffer. Here those families and their descendants formed what I

consider a model Highland township. Generously treated as they have been

by their noble proprietrix, even in the absence of much early

agricultural training, they have, by sheer hard work and industry,

converted that patch of comparative moorland into one of the best

cultivated and attractive clusters of small holdings to be found in the

Highlands. The area of land under cultivation does not, I think, much

exceed 150 acres ; yet on this limited area has existed for so long

almost as large a population as is to be found (holding land at least)

in the extensive glen from which they migrated. Perhaps you will allow

me to quote the complimentary reference made to this community by their

factor, Mr Gunn, Strathpeffer, in his evidence before the Royal

Commission :—“It happened that a colony of crofters who were removed

from another estate, to the number of eighteen families, applied for

this new land, and the Duchess of Sutherland, then Marchioness of

Stafford, yielded to their importunities and gave them possession,

granting them leases and materials with which to biiild houses. It is

due to these people to say that, with scarcely one exception, they have

proved to be excellent tenants in every respect. They are industrious,

and farm systematically and well, and of this we have the best evidence

in the fact that they pay their rents regularly, and that within the

last few years most of them have substantially improved their houses,

four of which have lately been slated.” To this testimony it may be

added, without fear of contradiction, that in their characters, social

arrangements, and the discharge of all outside obligations, this little

township is a credit to themselves and to the Highlands. Living

compactly together, and having common experiences, they have retained

among them many of those kindly feelings and mutual interest in each

other so characteristic of the Highland people of the past. The old

people among them, now almost passed away, were with few exceptions

carried back to their native glen, wishing with true Highland instinct

to mix their dust with those of their kindred. I have just referred to

this case to show that if such comparative success has attended

migration of an almost accidental character, what could, and may still,

be done under systematic efforts and greater encouragements. This

continual cry about the glories of emigration, with its glowing

prospects of wealth and fortunes, and entirely ignoring the

possibilities of industrious welldoing at home, has a demoralising

effect on the minds of the rising youth of the Highlands. Between the

squalid misery so often pictured to us on the estates of Skye, and the

ideal wealth of the emigrant, there is a wide field still unoccupied at

home, however much that field may be despised by the false teachings of

modern political economy. The maximum of happiness is not always found

in the effort to amass a fortune any more than in extricating oneself

from the toils and privations of poverty; possibly it is more to be

found in the medium condition of constant industry reasonably rewarded.

A complete reversal of the present agricultural system in the Highlands

would bring the people nearer this condition than anything else I can

think of. In agricultural and rural occupations perhaps, oftener than in

any other, is realised the ideal life of the poet—

“Toiling, rejoicing,

sorrowing,

Onward through life he goes,

Each morning sees some task begun,

Each evening sees it close :

Something attempted, something done,

Has earned a night’s repose.”

And as another of our own

poets has beautifully expressed it, there may be more real pleasure and

profit in constant industry than in the accumulation of wealth—

“’Tis the battle, not the

prize,

That fills the hero’s heart with joy,

And industry that bliss supplies

Which mere possession might destroy.”

When legislation will

give the Highland people a firmer footing on the land, and place more of

it at their disposal; when the present agitation ceases, because its

objects shall have been gained ; then will arrive a testing time in the

history of the Highlands as trying as any through which they have yet

passed. If the people are to preserve not only their own reputations,

but that of their ancestors, they will face the new and improved

condition in a manner that will command respect. When present grievances

are remedied there should be no desire to create new or imaginary ones,

and there should be an earnest effort made to revive those feelings of

goodwill and confidence—feelings between proprietors and people so

happily expressed in the good old motto:—“Claim nan Gaidhcal an

guaillibh a elieile.” Then shall our western isles, our straths and

glens, romantic in scenery as well as in history, become once again the

home of a people who, while they brook no injustice, will readily

acknowledge with gratitude such improvements in their social condition

as wise legislation and the prudence of the proprietors may bring about. |